User login

The use of hormonal contraception in women with headaches, especially migraine headaches, is an important topic. Approximately 43% of women in the United States report migraines.1 Roughly the same percentage of reproductive-aged women use hormonal contraception.2 Data suggest that all migraineurs have some increased risk of stroke. Therefore, can women with migraine headaches use combination hormonal contraception? And can women with severe headaches that are nonmigrainous use combination hormonal contraception? Let’s examine available data to help us answer these questions.

Risk factors for stroke

Migraine without aura is the most common subset, but migraine with aura is more problematic relative to the increased incidence of stroke.1

A migraine aura is visual 90% of the time.1 Symptoms can include flickering lights, spots, zigzag lines, a sense of pins and needles, or dysphasic speech. Aura precedes the headache and usually resolves within 1 hour after the aura begins.

In addition to migraine headaches, risk factors for stroke include increasing age, hypertension, the use of combination oral contraceptives (COCs), the contraceptive patch and ring, and smoking.1

Data indicate that the risk for ischemic stroke is increased in women with migraines even without the presence of other risk factors. In a meta-analysis of 14 observational studies, the risk of ischemic stroke among all migraineurs was about 2-fold (relative risk [RR], 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9–2.5) compared with the risk of ischemic stroke in women of the same age group who did not have migraine headaches. When there is migraine without aura, it was slightly less than 2-fold (RR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–3.2). The risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs with aura is increased more than 2 times compared with women without migraine (RR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.61–3.19).3 However, the absolute risk of ischemic stroke among reproductive-aged women is 11 per 100,000 women years.4

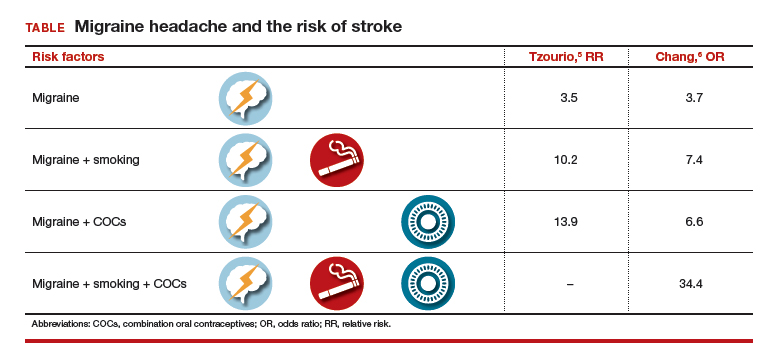

Two observational studies show how additional risk factors increase that risk (TABLE).5,6 There are similar trends in terms of overall risk of stroke among women with all types of migraine. However, when you add smoking as an additional risk factor for women with migraine headaches, there is a substantial increase in the risk of stroke. When a woman who has migraines uses COCs, there is increased risk varying from 2-fold to almost 4-fold. When you combine migraine, smoking, and COCs, a very, very large risk factor (odds ratio [OR], 34.4; 95% CI, 3.27–3.61) was reported by Chang and colleagues.6

Although these risks are impressive, it is important to keep in mind that even with a 10-fold increase, we are only talking about 1 case per 1,000 migraineurs.4 Unfortunately, stroke often leads to major disability and even death, such that any reduction in risk is still important.

Preventing estrogen withdrawal or menstrual migraines

How should we treat a woman who uses hormonal contraception and reports estrogen withdrawal or menstrual migraines? Based on clinical evidence, there are 2 ways to reduce her symptoms:

- COCs. Reduce the hormone-free interval by having her take COCs for 3 to 4 days instead of 7 days, or eliminate the hormone-free interval altogether by continuous use of COCs, usually 3 months at a time.7

- NSAIDs. For those who do not want to alter how they take their hormonal product, use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) starting 7 days before the onset of menses and continuing for 13 days. In a clinical trial by Sances and colleagues, this plan reduced the frequency, duration, and severity of menstrual migraines.8

Probably altering how she takes the COC would make the most sense for most individuals instead of taking NSAIDs for 75% of each month.

Recommendations from the US MEC

The US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers recommendations for contraceptive use9:

- For nonmigrainous headache, the CDC suggests that the benefits of using COCs outweigh the risks unless the headaches persist after 3 months of COC use.

- For migraine without aura, the benefits outweigh the risks in starting women who are younger than age 35 years on oral contraceptives. However, the risks of COCs outweigh the benefits in women who are age 35 years and older who develop migraine headache while on COCs, or who have risk factors for stroke.

- For migraine with aura, COCs are contraindicated.

- Progestin-only contraceptives. The CDC considers that the benefits of COC use outweigh any theoretical risk of stroke, even in women with risk factors or in women who have migraine with aura. Progestin-only contraceptives do not alter one’s risk of stroke, unlike contraceptives that contain estrogen.

My bottom line

Can women with migraine headaches begin the use of combination hormonal methods? Yes, if there is no aura in their migraines and they are not older than age 35.

Can women with severe headaches that are nonmigrainous use combination hormonal methods? Possibly, but you should discontinue COCs if headache severity persists or worsens, using a 3-month time period for evaluation.

How do you manage women with migraines during the hormone-free interval? Consider the continuous method or shorten the hormone-free interval.

Recommendations for complicated patients. Consulting the CDC’s US MEC database7 can provide assistance in your care of more complicated patients requesting contraception. I also recommend the book, “Contraception for the Medically Challenging Patient,” edited by Rebecca Allen and Carrie Cwiak.10 It links nicely with the CDC guidelines and presents more detail on each subject.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed MD, et al. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(11):1170–1178.

- Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):110–118.

- Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2005;330(7482):63–66.

- Petitti DB, Sydney S, Bernstein A, Wolf S, Quesenberry C, Ziel HK. Stoke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):8–15.

- Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglesias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310:830–833.

- Chang CL, Donaghy M, Poulter N. Migraine and stroke in young women: case-control study. The World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. BMJ. 1999;318(7175):13–18.

- Edelman A, Gallo MF, Nichols MD, Jensen JT, Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Continuous versus cyclic use of combined oral contraceptives for contraception: systematic Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(3):573–578.

- Sances G, Martignoni E, Fioroni L, Blandini F, Facchinetti F, Nappi G. Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache. 1990;30(11):705–709.

- US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1–86. https://www.cdc .gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2016.

- Allen RH, Cwiak CA, eds. Contraception for the medically challenging patient. New York, New York: Springer New York; 2014.

The use of hormonal contraception in women with headaches, especially migraine headaches, is an important topic. Approximately 43% of women in the United States report migraines.1 Roughly the same percentage of reproductive-aged women use hormonal contraception.2 Data suggest that all migraineurs have some increased risk of stroke. Therefore, can women with migraine headaches use combination hormonal contraception? And can women with severe headaches that are nonmigrainous use combination hormonal contraception? Let’s examine available data to help us answer these questions.

Risk factors for stroke

Migraine without aura is the most common subset, but migraine with aura is more problematic relative to the increased incidence of stroke.1

A migraine aura is visual 90% of the time.1 Symptoms can include flickering lights, spots, zigzag lines, a sense of pins and needles, or dysphasic speech. Aura precedes the headache and usually resolves within 1 hour after the aura begins.

In addition to migraine headaches, risk factors for stroke include increasing age, hypertension, the use of combination oral contraceptives (COCs), the contraceptive patch and ring, and smoking.1

Data indicate that the risk for ischemic stroke is increased in women with migraines even without the presence of other risk factors. In a meta-analysis of 14 observational studies, the risk of ischemic stroke among all migraineurs was about 2-fold (relative risk [RR], 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9–2.5) compared with the risk of ischemic stroke in women of the same age group who did not have migraine headaches. When there is migraine without aura, it was slightly less than 2-fold (RR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–3.2). The risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs with aura is increased more than 2 times compared with women without migraine (RR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.61–3.19).3 However, the absolute risk of ischemic stroke among reproductive-aged women is 11 per 100,000 women years.4

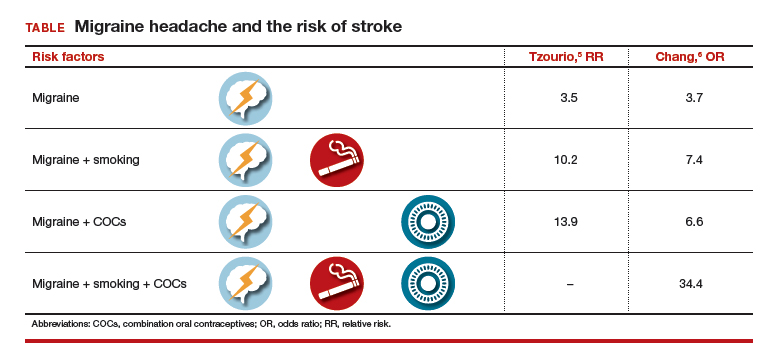

Two observational studies show how additional risk factors increase that risk (TABLE).5,6 There are similar trends in terms of overall risk of stroke among women with all types of migraine. However, when you add smoking as an additional risk factor for women with migraine headaches, there is a substantial increase in the risk of stroke. When a woman who has migraines uses COCs, there is increased risk varying from 2-fold to almost 4-fold. When you combine migraine, smoking, and COCs, a very, very large risk factor (odds ratio [OR], 34.4; 95% CI, 3.27–3.61) was reported by Chang and colleagues.6

Although these risks are impressive, it is important to keep in mind that even with a 10-fold increase, we are only talking about 1 case per 1,000 migraineurs.4 Unfortunately, stroke often leads to major disability and even death, such that any reduction in risk is still important.

Preventing estrogen withdrawal or menstrual migraines

How should we treat a woman who uses hormonal contraception and reports estrogen withdrawal or menstrual migraines? Based on clinical evidence, there are 2 ways to reduce her symptoms:

- COCs. Reduce the hormone-free interval by having her take COCs for 3 to 4 days instead of 7 days, or eliminate the hormone-free interval altogether by continuous use of COCs, usually 3 months at a time.7

- NSAIDs. For those who do not want to alter how they take their hormonal product, use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) starting 7 days before the onset of menses and continuing for 13 days. In a clinical trial by Sances and colleagues, this plan reduced the frequency, duration, and severity of menstrual migraines.8

Probably altering how she takes the COC would make the most sense for most individuals instead of taking NSAIDs for 75% of each month.

Recommendations from the US MEC

The US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers recommendations for contraceptive use9:

- For nonmigrainous headache, the CDC suggests that the benefits of using COCs outweigh the risks unless the headaches persist after 3 months of COC use.

- For migraine without aura, the benefits outweigh the risks in starting women who are younger than age 35 years on oral contraceptives. However, the risks of COCs outweigh the benefits in women who are age 35 years and older who develop migraine headache while on COCs, or who have risk factors for stroke.

- For migraine with aura, COCs are contraindicated.

- Progestin-only contraceptives. The CDC considers that the benefits of COC use outweigh any theoretical risk of stroke, even in women with risk factors or in women who have migraine with aura. Progestin-only contraceptives do not alter one’s risk of stroke, unlike contraceptives that contain estrogen.

My bottom line

Can women with migraine headaches begin the use of combination hormonal methods? Yes, if there is no aura in their migraines and they are not older than age 35.

Can women with severe headaches that are nonmigrainous use combination hormonal methods? Possibly, but you should discontinue COCs if headache severity persists or worsens, using a 3-month time period for evaluation.

How do you manage women with migraines during the hormone-free interval? Consider the continuous method or shorten the hormone-free interval.

Recommendations for complicated patients. Consulting the CDC’s US MEC database7 can provide assistance in your care of more complicated patients requesting contraception. I also recommend the book, “Contraception for the Medically Challenging Patient,” edited by Rebecca Allen and Carrie Cwiak.10 It links nicely with the CDC guidelines and presents more detail on each subject.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The use of hormonal contraception in women with headaches, especially migraine headaches, is an important topic. Approximately 43% of women in the United States report migraines.1 Roughly the same percentage of reproductive-aged women use hormonal contraception.2 Data suggest that all migraineurs have some increased risk of stroke. Therefore, can women with migraine headaches use combination hormonal contraception? And can women with severe headaches that are nonmigrainous use combination hormonal contraception? Let’s examine available data to help us answer these questions.

Risk factors for stroke

Migraine without aura is the most common subset, but migraine with aura is more problematic relative to the increased incidence of stroke.1

A migraine aura is visual 90% of the time.1 Symptoms can include flickering lights, spots, zigzag lines, a sense of pins and needles, or dysphasic speech. Aura precedes the headache and usually resolves within 1 hour after the aura begins.

In addition to migraine headaches, risk factors for stroke include increasing age, hypertension, the use of combination oral contraceptives (COCs), the contraceptive patch and ring, and smoking.1

Data indicate that the risk for ischemic stroke is increased in women with migraines even without the presence of other risk factors. In a meta-analysis of 14 observational studies, the risk of ischemic stroke among all migraineurs was about 2-fold (relative risk [RR], 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9–2.5) compared with the risk of ischemic stroke in women of the same age group who did not have migraine headaches. When there is migraine without aura, it was slightly less than 2-fold (RR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–3.2). The risk of ischemic stroke among migraineurs with aura is increased more than 2 times compared with women without migraine (RR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.61–3.19).3 However, the absolute risk of ischemic stroke among reproductive-aged women is 11 per 100,000 women years.4

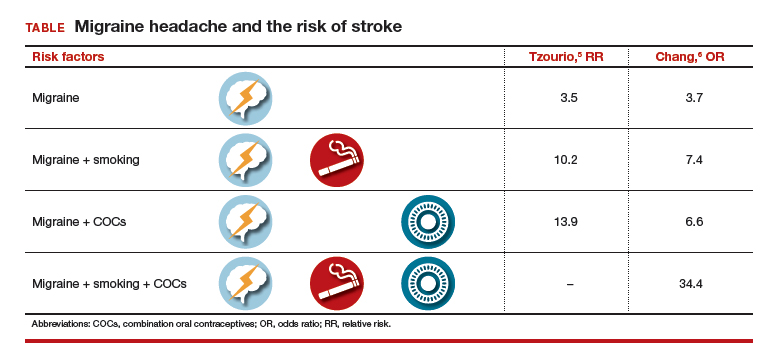

Two observational studies show how additional risk factors increase that risk (TABLE).5,6 There are similar trends in terms of overall risk of stroke among women with all types of migraine. However, when you add smoking as an additional risk factor for women with migraine headaches, there is a substantial increase in the risk of stroke. When a woman who has migraines uses COCs, there is increased risk varying from 2-fold to almost 4-fold. When you combine migraine, smoking, and COCs, a very, very large risk factor (odds ratio [OR], 34.4; 95% CI, 3.27–3.61) was reported by Chang and colleagues.6

Although these risks are impressive, it is important to keep in mind that even with a 10-fold increase, we are only talking about 1 case per 1,000 migraineurs.4 Unfortunately, stroke often leads to major disability and even death, such that any reduction in risk is still important.

Preventing estrogen withdrawal or menstrual migraines

How should we treat a woman who uses hormonal contraception and reports estrogen withdrawal or menstrual migraines? Based on clinical evidence, there are 2 ways to reduce her symptoms:

- COCs. Reduce the hormone-free interval by having her take COCs for 3 to 4 days instead of 7 days, or eliminate the hormone-free interval altogether by continuous use of COCs, usually 3 months at a time.7

- NSAIDs. For those who do not want to alter how they take their hormonal product, use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) starting 7 days before the onset of menses and continuing for 13 days. In a clinical trial by Sances and colleagues, this plan reduced the frequency, duration, and severity of menstrual migraines.8

Probably altering how she takes the COC would make the most sense for most individuals instead of taking NSAIDs for 75% of each month.

Recommendations from the US MEC

The US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers recommendations for contraceptive use9:

- For nonmigrainous headache, the CDC suggests that the benefits of using COCs outweigh the risks unless the headaches persist after 3 months of COC use.

- For migraine without aura, the benefits outweigh the risks in starting women who are younger than age 35 years on oral contraceptives. However, the risks of COCs outweigh the benefits in women who are age 35 years and older who develop migraine headache while on COCs, or who have risk factors for stroke.

- For migraine with aura, COCs are contraindicated.

- Progestin-only contraceptives. The CDC considers that the benefits of COC use outweigh any theoretical risk of stroke, even in women with risk factors or in women who have migraine with aura. Progestin-only contraceptives do not alter one’s risk of stroke, unlike contraceptives that contain estrogen.

My bottom line

Can women with migraine headaches begin the use of combination hormonal methods? Yes, if there is no aura in their migraines and they are not older than age 35.

Can women with severe headaches that are nonmigrainous use combination hormonal methods? Possibly, but you should discontinue COCs if headache severity persists or worsens, using a 3-month time period for evaluation.

How do you manage women with migraines during the hormone-free interval? Consider the continuous method or shorten the hormone-free interval.

Recommendations for complicated patients. Consulting the CDC’s US MEC database7 can provide assistance in your care of more complicated patients requesting contraception. I also recommend the book, “Contraception for the Medically Challenging Patient,” edited by Rebecca Allen and Carrie Cwiak.10 It links nicely with the CDC guidelines and presents more detail on each subject.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed MD, et al. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(11):1170–1178.

- Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):110–118.

- Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2005;330(7482):63–66.

- Petitti DB, Sydney S, Bernstein A, Wolf S, Quesenberry C, Ziel HK. Stoke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):8–15.

- Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglesias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310:830–833.

- Chang CL, Donaghy M, Poulter N. Migraine and stroke in young women: case-control study. The World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. BMJ. 1999;318(7175):13–18.

- Edelman A, Gallo MF, Nichols MD, Jensen JT, Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Continuous versus cyclic use of combined oral contraceptives for contraception: systematic Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(3):573–578.

- Sances G, Martignoni E, Fioroni L, Blandini F, Facchinetti F, Nappi G. Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache. 1990;30(11):705–709.

- US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1–86. https://www.cdc .gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2016.

- Allen RH, Cwiak CA, eds. Contraception for the medically challenging patient. New York, New York: Springer New York; 2014.

- Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed MD, et al. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(11):1170–1178.

- Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):110–118.

- Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2005;330(7482):63–66.

- Petitti DB, Sydney S, Bernstein A, Wolf S, Quesenberry C, Ziel HK. Stoke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):8–15.

- Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglesias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310:830–833.

- Chang CL, Donaghy M, Poulter N. Migraine and stroke in young women: case-control study. The World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. BMJ. 1999;318(7175):13–18.

- Edelman A, Gallo MF, Nichols MD, Jensen JT, Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Continuous versus cyclic use of combined oral contraceptives for contraception: systematic Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(3):573–578.

- Sances G, Martignoni E, Fioroni L, Blandini F, Facchinetti F, Nappi G. Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache. 1990;30(11):705–709.

- US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1–86. https://www.cdc .gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2016.

- Allen RH, Cwiak CA, eds. Contraception for the medically challenging patient. New York, New York: Springer New York; 2014.