User login

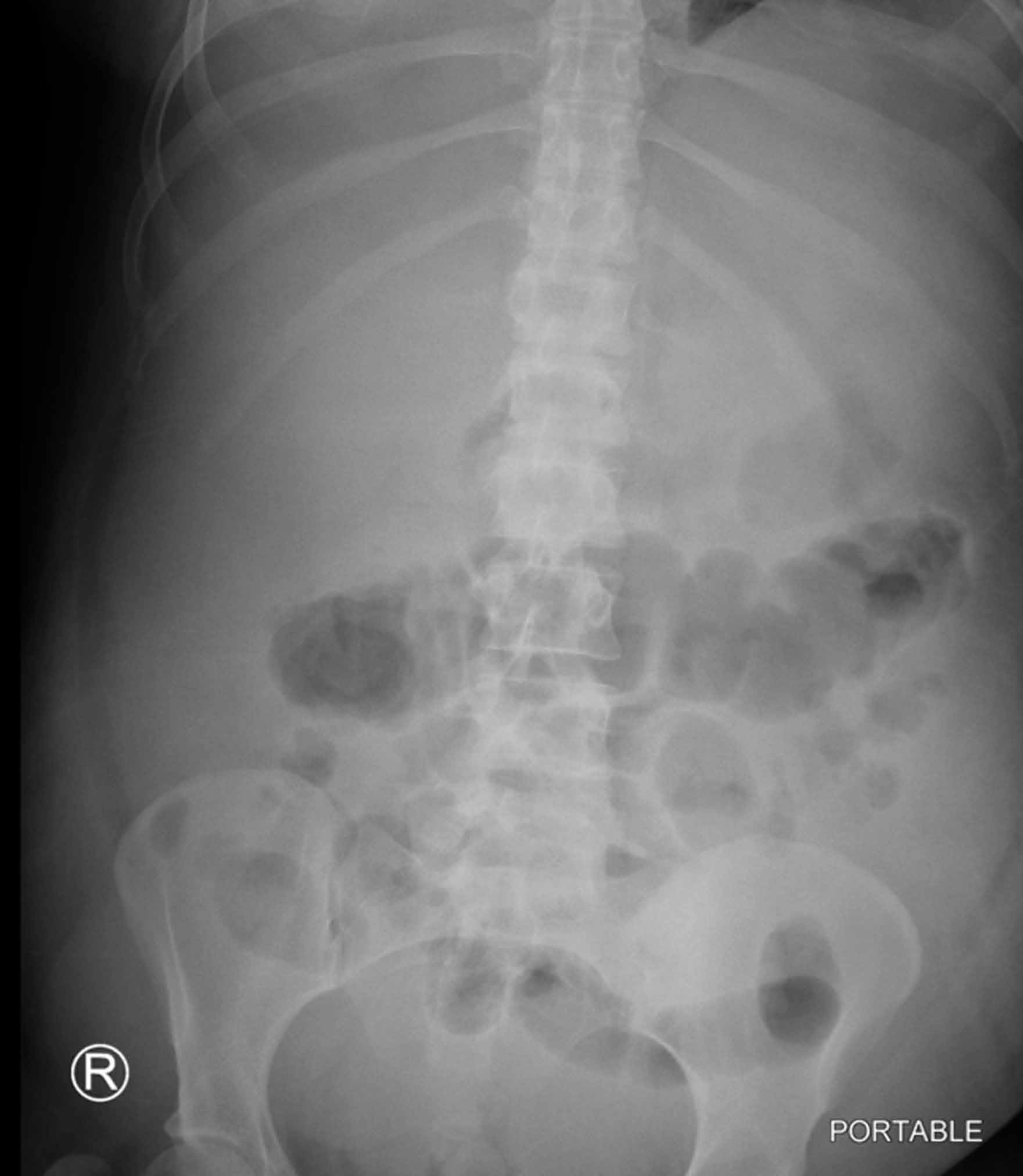

30-year-old woman with a history of alcoholism and anxiety presented to the ED for evaluation of abdominal distension and pain. She reported new social stressors at home and increased alcohol consumption. She also noted gradually increasing abdominal distension over the past several weeks. As patient’s liver function tests were elevated, supine radiographs of the abdomen were acquired for further evaluation; a representative image is presented below (Figure 1a).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Is any additional imaging required?

Answer

Centralization of bowel is suggestive of abdominopelvic ascites.1 Additional radiographic findings that may be seen with ascites include diffusely increased density of the abdomen and bulging of the peritoneal fat stripes/flanks. In the average adult, a minimum of approximately 800 mL of ascitic fluid is required to medially displace bowel loops or abdominal viscera.2 While there are many causes of ascites, the radiograph in this case suggests the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Although the top of the liver is not visualized on the radiograph, the liver contour appears enlarged (red arrow, Figure 1b).

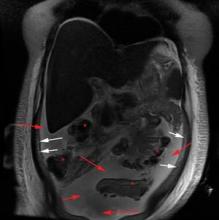

In the ED, ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice to confirm the presence of ascites as it is widely available, quick, relatively inexpensive, and does not require ionizing radiation. Ultrasound is also useful when examining the abdominal viscera since it may detect the underlying cause of ascites.3 The ultrasound image of the abdominal viscera in this case demonstrated a hypoechoic (dark) signal (red arrow, Figure 1c) between the abdominal wall (red asterisk, Figure 1c) and bowel loops (letter ‘B,” Figure 1c). This finding confirmed the presence of ascites because simple fluid does not reflect the ultrasound beam, but instead results in the hypoechoic signal seen in Figure 1c. An additional sonographic image confirmed the presence of an enlarged liver (white asterisk, Figure 1d) and ascites in the right upper quadrant (red arrow, Figure 1d).

The patient was admitted for further workup and treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis. A

Dr Lyons is a resident in the department of radiology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-

- Meschan I. Analysis of Roentgen Signs in General Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1973:1231.

- Keeffee EJ, Gagliardi RA, Pfister RC. The roentgenographic evaluation of ascites. Am J Roentgenol. 1967;101(2):388-396.

- Goldberg BB, Goodman GA, Clearfield HR. Evaluation of ascites by ultrasound. Radiology. 1970;96(1):15-22.

30-year-old woman with a history of alcoholism and anxiety presented to the ED for evaluation of abdominal distension and pain. She reported new social stressors at home and increased alcohol consumption. She also noted gradually increasing abdominal distension over the past several weeks. As patient’s liver function tests were elevated, supine radiographs of the abdomen were acquired for further evaluation; a representative image is presented below (Figure 1a).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Is any additional imaging required?

Answer

Centralization of bowel is suggestive of abdominopelvic ascites.1 Additional radiographic findings that may be seen with ascites include diffusely increased density of the abdomen and bulging of the peritoneal fat stripes/flanks. In the average adult, a minimum of approximately 800 mL of ascitic fluid is required to medially displace bowel loops or abdominal viscera.2 While there are many causes of ascites, the radiograph in this case suggests the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Although the top of the liver is not visualized on the radiograph, the liver contour appears enlarged (red arrow, Figure 1b).

In the ED, ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice to confirm the presence of ascites as it is widely available, quick, relatively inexpensive, and does not require ionizing radiation. Ultrasound is also useful when examining the abdominal viscera since it may detect the underlying cause of ascites.3 The ultrasound image of the abdominal viscera in this case demonstrated a hypoechoic (dark) signal (red arrow, Figure 1c) between the abdominal wall (red asterisk, Figure 1c) and bowel loops (letter ‘B,” Figure 1c). This finding confirmed the presence of ascites because simple fluid does not reflect the ultrasound beam, but instead results in the hypoechoic signal seen in Figure 1c. An additional sonographic image confirmed the presence of an enlarged liver (white asterisk, Figure 1d) and ascites in the right upper quadrant (red arrow, Figure 1d).

The patient was admitted for further workup and treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis. A

Dr Lyons is a resident in the department of radiology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-

30-year-old woman with a history of alcoholism and anxiety presented to the ED for evaluation of abdominal distension and pain. She reported new social stressors at home and increased alcohol consumption. She also noted gradually increasing abdominal distension over the past several weeks. As patient’s liver function tests were elevated, supine radiographs of the abdomen were acquired for further evaluation; a representative image is presented below (Figure 1a).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Is any additional imaging required?

Answer

Centralization of bowel is suggestive of abdominopelvic ascites.1 Additional radiographic findings that may be seen with ascites include diffusely increased density of the abdomen and bulging of the peritoneal fat stripes/flanks. In the average adult, a minimum of approximately 800 mL of ascitic fluid is required to medially displace bowel loops or abdominal viscera.2 While there are many causes of ascites, the radiograph in this case suggests the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Although the top of the liver is not visualized on the radiograph, the liver contour appears enlarged (red arrow, Figure 1b).

In the ED, ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice to confirm the presence of ascites as it is widely available, quick, relatively inexpensive, and does not require ionizing radiation. Ultrasound is also useful when examining the abdominal viscera since it may detect the underlying cause of ascites.3 The ultrasound image of the abdominal viscera in this case demonstrated a hypoechoic (dark) signal (red arrow, Figure 1c) between the abdominal wall (red asterisk, Figure 1c) and bowel loops (letter ‘B,” Figure 1c). This finding confirmed the presence of ascites because simple fluid does not reflect the ultrasound beam, but instead results in the hypoechoic signal seen in Figure 1c. An additional sonographic image confirmed the presence of an enlarged liver (white asterisk, Figure 1d) and ascites in the right upper quadrant (red arrow, Figure 1d).

The patient was admitted for further workup and treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis. A

Dr Lyons is a resident in the department of radiology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Wladyka is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and an assistant attending radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-

- Meschan I. Analysis of Roentgen Signs in General Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1973:1231.

- Keeffee EJ, Gagliardi RA, Pfister RC. The roentgenographic evaluation of ascites. Am J Roentgenol. 1967;101(2):388-396.

- Goldberg BB, Goodman GA, Clearfield HR. Evaluation of ascites by ultrasound. Radiology. 1970;96(1):15-22.

- Meschan I. Analysis of Roentgen Signs in General Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1973:1231.

- Keeffee EJ, Gagliardi RA, Pfister RC. The roentgenographic evaluation of ascites. Am J Roentgenol. 1967;101(2):388-396.

- Goldberg BB, Goodman GA, Clearfield HR. Evaluation of ascites by ultrasound. Radiology. 1970;96(1):15-22.