User login

Q) Why do my patients with multiple sclerosis experience so much fatigue, and what can I do to help them?

Fatigue is an extremely common symptom of multiple sclerosis (MS) and one of the most disabling complications of the disease.1 More than 75% of patients with MS experience fatigue, which can worsen motor function, sleep quality, mood, and overall quality of life.1,2 Fatigue can also adversely affect employment; among patients with MS who reduce their work hours from full- to part-time, 90% do so because of fatigue.3

The

Patients with MS may have primary or secondary causes of fatigue. Primary fatigue is believed to result from the disease itself. Although it is not well understood, one hypothesis suggests that it is caused by an immune-related process involving inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration.7 Another theory relates it to impaired nerve conduction.8

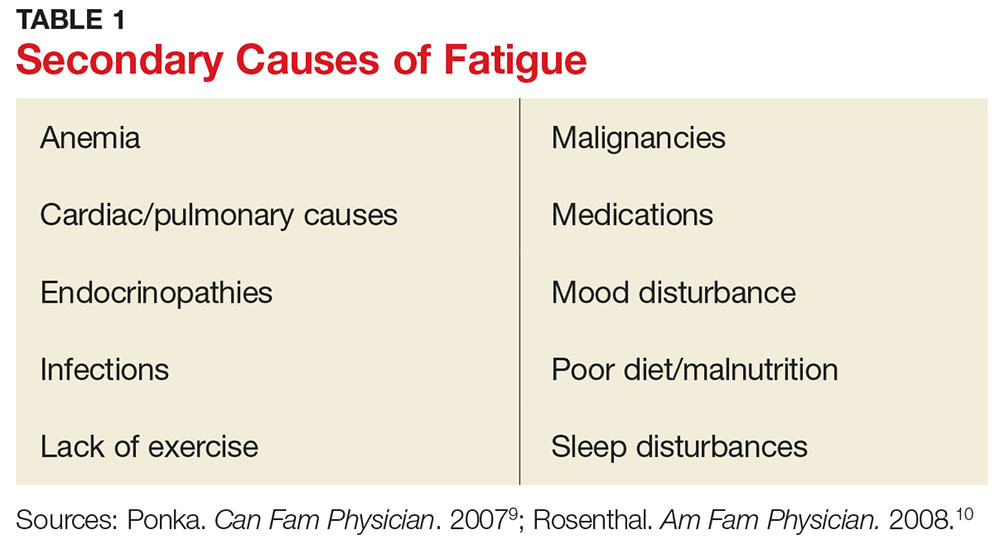

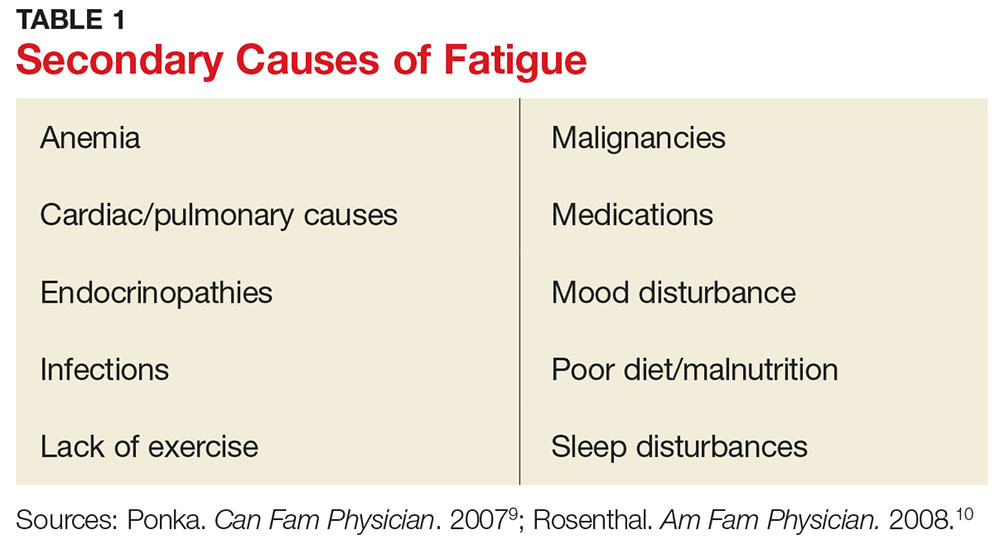

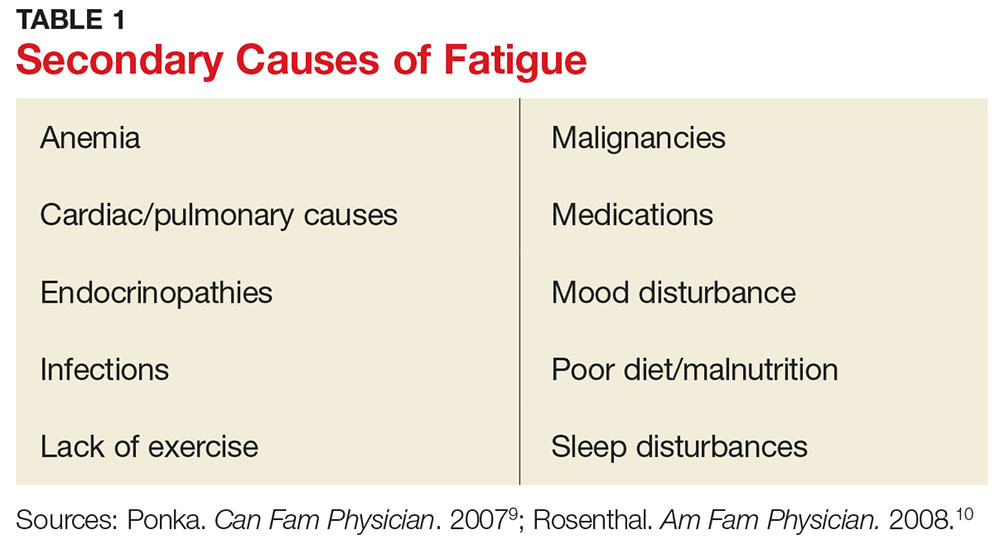

Secondary fatigue is unrelated to MS itself, and it is often treatable. Common causes include anemia, infection, or insomnia (see Table 1).9,10 These possibilities should be considered and ruled out in all patients with MS who complain of fatigue. A comprehensive history, exam, and evaluation performed by the clinician may help identify alternative reasons for fatigue.

Once any secondary causes have been addressed, primary fatigue should be evaluated and managed. One method for assessing the severity of fatigue and its impact on functional disability is to discuss it with the patient. The Fatigue Severity Scale can also be used as a measure; this self-assessment is quick, easy, and can be downloaded for free at www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf.11Identifying potential triggers of fatigue can help clinicians develop appropriate interventions. Heat intolerance is common and can precipitate or contribute to fatigue; cooling equipment can be a helpful solution (see Figure). Urinary tract infections frequently cause fatigue and can exacerbate many symptoms of MS. Bladder dysfunction and subsequent nocturnal wakening may contribute to the problem. Psychological stress is another common trigger; managing it can reduce fatigue.1,12 Screening for depression in patients with MS who complain of fatigue is imperative; if diagnosed, it must be addressed as the first line of treatment.1

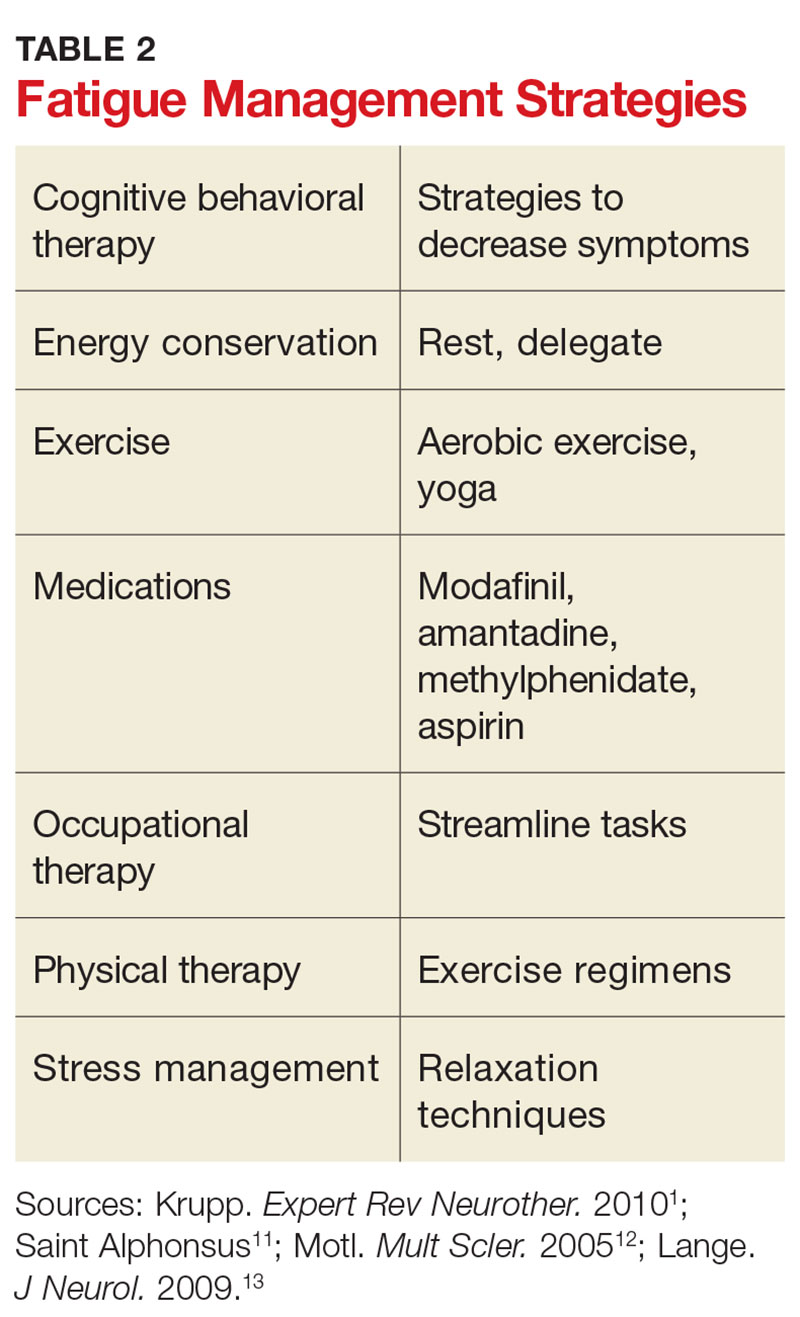

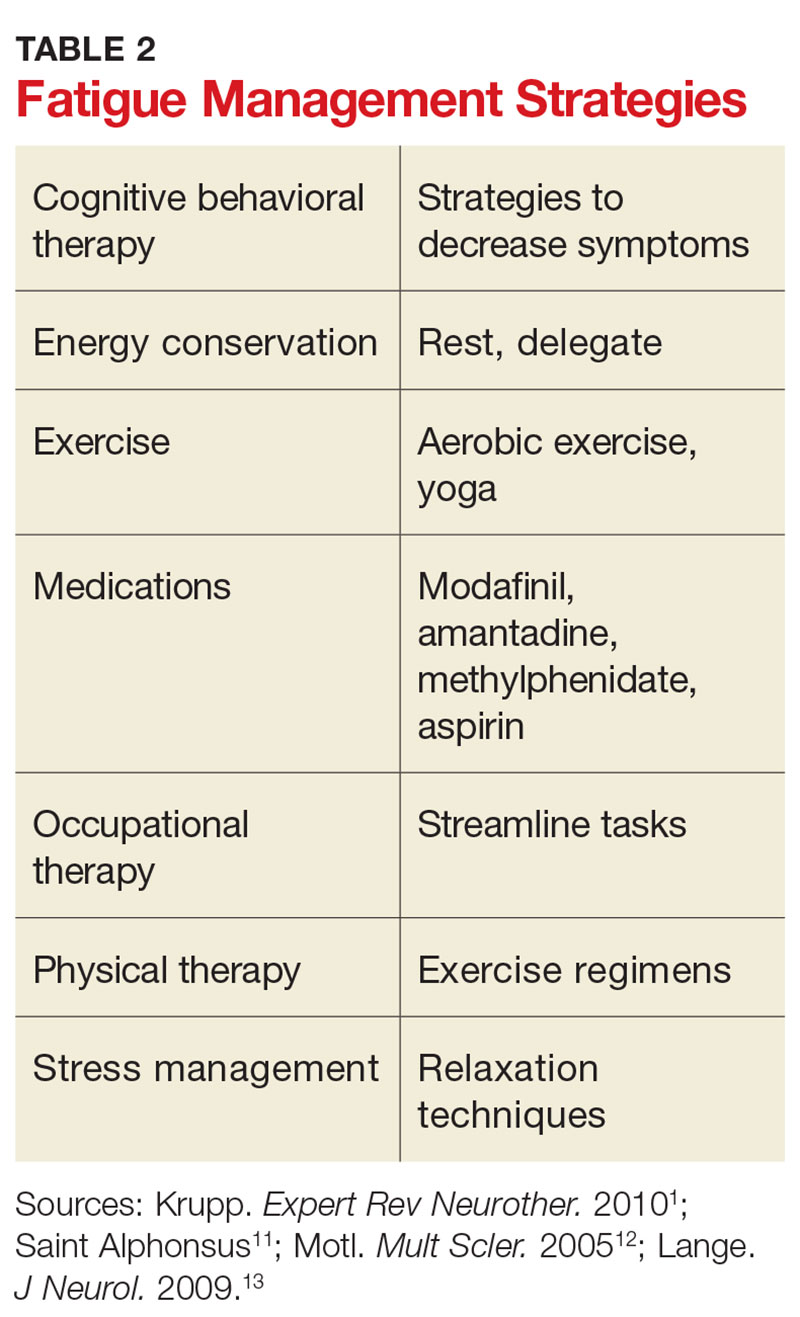

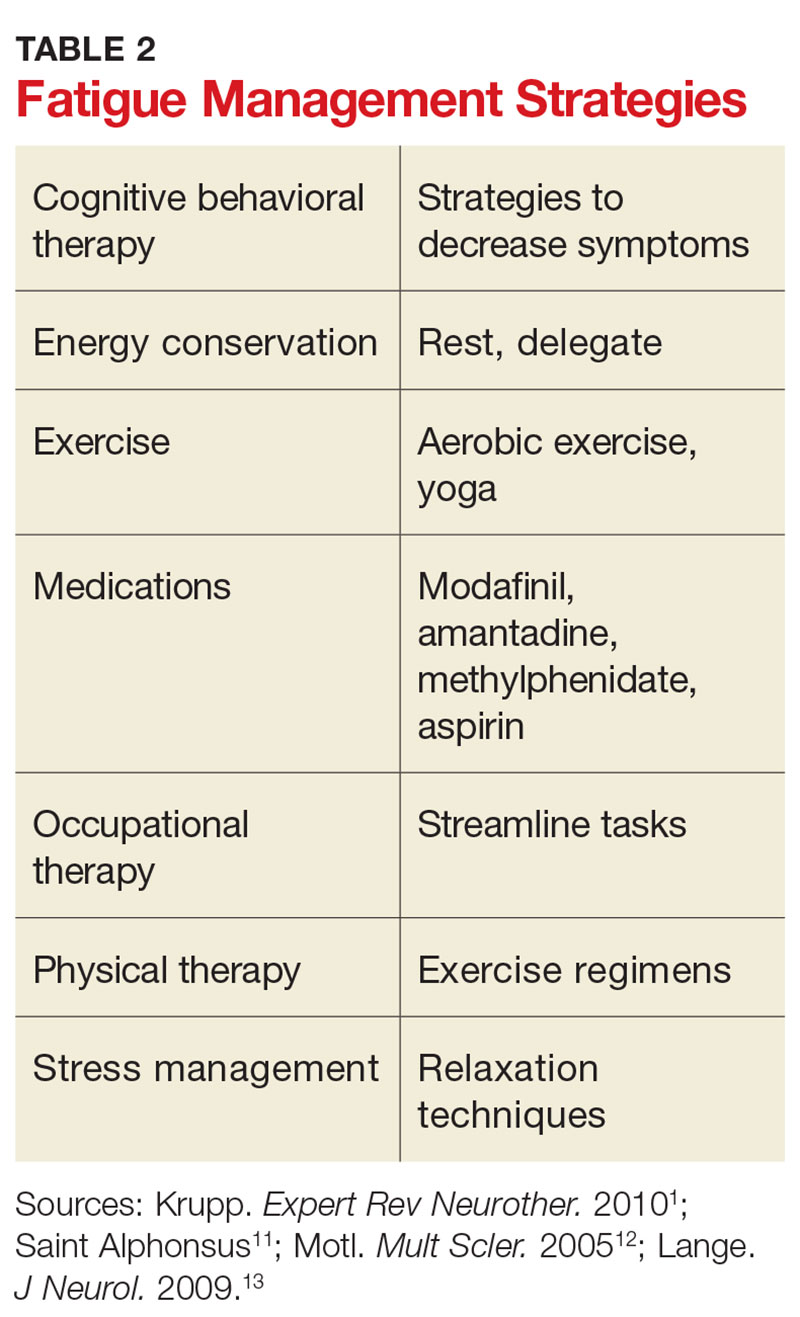

Other clinician-initiated intervention strategies include exercise, therapy, and medication. Modafinil is frequently prescribed for MS fatigue; small trials have demonstrated dramatic improvements with its use.13 Interestingly, aspirin has been shown to reduce fatigue in randomized controlled trials.14 This may be due to its indirect effects on neuroendocrine and autonomic responses, both of which are involved in the perception of fatigue.14 Additional interventions are listed in Table 2. As always, before prescribing any new medication, ensure that it is appropriate and that the patient’s other medical providers agree to the plan.

Counsel patients by emphasizing the importance of good sleep hygiene, a healthy diet, and avoidance of unhealthy habits. Taking an interdisciplinary approach can help patients with MS receive the best possible health care. While you may not be treating your patient’s disease, you will be managing much of his or her health care; treating the underlying causes of fatigue can significantly improve quality of life. —SA

Stephanie Agrella, MSN, RN, APRN, ANP-BC, MSCN

Director of Clinical Services, Multiple Scerlosis Clinic of Central Texas, Round Rock

1. Krupp B, Serafin D, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1437-1447.

2. Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):367-368.

3. Dennett SL, Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MK. The impact of multiple sclerosis on patient employment: a review of the medical literature. J Health Productivity. 2007;2(2):12-18.

4. Fatigue Guidelines Development Panel of the Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence-based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

5. Kalb R. Multiple Sclerosis: The Questions You Have—The Answers You Need. New York, NY: Demos; 2012.

6. Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(4):435-437.

7. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, Zettl UK. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: a review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(3):210-220.

8. Davis S, Wilson T, White A, Frohman E. Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol. 2016;109(5):1531-1537.

9. Ponka D, Kirlew M. Top 10 differential diagnoses in family medicine: fatigue. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(5):892.

10. Rosenthal TC, Majeroni BA, Pretorius R, Malik K. Fatigue: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(10):1173-1179.

11. Saint Alphonsus. Fatigue severity scale. www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2017.

12. Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459-463.

13. Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Liepert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2009; 256(4):645-650.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

Q) Why do my patients with multiple sclerosis experience so much fatigue, and what can I do to help them?

Fatigue is an extremely common symptom of multiple sclerosis (MS) and one of the most disabling complications of the disease.1 More than 75% of patients with MS experience fatigue, which can worsen motor function, sleep quality, mood, and overall quality of life.1,2 Fatigue can also adversely affect employment; among patients with MS who reduce their work hours from full- to part-time, 90% do so because of fatigue.3

The

Patients with MS may have primary or secondary causes of fatigue. Primary fatigue is believed to result from the disease itself. Although it is not well understood, one hypothesis suggests that it is caused by an immune-related process involving inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration.7 Another theory relates it to impaired nerve conduction.8

Secondary fatigue is unrelated to MS itself, and it is often treatable. Common causes include anemia, infection, or insomnia (see Table 1).9,10 These possibilities should be considered and ruled out in all patients with MS who complain of fatigue. A comprehensive history, exam, and evaluation performed by the clinician may help identify alternative reasons for fatigue.

Once any secondary causes have been addressed, primary fatigue should be evaluated and managed. One method for assessing the severity of fatigue and its impact on functional disability is to discuss it with the patient. The Fatigue Severity Scale can also be used as a measure; this self-assessment is quick, easy, and can be downloaded for free at www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf.11Identifying potential triggers of fatigue can help clinicians develop appropriate interventions. Heat intolerance is common and can precipitate or contribute to fatigue; cooling equipment can be a helpful solution (see Figure). Urinary tract infections frequently cause fatigue and can exacerbate many symptoms of MS. Bladder dysfunction and subsequent nocturnal wakening may contribute to the problem. Psychological stress is another common trigger; managing it can reduce fatigue.1,12 Screening for depression in patients with MS who complain of fatigue is imperative; if diagnosed, it must be addressed as the first line of treatment.1

Other clinician-initiated intervention strategies include exercise, therapy, and medication. Modafinil is frequently prescribed for MS fatigue; small trials have demonstrated dramatic improvements with its use.13 Interestingly, aspirin has been shown to reduce fatigue in randomized controlled trials.14 This may be due to its indirect effects on neuroendocrine and autonomic responses, both of which are involved in the perception of fatigue.14 Additional interventions are listed in Table 2. As always, before prescribing any new medication, ensure that it is appropriate and that the patient’s other medical providers agree to the plan.

Counsel patients by emphasizing the importance of good sleep hygiene, a healthy diet, and avoidance of unhealthy habits. Taking an interdisciplinary approach can help patients with MS receive the best possible health care. While you may not be treating your patient’s disease, you will be managing much of his or her health care; treating the underlying causes of fatigue can significantly improve quality of life. —SA

Stephanie Agrella, MSN, RN, APRN, ANP-BC, MSCN

Director of Clinical Services, Multiple Scerlosis Clinic of Central Texas, Round Rock

Q) Why do my patients with multiple sclerosis experience so much fatigue, and what can I do to help them?

Fatigue is an extremely common symptom of multiple sclerosis (MS) and one of the most disabling complications of the disease.1 More than 75% of patients with MS experience fatigue, which can worsen motor function, sleep quality, mood, and overall quality of life.1,2 Fatigue can also adversely affect employment; among patients with MS who reduce their work hours from full- to part-time, 90% do so because of fatigue.3

The

Patients with MS may have primary or secondary causes of fatigue. Primary fatigue is believed to result from the disease itself. Although it is not well understood, one hypothesis suggests that it is caused by an immune-related process involving inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration.7 Another theory relates it to impaired nerve conduction.8

Secondary fatigue is unrelated to MS itself, and it is often treatable. Common causes include anemia, infection, or insomnia (see Table 1).9,10 These possibilities should be considered and ruled out in all patients with MS who complain of fatigue. A comprehensive history, exam, and evaluation performed by the clinician may help identify alternative reasons for fatigue.

Once any secondary causes have been addressed, primary fatigue should be evaluated and managed. One method for assessing the severity of fatigue and its impact on functional disability is to discuss it with the patient. The Fatigue Severity Scale can also be used as a measure; this self-assessment is quick, easy, and can be downloaded for free at www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf.11Identifying potential triggers of fatigue can help clinicians develop appropriate interventions. Heat intolerance is common and can precipitate or contribute to fatigue; cooling equipment can be a helpful solution (see Figure). Urinary tract infections frequently cause fatigue and can exacerbate many symptoms of MS. Bladder dysfunction and subsequent nocturnal wakening may contribute to the problem. Psychological stress is another common trigger; managing it can reduce fatigue.1,12 Screening for depression in patients with MS who complain of fatigue is imperative; if diagnosed, it must be addressed as the first line of treatment.1

Other clinician-initiated intervention strategies include exercise, therapy, and medication. Modafinil is frequently prescribed for MS fatigue; small trials have demonstrated dramatic improvements with its use.13 Interestingly, aspirin has been shown to reduce fatigue in randomized controlled trials.14 This may be due to its indirect effects on neuroendocrine and autonomic responses, both of which are involved in the perception of fatigue.14 Additional interventions are listed in Table 2. As always, before prescribing any new medication, ensure that it is appropriate and that the patient’s other medical providers agree to the plan.

Counsel patients by emphasizing the importance of good sleep hygiene, a healthy diet, and avoidance of unhealthy habits. Taking an interdisciplinary approach can help patients with MS receive the best possible health care. While you may not be treating your patient’s disease, you will be managing much of his or her health care; treating the underlying causes of fatigue can significantly improve quality of life. —SA

Stephanie Agrella, MSN, RN, APRN, ANP-BC, MSCN

Director of Clinical Services, Multiple Scerlosis Clinic of Central Texas, Round Rock

1. Krupp B, Serafin D, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1437-1447.

2. Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):367-368.

3. Dennett SL, Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MK. The impact of multiple sclerosis on patient employment: a review of the medical literature. J Health Productivity. 2007;2(2):12-18.

4. Fatigue Guidelines Development Panel of the Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence-based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

5. Kalb R. Multiple Sclerosis: The Questions You Have—The Answers You Need. New York, NY: Demos; 2012.

6. Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(4):435-437.

7. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, Zettl UK. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: a review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(3):210-220.

8. Davis S, Wilson T, White A, Frohman E. Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol. 2016;109(5):1531-1537.

9. Ponka D, Kirlew M. Top 10 differential diagnoses in family medicine: fatigue. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(5):892.

10. Rosenthal TC, Majeroni BA, Pretorius R, Malik K. Fatigue: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(10):1173-1179.

11. Saint Alphonsus. Fatigue severity scale. www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2017.

12. Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459-463.

13. Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Liepert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2009; 256(4):645-650.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

1. Krupp B, Serafin D, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1437-1447.

2. Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):367-368.

3. Dennett SL, Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MK. The impact of multiple sclerosis on patient employment: a review of the medical literature. J Health Productivity. 2007;2(2):12-18.

4. Fatigue Guidelines Development Panel of the Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence-based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

5. Kalb R. Multiple Sclerosis: The Questions You Have—The Answers You Need. New York, NY: Demos; 2012.

6. Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(4):435-437.

7. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, Zettl UK. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: a review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(3):210-220.

8. Davis S, Wilson T, White A, Frohman E. Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol. 2016;109(5):1531-1537.

9. Ponka D, Kirlew M. Top 10 differential diagnoses in family medicine: fatigue. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(5):892.

10. Rosenthal TC, Majeroni BA, Pretorius R, Malik K. Fatigue: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(10):1173-1179.

11. Saint Alphonsus. Fatigue severity scale. www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2017.

12. Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459-463.

13. Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Liepert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2009; 256(4):645-650.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.