User login

The VA National Formulary has existed since 1995. Before the development of a single national formulary, each VA facility managed its pharmacy benefit plan through its pharmacy and therapeutics committees. In other words, 173 formulary processes correlating with 173 facilities managed the pharmacy benefit across the entire VA system. This system served > 4 million veterans, providing > 108 million prescriptions per year.

Variations in provision of the pharmacy benefit were commonplace, including veteran access to drug therapy. Formulary processes for a particular drug that were already established in one facility might not have been developed in another facility. This variation among locations oftentimes limited drug availability. The purpose of developing a single National Formulary was twofold: (1) provide a uniform pharmacy benefit to all veterans by reducing variation in access to drugs among the facilities; and (2) obtain leverage in contract pricing for drugs across the entire VA system.

Pharmacy Benefits Management Capabilities

In 1995, VA Under Secretary for Health Kenneth Kizer,MD, established the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Services division. Pharmacy Benefits Management was assigned the tasks of developing a national formulary, creating pharmacologic guidelines, and managing drug costs and utilization. The VA Drug Product and Pharmaceuticals Management Division, based in Hines, Illinois, which already managed and monitored drug usage and purchasing for each VA Medical Center (VAMC) facility, expanded its services by hiring clinical pharmacists. These clinical pharmacists collaborated with field-based physicians to form the VA Medical Advisory Panel (MAP).

The VA Healthcare System is currently divided into 21 geographically defined VISN (Veteran Integrated System Network) regions. Each VISN has a designated VISN Pharmacist Executive (VPE), formerly known as a VISN Formulary Leader. The VPE serves as a pharmacy liaison between the VA health care facilities within the VISN and the national PBM. This collaboration allows open communication and a sharing of ideas and issues regarding drug therapy within the VA system. Collectively, this physician-pharmacist-based group became known as the Veterans Affairs Pharmacy Benefits Management Services division.

The National Acquisition Center (NAC) is another important collaborator with the PBM. Opportunities for pharmaceutical contracting are sought through the NAC. This contracting mechanism offers the VA opportunities for price reductions on bulk purchases, ready access to needed drugs, and a streamlined drug inventory process that reduces inventory management costs. In addition, with pharmaceutical contracting, the VA can provide identical drugs via multiple sources to minimize confusion for the patient. The NAC obtains optimized pricing through various techniques, such as competitive bidding among branded products within drug classes, the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) program, and performance-based incentive agreements. These techniques allow the VA to maintain stability with regard to average acquisition costs per 30-day-equivalent prescriptions.1,2

National PBM Clinical Program

The primary function of the National PBM Clinical Pharmacy Program Managers (NPBM-CPPMs) is to maintain the National Formulary. In addition, PBM functions to support VA field practitioners with promoting the safe and effective use of all medications, with the ultimate goal of helping veterans achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes.

The Clinical Program includes 12 NPBM-CPPMs. This group is composed of clinical pharmacists with advanced training and education in specialty therapeutic areas who serve as pharmaceutical subject matter experts within their specialty. It is the responsibility of this group to author drug monographs that summarize clinical data about the safety and efficacy of newly approved drugs (new molecular entities). These drug monographs serve as a tool to assist in determining the formulary status of a drug. The documents are evidence based and extensive, providing the necessary information for considerations related to formulary status.

A major role of the NPBM-CPPM group involves clinical document development, which is inclusive of the monograph-style documents used for formulary decision making. These clinical documents can be found stored on the PBM intranet sites, and most are under the Clinical Guidance subhead. Included among these documents are Drug Monographs used for formulary consideration, Criteria for Use (CFU), Abbreviated Reviews, Clinical Recommendations, and Drug Class Reviews. The various documents are designed to serve as resources for field practitioners to help optimize drug therapy for veterans.

The focus of the NPBM-CPPMs is to optimize pharmacotherapy from a population-based perspective. This focus is in contrast to the clinical pharmacy specialists who function at the facility level and focus primarily on patients in their particular geographic region. The NPBMCPPMs need to be familiar with the VA population as a whole. Although recognizing that every patient is different, NPBM-CPPMs develop clinical guidance documents that pertain to as many veterans as possible—typically about 80% of the population. About 20% of veterans may not possess the most common characteristics of an individual with a particular condition. If a common thread can be identified among this minority, then the focus of clinical guidance can expand to help improve the outcomes for this group, as well as educate VA providers.

Oncology NPBM-CPPMs

The field of oncology pharmacy has seen tremendous growth since it was originally recognized as a specialized field of pharmacy practice in 1998. At the same time, the FDA has approved many new drugs designated for oncologic conditions.3 This expansion of drugs has led to an increase in the NPBM-CPPMs oncology workforce, allowing the CPPMs to “divide and conquer” their responsibilities with respect to the oncologic diseases and pharmacotherapeutic agents used to treat these specific conditions.

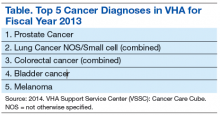

The FDA approval of an oncology drug means that an NPBM-CPPM needs to first determine the role and value of this drug to the veteran population. Knowing the most common oncologic conditions that afflict veterans helps to understand a drug’s importance to the VA. A number of common cancers among veterans include conditions associated with exposure to Agent Orange or other herbicides during military service and include chronic B-cell leukemias, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and prostate cancer.4 Aside from exposures related to military service, demographic and personal characteristics of the veteran population help determine the malignancies that put veterans at risk (eg, age and smoking history). It is apparent that colorectal cancer and lung cancer are among the most frequent tumor types detected among veterans.

Malignancies that are seen with less frequency in the VA are still important to the NPBM-CPPM. Breast cancer, for example, is a malignancy that afflicts a relatively small proportion of veterans, yet FDA-approved breast cancer drugs are reviewed for formulary consideration under the same national process.

Evidence-Based Determinations

The evidence-based drug monographs prepared for formulary consideration are approached in a consistent manner that takes into account clinical trial data published in peer-reviewed journals. In situations when peer-reviewed evidence is lacking, as in FDA-approval of a drug given Breakthrough Therapy designation, FDA Medical Review transcripts and abstracts from major meetings, such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), may be considered until published evidence is available.

The focus of the monograph is on efficacy and safety of the product and its potential impact on the veteran population. Cost-effective analyses are considered when available, although they are not commonplace at the time

of product launch.5 Authoritative reviews from other national public health providers (eg, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) are sought to provide a perspective on a drug therapy’s impact on other health care systems.

Criteria for Use documents are tools to help direct therapy to the appropriate veterans, emphasizing the considerations for safe and optimal use. Criteria for Use are not developed for every drug under review. Instead, CFUs are focused on only those drugs that may be considered a high risk for inappropriate use or may raise safety concerns. The documents developed by the NPBM-CPPM, whether they are monographs for formulary consideration or CFUs, undergo peer review by the Medical Advisory Panel (MAP), VISN VPEs, and fieldbased experts that include Field Advisory Committees (FACs) and other field practitioners.

Cost Issues

The stimulus to develop clinical guidance is not solely based on FDA approval of a new molecular entity. Many times, there are drug-related issues, identified by practitioners in the field, that call for resolution. Some of these issues are not exclusive to VA practice but impact VA practitioners just as they would impact non-VA practitioners. It is the role of the PBM to help address those drugrelated issues.

The high cost of oncology drugs is one such issue that impacts clinicians and patients both inside and outside the VA system. The Oncology FAC recognizes the impact of high-cost drugs on the VA system as a whole. They had been tasked with the goal of providing guidance to the field on the use of high-cost oncology drugs. The oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs has helped the Oncology FAC address this issue. The plan was to develop guidance documents that focus on minimizing the cost to both veterans and VA facilities. The strategy was to first develop

general, broad-based guidance documents that can be used by any site or VISN, especially those sites without oncology-trained pharmacists, to aid in making decisions about high-cost oncology drugs. The second step was to focus on the nuances of select drugs or diseases and provide drug-specific or disease-specific guidance to help manage cost issues within the identified areas.

Under the auspices of the Oncology FAC, the oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs convened the High Cost Oncology Drug Workgroup to help tackle this concern. The workgroup included oncology-specialized VA physicians and pharmacists who were divided into subgroups to address areas where recognition and subsequent intervention had the greatest potential to reduce facility drug expenditures.

These interventions previously have been identified as best practices within the VA and were thought to be applicable as broad-based guidance to serve as the first step of the cost control strategy. The work of the subgroups resulted in the following guidance documents:

- Dose Rounding in Oncology

- Oral Anticancer Drugs Dispensing and Monitoring

- Oral Anticancer Drugs: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring

- Chemotherapy Review Committee Process

- Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs

The Oncology FAC approved these guidance documents with subsequent review under the national PBM approval process. They are not mandatory for decision making but are encouraged for use at the facility or VISN level and can be found at the PBM website.

Clinical Pathways

Prostate cancer is one of the common malignancies that afflicts veterans. It is a disease with treatments involving multiple high-cost oncology drugs and as such is an ideal therapeutic area for possible intervention. Prostate cancer provides an opportunity for the second step of this project. As there are multiple therapies available for the treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that have been evaluated in the clinical trial setting for similar indications among comparable patient populations and are high cost items, providers find it difficult to choose among them.

A clinical pathway (CP) is a visual care map that provides direction for treatment options.6-8 Brief annotations are provided throughout the map to help provide rationale along with a rating of the clinical evidence that supports that decision. The ultimate goal of the CP is to improve patient outcomes by providing uniformity of care. Uniformity can lead to increased efficiencies, reduced chance of medication errors, and proactive management of expected toxicities. Clinical pathway development is an extensive process.

The oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs serve as facilitators for the development of the prostate cancer pathway. This involved the creation of a database of pertinent prostate cancer literature, including national consensus guidelines (ie, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Urology Association). This database is available for reference and discussion throughout the process. Key VA oncologists with expertise in prostate cancer management were identified to serve as stakeholders and critically review the literature, providing input regarding each step throughout the pathway process.

Similar to previously described documents, the CP for mCRPC (CP-mCRPC) will undergo peer review by the Oncology FAC with subsequent review under the national PBM approval process. The intent of the CPmCRPC is not to mandate decision making regarding treatment but to encourage consistent treatment and ultimately to minimize variance in practice and optimize patient outcomes. Clinical pathways are dependent on the current evidence and, therefore, are documents that require evaluation and regular updates. The CP process for prostate cancer

will serve as a model for the development of subsequent pathways for other diseases.

Prior Authorization

Many commercial insurers use prior authorization (PA) solely for drug coverage decision making. The PBM has recently adopted an expanded variation of the PA process for a few select medications at both the national and VISN level. The VA PBM PA is a thorough review process to ensure that select patients are appropriate for a particular therapy in an attempt to optimize outcomes. In the process, providing drug therapy to those veterans most likely to benefit will minimize the impact of drug cost.

Drugs selected for PA review are those that meet the following characteristics: (1) Drug has demonstrated limited clinical benefit in a select subpopulation of patients; (2) Drug has a high potential for off-label use; and (3) Drug is considered a high-cost item. The potential benefits of this process are not limited just to ensuring that the appropriate patient receives the appropriate therapy. Prior authorization at the national and VISN levels promotes consistent health care delivery throughout the VA.

Similar to the aforementioned CP process, consistency and minimization of variance in practice are desirable to improve veteran outcomes. As more experience is obtained with the PA process, its role within the VA will be reviewed and evaluated.

Conclusion

The task of addressing the high cost of today’s anticancer therapies is not one that can be addressed with a single initiative. The ASCO Cost of Care Task Force has been focusing on various initiatives that promote evidence-based decision making aimed at addressing the cost of cancer care.9 Consistent with this approach, the VA PBM division has been working with key stakeholders at the VISN and local levels to develop interventions aimed at optimizing therapeutic outcomes for the veteran.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Sales MM, Cunningham FE, Glassman PA, Valentino MA, Good CB. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration: 1995 to 2003. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(2):104-122.

2. Good CB, Valentino M. Access to affordable medications: The Department of Veterans Affairs pharmacy plan as a national model. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97(12):2129-2131.

3. CenterWatch. FDA approved drugs by therapeutic area. CenterWatch Website. http://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeuticarea/ 12/oncology. Accessed November 26, 2014.

4. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ disease associated with Agent Orange. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorang/conditions/index.asp. Last Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed November 26, 2014.

5. Aspinall SL, Good CB, Glassman PA, Valentino MA. The evolving use of cost-effectiveness analysis in formulary management within the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2005;43(suppl 7):20-26.

6. Panella M, Marchisio S, Di Stanislao F. Reducing clinical variations with clinical pathways: Do pathways work? Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(6):509-521.

7. Kinsman L, Rotter T, James E, Snow P, Willis J. What is a clinical pathway? Development of a definition to inform the debate. BMC Med. 2010;8:31.

8. Gesme DH, Wiseman M. Strategic use of clinical pathways. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):54-56.

9. Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3868-3874.

The VA National Formulary has existed since 1995. Before the development of a single national formulary, each VA facility managed its pharmacy benefit plan through its pharmacy and therapeutics committees. In other words, 173 formulary processes correlating with 173 facilities managed the pharmacy benefit across the entire VA system. This system served > 4 million veterans, providing > 108 million prescriptions per year.

Variations in provision of the pharmacy benefit were commonplace, including veteran access to drug therapy. Formulary processes for a particular drug that were already established in one facility might not have been developed in another facility. This variation among locations oftentimes limited drug availability. The purpose of developing a single National Formulary was twofold: (1) provide a uniform pharmacy benefit to all veterans by reducing variation in access to drugs among the facilities; and (2) obtain leverage in contract pricing for drugs across the entire VA system.

Pharmacy Benefits Management Capabilities

In 1995, VA Under Secretary for Health Kenneth Kizer,MD, established the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Services division. Pharmacy Benefits Management was assigned the tasks of developing a national formulary, creating pharmacologic guidelines, and managing drug costs and utilization. The VA Drug Product and Pharmaceuticals Management Division, based in Hines, Illinois, which already managed and monitored drug usage and purchasing for each VA Medical Center (VAMC) facility, expanded its services by hiring clinical pharmacists. These clinical pharmacists collaborated with field-based physicians to form the VA Medical Advisory Panel (MAP).

The VA Healthcare System is currently divided into 21 geographically defined VISN (Veteran Integrated System Network) regions. Each VISN has a designated VISN Pharmacist Executive (VPE), formerly known as a VISN Formulary Leader. The VPE serves as a pharmacy liaison between the VA health care facilities within the VISN and the national PBM. This collaboration allows open communication and a sharing of ideas and issues regarding drug therapy within the VA system. Collectively, this physician-pharmacist-based group became known as the Veterans Affairs Pharmacy Benefits Management Services division.

The National Acquisition Center (NAC) is another important collaborator with the PBM. Opportunities for pharmaceutical contracting are sought through the NAC. This contracting mechanism offers the VA opportunities for price reductions on bulk purchases, ready access to needed drugs, and a streamlined drug inventory process that reduces inventory management costs. In addition, with pharmaceutical contracting, the VA can provide identical drugs via multiple sources to minimize confusion for the patient. The NAC obtains optimized pricing through various techniques, such as competitive bidding among branded products within drug classes, the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) program, and performance-based incentive agreements. These techniques allow the VA to maintain stability with regard to average acquisition costs per 30-day-equivalent prescriptions.1,2

National PBM Clinical Program

The primary function of the National PBM Clinical Pharmacy Program Managers (NPBM-CPPMs) is to maintain the National Formulary. In addition, PBM functions to support VA field practitioners with promoting the safe and effective use of all medications, with the ultimate goal of helping veterans achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes.

The Clinical Program includes 12 NPBM-CPPMs. This group is composed of clinical pharmacists with advanced training and education in specialty therapeutic areas who serve as pharmaceutical subject matter experts within their specialty. It is the responsibility of this group to author drug monographs that summarize clinical data about the safety and efficacy of newly approved drugs (new molecular entities). These drug monographs serve as a tool to assist in determining the formulary status of a drug. The documents are evidence based and extensive, providing the necessary information for considerations related to formulary status.

A major role of the NPBM-CPPM group involves clinical document development, which is inclusive of the monograph-style documents used for formulary decision making. These clinical documents can be found stored on the PBM intranet sites, and most are under the Clinical Guidance subhead. Included among these documents are Drug Monographs used for formulary consideration, Criteria for Use (CFU), Abbreviated Reviews, Clinical Recommendations, and Drug Class Reviews. The various documents are designed to serve as resources for field practitioners to help optimize drug therapy for veterans.

The focus of the NPBM-CPPMs is to optimize pharmacotherapy from a population-based perspective. This focus is in contrast to the clinical pharmacy specialists who function at the facility level and focus primarily on patients in their particular geographic region. The NPBMCPPMs need to be familiar with the VA population as a whole. Although recognizing that every patient is different, NPBM-CPPMs develop clinical guidance documents that pertain to as many veterans as possible—typically about 80% of the population. About 20% of veterans may not possess the most common characteristics of an individual with a particular condition. If a common thread can be identified among this minority, then the focus of clinical guidance can expand to help improve the outcomes for this group, as well as educate VA providers.

Oncology NPBM-CPPMs

The field of oncology pharmacy has seen tremendous growth since it was originally recognized as a specialized field of pharmacy practice in 1998. At the same time, the FDA has approved many new drugs designated for oncologic conditions.3 This expansion of drugs has led to an increase in the NPBM-CPPMs oncology workforce, allowing the CPPMs to “divide and conquer” their responsibilities with respect to the oncologic diseases and pharmacotherapeutic agents used to treat these specific conditions.

The FDA approval of an oncology drug means that an NPBM-CPPM needs to first determine the role and value of this drug to the veteran population. Knowing the most common oncologic conditions that afflict veterans helps to understand a drug’s importance to the VA. A number of common cancers among veterans include conditions associated with exposure to Agent Orange or other herbicides during military service and include chronic B-cell leukemias, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and prostate cancer.4 Aside from exposures related to military service, demographic and personal characteristics of the veteran population help determine the malignancies that put veterans at risk (eg, age and smoking history). It is apparent that colorectal cancer and lung cancer are among the most frequent tumor types detected among veterans.

Malignancies that are seen with less frequency in the VA are still important to the NPBM-CPPM. Breast cancer, for example, is a malignancy that afflicts a relatively small proportion of veterans, yet FDA-approved breast cancer drugs are reviewed for formulary consideration under the same national process.

Evidence-Based Determinations

The evidence-based drug monographs prepared for formulary consideration are approached in a consistent manner that takes into account clinical trial data published in peer-reviewed journals. In situations when peer-reviewed evidence is lacking, as in FDA-approval of a drug given Breakthrough Therapy designation, FDA Medical Review transcripts and abstracts from major meetings, such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), may be considered until published evidence is available.

The focus of the monograph is on efficacy and safety of the product and its potential impact on the veteran population. Cost-effective analyses are considered when available, although they are not commonplace at the time

of product launch.5 Authoritative reviews from other national public health providers (eg, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) are sought to provide a perspective on a drug therapy’s impact on other health care systems.

Criteria for Use documents are tools to help direct therapy to the appropriate veterans, emphasizing the considerations for safe and optimal use. Criteria for Use are not developed for every drug under review. Instead, CFUs are focused on only those drugs that may be considered a high risk for inappropriate use or may raise safety concerns. The documents developed by the NPBM-CPPM, whether they are monographs for formulary consideration or CFUs, undergo peer review by the Medical Advisory Panel (MAP), VISN VPEs, and fieldbased experts that include Field Advisory Committees (FACs) and other field practitioners.

Cost Issues

The stimulus to develop clinical guidance is not solely based on FDA approval of a new molecular entity. Many times, there are drug-related issues, identified by practitioners in the field, that call for resolution. Some of these issues are not exclusive to VA practice but impact VA practitioners just as they would impact non-VA practitioners. It is the role of the PBM to help address those drugrelated issues.

The high cost of oncology drugs is one such issue that impacts clinicians and patients both inside and outside the VA system. The Oncology FAC recognizes the impact of high-cost drugs on the VA system as a whole. They had been tasked with the goal of providing guidance to the field on the use of high-cost oncology drugs. The oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs has helped the Oncology FAC address this issue. The plan was to develop guidance documents that focus on minimizing the cost to both veterans and VA facilities. The strategy was to first develop

general, broad-based guidance documents that can be used by any site or VISN, especially those sites without oncology-trained pharmacists, to aid in making decisions about high-cost oncology drugs. The second step was to focus on the nuances of select drugs or diseases and provide drug-specific or disease-specific guidance to help manage cost issues within the identified areas.

Under the auspices of the Oncology FAC, the oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs convened the High Cost Oncology Drug Workgroup to help tackle this concern. The workgroup included oncology-specialized VA physicians and pharmacists who were divided into subgroups to address areas where recognition and subsequent intervention had the greatest potential to reduce facility drug expenditures.

These interventions previously have been identified as best practices within the VA and were thought to be applicable as broad-based guidance to serve as the first step of the cost control strategy. The work of the subgroups resulted in the following guidance documents:

- Dose Rounding in Oncology

- Oral Anticancer Drugs Dispensing and Monitoring

- Oral Anticancer Drugs: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring

- Chemotherapy Review Committee Process

- Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs

The Oncology FAC approved these guidance documents with subsequent review under the national PBM approval process. They are not mandatory for decision making but are encouraged for use at the facility or VISN level and can be found at the PBM website.

Clinical Pathways

Prostate cancer is one of the common malignancies that afflicts veterans. It is a disease with treatments involving multiple high-cost oncology drugs and as such is an ideal therapeutic area for possible intervention. Prostate cancer provides an opportunity for the second step of this project. As there are multiple therapies available for the treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that have been evaluated in the clinical trial setting for similar indications among comparable patient populations and are high cost items, providers find it difficult to choose among them.

A clinical pathway (CP) is a visual care map that provides direction for treatment options.6-8 Brief annotations are provided throughout the map to help provide rationale along with a rating of the clinical evidence that supports that decision. The ultimate goal of the CP is to improve patient outcomes by providing uniformity of care. Uniformity can lead to increased efficiencies, reduced chance of medication errors, and proactive management of expected toxicities. Clinical pathway development is an extensive process.

The oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs serve as facilitators for the development of the prostate cancer pathway. This involved the creation of a database of pertinent prostate cancer literature, including national consensus guidelines (ie, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Urology Association). This database is available for reference and discussion throughout the process. Key VA oncologists with expertise in prostate cancer management were identified to serve as stakeholders and critically review the literature, providing input regarding each step throughout the pathway process.

Similar to previously described documents, the CP for mCRPC (CP-mCRPC) will undergo peer review by the Oncology FAC with subsequent review under the national PBM approval process. The intent of the CPmCRPC is not to mandate decision making regarding treatment but to encourage consistent treatment and ultimately to minimize variance in practice and optimize patient outcomes. Clinical pathways are dependent on the current evidence and, therefore, are documents that require evaluation and regular updates. The CP process for prostate cancer

will serve as a model for the development of subsequent pathways for other diseases.

Prior Authorization

Many commercial insurers use prior authorization (PA) solely for drug coverage decision making. The PBM has recently adopted an expanded variation of the PA process for a few select medications at both the national and VISN level. The VA PBM PA is a thorough review process to ensure that select patients are appropriate for a particular therapy in an attempt to optimize outcomes. In the process, providing drug therapy to those veterans most likely to benefit will minimize the impact of drug cost.

Drugs selected for PA review are those that meet the following characteristics: (1) Drug has demonstrated limited clinical benefit in a select subpopulation of patients; (2) Drug has a high potential for off-label use; and (3) Drug is considered a high-cost item. The potential benefits of this process are not limited just to ensuring that the appropriate patient receives the appropriate therapy. Prior authorization at the national and VISN levels promotes consistent health care delivery throughout the VA.

Similar to the aforementioned CP process, consistency and minimization of variance in practice are desirable to improve veteran outcomes. As more experience is obtained with the PA process, its role within the VA will be reviewed and evaluated.

Conclusion

The task of addressing the high cost of today’s anticancer therapies is not one that can be addressed with a single initiative. The ASCO Cost of Care Task Force has been focusing on various initiatives that promote evidence-based decision making aimed at addressing the cost of cancer care.9 Consistent with this approach, the VA PBM division has been working with key stakeholders at the VISN and local levels to develop interventions aimed at optimizing therapeutic outcomes for the veteran.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The VA National Formulary has existed since 1995. Before the development of a single national formulary, each VA facility managed its pharmacy benefit plan through its pharmacy and therapeutics committees. In other words, 173 formulary processes correlating with 173 facilities managed the pharmacy benefit across the entire VA system. This system served > 4 million veterans, providing > 108 million prescriptions per year.

Variations in provision of the pharmacy benefit were commonplace, including veteran access to drug therapy. Formulary processes for a particular drug that were already established in one facility might not have been developed in another facility. This variation among locations oftentimes limited drug availability. The purpose of developing a single National Formulary was twofold: (1) provide a uniform pharmacy benefit to all veterans by reducing variation in access to drugs among the facilities; and (2) obtain leverage in contract pricing for drugs across the entire VA system.

Pharmacy Benefits Management Capabilities

In 1995, VA Under Secretary for Health Kenneth Kizer,MD, established the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Services division. Pharmacy Benefits Management was assigned the tasks of developing a national formulary, creating pharmacologic guidelines, and managing drug costs and utilization. The VA Drug Product and Pharmaceuticals Management Division, based in Hines, Illinois, which already managed and monitored drug usage and purchasing for each VA Medical Center (VAMC) facility, expanded its services by hiring clinical pharmacists. These clinical pharmacists collaborated with field-based physicians to form the VA Medical Advisory Panel (MAP).

The VA Healthcare System is currently divided into 21 geographically defined VISN (Veteran Integrated System Network) regions. Each VISN has a designated VISN Pharmacist Executive (VPE), formerly known as a VISN Formulary Leader. The VPE serves as a pharmacy liaison between the VA health care facilities within the VISN and the national PBM. This collaboration allows open communication and a sharing of ideas and issues regarding drug therapy within the VA system. Collectively, this physician-pharmacist-based group became known as the Veterans Affairs Pharmacy Benefits Management Services division.

The National Acquisition Center (NAC) is another important collaborator with the PBM. Opportunities for pharmaceutical contracting are sought through the NAC. This contracting mechanism offers the VA opportunities for price reductions on bulk purchases, ready access to needed drugs, and a streamlined drug inventory process that reduces inventory management costs. In addition, with pharmaceutical contracting, the VA can provide identical drugs via multiple sources to minimize confusion for the patient. The NAC obtains optimized pricing through various techniques, such as competitive bidding among branded products within drug classes, the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) program, and performance-based incentive agreements. These techniques allow the VA to maintain stability with regard to average acquisition costs per 30-day-equivalent prescriptions.1,2

National PBM Clinical Program

The primary function of the National PBM Clinical Pharmacy Program Managers (NPBM-CPPMs) is to maintain the National Formulary. In addition, PBM functions to support VA field practitioners with promoting the safe and effective use of all medications, with the ultimate goal of helping veterans achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes.

The Clinical Program includes 12 NPBM-CPPMs. This group is composed of clinical pharmacists with advanced training and education in specialty therapeutic areas who serve as pharmaceutical subject matter experts within their specialty. It is the responsibility of this group to author drug monographs that summarize clinical data about the safety and efficacy of newly approved drugs (new molecular entities). These drug monographs serve as a tool to assist in determining the formulary status of a drug. The documents are evidence based and extensive, providing the necessary information for considerations related to formulary status.

A major role of the NPBM-CPPM group involves clinical document development, which is inclusive of the monograph-style documents used for formulary decision making. These clinical documents can be found stored on the PBM intranet sites, and most are under the Clinical Guidance subhead. Included among these documents are Drug Monographs used for formulary consideration, Criteria for Use (CFU), Abbreviated Reviews, Clinical Recommendations, and Drug Class Reviews. The various documents are designed to serve as resources for field practitioners to help optimize drug therapy for veterans.

The focus of the NPBM-CPPMs is to optimize pharmacotherapy from a population-based perspective. This focus is in contrast to the clinical pharmacy specialists who function at the facility level and focus primarily on patients in their particular geographic region. The NPBMCPPMs need to be familiar with the VA population as a whole. Although recognizing that every patient is different, NPBM-CPPMs develop clinical guidance documents that pertain to as many veterans as possible—typically about 80% of the population. About 20% of veterans may not possess the most common characteristics of an individual with a particular condition. If a common thread can be identified among this minority, then the focus of clinical guidance can expand to help improve the outcomes for this group, as well as educate VA providers.

Oncology NPBM-CPPMs

The field of oncology pharmacy has seen tremendous growth since it was originally recognized as a specialized field of pharmacy practice in 1998. At the same time, the FDA has approved many new drugs designated for oncologic conditions.3 This expansion of drugs has led to an increase in the NPBM-CPPMs oncology workforce, allowing the CPPMs to “divide and conquer” their responsibilities with respect to the oncologic diseases and pharmacotherapeutic agents used to treat these specific conditions.

The FDA approval of an oncology drug means that an NPBM-CPPM needs to first determine the role and value of this drug to the veteran population. Knowing the most common oncologic conditions that afflict veterans helps to understand a drug’s importance to the VA. A number of common cancers among veterans include conditions associated with exposure to Agent Orange or other herbicides during military service and include chronic B-cell leukemias, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and prostate cancer.4 Aside from exposures related to military service, demographic and personal characteristics of the veteran population help determine the malignancies that put veterans at risk (eg, age and smoking history). It is apparent that colorectal cancer and lung cancer are among the most frequent tumor types detected among veterans.

Malignancies that are seen with less frequency in the VA are still important to the NPBM-CPPM. Breast cancer, for example, is a malignancy that afflicts a relatively small proportion of veterans, yet FDA-approved breast cancer drugs are reviewed for formulary consideration under the same national process.

Evidence-Based Determinations

The evidence-based drug monographs prepared for formulary consideration are approached in a consistent manner that takes into account clinical trial data published in peer-reviewed journals. In situations when peer-reviewed evidence is lacking, as in FDA-approval of a drug given Breakthrough Therapy designation, FDA Medical Review transcripts and abstracts from major meetings, such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), may be considered until published evidence is available.

The focus of the monograph is on efficacy and safety of the product and its potential impact on the veteran population. Cost-effective analyses are considered when available, although they are not commonplace at the time

of product launch.5 Authoritative reviews from other national public health providers (eg, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) are sought to provide a perspective on a drug therapy’s impact on other health care systems.

Criteria for Use documents are tools to help direct therapy to the appropriate veterans, emphasizing the considerations for safe and optimal use. Criteria for Use are not developed for every drug under review. Instead, CFUs are focused on only those drugs that may be considered a high risk for inappropriate use or may raise safety concerns. The documents developed by the NPBM-CPPM, whether they are monographs for formulary consideration or CFUs, undergo peer review by the Medical Advisory Panel (MAP), VISN VPEs, and fieldbased experts that include Field Advisory Committees (FACs) and other field practitioners.

Cost Issues

The stimulus to develop clinical guidance is not solely based on FDA approval of a new molecular entity. Many times, there are drug-related issues, identified by practitioners in the field, that call for resolution. Some of these issues are not exclusive to VA practice but impact VA practitioners just as they would impact non-VA practitioners. It is the role of the PBM to help address those drugrelated issues.

The high cost of oncology drugs is one such issue that impacts clinicians and patients both inside and outside the VA system. The Oncology FAC recognizes the impact of high-cost drugs on the VA system as a whole. They had been tasked with the goal of providing guidance to the field on the use of high-cost oncology drugs. The oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs has helped the Oncology FAC address this issue. The plan was to develop guidance documents that focus on minimizing the cost to both veterans and VA facilities. The strategy was to first develop

general, broad-based guidance documents that can be used by any site or VISN, especially those sites without oncology-trained pharmacists, to aid in making decisions about high-cost oncology drugs. The second step was to focus on the nuances of select drugs or diseases and provide drug-specific or disease-specific guidance to help manage cost issues within the identified areas.

Under the auspices of the Oncology FAC, the oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs convened the High Cost Oncology Drug Workgroup to help tackle this concern. The workgroup included oncology-specialized VA physicians and pharmacists who were divided into subgroups to address areas where recognition and subsequent intervention had the greatest potential to reduce facility drug expenditures.

These interventions previously have been identified as best practices within the VA and were thought to be applicable as broad-based guidance to serve as the first step of the cost control strategy. The work of the subgroups resulted in the following guidance documents:

- Dose Rounding in Oncology

- Oral Anticancer Drugs Dispensing and Monitoring

- Oral Anticancer Drugs: Recommended Dispensing and Monitoring

- Chemotherapy Review Committee Process

- Determining Clinical Benefit of High Cost Oncology Drugs

The Oncology FAC approved these guidance documents with subsequent review under the national PBM approval process. They are not mandatory for decision making but are encouraged for use at the facility or VISN level and can be found at the PBM website.

Clinical Pathways

Prostate cancer is one of the common malignancies that afflicts veterans. It is a disease with treatments involving multiple high-cost oncology drugs and as such is an ideal therapeutic area for possible intervention. Prostate cancer provides an opportunity for the second step of this project. As there are multiple therapies available for the treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that have been evaluated in the clinical trial setting for similar indications among comparable patient populations and are high cost items, providers find it difficult to choose among them.

A clinical pathway (CP) is a visual care map that provides direction for treatment options.6-8 Brief annotations are provided throughout the map to help provide rationale along with a rating of the clinical evidence that supports that decision. The ultimate goal of the CP is to improve patient outcomes by providing uniformity of care. Uniformity can lead to increased efficiencies, reduced chance of medication errors, and proactive management of expected toxicities. Clinical pathway development is an extensive process.

The oncology-focused NPBM-CPPMs serve as facilitators for the development of the prostate cancer pathway. This involved the creation of a database of pertinent prostate cancer literature, including national consensus guidelines (ie, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Urology Association). This database is available for reference and discussion throughout the process. Key VA oncologists with expertise in prostate cancer management were identified to serve as stakeholders and critically review the literature, providing input regarding each step throughout the pathway process.

Similar to previously described documents, the CP for mCRPC (CP-mCRPC) will undergo peer review by the Oncology FAC with subsequent review under the national PBM approval process. The intent of the CPmCRPC is not to mandate decision making regarding treatment but to encourage consistent treatment and ultimately to minimize variance in practice and optimize patient outcomes. Clinical pathways are dependent on the current evidence and, therefore, are documents that require evaluation and regular updates. The CP process for prostate cancer

will serve as a model for the development of subsequent pathways for other diseases.

Prior Authorization

Many commercial insurers use prior authorization (PA) solely for drug coverage decision making. The PBM has recently adopted an expanded variation of the PA process for a few select medications at both the national and VISN level. The VA PBM PA is a thorough review process to ensure that select patients are appropriate for a particular therapy in an attempt to optimize outcomes. In the process, providing drug therapy to those veterans most likely to benefit will minimize the impact of drug cost.

Drugs selected for PA review are those that meet the following characteristics: (1) Drug has demonstrated limited clinical benefit in a select subpopulation of patients; (2) Drug has a high potential for off-label use; and (3) Drug is considered a high-cost item. The potential benefits of this process are not limited just to ensuring that the appropriate patient receives the appropriate therapy. Prior authorization at the national and VISN levels promotes consistent health care delivery throughout the VA.

Similar to the aforementioned CP process, consistency and minimization of variance in practice are desirable to improve veteran outcomes. As more experience is obtained with the PA process, its role within the VA will be reviewed and evaluated.

Conclusion

The task of addressing the high cost of today’s anticancer therapies is not one that can be addressed with a single initiative. The ASCO Cost of Care Task Force has been focusing on various initiatives that promote evidence-based decision making aimed at addressing the cost of cancer care.9 Consistent with this approach, the VA PBM division has been working with key stakeholders at the VISN and local levels to develop interventions aimed at optimizing therapeutic outcomes for the veteran.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Sales MM, Cunningham FE, Glassman PA, Valentino MA, Good CB. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration: 1995 to 2003. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(2):104-122.

2. Good CB, Valentino M. Access to affordable medications: The Department of Veterans Affairs pharmacy plan as a national model. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97(12):2129-2131.

3. CenterWatch. FDA approved drugs by therapeutic area. CenterWatch Website. http://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeuticarea/ 12/oncology. Accessed November 26, 2014.

4. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ disease associated with Agent Orange. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorang/conditions/index.asp. Last Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed November 26, 2014.

5. Aspinall SL, Good CB, Glassman PA, Valentino MA. The evolving use of cost-effectiveness analysis in formulary management within the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2005;43(suppl 7):20-26.

6. Panella M, Marchisio S, Di Stanislao F. Reducing clinical variations with clinical pathways: Do pathways work? Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(6):509-521.

7. Kinsman L, Rotter T, James E, Snow P, Willis J. What is a clinical pathway? Development of a definition to inform the debate. BMC Med. 2010;8:31.

8. Gesme DH, Wiseman M. Strategic use of clinical pathways. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):54-56.

9. Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3868-3874.

1. Sales MM, Cunningham FE, Glassman PA, Valentino MA, Good CB. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration: 1995 to 2003. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(2):104-122.

2. Good CB, Valentino M. Access to affordable medications: The Department of Veterans Affairs pharmacy plan as a national model. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97(12):2129-2131.

3. CenterWatch. FDA approved drugs by therapeutic area. CenterWatch Website. http://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeuticarea/ 12/oncology. Accessed November 26, 2014.

4. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ disease associated with Agent Orange. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorang/conditions/index.asp. Last Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed November 26, 2014.

5. Aspinall SL, Good CB, Glassman PA, Valentino MA. The evolving use of cost-effectiveness analysis in formulary management within the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2005;43(suppl 7):20-26.

6. Panella M, Marchisio S, Di Stanislao F. Reducing clinical variations with clinical pathways: Do pathways work? Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(6):509-521.

7. Kinsman L, Rotter T, James E, Snow P, Willis J. What is a clinical pathway? Development of a definition to inform the debate. BMC Med. 2010;8:31.

8. Gesme DH, Wiseman M. Strategic use of clinical pathways. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):54-56.

9. Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3868-3874.