User login

Today there are so many evidence-based drug therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that physicians treating HF patients almost don’t know what to do them.

It’s an exciting new age that way, but to many vexingly unclear how best to merge the shiny new options with mainstay regimens based on time-honored renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers.

To impart some clarity, the authors of a new HF guideline document recently took center stage at the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) annual meeting to preview their updated recommendations, with novel twists based on recent major trials, for the new age of HF pharmacotherapeutics.

The guideline committee considered the evidence base that existed “up until the end of March of this year,” Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, King’s College London, said during the presentation. The document “is now finalized, it’s with the publishers, and it will be presented in full with simultaneous publication at the ESC meeting” that starts August 27.

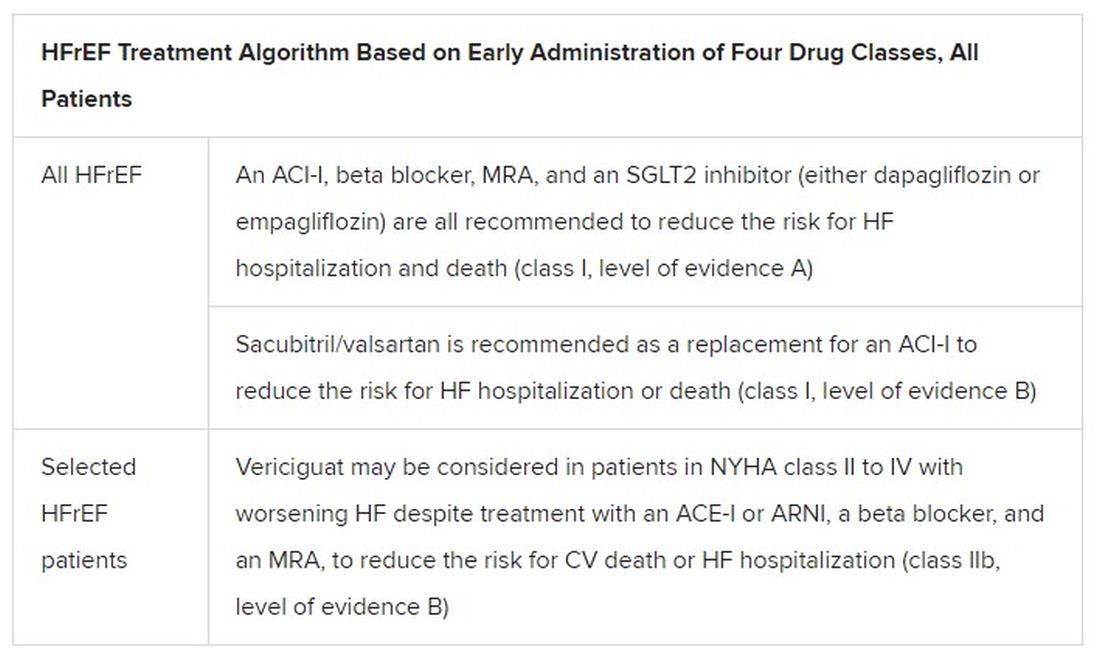

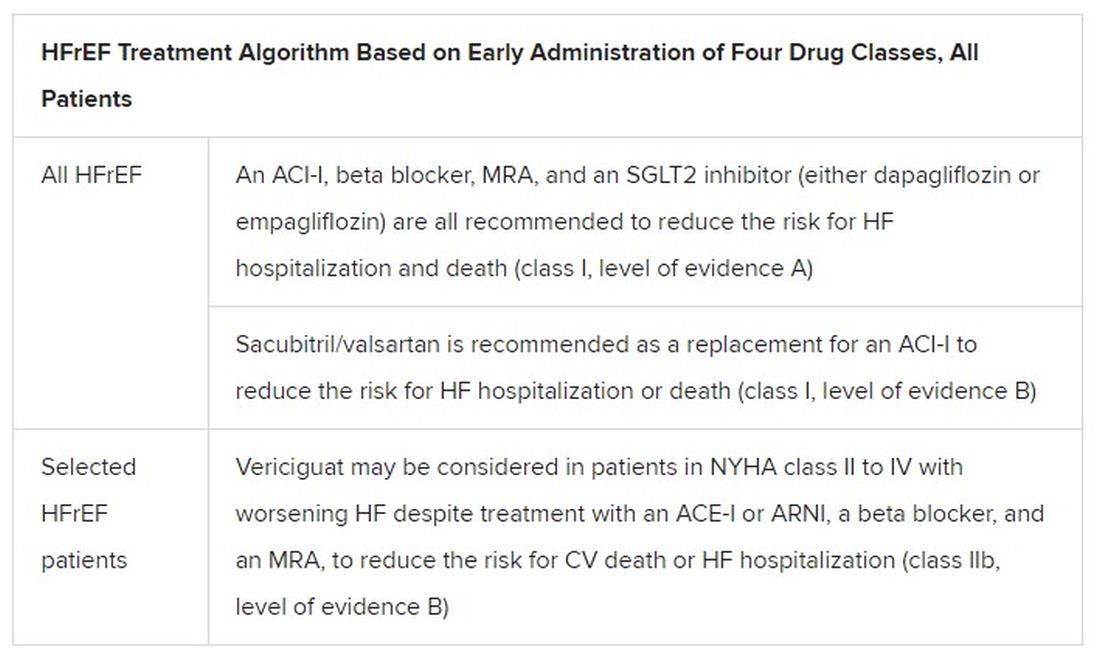

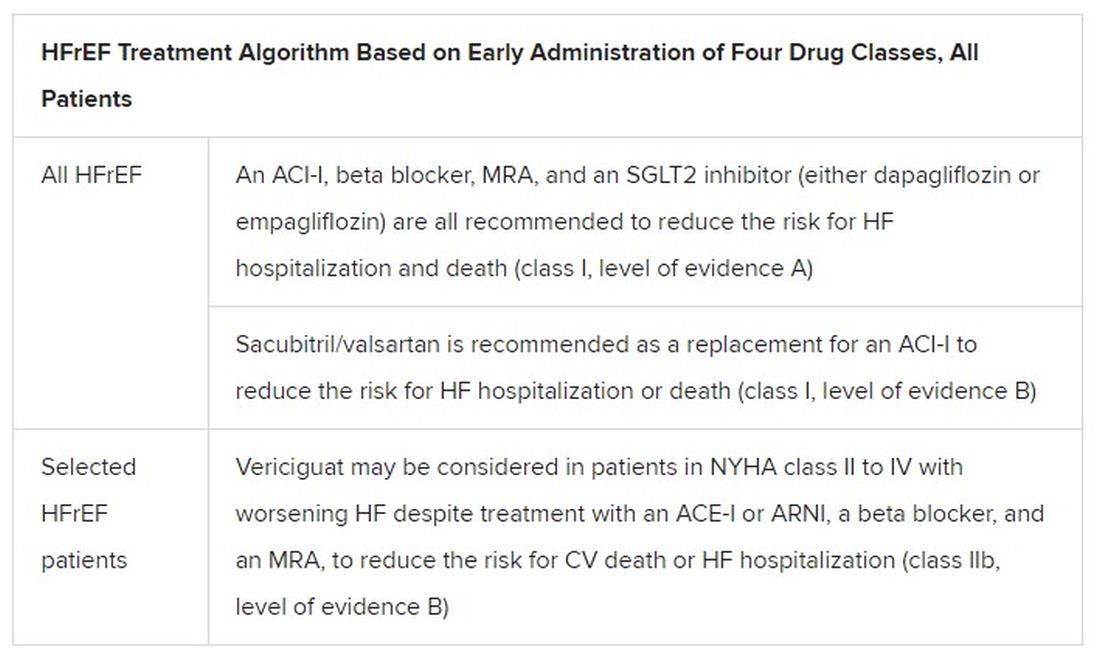

It describes a game plan, already followed by some clinicians in practice without official guidance, for initiating drugs from each of four classes in virtually all patients with HFrEF.

New indicated drugs, new perspective for HFrEF

Three of the drug categories are old acquaintances. Among them are the RAS inhibitors, which include angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The latter drugs are gaining new respect after having been underplayed in HF prescribing despite longstanding evidence of efficacy.

Completing the quartet of first-line HFrEF drug classes is a recent arrival to the HF arena, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“We now have new data and a simplified treatment algorithm for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction based on the early administration of the four major classes of drugs,” said Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy), previewing the medical-therapy portions of the new guideline at the ESC-HFA sessions, which launched virtually and live in Florence, Italy, on July 29.

The new game plan offers a simple answer to a once-common but complex question: How and in what order are the different drug classes initiated in patients with HFrEF? In the new document, the stated goal is to get them all on board expeditiously and safely, by any means possible.

The guideline writers did not specify a sequence, preferring to leave that decision to physicians, said Dr. Metra, who stated only two guiding principles. The first is to consider the patient’s unique circumstances. The order in which the drugs are introduced might vary, depending on, for example, whether the patient has low or high blood pressure or renal dysfunction.

Second, “it is very important that we try to give all four classes of drugs to the patient in the shortest time possible, because this saves lives,” he said.

That there is no recommendation on sequencing the drugs has led some to the wrong interpretation that all should be started at once, observed coauthor Javed Butler, MD, MPH, University of Mississippi, Jackson, as a panelist during the presentation. Far from it, he said. “The doctor with the patient in front of you can make the best decision. The idea here is to get all the therapies on as soon as possible, as safely as possible.”

“The order in which they are introduced is not really important,” agreed Vijay Chopra, MD, Max Super Specialty Hospital Saket, New Delhi, another coauthor on the panel. “The important thing is that at least some dose of all the four drugs needs to be introduced in the first 4-6 weeks, and then up-titrated.”

Other medical therapy can be more tailored, Dr. Metra noted, such as loop diuretics for patients with congestion, iron for those with iron deficiency, and other drugs depending on whether there is, for example, atrial fibrillation or coronary disease.

Adoption of emerging definitions

The document adopts the emerging characterization of HFrEF by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) up to 40%.

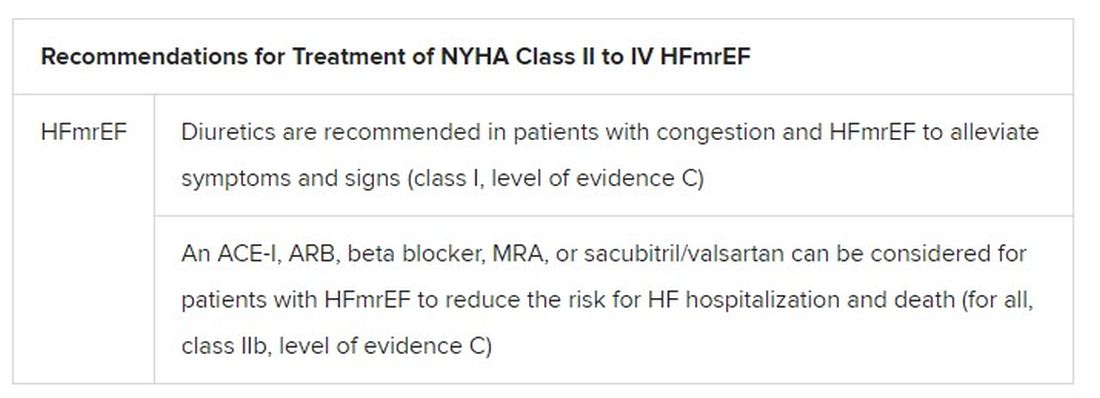

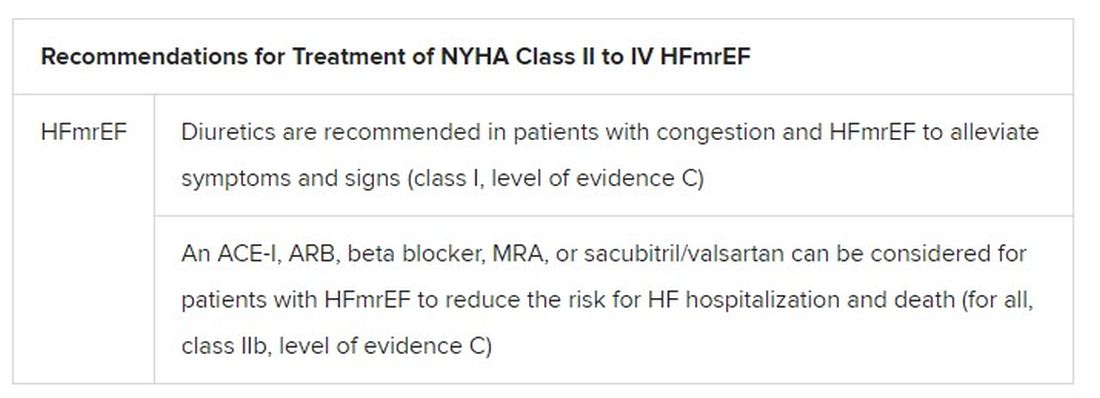

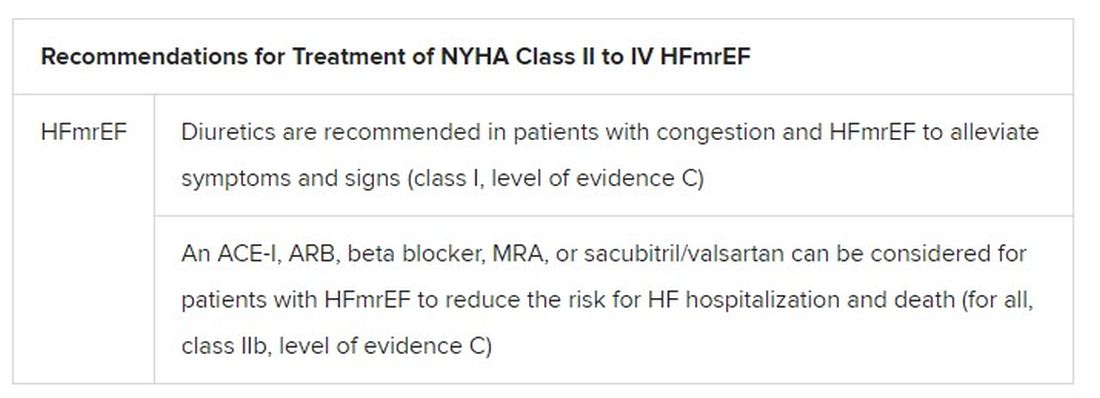

And it will leverage an expanding evidence base for medication in a segment of patients once said to have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who had therefore lacked specific, guideline-directed medical therapies. Now, patients with an LVEF of 41%-49% will be said to have HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), a tweak to the recently introduced HF with “mid-range” LVEF that is designed to assert its nature as something to treat. The new document’s HFmrEF recommendations come with various class and level-of-evidence ratings.

That leaves HFpEF to be characterized by an LVEF of 50% in combination with structural or functional abnormalities associated with LV diastolic dysfunction or raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptide levels.

The definitions are consistent with those proposed internationally by the ESC-HFA, the Heart Failure Society of America, and other groups in a statement published in March.

Expanded HFrEF med landscape

Since the 2016 ESC guideline on HF therapy, Dr. McDonagh said, “there’s been no substantial change in the evidence for many of the classical drugs that we use in heart failure. However, we had a lot of new and exciting evidence to consider,” especially in support of the SGLT2 inhibitors as one of the core medications in HFrEF.

The new data came from two controlled trials in particular. In DAPA-HF, patients with HFrEF who were initially without diabetes and who went on dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) showed a 27% drop in cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening-HF events over a median of 18 months.

“That was followed up with very concordant results with empagliflozin [Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly] in HFrEF in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial,” Dr. McDonagh said. In that trial, comparable patients who took empagliflozin showed a 25% drop in a primary endpoint similar to that in DAPA-HF over the median 16-month follow-up.

Other HFrEF recommendations are for selected patients. They include ivabradine, already in the guidelines, for patients in sinus rhythm with an elevated resting heart rate who can’t take beta-blockers for whatever reason. But, Dr. McDonagh noted, “we had some new classes of drugs to consider as well.”

In particular, the oral soluble guanylate-cyclase receptor stimulator vericiguat (Verquvo) emerged about a year ago from the VICTORIA trial as a modest success for patients with HFrEF and a previous HF hospitalization. In the trial with more than 5,000 patients, treatment with vericiguat atop standard drug and device therapy was followed by a significant 10% drop in risk for CV death or HF hospitalization.

Available now or likely to be available in the United States, the European Union, Japan, and other countries, vericiguat is recommended in the new guideline for VICTORIA-like patients who don’t adequately respond to other indicated medications.

Little for HFpEF as newly defined

“Almost nothing is new” in the guidelines for HFpEF, Dr. Metra said. The document recommends screening for and treatment of any underlying disorder and comorbidities, plus diuretics for any congestion. “That’s what we have to date.”

But that evidence base might soon change. The new HFpEF recommendations could possibly be up-staged at the ESC sessions by the August 27 scheduled presentation of EMPEROR-Preserved, a randomized test of empagliflozin in HFpEF and – it could be said – HFmrEF. The trial entered patients with chronic HF and an LVEF greater than 40%.

Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim offered the world a peek at the results, which suggest the SGLT2 inhibitor had a positive impact on the primary endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization. They announced the cursory top-line outcomes in early July as part of its regulatory obligations, noting that the trial had “met” its primary endpoint.

But many unknowns remain, including the degree of benefit and whether it varied among subgroups, and especially whether outcomes were different for HFmrEF than for HFpEF.

Upgrades for familiar agents

Still, HFmrEF gets noteworthy attention in the document. “For the first time, we have recommendations for these patients,” Dr. Metra said. “We already knew that diuretics are indicated for the treatment of congestion. But now, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid antagonists, as well as sacubitril/valsartan, may be considered to improve outcomes in these patients.” Their upgrades in the new guidelines were based on review of trials in the CHARM program and of TOPCAT and PARAGON-HF, among others, he said.

The new document also includes “treatment algorithms based on phenotypes”; that is, comorbidities and less common HF precipitants. For example, “assessment of iron status is now mandated in all patients with heart failure,” Dr. Metra said.

AFFIRM-HF is the key trial in this arena, with its more than 1,100 iron-deficient patients with LVEF less than 50% who had been recently hospitalized for HF. A year of treatment with ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject/Injectafer, Vifor) led to a 26% drop in risk for HF hospitalization, but without affecting mortality.

For those who are iron deficient, Dr. Metra said, “ferric carboxymaltose intravenously should be considered not only in patients with low ejection fraction and outpatients, but also in patients recently hospitalized for acute heart failure.”

The SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended in HFrEF patients with type 2 diabetes. And treatment with tafamidis (Vyndaqel, Pfizer) in patients with genetic or wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis gets a class I recommendation based on survival gains seen in the ATTR-ACT trial.

Also recommended is a full CV assessment for patients with cancer who are on cardiotoxic agents or otherwise might be at risk for chemotherapy cardiotoxicity. “Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors should be considered in those who develop left ventricular systolic dysfunction after anticancer therapy,” Dr. Metra said.

The ongoing pandemic made its mark on the document’s genesis, as it has with most everything else. “For better or worse, we were a ‘COVID guideline,’ ” Dr. McDonagh said. The writing committee consisted of “a large task force of 31 individuals, including two patients,” and there were “only two face-to-face meetings prior to the first wave of COVID hitting Europe.”

The committee voted on each of the recommendations, “and we had to have agreement of more than 75% of the task force to assign a class of recommendation or level of evidence,” she said. “I think we did the best we could in the circumstances. We had the benefit of many discussions over Zoom, and I think at the end of the day we have achieved a consensus.”

With such a large body of participants and the 75% threshold for agreement, “you end up with perhaps a conservative guideline. But that’s not a bad thing for clinical practice, for guidelines to be conservative,” Dr. McDonagh said. “They’re mainly concerned with looking at evidence and safety.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Today there are so many evidence-based drug therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that physicians treating HF patients almost don’t know what to do them.

It’s an exciting new age that way, but to many vexingly unclear how best to merge the shiny new options with mainstay regimens based on time-honored renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers.

To impart some clarity, the authors of a new HF guideline document recently took center stage at the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) annual meeting to preview their updated recommendations, with novel twists based on recent major trials, for the new age of HF pharmacotherapeutics.

The guideline committee considered the evidence base that existed “up until the end of March of this year,” Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, King’s College London, said during the presentation. The document “is now finalized, it’s with the publishers, and it will be presented in full with simultaneous publication at the ESC meeting” that starts August 27.

It describes a game plan, already followed by some clinicians in practice without official guidance, for initiating drugs from each of four classes in virtually all patients with HFrEF.

New indicated drugs, new perspective for HFrEF

Three of the drug categories are old acquaintances. Among them are the RAS inhibitors, which include angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The latter drugs are gaining new respect after having been underplayed in HF prescribing despite longstanding evidence of efficacy.

Completing the quartet of first-line HFrEF drug classes is a recent arrival to the HF arena, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“We now have new data and a simplified treatment algorithm for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction based on the early administration of the four major classes of drugs,” said Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy), previewing the medical-therapy portions of the new guideline at the ESC-HFA sessions, which launched virtually and live in Florence, Italy, on July 29.

The new game plan offers a simple answer to a once-common but complex question: How and in what order are the different drug classes initiated in patients with HFrEF? In the new document, the stated goal is to get them all on board expeditiously and safely, by any means possible.

The guideline writers did not specify a sequence, preferring to leave that decision to physicians, said Dr. Metra, who stated only two guiding principles. The first is to consider the patient’s unique circumstances. The order in which the drugs are introduced might vary, depending on, for example, whether the patient has low or high blood pressure or renal dysfunction.

Second, “it is very important that we try to give all four classes of drugs to the patient in the shortest time possible, because this saves lives,” he said.

That there is no recommendation on sequencing the drugs has led some to the wrong interpretation that all should be started at once, observed coauthor Javed Butler, MD, MPH, University of Mississippi, Jackson, as a panelist during the presentation. Far from it, he said. “The doctor with the patient in front of you can make the best decision. The idea here is to get all the therapies on as soon as possible, as safely as possible.”

“The order in which they are introduced is not really important,” agreed Vijay Chopra, MD, Max Super Specialty Hospital Saket, New Delhi, another coauthor on the panel. “The important thing is that at least some dose of all the four drugs needs to be introduced in the first 4-6 weeks, and then up-titrated.”

Other medical therapy can be more tailored, Dr. Metra noted, such as loop diuretics for patients with congestion, iron for those with iron deficiency, and other drugs depending on whether there is, for example, atrial fibrillation or coronary disease.

Adoption of emerging definitions

The document adopts the emerging characterization of HFrEF by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) up to 40%.

And it will leverage an expanding evidence base for medication in a segment of patients once said to have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who had therefore lacked specific, guideline-directed medical therapies. Now, patients with an LVEF of 41%-49% will be said to have HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), a tweak to the recently introduced HF with “mid-range” LVEF that is designed to assert its nature as something to treat. The new document’s HFmrEF recommendations come with various class and level-of-evidence ratings.

That leaves HFpEF to be characterized by an LVEF of 50% in combination with structural or functional abnormalities associated with LV diastolic dysfunction or raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptide levels.

The definitions are consistent with those proposed internationally by the ESC-HFA, the Heart Failure Society of America, and other groups in a statement published in March.

Expanded HFrEF med landscape

Since the 2016 ESC guideline on HF therapy, Dr. McDonagh said, “there’s been no substantial change in the evidence for many of the classical drugs that we use in heart failure. However, we had a lot of new and exciting evidence to consider,” especially in support of the SGLT2 inhibitors as one of the core medications in HFrEF.

The new data came from two controlled trials in particular. In DAPA-HF, patients with HFrEF who were initially without diabetes and who went on dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) showed a 27% drop in cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening-HF events over a median of 18 months.

“That was followed up with very concordant results with empagliflozin [Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly] in HFrEF in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial,” Dr. McDonagh said. In that trial, comparable patients who took empagliflozin showed a 25% drop in a primary endpoint similar to that in DAPA-HF over the median 16-month follow-up.

Other HFrEF recommendations are for selected patients. They include ivabradine, already in the guidelines, for patients in sinus rhythm with an elevated resting heart rate who can’t take beta-blockers for whatever reason. But, Dr. McDonagh noted, “we had some new classes of drugs to consider as well.”

In particular, the oral soluble guanylate-cyclase receptor stimulator vericiguat (Verquvo) emerged about a year ago from the VICTORIA trial as a modest success for patients with HFrEF and a previous HF hospitalization. In the trial with more than 5,000 patients, treatment with vericiguat atop standard drug and device therapy was followed by a significant 10% drop in risk for CV death or HF hospitalization.

Available now or likely to be available in the United States, the European Union, Japan, and other countries, vericiguat is recommended in the new guideline for VICTORIA-like patients who don’t adequately respond to other indicated medications.

Little for HFpEF as newly defined

“Almost nothing is new” in the guidelines for HFpEF, Dr. Metra said. The document recommends screening for and treatment of any underlying disorder and comorbidities, plus diuretics for any congestion. “That’s what we have to date.”

But that evidence base might soon change. The new HFpEF recommendations could possibly be up-staged at the ESC sessions by the August 27 scheduled presentation of EMPEROR-Preserved, a randomized test of empagliflozin in HFpEF and – it could be said – HFmrEF. The trial entered patients with chronic HF and an LVEF greater than 40%.

Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim offered the world a peek at the results, which suggest the SGLT2 inhibitor had a positive impact on the primary endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization. They announced the cursory top-line outcomes in early July as part of its regulatory obligations, noting that the trial had “met” its primary endpoint.

But many unknowns remain, including the degree of benefit and whether it varied among subgroups, and especially whether outcomes were different for HFmrEF than for HFpEF.

Upgrades for familiar agents

Still, HFmrEF gets noteworthy attention in the document. “For the first time, we have recommendations for these patients,” Dr. Metra said. “We already knew that diuretics are indicated for the treatment of congestion. But now, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid antagonists, as well as sacubitril/valsartan, may be considered to improve outcomes in these patients.” Their upgrades in the new guidelines were based on review of trials in the CHARM program and of TOPCAT and PARAGON-HF, among others, he said.

The new document also includes “treatment algorithms based on phenotypes”; that is, comorbidities and less common HF precipitants. For example, “assessment of iron status is now mandated in all patients with heart failure,” Dr. Metra said.

AFFIRM-HF is the key trial in this arena, with its more than 1,100 iron-deficient patients with LVEF less than 50% who had been recently hospitalized for HF. A year of treatment with ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject/Injectafer, Vifor) led to a 26% drop in risk for HF hospitalization, but without affecting mortality.

For those who are iron deficient, Dr. Metra said, “ferric carboxymaltose intravenously should be considered not only in patients with low ejection fraction and outpatients, but also in patients recently hospitalized for acute heart failure.”

The SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended in HFrEF patients with type 2 diabetes. And treatment with tafamidis (Vyndaqel, Pfizer) in patients with genetic or wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis gets a class I recommendation based on survival gains seen in the ATTR-ACT trial.

Also recommended is a full CV assessment for patients with cancer who are on cardiotoxic agents or otherwise might be at risk for chemotherapy cardiotoxicity. “Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors should be considered in those who develop left ventricular systolic dysfunction after anticancer therapy,” Dr. Metra said.

The ongoing pandemic made its mark on the document’s genesis, as it has with most everything else. “For better or worse, we were a ‘COVID guideline,’ ” Dr. McDonagh said. The writing committee consisted of “a large task force of 31 individuals, including two patients,” and there were “only two face-to-face meetings prior to the first wave of COVID hitting Europe.”

The committee voted on each of the recommendations, “and we had to have agreement of more than 75% of the task force to assign a class of recommendation or level of evidence,” she said. “I think we did the best we could in the circumstances. We had the benefit of many discussions over Zoom, and I think at the end of the day we have achieved a consensus.”

With such a large body of participants and the 75% threshold for agreement, “you end up with perhaps a conservative guideline. But that’s not a bad thing for clinical practice, for guidelines to be conservative,” Dr. McDonagh said. “They’re mainly concerned with looking at evidence and safety.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Today there are so many evidence-based drug therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that physicians treating HF patients almost don’t know what to do them.

It’s an exciting new age that way, but to many vexingly unclear how best to merge the shiny new options with mainstay regimens based on time-honored renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers.

To impart some clarity, the authors of a new HF guideline document recently took center stage at the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) annual meeting to preview their updated recommendations, with novel twists based on recent major trials, for the new age of HF pharmacotherapeutics.

The guideline committee considered the evidence base that existed “up until the end of March of this year,” Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, King’s College London, said during the presentation. The document “is now finalized, it’s with the publishers, and it will be presented in full with simultaneous publication at the ESC meeting” that starts August 27.

It describes a game plan, already followed by some clinicians in practice without official guidance, for initiating drugs from each of four classes in virtually all patients with HFrEF.

New indicated drugs, new perspective for HFrEF

Three of the drug categories are old acquaintances. Among them are the RAS inhibitors, which include angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The latter drugs are gaining new respect after having been underplayed in HF prescribing despite longstanding evidence of efficacy.

Completing the quartet of first-line HFrEF drug classes is a recent arrival to the HF arena, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“We now have new data and a simplified treatment algorithm for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction based on the early administration of the four major classes of drugs,” said Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy), previewing the medical-therapy portions of the new guideline at the ESC-HFA sessions, which launched virtually and live in Florence, Italy, on July 29.

The new game plan offers a simple answer to a once-common but complex question: How and in what order are the different drug classes initiated in patients with HFrEF? In the new document, the stated goal is to get them all on board expeditiously and safely, by any means possible.

The guideline writers did not specify a sequence, preferring to leave that decision to physicians, said Dr. Metra, who stated only two guiding principles. The first is to consider the patient’s unique circumstances. The order in which the drugs are introduced might vary, depending on, for example, whether the patient has low or high blood pressure or renal dysfunction.

Second, “it is very important that we try to give all four classes of drugs to the patient in the shortest time possible, because this saves lives,” he said.

That there is no recommendation on sequencing the drugs has led some to the wrong interpretation that all should be started at once, observed coauthor Javed Butler, MD, MPH, University of Mississippi, Jackson, as a panelist during the presentation. Far from it, he said. “The doctor with the patient in front of you can make the best decision. The idea here is to get all the therapies on as soon as possible, as safely as possible.”

“The order in which they are introduced is not really important,” agreed Vijay Chopra, MD, Max Super Specialty Hospital Saket, New Delhi, another coauthor on the panel. “The important thing is that at least some dose of all the four drugs needs to be introduced in the first 4-6 weeks, and then up-titrated.”

Other medical therapy can be more tailored, Dr. Metra noted, such as loop diuretics for patients with congestion, iron for those with iron deficiency, and other drugs depending on whether there is, for example, atrial fibrillation or coronary disease.

Adoption of emerging definitions

The document adopts the emerging characterization of HFrEF by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) up to 40%.

And it will leverage an expanding evidence base for medication in a segment of patients once said to have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who had therefore lacked specific, guideline-directed medical therapies. Now, patients with an LVEF of 41%-49% will be said to have HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), a tweak to the recently introduced HF with “mid-range” LVEF that is designed to assert its nature as something to treat. The new document’s HFmrEF recommendations come with various class and level-of-evidence ratings.

That leaves HFpEF to be characterized by an LVEF of 50% in combination with structural or functional abnormalities associated with LV diastolic dysfunction or raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptide levels.

The definitions are consistent with those proposed internationally by the ESC-HFA, the Heart Failure Society of America, and other groups in a statement published in March.

Expanded HFrEF med landscape

Since the 2016 ESC guideline on HF therapy, Dr. McDonagh said, “there’s been no substantial change in the evidence for many of the classical drugs that we use in heart failure. However, we had a lot of new and exciting evidence to consider,” especially in support of the SGLT2 inhibitors as one of the core medications in HFrEF.

The new data came from two controlled trials in particular. In DAPA-HF, patients with HFrEF who were initially without diabetes and who went on dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) showed a 27% drop in cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening-HF events over a median of 18 months.

“That was followed up with very concordant results with empagliflozin [Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly] in HFrEF in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial,” Dr. McDonagh said. In that trial, comparable patients who took empagliflozin showed a 25% drop in a primary endpoint similar to that in DAPA-HF over the median 16-month follow-up.

Other HFrEF recommendations are for selected patients. They include ivabradine, already in the guidelines, for patients in sinus rhythm with an elevated resting heart rate who can’t take beta-blockers for whatever reason. But, Dr. McDonagh noted, “we had some new classes of drugs to consider as well.”

In particular, the oral soluble guanylate-cyclase receptor stimulator vericiguat (Verquvo) emerged about a year ago from the VICTORIA trial as a modest success for patients with HFrEF and a previous HF hospitalization. In the trial with more than 5,000 patients, treatment with vericiguat atop standard drug and device therapy was followed by a significant 10% drop in risk for CV death or HF hospitalization.

Available now or likely to be available in the United States, the European Union, Japan, and other countries, vericiguat is recommended in the new guideline for VICTORIA-like patients who don’t adequately respond to other indicated medications.

Little for HFpEF as newly defined

“Almost nothing is new” in the guidelines for HFpEF, Dr. Metra said. The document recommends screening for and treatment of any underlying disorder and comorbidities, plus diuretics for any congestion. “That’s what we have to date.”

But that evidence base might soon change. The new HFpEF recommendations could possibly be up-staged at the ESC sessions by the August 27 scheduled presentation of EMPEROR-Preserved, a randomized test of empagliflozin in HFpEF and – it could be said – HFmrEF. The trial entered patients with chronic HF and an LVEF greater than 40%.

Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim offered the world a peek at the results, which suggest the SGLT2 inhibitor had a positive impact on the primary endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization. They announced the cursory top-line outcomes in early July as part of its regulatory obligations, noting that the trial had “met” its primary endpoint.

But many unknowns remain, including the degree of benefit and whether it varied among subgroups, and especially whether outcomes were different for HFmrEF than for HFpEF.

Upgrades for familiar agents

Still, HFmrEF gets noteworthy attention in the document. “For the first time, we have recommendations for these patients,” Dr. Metra said. “We already knew that diuretics are indicated for the treatment of congestion. But now, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid antagonists, as well as sacubitril/valsartan, may be considered to improve outcomes in these patients.” Their upgrades in the new guidelines were based on review of trials in the CHARM program and of TOPCAT and PARAGON-HF, among others, he said.

The new document also includes “treatment algorithms based on phenotypes”; that is, comorbidities and less common HF precipitants. For example, “assessment of iron status is now mandated in all patients with heart failure,” Dr. Metra said.

AFFIRM-HF is the key trial in this arena, with its more than 1,100 iron-deficient patients with LVEF less than 50% who had been recently hospitalized for HF. A year of treatment with ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject/Injectafer, Vifor) led to a 26% drop in risk for HF hospitalization, but without affecting mortality.

For those who are iron deficient, Dr. Metra said, “ferric carboxymaltose intravenously should be considered not only in patients with low ejection fraction and outpatients, but also in patients recently hospitalized for acute heart failure.”

The SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended in HFrEF patients with type 2 diabetes. And treatment with tafamidis (Vyndaqel, Pfizer) in patients with genetic or wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis gets a class I recommendation based on survival gains seen in the ATTR-ACT trial.

Also recommended is a full CV assessment for patients with cancer who are on cardiotoxic agents or otherwise might be at risk for chemotherapy cardiotoxicity. “Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors should be considered in those who develop left ventricular systolic dysfunction after anticancer therapy,” Dr. Metra said.

The ongoing pandemic made its mark on the document’s genesis, as it has with most everything else. “For better or worse, we were a ‘COVID guideline,’ ” Dr. McDonagh said. The writing committee consisted of “a large task force of 31 individuals, including two patients,” and there were “only two face-to-face meetings prior to the first wave of COVID hitting Europe.”

The committee voted on each of the recommendations, “and we had to have agreement of more than 75% of the task force to assign a class of recommendation or level of evidence,” she said. “I think we did the best we could in the circumstances. We had the benefit of many discussions over Zoom, and I think at the end of the day we have achieved a consensus.”

With such a large body of participants and the 75% threshold for agreement, “you end up with perhaps a conservative guideline. But that’s not a bad thing for clinical practice, for guidelines to be conservative,” Dr. McDonagh said. “They’re mainly concerned with looking at evidence and safety.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.