User login

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is a neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. At least two thirds of cases of dementia in people ≥ 65 years of age are due to AD, making it the most common type of dementia. At present, there is no cure for AD, which is associated with a long preclinical stage and a progressive disease course. In the United States, AD is the sixth leading cause of death.

Individuals with AD develop amyloid plaques in the hippocampus and in other areas of the cerebral cortex. The symptoms of AD vary depending on the stage of the disease; however, in most patients with late-onset AD (≥ 65 years of age), the most common presenting symptom is episodic short-term memory loss, with relative sparing of long-term memory. Subsequently, patients may experience impairments in problem-solving, judgment, executive functioning, motivation, and organization. It is not uncommon for individuals with AD to lack insight into the impairments they are experiences, or even to deny deficits.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy, social withdrawal, disinhibition, agitation, psychosis, and wandering are common in the mid- to late stages of the disease. Patients may also experience difficulty performing learned motor tasks (dyspraxia), olfactory dysfunction, and sleep disturbances; develop extrapyramidal motor signs (eg, dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonian symptoms) followed by difficulties with primitive reflexes and incontinence, and may ultimately become totally dependent on caregivers.

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for the diagnosis of AD. Because some patients may lack insight into their disease, it is vital to elicit a history from the patient's family and caregivers as well. Onset and early symptoms are important to note to aid in differentiating AD from other types of dementia. In most patients with late-onset AD, comprehensive clinical assessment can provide reasonable diagnostic certainty. This should include a detailed neurologic examination to rule out other conditions; most patients with AD will have a normal neurologic exam.

A mental status examination to evaluate concentration, attention, recent and remote memory, language, visuospatial functioning, praxis, and executive functioning should also be conducted. Brief standard examinations, such the Mini-Mental State Examination, can be used for initial screening purposes, although they are less sensitive and specific than more comprehensive tests. Follow-up visits for patients diagnosed with AD should therefore include a full mental status examination to gauge disease progression as well as the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

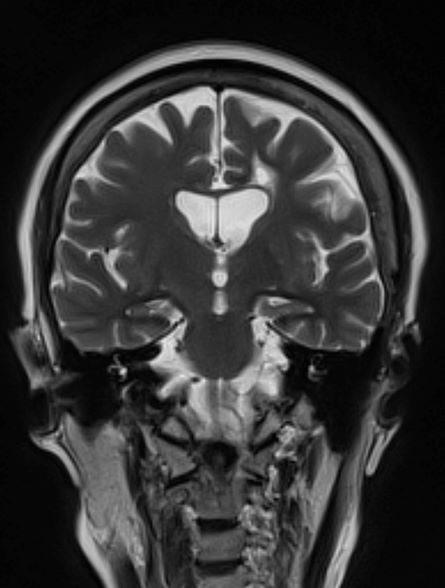

Brain imaging can be beneficial both for diagnosing AD and monitoring the disease's clinical course. MRI or CT of the brain can help eliminate alternate causes of dementia, such as stroke or tumors, from consideration. Dilated lateral ventricles and widened cortical sulci, particularly in the temporal area, are typical findings in AD.

The standard medical treatment for AD includes cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist. Both US and European guidelines list ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, tacrine) as first-line pharmacotherapies for mild to moderate AD; however, these agents only show modest efficacy on cognitive deficits and nonsignificant efficacy on functional capacity in mild to moderate AD. Memantine, a partial NMDA antagonist, shows very limited efficacy on cognitive symptoms, with no improvement in functional domains. Newly approved anti-amyloid therapies include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may help to mitigate the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders. Behavioral interventions (eg, patient-centered approaches and caregiver training) may be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD and are often combined with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise also be beneficial for brain health and delaying disease progression.

Numerous novel agents are under investigation for AD, including anti-tau therapy, anti-neuroinflammatory therapy, neuroprotective agents (such as NMDA receptor modulators), and brain stimulation.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is a neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. At least two thirds of cases of dementia in people ≥ 65 years of age are due to AD, making it the most common type of dementia. At present, there is no cure for AD, which is associated with a long preclinical stage and a progressive disease course. In the United States, AD is the sixth leading cause of death.

Individuals with AD develop amyloid plaques in the hippocampus and in other areas of the cerebral cortex. The symptoms of AD vary depending on the stage of the disease; however, in most patients with late-onset AD (≥ 65 years of age), the most common presenting symptom is episodic short-term memory loss, with relative sparing of long-term memory. Subsequently, patients may experience impairments in problem-solving, judgment, executive functioning, motivation, and organization. It is not uncommon for individuals with AD to lack insight into the impairments they are experiences, or even to deny deficits.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy, social withdrawal, disinhibition, agitation, psychosis, and wandering are common in the mid- to late stages of the disease. Patients may also experience difficulty performing learned motor tasks (dyspraxia), olfactory dysfunction, and sleep disturbances; develop extrapyramidal motor signs (eg, dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonian symptoms) followed by difficulties with primitive reflexes and incontinence, and may ultimately become totally dependent on caregivers.

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for the diagnosis of AD. Because some patients may lack insight into their disease, it is vital to elicit a history from the patient's family and caregivers as well. Onset and early symptoms are important to note to aid in differentiating AD from other types of dementia. In most patients with late-onset AD, comprehensive clinical assessment can provide reasonable diagnostic certainty. This should include a detailed neurologic examination to rule out other conditions; most patients with AD will have a normal neurologic exam.

A mental status examination to evaluate concentration, attention, recent and remote memory, language, visuospatial functioning, praxis, and executive functioning should also be conducted. Brief standard examinations, such the Mini-Mental State Examination, can be used for initial screening purposes, although they are less sensitive and specific than more comprehensive tests. Follow-up visits for patients diagnosed with AD should therefore include a full mental status examination to gauge disease progression as well as the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Brain imaging can be beneficial both for diagnosing AD and monitoring the disease's clinical course. MRI or CT of the brain can help eliminate alternate causes of dementia, such as stroke or tumors, from consideration. Dilated lateral ventricles and widened cortical sulci, particularly in the temporal area, are typical findings in AD.

The standard medical treatment for AD includes cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist. Both US and European guidelines list ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, tacrine) as first-line pharmacotherapies for mild to moderate AD; however, these agents only show modest efficacy on cognitive deficits and nonsignificant efficacy on functional capacity in mild to moderate AD. Memantine, a partial NMDA antagonist, shows very limited efficacy on cognitive symptoms, with no improvement in functional domains. Newly approved anti-amyloid therapies include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may help to mitigate the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders. Behavioral interventions (eg, patient-centered approaches and caregiver training) may be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD and are often combined with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise also be beneficial for brain health and delaying disease progression.

Numerous novel agents are under investigation for AD, including anti-tau therapy, anti-neuroinflammatory therapy, neuroprotective agents (such as NMDA receptor modulators), and brain stimulation.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is a neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. At least two thirds of cases of dementia in people ≥ 65 years of age are due to AD, making it the most common type of dementia. At present, there is no cure for AD, which is associated with a long preclinical stage and a progressive disease course. In the United States, AD is the sixth leading cause of death.

Individuals with AD develop amyloid plaques in the hippocampus and in other areas of the cerebral cortex. The symptoms of AD vary depending on the stage of the disease; however, in most patients with late-onset AD (≥ 65 years of age), the most common presenting symptom is episodic short-term memory loss, with relative sparing of long-term memory. Subsequently, patients may experience impairments in problem-solving, judgment, executive functioning, motivation, and organization. It is not uncommon for individuals with AD to lack insight into the impairments they are experiences, or even to deny deficits.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy, social withdrawal, disinhibition, agitation, psychosis, and wandering are common in the mid- to late stages of the disease. Patients may also experience difficulty performing learned motor tasks (dyspraxia), olfactory dysfunction, and sleep disturbances; develop extrapyramidal motor signs (eg, dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonian symptoms) followed by difficulties with primitive reflexes and incontinence, and may ultimately become totally dependent on caregivers.

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for the diagnosis of AD. Because some patients may lack insight into their disease, it is vital to elicit a history from the patient's family and caregivers as well. Onset and early symptoms are important to note to aid in differentiating AD from other types of dementia. In most patients with late-onset AD, comprehensive clinical assessment can provide reasonable diagnostic certainty. This should include a detailed neurologic examination to rule out other conditions; most patients with AD will have a normal neurologic exam.

A mental status examination to evaluate concentration, attention, recent and remote memory, language, visuospatial functioning, praxis, and executive functioning should also be conducted. Brief standard examinations, such the Mini-Mental State Examination, can be used for initial screening purposes, although they are less sensitive and specific than more comprehensive tests. Follow-up visits for patients diagnosed with AD should therefore include a full mental status examination to gauge disease progression as well as the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Brain imaging can be beneficial both for diagnosing AD and monitoring the disease's clinical course. MRI or CT of the brain can help eliminate alternate causes of dementia, such as stroke or tumors, from consideration. Dilated lateral ventricles and widened cortical sulci, particularly in the temporal area, are typical findings in AD.

The standard medical treatment for AD includes cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist. Both US and European guidelines list ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, tacrine) as first-line pharmacotherapies for mild to moderate AD; however, these agents only show modest efficacy on cognitive deficits and nonsignificant efficacy on functional capacity in mild to moderate AD. Memantine, a partial NMDA antagonist, shows very limited efficacy on cognitive symptoms, with no improvement in functional domains. Newly approved anti-amyloid therapies include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may help to mitigate the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders. Behavioral interventions (eg, patient-centered approaches and caregiver training) may be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD and are often combined with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise also be beneficial for brain health and delaying disease progression.

Numerous novel agents are under investigation for AD, including anti-tau therapy, anti-neuroinflammatory therapy, neuroprotective agents (such as NMDA receptor modulators), and brain stimulation.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 79-year-old man presents to his primary care provider (PCP) for an annual examination. The patient is accompanied by his oldest daughter, with whom he has lived since the death of his spouse approximately 9 months earlier. During the examination, the patient's daughter expresses concern about her father's cognitive functioning. Specifically, she has observed him becoming increasingly forgetful since he moved in with her. She states he has repeatedly forgotten the names of her dogs and has forgotten food in the microwave or on the stove on several occasions. Recently, after leaving a restaurant, her father was unable to remember where he had parked his car, and she suspects he has gotten lost while driving to and from familiar places several times. When questioned, the patient denies impairment and states occasional memory loss is "just part of the aging process."

Neither the patient nor his daughter reports any difficulties with his ability to groom and dress himself. His medical history is notable for high cholesterol, which is managed with a statin. The patient is a former smoker (24 pack-years) and occasionally drinks alcohol. His current height and weight are 5 ft 11 in and 177 lb, respectively.

The patient appears well nourished and oriented to time and place, although he appears to have moderate difficulty hearing and questions sometimes need to be repeated to him. His blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are all within normal ranges. The patient scores 16 on the Mini-Mental State Examination. His PCP orders MRI, which reveals atrophy on both hippocampi.