User login

When evaluating patients presenting with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, there are several imaging modalities to consider—ultrasound, computed tomography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan. In addition to the many benefits to choosing bedside ultrasound as an initial modality, it also carries the least amount of imaging-associated risks (eg, lowest amount of radiation, no exposure to ionizing radiation or radionucleotides). Moreover, not only can bedside ultrasound decrease the time to diagnosis, but it also reduces the length of patient stay by an average of 1 hour.1

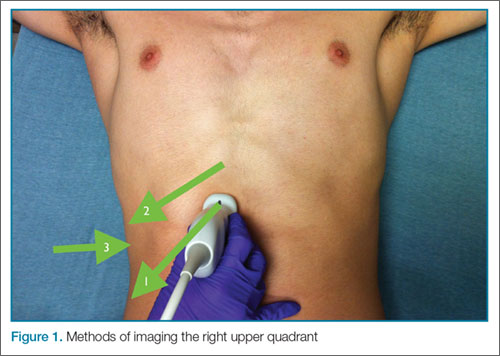

The patient is typically placed in the recumbent position, but in certain cases, placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position may improve visualization. The scan should begin by placing the low-frequency probe in a sagittal orientation with the indicator marker pointed toward the head. Starting in the midline subxiphoid position, the clinician should angle the probe underneath the costal margin and then slide it to the patient’s right side. This will typically bring the gallbladder into view. If the gallbladder is not identified in this first pass, a second sweep across the ribs can be performed. If the gallbladder is still not in view, the clinician should then try placing the probe on the patient’s right side near the midaxillary line and fanning though the liver in a coronal plane (Figure 1).

Once the gallbladder is located, it is important to ensure that both the long and short axis planes are completely visualized. This can be accomplished by rotating the probe. There are several techniques to confirm that the structure in view is the gallbladder. One approach is to use the color-flow option, which can help differentiate vascular structures from the gallbladder. The gallbladder, which is connected to the portal vein by the main lobar fissure, will appear as an exclamation point on the ultrasound image (Figure 2).

In ultrasound, pericholecystic fluid will appear around the gallbladder as small black triangular shapes. Gallstones have a hyperechoic anterior rim with posterior dark shadowing. Typically, gallstones are freely mobile unless they are stuck in the neck of the gallbladder, in which case, there is heightened concern for cholecystitis (Figure 2).

Visualization of the common bile duct can be challenging. Fortunately, most cases of acute cholecystitis can be diagnosed even without visualization of the common bile duct. When attempting visualization, however, the common bile duct can be found by tracing the main lobar fissure to the portal vein. The portal triad (commonly referred to as the “Mickey Mouse” sign) comprises the portal vein (“head”), the hepatic artery (left “ear”), and the common bile duct (right “ear”) (Figure 3). Once this sign is identified, the probe should be rotated to bring a long axis view of the portal vein. The common bile duct will run anterior and parallel to the portal vein. The duct should measure less than 4 to 6 mm in diameter; however, in patients older than age 60 years, this range should be adjusted to allow an additional 1 mm per decade).

Summary

Abdominal pain is a common presenting complaint in the ED. Ultrasound is particularly useful in evaluating right upper quadrant pain. This ultrasound is easy to learn and, with practice, it can decrease time to diagnosis and improve the length of a patient’s stay in the ED.

Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Reference

- Blaivas M, Harwood RA, Lambert MJ. Decreasing length of stay with emergency ultrasound examination of the gallbladder. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(10):1020-1023.

Additional examples of ultrasound imaging and videos of the upper right abdominal quadrant may be accessed at https://vimeo.com/136832371

When evaluating patients presenting with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, there are several imaging modalities to consider—ultrasound, computed tomography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan. In addition to the many benefits to choosing bedside ultrasound as an initial modality, it also carries the least amount of imaging-associated risks (eg, lowest amount of radiation, no exposure to ionizing radiation or radionucleotides). Moreover, not only can bedside ultrasound decrease the time to diagnosis, but it also reduces the length of patient stay by an average of 1 hour.1

The patient is typically placed in the recumbent position, but in certain cases, placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position may improve visualization. The scan should begin by placing the low-frequency probe in a sagittal orientation with the indicator marker pointed toward the head. Starting in the midline subxiphoid position, the clinician should angle the probe underneath the costal margin and then slide it to the patient’s right side. This will typically bring the gallbladder into view. If the gallbladder is not identified in this first pass, a second sweep across the ribs can be performed. If the gallbladder is still not in view, the clinician should then try placing the probe on the patient’s right side near the midaxillary line and fanning though the liver in a coronal plane (Figure 1).

Once the gallbladder is located, it is important to ensure that both the long and short axis planes are completely visualized. This can be accomplished by rotating the probe. There are several techniques to confirm that the structure in view is the gallbladder. One approach is to use the color-flow option, which can help differentiate vascular structures from the gallbladder. The gallbladder, which is connected to the portal vein by the main lobar fissure, will appear as an exclamation point on the ultrasound image (Figure 2).

In ultrasound, pericholecystic fluid will appear around the gallbladder as small black triangular shapes. Gallstones have a hyperechoic anterior rim with posterior dark shadowing. Typically, gallstones are freely mobile unless they are stuck in the neck of the gallbladder, in which case, there is heightened concern for cholecystitis (Figure 2).

Visualization of the common bile duct can be challenging. Fortunately, most cases of acute cholecystitis can be diagnosed even without visualization of the common bile duct. When attempting visualization, however, the common bile duct can be found by tracing the main lobar fissure to the portal vein. The portal triad (commonly referred to as the “Mickey Mouse” sign) comprises the portal vein (“head”), the hepatic artery (left “ear”), and the common bile duct (right “ear”) (Figure 3). Once this sign is identified, the probe should be rotated to bring a long axis view of the portal vein. The common bile duct will run anterior and parallel to the portal vein. The duct should measure less than 4 to 6 mm in diameter; however, in patients older than age 60 years, this range should be adjusted to allow an additional 1 mm per decade).

Summary

Abdominal pain is a common presenting complaint in the ED. Ultrasound is particularly useful in evaluating right upper quadrant pain. This ultrasound is easy to learn and, with practice, it can decrease time to diagnosis and improve the length of a patient’s stay in the ED.

Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

When evaluating patients presenting with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, there are several imaging modalities to consider—ultrasound, computed tomography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan. In addition to the many benefits to choosing bedside ultrasound as an initial modality, it also carries the least amount of imaging-associated risks (eg, lowest amount of radiation, no exposure to ionizing radiation or radionucleotides). Moreover, not only can bedside ultrasound decrease the time to diagnosis, but it also reduces the length of patient stay by an average of 1 hour.1

The patient is typically placed in the recumbent position, but in certain cases, placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position may improve visualization. The scan should begin by placing the low-frequency probe in a sagittal orientation with the indicator marker pointed toward the head. Starting in the midline subxiphoid position, the clinician should angle the probe underneath the costal margin and then slide it to the patient’s right side. This will typically bring the gallbladder into view. If the gallbladder is not identified in this first pass, a second sweep across the ribs can be performed. If the gallbladder is still not in view, the clinician should then try placing the probe on the patient’s right side near the midaxillary line and fanning though the liver in a coronal plane (Figure 1).

Once the gallbladder is located, it is important to ensure that both the long and short axis planes are completely visualized. This can be accomplished by rotating the probe. There are several techniques to confirm that the structure in view is the gallbladder. One approach is to use the color-flow option, which can help differentiate vascular structures from the gallbladder. The gallbladder, which is connected to the portal vein by the main lobar fissure, will appear as an exclamation point on the ultrasound image (Figure 2).

In ultrasound, pericholecystic fluid will appear around the gallbladder as small black triangular shapes. Gallstones have a hyperechoic anterior rim with posterior dark shadowing. Typically, gallstones are freely mobile unless they are stuck in the neck of the gallbladder, in which case, there is heightened concern for cholecystitis (Figure 2).

Visualization of the common bile duct can be challenging. Fortunately, most cases of acute cholecystitis can be diagnosed even without visualization of the common bile duct. When attempting visualization, however, the common bile duct can be found by tracing the main lobar fissure to the portal vein. The portal triad (commonly referred to as the “Mickey Mouse” sign) comprises the portal vein (“head”), the hepatic artery (left “ear”), and the common bile duct (right “ear”) (Figure 3). Once this sign is identified, the probe should be rotated to bring a long axis view of the portal vein. The common bile duct will run anterior and parallel to the portal vein. The duct should measure less than 4 to 6 mm in diameter; however, in patients older than age 60 years, this range should be adjusted to allow an additional 1 mm per decade).

Summary

Abdominal pain is a common presenting complaint in the ED. Ultrasound is particularly useful in evaluating right upper quadrant pain. This ultrasound is easy to learn and, with practice, it can decrease time to diagnosis and improve the length of a patient’s stay in the ED.

Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Reference

- Blaivas M, Harwood RA, Lambert MJ. Decreasing length of stay with emergency ultrasound examination of the gallbladder. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(10):1020-1023.

Additional examples of ultrasound imaging and videos of the upper right abdominal quadrant may be accessed at https://vimeo.com/136832371

Reference

- Blaivas M, Harwood RA, Lambert MJ. Decreasing length of stay with emergency ultrasound examination of the gallbladder. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(10):1020-1023.

Additional examples of ultrasound imaging and videos of the upper right abdominal quadrant may be accessed at https://vimeo.com/136832371