User login

Child murder by parents: Toward prevention

Deaths of children who are killed by their parents often make the news. Cases of maternal infanticide may be particularly shocking, since women are expected to be selfless nurturers. Yet when a child is murdered, the most common perpetrator is their parent, and mothers and fathers kill at similar rates.1

As psychiatrists, we may see these cases in the news and worry about the risks of our own patients killing their children. In approximately 500 cases annually, an American parent is arrested for the homicide of their child.2 This is not even the entire story, since a large percentage of such cases end in suicide—and no arrest. This article reviews the reasons parents kill their children, and considers common characteristics of these parents, dispelling some myths, before discussing the importance of prevention efforts.

Types of child murder by parents

Child murder by parents is termed filicide. Infanticide has various meanings but often refers to the murder of a child younger than age 1. Approximately 2 dozen nations (but not the United States) have Infanticide Acts that decrease the penalty for mothers who kill their young child.3 Neonaticide refers to murder of the infant at birth or in the first day of life.4

Epidemiology and common characteristics

Approximately 15%—or 1 in 7 murders with an arrest—is a filicide.2 The younger the child, the greater the risk, but older children are killed as well.2 Internationally, fathers and mothers are found to kill at similar rates. For other types of homicide, offenders are overwhelmingly male. This makes child murder by parents the singular type of murder in which women and men perpetrate in equal numbers. Fathers are more likely than mothers to also commit suicide after they kill their children.5 The “Cinderella effect” refers to the elevated risk of a stepchild being killed compared to the risk for a biological child.6

In the general international population, mothers who commit filicide tend to have multiple stressors and limited resources. They may be socially isolated and may be victims themselves as well as potentially experiencing substance abuse.1 Some mothers view the child they killed as abnormal.

Less research has been conducted about fathers who kill. Fathers are more likely to also commit partner homicide.5,7 They are more likely to complete filicide-suicide and use firearms or other violent means.5,7-9 Fathers may have a history of violence, substance abuse, and/or mental illness.7

Neonaticide

Mothers are the most common perpetrator of neonaticide.4 It is unusual for a father to be involved in a neonaticide, or for the father and mother to perpetrate the act together. Rates of neonaticide are considered underestimates because of the number of hidden pregnancies, hidden corpses, and the difficulty that forensic pathologists may have in determining whether a baby was born alive or dead.

Continue to: Perpetrators of neonaticide...

Perpetrators of neonaticide tend to be single, relatively young women acting alone. They often live with their parents and are fearful of the repercussions of being pregnant. Pregnancies are often hidden, with no prenatal care. This includes both denial and concealment of pregnancy.4 Perpetrators of neonaticide commonly lack a premorbid serious mental illness, though after the homicide they may develop anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or adjustment disorder.4 (Individuals who unwittingly find a murdered baby’s corpse may also be at risk of PTSD.)

Hidden pregnancies may be due to concealment or denial of pregnancy.10,11 Concealment of pregnancy involves a woman knowing she is pregnant, but purposely hiding from others. Concealment may occur after a period of denial of pregnancy. Denial of pregnancy has several subtypes: pervasive denial, affective denial, and psychotic denial. In cases of pervasive denial, the existence of the pregnancy and the pregnancy’s emotional significance is outside the woman’s awareness. Alternatively, in affective denial, she is intellectually aware that she is pregnant but makes little emotional or physical preparation. In the rarest form, psychotic denial, a woman with a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia may intermittently deny her pregnancy. This may be correlated with a history of custody loss.10,11 Unlike denial of other medical conditions, in cases of denial of pregnancy, there will exist a very specific point in time (delivery) when the reality of the baby confronts the woman. Risks in cases of hidden pregnancies include those from lack of prenatal care and an assisted delivery as well as neonaticide. An FBI study12 of law enforcement files found most neonaticide offenders were single young women with no criminal or psychological history. A caveat is that in the rare cases in which a woman with psychotic illness commits neonaticide, she may have different characteristics from those generally reported.13

Motives

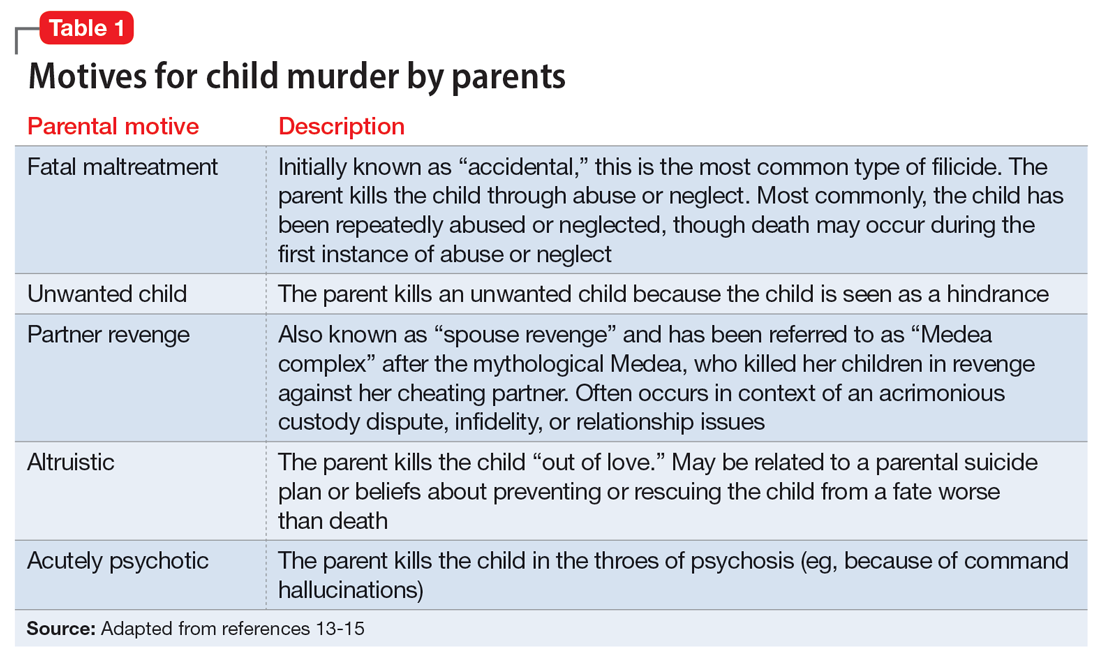

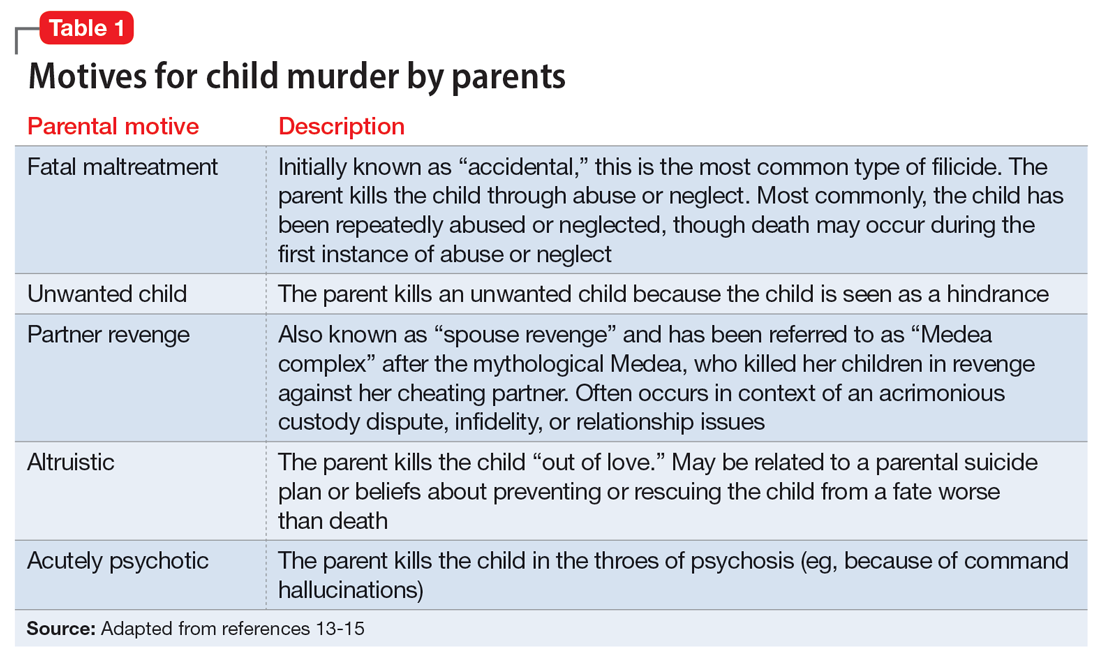

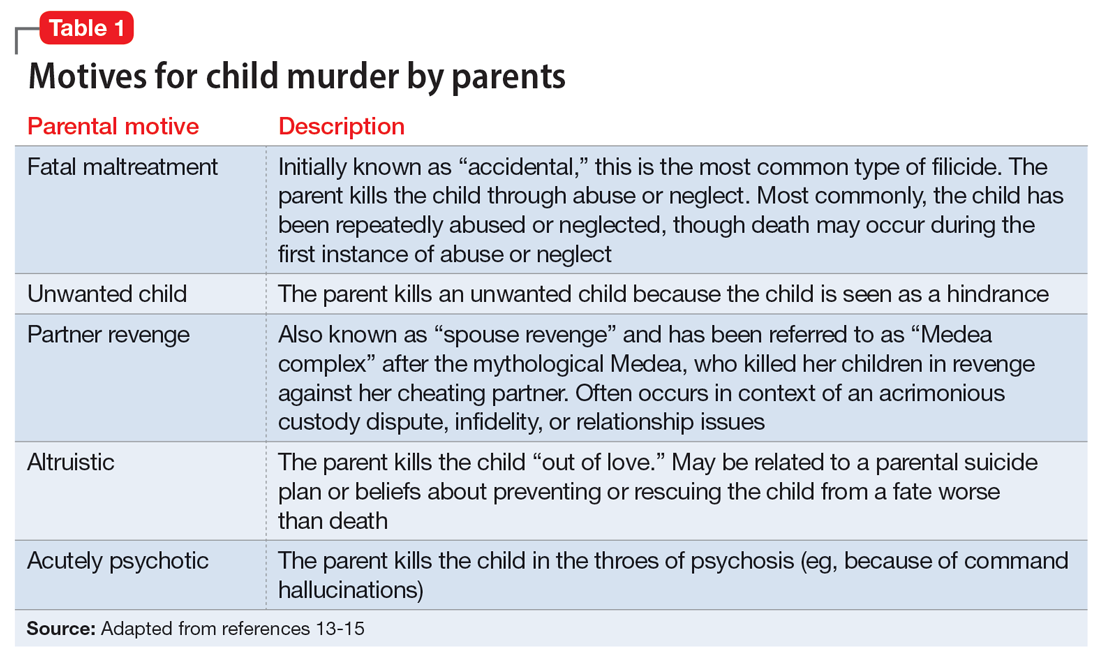

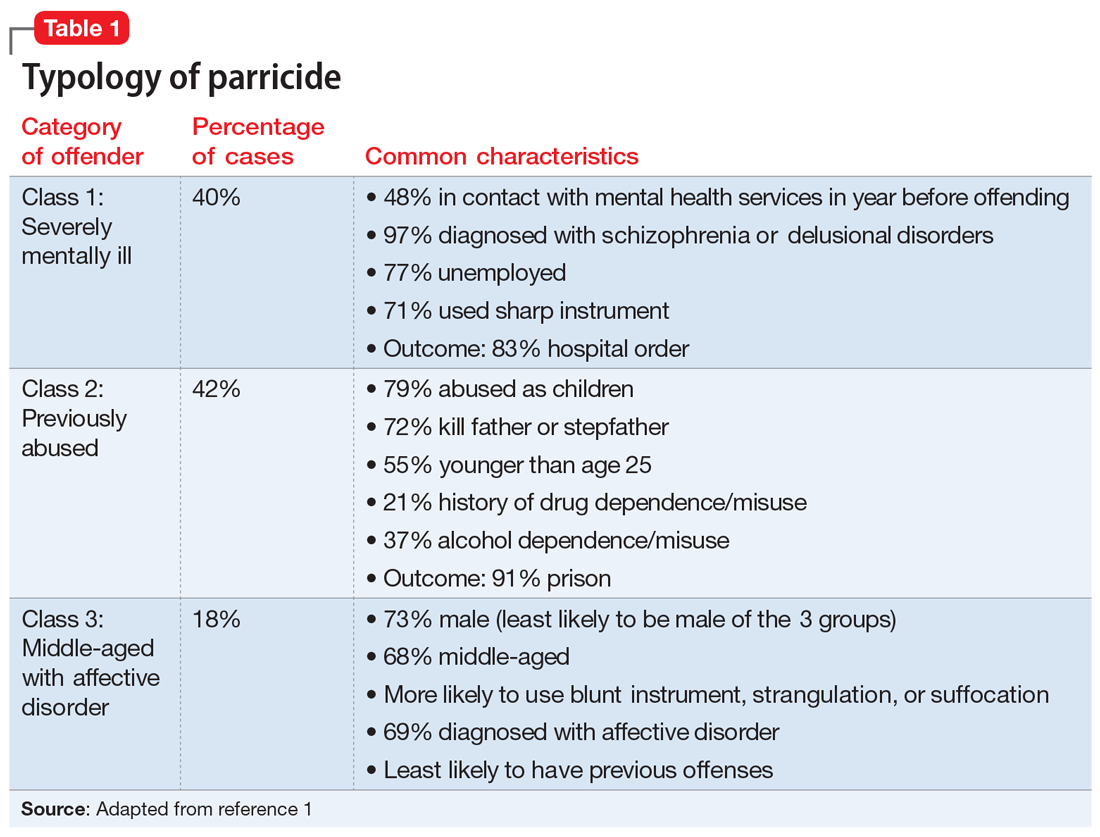

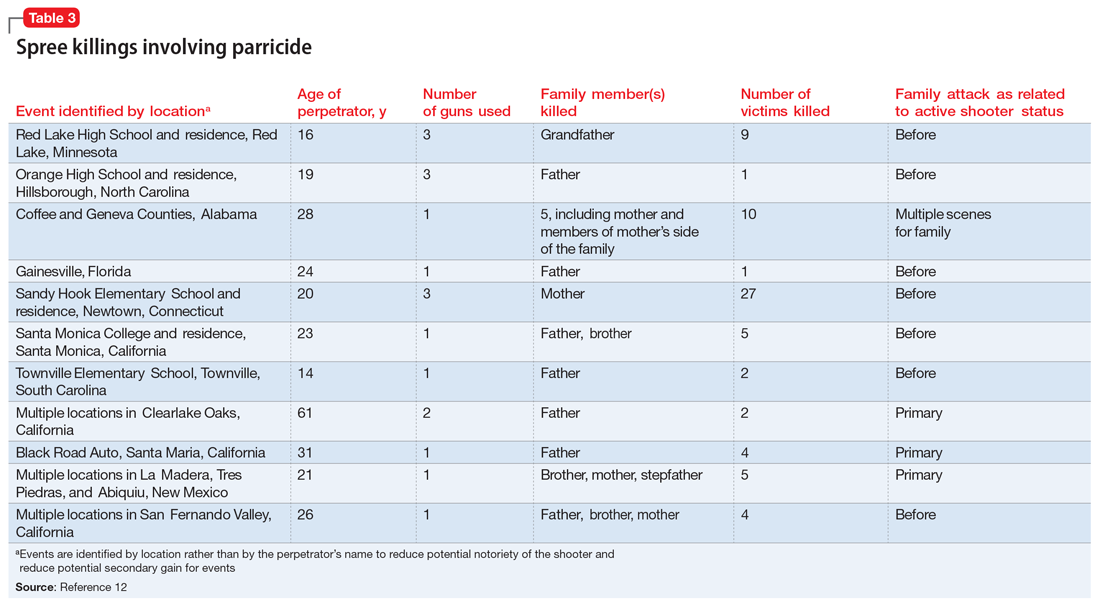

Fathers and mothers have a similar set of motives for killing their child (Table 113-15). Motives are critical to understand not only within forensics, but also for prevention. In performing assessments after a filicide, forensic psychiatrists must be mindful of gender bias.7,16 Resnick15 initially described 5 motives based on his 1969 review of the world literature. Our work5,17 has subsequently further explored these motives.

In child homicides from “fatal maltreatment,” the child has often been a chronic victim of abuse or neglect. National American data indicate that approximately 2 per 100,000 children are killed from child maltreatment annually. Of note in conceptualizing prevention, out of the same population of 100,000, there will be 471 referrals to Child Protective Services and 91 substantiated cases.18 However, only a minority of children who die from maltreatment had previous Child Protective Services involvement. While a child may be killed by fatal maltreatment at any age, one-half are younger than age 1, and three-quarters are younger than age 3.18 In rare cases, a parent who engages in medical child abuse (including factitious disorder imposed upon another) kills the child. Depending on the location and whether or not the death appeared to be intended, parents who kill because of fatal maltreatment might face charges of various levels of murder or manslaughter.

“Unwanted child” homicides occur when the parent has determined that they do not want to have the child, especially in comparison to another need or want. Unwanted child motive is the most common in neonaticide cases, occurring after a hidden pregnancy.4

Continue to: In "partner revenge" cases...

In “partner revenge” cases, parenting disputes, a custody battle, infidelity, or a difficult relationship breakup is often present. The parent wants to make the other parent suffer, and does so by killing their child. A parent may make statements such as “If I can’t have [the child], no one can,” and the child is used as a pawn.

In the final 2 motives—“altruistic” and “acutely psychotic”—mental illness is common. These are the populations we tend to find in samples of filicide-suicide cases where the parent has killed themselves and their child, and those found not guilty by reason of insanity.5,17 Altruistic filicide has been described as “murder out of love.” How can a parent kill their child out of love? Our research has shown several ways. First, the parent may be severely depressed and suicidal. They may be planning their own suicide, and as a parent who loves their child, they plan to take their child with them in death and not leave them alone in the “cruel world” that they themselves are departing. Or the parent may believe they are killing the child out of love to prevent or relieve the child’s suffering. The psychotic parent may believe that a terrible fate will befall their child, and they are killing them “gently.” For example, the parent may believe the child will be tortured or sex trafficked. Some parents may believe that their child has a devastating disease and think they would be better off dead. (Similar thinking of misguided altruism is seen in some cases of intimate partner homicide among older adults.19)

Alternatively, in rare cases of acutely psychotic filicide, parents with psychosis kill their child with no comprehensible motive. For example, they may be in a postictal state or may hear a command hallucination from God in the context of their psychosis.15

Myths vs realities of filicide

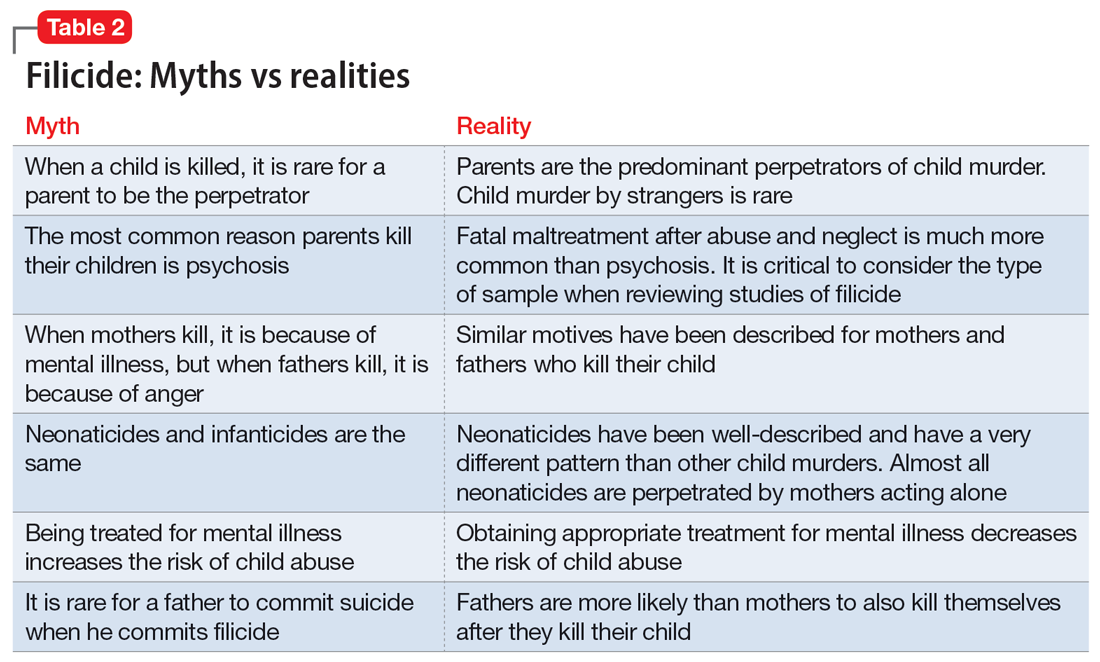

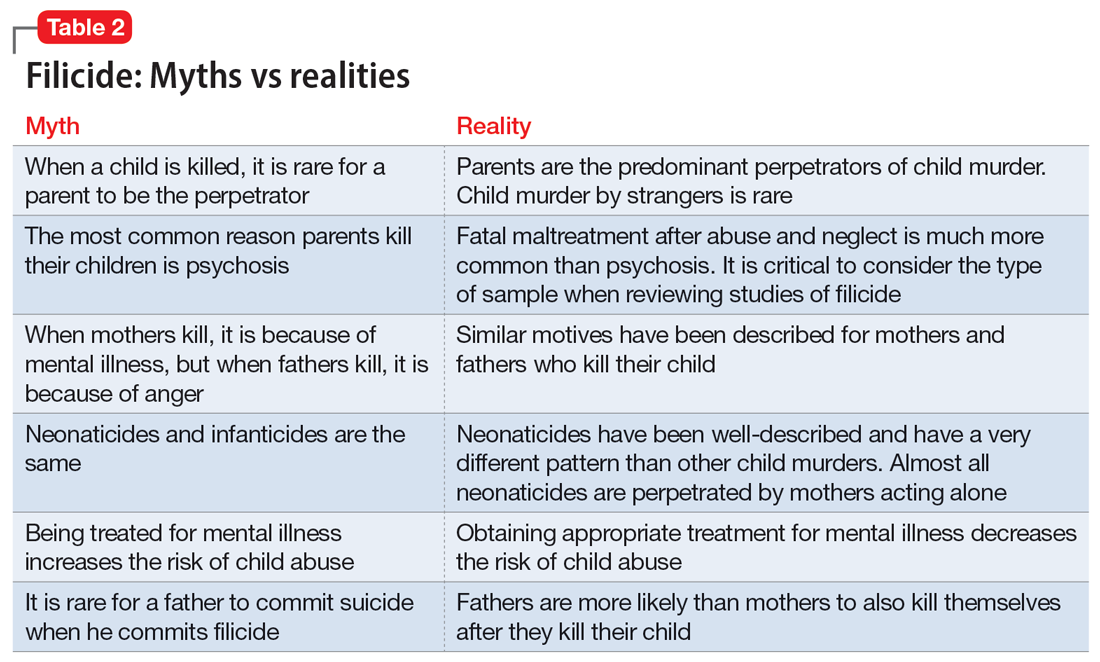

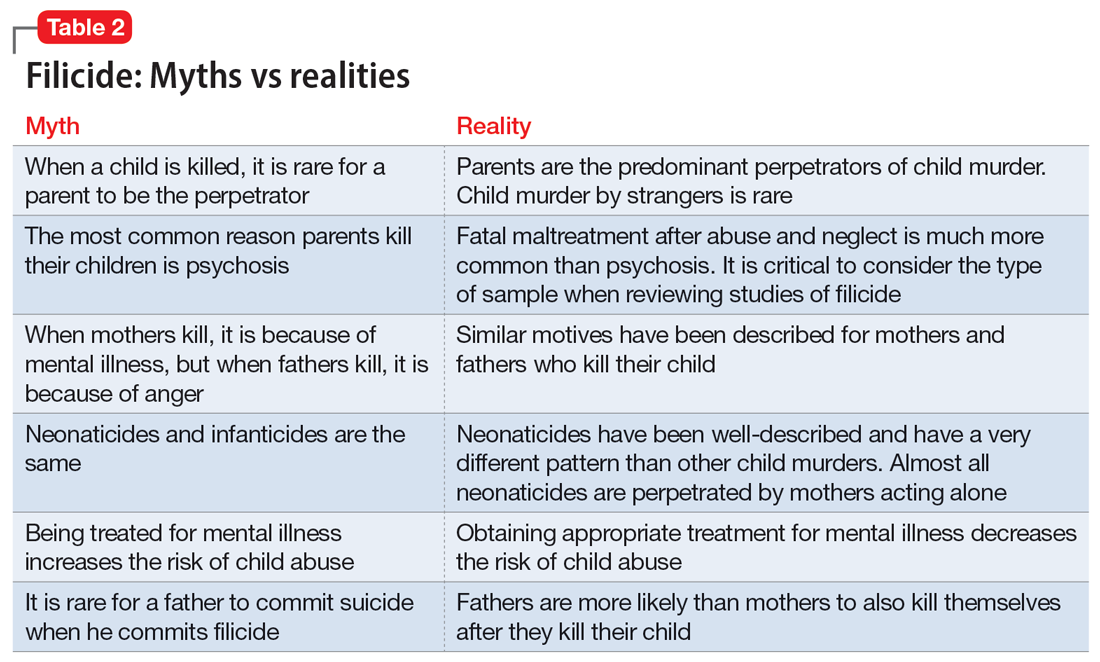

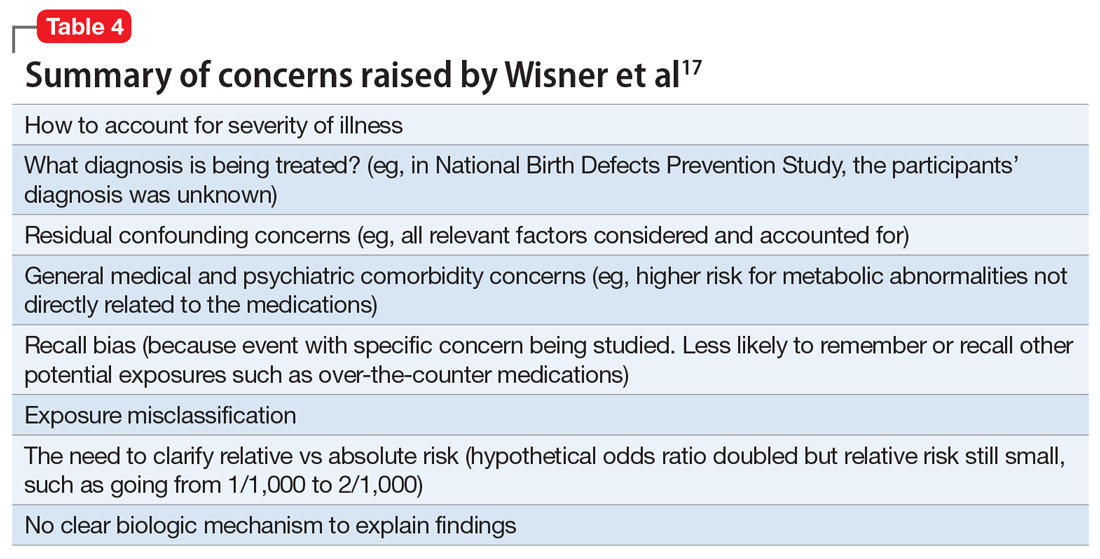

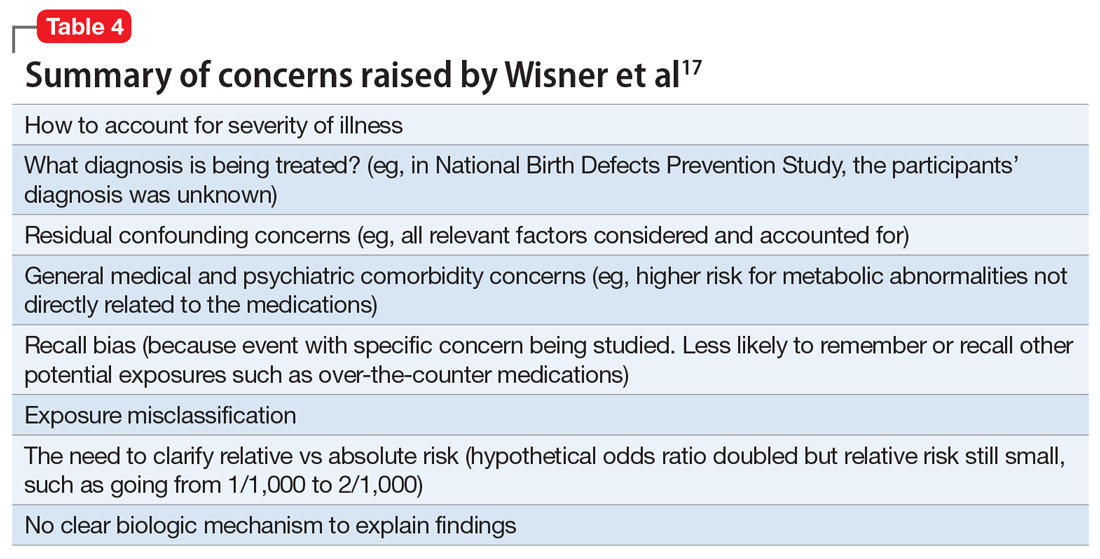

Common myths vs the realities of filicide are noted in Table 2. There are issues with believing these myths. For example, if we believe that most parents who kill their child have mental illness, this conflates mental illness and child homicide in our minds as well as the mind of the public. This can lead to further stigmatization of mental illness, and a lack of help-seeking behaviors because parents experiencing psychiatric symptoms may be afraid that if they report their symptoms, their child will be removed by Child Protective Services. However, treated mental illness decreases the risks of child abuse, similar to how treating mental illness decreases risks of other types of violence.20,21

Focusing on prevention

On a local level, we need to understand these tragedies to better understand prevention. To this end, across the United States, counties have Child Fatality Review teams.22 These teams are a partnership across sectors and disciplines, including professionals from health services, law enforcement, and social services—among others—working together to understand cases and consider preventive strategies and additional services needed within our communities.

Continue to: When conceptualizing prevention...

When conceptualizing prevention of child murder by parents, we can think of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. This means we want to encourage healthy families and healthy relationships within the family, as well as screening for risk and targeting interventions for families that have experienced difficulties, as well as for parents who have mental illness or substance use disorders.

Understanding the motive behind an individual committing filicide is also critical so that we do not conflate filicide and mental illness. Conflating these concepts leads to increased stigmatization and less help-seeking behavior.

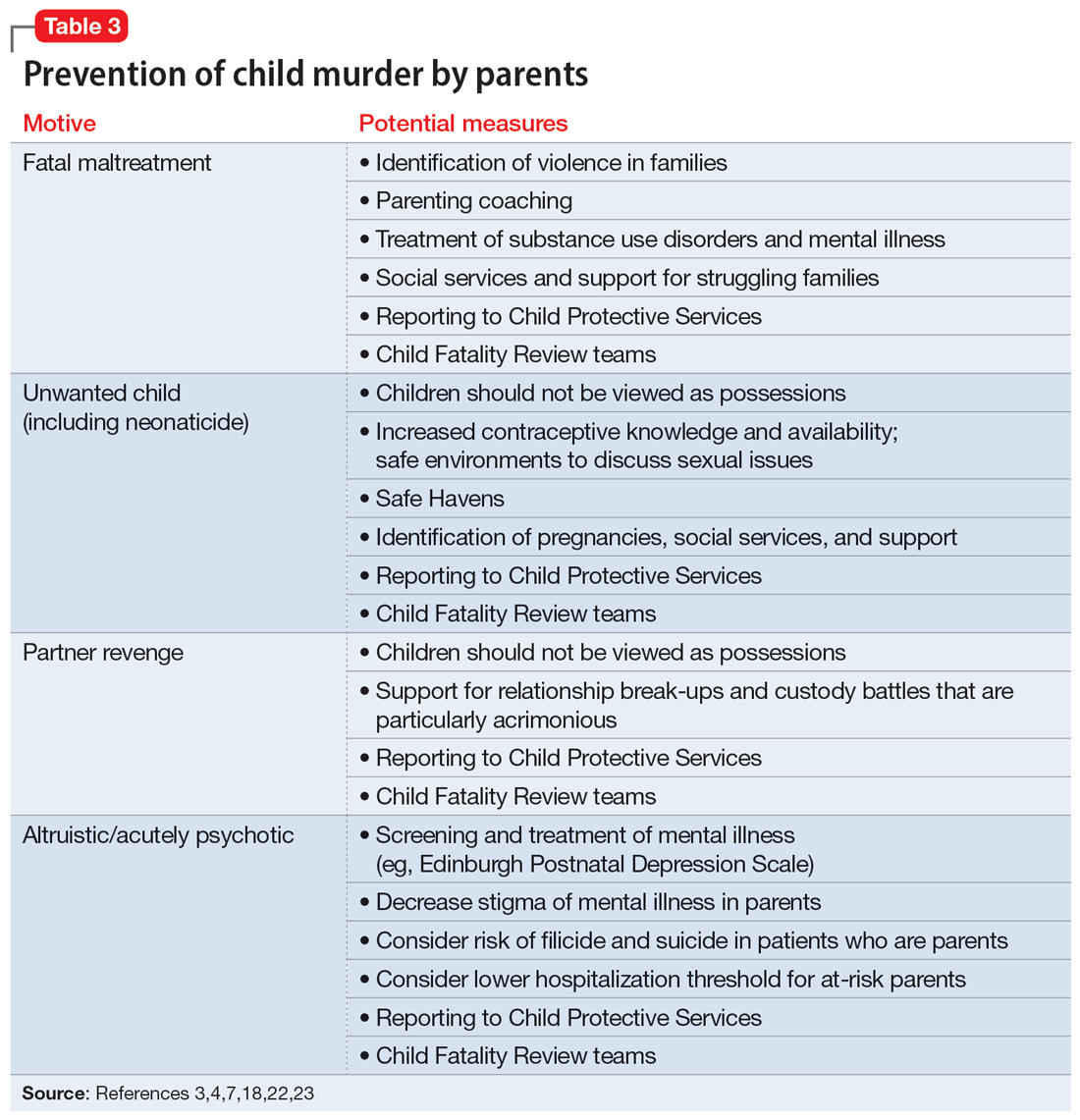

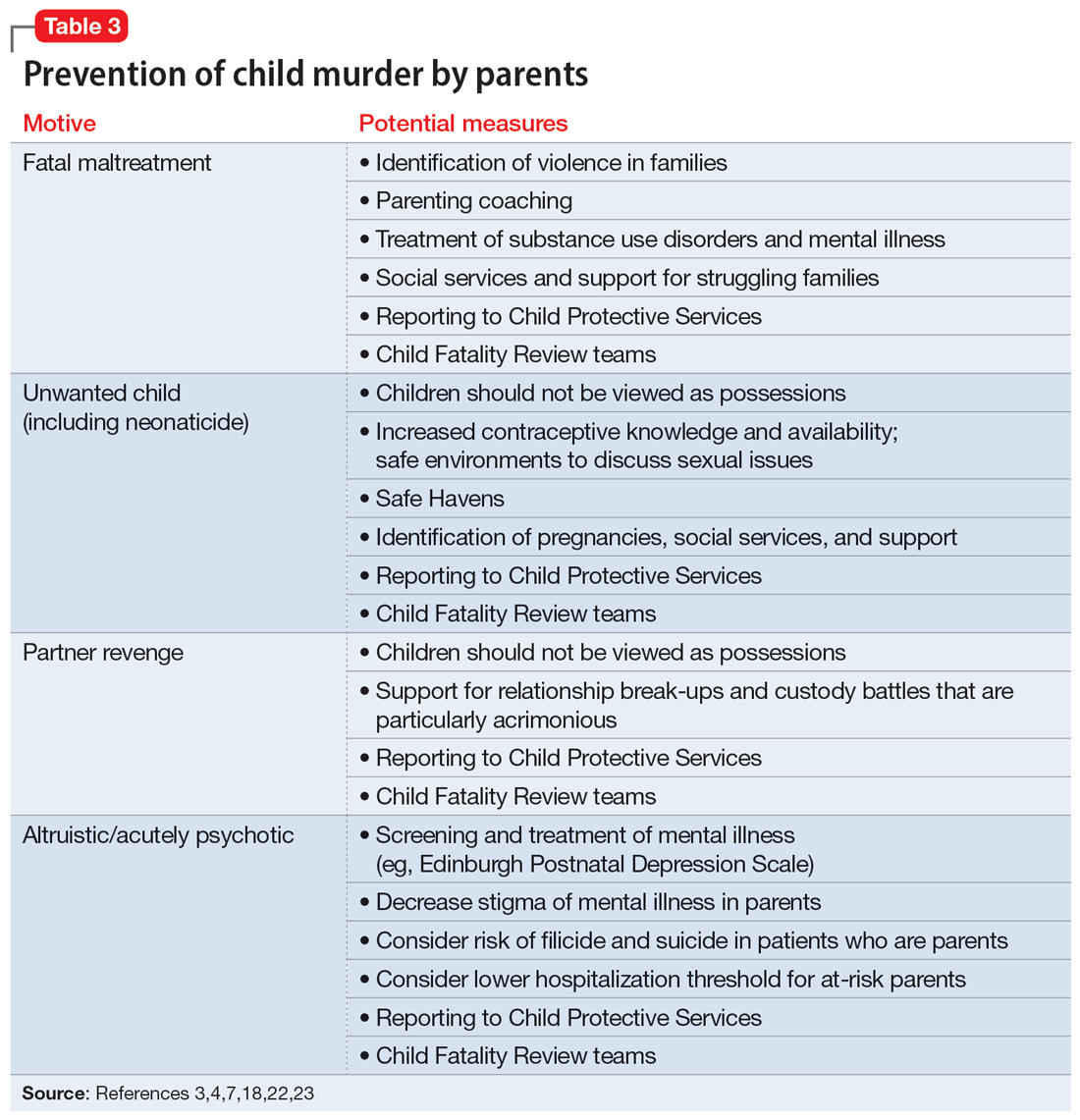

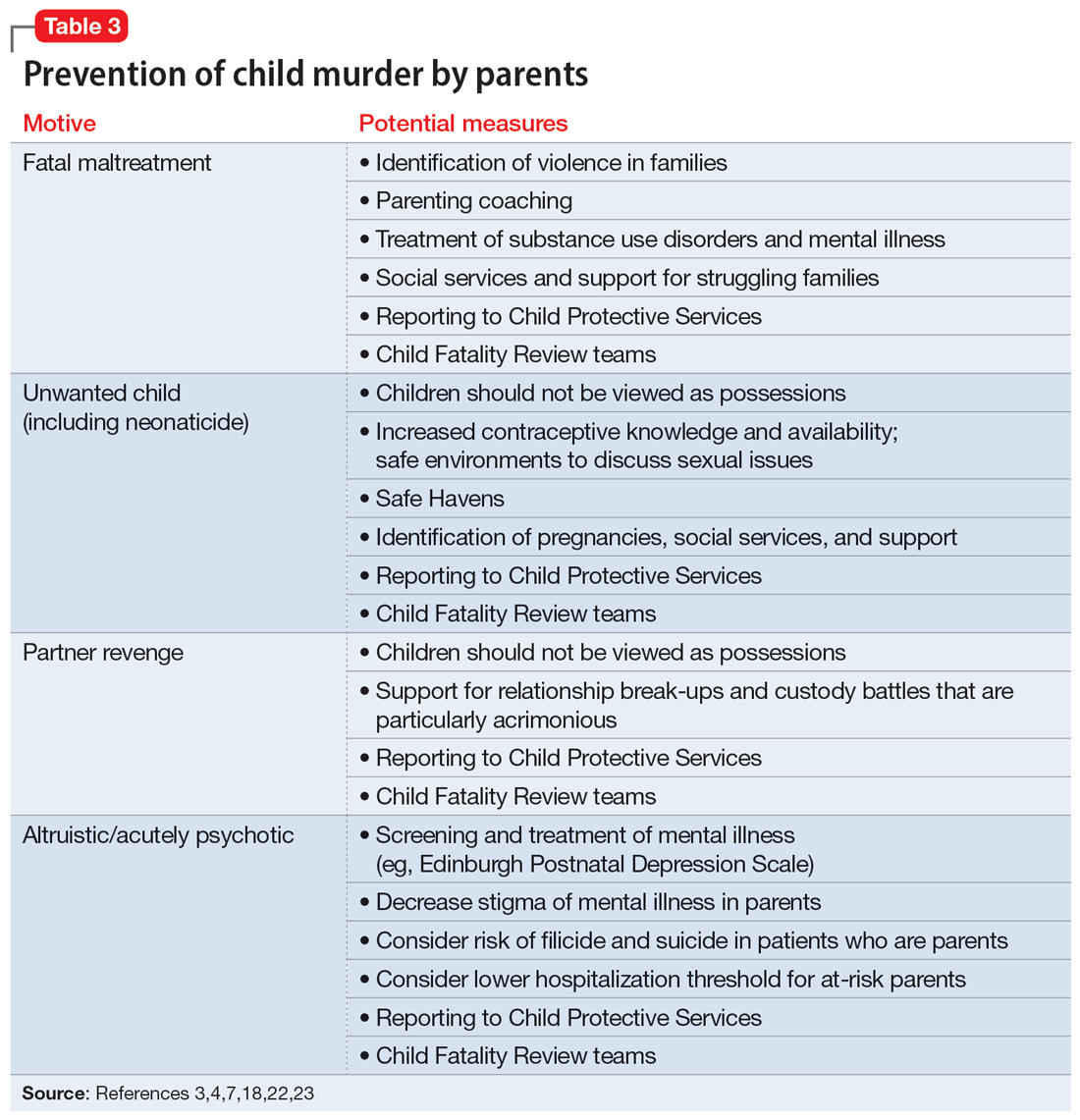

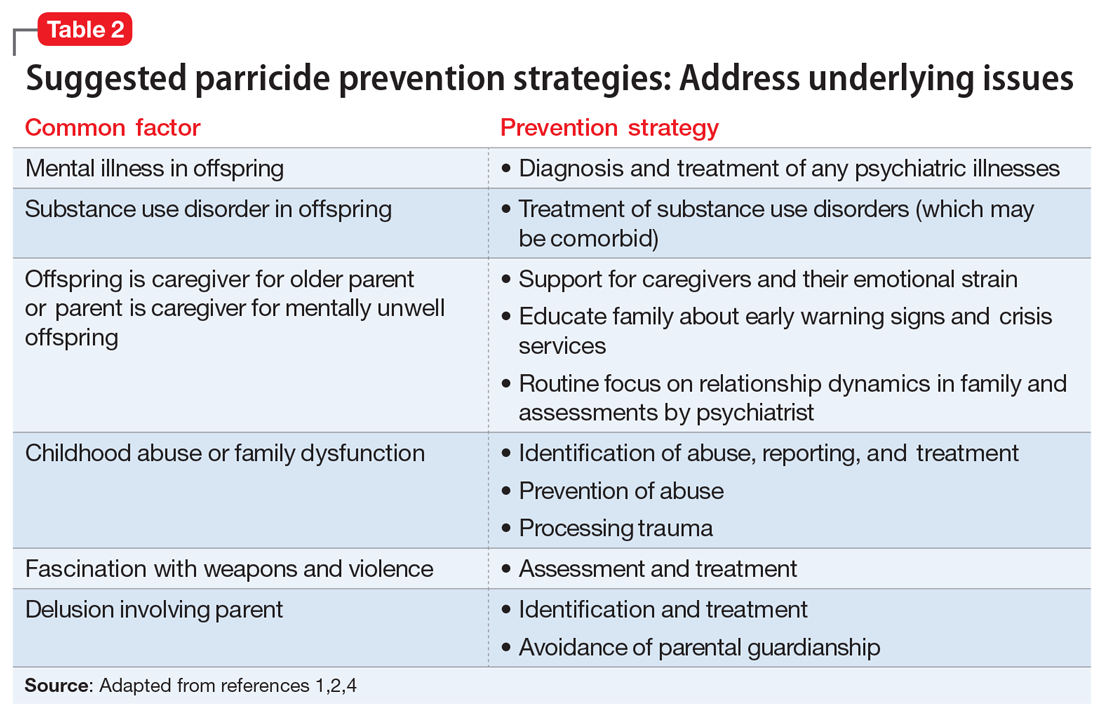

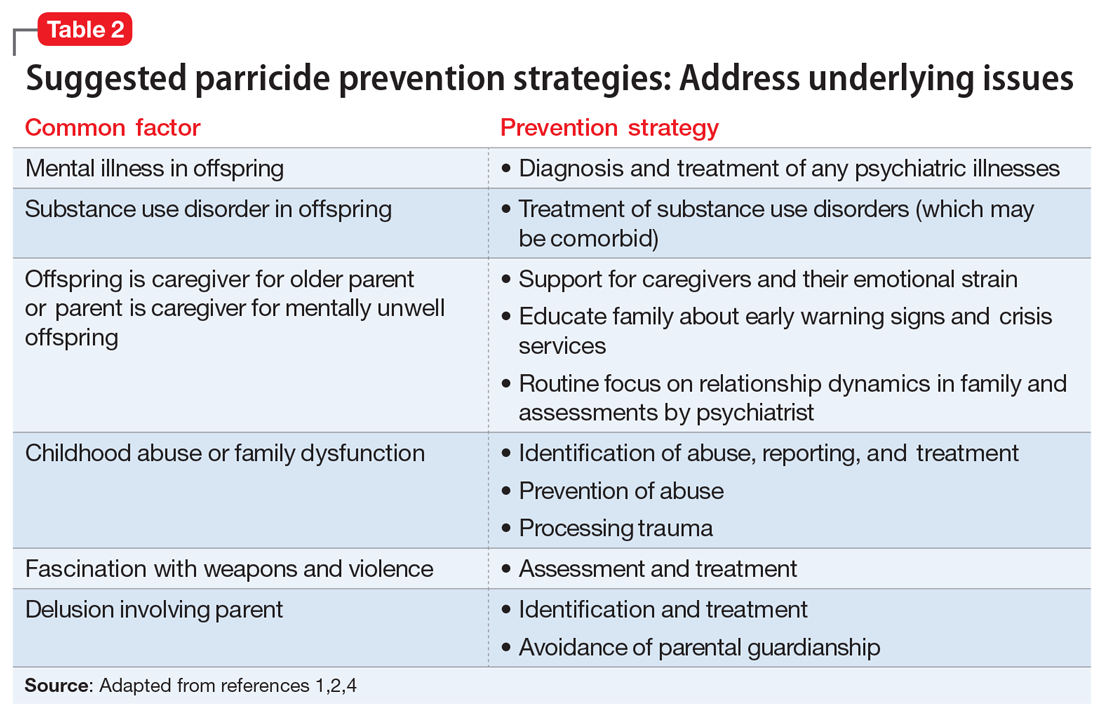

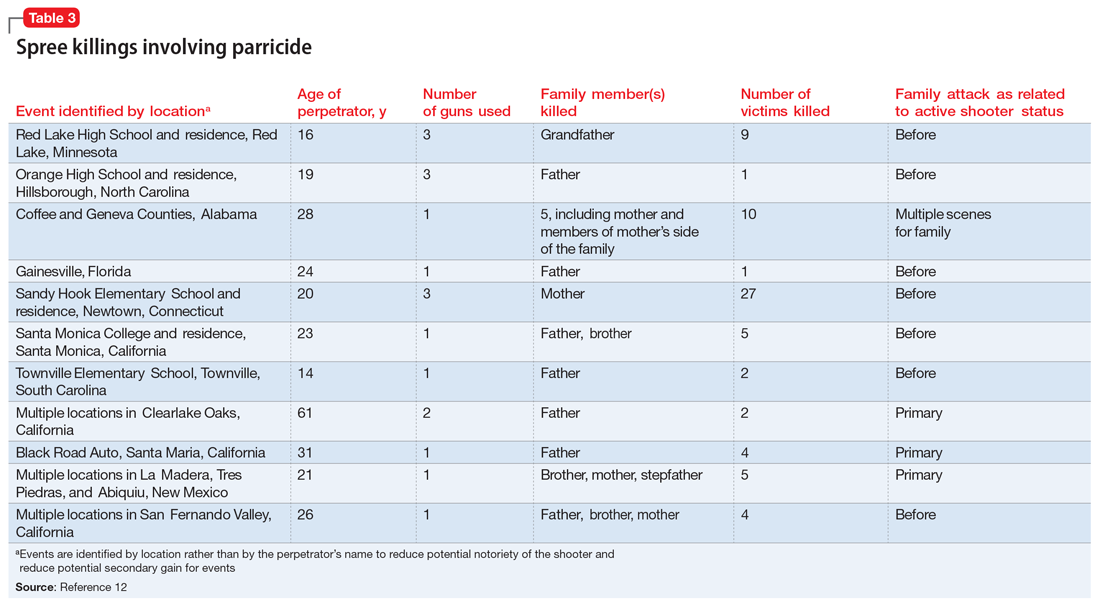

Table 33,4,7,18,22,23 describes the importance of understanding the motives for child murder by a parent in order to conceptualize appropriate prevention. Prevention efforts for 1 type of child murder will not necessarily help prevent murders that occur due to the other motives. Regarding prevention for fatal maltreatment cases, poor parenting skills, including inappropriate expressions of discipline, anger, and frustration, are common. In some cases, substance abuse is involved or the parent was acutely mentally unwell. Reporting to Child Protective Services can be helpful, but as previously noted, it is difficult to ascertain which cases will lead to a homicide. Recommendations from Child Fatality Review teams also are valuable.

Though many parents have frustrations with their children or thoughts of child harm, the act of filicide is rare, and individual cases may be difficult to predict. Regarding prediction, some mothers who committed filicide saw their psychiatrist within days to weeks before the murders.17 A small New Zealand study found that psychotic mothers reported no plans for killing their children in advance, whereas depressed mothers had contemplated the killing for days to weeks.24

Several studies have asked mothers about thoughts of harming their child. Among mothers with colicky infants, 70% reported “explicit aggressive thoughts and fantasies” while 26% had “infanticidal thoughts” during a colic episode.25 Another study26 found that among depressed mothers of infants and toddlers, 41% revealed thoughts of harming their child. Women with postpartum depression preferred not to share infanticidal thoughts with their doctor but were more likely to disclose that they were having suicidal thoughts in order to get needed help.27 Psychiatrists need to feel comfortable asking mothers about their coping skills, their suicidal thoughts, and their filicidal thoughts.14,23,28 Screening and treatment of mental illness is critical. Postpartum psychosis is well-known to pose an elevated risk of filicide and suicide.23 Obsessive-compulsive disorder may cause a parent to ruminate over ego-dystonic child harm but should be treated and the risk conceptualized very differently than in postpartum psychosis.23,29 Screening for postpartum depression and appropriate treatment of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period decrease risk.30

Continue to: Regarding prevention of neonaticide...

Regarding prevention of neonaticide, Safe Haven laws, baby boxes, anonymous birth options, and increased contraceptive information and availability can help decrease the risk of this well-defined type of homicide.4 Safe Haven laws originated from Child Fatality Review teams.24 Though each state has its own variation, in general, parents can drop off an unharmed unwanted infant into Safe Havens in their state, which may include hospitals, police stations, or fire stations. In general, the mother remains anonymous and has immunity from prosecution for (safe) abandonment. There are drawbacks, such as lack of information regarding adoption and paternal rights. Safe Haven laws do not prevent all deaths and all unsafe abandonments. Baby boxes and baby hatches are used in various nations, including in Europe, and in some places have been used for centuries. In anonymous birth options, such as in France, a mother is not identified but is able to give birth at a hospital. This can decrease the risk from unattended delivery, but many women with denial of pregnancy report that they did not realize when they were about to give birth.4

Bottom Line

Knowledge about the intersection of mental illness and filicide can help in prevention. Parents who experience mental health concerns should be encouraged to obtain needed treatment, which aids prevention. However, many other factors elevate the risk of child murder by parents.

Related Resources

- National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention. https://ncfrp.org/

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/overview/federal-agencies/

1. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psych. 2005;162(9):1578-1587.

2. Mariano TY, Chan HC, Myers WC. Toward a more holistic understanding of filicide: a multidisciplinary analysis of 32 years of US arrest data [published corrections appears in Forensic Sci Int. 2014;245:92-94]. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;236:46-53.

3. Hatters Friedman S, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):137-141.

4. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and considerations for prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32(1):43-47.

5. Hatters Friedman S, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):496-504.

6. Daly M, Wilson M. Is the “Cinderella effect” controversial? A case study of evolution-minded research and critiques thereof. In: Crawford C, Krebs D, eds. Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008:383-400.

7. Friedman SH. Fathers and filicide: Mental illness and outcomes. In: Wong G, Parnham G, eds. Infanticide and Filicide: Foundations in Maternal Mental Health Forensics. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:85-107.

8. West SG, Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Fathers who kill their children: an analysis of the literature. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):463-468.

9. Putkonen H, Amon S, Eronen M, et al. Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics--a comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abuse Neglect. 2011;35(5):319-328.

10. Miller LJ. Denial of pregnancy. In: Spinelli MG, ed. Infanticide: Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers Who Kill. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2003:81-104.

11. Friedman SH, Heneghan A, Rosenthal M. Characteristics of women who deny or conceal pregnancy. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):117-122.

12. Beyer K, Mack SM, Shelton JL. Investigative analysis of neonaticide: an exploratory study. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(4):522-535.

13. Putkonen H, Weizmann-Henelius G, Collander J, et al. Neonaticides may be more preventable and heterogeneous than previously thought--neonaticides in Finland 1980-2000. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(1):15-23.

14. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder and mental illness in parents: implications for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):587-588.

15. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126(3):325-334.

16. Friedman SH. Searching for the whole truth: considering culture and gender in forensic psychiatric practice. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2023;51(1):23-34.

17. Friedman SH, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: an examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(6):1466-1471.

18. Ash P. Fatal maltreatment and child abuse turned to murder. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. Group for the Advancement Psychiatry; 2018.

19. Friedman SH, Appel JM. Murder in the family: intimate partner homicide in the elderly. Psychiatric News. 2018. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.12a21

20. Friedman SH, McEwan MV. Treated mental illness and the risk of child abuse perpetration. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):211-216.

21. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

22. Hatters Friedman S, Beaman JW, Friedman JB. Fatality review and the role of the forensic psychiatrist. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2021;49(3):396-405.

23. Friedman SH, Prakash C, Nagle-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

24. Stanton J, Simpson AI, Wouldes T. A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(11):1451-1460.

25. Levitzky S, Cooper R. Infant colic syndrome—maternal fantasies of aggression and infanticide. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(7):395-400.

26. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(1-2):21-28.

27. Barr JA, Beck CT. Infanticide secrets: qualitative study on postpartum depression. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(12):1716-1717.e5.

28. Friedman SH, Sorrentino RM, Stankowski JE, et al. Psychiatrists’ knowledge about maternal filicidal thoughts. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):106-110.

29. Booth BD, Friedman SH, Curry S, et al. Obsessions of child murder: underrecognized manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(1):66-74.

30. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):30-36.

Deaths of children who are killed by their parents often make the news. Cases of maternal infanticide may be particularly shocking, since women are expected to be selfless nurturers. Yet when a child is murdered, the most common perpetrator is their parent, and mothers and fathers kill at similar rates.1

As psychiatrists, we may see these cases in the news and worry about the risks of our own patients killing their children. In approximately 500 cases annually, an American parent is arrested for the homicide of their child.2 This is not even the entire story, since a large percentage of such cases end in suicide—and no arrest. This article reviews the reasons parents kill their children, and considers common characteristics of these parents, dispelling some myths, before discussing the importance of prevention efforts.

Types of child murder by parents

Child murder by parents is termed filicide. Infanticide has various meanings but often refers to the murder of a child younger than age 1. Approximately 2 dozen nations (but not the United States) have Infanticide Acts that decrease the penalty for mothers who kill their young child.3 Neonaticide refers to murder of the infant at birth or in the first day of life.4

Epidemiology and common characteristics

Approximately 15%—or 1 in 7 murders with an arrest—is a filicide.2 The younger the child, the greater the risk, but older children are killed as well.2 Internationally, fathers and mothers are found to kill at similar rates. For other types of homicide, offenders are overwhelmingly male. This makes child murder by parents the singular type of murder in which women and men perpetrate in equal numbers. Fathers are more likely than mothers to also commit suicide after they kill their children.5 The “Cinderella effect” refers to the elevated risk of a stepchild being killed compared to the risk for a biological child.6

In the general international population, mothers who commit filicide tend to have multiple stressors and limited resources. They may be socially isolated and may be victims themselves as well as potentially experiencing substance abuse.1 Some mothers view the child they killed as abnormal.

Less research has been conducted about fathers who kill. Fathers are more likely to also commit partner homicide.5,7 They are more likely to complete filicide-suicide and use firearms or other violent means.5,7-9 Fathers may have a history of violence, substance abuse, and/or mental illness.7

Neonaticide

Mothers are the most common perpetrator of neonaticide.4 It is unusual for a father to be involved in a neonaticide, or for the father and mother to perpetrate the act together. Rates of neonaticide are considered underestimates because of the number of hidden pregnancies, hidden corpses, and the difficulty that forensic pathologists may have in determining whether a baby was born alive or dead.

Continue to: Perpetrators of neonaticide...

Perpetrators of neonaticide tend to be single, relatively young women acting alone. They often live with their parents and are fearful of the repercussions of being pregnant. Pregnancies are often hidden, with no prenatal care. This includes both denial and concealment of pregnancy.4 Perpetrators of neonaticide commonly lack a premorbid serious mental illness, though after the homicide they may develop anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or adjustment disorder.4 (Individuals who unwittingly find a murdered baby’s corpse may also be at risk of PTSD.)

Hidden pregnancies may be due to concealment or denial of pregnancy.10,11 Concealment of pregnancy involves a woman knowing she is pregnant, but purposely hiding from others. Concealment may occur after a period of denial of pregnancy. Denial of pregnancy has several subtypes: pervasive denial, affective denial, and psychotic denial. In cases of pervasive denial, the existence of the pregnancy and the pregnancy’s emotional significance is outside the woman’s awareness. Alternatively, in affective denial, she is intellectually aware that she is pregnant but makes little emotional or physical preparation. In the rarest form, psychotic denial, a woman with a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia may intermittently deny her pregnancy. This may be correlated with a history of custody loss.10,11 Unlike denial of other medical conditions, in cases of denial of pregnancy, there will exist a very specific point in time (delivery) when the reality of the baby confronts the woman. Risks in cases of hidden pregnancies include those from lack of prenatal care and an assisted delivery as well as neonaticide. An FBI study12 of law enforcement files found most neonaticide offenders were single young women with no criminal or psychological history. A caveat is that in the rare cases in which a woman with psychotic illness commits neonaticide, she may have different characteristics from those generally reported.13

Motives

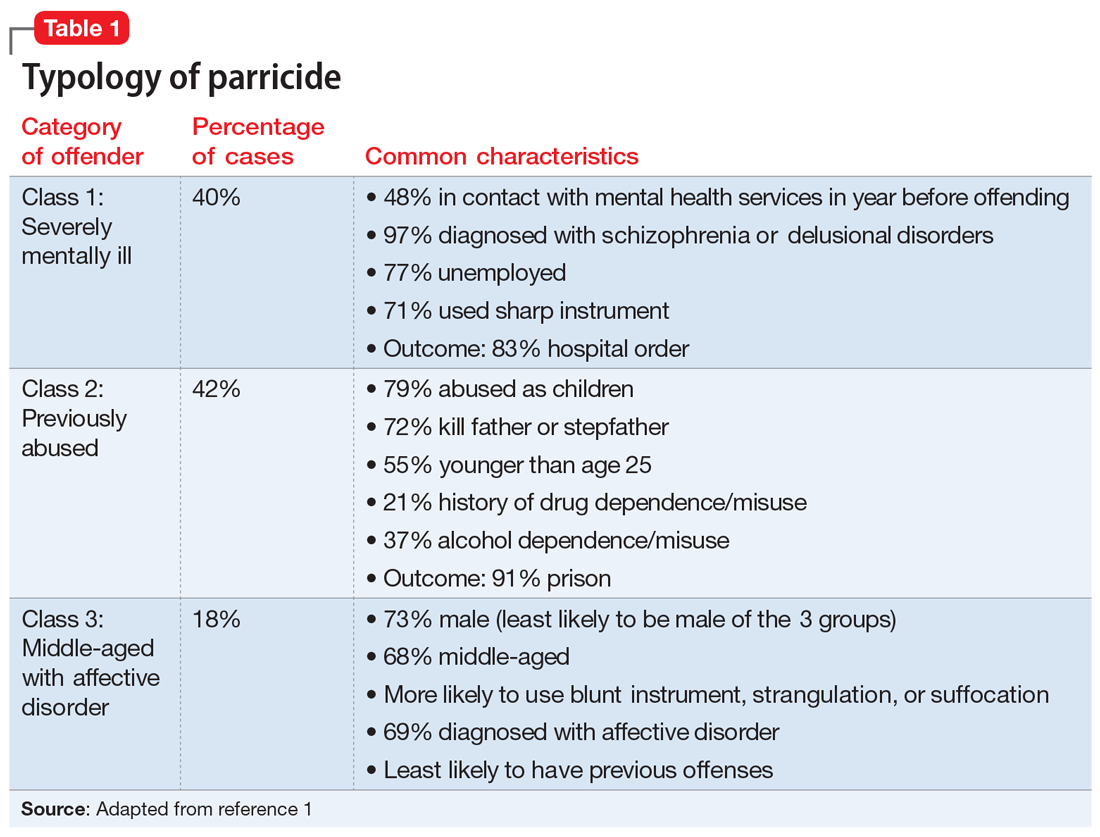

Fathers and mothers have a similar set of motives for killing their child (Table 113-15). Motives are critical to understand not only within forensics, but also for prevention. In performing assessments after a filicide, forensic psychiatrists must be mindful of gender bias.7,16 Resnick15 initially described 5 motives based on his 1969 review of the world literature. Our work5,17 has subsequently further explored these motives.

In child homicides from “fatal maltreatment,” the child has often been a chronic victim of abuse or neglect. National American data indicate that approximately 2 per 100,000 children are killed from child maltreatment annually. Of note in conceptualizing prevention, out of the same population of 100,000, there will be 471 referrals to Child Protective Services and 91 substantiated cases.18 However, only a minority of children who die from maltreatment had previous Child Protective Services involvement. While a child may be killed by fatal maltreatment at any age, one-half are younger than age 1, and three-quarters are younger than age 3.18 In rare cases, a parent who engages in medical child abuse (including factitious disorder imposed upon another) kills the child. Depending on the location and whether or not the death appeared to be intended, parents who kill because of fatal maltreatment might face charges of various levels of murder or manslaughter.

“Unwanted child” homicides occur when the parent has determined that they do not want to have the child, especially in comparison to another need or want. Unwanted child motive is the most common in neonaticide cases, occurring after a hidden pregnancy.4

Continue to: In "partner revenge" cases...

In “partner revenge” cases, parenting disputes, a custody battle, infidelity, or a difficult relationship breakup is often present. The parent wants to make the other parent suffer, and does so by killing their child. A parent may make statements such as “If I can’t have [the child], no one can,” and the child is used as a pawn.

In the final 2 motives—“altruistic” and “acutely psychotic”—mental illness is common. These are the populations we tend to find in samples of filicide-suicide cases where the parent has killed themselves and their child, and those found not guilty by reason of insanity.5,17 Altruistic filicide has been described as “murder out of love.” How can a parent kill their child out of love? Our research has shown several ways. First, the parent may be severely depressed and suicidal. They may be planning their own suicide, and as a parent who loves their child, they plan to take their child with them in death and not leave them alone in the “cruel world” that they themselves are departing. Or the parent may believe they are killing the child out of love to prevent or relieve the child’s suffering. The psychotic parent may believe that a terrible fate will befall their child, and they are killing them “gently.” For example, the parent may believe the child will be tortured or sex trafficked. Some parents may believe that their child has a devastating disease and think they would be better off dead. (Similar thinking of misguided altruism is seen in some cases of intimate partner homicide among older adults.19)

Alternatively, in rare cases of acutely psychotic filicide, parents with psychosis kill their child with no comprehensible motive. For example, they may be in a postictal state or may hear a command hallucination from God in the context of their psychosis.15

Myths vs realities of filicide

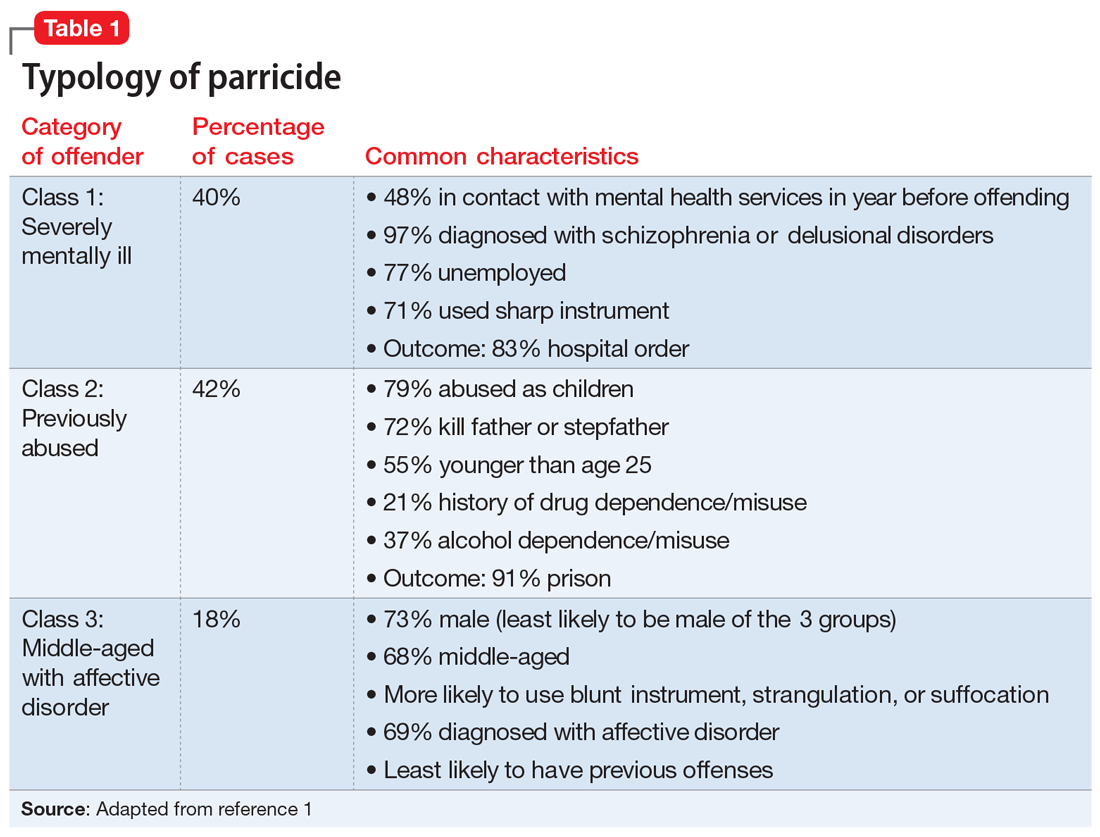

Common myths vs the realities of filicide are noted in Table 2. There are issues with believing these myths. For example, if we believe that most parents who kill their child have mental illness, this conflates mental illness and child homicide in our minds as well as the mind of the public. This can lead to further stigmatization of mental illness, and a lack of help-seeking behaviors because parents experiencing psychiatric symptoms may be afraid that if they report their symptoms, their child will be removed by Child Protective Services. However, treated mental illness decreases the risks of child abuse, similar to how treating mental illness decreases risks of other types of violence.20,21

Focusing on prevention

On a local level, we need to understand these tragedies to better understand prevention. To this end, across the United States, counties have Child Fatality Review teams.22 These teams are a partnership across sectors and disciplines, including professionals from health services, law enforcement, and social services—among others—working together to understand cases and consider preventive strategies and additional services needed within our communities.

Continue to: When conceptualizing prevention...

When conceptualizing prevention of child murder by parents, we can think of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. This means we want to encourage healthy families and healthy relationships within the family, as well as screening for risk and targeting interventions for families that have experienced difficulties, as well as for parents who have mental illness or substance use disorders.

Understanding the motive behind an individual committing filicide is also critical so that we do not conflate filicide and mental illness. Conflating these concepts leads to increased stigmatization and less help-seeking behavior.

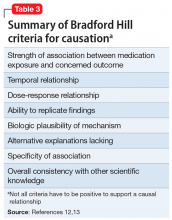

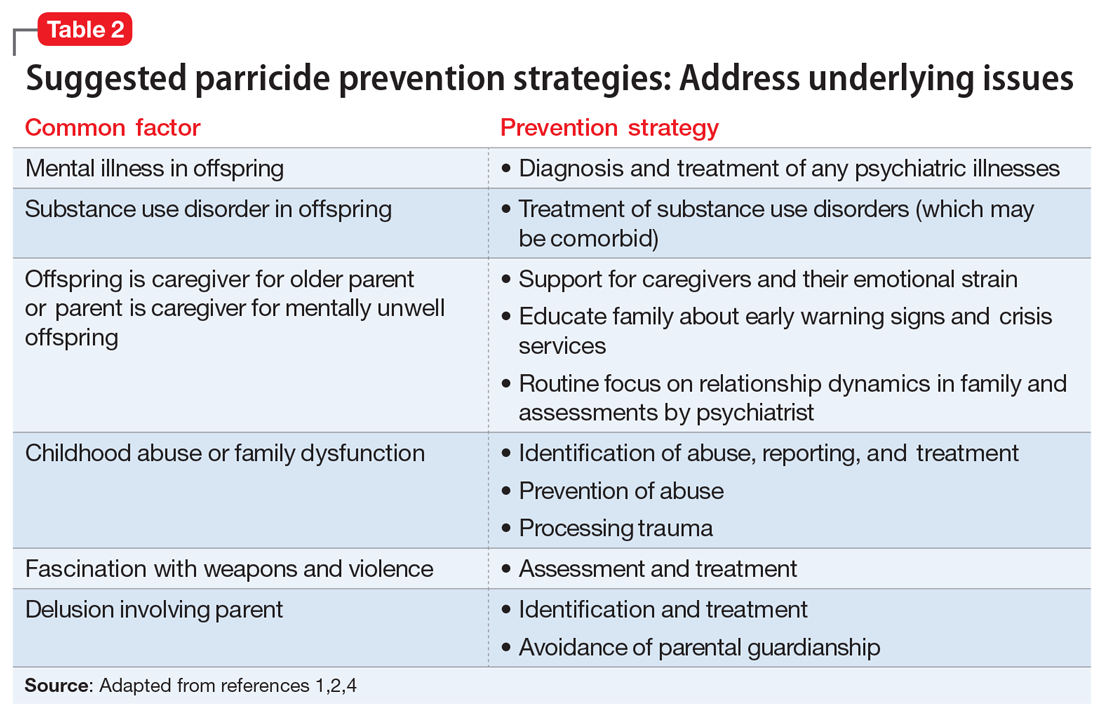

Table 33,4,7,18,22,23 describes the importance of understanding the motives for child murder by a parent in order to conceptualize appropriate prevention. Prevention efforts for 1 type of child murder will not necessarily help prevent murders that occur due to the other motives. Regarding prevention for fatal maltreatment cases, poor parenting skills, including inappropriate expressions of discipline, anger, and frustration, are common. In some cases, substance abuse is involved or the parent was acutely mentally unwell. Reporting to Child Protective Services can be helpful, but as previously noted, it is difficult to ascertain which cases will lead to a homicide. Recommendations from Child Fatality Review teams also are valuable.

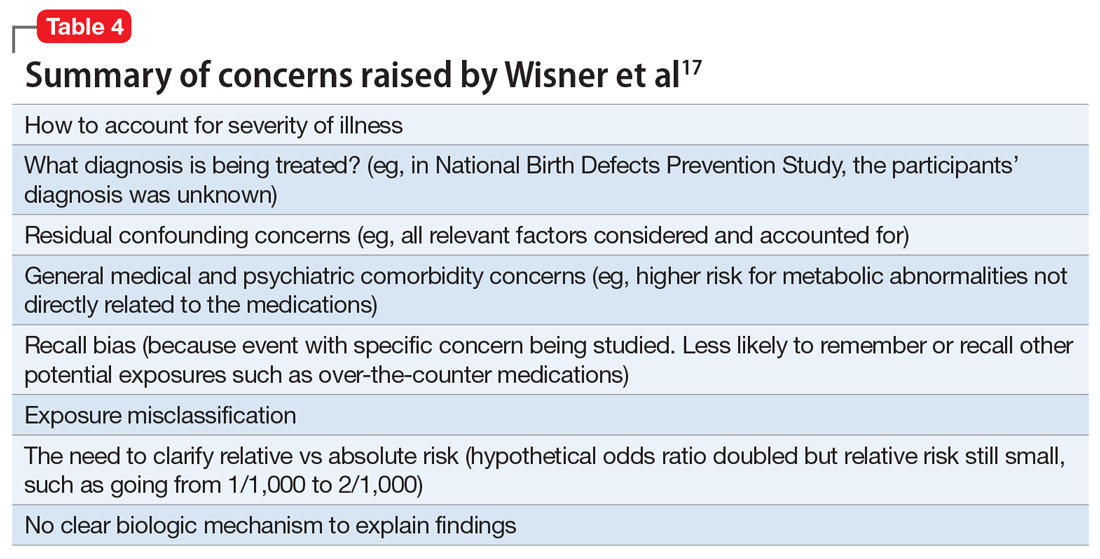

Though many parents have frustrations with their children or thoughts of child harm, the act of filicide is rare, and individual cases may be difficult to predict. Regarding prediction, some mothers who committed filicide saw their psychiatrist within days to weeks before the murders.17 A small New Zealand study found that psychotic mothers reported no plans for killing their children in advance, whereas depressed mothers had contemplated the killing for days to weeks.24

Several studies have asked mothers about thoughts of harming their child. Among mothers with colicky infants, 70% reported “explicit aggressive thoughts and fantasies” while 26% had “infanticidal thoughts” during a colic episode.25 Another study26 found that among depressed mothers of infants and toddlers, 41% revealed thoughts of harming their child. Women with postpartum depression preferred not to share infanticidal thoughts with their doctor but were more likely to disclose that they were having suicidal thoughts in order to get needed help.27 Psychiatrists need to feel comfortable asking mothers about their coping skills, their suicidal thoughts, and their filicidal thoughts.14,23,28 Screening and treatment of mental illness is critical. Postpartum psychosis is well-known to pose an elevated risk of filicide and suicide.23 Obsessive-compulsive disorder may cause a parent to ruminate over ego-dystonic child harm but should be treated and the risk conceptualized very differently than in postpartum psychosis.23,29 Screening for postpartum depression and appropriate treatment of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period decrease risk.30

Continue to: Regarding prevention of neonaticide...

Regarding prevention of neonaticide, Safe Haven laws, baby boxes, anonymous birth options, and increased contraceptive information and availability can help decrease the risk of this well-defined type of homicide.4 Safe Haven laws originated from Child Fatality Review teams.24 Though each state has its own variation, in general, parents can drop off an unharmed unwanted infant into Safe Havens in their state, which may include hospitals, police stations, or fire stations. In general, the mother remains anonymous and has immunity from prosecution for (safe) abandonment. There are drawbacks, such as lack of information regarding adoption and paternal rights. Safe Haven laws do not prevent all deaths and all unsafe abandonments. Baby boxes and baby hatches are used in various nations, including in Europe, and in some places have been used for centuries. In anonymous birth options, such as in France, a mother is not identified but is able to give birth at a hospital. This can decrease the risk from unattended delivery, but many women with denial of pregnancy report that they did not realize when they were about to give birth.4

Bottom Line

Knowledge about the intersection of mental illness and filicide can help in prevention. Parents who experience mental health concerns should be encouraged to obtain needed treatment, which aids prevention. However, many other factors elevate the risk of child murder by parents.

Related Resources

- National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention. https://ncfrp.org/

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/overview/federal-agencies/

Deaths of children who are killed by their parents often make the news. Cases of maternal infanticide may be particularly shocking, since women are expected to be selfless nurturers. Yet when a child is murdered, the most common perpetrator is their parent, and mothers and fathers kill at similar rates.1

As psychiatrists, we may see these cases in the news and worry about the risks of our own patients killing their children. In approximately 500 cases annually, an American parent is arrested for the homicide of their child.2 This is not even the entire story, since a large percentage of such cases end in suicide—and no arrest. This article reviews the reasons parents kill their children, and considers common characteristics of these parents, dispelling some myths, before discussing the importance of prevention efforts.

Types of child murder by parents

Child murder by parents is termed filicide. Infanticide has various meanings but often refers to the murder of a child younger than age 1. Approximately 2 dozen nations (but not the United States) have Infanticide Acts that decrease the penalty for mothers who kill their young child.3 Neonaticide refers to murder of the infant at birth or in the first day of life.4

Epidemiology and common characteristics

Approximately 15%—or 1 in 7 murders with an arrest—is a filicide.2 The younger the child, the greater the risk, but older children are killed as well.2 Internationally, fathers and mothers are found to kill at similar rates. For other types of homicide, offenders are overwhelmingly male. This makes child murder by parents the singular type of murder in which women and men perpetrate in equal numbers. Fathers are more likely than mothers to also commit suicide after they kill their children.5 The “Cinderella effect” refers to the elevated risk of a stepchild being killed compared to the risk for a biological child.6

In the general international population, mothers who commit filicide tend to have multiple stressors and limited resources. They may be socially isolated and may be victims themselves as well as potentially experiencing substance abuse.1 Some mothers view the child they killed as abnormal.

Less research has been conducted about fathers who kill. Fathers are more likely to also commit partner homicide.5,7 They are more likely to complete filicide-suicide and use firearms or other violent means.5,7-9 Fathers may have a history of violence, substance abuse, and/or mental illness.7

Neonaticide

Mothers are the most common perpetrator of neonaticide.4 It is unusual for a father to be involved in a neonaticide, or for the father and mother to perpetrate the act together. Rates of neonaticide are considered underestimates because of the number of hidden pregnancies, hidden corpses, and the difficulty that forensic pathologists may have in determining whether a baby was born alive or dead.

Continue to: Perpetrators of neonaticide...

Perpetrators of neonaticide tend to be single, relatively young women acting alone. They often live with their parents and are fearful of the repercussions of being pregnant. Pregnancies are often hidden, with no prenatal care. This includes both denial and concealment of pregnancy.4 Perpetrators of neonaticide commonly lack a premorbid serious mental illness, though after the homicide they may develop anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or adjustment disorder.4 (Individuals who unwittingly find a murdered baby’s corpse may also be at risk of PTSD.)

Hidden pregnancies may be due to concealment or denial of pregnancy.10,11 Concealment of pregnancy involves a woman knowing she is pregnant, but purposely hiding from others. Concealment may occur after a period of denial of pregnancy. Denial of pregnancy has several subtypes: pervasive denial, affective denial, and psychotic denial. In cases of pervasive denial, the existence of the pregnancy and the pregnancy’s emotional significance is outside the woman’s awareness. Alternatively, in affective denial, she is intellectually aware that she is pregnant but makes little emotional or physical preparation. In the rarest form, psychotic denial, a woman with a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia may intermittently deny her pregnancy. This may be correlated with a history of custody loss.10,11 Unlike denial of other medical conditions, in cases of denial of pregnancy, there will exist a very specific point in time (delivery) when the reality of the baby confronts the woman. Risks in cases of hidden pregnancies include those from lack of prenatal care and an assisted delivery as well as neonaticide. An FBI study12 of law enforcement files found most neonaticide offenders were single young women with no criminal or psychological history. A caveat is that in the rare cases in which a woman with psychotic illness commits neonaticide, she may have different characteristics from those generally reported.13

Motives

Fathers and mothers have a similar set of motives for killing their child (Table 113-15). Motives are critical to understand not only within forensics, but also for prevention. In performing assessments after a filicide, forensic psychiatrists must be mindful of gender bias.7,16 Resnick15 initially described 5 motives based on his 1969 review of the world literature. Our work5,17 has subsequently further explored these motives.

In child homicides from “fatal maltreatment,” the child has often been a chronic victim of abuse or neglect. National American data indicate that approximately 2 per 100,000 children are killed from child maltreatment annually. Of note in conceptualizing prevention, out of the same population of 100,000, there will be 471 referrals to Child Protective Services and 91 substantiated cases.18 However, only a minority of children who die from maltreatment had previous Child Protective Services involvement. While a child may be killed by fatal maltreatment at any age, one-half are younger than age 1, and three-quarters are younger than age 3.18 In rare cases, a parent who engages in medical child abuse (including factitious disorder imposed upon another) kills the child. Depending on the location and whether or not the death appeared to be intended, parents who kill because of fatal maltreatment might face charges of various levels of murder or manslaughter.

“Unwanted child” homicides occur when the parent has determined that they do not want to have the child, especially in comparison to another need or want. Unwanted child motive is the most common in neonaticide cases, occurring after a hidden pregnancy.4

Continue to: In "partner revenge" cases...

In “partner revenge” cases, parenting disputes, a custody battle, infidelity, or a difficult relationship breakup is often present. The parent wants to make the other parent suffer, and does so by killing their child. A parent may make statements such as “If I can’t have [the child], no one can,” and the child is used as a pawn.

In the final 2 motives—“altruistic” and “acutely psychotic”—mental illness is common. These are the populations we tend to find in samples of filicide-suicide cases where the parent has killed themselves and their child, and those found not guilty by reason of insanity.5,17 Altruistic filicide has been described as “murder out of love.” How can a parent kill their child out of love? Our research has shown several ways. First, the parent may be severely depressed and suicidal. They may be planning their own suicide, and as a parent who loves their child, they plan to take their child with them in death and not leave them alone in the “cruel world” that they themselves are departing. Or the parent may believe they are killing the child out of love to prevent or relieve the child’s suffering. The psychotic parent may believe that a terrible fate will befall their child, and they are killing them “gently.” For example, the parent may believe the child will be tortured or sex trafficked. Some parents may believe that their child has a devastating disease and think they would be better off dead. (Similar thinking of misguided altruism is seen in some cases of intimate partner homicide among older adults.19)

Alternatively, in rare cases of acutely psychotic filicide, parents with psychosis kill their child with no comprehensible motive. For example, they may be in a postictal state or may hear a command hallucination from God in the context of their psychosis.15

Myths vs realities of filicide

Common myths vs the realities of filicide are noted in Table 2. There are issues with believing these myths. For example, if we believe that most parents who kill their child have mental illness, this conflates mental illness and child homicide in our minds as well as the mind of the public. This can lead to further stigmatization of mental illness, and a lack of help-seeking behaviors because parents experiencing psychiatric symptoms may be afraid that if they report their symptoms, their child will be removed by Child Protective Services. However, treated mental illness decreases the risks of child abuse, similar to how treating mental illness decreases risks of other types of violence.20,21

Focusing on prevention

On a local level, we need to understand these tragedies to better understand prevention. To this end, across the United States, counties have Child Fatality Review teams.22 These teams are a partnership across sectors and disciplines, including professionals from health services, law enforcement, and social services—among others—working together to understand cases and consider preventive strategies and additional services needed within our communities.

Continue to: When conceptualizing prevention...

When conceptualizing prevention of child murder by parents, we can think of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. This means we want to encourage healthy families and healthy relationships within the family, as well as screening for risk and targeting interventions for families that have experienced difficulties, as well as for parents who have mental illness or substance use disorders.

Understanding the motive behind an individual committing filicide is also critical so that we do not conflate filicide and mental illness. Conflating these concepts leads to increased stigmatization and less help-seeking behavior.

Table 33,4,7,18,22,23 describes the importance of understanding the motives for child murder by a parent in order to conceptualize appropriate prevention. Prevention efforts for 1 type of child murder will not necessarily help prevent murders that occur due to the other motives. Regarding prevention for fatal maltreatment cases, poor parenting skills, including inappropriate expressions of discipline, anger, and frustration, are common. In some cases, substance abuse is involved or the parent was acutely mentally unwell. Reporting to Child Protective Services can be helpful, but as previously noted, it is difficult to ascertain which cases will lead to a homicide. Recommendations from Child Fatality Review teams also are valuable.

Though many parents have frustrations with their children or thoughts of child harm, the act of filicide is rare, and individual cases may be difficult to predict. Regarding prediction, some mothers who committed filicide saw their psychiatrist within days to weeks before the murders.17 A small New Zealand study found that psychotic mothers reported no plans for killing their children in advance, whereas depressed mothers had contemplated the killing for days to weeks.24

Several studies have asked mothers about thoughts of harming their child. Among mothers with colicky infants, 70% reported “explicit aggressive thoughts and fantasies” while 26% had “infanticidal thoughts” during a colic episode.25 Another study26 found that among depressed mothers of infants and toddlers, 41% revealed thoughts of harming their child. Women with postpartum depression preferred not to share infanticidal thoughts with their doctor but were more likely to disclose that they were having suicidal thoughts in order to get needed help.27 Psychiatrists need to feel comfortable asking mothers about their coping skills, their suicidal thoughts, and their filicidal thoughts.14,23,28 Screening and treatment of mental illness is critical. Postpartum psychosis is well-known to pose an elevated risk of filicide and suicide.23 Obsessive-compulsive disorder may cause a parent to ruminate over ego-dystonic child harm but should be treated and the risk conceptualized very differently than in postpartum psychosis.23,29 Screening for postpartum depression and appropriate treatment of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period decrease risk.30

Continue to: Regarding prevention of neonaticide...

Regarding prevention of neonaticide, Safe Haven laws, baby boxes, anonymous birth options, and increased contraceptive information and availability can help decrease the risk of this well-defined type of homicide.4 Safe Haven laws originated from Child Fatality Review teams.24 Though each state has its own variation, in general, parents can drop off an unharmed unwanted infant into Safe Havens in their state, which may include hospitals, police stations, or fire stations. In general, the mother remains anonymous and has immunity from prosecution for (safe) abandonment. There are drawbacks, such as lack of information regarding adoption and paternal rights. Safe Haven laws do not prevent all deaths and all unsafe abandonments. Baby boxes and baby hatches are used in various nations, including in Europe, and in some places have been used for centuries. In anonymous birth options, such as in France, a mother is not identified but is able to give birth at a hospital. This can decrease the risk from unattended delivery, but many women with denial of pregnancy report that they did not realize when they were about to give birth.4

Bottom Line

Knowledge about the intersection of mental illness and filicide can help in prevention. Parents who experience mental health concerns should be encouraged to obtain needed treatment, which aids prevention. However, many other factors elevate the risk of child murder by parents.

Related Resources

- National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention. https://ncfrp.org/

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/overview/federal-agencies/

1. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psych. 2005;162(9):1578-1587.

2. Mariano TY, Chan HC, Myers WC. Toward a more holistic understanding of filicide: a multidisciplinary analysis of 32 years of US arrest data [published corrections appears in Forensic Sci Int. 2014;245:92-94]. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;236:46-53.

3. Hatters Friedman S, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):137-141.

4. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and considerations for prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32(1):43-47.

5. Hatters Friedman S, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):496-504.

6. Daly M, Wilson M. Is the “Cinderella effect” controversial? A case study of evolution-minded research and critiques thereof. In: Crawford C, Krebs D, eds. Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008:383-400.

7. Friedman SH. Fathers and filicide: Mental illness and outcomes. In: Wong G, Parnham G, eds. Infanticide and Filicide: Foundations in Maternal Mental Health Forensics. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:85-107.

8. West SG, Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Fathers who kill their children: an analysis of the literature. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):463-468.

9. Putkonen H, Amon S, Eronen M, et al. Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics--a comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abuse Neglect. 2011;35(5):319-328.

10. Miller LJ. Denial of pregnancy. In: Spinelli MG, ed. Infanticide: Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers Who Kill. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2003:81-104.

11. Friedman SH, Heneghan A, Rosenthal M. Characteristics of women who deny or conceal pregnancy. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):117-122.

12. Beyer K, Mack SM, Shelton JL. Investigative analysis of neonaticide: an exploratory study. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(4):522-535.

13. Putkonen H, Weizmann-Henelius G, Collander J, et al. Neonaticides may be more preventable and heterogeneous than previously thought--neonaticides in Finland 1980-2000. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(1):15-23.

14. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder and mental illness in parents: implications for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):587-588.

15. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126(3):325-334.

16. Friedman SH. Searching for the whole truth: considering culture and gender in forensic psychiatric practice. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2023;51(1):23-34.

17. Friedman SH, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: an examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(6):1466-1471.

18. Ash P. Fatal maltreatment and child abuse turned to murder. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. Group for the Advancement Psychiatry; 2018.

19. Friedman SH, Appel JM. Murder in the family: intimate partner homicide in the elderly. Psychiatric News. 2018. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.12a21

20. Friedman SH, McEwan MV. Treated mental illness and the risk of child abuse perpetration. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):211-216.

21. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

22. Hatters Friedman S, Beaman JW, Friedman JB. Fatality review and the role of the forensic psychiatrist. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2021;49(3):396-405.

23. Friedman SH, Prakash C, Nagle-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

24. Stanton J, Simpson AI, Wouldes T. A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(11):1451-1460.

25. Levitzky S, Cooper R. Infant colic syndrome—maternal fantasies of aggression and infanticide. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(7):395-400.

26. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(1-2):21-28.

27. Barr JA, Beck CT. Infanticide secrets: qualitative study on postpartum depression. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(12):1716-1717.e5.

28. Friedman SH, Sorrentino RM, Stankowski JE, et al. Psychiatrists’ knowledge about maternal filicidal thoughts. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):106-110.

29. Booth BD, Friedman SH, Curry S, et al. Obsessions of child murder: underrecognized manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(1):66-74.

30. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):30-36.

1. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psych. 2005;162(9):1578-1587.

2. Mariano TY, Chan HC, Myers WC. Toward a more holistic understanding of filicide: a multidisciplinary analysis of 32 years of US arrest data [published corrections appears in Forensic Sci Int. 2014;245:92-94]. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;236:46-53.

3. Hatters Friedman S, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):137-141.

4. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and considerations for prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32(1):43-47.

5. Hatters Friedman S, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):496-504.

6. Daly M, Wilson M. Is the “Cinderella effect” controversial? A case study of evolution-minded research and critiques thereof. In: Crawford C, Krebs D, eds. Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008:383-400.

7. Friedman SH. Fathers and filicide: Mental illness and outcomes. In: Wong G, Parnham G, eds. Infanticide and Filicide: Foundations in Maternal Mental Health Forensics. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:85-107.

8. West SG, Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Fathers who kill their children: an analysis of the literature. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):463-468.

9. Putkonen H, Amon S, Eronen M, et al. Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics--a comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abuse Neglect. 2011;35(5):319-328.

10. Miller LJ. Denial of pregnancy. In: Spinelli MG, ed. Infanticide: Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers Who Kill. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2003:81-104.

11. Friedman SH, Heneghan A, Rosenthal M. Characteristics of women who deny or conceal pregnancy. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):117-122.

12. Beyer K, Mack SM, Shelton JL. Investigative analysis of neonaticide: an exploratory study. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(4):522-535.

13. Putkonen H, Weizmann-Henelius G, Collander J, et al. Neonaticides may be more preventable and heterogeneous than previously thought--neonaticides in Finland 1980-2000. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(1):15-23.

14. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder and mental illness in parents: implications for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):587-588.

15. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126(3):325-334.

16. Friedman SH. Searching for the whole truth: considering culture and gender in forensic psychiatric practice. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2023;51(1):23-34.

17. Friedman SH, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: an examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(6):1466-1471.

18. Ash P. Fatal maltreatment and child abuse turned to murder. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. Group for the Advancement Psychiatry; 2018.

19. Friedman SH, Appel JM. Murder in the family: intimate partner homicide in the elderly. Psychiatric News. 2018. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.12a21

20. Friedman SH, McEwan MV. Treated mental illness and the risk of child abuse perpetration. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):211-216.

21. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

22. Hatters Friedman S, Beaman JW, Friedman JB. Fatality review and the role of the forensic psychiatrist. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2021;49(3):396-405.

23. Friedman SH, Prakash C, Nagle-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

24. Stanton J, Simpson AI, Wouldes T. A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(11):1451-1460.

25. Levitzky S, Cooper R. Infant colic syndrome—maternal fantasies of aggression and infanticide. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(7):395-400.

26. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(1-2):21-28.

27. Barr JA, Beck CT. Infanticide secrets: qualitative study on postpartum depression. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(12):1716-1717.e5.

28. Friedman SH, Sorrentino RM, Stankowski JE, et al. Psychiatrists’ knowledge about maternal filicidal thoughts. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):106-110.

29. Booth BD, Friedman SH, Curry S, et al. Obsessions of child murder: underrecognized manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(1):66-74.

30. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):30-36.

Emergency contraception for psychiatric patients

Ms. A, age 22, is a college student who presents for an initial psychiatric evaluation. Her body mass index (BMI) is 20 (normal range: 18.5 to 24.9), and her medical history is positive only for childhood asthma. She has been treated for major depressive disorder with venlafaxine by her previous psychiatrist. While this antidepressant has been effective for some symptoms, she has experienced adverse effects and is interested in a different medication. During the evaluation, Ms. A remarks that she had a “scare” last night when the condom broke while having sex with her boyfriend. She says that she is interested in having children at some point, but not at present; she is concerned that getting pregnant now would cause her depression to “spiral out of control.”

Unwanted or mistimed pregnancies account for 45% of all pregnancies.1 While there are ramifications for any unintended pregnancy, the risks for patients with mental illness are greater and include potential adverse effects on the neonate from both psychiatric disease and psychiatric medication use, worse obstetrical outcomes for patients with untreated mental illness, and worsening of psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk in the peripartum period.2 These risks become even more pronounced when psychiatric medications are reflexively discontinued or reduced in pregnancy, which is commonly done contrary to best practice recommendations. In the United States, the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization has erased federal protections for abortion previously conferred by Roe v Wade. As a result, as of early October 2022, abortion had been made illegal in 11 states, and was likely to be banned in many others, most commonly in states where there is limited support for either parents or children. Thus, preventing unplanned pregnancies should be a treatment consideration for all medical disciplines.3

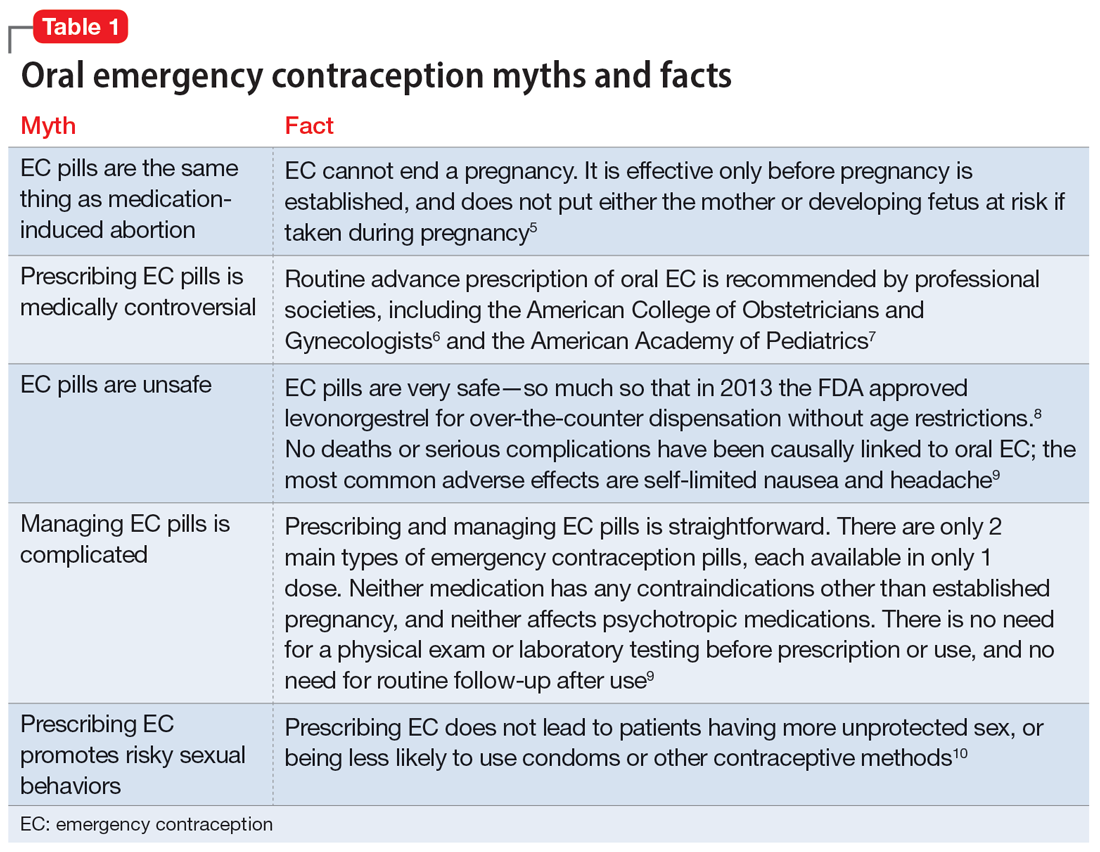

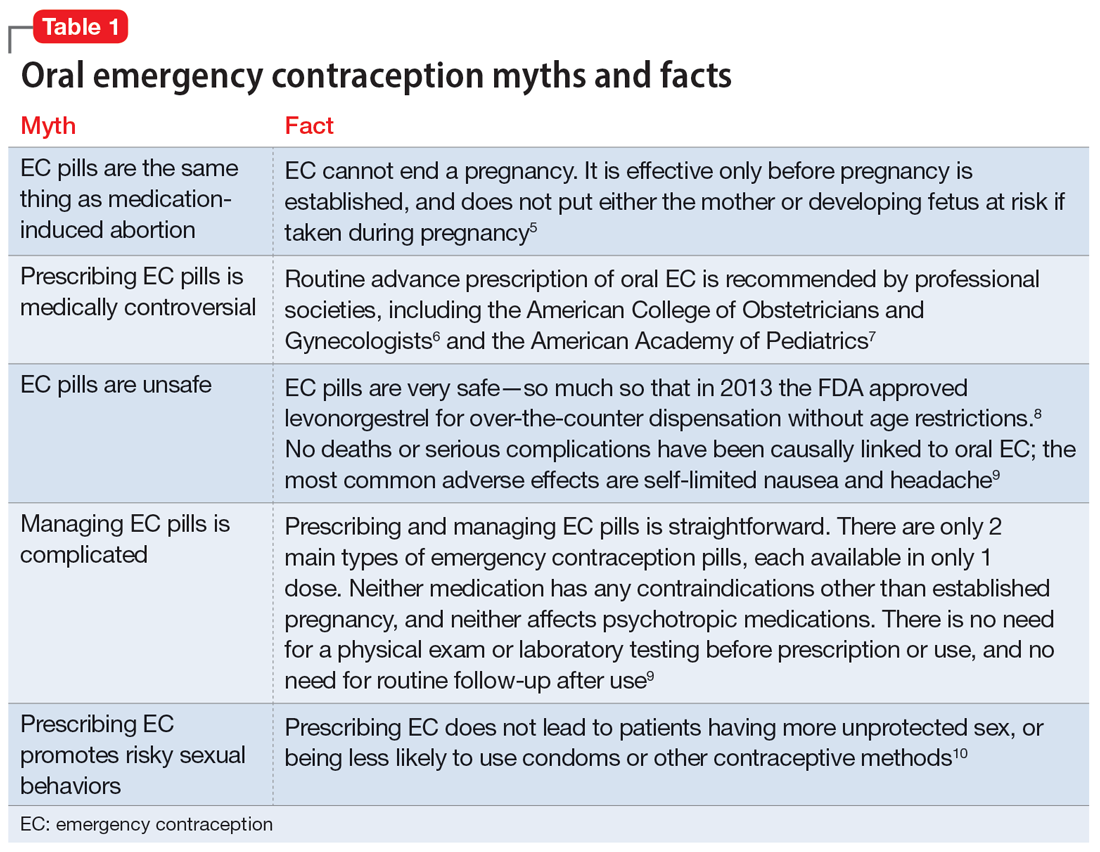

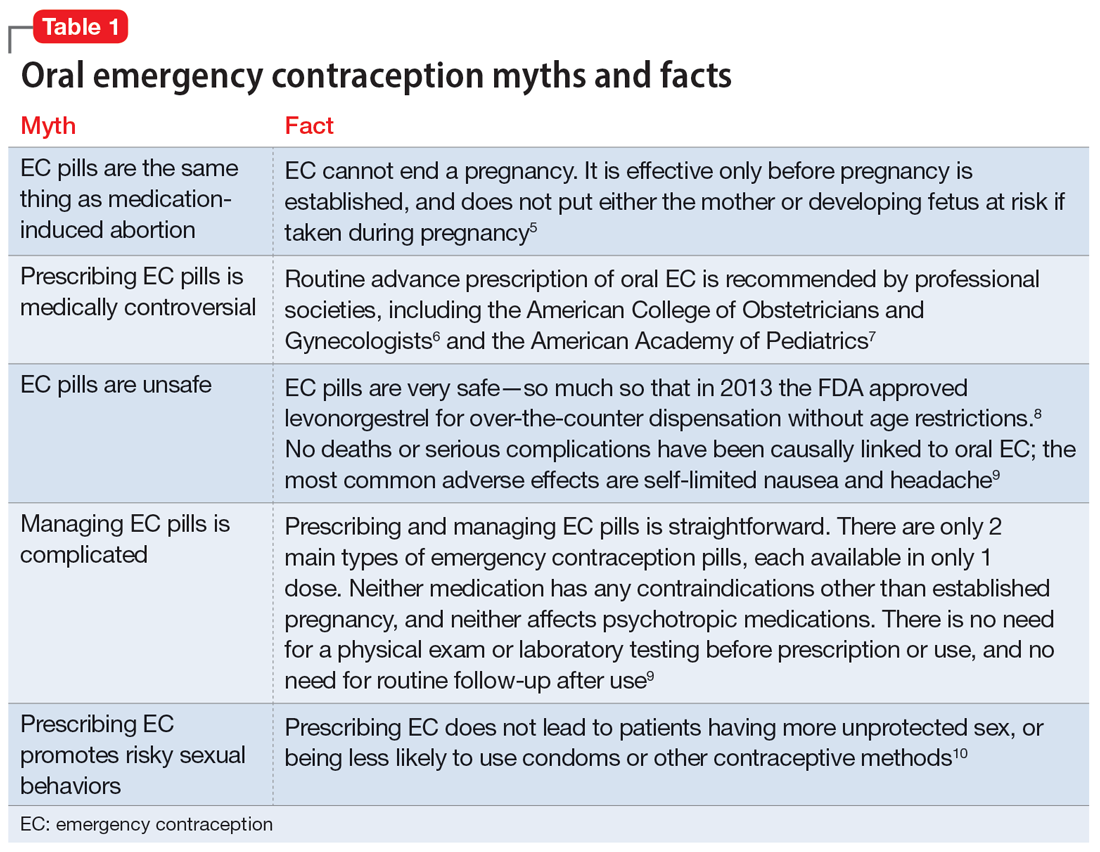

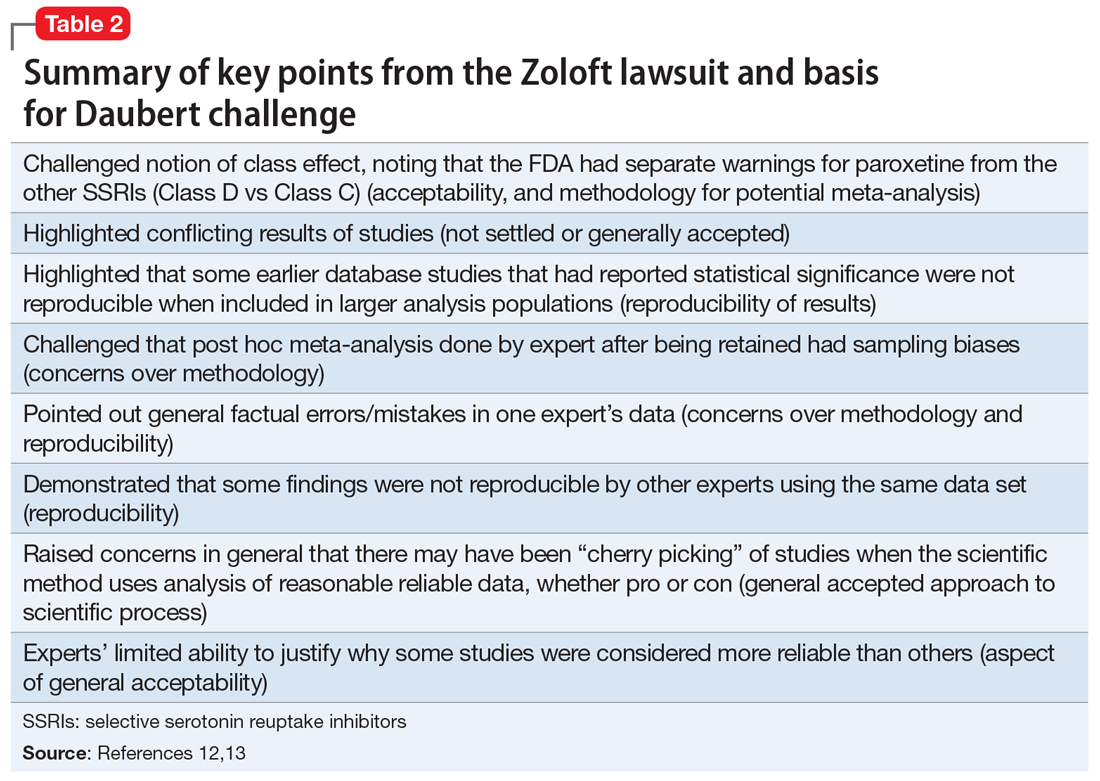

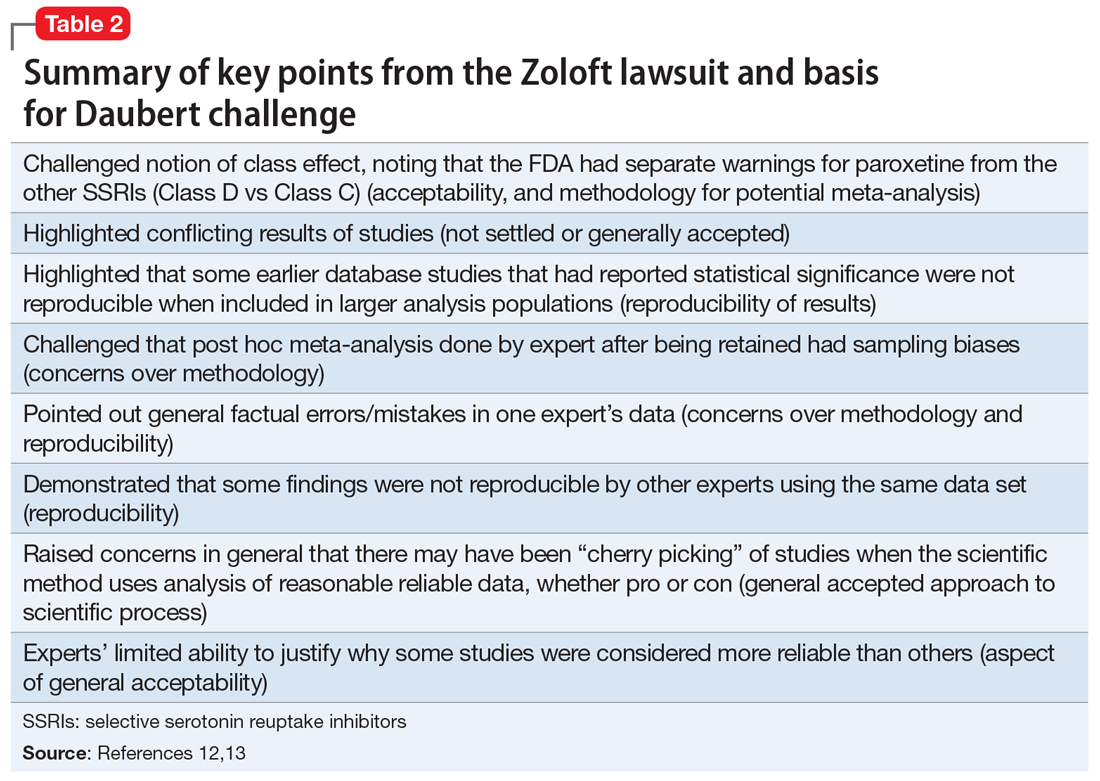

Psychiatrists may hesitate to prescribe emergency contraception (EC) due to fears it falls outside the scope of their practice. However, psychiatry has already moved towards prescribing nonpsychiatric medications when doing so clearly benefits the patient. One example is prescribing metformin to address metabolic syndrome related to the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Emergency contraceptives have strong safety profiles and are easy to prescribe. Unfortunately, there are many barriers to increasing access to emergency contraceptives for psychiatric patients.4 These include the erroneous belief that laboratory and physical exams are needed before starting EC, cost and/or limited stock of emergency contraceptives at pharmacies, and general confusion regarding what constitutes EC vs an oral abortive (Table 15-10). Psychiatrists are particularly well-positioned to support the reproductive autonomy and well-being of patients who struggle to engage with other clinicians. This article aims to help psychiatrists better understand EC so they can comfortably prescribe it before their patients need it.

What is emergency contraception?

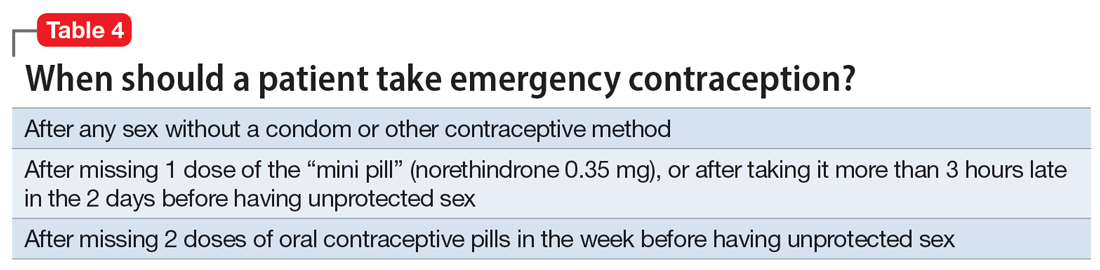

EC is medications or devices that patients can use after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy. They do not impede the development of an established pregnancy and thus are not abortifacients. EC is not recommended as a primary means of contraception,9 but it can be extremely valuable to reduce pregnancy risk after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failures such as broken condoms or missed doses of birth control pills. EC can prevent ≥95% of pregnancies when taken within 5 days of at-risk intercourse.11

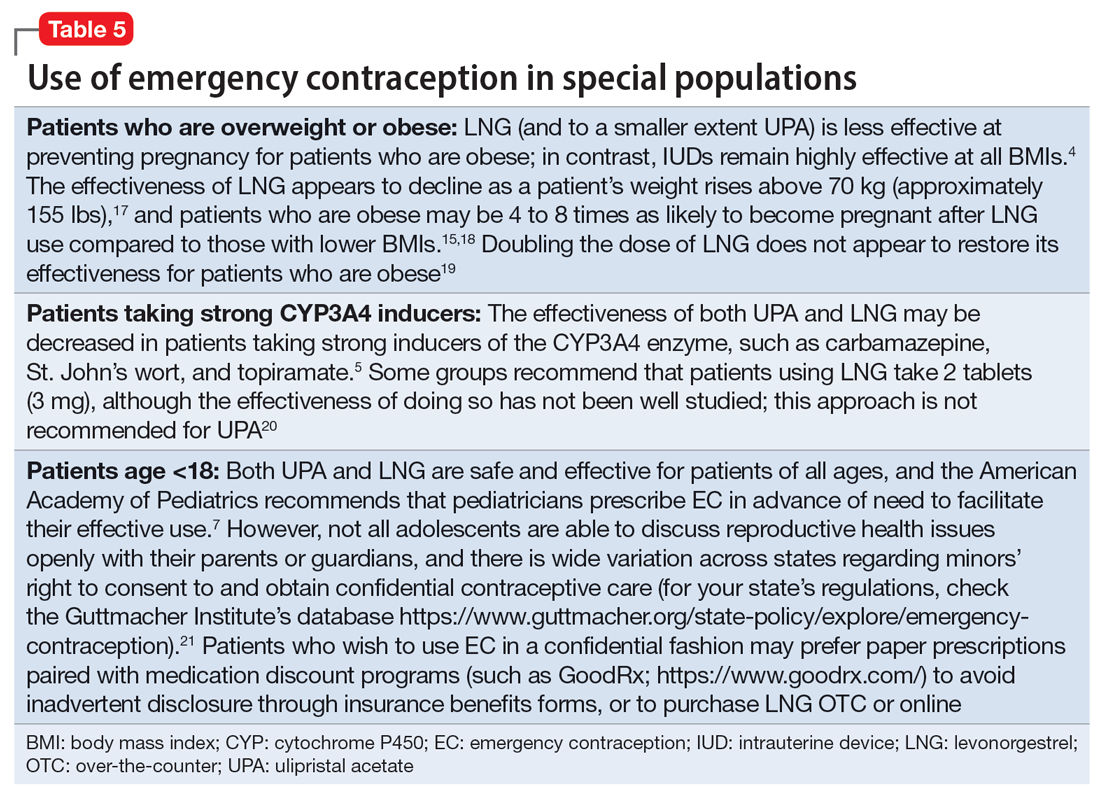

Methods of EC fall into 2 categories: oral medications (sometimes referred to as “morning after pills”) and intrauterine devices (IUDs). IUDs are the most effective means of EC, especially for patients with higher BMIs or who may be taking medications such as cytochrome P450 (CYP)3A4 inducers that could interfere with the effectiveness of oral methods. IUDs also have the advantage of providing highly effective ongoing contraception.6 However, IUDs require in-office placement by a trained clinician, and patients may experience difficulty obtaining placement within 5 days of unprotected sex. Therefore, oral medication is the most common form of EC.

Oral EC is safe and effective, and professional societies (including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 and the American Academy of Pediatrics7) recommend routinely prescribing oral EC for patients in advance of need. Advance prescribing eliminates barriers to accessing EC, increases the use of EC, and does not encourage risky sexual behaviors.10

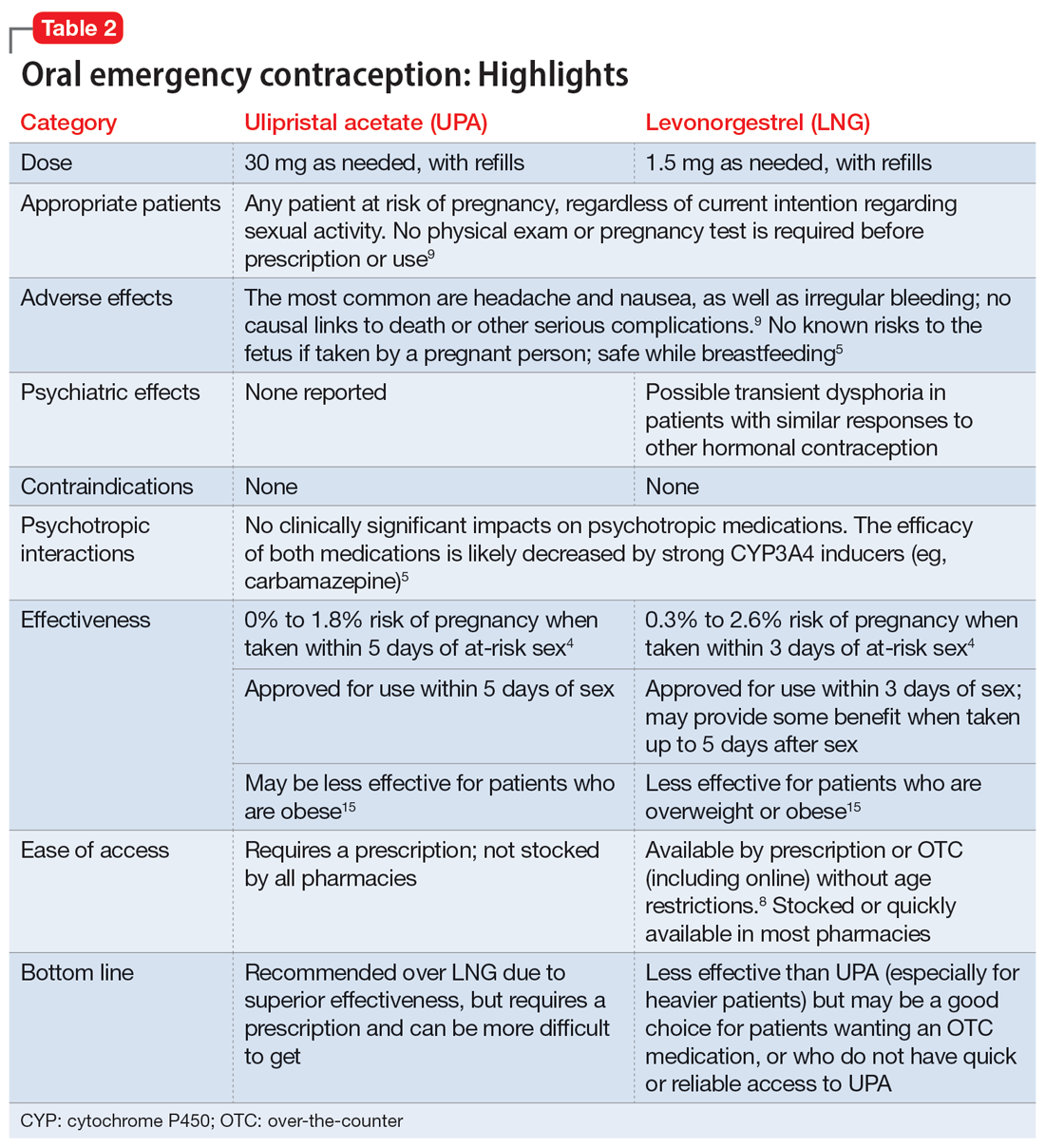

Overview of oral emergency contraception

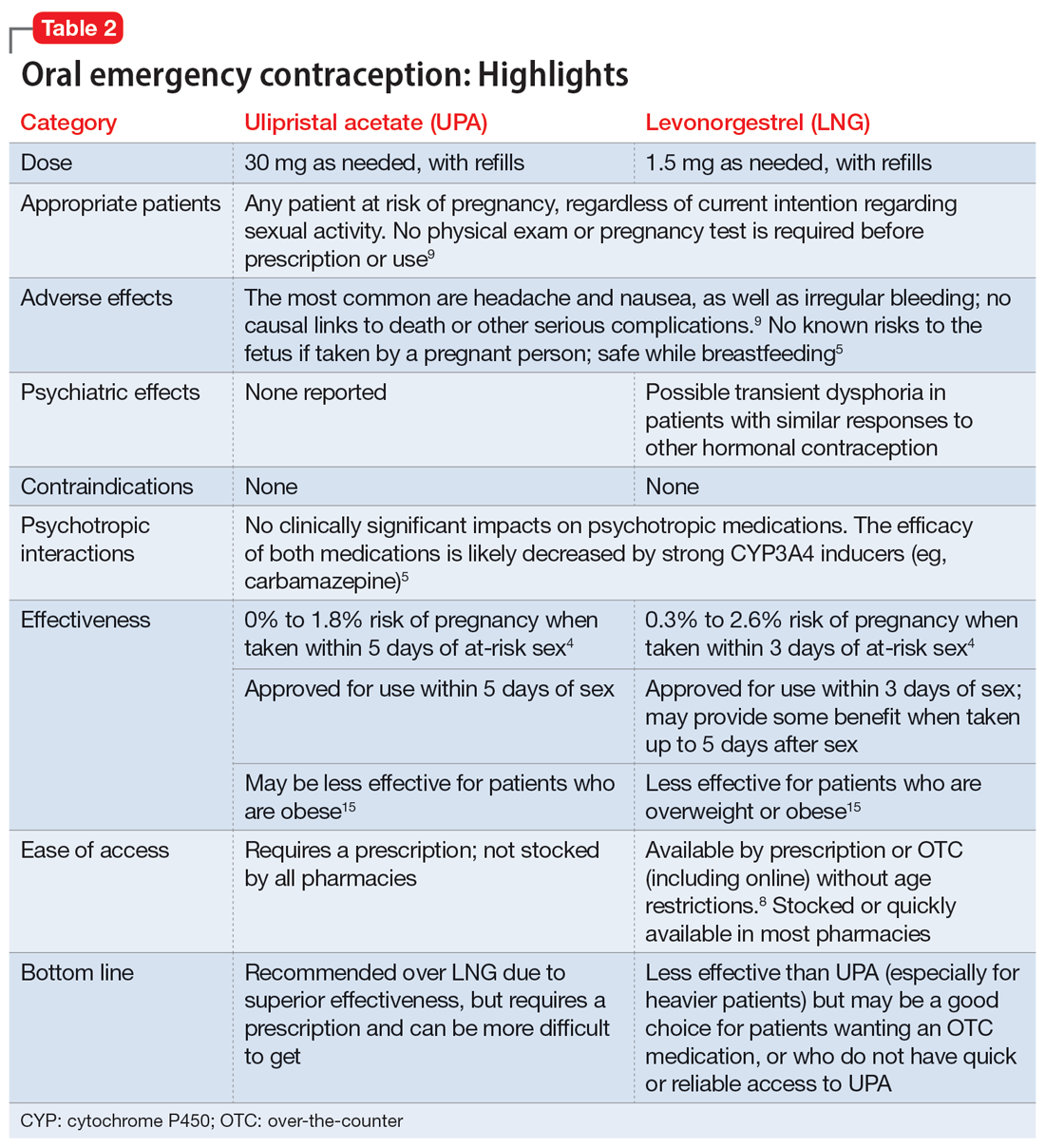

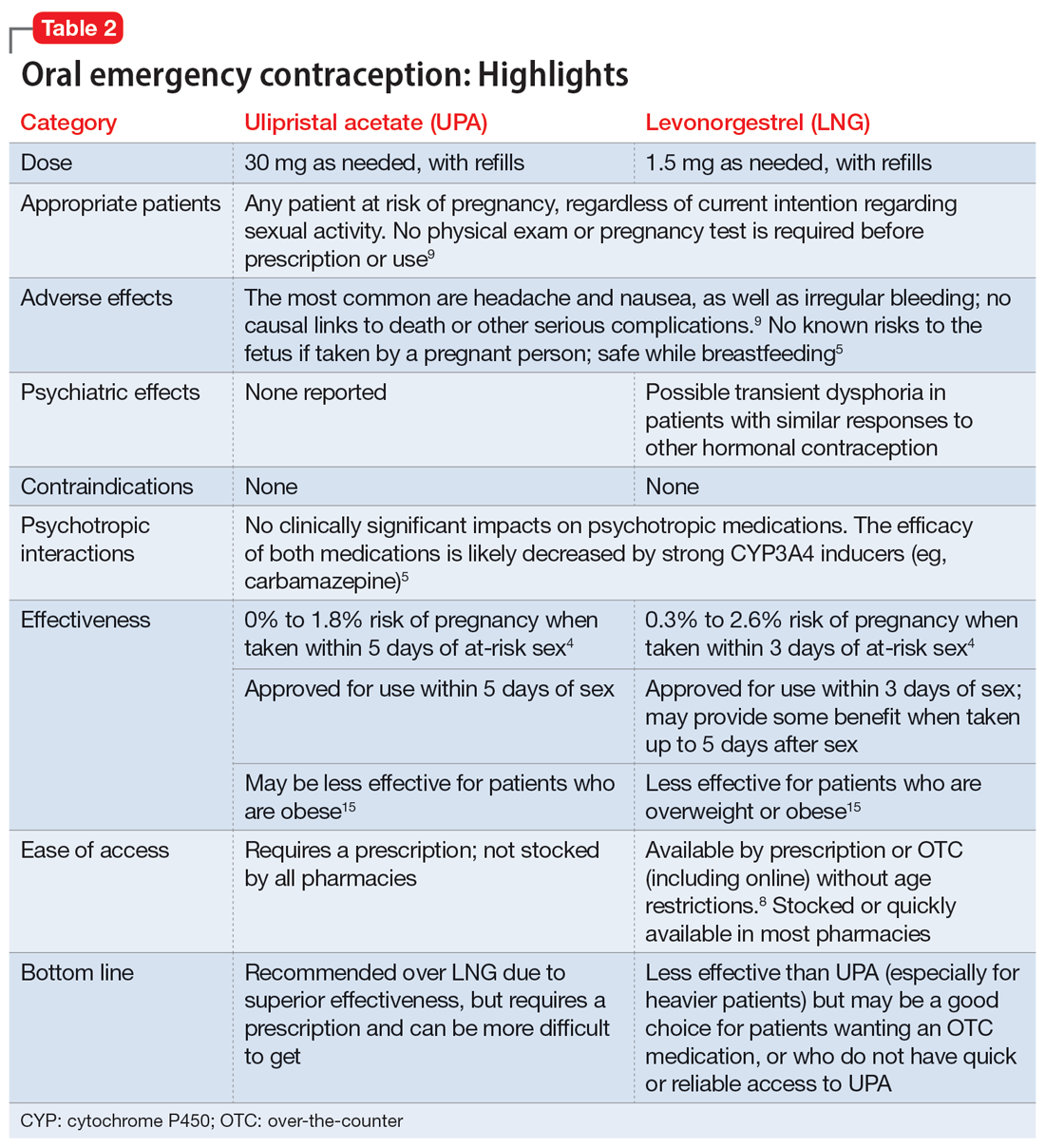

Two medications are FDA-approved for use as oral EC: ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Both are available in generic and branded versions. While many common birth control pills can also be safely used off-label as emergency contraception (an approach known as the Yuzpe method), they are less effective, not as well-tolerated, and require knowledge of the specific type of pill the patient has available.9 Oral EC appears to work primarily through delay or inhibition of ovulation, and is unlikely to prevent implantation of a fertilized egg.9

Continue to: Ulipristal acetate

Ulipristal acetate (UPA) is an oral progesterone receptor agonist-antagonist taken as a single 30 mg dose up to 5 days after unprotected sex. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by UPA use range from 0% to 1.8%.4 Many pharmacies stock UPA, and others (especially chain pharmacies) report being able to order and fill it within 24 hours.12

Levonorgestrel (LNG) is an oral progestin that is available by prescription and has also been approved for over-the-counter sale to patients of all ages and sexes (without the need to show identification) since 2013.8 It is administered as a single 1.5 mg dose taken as soon as possible up to 3 days after unprotected sex, although it may continue to provide benefits when taken within 5 days. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by LNG use range from 0.3% to 2.6%, with much higher odds among women who are obese.4 LNG is available both by prescription or over-the-counter,13 although it is often kept in a locked cabinet or behind the counter, and staff are often misinformed regarding the lack of age restrictions for sale without a prescription.14

Safety and adverse effects. According to the CDC, there are no conditions for which the risks outweigh the advantages of use of either UPA or LNG,5 and patients for whom hormonal birth control is otherwise contraindicated can still use them safely. If a pregnancy has already occurred, taking EC will not harm the developing fetus; it is also safe to use when breastfeeding.5 Both medications are generally well-tolerated—neither has been causally linked to deaths or serious complications,5 and the most common adverse effects are headache (approximately 19%) and nausea (approximately 12%), in addition to irregular bleeding, fatigue, dizziness, and abdominal pain.15 Oral EC may be used more than once, even within the same menstrual cycle. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be encouraged to discuss more efficacious contraceptive options with their primary physician or gynecologist.

Will oral EC affect psychiatric treatment?

Oral EC is unlikely to have a meaningful effect on psychiatric symptoms or management, particularly when compared to the significant impacts of unintended pregnancies. Neither medication is known to have any clinically significant impacts on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of psychotropic medications, although the effectiveness of both medications can be impaired by CYP3A4 inducers such as carbamazepine.5 In addition, while research has not specifically examined the impact of EC on psychiatric symptoms, the broader literature on hormonal contraception indicates that most patients with psychiatric disorders generally report similar or lower rates of mood symptoms associated with their use.16 Some women treated with hormonal contraceptives do develop dysphoric mood,16 but any such effects resulting from LNG would likely be transient. Mood disruptions or other psychiatric symptoms have not been associated with UPA use.

How to prescribe oral emergency contraception

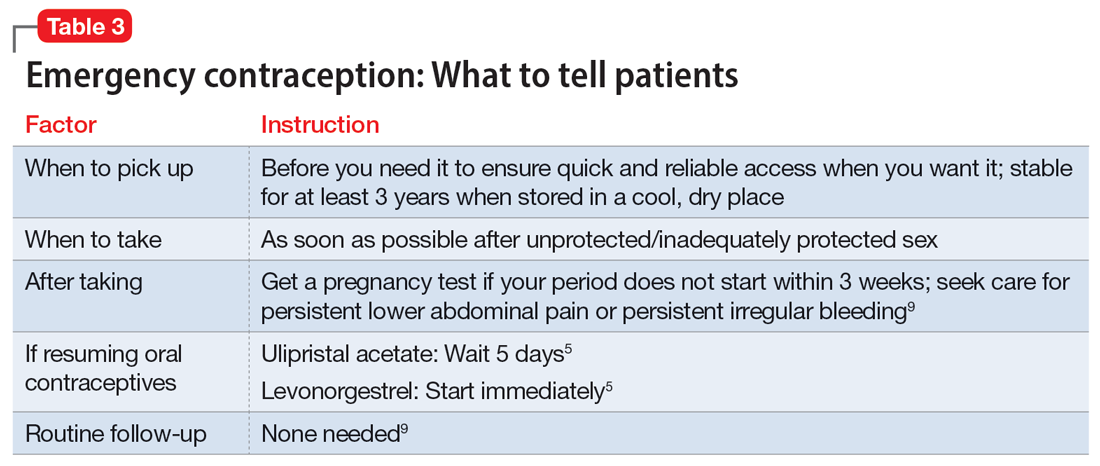

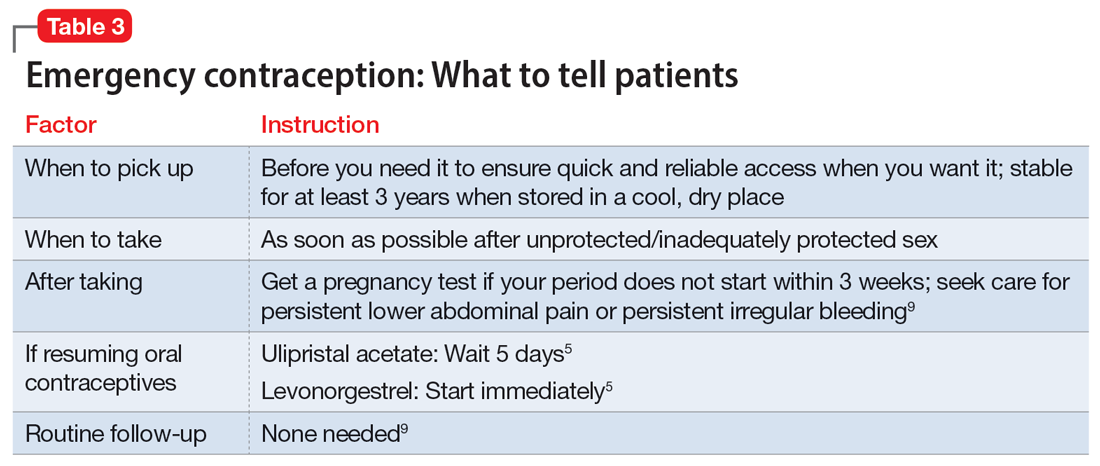

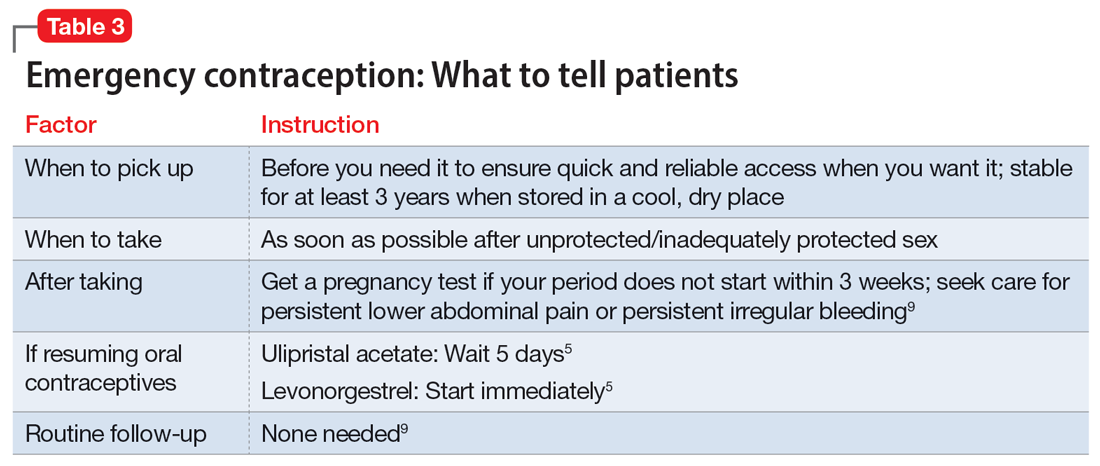

Who and when. Women of reproductive age should be counseled about EC as part of anticipatory guidance, regardless of their current intentions for sexual behaviors. Patients do not need a physical examination or pregnancy test before being prescribed or using oral EC.9 Much like how intranasal naloxone is prescribed, prescriptions should be provided in advance of need, with multiple refills to facilitate ready access when needed.

Continue to: Which to prescribe

Which to prescribe. UPA is more effective in preventing pregnancy than LNG at all time points up to 120 hours after sex, including for women who are overweight or obese.15 As such, it is recommended as the first-line choice. However, because LNG is available without prescription and is more readily available (including via online order), it may be a good choice for patients who need rapid EC or who prefer a medication that does not require a prescription (Table 24,5,8,9,15).

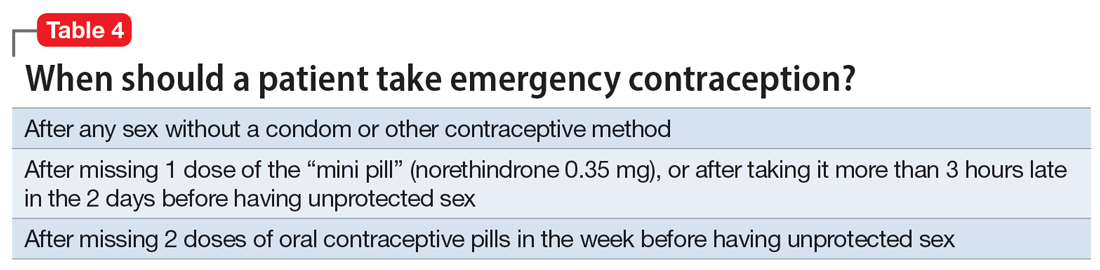

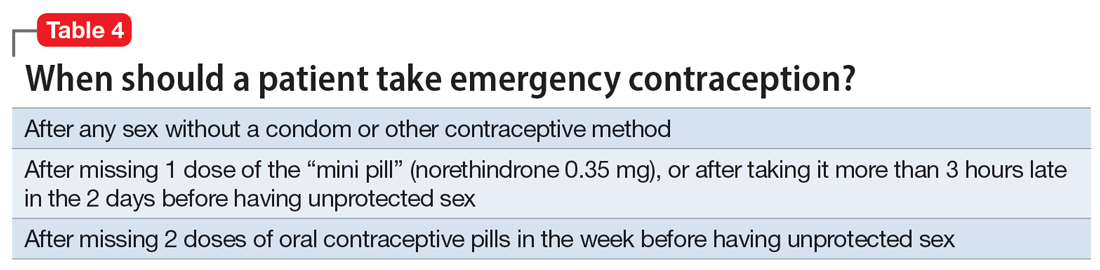

What to tell patients. Patients should be instructed to fill their prescription before they expect to use it, to ensure ready availability when desired (Table 35,9). Oral EC is shelf stable for at least 3 years when stored in a cool, dry environment. Patients should take the medication as soon as possible following at-risk sexual intercourse (Table 4). Tell them that if they vomit within 3 hours of taking the medication, they should take a second dose. Remind patients that EC does not protect against sexually transmitted infections, or from sex that occurs after the medication is taken (in fact, they can increase the possibility of pregnancy later in that menstrual cycle due to delayed ovulation).9 Counsel patients to abstain from sex or to use barrier contraception for 7 days after use. Those who take birth control pills can resume use immediately after using LNG; they should wait 5 days after taking UPA.

No routine follow-up is needed after taking UPA or LNG. However, patients should get a pregnancy test if their period does not start within 3 weeks, and should seek medical evaluation if they experience significant lower abdominal pain or persistent irregular bleeding in order to rule out pregnancy-related complications. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be recommended to pursue routine contraceptive care.

Billing. Counseling your patients about contraception can increase the reimbursement you receive by adding to the complexity of the encounter (regardless of whether you prescribe a medication) through use of the ICD-10 code Z30.0.

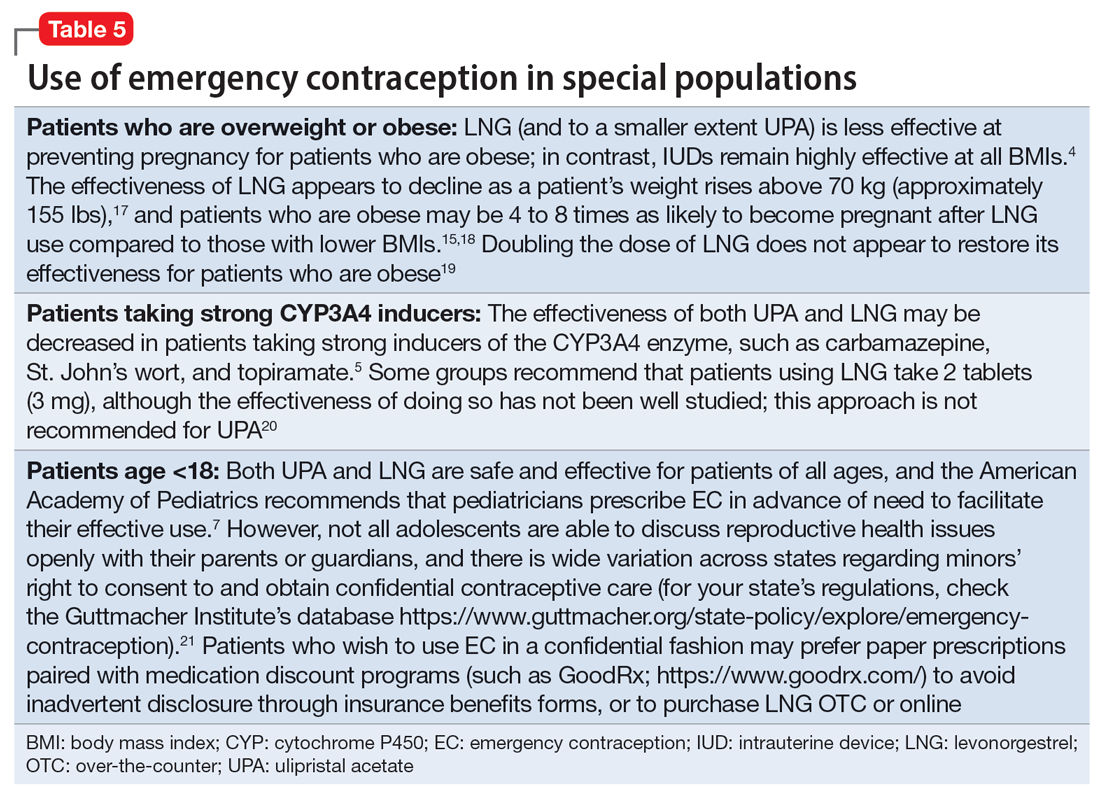

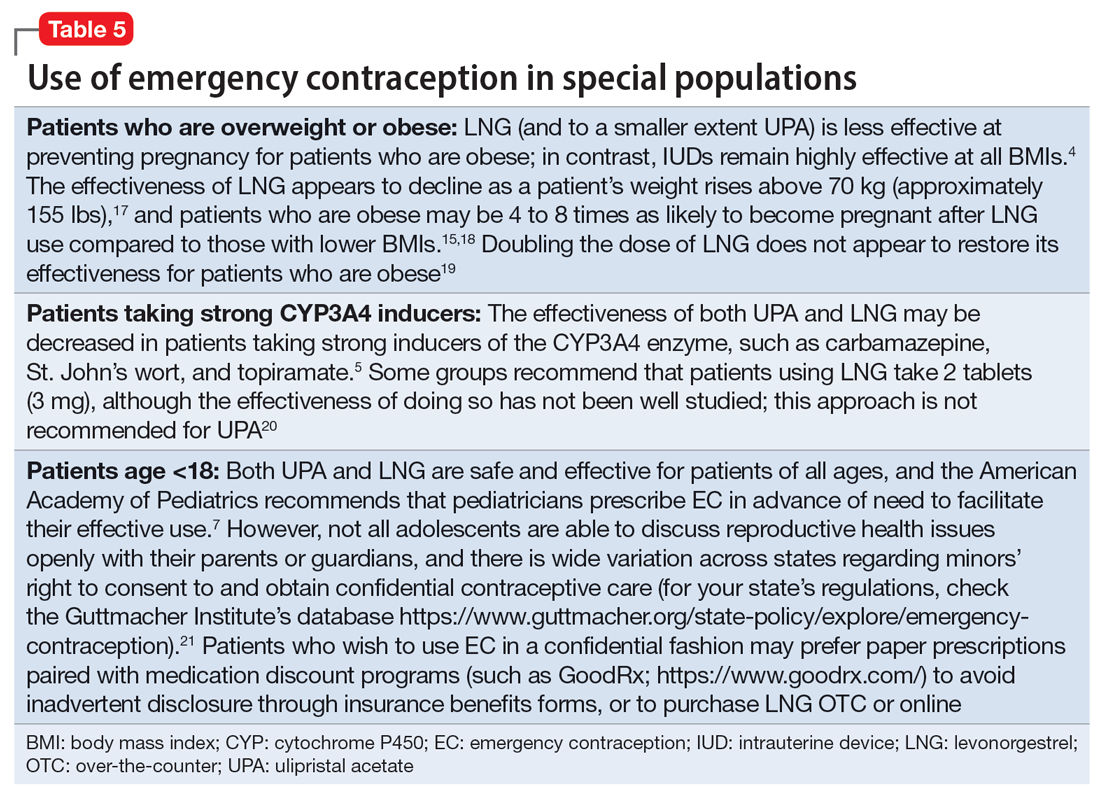

Emergency contraception for special populations

Some patients face additional challenges to effective EC that should be considered when counseling and prescribing. Table 54,5,7,15,17-21 discusses the use of EC in these special populations. Of particular importance for psychiatrists, LNG is less effective at preventing undesired pregnancy among patients who are overweight or obese,15,17,18 and strong CYP3A4-inducing agents may decrease the effectiveness of both LNG and UPA.5 Keep in mind, however, that the advantages of using either UPA or LNG outweigh the risks for all populations.5 Patients must be aware of appropriate information in order to make informed decisions, but should not be discouraged from using EC.

Continue to: Other groups of patients...

Other groups of patients may face barriers due to some clinicians’ hesitancy regarding their ability to consent to reproductive care. Most patients with psychiatric illnesses have decision-making capacity regarding reproductive issues.22 Although EC is supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics,7 patients age <18 have varying rights to consent across states,21 and merit special consideration.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. A does not wish to get pregnant at this time, and expresses fears that her recent contraceptive failure could lead to an unintended pregnancy. In addition to her psychiatric treatment, her psychiatrist should discuss EC options with her. She has a healthy BMI and had inadequately protected sex <1 day ago, so her clinician may prescribe LNG (to ensure rapid access for immediate use) in addition to UPA for her to have available in case of future “scares.” The psychiatrist should consider pharmacologic treatment with an antidepressant with a relatively safe reproductive record (eg, sertraline).23 This is considered preventive ethics, since Ms. A is of reproductive age, even if she is not presently planning to get pregnant, due to the aforementioned high rate of unplanned pregnancy.23,24 It is also important for the psychiatrist to continue the dialogue in future sessions about preventing unintended pregnancy. Since Ms. A has benefited from a psychotropic medication when not pregnant, it will be important to discuss with her the risks and benefits of medication should she plan a pregnancy.

Bottom Line

Patients with mental illnesses are at increased risk of adverse outcomes resulting from unintended pregnancies. Clinicians should counsel patients about emergency contraception (EC) as a part of routine psychiatric care, and should prescribe oral EC in advance of patient need to facilitate effective use.

Related Resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on Emergency Contraception. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/ articles/2015/09/emergency-contraception

- State policies on emergency contraception. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/emergency-contraception

- State policies on minors’ access to contraceptive services. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

- Patient-oriented contraceptive education materials (in English and Spanish). https://shop.powertodecide.org/ptd-category/educational-materials

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Levonorgestrel • Plan B One-Step, Fallback

Metformin • Glucophage

Naloxone • Narcan

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topamax

Ulipristal acetate • Ella

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Grossman D. Expanding access to short-acting hormonal contraceptive methods in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1209-1210.

2. Gur TL, Kim DR, Epperson CN. Central nervous system effects of prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: sensing the signal through the noise. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;227:567-582.

3. Ross N, Landess J, Kaempf A, et al. Pregnancy termination: what psychiatrists need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21:8-9.

4. Haeger KO, Lamme J, Cleland K. State of emergency contraception in the US, 2018. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:20.

5. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-3.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No 707: Access to emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e48-e52.

7. Upadhya KK, Breuner CC, Alderman EM, et al. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20193149.

8. Rowan A. Obama administration yields to the courts and the evidence, allows emergency contraception to be sold without restrictions. Guttmacher Institute. Published June 25, 2013. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2013/06/obama-administration-yields-courts-and-evidence-allows-emergency-contraception-be-sold#

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 152: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e1-e11.

10. Rodriguez MI, Curtis KM, Gaffield ML, et al. Advance supply of emergency contraception: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:590-601.

11. World Health Organization. Emergency contraception. Published November 9, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/emergency-contraception

12. Shigesato M, Elia J, Tschann M, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in major cities throughout the United States. Contraception. 2018;97:264-269.

13. Wilkinson TA, Clark P, Rafie S, et al. Access to emergency contraception after removal of age restrictions. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20164262.

14. Cleland K, Bass J, Doci F, et al. Access to emergency contraception in the over-the-counter era. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26:622-627.

15. Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555-562.

16. McCloskey LR, Wisner KL, Cattan MK, et al. Contraception for women with psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:247-255.

17. Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91:97-104.

18. Festin MP, Peregoudov A, Seuc A, et al. Effect of BMI and body weight on pregnancy rates with LNG as emergency contraception: analysis of four WHO HRP studies. Contraception. 2017;95:50-54.

19. Edelman AB, Hennebold JD, Bond K, et al. Double dosing levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception for individuals with obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(1):48-54.

20. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. FSRH clinical guideline: Emergency contraception. Published March 2017. Amended December 2020. Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.fsrh.org/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-emergency-contraception-march-2017/

21. Guttmacher Institute. Minors’ access to contraceptive services. Guttmacher Institute. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

22. Ross NE, Webster TG, Tastenhoye CA, et al. Reproductive decision-making capacity in women with psychiatric illness: a systematic review. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2022;63:61-70.

23. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20:30-36.

24. Friedman SH. The ethics of treating depression in pregnancy. J Primary Healthcare. 2015;7:81-83.

Ms. A, age 22, is a college student who presents for an initial psychiatric evaluation. Her body mass index (BMI) is 20 (normal range: 18.5 to 24.9), and her medical history is positive only for childhood asthma. She has been treated for major depressive disorder with venlafaxine by her previous psychiatrist. While this antidepressant has been effective for some symptoms, she has experienced adverse effects and is interested in a different medication. During the evaluation, Ms. A remarks that she had a “scare” last night when the condom broke while having sex with her boyfriend. She says that she is interested in having children at some point, but not at present; she is concerned that getting pregnant now would cause her depression to “spiral out of control.”