User login

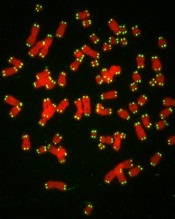

WASHINGTON, DC—Telomere length may predict cancer risk and could be a target for future therapies, according to research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

The study suggests that, overall, longer-than-expected telomeres are associated with an increased risk of cancer.

However, investigators also found an increased risk of certain cancers, including leukemia, among patients who had very short or very long telomeres.

“Telomeres and cancer clearly have a complex relationship,” said study investigator Jian-Min Yuan, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute in Pennsylvania.

“Our hope is that by understanding this relationship, we may be able to predict which people are most likely to develop certain cancers so they can take preventive measures and perhaps be screened more often, as well as develop therapies to help our DNA keep or return its telomeres to a healthy length.”

Dr Yuan and his colleagues presented their research as abstract 2267/21.*

The team analyzed blood samples and health data on 26,540 individuals enrolled in the Singapore Chinese Health Study, which has followed the health outcomes of participants since 1993. As of the end of 2015, 4060 participants had developed cancer (77 with leukemia).

The investigators divided participants into 5 groups, based on the length of their telomeres.

The group with the longest telomeres (quartile 5) had a significantly higher risk of developing any cancer than the group with the shortest telomeres (quartile 1), after taking into account the effects of age, sex, education, body mass index, smoking habits, and alcohol consumption. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.33 (P<0.0001).

In particular, the group with the longest telomeres had a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer (HR=1.37, P=0.010), breast cancer (HR=1.39, P=0.007), prostate cancer (HR=1.55, P=0.011), and pancreatic cancer (HR=2.58, P=0.009).

On the other hand, the risk of liver cancer decreased as telomere length increased. The HR was 0.72 for patients in quartile 5 compared to those in quartile 1 (Plinear=0.056).

The risk of 3 cancers was greatest for both the groups with extremely short and extremely long telomeres—quartiles 1 and 5, respectively.

For leukemia, the HR was 2.15 for quartile 1 and 1.68 for quartile 5, when compared to quartile 3 (Pnon-linear=0.015).

For bladder cancer, the HRs were 1.72 and 2.17, respectively (Pnon-linear=0.01). And for stomach cancer, the HRs were 1.63 and 1.55, respectively (Pnon-linear=0.020).

“We had the idea for this study more than 7 years ago, but it took the laboratory 3 months to finish quantifying telomere length for just 100 samples, which was not enough to draw any meaningful conclusions,” Dr Yuan said.

“Not even a decade later, we’ve been able to run nearly 30,000 samples in a year and draw these really robust insights, showing how far technology has come. Even more complicated will be linking telomere length to genome-wide analyses, which is on the horizon. We’re on the cusp of gaining a truly remarkable understanding of the complicated biological phenomena that lead to cancer.” ![]()

*The presentation differed from the abstract.

WASHINGTON, DC—Telomere length may predict cancer risk and could be a target for future therapies, according to research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

The study suggests that, overall, longer-than-expected telomeres are associated with an increased risk of cancer.

However, investigators also found an increased risk of certain cancers, including leukemia, among patients who had very short or very long telomeres.

“Telomeres and cancer clearly have a complex relationship,” said study investigator Jian-Min Yuan, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute in Pennsylvania.

“Our hope is that by understanding this relationship, we may be able to predict which people are most likely to develop certain cancers so they can take preventive measures and perhaps be screened more often, as well as develop therapies to help our DNA keep or return its telomeres to a healthy length.”

Dr Yuan and his colleagues presented their research as abstract 2267/21.*

The team analyzed blood samples and health data on 26,540 individuals enrolled in the Singapore Chinese Health Study, which has followed the health outcomes of participants since 1993. As of the end of 2015, 4060 participants had developed cancer (77 with leukemia).

The investigators divided participants into 5 groups, based on the length of their telomeres.

The group with the longest telomeres (quartile 5) had a significantly higher risk of developing any cancer than the group with the shortest telomeres (quartile 1), after taking into account the effects of age, sex, education, body mass index, smoking habits, and alcohol consumption. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.33 (P<0.0001).

In particular, the group with the longest telomeres had a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer (HR=1.37, P=0.010), breast cancer (HR=1.39, P=0.007), prostate cancer (HR=1.55, P=0.011), and pancreatic cancer (HR=2.58, P=0.009).

On the other hand, the risk of liver cancer decreased as telomere length increased. The HR was 0.72 for patients in quartile 5 compared to those in quartile 1 (Plinear=0.056).

The risk of 3 cancers was greatest for both the groups with extremely short and extremely long telomeres—quartiles 1 and 5, respectively.

For leukemia, the HR was 2.15 for quartile 1 and 1.68 for quartile 5, when compared to quartile 3 (Pnon-linear=0.015).

For bladder cancer, the HRs were 1.72 and 2.17, respectively (Pnon-linear=0.01). And for stomach cancer, the HRs were 1.63 and 1.55, respectively (Pnon-linear=0.020).

“We had the idea for this study more than 7 years ago, but it took the laboratory 3 months to finish quantifying telomere length for just 100 samples, which was not enough to draw any meaningful conclusions,” Dr Yuan said.

“Not even a decade later, we’ve been able to run nearly 30,000 samples in a year and draw these really robust insights, showing how far technology has come. Even more complicated will be linking telomere length to genome-wide analyses, which is on the horizon. We’re on the cusp of gaining a truly remarkable understanding of the complicated biological phenomena that lead to cancer.” ![]()

*The presentation differed from the abstract.

WASHINGTON, DC—Telomere length may predict cancer risk and could be a target for future therapies, according to research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

The study suggests that, overall, longer-than-expected telomeres are associated with an increased risk of cancer.

However, investigators also found an increased risk of certain cancers, including leukemia, among patients who had very short or very long telomeres.

“Telomeres and cancer clearly have a complex relationship,” said study investigator Jian-Min Yuan, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute in Pennsylvania.

“Our hope is that by understanding this relationship, we may be able to predict which people are most likely to develop certain cancers so they can take preventive measures and perhaps be screened more often, as well as develop therapies to help our DNA keep or return its telomeres to a healthy length.”

Dr Yuan and his colleagues presented their research as abstract 2267/21.*

The team analyzed blood samples and health data on 26,540 individuals enrolled in the Singapore Chinese Health Study, which has followed the health outcomes of participants since 1993. As of the end of 2015, 4060 participants had developed cancer (77 with leukemia).

The investigators divided participants into 5 groups, based on the length of their telomeres.

The group with the longest telomeres (quartile 5) had a significantly higher risk of developing any cancer than the group with the shortest telomeres (quartile 1), after taking into account the effects of age, sex, education, body mass index, smoking habits, and alcohol consumption. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.33 (P<0.0001).

In particular, the group with the longest telomeres had a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer (HR=1.37, P=0.010), breast cancer (HR=1.39, P=0.007), prostate cancer (HR=1.55, P=0.011), and pancreatic cancer (HR=2.58, P=0.009).

On the other hand, the risk of liver cancer decreased as telomere length increased. The HR was 0.72 for patients in quartile 5 compared to those in quartile 1 (Plinear=0.056).

The risk of 3 cancers was greatest for both the groups with extremely short and extremely long telomeres—quartiles 1 and 5, respectively.

For leukemia, the HR was 2.15 for quartile 1 and 1.68 for quartile 5, when compared to quartile 3 (Pnon-linear=0.015).

For bladder cancer, the HRs were 1.72 and 2.17, respectively (Pnon-linear=0.01). And for stomach cancer, the HRs were 1.63 and 1.55, respectively (Pnon-linear=0.020).

“We had the idea for this study more than 7 years ago, but it took the laboratory 3 months to finish quantifying telomere length for just 100 samples, which was not enough to draw any meaningful conclusions,” Dr Yuan said.

“Not even a decade later, we’ve been able to run nearly 30,000 samples in a year and draw these really robust insights, showing how far technology has come. Even more complicated will be linking telomere length to genome-wide analyses, which is on the horizon. We’re on the cusp of gaining a truly remarkable understanding of the complicated biological phenomena that lead to cancer.” ![]()

*The presentation differed from the abstract.