User login

Article Type

Changed

Display Headline

Cognitive Screening Tools

As our elderly population continues to grow, the issues of screening for cognitive impairment and early detection of dementia are becoming increasingly important. Cognitive impairment, particularly in individuals who live alone, contributes to loss of independence, decreased quality of life, and increased health care costs.1 There are serious and costly implications of unrecognized dementia, including delayed treatment of reversible conditions, medication noncompliance for comorbid conditions, inaccurate and unreliable reporting by patients, safety concerns, potential catastrophes, and increased risk for victimization.

Clinicians in all settings can expect to care for increasing numbers of older adults—many with various degrees of cognitive difficulties. Such problems, especially if undetected, can significantly impact the ongoing management of both acute and chronic medical problems. In primary care settings, it has been reported, between 50% and 65% of patients found to have cognitive deficits meeting the criteria for dementia did not have a diagnosis of dementia noted in their medical record.2

The annual wellness examination provided for under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act3 (PPACA) for Medicare beneficiaries is required to include an assessment of cognitive function,4 but the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) have not, to date, recommended any specific screening instrument; examiners are expected to base their assessment on observation and reports from the patient and other informants.5

WHY DO TESTING?

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

It is well documented that dementia remains underrecognized and may indeed be the “silent epidemic” of this century.8 Current estimates are that the incidence of new cases of Alzheimer’s disease will double by 2050.9 Additionally, improvement in stroke survival rates means that there will likely be increases in vascular and poststroke dementia, as one-third of stroke patients have been found to develop a progressive dementia.10

The early detection of cognitive change offers benefits for both patients and providers. If early detection leads to a diagnosis of dementia (regardless of etiology), this can provide an explanation to patients and families regarding recent changes in function, mood, and behavior. A diagnosis of progressive dementia (eg, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia) provides an opportunity for early medication management, review and simplification of ongoing chronic disease management, and prevention of problems commonly associated with mismanagement. More importantly, early diagnosis of dementia enables patients to be more involved in planning for their own future care needs, such as execution of advance directives.

Cognitive screening may also help in identification of the at-risk driver or those who should undergo further assessment for fitness to drive.7

WHO SHOULD BE SCREENED?

There is no clear consensus on who should undergo cognitive screening or how frequently it should be carried out. Screening should be targeted at individuals who are at greatest risk for either progressive dementia or delirium. Advancing age is a known risk factor for dementia, but there is no agreement on a specific age at which to initiate cognitive screening. In patients older than 80, there is a 25% to 50% prevalence of dementia,1,11,12 thus suggesting that cognitive screening should be initiated before this age. Furthermore, clinicians who provide medical care for patients of advanced age must be increasingly attentive to the possible presence of cognitive decline.

There is no clear consensus on who should undergo cognitive screening or how frequently it should be carried out. Screening should be targeted at individuals who are at greatest risk for either progressive dementia or delirium. Advancing age is a known risk factor for dementia, but there is no agreement on a specific age at which to initiate cognitive screening. In patients older than 80, there is a 25% to 50% prevalence of dementia,1,11,12 thus suggesting that cognitive screening should be initiated before this age. Furthermore, clinicians who provide medical care for patients of advanced age must be increasingly attentive to the possible presence of cognitive decline.

Individuals with subjective memory complaints and those with a history of depression have been identified as being at high risk for dementia.13,14 The American Academy of Neurology recommends cognitive screening in any patient in whom cognitive impairment is suspected.15 This usually occurs when a family member or other individual close to the patient (eg, employer, friend) becomes concerned about changes in the patient’s thinking, behavior, or function. Additionally, older individuals who have recently undergone surgery or been hospitalized are a population at high risk for acute cognitive changes and should be considered candidates for mental status screening.16-20

Another population for whom cognitive screening may be appropriate is patients with certain medical conditions known to be associated with dementia, as well as any older person with unexplained functional decline. Examples of conditions associated with cognitive decline include Parkinson’s disease, a history of stroke, and diabetes mellitus.21-23

Most patients with memory difficulties and other cognitive problems do not report these complaints to their medical provider, and it is unrealistic to expect them to do so. Often it is a family member or a coworker who becomes aware of a problem and voices these concerns to the provider; however, the provider should not rely on this to ensure early detection.

Clinicians must be pro-active and maintain a high index of suspicion for cognitive difficulties, especially when treating adults older than 70 or 75. Becoming familiar with a variety of tools and using one or more regularly to determine whether an individual does or does not have cognitive changes that might warrant further assessment should be a routine part of care.

WHICH TEST TO USE?

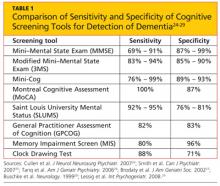

There is no single, ideal cognitive screening tool that can be recommended for use in every clinical setting. However, the ideal tool would have high sensitivity (ie, the proportion of those with impairment correctly classified as impaired), high specificity (the proportion of those who are unimpaired correctly identified as not having cognitive problems; see Table 1,24-29 below), and a high positive predictive value (proportion identified by screening as impaired who really have cognitive impairment). Additionally, such a tool should be easy to administer and score, and should take a minimum amount of time to conduct in our time-pressured clinical environment.

There is no single, ideal cognitive screening tool that can be recommended for use in every clinical setting. However, the ideal tool would have high sensitivity (ie, the proportion of those with impairment correctly classified as impaired), high specificity (the proportion of those who are unimpaired correctly identified as not having cognitive problems; see Table 1,24-29 below), and a high positive predictive value (proportion identified by screening as impaired who really have cognitive impairment). Additionally, such a tool should be easy to administer and score, and should take a minimum amount of time to conduct in our time-pressured clinical environment.

Many of the currently available cognitive screening tests overemphasize memory to the neglect of other areas of cognitive function, such as executive function, language, and praxis, which can be impacted in patients with various conditions.24 One review of cognitive screening tests suggests that a comprehensive screening instrument should include six core neuropsychologic domains that are most commonly affected in the early stages of different dementias:

• Executive function

• Abstract reasoning

• Attention/working memory

• New verbal learning and recall

• Expressive language

• Visuospatial construction.24

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT SCREENING TESTS

Cognitive screening does involve some risk, and every tool has known limitations. A significant barrier can be the administration time required, possibly ranging from five to 20 minutes. There is a potential for false-positive results, and there can be distress and stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, for both patients and families.

Cognitive screening does involve some risk, and every tool has known limitations. A significant barrier can be the administration time required, possibly ranging from five to 20 minutes. There is a potential for false-positive results, and there can be distress and stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, for both patients and families.

The majority of cognitive screening tests were developed and validated using cohorts of English-speaking patients. When used in other populations, such as those with English as a second (or third) language, or when used in translation, the results may not be valid. Similarly, many tests have an inherent educational bias, presuming attainment of an eighth-grade level or higher—again calling results into question when the test is conducted in people with less formal education. Further, most of the currently available tools are insensitive to small changes, as they were designed for screening, not to detect changes in a patient over time.

Screening tests may have a ceiling effect, that is, they may be insensitive to changes among patients with high intelligence or high levels of education premorbidity. Some tests may also have a floor effect, lacking the ability to assess for change in patients below a certain level of education or intelligence. The summary scores of these tests have cut-offs for normal and may allow broad-range classification of levels of impairment as mild, moderate, or severe; this is not very useful in distinguishing different patterns of cognitive loss.

COGNITIVE SCREENING TOOLS

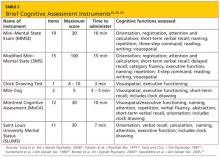

A variety of tools are available for bedside/clinical assessment of cognition (see Table 226,30-34 below). Their administration can be learned without difficulty, and they can be conducted with relative ease to provide insight into a patient’s cognitive abilities and deficits.

A variety of tools are available for bedside/clinical assessment of cognition (see Table 226,30-34 below). Their administration can be learned without difficulty, and they can be conducted with relative ease to provide insight into a patient’s cognitive abilities and deficits.

Mini–Mental State Exam

The most commonly used cognitive screening tool is the Folstein Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE).30 With administration taking about 15 minutes, the MMSE includes assessment of attention, orientation, registration, recall/short-term memory, language, and visuospatial construction. Clinicians will find this tool most useful in assessing the individual with suspected early dementia and to follow progression through the early and middle stages of cognitive decline in those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders.

The most commonly used cognitive screening tool is the Folstein Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE).30 With administration taking about 15 minutes, the MMSE includes assessment of attention, orientation, registration, recall/short-term memory, language, and visuospatial construction. Clinicians will find this tool most useful in assessing the individual with suspected early dementia and to follow progression through the early and middle stages of cognitive decline in those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders.

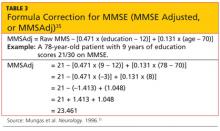

The maximum score is 30 points, with impairment suspected in subjects whose score is 25 or lower. The MMSE is highly dependent on verbal memory, and it does not include any tests of executive function; performance can be influenced by education and cultural background. A formula has been developed that takes age and education into account, allowing for correction of the score35 (see Table 335). The MMSE is currently a proprietary document requiring payment for its use.

The Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS)31 expands upon the MMSE with the addition of items that address remote memory, delayed recall, list generation, and judgment and reasoning. With a maximum score of 100 points, it allows for partially correct responses to be scored. For example, on verbal recall, cuing and choices are provided, with subsequent correct answers awarded partial points (ie, 1 or 2 points out of a 3-point maximum score per recall item). Cognitive impairment is defined by a score of 85 points or less.

The 3MS may be more sensitive in identification of early dementia than is the MMSE. The 3MS’s expanded item scoring may be helpful in differentiating between some of the clinical dementia subtypes, such as Alzheimer’s versus vascular dementia.36

Clock Drawing Test

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is perhaps the simplest test to administer.29,32 The patient is given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw a large circle, then to write numbers inside the circle so that it resembles a face of a clock. Once this is completed, the patient is instructed to “draw the hands on the clock to read ten past eleven.”

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is perhaps the simplest test to administer.29,32 The patient is given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw a large circle, then to write numbers inside the circle so that it resembles a face of a clock. Once this is completed, the patient is instructed to “draw the hands on the clock to read ten past eleven.”

There are multiple scoring systems for the CDT,29,32,37 with points given for accuracy of placement of the numbers and the size and position of the hands. Lower scores generally indicate greater impairment. The advantages of the CDT are that it is not very threatening, it is very sensitive to changes in early Alzheimer’s disease, and its administration requires little training.29 It has also been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety.38

The CDT is most appropriate for screening in busy practices and other settings (eg, health fairs) where further evaluation can be relied upon to identify any false-positive test results.

Mini-Cog Test

The Mini-Cog Test (with instructions available at http://geriatrics.uthscsa.edu/tools/MINICog.pdf) includes the clock-drawing task and a three-word recall, with a simple scoring algorithm.33 Ability to recall all three words, or to recall one or two words with normal results on the clock test, represents a negative screening result for dementia. Conversely, an inability to recall any of the three words, or ability to recall only one or two words with an abnormal clock test, is considered a positive screen for dementia. The Mini-Cog is a good tool for identification of early dementia, but not useful for following changes in individuals identified with cognitive impairment.

The Mini-Cog Test (with instructions available at http://geriatrics.uthscsa.edu/tools/MINICog.pdf) includes the clock-drawing task and a three-word recall, with a simple scoring algorithm.33 Ability to recall all three words, or to recall one or two words with normal results on the clock test, represents a negative screening result for dementia. Conversely, an inability to recall any of the three words, or ability to recall only one or two words with an abnormal clock test, is considered a positive screen for dementia. The Mini-Cog is a good tool for identification of early dementia, but not useful for following changes in individuals identified with cognitive impairment.

The Mini-Cog has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE, but it is much briefer and easier to administer. It is also less prone to language or ethnic bias, making it appropriate for patients with a wide variety of backgrounds and educational levels, and it translates easily for use in other languages.33,39

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was originally designed as a brief screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment.34 It is a single-page, 30-point test, available in multiple languages (with several versions in some languages) at www.mocatest.org. The MoCA includes assessment of short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation. A score of 25 or lower is considered subnormal.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was originally designed as a brief screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment.34 It is a single-page, 30-point test, available in multiple languages (with several versions in some languages) at www.mocatest.org. The MoCA includes assessment of short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation. A score of 25 or lower is considered subnormal.

By design, the MoCA is useful for detecting subtle deficits that may be missed in patients who are highly educated, who score within the normal range on MMSE (≥ 25), or who have prominent executive dysfunction. The test has been shown to have excellent sensitivity in identification of early/mild cognitive changes and high test-retest reliability, and it is considered an excellent screening tool for detection of cognitive impairment in a busy clinical setting.40

Saint Louis University Mental Status

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) has also been shown to have better sensitivity than the MMSE for early cognitive changes.26 This 11-item tool, with a maximum score of 30 points, includes assessment of seven cognitive domains: orientation, recall, attention, calculation, fluency, language, and visuospatial construction. The five-item delayed recall in the SLUMS has been shown to be an excellent discriminator of those with normal cognition versus mild cognitive change. It is available for general use with no fee; currently, it is widely used by the Veterans Administration system.41

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) has also been shown to have better sensitivity than the MMSE for early cognitive changes.26 This 11-item tool, with a maximum score of 30 points, includes assessment of seven cognitive domains: orientation, recall, attention, calculation, fluency, language, and visuospatial construction. The five-item delayed recall in the SLUMS has been shown to be an excellent discriminator of those with normal cognition versus mild cognitive change. It is available for general use with no fee; currently, it is widely used by the Veterans Administration system.41

General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition

The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)27 is a unique two-part tool that includes questions for the patient and for someone who knows the patient well (“informant”). The patient items include memory/recall, orientation, and visuospatial tasks. The six informant questions ask about recall, language, and functional abilities. The GPCOG has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE27; as its name indicates, it is designed and best suited for screening in a family medicine or general internal medicine practice.

The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)27 is a unique two-part tool that includes questions for the patient and for someone who knows the patient well (“informant”). The patient items include memory/recall, orientation, and visuospatial tasks. The six informant questions ask about recall, language, and functional abilities. The GPCOG has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE27; as its name indicates, it is designed and best suited for screening in a family medicine or general internal medicine practice.

Memory Impairment Screen

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)28 uses a four-item memory recall with simple scoring of 0 to 8, based on the formula: 2x [the number recalled spontaneously) + (the number recalled with cuing)]. It takes less than five minutes to administer, making it a useful tool to screen for suspected memory problems in a busy setting, such as an emergency room. However, the sole reliance on memory, without screening for any other areas of cognition (especially executive function or visuospatial copying), significantly limits the usefulness of the MIS as a general cognitive screening tool.

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)28 uses a four-item memory recall with simple scoring of 0 to 8, based on the formula: 2x [the number recalled spontaneously) + (the number recalled with cuing)]. It takes less than five minutes to administer, making it a useful tool to screen for suspected memory problems in a busy setting, such as an emergency room. However, the sole reliance on memory, without screening for any other areas of cognition (especially executive function or visuospatial copying), significantly limits the usefulness of the MIS as a general cognitive screening tool.

Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status

The cognitive screening instruments described thus far were all designed to be administered in person in a medical setting (office, clinic, or hospital). The 11-item Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)42 was developed as a brief (taking less than 10 minutes) standardized test of cognitive function, specifically suited for situations in which in-person screening is not possible (eg, for patients who are unable to appear in person for clinical follow-up).42-44 The modified TICS (TICS-M), which includes 13 items, has been shown to have less of a ceiling effect than the MMSE.45 It has also been shown to be a cost-effective screening tool for mild cognitive impairment.46

The cognitive screening instruments described thus far were all designed to be administered in person in a medical setting (office, clinic, or hospital). The 11-item Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)42 was developed as a brief (taking less than 10 minutes) standardized test of cognitive function, specifically suited for situations in which in-person screening is not possible (eg, for patients who are unable to appear in person for clinical follow-up).42-44 The modified TICS (TICS-M), which includes 13 items, has been shown to have less of a ceiling effect than the MMSE.45 It has also been shown to be a cost-effective screening tool for mild cognitive impairment.46

ASSOCIATED CLINICAL INSTRUMENTS

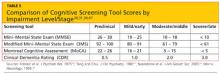

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a useful tool for staging cognitive decline, regardless of the patient’s diagnosis.47 It uses a 0-to-5 rating system in which 0 is considered normal and 5 represents profound impairment/total dependence (see Table 4,47-49 below). The CDR rating system addresses three areas of cognition (memory, orientation, judgment) and three areas of function (community affairs, home and hobbies, personal care). This tool is very helpful to explain to families where an individual with cognitive impairment is in the course of the disease, and what to expect and plan for in the future as the condition progresses. A comparison of CDR level and cognitive screening test scores is presented in Table 5.30,31,34,49

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a useful tool for staging cognitive decline, regardless of the patient’s diagnosis.47 It uses a 0-to-5 rating system in which 0 is considered normal and 5 represents profound impairment/total dependence (see Table 4,47-49 below). The CDR rating system addresses three areas of cognition (memory, orientation, judgment) and three areas of function (community affairs, home and hobbies, personal care). This tool is very helpful to explain to families where an individual with cognitive impairment is in the course of the disease, and what to expect and plan for in the future as the condition progresses. A comparison of CDR level and cognitive screening test scores is presented in Table 5.30,31,34,49

The Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST) focuses on the functional ability of the individual with cognitive deficits.50 It is a 16-item scale with scores from 0 to 7. Included in this tool are subscales addressing the more severely impaired levels associated with advanced dementia (eg, 6: dressing, bathing, toileting; and 7: speech and locomotion). The FAST has been adopted by CMS for use in evaluating nursing home residents and hospice patients.

Another tool that should be familiar to clinicians who work with cognitively impaired individuals is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).51 The CAM was developed to aid in identification and recognition of acute confusion and delirium, which often occur in older, hospitalized individuals. Four features are assessed in five minutes through observation and a brief in-person interview:

(1) Altered mental status from baseline (acute in onset or fluctuating)

(2) Inattention

(3) Disorganized thinking

(4) Altered level of consciousness (eg, hyperalert, lethargic, somnolent).

Delirium is considered present if there is evidence of features 1 and 2, and either 3 or 4 (or both).51

CONCLUSION

Clinicians in all settings need to become familiar with the use and interpretation of readily available instruments for cognitive screening. None of the tools reviewed is diagnostic in itself, and no one tool is appropriate for all patients in all settings. Familiarity with the components of the most commonly used cognitive screening tools and associated clinical instruments will aid the clinician in the appropriate use and interpretation of these to improve clinical care and outcomes for patients.

Clinicians in all settings need to become familiar with the use and interpretation of readily available instruments for cognitive screening. None of the tools reviewed is diagnostic in itself, and no one tool is appropriate for all patients in all settings. Familiarity with the components of the most commonly used cognitive screening tools and associated clinical instruments will aid the clinician in the appropriate use and interpretation of these to improve clinical care and outcomes for patients.

REFERENCES

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

2. Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, et al. Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138 (11):927-937.

3. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, HR 3590, 111th Cong, Public Law 111-148. www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

4. Congressional Research Service. Medicare provisions in PPACA (P. L. 111-148; 2010). http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/11-148_20100421.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

5. MedicareInteractive.org. Annual wellness visit. www.medicareinteractive.org/page2.php?topic=counselor&page=script&script_id=1717. Accessed December 11, 2012.

6. Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134-149.

7. Molnar FJ, Patel A, Marshall SC, et al. Clinical utility of office-based cognitive predictors of fitness to drive in persons with dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1809-1824.

8. Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1051-1059.

9. Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(4):169-73.

10. Hénon H, Durieu I, Guerouaou D, et al. Poststroke dementia: incidence and relationship to prestroke cognitive decline. Neurology. 2001;57(7):1216-1222.

11. Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1-2):125-132.

12. Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Ives DG, et al. Incidence and prevalence of dementia in the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):195-204.

13. Reisberg B, Gauthrie S. Current evidence for subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) as the pre-mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stage of subsequently manifest Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(1):1-16.

14. Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, et al. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530-538.

15. Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1133-1142.

16. Demeure MJ, Fain MJ. The elderly surgical patient and postoperative delirium [published correction appears in J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):191]. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(5):752-757.

17. Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303(8):763-770.

18. Terrando N, Brzezinski M, Degos V, et al. Perioperative cognitive decline in the aging population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(9):885-893.

19. Avidan MS, Evers AS. Review of clinical evidence for persistent cognitive decline or incident dementia attributable to surgery or general anesthesia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(2):201-216.

20. Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, et al. Cognitive decline after hospitalization in a community population of older persons. Neurology. 2012;78(13):950-956.

21. Milne A, Culverwell A, Guss R, et al. Screening for dementia in primary care: a review of the use, efficacy and quality of measures. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(5):911-926.

22. Chou KL, Amick MM, Brandt J, et al; Parkinson Study Group Cognitive/Psychiatric Working Group. A recommended scale for cognitive screening in clinical trials of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(15):2501-2507.

23. Murthy SB, Jawaid A, Schulz PE. Diabetes mellitus and dementia: advocating an annual cognitive screening in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1976-1977.

24. Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

25. Smith T, Gildeh N, Holmes C. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: validity and utility in a memory clinic setting. Can J Psychiatr. 2007;52 (5):329-332.

26. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini–mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder: a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910.

27. Brodaty H, Pond D, Kemp NM, et al. The GPCOG: a new screening test for dementia designed for general practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):530-534.

28. Buschke H, Kulansky G, Katz M, et al. Screening for dementia with the memory impairment screen. Neurology. 1999;52(2):231-238.

29. Lessig MC, Scanlan JM, Nazemi H, Borson S. Time that tells: critical clock-drawing errors for dementia screening. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008; 20(3):459-470.

30. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini–mental state: a practical tool for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

31. Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini–Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(8):314-318.

32. Sunderland T, Hill JL, Mellow AM, et al. Clock drawing in Alzheimer’s disease. A novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(8):725-729.

33. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, et al. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021-1027.

34. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699.

35. Mungas D, Marshall SC, Weldon M, et al. Age and education correction of the Mini–Mental State Examination for English- and Spanish-speaking elderly. Neurology. 1996;46(3):700-706.

36. Grace J, Nadler JD, White DA, et al. Folstein vs modified Mini–Mental State Examination in geriatric stroke: stability, validity, and screening utility. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(5):477-484.

37. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8(6):487-496.

38. Diegelman NM, Gilbertson AD, Moore JL, et al. Validity of the Clock Drawing Test in predicting reports of driving problems in the elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2004:4:10.

39. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, et al. Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: comparison of the Mini-Cog and Mini–Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):871-874.

40. Harkness K, Demers C, Heckman GA, McKelvie RS. Screening for cognitive deficits using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Tool in outpatients ≥ 65 years of age with heart failure [published correction appears in Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(10):1537]. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(8):1203-1207.

41. Cruz-Oliver DM, Malmstrom TK, Allen CM, et al. The Veterans Affairs Saint Louis University mental status exam (SLUMS exam) and the Mini–mental status exam as predictors of mortality and institutionalization. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):636-641.

42. Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behavioral Neurol. 1988;1(2):111-117.

43. Welsh KA, Breitner JCS, Magruder-Habib KM. Detection of dementia in the elderly using Telephone Screening of Cognitive Status.Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol.1993;6:103-110.

44. Plassman BL, Newman TT, Welsh KA, et al. Properties of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status: application in epidemiological and longitudinal studies. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol.1994;7(3):235-241.

45. de Jager CA, Budge MM, Clarke R. Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(4):318-24.

46. Cook SE, Marsiske M, McCoy KJ. The use of the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M) in the detection of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;22(2):103-109.

47. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412-2414.

48. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566-572.

49. Heyman A, Wilkinson WE, Hurwitz BJ, et al. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: clinical predictors of institutionalization and death. Neurology. 1987;37(6):980-984.

50. Reisberg B. Functional assessment staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):653-659.

51. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method: a new method for detecting delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

Issue

Clinician Reviews - 23(1)

Publications

Topics

Page Number

12-18

Legacy Keywords

cognition, dementia, delirium, cognitive dysfunction, older adults, elderly, mini mental state exam, clock drawing test, mini-cog test, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Saint Louis University Mental Status, general practitioner assessment of cognition, memory impairment screen, telephone interview for cognitive status

Sections

As our elderly population continues to grow, the issues of screening for cognitive impairment and early detection of dementia are becoming increasingly important. Cognitive impairment, particularly in individuals who live alone, contributes to loss of independence, decreased quality of life, and increased health care costs.1 There are serious and costly implications of unrecognized dementia, including delayed treatment of reversible conditions, medication noncompliance for comorbid conditions, inaccurate and unreliable reporting by patients, safety concerns, potential catastrophes, and increased risk for victimization.

Clinicians in all settings can expect to care for increasing numbers of older adults—many with various degrees of cognitive difficulties. Such problems, especially if undetected, can significantly impact the ongoing management of both acute and chronic medical problems. In primary care settings, it has been reported, between 50% and 65% of patients found to have cognitive deficits meeting the criteria for dementia did not have a diagnosis of dementia noted in their medical record.2

The annual wellness examination provided for under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act3 (PPACA) for Medicare beneficiaries is required to include an assessment of cognitive function,4 but the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) have not, to date, recommended any specific screening instrument; examiners are expected to base their assessment on observation and reports from the patient and other informants.5

WHY DO TESTING?

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

It is well documented that dementia remains underrecognized and may indeed be the “silent epidemic” of this century.8 Current estimates are that the incidence of new cases of Alzheimer’s disease will double by 2050.9 Additionally, improvement in stroke survival rates means that there will likely be increases in vascular and poststroke dementia, as one-third of stroke patients have been found to develop a progressive dementia.10

The early detection of cognitive change offers benefits for both patients and providers. If early detection leads to a diagnosis of dementia (regardless of etiology), this can provide an explanation to patients and families regarding recent changes in function, mood, and behavior. A diagnosis of progressive dementia (eg, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia) provides an opportunity for early medication management, review and simplification of ongoing chronic disease management, and prevention of problems commonly associated with mismanagement. More importantly, early diagnosis of dementia enables patients to be more involved in planning for their own future care needs, such as execution of advance directives.

Cognitive screening may also help in identification of the at-risk driver or those who should undergo further assessment for fitness to drive.7

WHO SHOULD BE SCREENED?

There is no clear consensus on who should undergo cognitive screening or how frequently it should be carried out. Screening should be targeted at individuals who are at greatest risk for either progressive dementia or delirium. Advancing age is a known risk factor for dementia, but there is no agreement on a specific age at which to initiate cognitive screening. In patients older than 80, there is a 25% to 50% prevalence of dementia,1,11,12 thus suggesting that cognitive screening should be initiated before this age. Furthermore, clinicians who provide medical care for patients of advanced age must be increasingly attentive to the possible presence of cognitive decline.

There is no clear consensus on who should undergo cognitive screening or how frequently it should be carried out. Screening should be targeted at individuals who are at greatest risk for either progressive dementia or delirium. Advancing age is a known risk factor for dementia, but there is no agreement on a specific age at which to initiate cognitive screening. In patients older than 80, there is a 25% to 50% prevalence of dementia,1,11,12 thus suggesting that cognitive screening should be initiated before this age. Furthermore, clinicians who provide medical care for patients of advanced age must be increasingly attentive to the possible presence of cognitive decline.

Individuals with subjective memory complaints and those with a history of depression have been identified as being at high risk for dementia.13,14 The American Academy of Neurology recommends cognitive screening in any patient in whom cognitive impairment is suspected.15 This usually occurs when a family member or other individual close to the patient (eg, employer, friend) becomes concerned about changes in the patient’s thinking, behavior, or function. Additionally, older individuals who have recently undergone surgery or been hospitalized are a population at high risk for acute cognitive changes and should be considered candidates for mental status screening.16-20

Another population for whom cognitive screening may be appropriate is patients with certain medical conditions known to be associated with dementia, as well as any older person with unexplained functional decline. Examples of conditions associated with cognitive decline include Parkinson’s disease, a history of stroke, and diabetes mellitus.21-23

Most patients with memory difficulties and other cognitive problems do not report these complaints to their medical provider, and it is unrealistic to expect them to do so. Often it is a family member or a coworker who becomes aware of a problem and voices these concerns to the provider; however, the provider should not rely on this to ensure early detection.

Clinicians must be pro-active and maintain a high index of suspicion for cognitive difficulties, especially when treating adults older than 70 or 75. Becoming familiar with a variety of tools and using one or more regularly to determine whether an individual does or does not have cognitive changes that might warrant further assessment should be a routine part of care.

WHICH TEST TO USE?

There is no single, ideal cognitive screening tool that can be recommended for use in every clinical setting. However, the ideal tool would have high sensitivity (ie, the proportion of those with impairment correctly classified as impaired), high specificity (the proportion of those who are unimpaired correctly identified as not having cognitive problems; see Table 1,24-29 below), and a high positive predictive value (proportion identified by screening as impaired who really have cognitive impairment). Additionally, such a tool should be easy to administer and score, and should take a minimum amount of time to conduct in our time-pressured clinical environment.

There is no single, ideal cognitive screening tool that can be recommended for use in every clinical setting. However, the ideal tool would have high sensitivity (ie, the proportion of those with impairment correctly classified as impaired), high specificity (the proportion of those who are unimpaired correctly identified as not having cognitive problems; see Table 1,24-29 below), and a high positive predictive value (proportion identified by screening as impaired who really have cognitive impairment). Additionally, such a tool should be easy to administer and score, and should take a minimum amount of time to conduct in our time-pressured clinical environment.

Many of the currently available cognitive screening tests overemphasize memory to the neglect of other areas of cognitive function, such as executive function, language, and praxis, which can be impacted in patients with various conditions.24 One review of cognitive screening tests suggests that a comprehensive screening instrument should include six core neuropsychologic domains that are most commonly affected in the early stages of different dementias:

• Executive function

• Abstract reasoning

• Attention/working memory

• New verbal learning and recall

• Expressive language

• Visuospatial construction.24

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT SCREENING TESTS

Cognitive screening does involve some risk, and every tool has known limitations. A significant barrier can be the administration time required, possibly ranging from five to 20 minutes. There is a potential for false-positive results, and there can be distress and stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, for both patients and families.

Cognitive screening does involve some risk, and every tool has known limitations. A significant barrier can be the administration time required, possibly ranging from five to 20 minutes. There is a potential for false-positive results, and there can be distress and stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, for both patients and families.

The majority of cognitive screening tests were developed and validated using cohorts of English-speaking patients. When used in other populations, such as those with English as a second (or third) language, or when used in translation, the results may not be valid. Similarly, many tests have an inherent educational bias, presuming attainment of an eighth-grade level or higher—again calling results into question when the test is conducted in people with less formal education. Further, most of the currently available tools are insensitive to small changes, as they were designed for screening, not to detect changes in a patient over time.

Screening tests may have a ceiling effect, that is, they may be insensitive to changes among patients with high intelligence or high levels of education premorbidity. Some tests may also have a floor effect, lacking the ability to assess for change in patients below a certain level of education or intelligence. The summary scores of these tests have cut-offs for normal and may allow broad-range classification of levels of impairment as mild, moderate, or severe; this is not very useful in distinguishing different patterns of cognitive loss.

COGNITIVE SCREENING TOOLS

A variety of tools are available for bedside/clinical assessment of cognition (see Table 226,30-34 below). Their administration can be learned without difficulty, and they can be conducted with relative ease to provide insight into a patient’s cognitive abilities and deficits.

A variety of tools are available for bedside/clinical assessment of cognition (see Table 226,30-34 below). Their administration can be learned without difficulty, and they can be conducted with relative ease to provide insight into a patient’s cognitive abilities and deficits.

Mini–Mental State Exam

The most commonly used cognitive screening tool is the Folstein Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE).30 With administration taking about 15 minutes, the MMSE includes assessment of attention, orientation, registration, recall/short-term memory, language, and visuospatial construction. Clinicians will find this tool most useful in assessing the individual with suspected early dementia and to follow progression through the early and middle stages of cognitive decline in those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders.

The most commonly used cognitive screening tool is the Folstein Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE).30 With administration taking about 15 minutes, the MMSE includes assessment of attention, orientation, registration, recall/short-term memory, language, and visuospatial construction. Clinicians will find this tool most useful in assessing the individual with suspected early dementia and to follow progression through the early and middle stages of cognitive decline in those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders.

The maximum score is 30 points, with impairment suspected in subjects whose score is 25 or lower. The MMSE is highly dependent on verbal memory, and it does not include any tests of executive function; performance can be influenced by education and cultural background. A formula has been developed that takes age and education into account, allowing for correction of the score35 (see Table 335). The MMSE is currently a proprietary document requiring payment for its use.

The Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS)31 expands upon the MMSE with the addition of items that address remote memory, delayed recall, list generation, and judgment and reasoning. With a maximum score of 100 points, it allows for partially correct responses to be scored. For example, on verbal recall, cuing and choices are provided, with subsequent correct answers awarded partial points (ie, 1 or 2 points out of a 3-point maximum score per recall item). Cognitive impairment is defined by a score of 85 points or less.

The 3MS may be more sensitive in identification of early dementia than is the MMSE. The 3MS’s expanded item scoring may be helpful in differentiating between some of the clinical dementia subtypes, such as Alzheimer’s versus vascular dementia.36

Clock Drawing Test

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is perhaps the simplest test to administer.29,32 The patient is given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw a large circle, then to write numbers inside the circle so that it resembles a face of a clock. Once this is completed, the patient is instructed to “draw the hands on the clock to read ten past eleven.”

The Clock Drawing Test (CDT) is perhaps the simplest test to administer.29,32 The patient is given a blank sheet of paper and asked to draw a large circle, then to write numbers inside the circle so that it resembles a face of a clock. Once this is completed, the patient is instructed to “draw the hands on the clock to read ten past eleven.”

There are multiple scoring systems for the CDT,29,32,37 with points given for accuracy of placement of the numbers and the size and position of the hands. Lower scores generally indicate greater impairment. The advantages of the CDT are that it is not very threatening, it is very sensitive to changes in early Alzheimer’s disease, and its administration requires little training.29 It has also been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety.38

The CDT is most appropriate for screening in busy practices and other settings (eg, health fairs) where further evaluation can be relied upon to identify any false-positive test results.

Mini-Cog Test

The Mini-Cog Test (with instructions available at http://geriatrics.uthscsa.edu/tools/MINICog.pdf) includes the clock-drawing task and a three-word recall, with a simple scoring algorithm.33 Ability to recall all three words, or to recall one or two words with normal results on the clock test, represents a negative screening result for dementia. Conversely, an inability to recall any of the three words, or ability to recall only one or two words with an abnormal clock test, is considered a positive screen for dementia. The Mini-Cog is a good tool for identification of early dementia, but not useful for following changes in individuals identified with cognitive impairment.

The Mini-Cog Test (with instructions available at http://geriatrics.uthscsa.edu/tools/MINICog.pdf) includes the clock-drawing task and a three-word recall, with a simple scoring algorithm.33 Ability to recall all three words, or to recall one or two words with normal results on the clock test, represents a negative screening result for dementia. Conversely, an inability to recall any of the three words, or ability to recall only one or two words with an abnormal clock test, is considered a positive screen for dementia. The Mini-Cog is a good tool for identification of early dementia, but not useful for following changes in individuals identified with cognitive impairment.

The Mini-Cog has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE, but it is much briefer and easier to administer. It is also less prone to language or ethnic bias, making it appropriate for patients with a wide variety of backgrounds and educational levels, and it translates easily for use in other languages.33,39

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was originally designed as a brief screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment.34 It is a single-page, 30-point test, available in multiple languages (with several versions in some languages) at www.mocatest.org. The MoCA includes assessment of short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation. A score of 25 or lower is considered subnormal.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was originally designed as a brief screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment.34 It is a single-page, 30-point test, available in multiple languages (with several versions in some languages) at www.mocatest.org. The MoCA includes assessment of short-term memory, visuospatial ability, executive function, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and orientation. A score of 25 or lower is considered subnormal.

By design, the MoCA is useful for detecting subtle deficits that may be missed in patients who are highly educated, who score within the normal range on MMSE (≥ 25), or who have prominent executive dysfunction. The test has been shown to have excellent sensitivity in identification of early/mild cognitive changes and high test-retest reliability, and it is considered an excellent screening tool for detection of cognitive impairment in a busy clinical setting.40

Saint Louis University Mental Status

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) has also been shown to have better sensitivity than the MMSE for early cognitive changes.26 This 11-item tool, with a maximum score of 30 points, includes assessment of seven cognitive domains: orientation, recall, attention, calculation, fluency, language, and visuospatial construction. The five-item delayed recall in the SLUMS has been shown to be an excellent discriminator of those with normal cognition versus mild cognitive change. It is available for general use with no fee; currently, it is widely used by the Veterans Administration system.41

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) has also been shown to have better sensitivity than the MMSE for early cognitive changes.26 This 11-item tool, with a maximum score of 30 points, includes assessment of seven cognitive domains: orientation, recall, attention, calculation, fluency, language, and visuospatial construction. The five-item delayed recall in the SLUMS has been shown to be an excellent discriminator of those with normal cognition versus mild cognitive change. It is available for general use with no fee; currently, it is widely used by the Veterans Administration system.41

General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition

The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)27 is a unique two-part tool that includes questions for the patient and for someone who knows the patient well (“informant”). The patient items include memory/recall, orientation, and visuospatial tasks. The six informant questions ask about recall, language, and functional abilities. The GPCOG has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE27; as its name indicates, it is designed and best suited for screening in a family medicine or general internal medicine practice.

The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)27 is a unique two-part tool that includes questions for the patient and for someone who knows the patient well (“informant”). The patient items include memory/recall, orientation, and visuospatial tasks. The six informant questions ask about recall, language, and functional abilities. The GPCOG has been shown to have sensitivity and specificity similar to those of the MMSE27; as its name indicates, it is designed and best suited for screening in a family medicine or general internal medicine practice.

Memory Impairment Screen

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)28 uses a four-item memory recall with simple scoring of 0 to 8, based on the formula: 2x [the number recalled spontaneously) + (the number recalled with cuing)]. It takes less than five minutes to administer, making it a useful tool to screen for suspected memory problems in a busy setting, such as an emergency room. However, the sole reliance on memory, without screening for any other areas of cognition (especially executive function or visuospatial copying), significantly limits the usefulness of the MIS as a general cognitive screening tool.

The Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)28 uses a four-item memory recall with simple scoring of 0 to 8, based on the formula: 2x [the number recalled spontaneously) + (the number recalled with cuing)]. It takes less than five minutes to administer, making it a useful tool to screen for suspected memory problems in a busy setting, such as an emergency room. However, the sole reliance on memory, without screening for any other areas of cognition (especially executive function or visuospatial copying), significantly limits the usefulness of the MIS as a general cognitive screening tool.

Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status

The cognitive screening instruments described thus far were all designed to be administered in person in a medical setting (office, clinic, or hospital). The 11-item Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)42 was developed as a brief (taking less than 10 minutes) standardized test of cognitive function, specifically suited for situations in which in-person screening is not possible (eg, for patients who are unable to appear in person for clinical follow-up).42-44 The modified TICS (TICS-M), which includes 13 items, has been shown to have less of a ceiling effect than the MMSE.45 It has also been shown to be a cost-effective screening tool for mild cognitive impairment.46

The cognitive screening instruments described thus far were all designed to be administered in person in a medical setting (office, clinic, or hospital). The 11-item Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)42 was developed as a brief (taking less than 10 minutes) standardized test of cognitive function, specifically suited for situations in which in-person screening is not possible (eg, for patients who are unable to appear in person for clinical follow-up).42-44 The modified TICS (TICS-M), which includes 13 items, has been shown to have less of a ceiling effect than the MMSE.45 It has also been shown to be a cost-effective screening tool for mild cognitive impairment.46

ASSOCIATED CLINICAL INSTRUMENTS

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a useful tool for staging cognitive decline, regardless of the patient’s diagnosis.47 It uses a 0-to-5 rating system in which 0 is considered normal and 5 represents profound impairment/total dependence (see Table 4,47-49 below). The CDR rating system addresses three areas of cognition (memory, orientation, judgment) and three areas of function (community affairs, home and hobbies, personal care). This tool is very helpful to explain to families where an individual with cognitive impairment is in the course of the disease, and what to expect and plan for in the future as the condition progresses. A comparison of CDR level and cognitive screening test scores is presented in Table 5.30,31,34,49

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is a useful tool for staging cognitive decline, regardless of the patient’s diagnosis.47 It uses a 0-to-5 rating system in which 0 is considered normal and 5 represents profound impairment/total dependence (see Table 4,47-49 below). The CDR rating system addresses three areas of cognition (memory, orientation, judgment) and three areas of function (community affairs, home and hobbies, personal care). This tool is very helpful to explain to families where an individual with cognitive impairment is in the course of the disease, and what to expect and plan for in the future as the condition progresses. A comparison of CDR level and cognitive screening test scores is presented in Table 5.30,31,34,49

The Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST) focuses on the functional ability of the individual with cognitive deficits.50 It is a 16-item scale with scores from 0 to 7. Included in this tool are subscales addressing the more severely impaired levels associated with advanced dementia (eg, 6: dressing, bathing, toileting; and 7: speech and locomotion). The FAST has been adopted by CMS for use in evaluating nursing home residents and hospice patients.

Another tool that should be familiar to clinicians who work with cognitively impaired individuals is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).51 The CAM was developed to aid in identification and recognition of acute confusion and delirium, which often occur in older, hospitalized individuals. Four features are assessed in five minutes through observation and a brief in-person interview:

(1) Altered mental status from baseline (acute in onset or fluctuating)

(2) Inattention

(3) Disorganized thinking

(4) Altered level of consciousness (eg, hyperalert, lethargic, somnolent).

Delirium is considered present if there is evidence of features 1 and 2, and either 3 or 4 (or both).51

CONCLUSION

Clinicians in all settings need to become familiar with the use and interpretation of readily available instruments for cognitive screening. None of the tools reviewed is diagnostic in itself, and no one tool is appropriate for all patients in all settings. Familiarity with the components of the most commonly used cognitive screening tools and associated clinical instruments will aid the clinician in the appropriate use and interpretation of these to improve clinical care and outcomes for patients.

Clinicians in all settings need to become familiar with the use and interpretation of readily available instruments for cognitive screening. None of the tools reviewed is diagnostic in itself, and no one tool is appropriate for all patients in all settings. Familiarity with the components of the most commonly used cognitive screening tools and associated clinical instruments will aid the clinician in the appropriate use and interpretation of these to improve clinical care and outcomes for patients.

REFERENCES

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

2. Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, et al. Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138 (11):927-937.

3. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, HR 3590, 111th Cong, Public Law 111-148. www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

4. Congressional Research Service. Medicare provisions in PPACA (P. L. 111-148; 2010). http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/11-148_20100421.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

5. MedicareInteractive.org. Annual wellness visit. www.medicareinteractive.org/page2.php?topic=counselor&page=script&script_id=1717. Accessed December 11, 2012.

6. Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134-149.

7. Molnar FJ, Patel A, Marshall SC, et al. Clinical utility of office-based cognitive predictors of fitness to drive in persons with dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1809-1824.

8. Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1051-1059.

9. Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(4):169-73.

10. Hénon H, Durieu I, Guerouaou D, et al. Poststroke dementia: incidence and relationship to prestroke cognitive decline. Neurology. 2001;57(7):1216-1222.

11. Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1-2):125-132.

12. Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Ives DG, et al. Incidence and prevalence of dementia in the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):195-204.

13. Reisberg B, Gauthrie S. Current evidence for subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) as the pre-mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stage of subsequently manifest Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(1):1-16.

14. Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, et al. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530-538.

15. Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1133-1142.

16. Demeure MJ, Fain MJ. The elderly surgical patient and postoperative delirium [published correction appears in J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):191]. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(5):752-757.

17. Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303(8):763-770.

18. Terrando N, Brzezinski M, Degos V, et al. Perioperative cognitive decline in the aging population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(9):885-893.

19. Avidan MS, Evers AS. Review of clinical evidence for persistent cognitive decline or incident dementia attributable to surgery or general anesthesia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(2):201-216.

20. Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, et al. Cognitive decline after hospitalization in a community population of older persons. Neurology. 2012;78(13):950-956.

21. Milne A, Culverwell A, Guss R, et al. Screening for dementia in primary care: a review of the use, efficacy and quality of measures. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(5):911-926.

22. Chou KL, Amick MM, Brandt J, et al; Parkinson Study Group Cognitive/Psychiatric Working Group. A recommended scale for cognitive screening in clinical trials of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(15):2501-2507.

23. Murthy SB, Jawaid A, Schulz PE. Diabetes mellitus and dementia: advocating an annual cognitive screening in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1976-1977.

24. Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

25. Smith T, Gildeh N, Holmes C. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: validity and utility in a memory clinic setting. Can J Psychiatr. 2007;52 (5):329-332.

26. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini–mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder: a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910.

27. Brodaty H, Pond D, Kemp NM, et al. The GPCOG: a new screening test for dementia designed for general practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):530-534.

28. Buschke H, Kulansky G, Katz M, et al. Screening for dementia with the memory impairment screen. Neurology. 1999;52(2):231-238.

29. Lessig MC, Scanlan JM, Nazemi H, Borson S. Time that tells: critical clock-drawing errors for dementia screening. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008; 20(3):459-470.

30. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini–mental state: a practical tool for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

31. Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini–Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(8):314-318.

32. Sunderland T, Hill JL, Mellow AM, et al. Clock drawing in Alzheimer’s disease. A novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(8):725-729.

33. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, et al. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021-1027.

34. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699.

35. Mungas D, Marshall SC, Weldon M, et al. Age and education correction of the Mini–Mental State Examination for English- and Spanish-speaking elderly. Neurology. 1996;46(3):700-706.

36. Grace J, Nadler JD, White DA, et al. Folstein vs modified Mini–Mental State Examination in geriatric stroke: stability, validity, and screening utility. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(5):477-484.

37. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8(6):487-496.

38. Diegelman NM, Gilbertson AD, Moore JL, et al. Validity of the Clock Drawing Test in predicting reports of driving problems in the elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2004:4:10.

39. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, et al. Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: comparison of the Mini-Cog and Mini–Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):871-874.

40. Harkness K, Demers C, Heckman GA, McKelvie RS. Screening for cognitive deficits using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Tool in outpatients ≥ 65 years of age with heart failure [published correction appears in Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(10):1537]. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(8):1203-1207.

41. Cruz-Oliver DM, Malmstrom TK, Allen CM, et al. The Veterans Affairs Saint Louis University mental status exam (SLUMS exam) and the Mini–mental status exam as predictors of mortality and institutionalization. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):636-641.

42. Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behavioral Neurol. 1988;1(2):111-117.

43. Welsh KA, Breitner JCS, Magruder-Habib KM. Detection of dementia in the elderly using Telephone Screening of Cognitive Status.Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol.1993;6:103-110.

44. Plassman BL, Newman TT, Welsh KA, et al. Properties of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status: application in epidemiological and longitudinal studies. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol.1994;7(3):235-241.

45. de Jager CA, Budge MM, Clarke R. Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(4):318-24.

46. Cook SE, Marsiske M, McCoy KJ. The use of the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M) in the detection of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;22(2):103-109.

47. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412-2414.

48. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566-572.

49. Heyman A, Wilkinson WE, Hurwitz BJ, et al. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: clinical predictors of institutionalization and death. Neurology. 1987;37(6):980-984.

50. Reisberg B. Functional assessment staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):653-659.

51. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method: a new method for detecting delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

As our elderly population continues to grow, the issues of screening for cognitive impairment and early detection of dementia are becoming increasingly important. Cognitive impairment, particularly in individuals who live alone, contributes to loss of independence, decreased quality of life, and increased health care costs.1 There are serious and costly implications of unrecognized dementia, including delayed treatment of reversible conditions, medication noncompliance for comorbid conditions, inaccurate and unreliable reporting by patients, safety concerns, potential catastrophes, and increased risk for victimization.

Clinicians in all settings can expect to care for increasing numbers of older adults—many with various degrees of cognitive difficulties. Such problems, especially if undetected, can significantly impact the ongoing management of both acute and chronic medical problems. In primary care settings, it has been reported, between 50% and 65% of patients found to have cognitive deficits meeting the criteria for dementia did not have a diagnosis of dementia noted in their medical record.2

The annual wellness examination provided for under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act3 (PPACA) for Medicare beneficiaries is required to include an assessment of cognitive function,4 but the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) have not, to date, recommended any specific screening instrument; examiners are expected to base their assessment on observation and reports from the patient and other informants.5

WHY DO TESTING?

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

The purpose of cognitive screening tests is to aid the clinician in early detection of cognitive change as a first step toward accurate diagnosis—a process that requires further assessment. Such changes may herald the beginning of a dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or may indicate an increased risk for delirium, such as in the postoperative setting,6 or functional decline with accompanying safety concerns.7 Early identification of cognitive changes provides an opportunity for case finding, crisis avoidance, and identification of patients for earlier intervention and management, including a discussion of goals with the patient, and assurance that advance directives are complete and accurate.

It is well documented that dementia remains underrecognized and may indeed be the “silent epidemic” of this century.8 Current estimates are that the incidence of new cases of Alzheimer’s disease will double by 2050.9 Additionally, improvement in stroke survival rates means that there will likely be increases in vascular and poststroke dementia, as one-third of stroke patients have been found to develop a progressive dementia.10

The early detection of cognitive change offers benefits for both patients and providers. If early detection leads to a diagnosis of dementia (regardless of etiology), this can provide an explanation to patients and families regarding recent changes in function, mood, and behavior. A diagnosis of progressive dementia (eg, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia) provides an opportunity for early medication management, review and simplification of ongoing chronic disease management, and prevention of problems commonly associated with mismanagement. More importantly, early diagnosis of dementia enables patients to be more involved in planning for their own future care needs, such as execution of advance directives.

Cognitive screening may also help in identification of the at-risk driver or those who should undergo further assessment for fitness to drive.7

WHO SHOULD BE SCREENED?