User login

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2011 there were 25.8 million people in the United States living with diabetes mellitus (DM), 90% to 95% of whom had type 2 DM.1 Seven million of those with DM are undiagnosed. In addition, an estimated 79 million adults in the United States have prediabetes, a condition in which glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels are above normal but do not yet meet the diagnostic threshold for DM (≥6.5%).1 This large population with prediabetes, defined by HbA1c levels of 5.7% to 6.4%, has a 5-year risk of progression to diabetes ranging from 9% to 50%; the higher risk is associated with higher HbA1c levels as the disease represents a continuum.2

The benefits of diagnosis and treatment of diabetes—preventing the progression of microvascular complications—are well established. Through medication, exercise, and dietary interventions, the progression of both prediabetes and diabetes can be halted and in many cases reversed.

Given the prevalence of DM in the United States and the clear benefits of treatment, the ability to diagnose DM is important for any physician who may encounter patients with undiagnosed diabetes or prediabetes. This article reviews the management of hyperglycemia relevant to the emergency physician (EP) and discusses the criteria used in diagnosing DM.

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) currently does not have a clinical policy for the initial treatment of patients with DM that is newly diagnosed in the ED. A 2007 survey of 152 EPs in the United States found that 52% would leave initiation of outpatient treatment of diabetes to a patient’s primary care physician (PCP), regardless of the degree of hyperglycemia noted in the ED.3 Almost paradoxically, among these same EPs, the most common reason for not screening for diabetes (cited by 69%) was the inability to secure follow-up for newly diagnosed patients. Given the fragmentary care many emergency patients receive and the difficulty in assuring close ED follow-up, reviewing the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for initiation of diabetes management is worthwhile.

ADA Treatment Guidelines

Metformin

Metformin, if tolerated and without contraindications, is the preferred initial pharmacologic agent for all patients with newly diagnosed DM. This drug typically lowers HbA1c by 1.5%, and does not cause weight gain or hypoglycemia associated with some other oral agents (eg, sulfonylureas). Metformin therapy, however, is contraindicated in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Cr >1.5 in males and >1.4 in females), liver disease, a history of lactic acidosis, and a low-perfusion state. Metformin also should not be used for 48 hours following an intravenous (IV) contrast-enhanced study.

When starting metformin or increasing the dose, patients frequently experience abdominal symptoms, including cramping, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These side effects are usually mild and self-limiting, and they usually resolve within a week. However, patients should be warned of these complications and advised to take metformin with meals to limit side effects. They also should be encouraged to continue the medication through the initial symptoms, if possible.

For a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 DM, a reasonable ED discharge plan is to start metformin at 500 mg daily, taken with a meal. If the patient develops abdominal symptoms, the dose can be reduced to 250 mg daily. Patients should additionally be advised to follow up with their PCP as soon as feasible. Patients can be instructed to increase the dose of metformin on their own. Because the development of gastrointestinal symptoms is the main dose-limiting effect of metformin therapy, it is generally safe to give patients instructions on weekly dose escalation by 500 mg/day to the optimal dose of 1,000 mg twice daily. Although metformin therapy is associated with rare cases of lactic acidosis in patients with CKD, it does not, on its own, cause acute kidney injury; therefore, intense monitoring is not required while doses are increased. Metformin therapy can decrease vitamin B12 absorption, though it rarely results in megaloblastic anemia, and it takes 5 to 10 years for neurological symptoms to manifest.5

Other Treatment Options

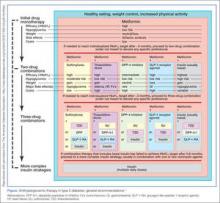

The Figure highlights the ADA guidelines on additional pharmacologic agents beyond metformin. When these additional agents are used, the patient should follow-up with a PCP every 3 months to determine how far HbA1c has been lowered. For most patients with DM, the goal for HbA1c is less than 7%. This goal may be raised for elderly patients and those with a history of cardiovascular disease, as these patients are at higher risk for cardiovascular mortality from an episode of hypoglycemia.

The secondary medication options include sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and insulin. Insulin therapy is the final medication step for all patients with DM who are willing and able to comply with daily injections and who have failed to meet goals through alternative agents.

Before using additional agents beyond metformin, the PCP or endocrinologist should discuss in detail factors such as side effects (ie, weight gain, risk of hypoglycemia), medication delivery (GLP-1 agonists and insulin require injections), and cost with the patient. It is generally advisable not to try to accomplish this medication adjustment in the ED without consultation with a PCP or endocrinologist.

Diagnosis

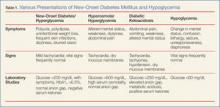

The clinical presentation of new-onset DM can range from the relatively benign (eg, polyuria, polydipsia, frequent skin infections) to the life-threatening (eg, diabetic ketoacidosis) (Table 1). The classic symptoms of hyperglycemia include polyuria, polydipsia, unexplained weight loss, easy fatigability, dizziness, and blurred vision. Any one of these symptoms should prompt consideration of DM in the differential diagnosis.

Four abnormal laboratory results comprise the ADA’s diagnostic criteria for DM6:

- HbA1c ≥6.5%;

- 8-hour fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL;

- 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥200 mg/dL (Patient is given 75 g sugar orally; then plasma glucose is drawn 2 hours later); and

- A random plasma glucose of ≥200 mg/dL in association with “classic symptoms” of DM, defined as polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss.

In the absence of an unequivocal indicator, such as the patient presenting in diabetic ketoacidosis, the formal diagnosis of DM should not be made unless at least 2 abnormal test results are obtained simultaneously (from a 2-hour OGTT test and an HbA1c panel, for example, or when the same test is repeated one month later and both test results indicate DM).

Limitations of Glucometers

When interpreting test results, keep in mind that the US Food and Drug Administration allows point-of-care (POC) glucometers to have an accuracy of +/- 20%. The POC glucometers measure whole-blood glucose rather than plasma glucose; generally the amount of glucose in plasma is about 10% to 15% higher than the amount in whole blood.7 Therefore, the formal diagnosis of DM relies on laboratory plasma glucose results; POC glucometer results may guide the EP in initiating a workup for DM but should not be among the diagnostic criteria.

HbA1c Testing

The HbA1c percentage represents the preceding 3-month average plasma glucose level. This is due to nonenzymatic glycosylation of Hb, a reaction driven by higher concentrations of circulating plasma glucose. The HbA1c can be falsely low in states of high red blood cell (RBC) turnover, such as ongoing blood loss or the RBC fragility seen in hemoglobinopathies. Patients who have had RBC transfusions in the preceding months will have inaccurate HbA1c test results as well.

Keeping these test characteristics in mind, the HbA1c test may be more useful than glucose-based testing strategies in diagnosing diabetes in the ED. Hyperglycemia can be observed in nondiabetic emergency patients undergoing a stress response, since gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis are normal hepatic stress responses to circulating epinephrine and cortisol. Unless a patient is on chronic steroids, the HbA1c is not similarly affected.

A recent study of ED patients using HbA1c as the sole screening modality found that test characteristics for ED patients were similar to those for patients in typical outpatient settings. HbA1c of 6.5 or greater yielded a sensitivity of 54% and a specificity of 96% in diagnosing diabetes.8 The availability of test results at the time of the emergency visit depends upon the individual hospital laboratory, but most labs run the test itself in less than an hour. Emergency physicians working in hospitals that perform the test will often have the test results prior to patient discharge.

Inpatient Management

Managing a patient with newly diagnosed DM that requires admission to the hospital is different from managing a patient who can be treated as an outpatient. The ADA-recommended treatment regimen for DM in the inpatient setting focuses on the use of insulin. While type 1 DM, by definition, requires insulin treatment, many patients with type 2 DM are treated with oral agents only as outpatients. However, because of complications associated with the use of oral agents in low renal perfusion states (such as during surgery, during IV contrast-enhanced studies, or when the admitting condition causes shock), the ADA generally does not prefer oral agents for inpatient glycemic control. Metformin particularly should not be used in the inpatient setting, due to increased risk of lactic acidosis.

The preferred insulin regimen for noncritically ill diabetic inpatients consists of scheduled subcutaneous therapy with basal, nutritional, and correctional components.9 Because absorption from subcutaneous tissue varies among critically ill patients, the ADA recommends an IV insulin therapy protocol for ICU patients with diabetes. The NICE SUGAR trial found that the overall risk of death was 2.6% higher among patients treated with an intensive insulin therapy regimen (finger stick blood glucose goal 80-108 mg/dL) than it was among patients treated using standard therapy with a goal of less than 180 mg/dL, a statistically significant difference.10 These results form the basis for the ADA-recommended inpatient glycemic target of 140 to 180 mg/dL among critically ill patients.11 While no definitive evidence exists to guide glycemic control among noncritically ill inpatients, the strategy applied to critically ill patients can be extrapolated to other hospitalized patients because the ADA recommends treatment to keep finger stick blood glucose values below 180 mg/dL.

Hypoglycemia

Often a hypoglycemic event can clearly be correlated to a missed meal. This may only require re-education of the patient about the need to be consistent in the timing of his or her dietary regimen. However, often a hypoglycemic event is not clearly related to a missed meal. When a patient has recently taken a long-acting insulin or sulfonylurea or has new renal failure, prolonged observation or admission may be required. In most other cases of medication-induced hypoglycemia, the patients are expediently sent home. As many such patient encounters occur in the early morning hours, EPs need to know how to manage insulin regimens if these patients are to be safely discharged home. Additionally, worsening renal function is a common cause of potentiation of both oral agents and insulin; it is generally worthwhile to check renal function on patients presenting with significant hypoglycemia.

After a significant hypoglycemic event, many guidelines recommend decreasing the daily insulin dose by 10% to 20%. However, with a careful medication history and knowledge of each insulin dose’s activity profile, a physician can often discern which individual insulin dose is responsible for a given hypoglycemic event. That individual daily dose can then be decreased by 20% to better target the cause of the hypoglycemic event.

Conclusion

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic medical conditions in the United States, and more than 7 million Americans may be living with undiagnosed DM. In the ED setting, physicians regularly encounter patients with undiagnosed type 2 DM. Since treatment is known to prevent the microvascular complications associated with DM, EPs should know the diagnostic criteria and understand the ADA’s inpatient and outpatient treatment recommendations.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

- Zhang X, Gregg EW, Williamson DF, et al. A1C level and future risk of diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1665-1673.

- Ginde AA, Delaney KE, Pallin DJ, Camargo CA Jr. Multicenter survey of emergency physician management and referral for hyperglycemia. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(2):264-270.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); EuropeanAssociation for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes:a patient-centered approach. Position statementf the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364-1379.

- Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):359-367.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S81-S90.

- Kotwal N, Pandit A. Variability of capillary blood glucose monitoring measured on home glucose monitoring devices. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S248-S251.

- Silverman RA, Thakker U, Ellman T, et al. Hemoglobin A1c as a screen for previously undiagnosed prediabetes and diabetes in an acute-care setting. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):1908-1912.

- American Diabetes Association Executive Summary: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Supp 1):S5-S13.

- Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, et al; NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283-1297.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14-S80.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2011 there were 25.8 million people in the United States living with diabetes mellitus (DM), 90% to 95% of whom had type 2 DM.1 Seven million of those with DM are undiagnosed. In addition, an estimated 79 million adults in the United States have prediabetes, a condition in which glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels are above normal but do not yet meet the diagnostic threshold for DM (≥6.5%).1 This large population with prediabetes, defined by HbA1c levels of 5.7% to 6.4%, has a 5-year risk of progression to diabetes ranging from 9% to 50%; the higher risk is associated with higher HbA1c levels as the disease represents a continuum.2

The benefits of diagnosis and treatment of diabetes—preventing the progression of microvascular complications—are well established. Through medication, exercise, and dietary interventions, the progression of both prediabetes and diabetes can be halted and in many cases reversed.

Given the prevalence of DM in the United States and the clear benefits of treatment, the ability to diagnose DM is important for any physician who may encounter patients with undiagnosed diabetes or prediabetes. This article reviews the management of hyperglycemia relevant to the emergency physician (EP) and discusses the criteria used in diagnosing DM.

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) currently does not have a clinical policy for the initial treatment of patients with DM that is newly diagnosed in the ED. A 2007 survey of 152 EPs in the United States found that 52% would leave initiation of outpatient treatment of diabetes to a patient’s primary care physician (PCP), regardless of the degree of hyperglycemia noted in the ED.3 Almost paradoxically, among these same EPs, the most common reason for not screening for diabetes (cited by 69%) was the inability to secure follow-up for newly diagnosed patients. Given the fragmentary care many emergency patients receive and the difficulty in assuring close ED follow-up, reviewing the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for initiation of diabetes management is worthwhile.

ADA Treatment Guidelines

Metformin

Metformin, if tolerated and without contraindications, is the preferred initial pharmacologic agent for all patients with newly diagnosed DM. This drug typically lowers HbA1c by 1.5%, and does not cause weight gain or hypoglycemia associated with some other oral agents (eg, sulfonylureas). Metformin therapy, however, is contraindicated in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Cr >1.5 in males and >1.4 in females), liver disease, a history of lactic acidosis, and a low-perfusion state. Metformin also should not be used for 48 hours following an intravenous (IV) contrast-enhanced study.

When starting metformin or increasing the dose, patients frequently experience abdominal symptoms, including cramping, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These side effects are usually mild and self-limiting, and they usually resolve within a week. However, patients should be warned of these complications and advised to take metformin with meals to limit side effects. They also should be encouraged to continue the medication through the initial symptoms, if possible.

For a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 DM, a reasonable ED discharge plan is to start metformin at 500 mg daily, taken with a meal. If the patient develops abdominal symptoms, the dose can be reduced to 250 mg daily. Patients should additionally be advised to follow up with their PCP as soon as feasible. Patients can be instructed to increase the dose of metformin on their own. Because the development of gastrointestinal symptoms is the main dose-limiting effect of metformin therapy, it is generally safe to give patients instructions on weekly dose escalation by 500 mg/day to the optimal dose of 1,000 mg twice daily. Although metformin therapy is associated with rare cases of lactic acidosis in patients with CKD, it does not, on its own, cause acute kidney injury; therefore, intense monitoring is not required while doses are increased. Metformin therapy can decrease vitamin B12 absorption, though it rarely results in megaloblastic anemia, and it takes 5 to 10 years for neurological symptoms to manifest.5

Other Treatment Options

The Figure highlights the ADA guidelines on additional pharmacologic agents beyond metformin. When these additional agents are used, the patient should follow-up with a PCP every 3 months to determine how far HbA1c has been lowered. For most patients with DM, the goal for HbA1c is less than 7%. This goal may be raised for elderly patients and those with a history of cardiovascular disease, as these patients are at higher risk for cardiovascular mortality from an episode of hypoglycemia.

The secondary medication options include sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and insulin. Insulin therapy is the final medication step for all patients with DM who are willing and able to comply with daily injections and who have failed to meet goals through alternative agents.

Before using additional agents beyond metformin, the PCP or endocrinologist should discuss in detail factors such as side effects (ie, weight gain, risk of hypoglycemia), medication delivery (GLP-1 agonists and insulin require injections), and cost with the patient. It is generally advisable not to try to accomplish this medication adjustment in the ED without consultation with a PCP or endocrinologist.

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of new-onset DM can range from the relatively benign (eg, polyuria, polydipsia, frequent skin infections) to the life-threatening (eg, diabetic ketoacidosis) (Table 1). The classic symptoms of hyperglycemia include polyuria, polydipsia, unexplained weight loss, easy fatigability, dizziness, and blurred vision. Any one of these symptoms should prompt consideration of DM in the differential diagnosis.

Four abnormal laboratory results comprise the ADA’s diagnostic criteria for DM6:

- HbA1c ≥6.5%;

- 8-hour fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL;

- 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥200 mg/dL (Patient is given 75 g sugar orally; then plasma glucose is drawn 2 hours later); and

- A random plasma glucose of ≥200 mg/dL in association with “classic symptoms” of DM, defined as polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss.

In the absence of an unequivocal indicator, such as the patient presenting in diabetic ketoacidosis, the formal diagnosis of DM should not be made unless at least 2 abnormal test results are obtained simultaneously (from a 2-hour OGTT test and an HbA1c panel, for example, or when the same test is repeated one month later and both test results indicate DM).

Limitations of Glucometers

When interpreting test results, keep in mind that the US Food and Drug Administration allows point-of-care (POC) glucometers to have an accuracy of +/- 20%. The POC glucometers measure whole-blood glucose rather than plasma glucose; generally the amount of glucose in plasma is about 10% to 15% higher than the amount in whole blood.7 Therefore, the formal diagnosis of DM relies on laboratory plasma glucose results; POC glucometer results may guide the EP in initiating a workup for DM but should not be among the diagnostic criteria.

HbA1c Testing

The HbA1c percentage represents the preceding 3-month average plasma glucose level. This is due to nonenzymatic glycosylation of Hb, a reaction driven by higher concentrations of circulating plasma glucose. The HbA1c can be falsely low in states of high red blood cell (RBC) turnover, such as ongoing blood loss or the RBC fragility seen in hemoglobinopathies. Patients who have had RBC transfusions in the preceding months will have inaccurate HbA1c test results as well.

Keeping these test characteristics in mind, the HbA1c test may be more useful than glucose-based testing strategies in diagnosing diabetes in the ED. Hyperglycemia can be observed in nondiabetic emergency patients undergoing a stress response, since gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis are normal hepatic stress responses to circulating epinephrine and cortisol. Unless a patient is on chronic steroids, the HbA1c is not similarly affected.

A recent study of ED patients using HbA1c as the sole screening modality found that test characteristics for ED patients were similar to those for patients in typical outpatient settings. HbA1c of 6.5 or greater yielded a sensitivity of 54% and a specificity of 96% in diagnosing diabetes.8 The availability of test results at the time of the emergency visit depends upon the individual hospital laboratory, but most labs run the test itself in less than an hour. Emergency physicians working in hospitals that perform the test will often have the test results prior to patient discharge.

Inpatient Management

Managing a patient with newly diagnosed DM that requires admission to the hospital is different from managing a patient who can be treated as an outpatient. The ADA-recommended treatment regimen for DM in the inpatient setting focuses on the use of insulin. While type 1 DM, by definition, requires insulin treatment, many patients with type 2 DM are treated with oral agents only as outpatients. However, because of complications associated with the use of oral agents in low renal perfusion states (such as during surgery, during IV contrast-enhanced studies, or when the admitting condition causes shock), the ADA generally does not prefer oral agents for inpatient glycemic control. Metformin particularly should not be used in the inpatient setting, due to increased risk of lactic acidosis.

The preferred insulin regimen for noncritically ill diabetic inpatients consists of scheduled subcutaneous therapy with basal, nutritional, and correctional components.9 Because absorption from subcutaneous tissue varies among critically ill patients, the ADA recommends an IV insulin therapy protocol for ICU patients with diabetes. The NICE SUGAR trial found that the overall risk of death was 2.6% higher among patients treated with an intensive insulin therapy regimen (finger stick blood glucose goal 80-108 mg/dL) than it was among patients treated using standard therapy with a goal of less than 180 mg/dL, a statistically significant difference.10 These results form the basis for the ADA-recommended inpatient glycemic target of 140 to 180 mg/dL among critically ill patients.11 While no definitive evidence exists to guide glycemic control among noncritically ill inpatients, the strategy applied to critically ill patients can be extrapolated to other hospitalized patients because the ADA recommends treatment to keep finger stick blood glucose values below 180 mg/dL.

Hypoglycemia

Often a hypoglycemic event can clearly be correlated to a missed meal. This may only require re-education of the patient about the need to be consistent in the timing of his or her dietary regimen. However, often a hypoglycemic event is not clearly related to a missed meal. When a patient has recently taken a long-acting insulin or sulfonylurea or has new renal failure, prolonged observation or admission may be required. In most other cases of medication-induced hypoglycemia, the patients are expediently sent home. As many such patient encounters occur in the early morning hours, EPs need to know how to manage insulin regimens if these patients are to be safely discharged home. Additionally, worsening renal function is a common cause of potentiation of both oral agents and insulin; it is generally worthwhile to check renal function on patients presenting with significant hypoglycemia.

After a significant hypoglycemic event, many guidelines recommend decreasing the daily insulin dose by 10% to 20%. However, with a careful medication history and knowledge of each insulin dose’s activity profile, a physician can often discern which individual insulin dose is responsible for a given hypoglycemic event. That individual daily dose can then be decreased by 20% to better target the cause of the hypoglycemic event.

Conclusion

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic medical conditions in the United States, and more than 7 million Americans may be living with undiagnosed DM. In the ED setting, physicians regularly encounter patients with undiagnosed type 2 DM. Since treatment is known to prevent the microvascular complications associated with DM, EPs should know the diagnostic criteria and understand the ADA’s inpatient and outpatient treatment recommendations.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2011 there were 25.8 million people in the United States living with diabetes mellitus (DM), 90% to 95% of whom had type 2 DM.1 Seven million of those with DM are undiagnosed. In addition, an estimated 79 million adults in the United States have prediabetes, a condition in which glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels are above normal but do not yet meet the diagnostic threshold for DM (≥6.5%).1 This large population with prediabetes, defined by HbA1c levels of 5.7% to 6.4%, has a 5-year risk of progression to diabetes ranging from 9% to 50%; the higher risk is associated with higher HbA1c levels as the disease represents a continuum.2

The benefits of diagnosis and treatment of diabetes—preventing the progression of microvascular complications—are well established. Through medication, exercise, and dietary interventions, the progression of both prediabetes and diabetes can be halted and in many cases reversed.

Given the prevalence of DM in the United States and the clear benefits of treatment, the ability to diagnose DM is important for any physician who may encounter patients with undiagnosed diabetes or prediabetes. This article reviews the management of hyperglycemia relevant to the emergency physician (EP) and discusses the criteria used in diagnosing DM.

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) currently does not have a clinical policy for the initial treatment of patients with DM that is newly diagnosed in the ED. A 2007 survey of 152 EPs in the United States found that 52% would leave initiation of outpatient treatment of diabetes to a patient’s primary care physician (PCP), regardless of the degree of hyperglycemia noted in the ED.3 Almost paradoxically, among these same EPs, the most common reason for not screening for diabetes (cited by 69%) was the inability to secure follow-up for newly diagnosed patients. Given the fragmentary care many emergency patients receive and the difficulty in assuring close ED follow-up, reviewing the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for initiation of diabetes management is worthwhile.

ADA Treatment Guidelines

Metformin

Metformin, if tolerated and without contraindications, is the preferred initial pharmacologic agent for all patients with newly diagnosed DM. This drug typically lowers HbA1c by 1.5%, and does not cause weight gain or hypoglycemia associated with some other oral agents (eg, sulfonylureas). Metformin therapy, however, is contraindicated in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Cr >1.5 in males and >1.4 in females), liver disease, a history of lactic acidosis, and a low-perfusion state. Metformin also should not be used for 48 hours following an intravenous (IV) contrast-enhanced study.

When starting metformin or increasing the dose, patients frequently experience abdominal symptoms, including cramping, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These side effects are usually mild and self-limiting, and they usually resolve within a week. However, patients should be warned of these complications and advised to take metformin with meals to limit side effects. They also should be encouraged to continue the medication through the initial symptoms, if possible.

For a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 DM, a reasonable ED discharge plan is to start metformin at 500 mg daily, taken with a meal. If the patient develops abdominal symptoms, the dose can be reduced to 250 mg daily. Patients should additionally be advised to follow up with their PCP as soon as feasible. Patients can be instructed to increase the dose of metformin on their own. Because the development of gastrointestinal symptoms is the main dose-limiting effect of metformin therapy, it is generally safe to give patients instructions on weekly dose escalation by 500 mg/day to the optimal dose of 1,000 mg twice daily. Although metformin therapy is associated with rare cases of lactic acidosis in patients with CKD, it does not, on its own, cause acute kidney injury; therefore, intense monitoring is not required while doses are increased. Metformin therapy can decrease vitamin B12 absorption, though it rarely results in megaloblastic anemia, and it takes 5 to 10 years for neurological symptoms to manifest.5

Other Treatment Options

The Figure highlights the ADA guidelines on additional pharmacologic agents beyond metformin. When these additional agents are used, the patient should follow-up with a PCP every 3 months to determine how far HbA1c has been lowered. For most patients with DM, the goal for HbA1c is less than 7%. This goal may be raised for elderly patients and those with a history of cardiovascular disease, as these patients are at higher risk for cardiovascular mortality from an episode of hypoglycemia.

The secondary medication options include sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and insulin. Insulin therapy is the final medication step for all patients with DM who are willing and able to comply with daily injections and who have failed to meet goals through alternative agents.

Before using additional agents beyond metformin, the PCP or endocrinologist should discuss in detail factors such as side effects (ie, weight gain, risk of hypoglycemia), medication delivery (GLP-1 agonists and insulin require injections), and cost with the patient. It is generally advisable not to try to accomplish this medication adjustment in the ED without consultation with a PCP or endocrinologist.

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of new-onset DM can range from the relatively benign (eg, polyuria, polydipsia, frequent skin infections) to the life-threatening (eg, diabetic ketoacidosis) (Table 1). The classic symptoms of hyperglycemia include polyuria, polydipsia, unexplained weight loss, easy fatigability, dizziness, and blurred vision. Any one of these symptoms should prompt consideration of DM in the differential diagnosis.

Four abnormal laboratory results comprise the ADA’s diagnostic criteria for DM6:

- HbA1c ≥6.5%;

- 8-hour fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL;

- 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥200 mg/dL (Patient is given 75 g sugar orally; then plasma glucose is drawn 2 hours later); and

- A random plasma glucose of ≥200 mg/dL in association with “classic symptoms” of DM, defined as polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss.

In the absence of an unequivocal indicator, such as the patient presenting in diabetic ketoacidosis, the formal diagnosis of DM should not be made unless at least 2 abnormal test results are obtained simultaneously (from a 2-hour OGTT test and an HbA1c panel, for example, or when the same test is repeated one month later and both test results indicate DM).

Limitations of Glucometers

When interpreting test results, keep in mind that the US Food and Drug Administration allows point-of-care (POC) glucometers to have an accuracy of +/- 20%. The POC glucometers measure whole-blood glucose rather than plasma glucose; generally the amount of glucose in plasma is about 10% to 15% higher than the amount in whole blood.7 Therefore, the formal diagnosis of DM relies on laboratory plasma glucose results; POC glucometer results may guide the EP in initiating a workup for DM but should not be among the diagnostic criteria.

HbA1c Testing

The HbA1c percentage represents the preceding 3-month average plasma glucose level. This is due to nonenzymatic glycosylation of Hb, a reaction driven by higher concentrations of circulating plasma glucose. The HbA1c can be falsely low in states of high red blood cell (RBC) turnover, such as ongoing blood loss or the RBC fragility seen in hemoglobinopathies. Patients who have had RBC transfusions in the preceding months will have inaccurate HbA1c test results as well.

Keeping these test characteristics in mind, the HbA1c test may be more useful than glucose-based testing strategies in diagnosing diabetes in the ED. Hyperglycemia can be observed in nondiabetic emergency patients undergoing a stress response, since gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis are normal hepatic stress responses to circulating epinephrine and cortisol. Unless a patient is on chronic steroids, the HbA1c is not similarly affected.

A recent study of ED patients using HbA1c as the sole screening modality found that test characteristics for ED patients were similar to those for patients in typical outpatient settings. HbA1c of 6.5 or greater yielded a sensitivity of 54% and a specificity of 96% in diagnosing diabetes.8 The availability of test results at the time of the emergency visit depends upon the individual hospital laboratory, but most labs run the test itself in less than an hour. Emergency physicians working in hospitals that perform the test will often have the test results prior to patient discharge.

Inpatient Management

Managing a patient with newly diagnosed DM that requires admission to the hospital is different from managing a patient who can be treated as an outpatient. The ADA-recommended treatment regimen for DM in the inpatient setting focuses on the use of insulin. While type 1 DM, by definition, requires insulin treatment, many patients with type 2 DM are treated with oral agents only as outpatients. However, because of complications associated with the use of oral agents in low renal perfusion states (such as during surgery, during IV contrast-enhanced studies, or when the admitting condition causes shock), the ADA generally does not prefer oral agents for inpatient glycemic control. Metformin particularly should not be used in the inpatient setting, due to increased risk of lactic acidosis.

The preferred insulin regimen for noncritically ill diabetic inpatients consists of scheduled subcutaneous therapy with basal, nutritional, and correctional components.9 Because absorption from subcutaneous tissue varies among critically ill patients, the ADA recommends an IV insulin therapy protocol for ICU patients with diabetes. The NICE SUGAR trial found that the overall risk of death was 2.6% higher among patients treated with an intensive insulin therapy regimen (finger stick blood glucose goal 80-108 mg/dL) than it was among patients treated using standard therapy with a goal of less than 180 mg/dL, a statistically significant difference.10 These results form the basis for the ADA-recommended inpatient glycemic target of 140 to 180 mg/dL among critically ill patients.11 While no definitive evidence exists to guide glycemic control among noncritically ill inpatients, the strategy applied to critically ill patients can be extrapolated to other hospitalized patients because the ADA recommends treatment to keep finger stick blood glucose values below 180 mg/dL.

Hypoglycemia

Often a hypoglycemic event can clearly be correlated to a missed meal. This may only require re-education of the patient about the need to be consistent in the timing of his or her dietary regimen. However, often a hypoglycemic event is not clearly related to a missed meal. When a patient has recently taken a long-acting insulin or sulfonylurea or has new renal failure, prolonged observation or admission may be required. In most other cases of medication-induced hypoglycemia, the patients are expediently sent home. As many such patient encounters occur in the early morning hours, EPs need to know how to manage insulin regimens if these patients are to be safely discharged home. Additionally, worsening renal function is a common cause of potentiation of both oral agents and insulin; it is generally worthwhile to check renal function on patients presenting with significant hypoglycemia.

After a significant hypoglycemic event, many guidelines recommend decreasing the daily insulin dose by 10% to 20%. However, with a careful medication history and knowledge of each insulin dose’s activity profile, a physician can often discern which individual insulin dose is responsible for a given hypoglycemic event. That individual daily dose can then be decreased by 20% to better target the cause of the hypoglycemic event.

Conclusion

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic medical conditions in the United States, and more than 7 million Americans may be living with undiagnosed DM. In the ED setting, physicians regularly encounter patients with undiagnosed type 2 DM. Since treatment is known to prevent the microvascular complications associated with DM, EPs should know the diagnostic criteria and understand the ADA’s inpatient and outpatient treatment recommendations.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

- Zhang X, Gregg EW, Williamson DF, et al. A1C level and future risk of diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1665-1673.

- Ginde AA, Delaney KE, Pallin DJ, Camargo CA Jr. Multicenter survey of emergency physician management and referral for hyperglycemia. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(2):264-270.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); EuropeanAssociation for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes:a patient-centered approach. Position statementf the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364-1379.

- Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):359-367.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S81-S90.

- Kotwal N, Pandit A. Variability of capillary blood glucose monitoring measured on home glucose monitoring devices. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S248-S251.

- Silverman RA, Thakker U, Ellman T, et al. Hemoglobin A1c as a screen for previously undiagnosed prediabetes and diabetes in an acute-care setting. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):1908-1912.

- American Diabetes Association Executive Summary: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Supp 1):S5-S13.

- Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, et al; NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283-1297.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14-S80.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

- Zhang X, Gregg EW, Williamson DF, et al. A1C level and future risk of diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1665-1673.

- Ginde AA, Delaney KE, Pallin DJ, Camargo CA Jr. Multicenter survey of emergency physician management and referral for hyperglycemia. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(2):264-270.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); EuropeanAssociation for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes:a patient-centered approach. Position statementf the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364-1379.

- Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):359-367.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S81-S90.

- Kotwal N, Pandit A. Variability of capillary blood glucose monitoring measured on home glucose monitoring devices. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S248-S251.

- Silverman RA, Thakker U, Ellman T, et al. Hemoglobin A1c as a screen for previously undiagnosed prediabetes and diabetes in an acute-care setting. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):1908-1912.

- American Diabetes Association Executive Summary: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Supp 1):S5-S13.

- Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, et al; NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283-1297.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14-S80.