User login

In the United States, nearly 50 million legal abortions were performed between 1973 and 2008.1 About half of pregnancies in American women are unintended, and 4 out of 10 unintended pregnancies are terminated by abortion.2 Of the women who had abortions, 54% had used a contraceptive method during the month they became pregnant.3

It is hoped that the expanded use of emergency contraception will translate into fewer abortions. However, in a 2006–2008 survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only 9.7% of women ages 15 to 44 reported ever having used emergency contraception.4 (To put this figure in perspective, a similar number—about 10%—of women in this age group become pregnant in any given year, half of them unintentionally.4) Clearly, patients need to be better educated in the methods of contraception and emergency contraception.

Hospitals are not meeting the need. Pretending to be in need of emergency contraception, Harrison5 called the emergency departments of all 597 Catholic hospitals in the United States and 615 (17%) of the non-Catholic hospitals. About half of the staff she spoke to said they do not dispense emergency contraception, even in cases of sexual assault. This was the case for both Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals. Of the people she talked to who said they did not provide emergency contraception under any circumstance, only about half gave her a phone number for another facility to try, and most of these phone numbers were wrong, were for facilities that were not open on weekends, or were for facilities that did not offer emergency contraception either. This is in spite of legal precedent, which indicates that failure to provide complete post-rape counseling, including emergency contraception, constitutes inadequate care and gives a woman the standing to sue the hospital.6

Clearly, better provider education is also needed in the area of emergency contraception. The Association of Reproductive Health Professionals has a helpful Web site for providers and for patients. In addition to up-to-date information about contraceptive and emergency contraceptive choices, it provides advice on how to discuss emergency contraception with patients (www.arhp.org). We can test our own knowledge of this topic by reviewing the following questions.

WHICH PRODUCT IS MOST EFFECTIVE?

Q: True or false? Levonorgestrel monotherapy (Plan B One-Step, Next Choice) is the most effective oral emergency contraceptive.

A: False, although this statement was true before the US approval of ulipristal acetate (ella) in August 2010.

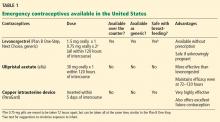

For many years levonorgestrel monotherapy has been the mainstay of emergency contraception, having replaced the combination estrogen-progestin (Yuzpe) regimen because of better tolerability and improved efficacy.7 Its main mechanism of action involves delaying ovulation. Levonorgestrel is given in two doses of 0.75 mg 12 hours apart, or as a single 1.5-mg dose (Table 1). Both formulations of levonorgestrel are available over the counter to women age 17 and older, or by prescription if they are under age 17.

However, a randomized controlled trial showed that women treated with ulipristal had about half the number of pregnancies than in those treated with levonorgestrel, with pregnancy rates of 0.9% vs 1.7%.8

HOW WIDE IS THE WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY?

Q: True or false? Both ulipristal and levonorgestrel can be taken up to 120 hours (5 days) after unprotected intercourse. However, ulipristal maintains its effectiveness throughout this time, whereas levonorgestrel becomes less effective the longer a patient waits to take it.

A: True. Ulipristal is a second-generation selective progesterone receptor modulator. These drugs can function as agonists, antagonists, or mixed agonist-antagonists at the progesterone receptor, depending on the tissue affected. Ulipristal is given as a one-time, 30-mg dose within 120 hours of intercourse.

In a study of 1,696 women, 844 of whom received ulipristal acetate and 852 of whom received levonorgestrel, ulipristal was at least as effective as levonorgestrel when used within 72 hours of intercourse for emergency contraception, with 15 pregnancies in the ulipristal group and 22 pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group (odds ratio [OR] 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35–1.31]). However, ulipristal prevented significantly more pregnancies than levonorgestrel at 72 to 120 hours, with no pregnancies in the ulipristal group and three pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group.9

Because ulipristal has a long half-life (32 hours), it can delay ovulation beyond the life span of sperm, thereby extending the window of opportunity for emergency contraception. However, patients should be advised to avoid further unprotected intercourse after the use of emergency contraception. Because emergency contraception works mainly by delaying ovulation, it may increase the likelihood of pregnancy if the patient has unprotected intercourse again several days later.

IS MIFEPRISTONE AN EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTIVE?

Q: True or false? In the United States, mifepristone (Mifeprex), also known as RU-486, is available for use as an emergency contraceptive in addition to its use in abortion.

A: False, even though mifepristone, another selective progesterone receptor modulator, is highly effective when used up to 120 hours after intercourse. In fact, it might be effective up to 17 days after unprotected intercourse.10

Although mifepristone is one of the most effective forms of emergency contraception, social and political controversy has prevented its approval in the United States. However, it is approved for use as an abortifacient, at a higher dose than would be used for emergency contraception.

Unlike levonorgestrel, mifepristone exerts its effect via two potential mechanisms: delaying ovulation and preventing implantation.11

IUDs AS EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

Q: True or false? Insertion of a 5-year intrauterine device (IUD), ie, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena), is 99.8% effective at preventing pregnancy when used within 5 days of unprotected intercourse.

A: False. The Mirena IUD has not been studied as a form of emergency contraception. However, this statement would be true for the 10-year copper IUD ParaGard. Copper-releasing IUDs are considered a very effective method of emergency contraception, with associated pregnancy rates of 0.0% to 0.2% when inserted up until implantation (within 5 days after ovulation).12,13 If desired, the IUD can then be kept in place for up to 10 years as a method of birth control.

However, this method requires the ready availability of a health professional trained to do the insertion. It is also important to make sure that the patient will not be at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections from further unprotected intercourse. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that an IUD be placed within 5 days of unprotected intercourse for use as emergency contraception.

A recent review looked at 42 published studies of copper IUDs used for emergency contraception around the world. It found copper IUDs to be a safe and highly effective method of emergency contraception, with the additional advantage of simultaneously offering one of the most reliable and cost-effective contraceptive options.14

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION AT MID-CYCLE

Q: True or false? When choosing a method of emergency contraception, it is important to consider whether a woman is near ovulation during the time of intercourse.

A: True. Emergency contraception can prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse, but it does not always work. The most widely used method, levonorgestrel 1.5 mg orally within 72 hours of intercourse, prevents at least 50% of pregnancies that would have occurred in the absence of its use.15 Glasier et al16 showed that emergency contraception was more likely to fail if a woman had unprotected intercourse around the time of ovulation.16

Though it can be difficult for women to tell if they are in the fertile times of their cycle, it might be helpful to try to identify women who have intercourse at mid-cycle, when the risk of pregnancy is greatest. Because insertion of an IUD and use of ulipristal acetate probably prevent more pregnancies, these methods might be preferred over levonorgestrel-based regimens during these higher-risk situations.

OBESE PATIENTS

Q: True or false? Hormonal emergency contraception is more likely to fail in obese patients.

A: True. Most recent evidence shows that whichever oral emergency contraceptive drug is taken, the risk of pregnancy is more than 3 times greater for obese women (OR 3.60, 95% CI 1.96–6.53) and 1.5 times greater for overweight women (OR 1.53, 95% CI 0.75–2.95).16 Of all covariates tested, those that were shown to increase the odds of failure of the emergency contraception were higher body mass index, further unprotected intercourse, and conception probability (based on time of fertility cycle). In fact, among obese women treated with levonorgestrel, the observed pregnancy rate was 5.8%, which is slightly above the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of emergency contraception, suggesting that for obese women levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception may even be ineffective.

This is in line with recent reports suggesting that oral contraceptives are less effective in obese women. More effective regimens such as an IUD or ulipristal might be preferred in these women. However, obesity should not be used as a reason not to offer emergency contraception, as this is the last chance these women have to prevent pregnancy.

IS IT ABORTION?

Q: True or false? Emergency contraception does not cause abortion.

A: True, but patients may ask for more details about this. Hormonal emergency contraception works primarily by delaying or inhibiting ovulation and inhibiting fertilization.

Levonorgestrel or combined estrogen-progestin-based methods would be unlikely to have any adverse effects on the endometrium after fertilization, since they would only serve to enhance the progesterone effect. Therefore, they are unlikely to affect the ability of the embryo to attach to the endometrium.

Ulipristal, on the other hand, can have just the opposite effect on the postovulatory endometrium because of its inhibitory action on progesterone. Ulipristal is structurally similar to mifepristone, and its mechanism of action varies depending on the time of administration during the menstrual cycle. When unprotected intercourse occurs during a time when fertility is not possible, ulipristal behaves like a placebo. When intercourse occurs just before ovulation, ulipristal acts by delaying ovulation and thereby preventing fertilization (similar to levonorgestrel). Ulipristal may have an additional action of affecting the ability of the embryo to either attach to the endometrium or maintain its attachment, by a variety of mechanisms of action.17,18 Because of this, some in the popular press and on the Internet have spoken out against the use of ulipristal.

The ACOG considers pregnancy to begin not with fertilization of the egg but with implantation, as demonstrated by a positive pregnancy test.

Of note, the copper IUD also prevents implantation after fertilization, which likely explains its high efficacy.

Women who have detailed questions about this can be counseled that levonorgestrel works mostly by preventing ovulation, and that ulipristal and the copper IUD might also work via postfertilization mechanisms. However, they are not considered to be abortive, based on standard definitions of pregnancy.

If a woman is pregnant and she takes levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception, this has not been shown to have any adverse effects on the fetus (similar to oral contraceptives).

Ulipristal is classified as pregnancy category X, and therefore its use during pregnancy is contraindicated. Based on information provided by the manufacturer, there are no adequate, well-controlled studies of ulipristal use in pregnant women. Although fetal loss was observed in animal studies after ulipristal administration (during the period of organogenesis), no malformations or adverse events were present in the surviving fetuses. Ulipristal is not indicated for termination of an existing pregnancy.

DO THE USUAL CONTRAINDICATIONS TO HORMONAL CONTRACEPTIVES APPLY?

Q: True or false? Because emergency contraception has such a short duration of exposure, the usual medical contraindications to hormonal therapies do not apply to it.

A: True. The usual contraindications to the use of hormonal contraceptives (eg, migraine with aura, hypertension, history of venous thromboembolism) do not apply to emergency contraception because of the short time of exposure.19 Furthermore, the risks associated with pregnancy in these women would likely outweigh any risks associated with emergency contraception.

However, one must be cognizant of potential drug interactions. According to the manufacturer, the use of ulipristal did not inhibit or induce cytochrome P 450 enzymes in vitro; therefore, in vivo studies were not performed. But because ulipristal is metabolized primarily via CYP3A4, an interaction between agents that induce or inhibit CYP3A4 could occur.20 Thus, concomitant use of drugs such as barbiturates, rifampin (Rifadin), St. John’s wort, or antiseizure drugs such as topiramate (Topamax) may lower ulipristal concentrations. These medications may also affect levonorgestrel levels, similar to their effects on combined hormonal contraception. However, it is not known whether this translates to decreased efficacy.

When a woman is taking medications that can potentially decrease the effectiveness of hormonal emergency contraception, a more effective method such as a copper IUD might be more strongly considered. If a woman is not interested in an IUD, oral emergency contraception should still be offered, given that this is one of the last chances to prevent pregnancy, especially if she is on a potential teratogen.

Oral contraceptive pills have not been studied in combination with ulipristal. However, because ulipristal binds with high affinity to progesterone receptors (thus competing with the contraceptive), use of additional barrier contraceptives is recommended for the remainder of the menstrual cycle.

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION AND BREASTFEEDING

Q: True of false? Emergency contraceptives can be used if a woman is breastfeeding.

A: That depends on which method is used. Both the ACOG and the World Health Organization state that it is safe for breastfeeding women to use emergency contraception, but these are older guidelines addressing progestin-only regimens (ie, levonorgestrel).19,21 It is unknown whether ulipristal is secreted into human breast milk, although excretion was seen in animal studies. Therefore, ulipristal is not recommended for use by women who are breastfeeding.20,22 To minimize the infant’s exposure to levonorgestrel, mothers should consider not nursing for at least 8 hours after ingestion, but no more than 24 hours is needed.23

- Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2011; 43:41–50.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011; 84:478–485.

- Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Contraceptive use among US women having abortions in 2000–2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2002; 34:294–303.

- Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2010; 23. http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/series/sr_23/sr23_029.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- Harrison T. Availability of emergency contraception: a survey of hospital emergency department staff. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 46:105–110.

- Goldenring JM, Allred G. Post-rape care in hospital emergency rooms. Am J Public Health 2001; 91:1169–1170.

- Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet 1998; 352:428–433.

- Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer DF, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108:1089–1097.

- Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:555–562.

- Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Mifepristone (RU 486) compared with high-dose estrogen and progestogen for emergency postcoital contraception. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:1041–1044.

- Glasier A. Emergency postcoital contraception. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1058–1064.

- Stanford JB, Mikolajczyk RT. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices: update and estimation of postfertilization effects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187:1699–1708.

- Zhou L, Xiao B. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: a multicenter clinical trial. Contraception 2001; 64:107–112.

- Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod 2012; 27:1994–2000.

- Trussell J, Ellertson C, von Hertzen H, et al. Estimating the effectiveness of emergency contraceptive pills. Contraception 2003; 67:259–265.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception 2011; 84:363–367.

- Miech RP. Immunopharmacology of ulipristal as an emergency contraceptive. Int J Womens Health 2011; 3:391–397.

- Keenan JA. Ulipristal acetate: contraceptive or contragestive? Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:813–815.

- Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 3rd ed. Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization; 2004.

- Ella package insert. Morristown, NJ: Watson Pharmaceuticals; August 2010. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022474s000lbl.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2012.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 112: emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115:1100–1109.

- Orleans RJ. Clinical review. NDA22-474. Ella (ulipristal acetate 30 mg). US Food and Drug Administration, July 27, 2010. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/UCM295393.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- Gainer E, Massai R, Lillo S, et al. Levonorgestrel pharmacokinetics in plasma and milk of lactating women who take 1.5 mg for emergency contraception. Hum Reprod 2007; 22:1578–1584.

In the United States, nearly 50 million legal abortions were performed between 1973 and 2008.1 About half of pregnancies in American women are unintended, and 4 out of 10 unintended pregnancies are terminated by abortion.2 Of the women who had abortions, 54% had used a contraceptive method during the month they became pregnant.3

It is hoped that the expanded use of emergency contraception will translate into fewer abortions. However, in a 2006–2008 survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only 9.7% of women ages 15 to 44 reported ever having used emergency contraception.4 (To put this figure in perspective, a similar number—about 10%—of women in this age group become pregnant in any given year, half of them unintentionally.4) Clearly, patients need to be better educated in the methods of contraception and emergency contraception.

Hospitals are not meeting the need. Pretending to be in need of emergency contraception, Harrison5 called the emergency departments of all 597 Catholic hospitals in the United States and 615 (17%) of the non-Catholic hospitals. About half of the staff she spoke to said they do not dispense emergency contraception, even in cases of sexual assault. This was the case for both Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals. Of the people she talked to who said they did not provide emergency contraception under any circumstance, only about half gave her a phone number for another facility to try, and most of these phone numbers were wrong, were for facilities that were not open on weekends, or were for facilities that did not offer emergency contraception either. This is in spite of legal precedent, which indicates that failure to provide complete post-rape counseling, including emergency contraception, constitutes inadequate care and gives a woman the standing to sue the hospital.6

Clearly, better provider education is also needed in the area of emergency contraception. The Association of Reproductive Health Professionals has a helpful Web site for providers and for patients. In addition to up-to-date information about contraceptive and emergency contraceptive choices, it provides advice on how to discuss emergency contraception with patients (www.arhp.org). We can test our own knowledge of this topic by reviewing the following questions.

WHICH PRODUCT IS MOST EFFECTIVE?

Q: True or false? Levonorgestrel monotherapy (Plan B One-Step, Next Choice) is the most effective oral emergency contraceptive.

A: False, although this statement was true before the US approval of ulipristal acetate (ella) in August 2010.

For many years levonorgestrel monotherapy has been the mainstay of emergency contraception, having replaced the combination estrogen-progestin (Yuzpe) regimen because of better tolerability and improved efficacy.7 Its main mechanism of action involves delaying ovulation. Levonorgestrel is given in two doses of 0.75 mg 12 hours apart, or as a single 1.5-mg dose (Table 1). Both formulations of levonorgestrel are available over the counter to women age 17 and older, or by prescription if they are under age 17.

However, a randomized controlled trial showed that women treated with ulipristal had about half the number of pregnancies than in those treated with levonorgestrel, with pregnancy rates of 0.9% vs 1.7%.8

HOW WIDE IS THE WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY?

Q: True or false? Both ulipristal and levonorgestrel can be taken up to 120 hours (5 days) after unprotected intercourse. However, ulipristal maintains its effectiveness throughout this time, whereas levonorgestrel becomes less effective the longer a patient waits to take it.

A: True. Ulipristal is a second-generation selective progesterone receptor modulator. These drugs can function as agonists, antagonists, or mixed agonist-antagonists at the progesterone receptor, depending on the tissue affected. Ulipristal is given as a one-time, 30-mg dose within 120 hours of intercourse.

In a study of 1,696 women, 844 of whom received ulipristal acetate and 852 of whom received levonorgestrel, ulipristal was at least as effective as levonorgestrel when used within 72 hours of intercourse for emergency contraception, with 15 pregnancies in the ulipristal group and 22 pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group (odds ratio [OR] 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35–1.31]). However, ulipristal prevented significantly more pregnancies than levonorgestrel at 72 to 120 hours, with no pregnancies in the ulipristal group and three pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group.9

Because ulipristal has a long half-life (32 hours), it can delay ovulation beyond the life span of sperm, thereby extending the window of opportunity for emergency contraception. However, patients should be advised to avoid further unprotected intercourse after the use of emergency contraception. Because emergency contraception works mainly by delaying ovulation, it may increase the likelihood of pregnancy if the patient has unprotected intercourse again several days later.

IS MIFEPRISTONE AN EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTIVE?

Q: True or false? In the United States, mifepristone (Mifeprex), also known as RU-486, is available for use as an emergency contraceptive in addition to its use in abortion.

A: False, even though mifepristone, another selective progesterone receptor modulator, is highly effective when used up to 120 hours after intercourse. In fact, it might be effective up to 17 days after unprotected intercourse.10

Although mifepristone is one of the most effective forms of emergency contraception, social and political controversy has prevented its approval in the United States. However, it is approved for use as an abortifacient, at a higher dose than would be used for emergency contraception.

Unlike levonorgestrel, mifepristone exerts its effect via two potential mechanisms: delaying ovulation and preventing implantation.11

IUDs AS EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

Q: True or false? Insertion of a 5-year intrauterine device (IUD), ie, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena), is 99.8% effective at preventing pregnancy when used within 5 days of unprotected intercourse.

A: False. The Mirena IUD has not been studied as a form of emergency contraception. However, this statement would be true for the 10-year copper IUD ParaGard. Copper-releasing IUDs are considered a very effective method of emergency contraception, with associated pregnancy rates of 0.0% to 0.2% when inserted up until implantation (within 5 days after ovulation).12,13 If desired, the IUD can then be kept in place for up to 10 years as a method of birth control.

However, this method requires the ready availability of a health professional trained to do the insertion. It is also important to make sure that the patient will not be at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections from further unprotected intercourse. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that an IUD be placed within 5 days of unprotected intercourse for use as emergency contraception.

A recent review looked at 42 published studies of copper IUDs used for emergency contraception around the world. It found copper IUDs to be a safe and highly effective method of emergency contraception, with the additional advantage of simultaneously offering one of the most reliable and cost-effective contraceptive options.14

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION AT MID-CYCLE

Q: True or false? When choosing a method of emergency contraception, it is important to consider whether a woman is near ovulation during the time of intercourse.

A: True. Emergency contraception can prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse, but it does not always work. The most widely used method, levonorgestrel 1.5 mg orally within 72 hours of intercourse, prevents at least 50% of pregnancies that would have occurred in the absence of its use.15 Glasier et al16 showed that emergency contraception was more likely to fail if a woman had unprotected intercourse around the time of ovulation.16

Though it can be difficult for women to tell if they are in the fertile times of their cycle, it might be helpful to try to identify women who have intercourse at mid-cycle, when the risk of pregnancy is greatest. Because insertion of an IUD and use of ulipristal acetate probably prevent more pregnancies, these methods might be preferred over levonorgestrel-based regimens during these higher-risk situations.

OBESE PATIENTS

Q: True or false? Hormonal emergency contraception is more likely to fail in obese patients.

A: True. Most recent evidence shows that whichever oral emergency contraceptive drug is taken, the risk of pregnancy is more than 3 times greater for obese women (OR 3.60, 95% CI 1.96–6.53) and 1.5 times greater for overweight women (OR 1.53, 95% CI 0.75–2.95).16 Of all covariates tested, those that were shown to increase the odds of failure of the emergency contraception were higher body mass index, further unprotected intercourse, and conception probability (based on time of fertility cycle). In fact, among obese women treated with levonorgestrel, the observed pregnancy rate was 5.8%, which is slightly above the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of emergency contraception, suggesting that for obese women levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception may even be ineffective.

This is in line with recent reports suggesting that oral contraceptives are less effective in obese women. More effective regimens such as an IUD or ulipristal might be preferred in these women. However, obesity should not be used as a reason not to offer emergency contraception, as this is the last chance these women have to prevent pregnancy.

IS IT ABORTION?

Q: True or false? Emergency contraception does not cause abortion.

A: True, but patients may ask for more details about this. Hormonal emergency contraception works primarily by delaying or inhibiting ovulation and inhibiting fertilization.

Levonorgestrel or combined estrogen-progestin-based methods would be unlikely to have any adverse effects on the endometrium after fertilization, since they would only serve to enhance the progesterone effect. Therefore, they are unlikely to affect the ability of the embryo to attach to the endometrium.

Ulipristal, on the other hand, can have just the opposite effect on the postovulatory endometrium because of its inhibitory action on progesterone. Ulipristal is structurally similar to mifepristone, and its mechanism of action varies depending on the time of administration during the menstrual cycle. When unprotected intercourse occurs during a time when fertility is not possible, ulipristal behaves like a placebo. When intercourse occurs just before ovulation, ulipristal acts by delaying ovulation and thereby preventing fertilization (similar to levonorgestrel). Ulipristal may have an additional action of affecting the ability of the embryo to either attach to the endometrium or maintain its attachment, by a variety of mechanisms of action.17,18 Because of this, some in the popular press and on the Internet have spoken out against the use of ulipristal.

The ACOG considers pregnancy to begin not with fertilization of the egg but with implantation, as demonstrated by a positive pregnancy test.

Of note, the copper IUD also prevents implantation after fertilization, which likely explains its high efficacy.

Women who have detailed questions about this can be counseled that levonorgestrel works mostly by preventing ovulation, and that ulipristal and the copper IUD might also work via postfertilization mechanisms. However, they are not considered to be abortive, based on standard definitions of pregnancy.

If a woman is pregnant and she takes levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception, this has not been shown to have any adverse effects on the fetus (similar to oral contraceptives).

Ulipristal is classified as pregnancy category X, and therefore its use during pregnancy is contraindicated. Based on information provided by the manufacturer, there are no adequate, well-controlled studies of ulipristal use in pregnant women. Although fetal loss was observed in animal studies after ulipristal administration (during the period of organogenesis), no malformations or adverse events were present in the surviving fetuses. Ulipristal is not indicated for termination of an existing pregnancy.

DO THE USUAL CONTRAINDICATIONS TO HORMONAL CONTRACEPTIVES APPLY?

Q: True or false? Because emergency contraception has such a short duration of exposure, the usual medical contraindications to hormonal therapies do not apply to it.

A: True. The usual contraindications to the use of hormonal contraceptives (eg, migraine with aura, hypertension, history of venous thromboembolism) do not apply to emergency contraception because of the short time of exposure.19 Furthermore, the risks associated with pregnancy in these women would likely outweigh any risks associated with emergency contraception.

However, one must be cognizant of potential drug interactions. According to the manufacturer, the use of ulipristal did not inhibit or induce cytochrome P 450 enzymes in vitro; therefore, in vivo studies were not performed. But because ulipristal is metabolized primarily via CYP3A4, an interaction between agents that induce or inhibit CYP3A4 could occur.20 Thus, concomitant use of drugs such as barbiturates, rifampin (Rifadin), St. John’s wort, or antiseizure drugs such as topiramate (Topamax) may lower ulipristal concentrations. These medications may also affect levonorgestrel levels, similar to their effects on combined hormonal contraception. However, it is not known whether this translates to decreased efficacy.

When a woman is taking medications that can potentially decrease the effectiveness of hormonal emergency contraception, a more effective method such as a copper IUD might be more strongly considered. If a woman is not interested in an IUD, oral emergency contraception should still be offered, given that this is one of the last chances to prevent pregnancy, especially if she is on a potential teratogen.

Oral contraceptive pills have not been studied in combination with ulipristal. However, because ulipristal binds with high affinity to progesterone receptors (thus competing with the contraceptive), use of additional barrier contraceptives is recommended for the remainder of the menstrual cycle.

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION AND BREASTFEEDING

Q: True of false? Emergency contraceptives can be used if a woman is breastfeeding.

A: That depends on which method is used. Both the ACOG and the World Health Organization state that it is safe for breastfeeding women to use emergency contraception, but these are older guidelines addressing progestin-only regimens (ie, levonorgestrel).19,21 It is unknown whether ulipristal is secreted into human breast milk, although excretion was seen in animal studies. Therefore, ulipristal is not recommended for use by women who are breastfeeding.20,22 To minimize the infant’s exposure to levonorgestrel, mothers should consider not nursing for at least 8 hours after ingestion, but no more than 24 hours is needed.23

In the United States, nearly 50 million legal abortions were performed between 1973 and 2008.1 About half of pregnancies in American women are unintended, and 4 out of 10 unintended pregnancies are terminated by abortion.2 Of the women who had abortions, 54% had used a contraceptive method during the month they became pregnant.3

It is hoped that the expanded use of emergency contraception will translate into fewer abortions. However, in a 2006–2008 survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only 9.7% of women ages 15 to 44 reported ever having used emergency contraception.4 (To put this figure in perspective, a similar number—about 10%—of women in this age group become pregnant in any given year, half of them unintentionally.4) Clearly, patients need to be better educated in the methods of contraception and emergency contraception.

Hospitals are not meeting the need. Pretending to be in need of emergency contraception, Harrison5 called the emergency departments of all 597 Catholic hospitals in the United States and 615 (17%) of the non-Catholic hospitals. About half of the staff she spoke to said they do not dispense emergency contraception, even in cases of sexual assault. This was the case for both Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals. Of the people she talked to who said they did not provide emergency contraception under any circumstance, only about half gave her a phone number for another facility to try, and most of these phone numbers were wrong, were for facilities that were not open on weekends, or were for facilities that did not offer emergency contraception either. This is in spite of legal precedent, which indicates that failure to provide complete post-rape counseling, including emergency contraception, constitutes inadequate care and gives a woman the standing to sue the hospital.6

Clearly, better provider education is also needed in the area of emergency contraception. The Association of Reproductive Health Professionals has a helpful Web site for providers and for patients. In addition to up-to-date information about contraceptive and emergency contraceptive choices, it provides advice on how to discuss emergency contraception with patients (www.arhp.org). We can test our own knowledge of this topic by reviewing the following questions.

WHICH PRODUCT IS MOST EFFECTIVE?

Q: True or false? Levonorgestrel monotherapy (Plan B One-Step, Next Choice) is the most effective oral emergency contraceptive.

A: False, although this statement was true before the US approval of ulipristal acetate (ella) in August 2010.

For many years levonorgestrel monotherapy has been the mainstay of emergency contraception, having replaced the combination estrogen-progestin (Yuzpe) regimen because of better tolerability and improved efficacy.7 Its main mechanism of action involves delaying ovulation. Levonorgestrel is given in two doses of 0.75 mg 12 hours apart, or as a single 1.5-mg dose (Table 1). Both formulations of levonorgestrel are available over the counter to women age 17 and older, or by prescription if they are under age 17.

However, a randomized controlled trial showed that women treated with ulipristal had about half the number of pregnancies than in those treated with levonorgestrel, with pregnancy rates of 0.9% vs 1.7%.8

HOW WIDE IS THE WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY?

Q: True or false? Both ulipristal and levonorgestrel can be taken up to 120 hours (5 days) after unprotected intercourse. However, ulipristal maintains its effectiveness throughout this time, whereas levonorgestrel becomes less effective the longer a patient waits to take it.

A: True. Ulipristal is a second-generation selective progesterone receptor modulator. These drugs can function as agonists, antagonists, or mixed agonist-antagonists at the progesterone receptor, depending on the tissue affected. Ulipristal is given as a one-time, 30-mg dose within 120 hours of intercourse.

In a study of 1,696 women, 844 of whom received ulipristal acetate and 852 of whom received levonorgestrel, ulipristal was at least as effective as levonorgestrel when used within 72 hours of intercourse for emergency contraception, with 15 pregnancies in the ulipristal group and 22 pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group (odds ratio [OR] 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35–1.31]). However, ulipristal prevented significantly more pregnancies than levonorgestrel at 72 to 120 hours, with no pregnancies in the ulipristal group and three pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group.9

Because ulipristal has a long half-life (32 hours), it can delay ovulation beyond the life span of sperm, thereby extending the window of opportunity for emergency contraception. However, patients should be advised to avoid further unprotected intercourse after the use of emergency contraception. Because emergency contraception works mainly by delaying ovulation, it may increase the likelihood of pregnancy if the patient has unprotected intercourse again several days later.

IS MIFEPRISTONE AN EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTIVE?

Q: True or false? In the United States, mifepristone (Mifeprex), also known as RU-486, is available for use as an emergency contraceptive in addition to its use in abortion.

A: False, even though mifepristone, another selective progesterone receptor modulator, is highly effective when used up to 120 hours after intercourse. In fact, it might be effective up to 17 days after unprotected intercourse.10

Although mifepristone is one of the most effective forms of emergency contraception, social and political controversy has prevented its approval in the United States. However, it is approved for use as an abortifacient, at a higher dose than would be used for emergency contraception.

Unlike levonorgestrel, mifepristone exerts its effect via two potential mechanisms: delaying ovulation and preventing implantation.11

IUDs AS EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

Q: True or false? Insertion of a 5-year intrauterine device (IUD), ie, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena), is 99.8% effective at preventing pregnancy when used within 5 days of unprotected intercourse.

A: False. The Mirena IUD has not been studied as a form of emergency contraception. However, this statement would be true for the 10-year copper IUD ParaGard. Copper-releasing IUDs are considered a very effective method of emergency contraception, with associated pregnancy rates of 0.0% to 0.2% when inserted up until implantation (within 5 days after ovulation).12,13 If desired, the IUD can then be kept in place for up to 10 years as a method of birth control.

However, this method requires the ready availability of a health professional trained to do the insertion. It is also important to make sure that the patient will not be at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections from further unprotected intercourse. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that an IUD be placed within 5 days of unprotected intercourse for use as emergency contraception.

A recent review looked at 42 published studies of copper IUDs used for emergency contraception around the world. It found copper IUDs to be a safe and highly effective method of emergency contraception, with the additional advantage of simultaneously offering one of the most reliable and cost-effective contraceptive options.14

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION AT MID-CYCLE

Q: True or false? When choosing a method of emergency contraception, it is important to consider whether a woman is near ovulation during the time of intercourse.

A: True. Emergency contraception can prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse, but it does not always work. The most widely used method, levonorgestrel 1.5 mg orally within 72 hours of intercourse, prevents at least 50% of pregnancies that would have occurred in the absence of its use.15 Glasier et al16 showed that emergency contraception was more likely to fail if a woman had unprotected intercourse around the time of ovulation.16

Though it can be difficult for women to tell if they are in the fertile times of their cycle, it might be helpful to try to identify women who have intercourse at mid-cycle, when the risk of pregnancy is greatest. Because insertion of an IUD and use of ulipristal acetate probably prevent more pregnancies, these methods might be preferred over levonorgestrel-based regimens during these higher-risk situations.

OBESE PATIENTS

Q: True or false? Hormonal emergency contraception is more likely to fail in obese patients.

A: True. Most recent evidence shows that whichever oral emergency contraceptive drug is taken, the risk of pregnancy is more than 3 times greater for obese women (OR 3.60, 95% CI 1.96–6.53) and 1.5 times greater for overweight women (OR 1.53, 95% CI 0.75–2.95).16 Of all covariates tested, those that were shown to increase the odds of failure of the emergency contraception were higher body mass index, further unprotected intercourse, and conception probability (based on time of fertility cycle). In fact, among obese women treated with levonorgestrel, the observed pregnancy rate was 5.8%, which is slightly above the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of emergency contraception, suggesting that for obese women levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception may even be ineffective.

This is in line with recent reports suggesting that oral contraceptives are less effective in obese women. More effective regimens such as an IUD or ulipristal might be preferred in these women. However, obesity should not be used as a reason not to offer emergency contraception, as this is the last chance these women have to prevent pregnancy.

IS IT ABORTION?

Q: True or false? Emergency contraception does not cause abortion.

A: True, but patients may ask for more details about this. Hormonal emergency contraception works primarily by delaying or inhibiting ovulation and inhibiting fertilization.

Levonorgestrel or combined estrogen-progestin-based methods would be unlikely to have any adverse effects on the endometrium after fertilization, since they would only serve to enhance the progesterone effect. Therefore, they are unlikely to affect the ability of the embryo to attach to the endometrium.

Ulipristal, on the other hand, can have just the opposite effect on the postovulatory endometrium because of its inhibitory action on progesterone. Ulipristal is structurally similar to mifepristone, and its mechanism of action varies depending on the time of administration during the menstrual cycle. When unprotected intercourse occurs during a time when fertility is not possible, ulipristal behaves like a placebo. When intercourse occurs just before ovulation, ulipristal acts by delaying ovulation and thereby preventing fertilization (similar to levonorgestrel). Ulipristal may have an additional action of affecting the ability of the embryo to either attach to the endometrium or maintain its attachment, by a variety of mechanisms of action.17,18 Because of this, some in the popular press and on the Internet have spoken out against the use of ulipristal.

The ACOG considers pregnancy to begin not with fertilization of the egg but with implantation, as demonstrated by a positive pregnancy test.

Of note, the copper IUD also prevents implantation after fertilization, which likely explains its high efficacy.

Women who have detailed questions about this can be counseled that levonorgestrel works mostly by preventing ovulation, and that ulipristal and the copper IUD might also work via postfertilization mechanisms. However, they are not considered to be abortive, based on standard definitions of pregnancy.

If a woman is pregnant and she takes levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception, this has not been shown to have any adverse effects on the fetus (similar to oral contraceptives).

Ulipristal is classified as pregnancy category X, and therefore its use during pregnancy is contraindicated. Based on information provided by the manufacturer, there are no adequate, well-controlled studies of ulipristal use in pregnant women. Although fetal loss was observed in animal studies after ulipristal administration (during the period of organogenesis), no malformations or adverse events were present in the surviving fetuses. Ulipristal is not indicated for termination of an existing pregnancy.

DO THE USUAL CONTRAINDICATIONS TO HORMONAL CONTRACEPTIVES APPLY?

Q: True or false? Because emergency contraception has such a short duration of exposure, the usual medical contraindications to hormonal therapies do not apply to it.

A: True. The usual contraindications to the use of hormonal contraceptives (eg, migraine with aura, hypertension, history of venous thromboembolism) do not apply to emergency contraception because of the short time of exposure.19 Furthermore, the risks associated with pregnancy in these women would likely outweigh any risks associated with emergency contraception.

However, one must be cognizant of potential drug interactions. According to the manufacturer, the use of ulipristal did not inhibit or induce cytochrome P 450 enzymes in vitro; therefore, in vivo studies were not performed. But because ulipristal is metabolized primarily via CYP3A4, an interaction between agents that induce or inhibit CYP3A4 could occur.20 Thus, concomitant use of drugs such as barbiturates, rifampin (Rifadin), St. John’s wort, or antiseizure drugs such as topiramate (Topamax) may lower ulipristal concentrations. These medications may also affect levonorgestrel levels, similar to their effects on combined hormonal contraception. However, it is not known whether this translates to decreased efficacy.

When a woman is taking medications that can potentially decrease the effectiveness of hormonal emergency contraception, a more effective method such as a copper IUD might be more strongly considered. If a woman is not interested in an IUD, oral emergency contraception should still be offered, given that this is one of the last chances to prevent pregnancy, especially if she is on a potential teratogen.

Oral contraceptive pills have not been studied in combination with ulipristal. However, because ulipristal binds with high affinity to progesterone receptors (thus competing with the contraceptive), use of additional barrier contraceptives is recommended for the remainder of the menstrual cycle.

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION AND BREASTFEEDING

Q: True of false? Emergency contraceptives can be used if a woman is breastfeeding.

A: That depends on which method is used. Both the ACOG and the World Health Organization state that it is safe for breastfeeding women to use emergency contraception, but these are older guidelines addressing progestin-only regimens (ie, levonorgestrel).19,21 It is unknown whether ulipristal is secreted into human breast milk, although excretion was seen in animal studies. Therefore, ulipristal is not recommended for use by women who are breastfeeding.20,22 To minimize the infant’s exposure to levonorgestrel, mothers should consider not nursing for at least 8 hours after ingestion, but no more than 24 hours is needed.23

- Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2011; 43:41–50.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011; 84:478–485.

- Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Contraceptive use among US women having abortions in 2000–2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2002; 34:294–303.

- Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2010; 23. http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/series/sr_23/sr23_029.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- Harrison T. Availability of emergency contraception: a survey of hospital emergency department staff. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 46:105–110.

- Goldenring JM, Allred G. Post-rape care in hospital emergency rooms. Am J Public Health 2001; 91:1169–1170.

- Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet 1998; 352:428–433.

- Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer DF, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108:1089–1097.

- Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:555–562.

- Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Mifepristone (RU 486) compared with high-dose estrogen and progestogen for emergency postcoital contraception. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:1041–1044.

- Glasier A. Emergency postcoital contraception. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1058–1064.

- Stanford JB, Mikolajczyk RT. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices: update and estimation of postfertilization effects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187:1699–1708.

- Zhou L, Xiao B. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: a multicenter clinical trial. Contraception 2001; 64:107–112.

- Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod 2012; 27:1994–2000.

- Trussell J, Ellertson C, von Hertzen H, et al. Estimating the effectiveness of emergency contraceptive pills. Contraception 2003; 67:259–265.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception 2011; 84:363–367.

- Miech RP. Immunopharmacology of ulipristal as an emergency contraceptive. Int J Womens Health 2011; 3:391–397.

- Keenan JA. Ulipristal acetate: contraceptive or contragestive? Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:813–815.

- Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 3rd ed. Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization; 2004.

- Ella package insert. Morristown, NJ: Watson Pharmaceuticals; August 2010. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022474s000lbl.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2012.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 112: emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115:1100–1109.

- Orleans RJ. Clinical review. NDA22-474. Ella (ulipristal acetate 30 mg). US Food and Drug Administration, July 27, 2010. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/UCM295393.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- Gainer E, Massai R, Lillo S, et al. Levonorgestrel pharmacokinetics in plasma and milk of lactating women who take 1.5 mg for emergency contraception. Hum Reprod 2007; 22:1578–1584.

- Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2011; 43:41–50.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011; 84:478–485.

- Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Contraceptive use among US women having abortions in 2000–2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2002; 34:294–303.

- Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2010; 23. http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/series/sr_23/sr23_029.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- Harrison T. Availability of emergency contraception: a survey of hospital emergency department staff. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 46:105–110.

- Goldenring JM, Allred G. Post-rape care in hospital emergency rooms. Am J Public Health 2001; 91:1169–1170.

- Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet 1998; 352:428–433.

- Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer DF, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108:1089–1097.

- Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:555–562.

- Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Mifepristone (RU 486) compared with high-dose estrogen and progestogen for emergency postcoital contraception. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:1041–1044.

- Glasier A. Emergency postcoital contraception. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1058–1064.

- Stanford JB, Mikolajczyk RT. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices: update and estimation of postfertilization effects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187:1699–1708.

- Zhou L, Xiao B. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: a multicenter clinical trial. Contraception 2001; 64:107–112.

- Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod 2012; 27:1994–2000.

- Trussell J, Ellertson C, von Hertzen H, et al. Estimating the effectiveness of emergency contraceptive pills. Contraception 2003; 67:259–265.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception 2011; 84:363–367.

- Miech RP. Immunopharmacology of ulipristal as an emergency contraceptive. Int J Womens Health 2011; 3:391–397.

- Keenan JA. Ulipristal acetate: contraceptive or contragestive? Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:813–815.

- Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 3rd ed. Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization; 2004.

- Ella package insert. Morristown, NJ: Watson Pharmaceuticals; August 2010. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022474s000lbl.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2012.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 112: emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115:1100–1109.

- Orleans RJ. Clinical review. NDA22-474. Ella (ulipristal acetate 30 mg). US Food and Drug Administration, July 27, 2010. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/UCM295393.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- Gainer E, Massai R, Lillo S, et al. Levonorgestrel pharmacokinetics in plasma and milk of lactating women who take 1.5 mg for emergency contraception. Hum Reprod 2007; 22:1578–1584.

KEY POINTS

- Levonorgestrel-based emergency contraceptives such as Plan B One-Step, Next Choice, and generics are now available over the counter, which has the advantage of avoiding the delays and hassles of calling the doctor’s office and waiting for prescriptions. But patients still need our guidance on how and when to use emergency contraception.

- Even if patients now have easy access to over-the-counter emergency contraceptives, we physicians should take every opportunity to discuss effective contraceptive options with our patients.

- Ulipristal and copper intrauterine devices (ParaGard) are likely to be more effective than levonorgestrel and should be considered in women at highest risk of pregnancy, such as those who are obese.

- Prescribers should feel comfortable addressing tough questions about mechanisms of action, as controversies and myths about emergency contraception are regularly discussed in the media and on the Internet.