User login

In August 2014, we first heard of increased pediatric cases of severe respiratory tract disease, many requiring management in the ICU, and of acute flaccid myelitis/paralysis (AFM) of unknown etiology from many states across the United States. Concurrently with this outbreak in the United States, similar clinical cases were reported in Canada and Europe. Subsequently, enterovirus D68 was confirmed in some, but not all, of the paralyzed children. Although new to many of us, enterovirus D68 was already known as an atypical enterovirus sharing many of its structural and chemical properties with rhinovirus. For example, it most often was reported from respiratory samples and less common from stool samples. It also had been associated with clusters of respiratory disease since 2000 and a 2008 case of fatal AFM.

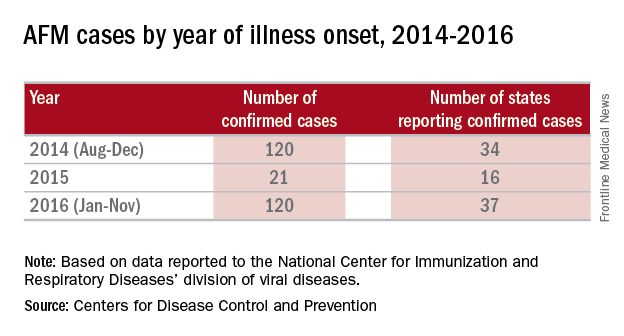

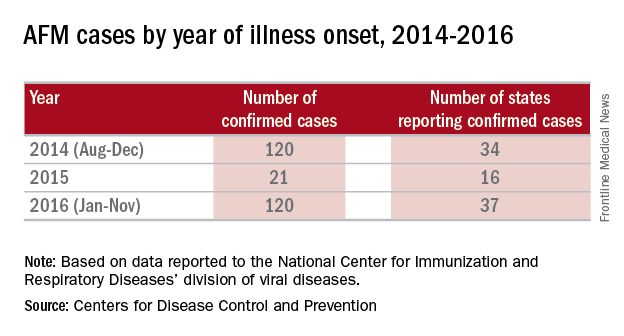

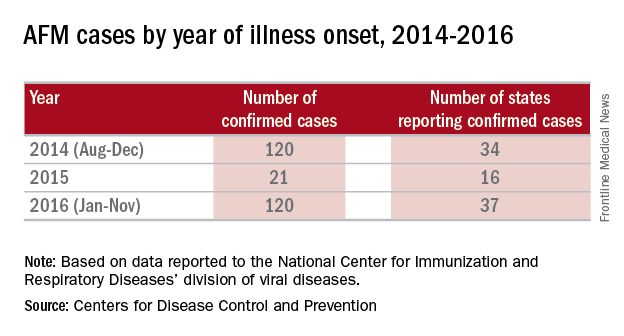

There were 120 cases of AFM, coinciding with the nationwide outbreak of enteroviral D68 disease, reported in 2014. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has evaluated the cerebrospinal fluid in many of these cases, and no pathogen has consistently been detected. The children were mostly school age, aged 7-11 years, presented with acute, febrile respiratory illness followed by acute onset of cranial nerve dysfunction or flaccid paralysis of one or more limbs. The CSF revealed mild pleocytosis, most often with mild elevation of protein and a normal glucose. However, the MRI was distinctly abnormal with focal lesion in the cranial nerve nuclei (in those with bulbar dysfunction) and/or in the anterior horn or spinal cord gray matter. Long-term prognosis is unknown, although most patients have persistent weakness, despite some improvement, to date.

In 2016, the CDC has reported an increase in cases after a decline in 2015 despite the absence of epidemic respiratory tract disease in the United States from enterovirus D68. In the Netherlands, an increase in respiratory disease from enterovirus D68 in children and adults also has been reported since June 2016. Respiratory disease has been observed in children as young as 3 months of age, and most of the children have underlying comorbidity, many with asthma or other pulmonary conditions. Thirteen of 17 (77%) cases in children have required ICU admission, while most of the adult cases were mild and influenzalike. One child developed bulbar dysfunction and limb weakness.

Enterovirus D68 infection should be suspected in children with moderate to severe respiratory tract infection or acute onset bulbar or flaccid paralysis of unknown etiology, especially in summer and fall. In such cases, respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal or oral swabs or wash, tracheal secretions or bronchoalveolar lavage) should be obtained. Increasingly, hospitals and laboratories can perform multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing for enterovirus/rhinovirus. However, most do not determine the specific enterovirus. CDC and some state health departments use real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which enables reporting of specific enterovirus species within days. CDC recommends that clinicians consider enterovirus D68 testing for children with unknown, severe respiratory illness or AFM. Details for sending specimens should be available from your state’s Department of Public Health website or the CDC.

Prevention strategies may be critical for limiting the spread of enterovirus D68 in the community. The CDC recommends:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for 20 seconds.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth with unwashed hands.

- Avoid close contact such as kissing, hugging, and sharing cups with people who are ill.

- Cover your coughs and sneezes with a tissue or shirt sleeve, not your hands.

- Clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces, such as toys and doorknobs, especially if someone is sick.

- Stay home when you are ill.

In 2014, it was speculated that the epidemic might have been a one-time event. It now appears more likely that enterovirus D68 activity has been increasing since 2000, and that children and immunocompromised hosts will be at greatest risk because of a lack of neutralizing antibody. Ongoing enterovirus surveillance will be critical to understand the potential for severe respiratory disease as will the development of new and effective antivirals. A vaccine for enterovirus 71 recently demonstrated efficacy against hand, foot, and mouth disease in children and may provide insights into the development of vaccines against enterovirus D68.

References

Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 May;16(5):e64-75

Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Jan;23(1):140-3.

J Med Virol. 2016 May;88(5):739-45

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

In August 2014, we first heard of increased pediatric cases of severe respiratory tract disease, many requiring management in the ICU, and of acute flaccid myelitis/paralysis (AFM) of unknown etiology from many states across the United States. Concurrently with this outbreak in the United States, similar clinical cases were reported in Canada and Europe. Subsequently, enterovirus D68 was confirmed in some, but not all, of the paralyzed children. Although new to many of us, enterovirus D68 was already known as an atypical enterovirus sharing many of its structural and chemical properties with rhinovirus. For example, it most often was reported from respiratory samples and less common from stool samples. It also had been associated with clusters of respiratory disease since 2000 and a 2008 case of fatal AFM.

There were 120 cases of AFM, coinciding with the nationwide outbreak of enteroviral D68 disease, reported in 2014. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has evaluated the cerebrospinal fluid in many of these cases, and no pathogen has consistently been detected. The children were mostly school age, aged 7-11 years, presented with acute, febrile respiratory illness followed by acute onset of cranial nerve dysfunction or flaccid paralysis of one or more limbs. The CSF revealed mild pleocytosis, most often with mild elevation of protein and a normal glucose. However, the MRI was distinctly abnormal with focal lesion in the cranial nerve nuclei (in those with bulbar dysfunction) and/or in the anterior horn or spinal cord gray matter. Long-term prognosis is unknown, although most patients have persistent weakness, despite some improvement, to date.

In 2016, the CDC has reported an increase in cases after a decline in 2015 despite the absence of epidemic respiratory tract disease in the United States from enterovirus D68. In the Netherlands, an increase in respiratory disease from enterovirus D68 in children and adults also has been reported since June 2016. Respiratory disease has been observed in children as young as 3 months of age, and most of the children have underlying comorbidity, many with asthma or other pulmonary conditions. Thirteen of 17 (77%) cases in children have required ICU admission, while most of the adult cases were mild and influenzalike. One child developed bulbar dysfunction and limb weakness.

Enterovirus D68 infection should be suspected in children with moderate to severe respiratory tract infection or acute onset bulbar or flaccid paralysis of unknown etiology, especially in summer and fall. In such cases, respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal or oral swabs or wash, tracheal secretions or bronchoalveolar lavage) should be obtained. Increasingly, hospitals and laboratories can perform multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing for enterovirus/rhinovirus. However, most do not determine the specific enterovirus. CDC and some state health departments use real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which enables reporting of specific enterovirus species within days. CDC recommends that clinicians consider enterovirus D68 testing for children with unknown, severe respiratory illness or AFM. Details for sending specimens should be available from your state’s Department of Public Health website or the CDC.

Prevention strategies may be critical for limiting the spread of enterovirus D68 in the community. The CDC recommends:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for 20 seconds.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth with unwashed hands.

- Avoid close contact such as kissing, hugging, and sharing cups with people who are ill.

- Cover your coughs and sneezes with a tissue or shirt sleeve, not your hands.

- Clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces, such as toys and doorknobs, especially if someone is sick.

- Stay home when you are ill.

In 2014, it was speculated that the epidemic might have been a one-time event. It now appears more likely that enterovirus D68 activity has been increasing since 2000, and that children and immunocompromised hosts will be at greatest risk because of a lack of neutralizing antibody. Ongoing enterovirus surveillance will be critical to understand the potential for severe respiratory disease as will the development of new and effective antivirals. A vaccine for enterovirus 71 recently demonstrated efficacy against hand, foot, and mouth disease in children and may provide insights into the development of vaccines against enterovirus D68.

References

Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 May;16(5):e64-75

Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Jan;23(1):140-3.

J Med Virol. 2016 May;88(5):739-45

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

In August 2014, we first heard of increased pediatric cases of severe respiratory tract disease, many requiring management in the ICU, and of acute flaccid myelitis/paralysis (AFM) of unknown etiology from many states across the United States. Concurrently with this outbreak in the United States, similar clinical cases were reported in Canada and Europe. Subsequently, enterovirus D68 was confirmed in some, but not all, of the paralyzed children. Although new to many of us, enterovirus D68 was already known as an atypical enterovirus sharing many of its structural and chemical properties with rhinovirus. For example, it most often was reported from respiratory samples and less common from stool samples. It also had been associated with clusters of respiratory disease since 2000 and a 2008 case of fatal AFM.

There were 120 cases of AFM, coinciding with the nationwide outbreak of enteroviral D68 disease, reported in 2014. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has evaluated the cerebrospinal fluid in many of these cases, and no pathogen has consistently been detected. The children were mostly school age, aged 7-11 years, presented with acute, febrile respiratory illness followed by acute onset of cranial nerve dysfunction or flaccid paralysis of one or more limbs. The CSF revealed mild pleocytosis, most often with mild elevation of protein and a normal glucose. However, the MRI was distinctly abnormal with focal lesion in the cranial nerve nuclei (in those with bulbar dysfunction) and/or in the anterior horn or spinal cord gray matter. Long-term prognosis is unknown, although most patients have persistent weakness, despite some improvement, to date.

In 2016, the CDC has reported an increase in cases after a decline in 2015 despite the absence of epidemic respiratory tract disease in the United States from enterovirus D68. In the Netherlands, an increase in respiratory disease from enterovirus D68 in children and adults also has been reported since June 2016. Respiratory disease has been observed in children as young as 3 months of age, and most of the children have underlying comorbidity, many with asthma or other pulmonary conditions. Thirteen of 17 (77%) cases in children have required ICU admission, while most of the adult cases were mild and influenzalike. One child developed bulbar dysfunction and limb weakness.

Enterovirus D68 infection should be suspected in children with moderate to severe respiratory tract infection or acute onset bulbar or flaccid paralysis of unknown etiology, especially in summer and fall. In such cases, respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal or oral swabs or wash, tracheal secretions or bronchoalveolar lavage) should be obtained. Increasingly, hospitals and laboratories can perform multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing for enterovirus/rhinovirus. However, most do not determine the specific enterovirus. CDC and some state health departments use real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which enables reporting of specific enterovirus species within days. CDC recommends that clinicians consider enterovirus D68 testing for children with unknown, severe respiratory illness or AFM. Details for sending specimens should be available from your state’s Department of Public Health website or the CDC.

Prevention strategies may be critical for limiting the spread of enterovirus D68 in the community. The CDC recommends:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for 20 seconds.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth with unwashed hands.

- Avoid close contact such as kissing, hugging, and sharing cups with people who are ill.

- Cover your coughs and sneezes with a tissue or shirt sleeve, not your hands.

- Clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces, such as toys and doorknobs, especially if someone is sick.

- Stay home when you are ill.

In 2014, it was speculated that the epidemic might have been a one-time event. It now appears more likely that enterovirus D68 activity has been increasing since 2000, and that children and immunocompromised hosts will be at greatest risk because of a lack of neutralizing antibody. Ongoing enterovirus surveillance will be critical to understand the potential for severe respiratory disease as will the development of new and effective antivirals. A vaccine for enterovirus 71 recently demonstrated efficacy against hand, foot, and mouth disease in children and may provide insights into the development of vaccines against enterovirus D68.

References

Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 May;16(5):e64-75

Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Jan;23(1):140-3.

J Med Virol. 2016 May;88(5):739-45

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].