User login

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

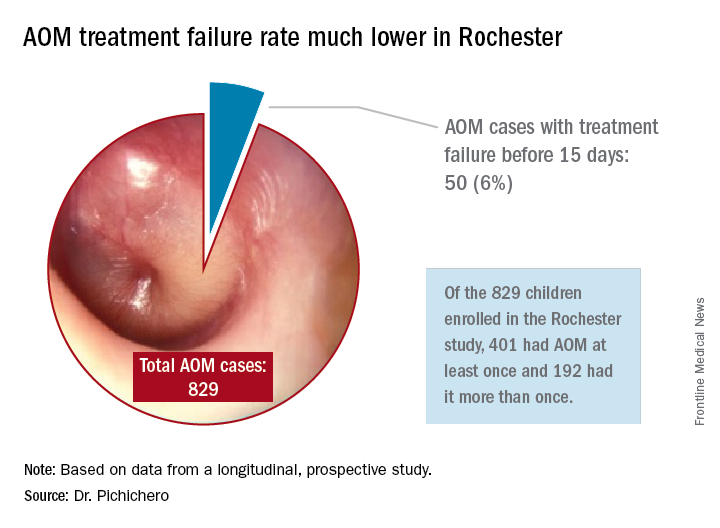

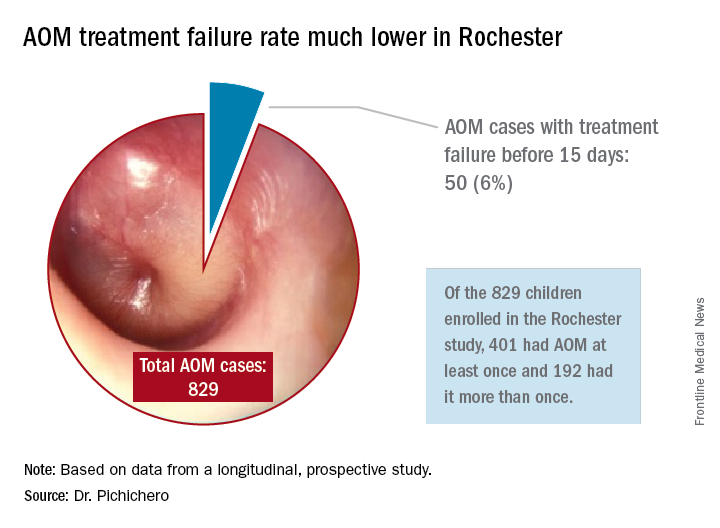

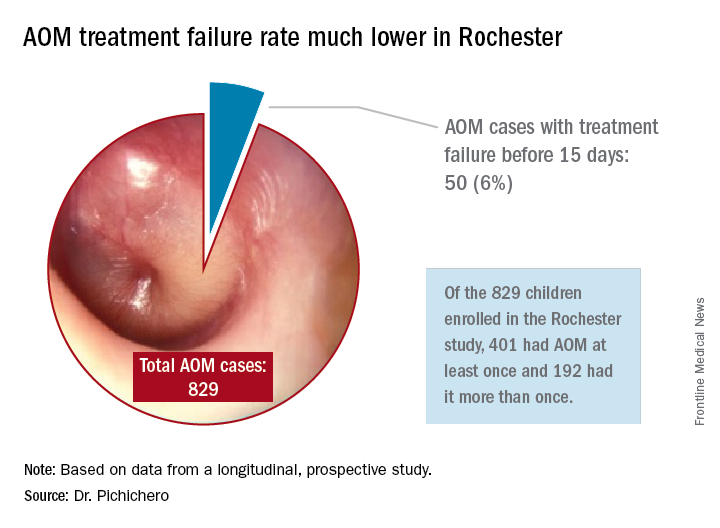

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.