User login

The English expression, “a pain in the neck” is said to have originated in the early 1900s as a euphemism for the less polite phrase, “a pain in the ass.”1 While one might wonder how the expressions of such disparate discomforts came to be idiomatically equivalent, the focus of this article is on etiology of the former. All wryness aside, since most ED presentations of neck pain are musculoskeletal in origin, one may easily fail to consider the myriad of less common, but possibly serious, causes.

Pain can originate from any part of the neck and occur as a result of inflammation (eg, infections and arthritides), vascular pathology (eg, cervical artery dissection [CAD]), spaceoccupying lesions (eg, hematomas, cysts, tumors), or even as referred pain from noncervical sources (eg, heart, diaphragm, lung apex). Any lesion encroaching on the limited space of the neck can quickly compromise the airway, compress nerves, or inhibit blood flow to the brain; therefore, knowledge of the causes of such conditions is critical. This article reviews some of the less common and generally atraumatic etiologies of nontraumatic neck pain of which the emergency physician should be familiar.

Vascular Disorders

Vascular-associated neck pain can originate from vessels within the neck or represent referred pain from a more distant structure. In both cases, however, the potential for morbidity is high and the need for consideration and timely recognition crucial.

Cervical Artery Dissection

The typical initial presenting symptom of CAD—ie, internal CAD (ICAD) or vertebral artery dissection (VAD)—is severe pain in the ipsilateral neck and/or head. Onset of pain may be sudden or gradual.2 CAD occurs in an estimated 2 or 3 of every 100,000 people per year, mostly in patients between ages 20 and 40 years, and it is considered the most common cause of stroke in patients younger than age 45 years.2 The pain associated with CAD generally follows trauma. While the precipitating trauma can be a major blunt or penetrating one, it is often caused by something seemingly trivial, such as “trauma” associated with coughing, painting a ceiling, yoga, or (classically and notoriously) chiropractic manipulation.3 There is frequently some rotational component to CAD-associated trauma,4 though dissection may occur spontaneously.5

The typical triad of symptoms is ipsilateral neck and/or head pain, partial Horner’s syndrome (ptosis and miosis without anhidrosis), and signs of cerebral ischemia. However, patients do not always present with all three of these symptoms, which can complicate the diagnosis. For example, in some patients, neck pain is the sole presenting symptom and can mimic the musculoskeletal pain expected from the mechanical strain that precipitated the dissection.6 In addition, partial Horner’s syndrome occurs in only 50% of cases, and ischemic symptoms might not present for hours to weeks after the onset of neck pain.6

In almost all cases of CAD, initial symptoms are otherwise unexplained pain described as a constant, steady aching. 7 Since cervical arteries are heavily invested with pain fibers,8 an intimal tear with dissecting intramural hematoma provokes pain. Pain associated with VAD is usually severe, unilateral, posterior neck, and/or occipital, while ICAD-associated pain is ipsilateral, anterolateral neck, head, and/or face. It is important to note that head or neck pain caused by a dissection normally precedes the ischemic manifestation as opposed to the more common stroke, in which the ischemia precedes or is simultaneous with the accompanying headache.9

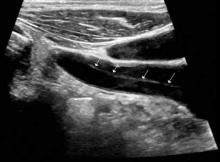

Ischemic neurological symptoms can arise from stenosis of the arterial lumen, secondary to an expanding intramural hematoma; a luminal thrombus developing at the intimal defect; or an embolization accompanied by ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, any cranial nerve abnormality, or followed by cerebral or ocular ischemic symptoms (even if transient). A diagnosis is usually made through vascular ultrasound (Figure 1) and confirmed with computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography. When requesting a CTA of the neck, the emergency physician should specifically make note of suspected CAD in the order. Immediate treatment includes a cervical collar and neurosurgical consultation even though treatment is essentially medical and surgery is rarely required. Anticoagulation therapy is routinely initiated to prevent thrombus propagation or embolization (unless there is brain hemorrhage). Antiplatelet therapy may be equally efficacious, 10 and can be initiated upon suspicions of CAD and while confirmatory studies are in progress. The prognosis for extracranial dissections is generally good.

Cervical Epidural Hematoma Cervical (spinal) epidural hematoma is an uncommon but potentially catastrophic event that can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. It presents as sudden and severe local neck pain with rapid development of radicular pain at the corresponding dermatomes. Motor and sensory deficits follow within minutes to days.12,13 Bleeding can occur spontaneously or secondary to trauma, surgery, or coagulopathy (which itself may be pathological—eg, hemophilia or iatrogenic in origin).14,15 Untreated, progressive cord compression can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. In the patient with acute neurological deficits, immediate correction of coagulation issues is required before decompressive surgery.

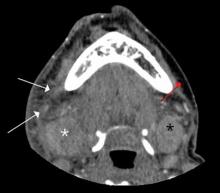

Diagnosis of cervical epidural hematoma is complicated by the rarity of the event and the lack of specific symptoms. When trauma is involved, cervical disc or nerve root injury is a more likely cause of sudden onset of neck pain, with rapid development of a radicular component. However, when symptoms occur following minor exertion (eg, sneezing, coitus, coughing) and in the presence of risk factors such as hematologic disorders, pregnancy, rheumatologic disorders, or liver dysfunction, epidural hematoma must be considered.16 Emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice for detecting this condition (Figure 2).

Coronary Ischemia Angina pectoris secondary to coronary ischemia is described as retrosternal “heaviness” or pressure, which may spread to either or both arms, the neck, or jaw. Pathology originating in the neck can be experienced as chest pain and may confound the diagnosis. Because cervical nerve roots C4-C8 contribute to the innervation of the anterior chest wall, irritation of any one of these nerves secondary to neck pathology can mimic true angina.17,18 Conversely, the likelihood that the only pain caused by coronary ischemia might be felt in the neck is low, but possible— especially in women.19,20 Coronary ischemia should be considered in patients with cardiac risk factors but no other obvious etiology for neck pain.21

Secondary Infection

Since emergency physicians are accustomed to dealing with infection, it is hard to imagine that we could fail to recognize infection as the etiology in a patient with a chief complaint of neck pain. Diagnosis in such cases is complicated by the anatomical location of deep neck-space infections, which limits the usefulness of standard physical examination. These sites are difficult to palpate and often impossible to visualize because they are covered with noninfected tissue. Unless specifically considered in the differential, more obscure causes of neck pain associated with infection may be missed, including retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, Ludwig’s angina, vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis, cervical epidural abscess, and Lemierre’s syndrome.

Epiglottitis

Epiglottitis is inflammation of the epiglottis and adjacent supraglottic structures including the pharynx, uvula, and base of the tongue. The first recorded case is thought to have been that of George Washington, who is believed to have died from this disease.22 The high mortality rate (7% to 20% in the adult population) is a direct result of airway obstruction from inflammatory edema of the epiglottis and adjacent tissues.

Epiglottitis was originally considered a childhood disease; however, the widespread use of Haemophilus influenza vaccination has resulted in a decline in pediatric incidence. Most cases are now seen in adults (mean age of 46 years).23,24

Bacterial infection, especially from the genera Hemophilus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Klebsiella, is by far the most frequent cause of acute epiglottitis; viral and fungal-associated infections are rare. Thermal injury from swallowing hot foods or liquids, and even from inhaling crack cocaine,25 also has been implicated.

Clinical presentations of epiglottitis differ between children and adults. While children are typically dyspneic, drooling, stridorous and febrile, adults tend to present with a milder form of the disease and have painful swallowing, sore throat, and a muffled voice. In both children and adults, the larynx and upper trachea are tender to light palpation at the anterior neck.26 Although sore throat and odynophagia are more often symptoms of pharyngitis, suspicion should be aroused when pain is severe and/or there is dyspnea, severe pain with an unremarkable oropharynx examination, or anterior neck tenderness. When present, muffled voice and stridor indicate greater potential for airway compromise.27 In cases of significant airway obstruction, patients may assume the “tripod position,” leaning forward with neck extended and mouth open—panting. Since soft-tissue lateral neck radiographs are about 90% sensitive and specific for epiglottitis, a normalappearing film cannot reliably exclude the diagnosis.28 Evaluation for the classic “thumb sign” of epiglottic swelling27 (Figure 3) should be combined with the newly described “vallecula sign” for greatest accuracy.29 The vallecula sign is described as the partial or complete obliteration of a well-defined linear air pocket between the base of the tongue and the epiglottis seen on a closed mouth lateral neck X-ray.

Although CT is a useful modality for detecting epiglottic, peritonsillar, or deep neck space abscess, there are risks to patients with airway compromise; moreover, placing patients in a supine position for the study increases the likelihood of respiratory distress. Despite these risks, when indicated, CT is useful in differentiating these abscesses from similarly presenting entities such as lingual tonsillitis and upper airway foreign body.

Direct visualization via flexible oral or nasolaryngoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard but may be deferred in a stable patient. When absolutely indicated, it must be performed with caution, ideally by an anesthesiologist/otolaryngologist in a controlled setting, lest it precipitate further obstruction. Through the use of fiber optics, the need for emergent intubation can be more directly assessed and, if necessary, performed by “tube-over-scope” technique. In the ED, standby equipment for intubation and cricothyrotomy/needle cricothyrotomy should be immediately available and ready in the event of rapid deterioration, at the same time as intravenous (IV) infusion of third-generation cephalosporin or ampicillin/sulbactam, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) coverage. Though the rationale for empirical use of antibiotics is evident, the role of corticosteroids and of nebulized racemic epinephrine is controversial.

Death, airway obstruction, epiglottic abscess, necrotizing epiglottitis, and secondary infections (eg, pneumonia, cervical adenitis, septic arthritis, meningitis) are the potential complications that make this source of neck pain one not to be missed. If epiglottitis is suspected, the patient must be admitted to an intensive care setting.

Retropharyngeal Abscess

The retropharyngeal space, immediately behind the posterior pharynx and esophagus, extends from the base of the skull to the mediastinum. It lies anterior to the deep cervical fascia and is bound laterally by the carotid sheaths.30 Because it is fused down the midline, abscesses in this area tend to be unilateral. The space cannot be directly assessed by physical examination, and infections in this area are rare. Timely diagnosis demands consideration of retropharyngeal abscess in patients presenting with fever, neck stiffness, and sore throat. The potential for serious morbidity and mortality is related to the host of vital structures immediately adjacent to the retropharyngeal space. Complications include mediastinitis, carotid artery erosion, jugular vein thrombosis, pericarditis, epidural abscess, sepsis, and airway compromise.

Most cases are typically observed in children younger than age 6 years. In this pediatric population, the retropharyngeal space has two parallel chains of lymph nodes draining the nose, sinuses, and pharynx; retropharyngeal abscesses usually occur as a suppurative extension from infections of these upper airway structures structures. Penetrating trauma, eg, from objects held in the mouth, is another possible cause. These nodes atrophy around 6 years of age; thereafter, the main cause of retropharyngeal abscess is purulent extension of an adjacent (frequently odontogenic) infection or posterior pharyngeal trauma (eg, from a fish bone or instrumentation).31 As befits its origin with oral flora, cultures are almost always polymicrobial (eg, Streptococci viridans and pyogenes, Staphylococcus, H influenza, Klebsiella, anaerobes).

Although retropharyngeal abscess is considered a disease of childhood, like epiglottitis, its incidence in adults is increasing. 32 Presenting symptoms are signs of respiratory distress, such as wheezing, stridor, and drooling with impending airway obstruction from the expanding posterior pharyngeal mass. Late signs of the illness are respiratory failure due to airway obstruction and septic shock, but an astute clinician should recognize the entity long before these symptoms present. Early symptoms include fever, sore throat, odynophagia, and neck pain and stiffness (typically manifesting as a reluctance to turn the neck).33 Patients may also complain of feeling a lump in the throat or pain in the posterior neck or shoulder with swallowing.34 Ninety-seven percent of pediatric patients present with neck pain,32 which could manifest dramatically as torticollis. Most likely, a child will have a subtle reluctance to move his or her neck during the course of the physical examination. In addition, there may be posterior pharyngeal edema and/or a visible unilateral posterior pharyngeal bulge, cervical adenopathy, and a “croupy” cry or cough resembling a duck’s quack—the “cri du canard.”35 Definitive diagnosis is made using X-ray and/or CT. A lateral soft-tissue neck X-ray will demonstrate widening of the prevertebral soft tissues. CT with contrast provides a more definitive diagnosis, and is also useful to differentiate abscess (ie, a hypodense lesion with ring enhancement) from cellulitis.

Regarding treatment, empiric IV antibiotics must be started immediately and may alone prevent progression if the diagnosis is made before cellulitis has progressed to abscess. Intravenous clindamycin is a reasonable first-line antibiotic; other suggested drugs include a penicillin/ beta lactamase inhibitor, penicillin G plus metronidazole, and cefoxitin.36 Airway protection is mandatory, and an otolaryngologist should be consulted early. Because of the potential for sudden airway deterioration, the emergency physician must be prepared to establish a surgical airway.

Ludwig’s Angina

Ludwig’s angina derives its name from the German physician Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig, who first described this deadly, rapidly progressive, fascial space/ connective tissue gangrenous cellulitis of the floor of the mouth and adjoining neck in 1836. In a curious twist of fate, it is believed that Dr Ludwig died from this very disease that bears his name.37

Ninety percent of cases of Ludwig’s angina are odontogenic, often due to periapical abscesses. This condition may result secondary to any oral or parapharyngeal infection that spreads by continuity from the submandibular space into the contiguous sublingual and submental spaces. The potential for airway obstruction comes from elevation and displacement of the tongue, resulting in a mortality rate greater than 50% if untreated. Causative organisms mirror normal, polymicrobial oral flora and include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Bacteroides.38,23

Diagnosis of Ludwig’s angina is primarily clinical. Neck pain and swelling, dental pain, dysphagia, malaise, and fever, along with a protruding or elevated tongue, are typical. Submandibular swelling, which is seen in 95% of patients, develops in advanced cases into an intense “woody” induration above the hyoid bone that portends the impending airway crisis.39 If the patient is sufficiently clinically stable and able to lie flat, definitive diagnosis can be made with a contrastenhanced, soft-tissue neck CT (Figure 4), which can also evaluate for a drainable abscess, soft-tissue gas, and mediastinal extension; this modality can also define the extent of soft-tissue swelling and airway patency.

Airway management is the primary consideration because of its potential for rapid deterioration. Traditional management has been aggressive and surgical, with the standard being early tracheostomy. More recent reports have encouraged more conservative management when possible.40 Impending or actual airway compromise, as manifest by significant trismus, inability to flex the neck without compromising the airway, inability to protrude the tongue, or actual resting dyspnea demand that a surgical airway be readied at bedside until fiber optic nasotracheal intubation is secured.

Antibiotics must be given early and include coverage for gram-positive, gramnegative, and anaerobic organisms. Intravenous metronidazole and penicillin (cefazolin or clindamycin if patient has an allergy to penicillin) are commonly prescribed.38,23 Although controversial, administration of IV dexamethasone (8 mg to 12 mg) and nebulized epinephrine (1:1000, 1 mL diluted to 5 mL with normal saline) to reduce edema has been advocated. 41

Lemierre’s Syndrome Lemierre’s syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, was first described in 1936 by André Lemierre, who published a series of cases of previously healthy young adults in whom oropharyngeal infections were followed by “anaerobic postanginal septicaemias.”42 Most of these patients presented with sore throat (referred to as “angina” in “old skool” speak) and worsening pain and tenderness at the anterolateral neck, with pulmonary symptoms manifesting several days to 2 weeks later. The causative organism, Fusobacterium necrophorum, is a gram-negative anaerobe that is part of the normal commensal oropharyngeal flora. It invades the internal jugular (IJ) vein via the lateral pharyngeal space and releases a hemagglutinin that promotes thrombus formation in the IJ and, ultimately, metastatic septic emboli. These emboli typically invade the lungs and cause multiple nodular infiltrates and small pleural effusions. Unfortunately, as each case is unique, diagnosis is often delayed. Septic emboli can migrate to other sites and cause arthritis (hip, knee, shoulder, sacroiliac, and other joints), osteomyelitis, young adult with a history of recent sore throat and fever who subsequently developed neck pain and tenderness (with or without swelling) over the IJ, rigors, pulmonary infiltrates, and possibly other signs of septic emboli.

Doppler ultrasound or CT will show IJ thrombosis43 (Figure 5). Purulent discharge, if obtained, has a characteristic foul smell that has been likened to “limburger or overripe Camembert cheese.”44 Treatment is with high-dose IV penicillin and metronidazole or with clindamycin as single coverage. Heparin could potentially aid in dissemination of emboli, but it is used only when there is retrograde propagation of clot to the cavernous sinus.

With the routine antibiotic treatment of pharyngitis in the 1960s and 1970s, cases of Lemierre’s syndrome became so rare that it was referred to as the “forgotten disease.”45 Unfortunately, its incidence has increased over the past few years.43 It is unclear whether this rise is due to increasing antibiotic resistance or to an increasing resistance of clinicians to use antibiotics for “sore throats.”

Cervical Spinal Infections

Vertebral osteomyelitis, discitis, and spinal epidural abscess are rare in developed countries. Most cases stem from hematogenous seeding, skin abscesses, and urinary tract infections but can also originate from a host of other sites, including penetrating trauma and invasive spinal procedures (eg, lumbar punctures, epidural injections). 46,47 Cervical spine infections are associated with immune-compromising situations or conditions (eg, IV drug use, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, renal insufficiency, long-term use of systemic corticosteroids).

All three of these conditions present similarly, often as localized neck pain that grows more intense over a period of days to weeks and worsens with neck movement. Neurological signs ordinarily appear late in the course of the illness. Fever is a classic symptom but is not always present.48 There is usually tenderness over the involved spinous process. The development of motor or sensory loss suggests formation of an abscess,49 which can rapidly lead to further compressive symptoms and sepsis.

Leukocytosis may be absent but erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are often elevated. A CT scan with contrast is frequently required for diagnosis, though when available, MRI with IV gadolinium is the test of choice (Figure 6). Most cases are caused by S aureus, but antibiotic coverage for gram-positive organisms (including MRSA), gram-negative organisms, and anaerobes should be started as soon as blood cultures are drawn. Neurosurgery should be consulted emergently since, with cervical epidural abscess, neurological deterioration—even to the point of total paralysis—can develop in a matter of hours.50

Conclusion

Although most patients presenting to the ED with neck pain are musculoskeletal and associated with a traumatic event, other infrequent but potentially serious atraumatic causes may be present. Based on a patient’s symptoms, emergency physicians should also consider these conditions in the differential diagnosis to ensure rapid treatment to prevent further complications.

- Ammer C. The American heritage dictionary of idioms. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1997:489.

- Fusco MR, Harrigan MR. Cerebrovascular dissections—a review part I: spontaneous dissections. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(1):242-257.

- Rubinstein SM, Peerdeman SM, van Tulder MW, Riphagen I, Haldeman S. A systematic review of the risk factors for cervical artery dissection. Stroke.2005;36(7):1575-1580.

- Bergin M, Bird P, Wright A. Internal carotid artery dissection following canalith repositioning procedure. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124(5):575, 576.

- Brandt T, Grond-Ginsbach C. Spontaneous cervical artery dissection: from risk factors toward pathogenesis. Stroke. 2002;33(3):657,658.

- Arnold M, Cumurciuc R, Stapf C, Favrole P, Berthet K, Bousser MG. Pain as the only symptom of cervical artery dissection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(9):1021-1024.

- Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):898-906.

- Caplan LR. Dissections of brain-supplying arteries. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(1):34-42.

- Silbert PL, Mokri B, Schievink WI. Headache and neck pain in spontaneous internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1517-1522.

- Engelter ST, Brandt T, Debette S; Cervical Artery Dissection in Ischemic Stroke Patients (CADISP) Study Group. Antiplatelets versus anticoagulation in cervical artery dissection. Stroke. 2007;38(9):2605-2611.

- Arnold M, Bousser M, Fahrni G, et al. Vertebral artery dissection: presenting findings and predictors of outcome. Stroke. 2006;37(10):2499-2503.

- Hsieh CT, Chang CF, Lin EY, Tsai TH, Chiang YH, Ju DT. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas of cervical spine: report of 4 cases and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(6):736-740.

- Sei A, Nakamura T, Hashimoto N, Mizuta H, Sasaki A, Takagi K. Cervical spinal epidural hematoma with spontaneous remission. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4(2):234-237.

- Williams JM, Allegra JR. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(6):1368-1370.

- Demierre B, Unger PF, Bongioanni F. Sudden cervical pain: spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9(1):54-56.

- Broder J, L’Italien A. Evaluation and management of the patient with neck pain. In: Mattu A, Goyal DG eds. Emergency Medicine: Avoiding the Pitfalls and Improving the Outcomes. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, Inc; 2007:46-54. http://onlinelibrary. wiley.com/book/10.1002/9780470755938. Accessed November 15, 2013.

- Brodsky AE. Cervical angina. A correlative study with emphasis on the use of coronary arteriography. Spine. 1985;10(8):699-709.

- Hanflig SS. Pain in the shoulder girdle, arm and precordium due to cervical arthritis. JAMA. 1936;106(7):523-526.

- Goldberg R, Goff D, Cooper L, et al. Age and sex differences in presentation of symptoms among patients with acute coronary disease: the REACT Trial. Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment. Coron Artery Dis. 2000;11(5):399-407.

- Coventry LL, Finn J, Bremner AP. Sex differences in symptom presentation in acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 2011;40(6):477-491.

- Lipetz JS, Ledon J, Silber J. Severe coronary artery disease presenting with a chief complaint of cervical pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(9):716-720.

- Morens DM. Death of a president. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(24):1845-1849.

- Winters M. Evidence-based diagnosis and management of ENT emergencies. Medscape. 2007. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/551650_1. Accessed November 15, 2013.

- Mayo-Smith MF, Spinale JW, Donskey CJ, Yukawa M, Li RH, Schiffman FJ. Acute epiglottitis: An 18-year experience in Rhode Island. Chest. 1995;108(6):1640-1670.

- Mayo-Smith MF, Spinale J. Thermal epiglottitis in adults: a new complication of illicit drug use. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(4):483-485.

- Bansal A, Miskoff J, Lis RJ. Otolaryngologic critical care. Crit Care Clin. 2003;19(1):55-72.

- Katori H, Tsukuda M. Acute epiglottitis: analysis of factors associated with airway intervention. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119(12):967-972.

- Rothrock SG, Pignatiello GA, Howard RM. Radiologic diagnosis of epiglottitis: objective criteria for all ages. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(9):978-982.

- Ducic Y, Hébert PC, MacLachlan L, Neufeld K, Lamothe A. Description and evaluation of the vallecula sign: a new radiologic sign in the diagnosis of adult epiglottitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(1):1-6.

- Vieira F, Allen SM, Stocks RM, Thompson JW. Deep neck infection. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(3):459-483.

- Shores CG. Infections and disorders of the neck and upper airway. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Kelen GD, eds. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004:1494-1499.

- Kahn JH. Retropharyngeal Abscess in Emergency Medicine. Medscape Review. 2008.

- Gibson CG. Do not rely on the presence of respiratory compromise to make the diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess. In: Mattu A, Chanmugam AS, Swadron SP, Tibbles CD, Woolridge DP, eds. Avoiding Common Errors in the Emergency Department. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:212.

- Greene JS, Asher IM. Retropharyngeal abscess: A previously unreported symptom. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13(8):615-619.

- Melio FR. Upper respiratory tract infections. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine-Concepts and Clinical Practice 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2009:921-923.

- Sanford JP, Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, Sande MA, Eliopoulos GM, eds. The Sanford guide to Antimicrobial Therapy 2006-2007. 37th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc; 2007:30.

- Murphy SC. The person behind the eponym: Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig (1790-1865). J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25(9):513-515.

- Hasan W, Leonard D, Russell J. Ludwig’s Angina—A controversial surgical emergency: How we do it. Int J Otolaryngol. 2011;2011:231816.

- Saifeldeen K, Evans R. Ludwig’s angina. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(2):242,243.

- Marple BF. Ludwig angina: a review of current airway management. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(5):596-599.

- Buckley MF, O’Connor K. Ludwig’s angina in a 76-year-old man. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(9):679-680.

- Lemierre A. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;227(5874):701-703.

- Karkos PD, Asrani S, Karkos CD, et al. Lemierre’s syndrome: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(8):1552-1559.

- Alston JM. Necrobacillosis in Great Britain. Brit Med J. 1955;2(4955):1524-1528.

- Vargiami EG, Zafeiriou D. Eponym: The Lemierre syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(4):411-414.

- Martínez Hernández PL, Amer López M, Zamora Vargas F, et al. Spontaneous infectious spondylodiscitis in an internal medicine department: epidemiological and clinical study in 41 cases. Rev Clin Esp. 2008;208(7):347-352.

- Urrutia J, Bono CM, Mery P, Rojas C, Gana N, Campos M. Chronic liver failure and concomitant distant infections are associated with high rates of neurological involvement in pyogenic spinal infections. Spine. 2009;34(7):E240-E244.

- Buranapanitkit B, Lim A, Kiriratnikom T. Clinical manifestation of tuberculous and pyogenic spine infection. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84(11):1522-1526.

- Schimmer RC, Jeanneret C, Nunley PD, Jeanneret B. Osteomyelitis of the cervical spine: a potentially dramatic disease. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15(2):110-117.

- Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):2012-2020.

The English expression, “a pain in the neck” is said to have originated in the early 1900s as a euphemism for the less polite phrase, “a pain in the ass.”1 While one might wonder how the expressions of such disparate discomforts came to be idiomatically equivalent, the focus of this article is on etiology of the former. All wryness aside, since most ED presentations of neck pain are musculoskeletal in origin, one may easily fail to consider the myriad of less common, but possibly serious, causes.

Pain can originate from any part of the neck and occur as a result of inflammation (eg, infections and arthritides), vascular pathology (eg, cervical artery dissection [CAD]), spaceoccupying lesions (eg, hematomas, cysts, tumors), or even as referred pain from noncervical sources (eg, heart, diaphragm, lung apex). Any lesion encroaching on the limited space of the neck can quickly compromise the airway, compress nerves, or inhibit blood flow to the brain; therefore, knowledge of the causes of such conditions is critical. This article reviews some of the less common and generally atraumatic etiologies of nontraumatic neck pain of which the emergency physician should be familiar.

Vascular Disorders

Vascular-associated neck pain can originate from vessels within the neck or represent referred pain from a more distant structure. In both cases, however, the potential for morbidity is high and the need for consideration and timely recognition crucial.

Cervical Artery Dissection

The typical initial presenting symptom of CAD—ie, internal CAD (ICAD) or vertebral artery dissection (VAD)—is severe pain in the ipsilateral neck and/or head. Onset of pain may be sudden or gradual.2 CAD occurs in an estimated 2 or 3 of every 100,000 people per year, mostly in patients between ages 20 and 40 years, and it is considered the most common cause of stroke in patients younger than age 45 years.2 The pain associated with CAD generally follows trauma. While the precipitating trauma can be a major blunt or penetrating one, it is often caused by something seemingly trivial, such as “trauma” associated with coughing, painting a ceiling, yoga, or (classically and notoriously) chiropractic manipulation.3 There is frequently some rotational component to CAD-associated trauma,4 though dissection may occur spontaneously.5

The typical triad of symptoms is ipsilateral neck and/or head pain, partial Horner’s syndrome (ptosis and miosis without anhidrosis), and signs of cerebral ischemia. However, patients do not always present with all three of these symptoms, which can complicate the diagnosis. For example, in some patients, neck pain is the sole presenting symptom and can mimic the musculoskeletal pain expected from the mechanical strain that precipitated the dissection.6 In addition, partial Horner’s syndrome occurs in only 50% of cases, and ischemic symptoms might not present for hours to weeks after the onset of neck pain.6

In almost all cases of CAD, initial symptoms are otherwise unexplained pain described as a constant, steady aching. 7 Since cervical arteries are heavily invested with pain fibers,8 an intimal tear with dissecting intramural hematoma provokes pain. Pain associated with VAD is usually severe, unilateral, posterior neck, and/or occipital, while ICAD-associated pain is ipsilateral, anterolateral neck, head, and/or face. It is important to note that head or neck pain caused by a dissection normally precedes the ischemic manifestation as opposed to the more common stroke, in which the ischemia precedes or is simultaneous with the accompanying headache.9

Ischemic neurological symptoms can arise from stenosis of the arterial lumen, secondary to an expanding intramural hematoma; a luminal thrombus developing at the intimal defect; or an embolization accompanied by ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, any cranial nerve abnormality, or followed by cerebral or ocular ischemic symptoms (even if transient). A diagnosis is usually made through vascular ultrasound (Figure 1) and confirmed with computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography. When requesting a CTA of the neck, the emergency physician should specifically make note of suspected CAD in the order. Immediate treatment includes a cervical collar and neurosurgical consultation even though treatment is essentially medical and surgery is rarely required. Anticoagulation therapy is routinely initiated to prevent thrombus propagation or embolization (unless there is brain hemorrhage). Antiplatelet therapy may be equally efficacious, 10 and can be initiated upon suspicions of CAD and while confirmatory studies are in progress. The prognosis for extracranial dissections is generally good.

Cervical Epidural Hematoma Cervical (spinal) epidural hematoma is an uncommon but potentially catastrophic event that can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. It presents as sudden and severe local neck pain with rapid development of radicular pain at the corresponding dermatomes. Motor and sensory deficits follow within minutes to days.12,13 Bleeding can occur spontaneously or secondary to trauma, surgery, or coagulopathy (which itself may be pathological—eg, hemophilia or iatrogenic in origin).14,15 Untreated, progressive cord compression can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. In the patient with acute neurological deficits, immediate correction of coagulation issues is required before decompressive surgery.

Diagnosis of cervical epidural hematoma is complicated by the rarity of the event and the lack of specific symptoms. When trauma is involved, cervical disc or nerve root injury is a more likely cause of sudden onset of neck pain, with rapid development of a radicular component. However, when symptoms occur following minor exertion (eg, sneezing, coitus, coughing) and in the presence of risk factors such as hematologic disorders, pregnancy, rheumatologic disorders, or liver dysfunction, epidural hematoma must be considered.16 Emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice for detecting this condition (Figure 2).

Coronary Ischemia Angina pectoris secondary to coronary ischemia is described as retrosternal “heaviness” or pressure, which may spread to either or both arms, the neck, or jaw. Pathology originating in the neck can be experienced as chest pain and may confound the diagnosis. Because cervical nerve roots C4-C8 contribute to the innervation of the anterior chest wall, irritation of any one of these nerves secondary to neck pathology can mimic true angina.17,18 Conversely, the likelihood that the only pain caused by coronary ischemia might be felt in the neck is low, but possible— especially in women.19,20 Coronary ischemia should be considered in patients with cardiac risk factors but no other obvious etiology for neck pain.21

Secondary Infection

Since emergency physicians are accustomed to dealing with infection, it is hard to imagine that we could fail to recognize infection as the etiology in a patient with a chief complaint of neck pain. Diagnosis in such cases is complicated by the anatomical location of deep neck-space infections, which limits the usefulness of standard physical examination. These sites are difficult to palpate and often impossible to visualize because they are covered with noninfected tissue. Unless specifically considered in the differential, more obscure causes of neck pain associated with infection may be missed, including retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, Ludwig’s angina, vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis, cervical epidural abscess, and Lemierre’s syndrome.

Epiglottitis

Epiglottitis is inflammation of the epiglottis and adjacent supraglottic structures including the pharynx, uvula, and base of the tongue. The first recorded case is thought to have been that of George Washington, who is believed to have died from this disease.22 The high mortality rate (7% to 20% in the adult population) is a direct result of airway obstruction from inflammatory edema of the epiglottis and adjacent tissues.

Epiglottitis was originally considered a childhood disease; however, the widespread use of Haemophilus influenza vaccination has resulted in a decline in pediatric incidence. Most cases are now seen in adults (mean age of 46 years).23,24

Bacterial infection, especially from the genera Hemophilus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Klebsiella, is by far the most frequent cause of acute epiglottitis; viral and fungal-associated infections are rare. Thermal injury from swallowing hot foods or liquids, and even from inhaling crack cocaine,25 also has been implicated.

Clinical presentations of epiglottitis differ between children and adults. While children are typically dyspneic, drooling, stridorous and febrile, adults tend to present with a milder form of the disease and have painful swallowing, sore throat, and a muffled voice. In both children and adults, the larynx and upper trachea are tender to light palpation at the anterior neck.26 Although sore throat and odynophagia are more often symptoms of pharyngitis, suspicion should be aroused when pain is severe and/or there is dyspnea, severe pain with an unremarkable oropharynx examination, or anterior neck tenderness. When present, muffled voice and stridor indicate greater potential for airway compromise.27 In cases of significant airway obstruction, patients may assume the “tripod position,” leaning forward with neck extended and mouth open—panting. Since soft-tissue lateral neck radiographs are about 90% sensitive and specific for epiglottitis, a normalappearing film cannot reliably exclude the diagnosis.28 Evaluation for the classic “thumb sign” of epiglottic swelling27 (Figure 3) should be combined with the newly described “vallecula sign” for greatest accuracy.29 The vallecula sign is described as the partial or complete obliteration of a well-defined linear air pocket between the base of the tongue and the epiglottis seen on a closed mouth lateral neck X-ray.

Although CT is a useful modality for detecting epiglottic, peritonsillar, or deep neck space abscess, there are risks to patients with airway compromise; moreover, placing patients in a supine position for the study increases the likelihood of respiratory distress. Despite these risks, when indicated, CT is useful in differentiating these abscesses from similarly presenting entities such as lingual tonsillitis and upper airway foreign body.

Direct visualization via flexible oral or nasolaryngoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard but may be deferred in a stable patient. When absolutely indicated, it must be performed with caution, ideally by an anesthesiologist/otolaryngologist in a controlled setting, lest it precipitate further obstruction. Through the use of fiber optics, the need for emergent intubation can be more directly assessed and, if necessary, performed by “tube-over-scope” technique. In the ED, standby equipment for intubation and cricothyrotomy/needle cricothyrotomy should be immediately available and ready in the event of rapid deterioration, at the same time as intravenous (IV) infusion of third-generation cephalosporin or ampicillin/sulbactam, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) coverage. Though the rationale for empirical use of antibiotics is evident, the role of corticosteroids and of nebulized racemic epinephrine is controversial.

Death, airway obstruction, epiglottic abscess, necrotizing epiglottitis, and secondary infections (eg, pneumonia, cervical adenitis, septic arthritis, meningitis) are the potential complications that make this source of neck pain one not to be missed. If epiglottitis is suspected, the patient must be admitted to an intensive care setting.

Retropharyngeal Abscess

The retropharyngeal space, immediately behind the posterior pharynx and esophagus, extends from the base of the skull to the mediastinum. It lies anterior to the deep cervical fascia and is bound laterally by the carotid sheaths.30 Because it is fused down the midline, abscesses in this area tend to be unilateral. The space cannot be directly assessed by physical examination, and infections in this area are rare. Timely diagnosis demands consideration of retropharyngeal abscess in patients presenting with fever, neck stiffness, and sore throat. The potential for serious morbidity and mortality is related to the host of vital structures immediately adjacent to the retropharyngeal space. Complications include mediastinitis, carotid artery erosion, jugular vein thrombosis, pericarditis, epidural abscess, sepsis, and airway compromise.

Most cases are typically observed in children younger than age 6 years. In this pediatric population, the retropharyngeal space has two parallel chains of lymph nodes draining the nose, sinuses, and pharynx; retropharyngeal abscesses usually occur as a suppurative extension from infections of these upper airway structures structures. Penetrating trauma, eg, from objects held in the mouth, is another possible cause. These nodes atrophy around 6 years of age; thereafter, the main cause of retropharyngeal abscess is purulent extension of an adjacent (frequently odontogenic) infection or posterior pharyngeal trauma (eg, from a fish bone or instrumentation).31 As befits its origin with oral flora, cultures are almost always polymicrobial (eg, Streptococci viridans and pyogenes, Staphylococcus, H influenza, Klebsiella, anaerobes).

Although retropharyngeal abscess is considered a disease of childhood, like epiglottitis, its incidence in adults is increasing. 32 Presenting symptoms are signs of respiratory distress, such as wheezing, stridor, and drooling with impending airway obstruction from the expanding posterior pharyngeal mass. Late signs of the illness are respiratory failure due to airway obstruction and septic shock, but an astute clinician should recognize the entity long before these symptoms present. Early symptoms include fever, sore throat, odynophagia, and neck pain and stiffness (typically manifesting as a reluctance to turn the neck).33 Patients may also complain of feeling a lump in the throat or pain in the posterior neck or shoulder with swallowing.34 Ninety-seven percent of pediatric patients present with neck pain,32 which could manifest dramatically as torticollis. Most likely, a child will have a subtle reluctance to move his or her neck during the course of the physical examination. In addition, there may be posterior pharyngeal edema and/or a visible unilateral posterior pharyngeal bulge, cervical adenopathy, and a “croupy” cry or cough resembling a duck’s quack—the “cri du canard.”35 Definitive diagnosis is made using X-ray and/or CT. A lateral soft-tissue neck X-ray will demonstrate widening of the prevertebral soft tissues. CT with contrast provides a more definitive diagnosis, and is also useful to differentiate abscess (ie, a hypodense lesion with ring enhancement) from cellulitis.

Regarding treatment, empiric IV antibiotics must be started immediately and may alone prevent progression if the diagnosis is made before cellulitis has progressed to abscess. Intravenous clindamycin is a reasonable first-line antibiotic; other suggested drugs include a penicillin/ beta lactamase inhibitor, penicillin G plus metronidazole, and cefoxitin.36 Airway protection is mandatory, and an otolaryngologist should be consulted early. Because of the potential for sudden airway deterioration, the emergency physician must be prepared to establish a surgical airway.

Ludwig’s Angina

Ludwig’s angina derives its name from the German physician Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig, who first described this deadly, rapidly progressive, fascial space/ connective tissue gangrenous cellulitis of the floor of the mouth and adjoining neck in 1836. In a curious twist of fate, it is believed that Dr Ludwig died from this very disease that bears his name.37

Ninety percent of cases of Ludwig’s angina are odontogenic, often due to periapical abscesses. This condition may result secondary to any oral or parapharyngeal infection that spreads by continuity from the submandibular space into the contiguous sublingual and submental spaces. The potential for airway obstruction comes from elevation and displacement of the tongue, resulting in a mortality rate greater than 50% if untreated. Causative organisms mirror normal, polymicrobial oral flora and include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Bacteroides.38,23

Diagnosis of Ludwig’s angina is primarily clinical. Neck pain and swelling, dental pain, dysphagia, malaise, and fever, along with a protruding or elevated tongue, are typical. Submandibular swelling, which is seen in 95% of patients, develops in advanced cases into an intense “woody” induration above the hyoid bone that portends the impending airway crisis.39 If the patient is sufficiently clinically stable and able to lie flat, definitive diagnosis can be made with a contrastenhanced, soft-tissue neck CT (Figure 4), which can also evaluate for a drainable abscess, soft-tissue gas, and mediastinal extension; this modality can also define the extent of soft-tissue swelling and airway patency.

Airway management is the primary consideration because of its potential for rapid deterioration. Traditional management has been aggressive and surgical, with the standard being early tracheostomy. More recent reports have encouraged more conservative management when possible.40 Impending or actual airway compromise, as manifest by significant trismus, inability to flex the neck without compromising the airway, inability to protrude the tongue, or actual resting dyspnea demand that a surgical airway be readied at bedside until fiber optic nasotracheal intubation is secured.

Antibiotics must be given early and include coverage for gram-positive, gramnegative, and anaerobic organisms. Intravenous metronidazole and penicillin (cefazolin or clindamycin if patient has an allergy to penicillin) are commonly prescribed.38,23 Although controversial, administration of IV dexamethasone (8 mg to 12 mg) and nebulized epinephrine (1:1000, 1 mL diluted to 5 mL with normal saline) to reduce edema has been advocated. 41

Lemierre’s Syndrome Lemierre’s syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, was first described in 1936 by André Lemierre, who published a series of cases of previously healthy young adults in whom oropharyngeal infections were followed by “anaerobic postanginal septicaemias.”42 Most of these patients presented with sore throat (referred to as “angina” in “old skool” speak) and worsening pain and tenderness at the anterolateral neck, with pulmonary symptoms manifesting several days to 2 weeks later. The causative organism, Fusobacterium necrophorum, is a gram-negative anaerobe that is part of the normal commensal oropharyngeal flora. It invades the internal jugular (IJ) vein via the lateral pharyngeal space and releases a hemagglutinin that promotes thrombus formation in the IJ and, ultimately, metastatic septic emboli. These emboli typically invade the lungs and cause multiple nodular infiltrates and small pleural effusions. Unfortunately, as each case is unique, diagnosis is often delayed. Septic emboli can migrate to other sites and cause arthritis (hip, knee, shoulder, sacroiliac, and other joints), osteomyelitis, young adult with a history of recent sore throat and fever who subsequently developed neck pain and tenderness (with or without swelling) over the IJ, rigors, pulmonary infiltrates, and possibly other signs of septic emboli.

Doppler ultrasound or CT will show IJ thrombosis43 (Figure 5). Purulent discharge, if obtained, has a characteristic foul smell that has been likened to “limburger or overripe Camembert cheese.”44 Treatment is with high-dose IV penicillin and metronidazole or with clindamycin as single coverage. Heparin could potentially aid in dissemination of emboli, but it is used only when there is retrograde propagation of clot to the cavernous sinus.

With the routine antibiotic treatment of pharyngitis in the 1960s and 1970s, cases of Lemierre’s syndrome became so rare that it was referred to as the “forgotten disease.”45 Unfortunately, its incidence has increased over the past few years.43 It is unclear whether this rise is due to increasing antibiotic resistance or to an increasing resistance of clinicians to use antibiotics for “sore throats.”

Cervical Spinal Infections

Vertebral osteomyelitis, discitis, and spinal epidural abscess are rare in developed countries. Most cases stem from hematogenous seeding, skin abscesses, and urinary tract infections but can also originate from a host of other sites, including penetrating trauma and invasive spinal procedures (eg, lumbar punctures, epidural injections). 46,47 Cervical spine infections are associated with immune-compromising situations or conditions (eg, IV drug use, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, renal insufficiency, long-term use of systemic corticosteroids).

All three of these conditions present similarly, often as localized neck pain that grows more intense over a period of days to weeks and worsens with neck movement. Neurological signs ordinarily appear late in the course of the illness. Fever is a classic symptom but is not always present.48 There is usually tenderness over the involved spinous process. The development of motor or sensory loss suggests formation of an abscess,49 which can rapidly lead to further compressive symptoms and sepsis.

Leukocytosis may be absent but erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are often elevated. A CT scan with contrast is frequently required for diagnosis, though when available, MRI with IV gadolinium is the test of choice (Figure 6). Most cases are caused by S aureus, but antibiotic coverage for gram-positive organisms (including MRSA), gram-negative organisms, and anaerobes should be started as soon as blood cultures are drawn. Neurosurgery should be consulted emergently since, with cervical epidural abscess, neurological deterioration—even to the point of total paralysis—can develop in a matter of hours.50

Conclusion

Although most patients presenting to the ED with neck pain are musculoskeletal and associated with a traumatic event, other infrequent but potentially serious atraumatic causes may be present. Based on a patient’s symptoms, emergency physicians should also consider these conditions in the differential diagnosis to ensure rapid treatment to prevent further complications.

The English expression, “a pain in the neck” is said to have originated in the early 1900s as a euphemism for the less polite phrase, “a pain in the ass.”1 While one might wonder how the expressions of such disparate discomforts came to be idiomatically equivalent, the focus of this article is on etiology of the former. All wryness aside, since most ED presentations of neck pain are musculoskeletal in origin, one may easily fail to consider the myriad of less common, but possibly serious, causes.

Pain can originate from any part of the neck and occur as a result of inflammation (eg, infections and arthritides), vascular pathology (eg, cervical artery dissection [CAD]), spaceoccupying lesions (eg, hematomas, cysts, tumors), or even as referred pain from noncervical sources (eg, heart, diaphragm, lung apex). Any lesion encroaching on the limited space of the neck can quickly compromise the airway, compress nerves, or inhibit blood flow to the brain; therefore, knowledge of the causes of such conditions is critical. This article reviews some of the less common and generally atraumatic etiologies of nontraumatic neck pain of which the emergency physician should be familiar.

Vascular Disorders

Vascular-associated neck pain can originate from vessels within the neck or represent referred pain from a more distant structure. In both cases, however, the potential for morbidity is high and the need for consideration and timely recognition crucial.

Cervical Artery Dissection

The typical initial presenting symptom of CAD—ie, internal CAD (ICAD) or vertebral artery dissection (VAD)—is severe pain in the ipsilateral neck and/or head. Onset of pain may be sudden or gradual.2 CAD occurs in an estimated 2 or 3 of every 100,000 people per year, mostly in patients between ages 20 and 40 years, and it is considered the most common cause of stroke in patients younger than age 45 years.2 The pain associated with CAD generally follows trauma. While the precipitating trauma can be a major blunt or penetrating one, it is often caused by something seemingly trivial, such as “trauma” associated with coughing, painting a ceiling, yoga, or (classically and notoriously) chiropractic manipulation.3 There is frequently some rotational component to CAD-associated trauma,4 though dissection may occur spontaneously.5

The typical triad of symptoms is ipsilateral neck and/or head pain, partial Horner’s syndrome (ptosis and miosis without anhidrosis), and signs of cerebral ischemia. However, patients do not always present with all three of these symptoms, which can complicate the diagnosis. For example, in some patients, neck pain is the sole presenting symptom and can mimic the musculoskeletal pain expected from the mechanical strain that precipitated the dissection.6 In addition, partial Horner’s syndrome occurs in only 50% of cases, and ischemic symptoms might not present for hours to weeks after the onset of neck pain.6

In almost all cases of CAD, initial symptoms are otherwise unexplained pain described as a constant, steady aching. 7 Since cervical arteries are heavily invested with pain fibers,8 an intimal tear with dissecting intramural hematoma provokes pain. Pain associated with VAD is usually severe, unilateral, posterior neck, and/or occipital, while ICAD-associated pain is ipsilateral, anterolateral neck, head, and/or face. It is important to note that head or neck pain caused by a dissection normally precedes the ischemic manifestation as opposed to the more common stroke, in which the ischemia precedes or is simultaneous with the accompanying headache.9

Ischemic neurological symptoms can arise from stenosis of the arterial lumen, secondary to an expanding intramural hematoma; a luminal thrombus developing at the intimal defect; or an embolization accompanied by ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, any cranial nerve abnormality, or followed by cerebral or ocular ischemic symptoms (even if transient). A diagnosis is usually made through vascular ultrasound (Figure 1) and confirmed with computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography. When requesting a CTA of the neck, the emergency physician should specifically make note of suspected CAD in the order. Immediate treatment includes a cervical collar and neurosurgical consultation even though treatment is essentially medical and surgery is rarely required. Anticoagulation therapy is routinely initiated to prevent thrombus propagation or embolization (unless there is brain hemorrhage). Antiplatelet therapy may be equally efficacious, 10 and can be initiated upon suspicions of CAD and while confirmatory studies are in progress. The prognosis for extracranial dissections is generally good.

Cervical Epidural Hematoma Cervical (spinal) epidural hematoma is an uncommon but potentially catastrophic event that can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. It presents as sudden and severe local neck pain with rapid development of radicular pain at the corresponding dermatomes. Motor and sensory deficits follow within minutes to days.12,13 Bleeding can occur spontaneously or secondary to trauma, surgery, or coagulopathy (which itself may be pathological—eg, hemophilia or iatrogenic in origin).14,15 Untreated, progressive cord compression can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. In the patient with acute neurological deficits, immediate correction of coagulation issues is required before decompressive surgery.

Diagnosis of cervical epidural hematoma is complicated by the rarity of the event and the lack of specific symptoms. When trauma is involved, cervical disc or nerve root injury is a more likely cause of sudden onset of neck pain, with rapid development of a radicular component. However, when symptoms occur following minor exertion (eg, sneezing, coitus, coughing) and in the presence of risk factors such as hematologic disorders, pregnancy, rheumatologic disorders, or liver dysfunction, epidural hematoma must be considered.16 Emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice for detecting this condition (Figure 2).

Coronary Ischemia Angina pectoris secondary to coronary ischemia is described as retrosternal “heaviness” or pressure, which may spread to either or both arms, the neck, or jaw. Pathology originating in the neck can be experienced as chest pain and may confound the diagnosis. Because cervical nerve roots C4-C8 contribute to the innervation of the anterior chest wall, irritation of any one of these nerves secondary to neck pathology can mimic true angina.17,18 Conversely, the likelihood that the only pain caused by coronary ischemia might be felt in the neck is low, but possible— especially in women.19,20 Coronary ischemia should be considered in patients with cardiac risk factors but no other obvious etiology for neck pain.21

Secondary Infection

Since emergency physicians are accustomed to dealing with infection, it is hard to imagine that we could fail to recognize infection as the etiology in a patient with a chief complaint of neck pain. Diagnosis in such cases is complicated by the anatomical location of deep neck-space infections, which limits the usefulness of standard physical examination. These sites are difficult to palpate and often impossible to visualize because they are covered with noninfected tissue. Unless specifically considered in the differential, more obscure causes of neck pain associated with infection may be missed, including retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, Ludwig’s angina, vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis, cervical epidural abscess, and Lemierre’s syndrome.

Epiglottitis

Epiglottitis is inflammation of the epiglottis and adjacent supraglottic structures including the pharynx, uvula, and base of the tongue. The first recorded case is thought to have been that of George Washington, who is believed to have died from this disease.22 The high mortality rate (7% to 20% in the adult population) is a direct result of airway obstruction from inflammatory edema of the epiglottis and adjacent tissues.

Epiglottitis was originally considered a childhood disease; however, the widespread use of Haemophilus influenza vaccination has resulted in a decline in pediatric incidence. Most cases are now seen in adults (mean age of 46 years).23,24

Bacterial infection, especially from the genera Hemophilus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Klebsiella, is by far the most frequent cause of acute epiglottitis; viral and fungal-associated infections are rare. Thermal injury from swallowing hot foods or liquids, and even from inhaling crack cocaine,25 also has been implicated.

Clinical presentations of epiglottitis differ between children and adults. While children are typically dyspneic, drooling, stridorous and febrile, adults tend to present with a milder form of the disease and have painful swallowing, sore throat, and a muffled voice. In both children and adults, the larynx and upper trachea are tender to light palpation at the anterior neck.26 Although sore throat and odynophagia are more often symptoms of pharyngitis, suspicion should be aroused when pain is severe and/or there is dyspnea, severe pain with an unremarkable oropharynx examination, or anterior neck tenderness. When present, muffled voice and stridor indicate greater potential for airway compromise.27 In cases of significant airway obstruction, patients may assume the “tripod position,” leaning forward with neck extended and mouth open—panting. Since soft-tissue lateral neck radiographs are about 90% sensitive and specific for epiglottitis, a normalappearing film cannot reliably exclude the diagnosis.28 Evaluation for the classic “thumb sign” of epiglottic swelling27 (Figure 3) should be combined with the newly described “vallecula sign” for greatest accuracy.29 The vallecula sign is described as the partial or complete obliteration of a well-defined linear air pocket between the base of the tongue and the epiglottis seen on a closed mouth lateral neck X-ray.

Although CT is a useful modality for detecting epiglottic, peritonsillar, or deep neck space abscess, there are risks to patients with airway compromise; moreover, placing patients in a supine position for the study increases the likelihood of respiratory distress. Despite these risks, when indicated, CT is useful in differentiating these abscesses from similarly presenting entities such as lingual tonsillitis and upper airway foreign body.

Direct visualization via flexible oral or nasolaryngoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard but may be deferred in a stable patient. When absolutely indicated, it must be performed with caution, ideally by an anesthesiologist/otolaryngologist in a controlled setting, lest it precipitate further obstruction. Through the use of fiber optics, the need for emergent intubation can be more directly assessed and, if necessary, performed by “tube-over-scope” technique. In the ED, standby equipment for intubation and cricothyrotomy/needle cricothyrotomy should be immediately available and ready in the event of rapid deterioration, at the same time as intravenous (IV) infusion of third-generation cephalosporin or ampicillin/sulbactam, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) coverage. Though the rationale for empirical use of antibiotics is evident, the role of corticosteroids and of nebulized racemic epinephrine is controversial.

Death, airway obstruction, epiglottic abscess, necrotizing epiglottitis, and secondary infections (eg, pneumonia, cervical adenitis, septic arthritis, meningitis) are the potential complications that make this source of neck pain one not to be missed. If epiglottitis is suspected, the patient must be admitted to an intensive care setting.

Retropharyngeal Abscess

The retropharyngeal space, immediately behind the posterior pharynx and esophagus, extends from the base of the skull to the mediastinum. It lies anterior to the deep cervical fascia and is bound laterally by the carotid sheaths.30 Because it is fused down the midline, abscesses in this area tend to be unilateral. The space cannot be directly assessed by physical examination, and infections in this area are rare. Timely diagnosis demands consideration of retropharyngeal abscess in patients presenting with fever, neck stiffness, and sore throat. The potential for serious morbidity and mortality is related to the host of vital structures immediately adjacent to the retropharyngeal space. Complications include mediastinitis, carotid artery erosion, jugular vein thrombosis, pericarditis, epidural abscess, sepsis, and airway compromise.

Most cases are typically observed in children younger than age 6 years. In this pediatric population, the retropharyngeal space has two parallel chains of lymph nodes draining the nose, sinuses, and pharynx; retropharyngeal abscesses usually occur as a suppurative extension from infections of these upper airway structures structures. Penetrating trauma, eg, from objects held in the mouth, is another possible cause. These nodes atrophy around 6 years of age; thereafter, the main cause of retropharyngeal abscess is purulent extension of an adjacent (frequently odontogenic) infection or posterior pharyngeal trauma (eg, from a fish bone or instrumentation).31 As befits its origin with oral flora, cultures are almost always polymicrobial (eg, Streptococci viridans and pyogenes, Staphylococcus, H influenza, Klebsiella, anaerobes).

Although retropharyngeal abscess is considered a disease of childhood, like epiglottitis, its incidence in adults is increasing. 32 Presenting symptoms are signs of respiratory distress, such as wheezing, stridor, and drooling with impending airway obstruction from the expanding posterior pharyngeal mass. Late signs of the illness are respiratory failure due to airway obstruction and septic shock, but an astute clinician should recognize the entity long before these symptoms present. Early symptoms include fever, sore throat, odynophagia, and neck pain and stiffness (typically manifesting as a reluctance to turn the neck).33 Patients may also complain of feeling a lump in the throat or pain in the posterior neck or shoulder with swallowing.34 Ninety-seven percent of pediatric patients present with neck pain,32 which could manifest dramatically as torticollis. Most likely, a child will have a subtle reluctance to move his or her neck during the course of the physical examination. In addition, there may be posterior pharyngeal edema and/or a visible unilateral posterior pharyngeal bulge, cervical adenopathy, and a “croupy” cry or cough resembling a duck’s quack—the “cri du canard.”35 Definitive diagnosis is made using X-ray and/or CT. A lateral soft-tissue neck X-ray will demonstrate widening of the prevertebral soft tissues. CT with contrast provides a more definitive diagnosis, and is also useful to differentiate abscess (ie, a hypodense lesion with ring enhancement) from cellulitis.

Regarding treatment, empiric IV antibiotics must be started immediately and may alone prevent progression if the diagnosis is made before cellulitis has progressed to abscess. Intravenous clindamycin is a reasonable first-line antibiotic; other suggested drugs include a penicillin/ beta lactamase inhibitor, penicillin G plus metronidazole, and cefoxitin.36 Airway protection is mandatory, and an otolaryngologist should be consulted early. Because of the potential for sudden airway deterioration, the emergency physician must be prepared to establish a surgical airway.

Ludwig’s Angina

Ludwig’s angina derives its name from the German physician Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig, who first described this deadly, rapidly progressive, fascial space/ connective tissue gangrenous cellulitis of the floor of the mouth and adjoining neck in 1836. In a curious twist of fate, it is believed that Dr Ludwig died from this very disease that bears his name.37

Ninety percent of cases of Ludwig’s angina are odontogenic, often due to periapical abscesses. This condition may result secondary to any oral or parapharyngeal infection that spreads by continuity from the submandibular space into the contiguous sublingual and submental spaces. The potential for airway obstruction comes from elevation and displacement of the tongue, resulting in a mortality rate greater than 50% if untreated. Causative organisms mirror normal, polymicrobial oral flora and include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Bacteroides.38,23

Diagnosis of Ludwig’s angina is primarily clinical. Neck pain and swelling, dental pain, dysphagia, malaise, and fever, along with a protruding or elevated tongue, are typical. Submandibular swelling, which is seen in 95% of patients, develops in advanced cases into an intense “woody” induration above the hyoid bone that portends the impending airway crisis.39 If the patient is sufficiently clinically stable and able to lie flat, definitive diagnosis can be made with a contrastenhanced, soft-tissue neck CT (Figure 4), which can also evaluate for a drainable abscess, soft-tissue gas, and mediastinal extension; this modality can also define the extent of soft-tissue swelling and airway patency.

Airway management is the primary consideration because of its potential for rapid deterioration. Traditional management has been aggressive and surgical, with the standard being early tracheostomy. More recent reports have encouraged more conservative management when possible.40 Impending or actual airway compromise, as manifest by significant trismus, inability to flex the neck without compromising the airway, inability to protrude the tongue, or actual resting dyspnea demand that a surgical airway be readied at bedside until fiber optic nasotracheal intubation is secured.

Antibiotics must be given early and include coverage for gram-positive, gramnegative, and anaerobic organisms. Intravenous metronidazole and penicillin (cefazolin or clindamycin if patient has an allergy to penicillin) are commonly prescribed.38,23 Although controversial, administration of IV dexamethasone (8 mg to 12 mg) and nebulized epinephrine (1:1000, 1 mL diluted to 5 mL with normal saline) to reduce edema has been advocated. 41

Lemierre’s Syndrome Lemierre’s syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, was first described in 1936 by André Lemierre, who published a series of cases of previously healthy young adults in whom oropharyngeal infections were followed by “anaerobic postanginal septicaemias.”42 Most of these patients presented with sore throat (referred to as “angina” in “old skool” speak) and worsening pain and tenderness at the anterolateral neck, with pulmonary symptoms manifesting several days to 2 weeks later. The causative organism, Fusobacterium necrophorum, is a gram-negative anaerobe that is part of the normal commensal oropharyngeal flora. It invades the internal jugular (IJ) vein via the lateral pharyngeal space and releases a hemagglutinin that promotes thrombus formation in the IJ and, ultimately, metastatic septic emboli. These emboli typically invade the lungs and cause multiple nodular infiltrates and small pleural effusions. Unfortunately, as each case is unique, diagnosis is often delayed. Septic emboli can migrate to other sites and cause arthritis (hip, knee, shoulder, sacroiliac, and other joints), osteomyelitis, young adult with a history of recent sore throat and fever who subsequently developed neck pain and tenderness (with or without swelling) over the IJ, rigors, pulmonary infiltrates, and possibly other signs of septic emboli.

Doppler ultrasound or CT will show IJ thrombosis43 (Figure 5). Purulent discharge, if obtained, has a characteristic foul smell that has been likened to “limburger or overripe Camembert cheese.”44 Treatment is with high-dose IV penicillin and metronidazole or with clindamycin as single coverage. Heparin could potentially aid in dissemination of emboli, but it is used only when there is retrograde propagation of clot to the cavernous sinus.

With the routine antibiotic treatment of pharyngitis in the 1960s and 1970s, cases of Lemierre’s syndrome became so rare that it was referred to as the “forgotten disease.”45 Unfortunately, its incidence has increased over the past few years.43 It is unclear whether this rise is due to increasing antibiotic resistance or to an increasing resistance of clinicians to use antibiotics for “sore throats.”

Cervical Spinal Infections

Vertebral osteomyelitis, discitis, and spinal epidural abscess are rare in developed countries. Most cases stem from hematogenous seeding, skin abscesses, and urinary tract infections but can also originate from a host of other sites, including penetrating trauma and invasive spinal procedures (eg, lumbar punctures, epidural injections). 46,47 Cervical spine infections are associated with immune-compromising situations or conditions (eg, IV drug use, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, renal insufficiency, long-term use of systemic corticosteroids).

All three of these conditions present similarly, often as localized neck pain that grows more intense over a period of days to weeks and worsens with neck movement. Neurological signs ordinarily appear late in the course of the illness. Fever is a classic symptom but is not always present.48 There is usually tenderness over the involved spinous process. The development of motor or sensory loss suggests formation of an abscess,49 which can rapidly lead to further compressive symptoms and sepsis.

Leukocytosis may be absent but erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are often elevated. A CT scan with contrast is frequently required for diagnosis, though when available, MRI with IV gadolinium is the test of choice (Figure 6). Most cases are caused by S aureus, but antibiotic coverage for gram-positive organisms (including MRSA), gram-negative organisms, and anaerobes should be started as soon as blood cultures are drawn. Neurosurgery should be consulted emergently since, with cervical epidural abscess, neurological deterioration—even to the point of total paralysis—can develop in a matter of hours.50

Conclusion

Although most patients presenting to the ED with neck pain are musculoskeletal and associated with a traumatic event, other infrequent but potentially serious atraumatic causes may be present. Based on a patient’s symptoms, emergency physicians should also consider these conditions in the differential diagnosis to ensure rapid treatment to prevent further complications.

- Ammer C. The American heritage dictionary of idioms. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1997:489.

- Fusco MR, Harrigan MR. Cerebrovascular dissections—a review part I: spontaneous dissections. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(1):242-257.

- Rubinstein SM, Peerdeman SM, van Tulder MW, Riphagen I, Haldeman S. A systematic review of the risk factors for cervical artery dissection. Stroke.2005;36(7):1575-1580.

- Bergin M, Bird P, Wright A. Internal carotid artery dissection following canalith repositioning procedure. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124(5):575, 576.

- Brandt T, Grond-Ginsbach C. Spontaneous cervical artery dissection: from risk factors toward pathogenesis. Stroke. 2002;33(3):657,658.

- Arnold M, Cumurciuc R, Stapf C, Favrole P, Berthet K, Bousser MG. Pain as the only symptom of cervical artery dissection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(9):1021-1024.

- Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):898-906.

- Caplan LR. Dissections of brain-supplying arteries. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(1):34-42.

- Silbert PL, Mokri B, Schievink WI. Headache and neck pain in spontaneous internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1517-1522.

- Engelter ST, Brandt T, Debette S; Cervical Artery Dissection in Ischemic Stroke Patients (CADISP) Study Group. Antiplatelets versus anticoagulation in cervical artery dissection. Stroke. 2007;38(9):2605-2611.

- Arnold M, Bousser M, Fahrni G, et al. Vertebral artery dissection: presenting findings and predictors of outcome. Stroke. 2006;37(10):2499-2503.

- Hsieh CT, Chang CF, Lin EY, Tsai TH, Chiang YH, Ju DT. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas of cervical spine: report of 4 cases and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(6):736-740.

- Sei A, Nakamura T, Hashimoto N, Mizuta H, Sasaki A, Takagi K. Cervical spinal epidural hematoma with spontaneous remission. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4(2):234-237.

- Williams JM, Allegra JR. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(6):1368-1370.

- Demierre B, Unger PF, Bongioanni F. Sudden cervical pain: spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9(1):54-56.

- Broder J, L’Italien A. Evaluation and management of the patient with neck pain. In: Mattu A, Goyal DG eds. Emergency Medicine: Avoiding the Pitfalls and Improving the Outcomes. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, Inc; 2007:46-54. http://onlinelibrary. wiley.com/book/10.1002/9780470755938. Accessed November 15, 2013.

- Brodsky AE. Cervical angina. A correlative study with emphasis on the use of coronary arteriography. Spine. 1985;10(8):699-709.

- Hanflig SS. Pain in the shoulder girdle, arm and precordium due to cervical arthritis. JAMA. 1936;106(7):523-526.

- Goldberg R, Goff D, Cooper L, et al. Age and sex differences in presentation of symptoms among patients with acute coronary disease: the REACT Trial. Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment. Coron Artery Dis. 2000;11(5):399-407.

- Coventry LL, Finn J, Bremner AP. Sex differences in symptom presentation in acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 2011;40(6):477-491.

- Lipetz JS, Ledon J, Silber J. Severe coronary artery disease presenting with a chief complaint of cervical pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(9):716-720.

- Morens DM. Death of a president. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(24):1845-1849.

- Winters M. Evidence-based diagnosis and management of ENT emergencies. Medscape. 2007. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/551650_1. Accessed November 15, 2013.