User login

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

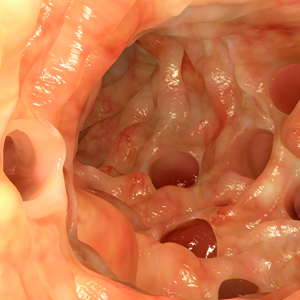

A 58-year-old man presents to your office with a 2-day history of moderate (6/10) left lower quadrant pain, mild fever (none currently), 2 episodes of vomiting, no diarrhea, and no relief with over-the-counter medications. You suspect diverticulitis and obtain an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, which shows mild, uncomplicated (Hinchey stage 1a) diverticulitis.

How would you treat him?

Diverticulitis is common; about 200,000 people per year are admitted to the hospital because of diverticulitis in the United States.2,3 Health care providers typically treat diverticular disease with antibiotics and bowel rest.2,3 While severe forms of diverticulitis often require parenteral antibiotics and/or surgery, practitioners are increasingly managing the condition with oral antibiotics.4

One previous randomized control trial (RCT; N=623) found that antibiotic treatment (compared with no antibiotic treatment) for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis did not speed recovery or prevent complications (perforation or abscess formation) or recurrence at 12 months.5 The study’s strengths included limiting enrollment to people with CT-proven diverticulitis, using a good randomization and concealment process, and employing intention-to-treat analysis. The study was limited by a lack of a standardized antibiotic regimen across centers, previous diverticulitis diagnoses in 40% of patients, non-uniform follow-up processes to confirm anatomic resolution, and the lack of assessment to confirm resolution.5

STUDY SUMMARY

RCT finds that watchful waiting is just as effective as antibiotic Tx

This newer study was a single-blind RCT that compared treatment with antibiotics to observation among 528 adult patients in the Netherlands. Patients were enrolled if they had CT-proven, primary, left-sided, uncomplicated acute diverticulitis (Hinchey stage 1a and 1b).1 (The Hinchey classification is based on radiologic findings, with 0 for clinical diverticulitis only, 1a for confined pericolic inflammation or phlegmon, and 1b for pericolic or mesocolic abscess.6) Exclusion criteria included suspicion of colonic cancer by CT or ultrasound (US), previous CT/US-proven diverticulitis, sepsis, pregnancy, or antibiotic use in the previous 4 weeks.1

Observational vs antibiotic treatment. Enrolled patients were randomized to receive IV administration of amoxicillin-clavulanate 1200 mg 4 times daily for at least 48 hours followed by 625 mg PO 3 times daily for 10 total days of antibiotic treatment (n=266) or to be observed (n=262). Computerized randomization, with a random varying block size and stratified by Hinchey classification and center, was performed, and allocation was concealed. The investigators were masked to the allocation until all analyses were completed.1

The primary outcome was the time to functional recovery (resumption of pre-illness work activities) during a 6-month follow-up period. Secondary outcomes included hospital readmission rate; complicated, ongoing, and recurrent diverticulitis; sigmoid resection; other nonsurgical intervention; antibiotic treatment adverse effects; and all-cause mortality.

Continue to: Results

Results. Median recovery time for observational treatment was not inferior to antibiotic treatment (14 days vs 12 days; P=.15; hazard ratio [HR] for functional recovery=0.91; lower limit of 1-sided 95% confidence interval, 0.78). Observation was not inferior to antibiotics for any of the secondary endpoints at 6 and 12 months of follow-up (complicated diverticulitis, 3.8% vs 2.6%, respectively; P=.377), recurrent diverticulitis (3.4% vs 3%; P=.494), readmission (17.6% vs 12%; P=.148), or adverse events (48.5% vs 54.5%; P=.221). Initial hospitalization length of stay was shorter in the observation group (2 vs 3 days; P=.006). The researchers conducted a 24-month telephone follow-up, but no differences from the 12-month follow-up were noted.1

WHAT’S NEW

A study that looks at a true patient-oriented outcome

Previous studies of treatment options for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis looked at short-term outcomes, or at readmission, recurrence, and surgical intervention rate, or requirement for percutaneous drainage.7,8 This study is the first one to look at functional return to work (a true patient-oriented outcome). And it is the only study to look out to 24 months to gauge long-term outcomes with observational treatment.

CAVEATS

Can’t generalize findings to patients with worse forms of diverticulitis

It is worth noting that the findings of this study apply only to the mildest form of CT-proven acute diverticulitis (those patients classified as having Hinchey 1a disease), and is not generalizable to patients with more severe forms. Not enough patients with Hinchey 1b acute diverticulitis were enrolled in the study to reach any conclusions about treatment.

Various guidelines issued outside the United States recommend antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis; however, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) indicates that antibiotics should be used selectively.1,9,10 This recommendation was based on an emerging understanding that diverticulitis maybe more inflammatory than infectious in nature. The AGA guideline authors acknowledge that their conclusion was based on low-quality evidence.9

Continuet to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

We see no challenges to implementing this recommendation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Daniels L, Ünlü Ç, de Korte N, et al, for the Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of observational versus antibiotic treatment for a first episode of CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104:52-61.

2. Wheat CL, Strate LL. Trends in hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding in the United States from 2000 to 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:96-103.e1.

3. Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

4. Shabanzadeh DM, Wille-Jørgensen P. Antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD009092.

5. Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:532-539.

6. Klarenbeek BR, de Korte N, van der Peet DL, et al. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:207-214.

7. Tandon A, Fretwell VL, Nunes QM, et al. Antibiotics versus no antibiotics in the treatment of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2018 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/codi.14013.

8. Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:284-294.

9. Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the management of acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1944-1949.

10. Sartelli M, Viale P, Catena F, et al. 2013 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:3.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 58-year-old man presents to your office with a 2-day history of moderate (6/10) left lower quadrant pain, mild fever (none currently), 2 episodes of vomiting, no diarrhea, and no relief with over-the-counter medications. You suspect diverticulitis and obtain an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, which shows mild, uncomplicated (Hinchey stage 1a) diverticulitis.

How would you treat him?

Diverticulitis is common; about 200,000 people per year are admitted to the hospital because of diverticulitis in the United States.2,3 Health care providers typically treat diverticular disease with antibiotics and bowel rest.2,3 While severe forms of diverticulitis often require parenteral antibiotics and/or surgery, practitioners are increasingly managing the condition with oral antibiotics.4

One previous randomized control trial (RCT; N=623) found that antibiotic treatment (compared with no antibiotic treatment) for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis did not speed recovery or prevent complications (perforation or abscess formation) or recurrence at 12 months.5 The study’s strengths included limiting enrollment to people with CT-proven diverticulitis, using a good randomization and concealment process, and employing intention-to-treat analysis. The study was limited by a lack of a standardized antibiotic regimen across centers, previous diverticulitis diagnoses in 40% of patients, non-uniform follow-up processes to confirm anatomic resolution, and the lack of assessment to confirm resolution.5

STUDY SUMMARY

RCT finds that watchful waiting is just as effective as antibiotic Tx

This newer study was a single-blind RCT that compared treatment with antibiotics to observation among 528 adult patients in the Netherlands. Patients were enrolled if they had CT-proven, primary, left-sided, uncomplicated acute diverticulitis (Hinchey stage 1a and 1b).1 (The Hinchey classification is based on radiologic findings, with 0 for clinical diverticulitis only, 1a for confined pericolic inflammation or phlegmon, and 1b for pericolic or mesocolic abscess.6) Exclusion criteria included suspicion of colonic cancer by CT or ultrasound (US), previous CT/US-proven diverticulitis, sepsis, pregnancy, or antibiotic use in the previous 4 weeks.1

Observational vs antibiotic treatment. Enrolled patients were randomized to receive IV administration of amoxicillin-clavulanate 1200 mg 4 times daily for at least 48 hours followed by 625 mg PO 3 times daily for 10 total days of antibiotic treatment (n=266) or to be observed (n=262). Computerized randomization, with a random varying block size and stratified by Hinchey classification and center, was performed, and allocation was concealed. The investigators were masked to the allocation until all analyses were completed.1

The primary outcome was the time to functional recovery (resumption of pre-illness work activities) during a 6-month follow-up period. Secondary outcomes included hospital readmission rate; complicated, ongoing, and recurrent diverticulitis; sigmoid resection; other nonsurgical intervention; antibiotic treatment adverse effects; and all-cause mortality.

Continue to: Results

Results. Median recovery time for observational treatment was not inferior to antibiotic treatment (14 days vs 12 days; P=.15; hazard ratio [HR] for functional recovery=0.91; lower limit of 1-sided 95% confidence interval, 0.78). Observation was not inferior to antibiotics for any of the secondary endpoints at 6 and 12 months of follow-up (complicated diverticulitis, 3.8% vs 2.6%, respectively; P=.377), recurrent diverticulitis (3.4% vs 3%; P=.494), readmission (17.6% vs 12%; P=.148), or adverse events (48.5% vs 54.5%; P=.221). Initial hospitalization length of stay was shorter in the observation group (2 vs 3 days; P=.006). The researchers conducted a 24-month telephone follow-up, but no differences from the 12-month follow-up were noted.1

WHAT’S NEW

A study that looks at a true patient-oriented outcome

Previous studies of treatment options for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis looked at short-term outcomes, or at readmission, recurrence, and surgical intervention rate, or requirement for percutaneous drainage.7,8 This study is the first one to look at functional return to work (a true patient-oriented outcome). And it is the only study to look out to 24 months to gauge long-term outcomes with observational treatment.

CAVEATS

Can’t generalize findings to patients with worse forms of diverticulitis

It is worth noting that the findings of this study apply only to the mildest form of CT-proven acute diverticulitis (those patients classified as having Hinchey 1a disease), and is not generalizable to patients with more severe forms. Not enough patients with Hinchey 1b acute diverticulitis were enrolled in the study to reach any conclusions about treatment.

Various guidelines issued outside the United States recommend antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis; however, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) indicates that antibiotics should be used selectively.1,9,10 This recommendation was based on an emerging understanding that diverticulitis maybe more inflammatory than infectious in nature. The AGA guideline authors acknowledge that their conclusion was based on low-quality evidence.9

Continuet to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

We see no challenges to implementing this recommendation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 58-year-old man presents to your office with a 2-day history of moderate (6/10) left lower quadrant pain, mild fever (none currently), 2 episodes of vomiting, no diarrhea, and no relief with over-the-counter medications. You suspect diverticulitis and obtain an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, which shows mild, uncomplicated (Hinchey stage 1a) diverticulitis.

How would you treat him?

Diverticulitis is common; about 200,000 people per year are admitted to the hospital because of diverticulitis in the United States.2,3 Health care providers typically treat diverticular disease with antibiotics and bowel rest.2,3 While severe forms of diverticulitis often require parenteral antibiotics and/or surgery, practitioners are increasingly managing the condition with oral antibiotics.4

One previous randomized control trial (RCT; N=623) found that antibiotic treatment (compared with no antibiotic treatment) for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis did not speed recovery or prevent complications (perforation or abscess formation) or recurrence at 12 months.5 The study’s strengths included limiting enrollment to people with CT-proven diverticulitis, using a good randomization and concealment process, and employing intention-to-treat analysis. The study was limited by a lack of a standardized antibiotic regimen across centers, previous diverticulitis diagnoses in 40% of patients, non-uniform follow-up processes to confirm anatomic resolution, and the lack of assessment to confirm resolution.5

STUDY SUMMARY

RCT finds that watchful waiting is just as effective as antibiotic Tx

This newer study was a single-blind RCT that compared treatment with antibiotics to observation among 528 adult patients in the Netherlands. Patients were enrolled if they had CT-proven, primary, left-sided, uncomplicated acute diverticulitis (Hinchey stage 1a and 1b).1 (The Hinchey classification is based on radiologic findings, with 0 for clinical diverticulitis only, 1a for confined pericolic inflammation or phlegmon, and 1b for pericolic or mesocolic abscess.6) Exclusion criteria included suspicion of colonic cancer by CT or ultrasound (US), previous CT/US-proven diverticulitis, sepsis, pregnancy, or antibiotic use in the previous 4 weeks.1

Observational vs antibiotic treatment. Enrolled patients were randomized to receive IV administration of amoxicillin-clavulanate 1200 mg 4 times daily for at least 48 hours followed by 625 mg PO 3 times daily for 10 total days of antibiotic treatment (n=266) or to be observed (n=262). Computerized randomization, with a random varying block size and stratified by Hinchey classification and center, was performed, and allocation was concealed. The investigators were masked to the allocation until all analyses were completed.1

The primary outcome was the time to functional recovery (resumption of pre-illness work activities) during a 6-month follow-up period. Secondary outcomes included hospital readmission rate; complicated, ongoing, and recurrent diverticulitis; sigmoid resection; other nonsurgical intervention; antibiotic treatment adverse effects; and all-cause mortality.

Continue to: Results

Results. Median recovery time for observational treatment was not inferior to antibiotic treatment (14 days vs 12 days; P=.15; hazard ratio [HR] for functional recovery=0.91; lower limit of 1-sided 95% confidence interval, 0.78). Observation was not inferior to antibiotics for any of the secondary endpoints at 6 and 12 months of follow-up (complicated diverticulitis, 3.8% vs 2.6%, respectively; P=.377), recurrent diverticulitis (3.4% vs 3%; P=.494), readmission (17.6% vs 12%; P=.148), or adverse events (48.5% vs 54.5%; P=.221). Initial hospitalization length of stay was shorter in the observation group (2 vs 3 days; P=.006). The researchers conducted a 24-month telephone follow-up, but no differences from the 12-month follow-up were noted.1

WHAT’S NEW

A study that looks at a true patient-oriented outcome

Previous studies of treatment options for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis looked at short-term outcomes, or at readmission, recurrence, and surgical intervention rate, or requirement for percutaneous drainage.7,8 This study is the first one to look at functional return to work (a true patient-oriented outcome). And it is the only study to look out to 24 months to gauge long-term outcomes with observational treatment.

CAVEATS

Can’t generalize findings to patients with worse forms of diverticulitis

It is worth noting that the findings of this study apply only to the mildest form of CT-proven acute diverticulitis (those patients classified as having Hinchey 1a disease), and is not generalizable to patients with more severe forms. Not enough patients with Hinchey 1b acute diverticulitis were enrolled in the study to reach any conclusions about treatment.

Various guidelines issued outside the United States recommend antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis; however, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) indicates that antibiotics should be used selectively.1,9,10 This recommendation was based on an emerging understanding that diverticulitis maybe more inflammatory than infectious in nature. The AGA guideline authors acknowledge that their conclusion was based on low-quality evidence.9

Continuet to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

We see no challenges to implementing this recommendation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Daniels L, Ünlü Ç, de Korte N, et al, for the Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of observational versus antibiotic treatment for a first episode of CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104:52-61.

2. Wheat CL, Strate LL. Trends in hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding in the United States from 2000 to 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:96-103.e1.

3. Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

4. Shabanzadeh DM, Wille-Jørgensen P. Antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD009092.

5. Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:532-539.

6. Klarenbeek BR, de Korte N, van der Peet DL, et al. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:207-214.

7. Tandon A, Fretwell VL, Nunes QM, et al. Antibiotics versus no antibiotics in the treatment of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2018 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/codi.14013.

8. Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:284-294.

9. Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the management of acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1944-1949.

10. Sartelli M, Viale P, Catena F, et al. 2013 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:3.

1. Daniels L, Ünlü Ç, de Korte N, et al, for the Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of observational versus antibiotic treatment for a first episode of CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104:52-61.

2. Wheat CL, Strate LL. Trends in hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding in the United States from 2000 to 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:96-103.e1.

3. Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

4. Shabanzadeh DM, Wille-Jørgensen P. Antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD009092.

5. Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:532-539.

6. Klarenbeek BR, de Korte N, van der Peet DL, et al. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:207-214.

7. Tandon A, Fretwell VL, Nunes QM, et al. Antibiotics versus no antibiotics in the treatment of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2018 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/codi.14013.

8. Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:284-294.

9. Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the management of acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1944-1949.

10. Sartelli M, Viale P, Catena F, et al. 2013 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:3.

PRACTICE CHANGER

For mild, computed tomography-proven acute diverticulitis, consider observation only instead of antibiotic therapy.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single randomized controlled trial.

Daniels L, Ünlü Ç, de Korte N, et al, for the Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of observational versus antibiotic treatment for a first episode of CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104:52-61.1