User login

Story

Mr. M, a 70-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic atrial fibrillation, presented to his local hospital with a 3- to 4-day history of nausea and emesis that had become coffee-ground in description. Mr. M was on chronic Coumadin therapy, and his INR (international normalized ratio) in the emergency department was 5.78. The ED physician contacted Dr. Hospitalist for admission with a working diagnosis of gastritis and coagulopathy.

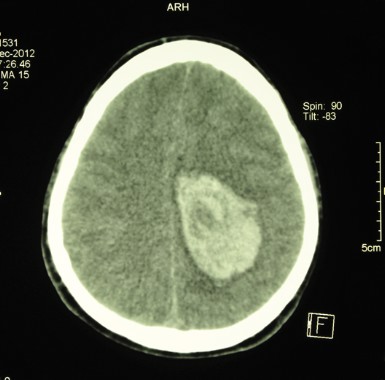

Dr. Hospitalist gave the ED verbal admission orders and awaited Mr. M’s transfer to the floor. By 11:30 p.m., Mr. M was in his hospital room. Shortly after his arrival the admission nurse heard a loud bang. When she entered the room, she found Mr. M lying flat on his back on the floor. Dr. Hospitalist was notified and she ordered a stat head CT that demonstrated small bifrontal hemorrhagic contusions, a small amount of adjacent subarachnoid hemorrhage, and a small subdural bleed along the right anterior cranial fossa.

Dr. Hospitalist examined Mr. M at 2 a.m. and noted he was confused. Dr. Hospitalist contacted the neurosurgeon on call and discussed Mr. M’s head CT result. Following this phone call, Dr. Hospitalist placed orders for activated factor VII, a transfer to the neuro-ICU, and a repeat head CT in 24 hours.

One hour later, Mr. M was still on the regular nursing floor. At 3:30 a.m., Mr. M vomited, and Dr. Hospitalist was notified. A nasogastric tube and physical restraints were ordered. At 4:30 a.m., Mr. M was transferred to the neuro-ICU. The ICU nurse documented that Mr. M was agitated, confused, irritable, and unable to focus and follow commands, and had unequal pupils, garbled speech, and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 12. At 5 a.m., Mr. M received activated factor VII.

By 6:30 a.m., Mr. M was drowsy, nonverbal, not following commands, had unequal pupils with minimal light response, left-sided weakness, and a GCS score of 7. Dr. Hospitalist was notified and a stat head CT was repeated. The head CT showed interval development of a large subdural hematoma over the right hemisphere with considerable left shift. At 7:30 a.m., Mr. M was examined by the neurosurgeon. At this point, Mr. M had irregular respirations, he was nonresponsive to painful stimuli, and all extremities displayed weak withdrawal effort. Mr. M was rushed to the operating room to evacuate the hematoma, but he never again regained consciousness.

Mr. M experienced progressive neurologic deterioration until his life support was withdrawn 2 days later.

Complaint

Shortly after the death of her husband, the widow contacted an attorney. The complaint alleged that both Dr. Hospitalist and the neurosurgeon carelessly failed to properly examine, monitor, and treat Mr. M’s intracranial bleed.

The complaint explained that Dr. Hospitalist essentially abandoned Mr. M, failing to ensure a timely transfer to the neuro-ICU and the administration of activated factor VII. The complaint was also critical that Dr. Hospitalist didn’t immediately reverse the coagulopathy with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and intravenous vitamin K. Had Dr. Hospitalist and the neurosurgeon acted in accordance with the prevailing standards of care, Mr. M’s intracranial bleed would have been stabilized without permanent injury, the complaint stated.

Scientific principles

Intracerebral bleeding in an anticoagulated patient, either spontaneous or trauma-induced, is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment. Options for correction of an elevated INR include vitamin K, FFP, prothrombin complex concentrates (PCC), and activated factor VII.

The decision to use FFP or PCC for reversal depends on the availability of PCC and the degree of prolongation of the INR. If PCC is available, it will provide the most rapid reversal. Regardless of the preparations used, it is extremely important to minimize delays in their administration, in hopes of reducing the high mortality and morbidity.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Dr. Hospitalist defended herself by asserting that she contacted the neurosurgeon and discussed the case and the CT findings, and she relied on his expertise from that moment forward. Dr. Hospitalist further testified that the neurosurgeon specifically told her not to give vitamin K or FFP, but to give activated factor VII instead.

Dr. Hospitalist admitted that she had never treated a case of intracerebral hemorrhage before this one and certainly had never ordered activated clotting factors on her own.

The neurosurgeon testified he had no specific memory of this case or the phone call with Dr. Hospitalist, but he does not believe he would have told Dr. Hospitalist not to give vitamin K or FFP. In fact, the neurosurgery consult note clearly documented the expectation that Mr. M receive all three reversal treatments (vitamin K, FFP, and factor VIIa). More importantly, the consult note also documented the neurosurgeon’s surprise and dismay to find Mr. M in such extremis. The neurosurgeon testified that had he been aware of Mr. M’s true neurological condition, he would have intervened promptly.

Conclusion

This case incorporates several important issues previously addressed in this column over the past year. First, hospitalists need to appreciate the significance of anticoagulation and be well versed on how to correct excessive anticoagulation with or without bleeding ("Think before reversing anticoagulants").

Second, hospitalists must communicate and document clear expectations and boundaries of responsibility when working with subspecialty consultants and surgeons ("A real pain in the neck" and "Beyond the scope").

Third, regardless of consultant and/or subspecialty expertise, hospitalists are still responsible for their own scope of practice within their training, background, and experience. Hospitalists should not blindly defer to a consultant, and conversations regarding patient plans of care should be memorialized in the patient chart ("Overreliance on subspecialty in a case of endocarditis").

Had the hospitalist in this case documented her initial conversation with the neurosurgeon with an explicit transfer of responsibility regarding the intracranial bleed, it is likely that the legal outcome would have been different. As it was, the neurosurgeon in this case was eventually dropped by the plaintiff.

Dr. Hospitalist, on the other hand, ended up settling with the widow for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

Story

Mr. M, a 70-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic atrial fibrillation, presented to his local hospital with a 3- to 4-day history of nausea and emesis that had become coffee-ground in description. Mr. M was on chronic Coumadin therapy, and his INR (international normalized ratio) in the emergency department was 5.78. The ED physician contacted Dr. Hospitalist for admission with a working diagnosis of gastritis and coagulopathy.

Dr. Hospitalist gave the ED verbal admission orders and awaited Mr. M’s transfer to the floor. By 11:30 p.m., Mr. M was in his hospital room. Shortly after his arrival the admission nurse heard a loud bang. When she entered the room, she found Mr. M lying flat on his back on the floor. Dr. Hospitalist was notified and she ordered a stat head CT that demonstrated small bifrontal hemorrhagic contusions, a small amount of adjacent subarachnoid hemorrhage, and a small subdural bleed along the right anterior cranial fossa.

Dr. Hospitalist examined Mr. M at 2 a.m. and noted he was confused. Dr. Hospitalist contacted the neurosurgeon on call and discussed Mr. M’s head CT result. Following this phone call, Dr. Hospitalist placed orders for activated factor VII, a transfer to the neuro-ICU, and a repeat head CT in 24 hours.

One hour later, Mr. M was still on the regular nursing floor. At 3:30 a.m., Mr. M vomited, and Dr. Hospitalist was notified. A nasogastric tube and physical restraints were ordered. At 4:30 a.m., Mr. M was transferred to the neuro-ICU. The ICU nurse documented that Mr. M was agitated, confused, irritable, and unable to focus and follow commands, and had unequal pupils, garbled speech, and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 12. At 5 a.m., Mr. M received activated factor VII.

By 6:30 a.m., Mr. M was drowsy, nonverbal, not following commands, had unequal pupils with minimal light response, left-sided weakness, and a GCS score of 7. Dr. Hospitalist was notified and a stat head CT was repeated. The head CT showed interval development of a large subdural hematoma over the right hemisphere with considerable left shift. At 7:30 a.m., Mr. M was examined by the neurosurgeon. At this point, Mr. M had irregular respirations, he was nonresponsive to painful stimuli, and all extremities displayed weak withdrawal effort. Mr. M was rushed to the operating room to evacuate the hematoma, but he never again regained consciousness.

Mr. M experienced progressive neurologic deterioration until his life support was withdrawn 2 days later.

Complaint

Shortly after the death of her husband, the widow contacted an attorney. The complaint alleged that both Dr. Hospitalist and the neurosurgeon carelessly failed to properly examine, monitor, and treat Mr. M’s intracranial bleed.

The complaint explained that Dr. Hospitalist essentially abandoned Mr. M, failing to ensure a timely transfer to the neuro-ICU and the administration of activated factor VII. The complaint was also critical that Dr. Hospitalist didn’t immediately reverse the coagulopathy with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and intravenous vitamin K. Had Dr. Hospitalist and the neurosurgeon acted in accordance with the prevailing standards of care, Mr. M’s intracranial bleed would have been stabilized without permanent injury, the complaint stated.

Scientific principles

Intracerebral bleeding in an anticoagulated patient, either spontaneous or trauma-induced, is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment. Options for correction of an elevated INR include vitamin K, FFP, prothrombin complex concentrates (PCC), and activated factor VII.

The decision to use FFP or PCC for reversal depends on the availability of PCC and the degree of prolongation of the INR. If PCC is available, it will provide the most rapid reversal. Regardless of the preparations used, it is extremely important to minimize delays in their administration, in hopes of reducing the high mortality and morbidity.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Dr. Hospitalist defended herself by asserting that she contacted the neurosurgeon and discussed the case and the CT findings, and she relied on his expertise from that moment forward. Dr. Hospitalist further testified that the neurosurgeon specifically told her not to give vitamin K or FFP, but to give activated factor VII instead.

Dr. Hospitalist admitted that she had never treated a case of intracerebral hemorrhage before this one and certainly had never ordered activated clotting factors on her own.

The neurosurgeon testified he had no specific memory of this case or the phone call with Dr. Hospitalist, but he does not believe he would have told Dr. Hospitalist not to give vitamin K or FFP. In fact, the neurosurgery consult note clearly documented the expectation that Mr. M receive all three reversal treatments (vitamin K, FFP, and factor VIIa). More importantly, the consult note also documented the neurosurgeon’s surprise and dismay to find Mr. M in such extremis. The neurosurgeon testified that had he been aware of Mr. M’s true neurological condition, he would have intervened promptly.

Conclusion

This case incorporates several important issues previously addressed in this column over the past year. First, hospitalists need to appreciate the significance of anticoagulation and be well versed on how to correct excessive anticoagulation with or without bleeding ("Think before reversing anticoagulants").

Second, hospitalists must communicate and document clear expectations and boundaries of responsibility when working with subspecialty consultants and surgeons ("A real pain in the neck" and "Beyond the scope").

Third, regardless of consultant and/or subspecialty expertise, hospitalists are still responsible for their own scope of practice within their training, background, and experience. Hospitalists should not blindly defer to a consultant, and conversations regarding patient plans of care should be memorialized in the patient chart ("Overreliance on subspecialty in a case of endocarditis").

Had the hospitalist in this case documented her initial conversation with the neurosurgeon with an explicit transfer of responsibility regarding the intracranial bleed, it is likely that the legal outcome would have been different. As it was, the neurosurgeon in this case was eventually dropped by the plaintiff.

Dr. Hospitalist, on the other hand, ended up settling with the widow for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

Story

Mr. M, a 70-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic atrial fibrillation, presented to his local hospital with a 3- to 4-day history of nausea and emesis that had become coffee-ground in description. Mr. M was on chronic Coumadin therapy, and his INR (international normalized ratio) in the emergency department was 5.78. The ED physician contacted Dr. Hospitalist for admission with a working diagnosis of gastritis and coagulopathy.

Dr. Hospitalist gave the ED verbal admission orders and awaited Mr. M’s transfer to the floor. By 11:30 p.m., Mr. M was in his hospital room. Shortly after his arrival the admission nurse heard a loud bang. When she entered the room, she found Mr. M lying flat on his back on the floor. Dr. Hospitalist was notified and she ordered a stat head CT that demonstrated small bifrontal hemorrhagic contusions, a small amount of adjacent subarachnoid hemorrhage, and a small subdural bleed along the right anterior cranial fossa.

Dr. Hospitalist examined Mr. M at 2 a.m. and noted he was confused. Dr. Hospitalist contacted the neurosurgeon on call and discussed Mr. M’s head CT result. Following this phone call, Dr. Hospitalist placed orders for activated factor VII, a transfer to the neuro-ICU, and a repeat head CT in 24 hours.

One hour later, Mr. M was still on the regular nursing floor. At 3:30 a.m., Mr. M vomited, and Dr. Hospitalist was notified. A nasogastric tube and physical restraints were ordered. At 4:30 a.m., Mr. M was transferred to the neuro-ICU. The ICU nurse documented that Mr. M was agitated, confused, irritable, and unable to focus and follow commands, and had unequal pupils, garbled speech, and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 12. At 5 a.m., Mr. M received activated factor VII.

By 6:30 a.m., Mr. M was drowsy, nonverbal, not following commands, had unequal pupils with minimal light response, left-sided weakness, and a GCS score of 7. Dr. Hospitalist was notified and a stat head CT was repeated. The head CT showed interval development of a large subdural hematoma over the right hemisphere with considerable left shift. At 7:30 a.m., Mr. M was examined by the neurosurgeon. At this point, Mr. M had irregular respirations, he was nonresponsive to painful stimuli, and all extremities displayed weak withdrawal effort. Mr. M was rushed to the operating room to evacuate the hematoma, but he never again regained consciousness.

Mr. M experienced progressive neurologic deterioration until his life support was withdrawn 2 days later.

Complaint

Shortly after the death of her husband, the widow contacted an attorney. The complaint alleged that both Dr. Hospitalist and the neurosurgeon carelessly failed to properly examine, monitor, and treat Mr. M’s intracranial bleed.

The complaint explained that Dr. Hospitalist essentially abandoned Mr. M, failing to ensure a timely transfer to the neuro-ICU and the administration of activated factor VII. The complaint was also critical that Dr. Hospitalist didn’t immediately reverse the coagulopathy with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and intravenous vitamin K. Had Dr. Hospitalist and the neurosurgeon acted in accordance with the prevailing standards of care, Mr. M’s intracranial bleed would have been stabilized without permanent injury, the complaint stated.

Scientific principles

Intracerebral bleeding in an anticoagulated patient, either spontaneous or trauma-induced, is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment. Options for correction of an elevated INR include vitamin K, FFP, prothrombin complex concentrates (PCC), and activated factor VII.

The decision to use FFP or PCC for reversal depends on the availability of PCC and the degree of prolongation of the INR. If PCC is available, it will provide the most rapid reversal. Regardless of the preparations used, it is extremely important to minimize delays in their administration, in hopes of reducing the high mortality and morbidity.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Dr. Hospitalist defended herself by asserting that she contacted the neurosurgeon and discussed the case and the CT findings, and she relied on his expertise from that moment forward. Dr. Hospitalist further testified that the neurosurgeon specifically told her not to give vitamin K or FFP, but to give activated factor VII instead.

Dr. Hospitalist admitted that she had never treated a case of intracerebral hemorrhage before this one and certainly had never ordered activated clotting factors on her own.

The neurosurgeon testified he had no specific memory of this case or the phone call with Dr. Hospitalist, but he does not believe he would have told Dr. Hospitalist not to give vitamin K or FFP. In fact, the neurosurgery consult note clearly documented the expectation that Mr. M receive all three reversal treatments (vitamin K, FFP, and factor VIIa). More importantly, the consult note also documented the neurosurgeon’s surprise and dismay to find Mr. M in such extremis. The neurosurgeon testified that had he been aware of Mr. M’s true neurological condition, he would have intervened promptly.

Conclusion

This case incorporates several important issues previously addressed in this column over the past year. First, hospitalists need to appreciate the significance of anticoagulation and be well versed on how to correct excessive anticoagulation with or without bleeding ("Think before reversing anticoagulants").

Second, hospitalists must communicate and document clear expectations and boundaries of responsibility when working with subspecialty consultants and surgeons ("A real pain in the neck" and "Beyond the scope").

Third, regardless of consultant and/or subspecialty expertise, hospitalists are still responsible for their own scope of practice within their training, background, and experience. Hospitalists should not blindly defer to a consultant, and conversations regarding patient plans of care should be memorialized in the patient chart ("Overreliance on subspecialty in a case of endocarditis").

Had the hospitalist in this case documented her initial conversation with the neurosurgeon with an explicit transfer of responsibility regarding the intracranial bleed, it is likely that the legal outcome would have been different. As it was, the neurosurgeon in this case was eventually dropped by the plaintiff.

Dr. Hospitalist, on the other hand, ended up settling with the widow for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.