User login

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Where I practice, most health care plans won’t pay for certain medications without giving prior authorization (PA). Completing PA forms and making telephone calls take up time that could be better spent treating patients. I’m tempted to set a new policy of not doing PAs. If I do, might I face legal trouble?

Submitted by “Dr. A”

If you provide clinical care, you’ve probably dealt with third-party payers who require prior authorization (PA) before they will pay for certain treatments. Dr. A is not alone in feeling exasperated about the time it takes to complete a PA.1 After spending several hours each month waiting on hold and wading through stacks of paperwork, you may feel like Dr. A and consider refusing to do any more PAs.

But is Dr. A’s proposed solution a good idea? To address this question and the frustration that lies behind it, we’ll take a cue from Italian film director Sergio Leone and discuss:

• how PAs affect psychiatric care: the good, the bad, and the ugly

• potential exposure to professional liability and ethics complaints that might result from refusing or failing to seek PA

• strategies to reduce the burden of PAs while providing efficient, effective care.

The good

Recent decades have witnessed huge increases in spending on prescription medication. Psychotropics are no exception; state Medicaid spending for anti-psychotic medication grew from <$1 billion in 1995 to >$5.5 billion in 2005.2

Requiring a PA for expensive drugs is one way that third-party payers try to rein in costs and hold down insurance premiums. Imposing financial constraints often is just one aim of a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) program. Insurers also justify PBMs by pointing out that feedback to practitioners whose prescribing falls well outside the norm—in the form of mailed warnings, physician second opinions, or pharmacist consultation—can improve patient safety and encourage appropriate treatment options for enrolled patients.3,4 Examples of such benefits include reducing overuse of prescription opioids5 and antipsychotics among children,3 misuse of buprenorphine,6 and adverse effects from potentially inappropriate prescriptions.7

The bad

The bad news for doctors: Cost savings for payers come at the expense of providers and their practices, in the form of time spent doing paperwork and talking on the phone to complete PAs or contest PA decisions.8 Addressing PA requests costs an estimated $83,000 per physician per year. The total administrative burden for all 835,000 physicians who practice in the United States therefore is 868,000,000 hours, or $69 billion annually.9

To make matters worse, PA requirements may increase the overall cost of care. After Georgia Medicaid instituted PA requirements for second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), average monthly per member drug costs fell $19.62, but average monthly outpatient treatment costs rose $31.59 per member.10 Pharmacy savings that result from requiring PAs for SGAs can be offset quickly by small increases in the hospitalization rate or emergency department visits.9,11

The ugly

Many physicians believe that the PA process undermines patient care by decreasing time devoted to direct patient contact, incentivizing suboptimal treatment, and limiting medication access.1,12,13 But do any data support this belief? Do PAs impede treatment for vulnerable persons with severe mental illnesses?

The answer, some studies suggest, is “Yes.” A Maine Medicaid PA policy slowed initiation of treatment for bipolar disorder by reducing the rate of starting non-preferred medications, although the same policy had no impact on patients already receiving treatment.14 Another study examined the effect of PA processes for inpatient psychiatry treatment and found that patients were less likely to be admitted on weekends, probably because PA review was not available on those days.15 A third study showed that PA requirements and resulting impediments to getting refills were correlated with medication discontinuation by patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which can increase the risk of decompensation, work-related problems, and hospitalization.16

Problems with PAs

Whether they are helpful or counterproductive, PAs are a practice reality. Dr. A’s proposed solution sounds appealing, but it might create ethical and legal problems.

Among the fundamental elements of ethical medical practice is physicians’ obligation to give patients “guidance … as to the optimal course of action” and to “advocate for patients in dealing with third parties when appropriate.”17 It’s fine for psychiatrists to consider prescribing treatments that patients’ health care coverage favors, but we also have to help patients weigh and evaluate costs, particularly when patients’ circumstances and medical interests militate strongly for options that third-party payers balk at paying for. Patients’ interests—not what’s expedient—are always physicians’ foremost concern.18

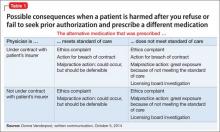

Beyond purely ethical considerations, you might face legal consequences if you refuse or fail to seek PAs for what you think is the proper medication. As Table 1 shows, one key factor is whether you are under contract with the patient’s insurance carrier; if you are, failure to seek a PA when appropriate may constitute a breach of the contract (Donna Vanderpool, written communication, October 5, 2014).

If the prescribed medication does not meet the standard of care and your patient suffers some harm, a licensing board complaint and investigation are possible. You also face exposure to a medical malpractice action. Although we do not know of any instances in which such an action has succeeded, 2 recent court decisions suggest that harm to a patient stemmed from failing to seek PA for a medication could constitute grounds for a lawsuit.19,20 Efforts to contain medical costs have been around for decades, and courts have held that physicians, third-party payers, and utilization review intermediaries are bound by “the standard of reasonable community practice”21 and should not let cost limitations “corrupt medical judgment.”22 Physicians who do not appeal limitations at odds with their medical judgment might bear responsibility for any injuries that occur.18,22

Managing PA requests

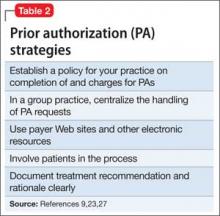

Given the inevitability of encountering PA requests and your ethical and professional obligations to help patients, what can you do (Table 29,23,27)?

Some practitioners charge patients for time spent completing PAs.23 Although physicians should “complete without charge the appropriate ‘simplified’ insurance claim form as a part of service to the patient;” they also may consider “a charge for more complex or multiple forms … in conformity with local custom.”24 Legally, physicians’ contracts with insurance panels may preclude charging such fees, but if a patient is being seen out of network, the physician does not have a contractual obligation and may charge.9 If your practice setting lets you choose which insurances you accept, the impact and burden of seeking PAs is a factor to consider when deciding whether to participate in a particular panel.23

In an interesting twist, an Ohio physician successfully sued a medical insurance administrator for the cost of his time responding to PA inquiries.25 Reasoning that the insurance administrator “should expect to pay for the reasonable value of” the doctor’s time because the PAs “were solely intended for the benefit of the insurance administrator” or parties whom the administrator served, the judge awarded the doctor $187.50 plus 8% interest.

Considerations that are more practical relate to how to triage and address the volume of PA requests. Some large medical practices centralize PAs and try to set up pre-approved plans of care or blanket approvals for frequently encountered conditions. Centralization also allows one key administrative assistant to develop skills in processing PA requests and to build relationships with payers.26

The administrative assistant also can compile lists of preferred alternative medications, PA forms, and payer Web sites. Using and submitting requests through payer Web sites can speed up PA processing, which saves time and money.27 As electronic health records improve, they may incorporate patients’ formularies and provide automatic alerts for required PAs.23

Patients should be involved, too. They can help to obtain relevant formulary information and to weigh alternative therapies. You can help them understand your role in the PA process, the reasoning behind your treatment recommendations, and the delays in picking up prescribed medications that waiting for PA approval can create.

It’s easy to get angry about PAs

Your best response, however, is to practice prudent and—within reason— cost-effective medicine. When generic or insurer-preferred medications are clinically appropriate and meet treatment guidelines, trying them first is sensible and defensible. If your patient fails the initial low-cost treatment, or if a low-cost choice isn’t appropriate, document this clearly and seek approval for a costlier treatment.9

BOTTOM LINE

Physicians have ethical and legal obligations to advocate for their patients’ needs and best interests. This sometimes includes completing prior authorization requests. Find strategies that minimize hassle and make sense in your practice, and seek efficient ways to document the medical necessity of requested tests, procedures, or therapies.

Acknowledgment

Drs. Marett and Mossman thanks Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, and Annette Reynolds, MD, for their helpful input in preparing this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Brown CM, Richards K, Rascati KL, et al. Effects of a psychotherapeutic drug prior authorization (PA) requirement on patients and providers: a providers’ perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(3):181-188.

2. Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB. Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):540-546.

3. Stein BD, Leckman-Westin E, Okeke E, et al. The effects of prior authorization policies on Medicaid-enrolled children’s use of antipsychotic medications: evidence from two Mid-Atlantic states. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):374-381.

4. Adams KT. Prior authorization–still used, still an issue. Biotechnol Healthc. 2010;7(4):28.

5. Garcia MM, Angelini MC, Thomas T, et al. Implementation of an opioid management initiative by a state Medicaid program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(5):447-454.

6. Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, et al. The impact of prior authorization on buprenorphine dose, relapse rates, and cost for Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid dependence [published online July 9, 2014]. Health Serv Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201.

7. Dunn RL, Harrison D, Ripley TL. The beers criteria as an outpatient screening tool for potentially inappropriate medications. Consult Pharm. 2011;26(10):754-763.

8. Lennertz MD, Wertheimer AI. Is prior authorization for prescribed drugs cost-effective? Drug Benefit Trends. 2008;20:136-139.

9. Bendix J. The prior authorization predicament. Med Econ. 2014;91(13)29-30,32,34-35.

10. Farley JF, Cline RR, Schommer JC, et al. Retrospective assessment of Medicaid step-therapy prior authorization policy for atypical antipsychotic medications. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1524-1539; discussion 1506-1507.

11. Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, et al. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(5):247-254.

12. Brown CM, Nwokeji E, Rascati KL, et al. Development of the burden of prior authorization of psychotherapeutics (BoPAP) scale to assess the effects of prior authorization among Texas Medicaid providers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):278-287.

13. Rascati KL, Brown CM. Prior authorization for antipsychotic medications—It’s not just about the money. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1506-1507.

14. Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar disorder. Med Care. 2010;48(1):4-9.

15. Stephens RJ, White SE, Cudnik M, et al. Factors associated with longer lengths of stay for mental health emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2014; 47(4):412-419.

16. Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. Medication continuity among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):878-885.

17. American Medical Association. Opinion 10.01– Fundamental elements of the patient-physician relationship. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/ physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion1001.page?. Accessed October 11, 2014.

18. Hall RC. Ethical and legal implications of managed care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(3):200-208.

19. Porter v Thadani, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35145 (NH 2010).

20. NB ex rel Peacock v District of Columbia, 682 F3d 77 (DC Cir 2012).

21. Wilson v Blue Cross of Southern California, 222 Cal App 3d 660, 271 Cal Rptr 876 (1990).

22. Wickline v State of California, 192 Cal App 3d 1630, 239 Cal Rptr 810 (1986).

23. Terry K. Prior authorization made easier. Med Econ. 2007;84(20):34,38,40.

24. American Medical Association. Ethics Opinion 6.07– Insurance forms completion charges. http://www. ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion607.page? Updated June 1994. Accessed October 11, 2014.

25. Gibson v Medco Health Solutions, 06-CVF-106 (OH 2008).

26. Bendix J. Curing the prior authorization headache. Med Econ. 2013;90(19):24,26-27,29-31.

27. American Medical Association. Electronic prior authorization toolkit. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/advocacy/topics/administrative-simplification-initiatives/electronic-transactions-toolkit/ prior-authorization.page. Accessed October 11, 2014.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Where I practice, most health care plans won’t pay for certain medications without giving prior authorization (PA). Completing PA forms and making telephone calls take up time that could be better spent treating patients. I’m tempted to set a new policy of not doing PAs. If I do, might I face legal trouble?

Submitted by “Dr. A”

If you provide clinical care, you’ve probably dealt with third-party payers who require prior authorization (PA) before they will pay for certain treatments. Dr. A is not alone in feeling exasperated about the time it takes to complete a PA.1 After spending several hours each month waiting on hold and wading through stacks of paperwork, you may feel like Dr. A and consider refusing to do any more PAs.

But is Dr. A’s proposed solution a good idea? To address this question and the frustration that lies behind it, we’ll take a cue from Italian film director Sergio Leone and discuss:

• how PAs affect psychiatric care: the good, the bad, and the ugly

• potential exposure to professional liability and ethics complaints that might result from refusing or failing to seek PA

• strategies to reduce the burden of PAs while providing efficient, effective care.

The good

Recent decades have witnessed huge increases in spending on prescription medication. Psychotropics are no exception; state Medicaid spending for anti-psychotic medication grew from <$1 billion in 1995 to >$5.5 billion in 2005.2

Requiring a PA for expensive drugs is one way that third-party payers try to rein in costs and hold down insurance premiums. Imposing financial constraints often is just one aim of a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) program. Insurers also justify PBMs by pointing out that feedback to practitioners whose prescribing falls well outside the norm—in the form of mailed warnings, physician second opinions, or pharmacist consultation—can improve patient safety and encourage appropriate treatment options for enrolled patients.3,4 Examples of such benefits include reducing overuse of prescription opioids5 and antipsychotics among children,3 misuse of buprenorphine,6 and adverse effects from potentially inappropriate prescriptions.7

The bad

The bad news for doctors: Cost savings for payers come at the expense of providers and their practices, in the form of time spent doing paperwork and talking on the phone to complete PAs or contest PA decisions.8 Addressing PA requests costs an estimated $83,000 per physician per year. The total administrative burden for all 835,000 physicians who practice in the United States therefore is 868,000,000 hours, or $69 billion annually.9

To make matters worse, PA requirements may increase the overall cost of care. After Georgia Medicaid instituted PA requirements for second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), average monthly per member drug costs fell $19.62, but average monthly outpatient treatment costs rose $31.59 per member.10 Pharmacy savings that result from requiring PAs for SGAs can be offset quickly by small increases in the hospitalization rate or emergency department visits.9,11

The ugly

Many physicians believe that the PA process undermines patient care by decreasing time devoted to direct patient contact, incentivizing suboptimal treatment, and limiting medication access.1,12,13 But do any data support this belief? Do PAs impede treatment for vulnerable persons with severe mental illnesses?

The answer, some studies suggest, is “Yes.” A Maine Medicaid PA policy slowed initiation of treatment for bipolar disorder by reducing the rate of starting non-preferred medications, although the same policy had no impact on patients already receiving treatment.14 Another study examined the effect of PA processes for inpatient psychiatry treatment and found that patients were less likely to be admitted on weekends, probably because PA review was not available on those days.15 A third study showed that PA requirements and resulting impediments to getting refills were correlated with medication discontinuation by patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which can increase the risk of decompensation, work-related problems, and hospitalization.16

Problems with PAs

Whether they are helpful or counterproductive, PAs are a practice reality. Dr. A’s proposed solution sounds appealing, but it might create ethical and legal problems.

Among the fundamental elements of ethical medical practice is physicians’ obligation to give patients “guidance … as to the optimal course of action” and to “advocate for patients in dealing with third parties when appropriate.”17 It’s fine for psychiatrists to consider prescribing treatments that patients’ health care coverage favors, but we also have to help patients weigh and evaluate costs, particularly when patients’ circumstances and medical interests militate strongly for options that third-party payers balk at paying for. Patients’ interests—not what’s expedient—are always physicians’ foremost concern.18

Beyond purely ethical considerations, you might face legal consequences if you refuse or fail to seek PAs for what you think is the proper medication. As Table 1 shows, one key factor is whether you are under contract with the patient’s insurance carrier; if you are, failure to seek a PA when appropriate may constitute a breach of the contract (Donna Vanderpool, written communication, October 5, 2014).

If the prescribed medication does not meet the standard of care and your patient suffers some harm, a licensing board complaint and investigation are possible. You also face exposure to a medical malpractice action. Although we do not know of any instances in which such an action has succeeded, 2 recent court decisions suggest that harm to a patient stemmed from failing to seek PA for a medication could constitute grounds for a lawsuit.19,20 Efforts to contain medical costs have been around for decades, and courts have held that physicians, third-party payers, and utilization review intermediaries are bound by “the standard of reasonable community practice”21 and should not let cost limitations “corrupt medical judgment.”22 Physicians who do not appeal limitations at odds with their medical judgment might bear responsibility for any injuries that occur.18,22

Managing PA requests

Given the inevitability of encountering PA requests and your ethical and professional obligations to help patients, what can you do (Table 29,23,27)?

Some practitioners charge patients for time spent completing PAs.23 Although physicians should “complete without charge the appropriate ‘simplified’ insurance claim form as a part of service to the patient;” they also may consider “a charge for more complex or multiple forms … in conformity with local custom.”24 Legally, physicians’ contracts with insurance panels may preclude charging such fees, but if a patient is being seen out of network, the physician does not have a contractual obligation and may charge.9 If your practice setting lets you choose which insurances you accept, the impact and burden of seeking PAs is a factor to consider when deciding whether to participate in a particular panel.23

In an interesting twist, an Ohio physician successfully sued a medical insurance administrator for the cost of his time responding to PA inquiries.25 Reasoning that the insurance administrator “should expect to pay for the reasonable value of” the doctor’s time because the PAs “were solely intended for the benefit of the insurance administrator” or parties whom the administrator served, the judge awarded the doctor $187.50 plus 8% interest.

Considerations that are more practical relate to how to triage and address the volume of PA requests. Some large medical practices centralize PAs and try to set up pre-approved plans of care or blanket approvals for frequently encountered conditions. Centralization also allows one key administrative assistant to develop skills in processing PA requests and to build relationships with payers.26

The administrative assistant also can compile lists of preferred alternative medications, PA forms, and payer Web sites. Using and submitting requests through payer Web sites can speed up PA processing, which saves time and money.27 As electronic health records improve, they may incorporate patients’ formularies and provide automatic alerts for required PAs.23

Patients should be involved, too. They can help to obtain relevant formulary information and to weigh alternative therapies. You can help them understand your role in the PA process, the reasoning behind your treatment recommendations, and the delays in picking up prescribed medications that waiting for PA approval can create.

It’s easy to get angry about PAs

Your best response, however, is to practice prudent and—within reason— cost-effective medicine. When generic or insurer-preferred medications are clinically appropriate and meet treatment guidelines, trying them first is sensible and defensible. If your patient fails the initial low-cost treatment, or if a low-cost choice isn’t appropriate, document this clearly and seek approval for a costlier treatment.9

BOTTOM LINE

Physicians have ethical and legal obligations to advocate for their patients’ needs and best interests. This sometimes includes completing prior authorization requests. Find strategies that minimize hassle and make sense in your practice, and seek efficient ways to document the medical necessity of requested tests, procedures, or therapies.

Acknowledgment

Drs. Marett and Mossman thanks Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, and Annette Reynolds, MD, for their helpful input in preparing this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Where I practice, most health care plans won’t pay for certain medications without giving prior authorization (PA). Completing PA forms and making telephone calls take up time that could be better spent treating patients. I’m tempted to set a new policy of not doing PAs. If I do, might I face legal trouble?

Submitted by “Dr. A”

If you provide clinical care, you’ve probably dealt with third-party payers who require prior authorization (PA) before they will pay for certain treatments. Dr. A is not alone in feeling exasperated about the time it takes to complete a PA.1 After spending several hours each month waiting on hold and wading through stacks of paperwork, you may feel like Dr. A and consider refusing to do any more PAs.

But is Dr. A’s proposed solution a good idea? To address this question and the frustration that lies behind it, we’ll take a cue from Italian film director Sergio Leone and discuss:

• how PAs affect psychiatric care: the good, the bad, and the ugly

• potential exposure to professional liability and ethics complaints that might result from refusing or failing to seek PA

• strategies to reduce the burden of PAs while providing efficient, effective care.

The good

Recent decades have witnessed huge increases in spending on prescription medication. Psychotropics are no exception; state Medicaid spending for anti-psychotic medication grew from <$1 billion in 1995 to >$5.5 billion in 2005.2

Requiring a PA for expensive drugs is one way that third-party payers try to rein in costs and hold down insurance premiums. Imposing financial constraints often is just one aim of a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) program. Insurers also justify PBMs by pointing out that feedback to practitioners whose prescribing falls well outside the norm—in the form of mailed warnings, physician second opinions, or pharmacist consultation—can improve patient safety and encourage appropriate treatment options for enrolled patients.3,4 Examples of such benefits include reducing overuse of prescription opioids5 and antipsychotics among children,3 misuse of buprenorphine,6 and adverse effects from potentially inappropriate prescriptions.7

The bad

The bad news for doctors: Cost savings for payers come at the expense of providers and their practices, in the form of time spent doing paperwork and talking on the phone to complete PAs or contest PA decisions.8 Addressing PA requests costs an estimated $83,000 per physician per year. The total administrative burden for all 835,000 physicians who practice in the United States therefore is 868,000,000 hours, or $69 billion annually.9

To make matters worse, PA requirements may increase the overall cost of care. After Georgia Medicaid instituted PA requirements for second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), average monthly per member drug costs fell $19.62, but average monthly outpatient treatment costs rose $31.59 per member.10 Pharmacy savings that result from requiring PAs for SGAs can be offset quickly by small increases in the hospitalization rate or emergency department visits.9,11

The ugly

Many physicians believe that the PA process undermines patient care by decreasing time devoted to direct patient contact, incentivizing suboptimal treatment, and limiting medication access.1,12,13 But do any data support this belief? Do PAs impede treatment for vulnerable persons with severe mental illnesses?

The answer, some studies suggest, is “Yes.” A Maine Medicaid PA policy slowed initiation of treatment for bipolar disorder by reducing the rate of starting non-preferred medications, although the same policy had no impact on patients already receiving treatment.14 Another study examined the effect of PA processes for inpatient psychiatry treatment and found that patients were less likely to be admitted on weekends, probably because PA review was not available on those days.15 A third study showed that PA requirements and resulting impediments to getting refills were correlated with medication discontinuation by patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which can increase the risk of decompensation, work-related problems, and hospitalization.16

Problems with PAs

Whether they are helpful or counterproductive, PAs are a practice reality. Dr. A’s proposed solution sounds appealing, but it might create ethical and legal problems.

Among the fundamental elements of ethical medical practice is physicians’ obligation to give patients “guidance … as to the optimal course of action” and to “advocate for patients in dealing with third parties when appropriate.”17 It’s fine for psychiatrists to consider prescribing treatments that patients’ health care coverage favors, but we also have to help patients weigh and evaluate costs, particularly when patients’ circumstances and medical interests militate strongly for options that third-party payers balk at paying for. Patients’ interests—not what’s expedient—are always physicians’ foremost concern.18

Beyond purely ethical considerations, you might face legal consequences if you refuse or fail to seek PAs for what you think is the proper medication. As Table 1 shows, one key factor is whether you are under contract with the patient’s insurance carrier; if you are, failure to seek a PA when appropriate may constitute a breach of the contract (Donna Vanderpool, written communication, October 5, 2014).

If the prescribed medication does not meet the standard of care and your patient suffers some harm, a licensing board complaint and investigation are possible. You also face exposure to a medical malpractice action. Although we do not know of any instances in which such an action has succeeded, 2 recent court decisions suggest that harm to a patient stemmed from failing to seek PA for a medication could constitute grounds for a lawsuit.19,20 Efforts to contain medical costs have been around for decades, and courts have held that physicians, third-party payers, and utilization review intermediaries are bound by “the standard of reasonable community practice”21 and should not let cost limitations “corrupt medical judgment.”22 Physicians who do not appeal limitations at odds with their medical judgment might bear responsibility for any injuries that occur.18,22

Managing PA requests

Given the inevitability of encountering PA requests and your ethical and professional obligations to help patients, what can you do (Table 29,23,27)?

Some practitioners charge patients for time spent completing PAs.23 Although physicians should “complete without charge the appropriate ‘simplified’ insurance claim form as a part of service to the patient;” they also may consider “a charge for more complex or multiple forms … in conformity with local custom.”24 Legally, physicians’ contracts with insurance panels may preclude charging such fees, but if a patient is being seen out of network, the physician does not have a contractual obligation and may charge.9 If your practice setting lets you choose which insurances you accept, the impact and burden of seeking PAs is a factor to consider when deciding whether to participate in a particular panel.23

In an interesting twist, an Ohio physician successfully sued a medical insurance administrator for the cost of his time responding to PA inquiries.25 Reasoning that the insurance administrator “should expect to pay for the reasonable value of” the doctor’s time because the PAs “were solely intended for the benefit of the insurance administrator” or parties whom the administrator served, the judge awarded the doctor $187.50 plus 8% interest.

Considerations that are more practical relate to how to triage and address the volume of PA requests. Some large medical practices centralize PAs and try to set up pre-approved plans of care or blanket approvals for frequently encountered conditions. Centralization also allows one key administrative assistant to develop skills in processing PA requests and to build relationships with payers.26

The administrative assistant also can compile lists of preferred alternative medications, PA forms, and payer Web sites. Using and submitting requests through payer Web sites can speed up PA processing, which saves time and money.27 As electronic health records improve, they may incorporate patients’ formularies and provide automatic alerts for required PAs.23

Patients should be involved, too. They can help to obtain relevant formulary information and to weigh alternative therapies. You can help them understand your role in the PA process, the reasoning behind your treatment recommendations, and the delays in picking up prescribed medications that waiting for PA approval can create.

It’s easy to get angry about PAs

Your best response, however, is to practice prudent and—within reason— cost-effective medicine. When generic or insurer-preferred medications are clinically appropriate and meet treatment guidelines, trying them first is sensible and defensible. If your patient fails the initial low-cost treatment, or if a low-cost choice isn’t appropriate, document this clearly and seek approval for a costlier treatment.9

BOTTOM LINE

Physicians have ethical and legal obligations to advocate for their patients’ needs and best interests. This sometimes includes completing prior authorization requests. Find strategies that minimize hassle and make sense in your practice, and seek efficient ways to document the medical necessity of requested tests, procedures, or therapies.

Acknowledgment

Drs. Marett and Mossman thanks Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, and Annette Reynolds, MD, for their helpful input in preparing this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Brown CM, Richards K, Rascati KL, et al. Effects of a psychotherapeutic drug prior authorization (PA) requirement on patients and providers: a providers’ perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(3):181-188.

2. Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB. Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):540-546.

3. Stein BD, Leckman-Westin E, Okeke E, et al. The effects of prior authorization policies on Medicaid-enrolled children’s use of antipsychotic medications: evidence from two Mid-Atlantic states. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):374-381.

4. Adams KT. Prior authorization–still used, still an issue. Biotechnol Healthc. 2010;7(4):28.

5. Garcia MM, Angelini MC, Thomas T, et al. Implementation of an opioid management initiative by a state Medicaid program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(5):447-454.

6. Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, et al. The impact of prior authorization on buprenorphine dose, relapse rates, and cost for Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid dependence [published online July 9, 2014]. Health Serv Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201.

7. Dunn RL, Harrison D, Ripley TL. The beers criteria as an outpatient screening tool for potentially inappropriate medications. Consult Pharm. 2011;26(10):754-763.

8. Lennertz MD, Wertheimer AI. Is prior authorization for prescribed drugs cost-effective? Drug Benefit Trends. 2008;20:136-139.

9. Bendix J. The prior authorization predicament. Med Econ. 2014;91(13)29-30,32,34-35.

10. Farley JF, Cline RR, Schommer JC, et al. Retrospective assessment of Medicaid step-therapy prior authorization policy for atypical antipsychotic medications. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1524-1539; discussion 1506-1507.

11. Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, et al. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(5):247-254.

12. Brown CM, Nwokeji E, Rascati KL, et al. Development of the burden of prior authorization of psychotherapeutics (BoPAP) scale to assess the effects of prior authorization among Texas Medicaid providers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):278-287.

13. Rascati KL, Brown CM. Prior authorization for antipsychotic medications—It’s not just about the money. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1506-1507.

14. Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar disorder. Med Care. 2010;48(1):4-9.

15. Stephens RJ, White SE, Cudnik M, et al. Factors associated with longer lengths of stay for mental health emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2014; 47(4):412-419.

16. Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. Medication continuity among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):878-885.

17. American Medical Association. Opinion 10.01– Fundamental elements of the patient-physician relationship. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/ physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion1001.page?. Accessed October 11, 2014.

18. Hall RC. Ethical and legal implications of managed care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(3):200-208.

19. Porter v Thadani, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35145 (NH 2010).

20. NB ex rel Peacock v District of Columbia, 682 F3d 77 (DC Cir 2012).

21. Wilson v Blue Cross of Southern California, 222 Cal App 3d 660, 271 Cal Rptr 876 (1990).

22. Wickline v State of California, 192 Cal App 3d 1630, 239 Cal Rptr 810 (1986).

23. Terry K. Prior authorization made easier. Med Econ. 2007;84(20):34,38,40.

24. American Medical Association. Ethics Opinion 6.07– Insurance forms completion charges. http://www. ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion607.page? Updated June 1994. Accessed October 11, 2014.

25. Gibson v Medco Health Solutions, 06-CVF-106 (OH 2008).

26. Bendix J. Curing the prior authorization headache. Med Econ. 2013;90(19):24,26-27,29-31.

27. American Medical Association. Electronic prior authorization toolkit. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/advocacy/topics/administrative-simplification-initiatives/electronic-transactions-toolkit/ prior-authorization.page. Accessed October 11, 2014.

1. Brown CM, Richards K, Rascati KL, et al. Effects of a psychotherapeutic drug prior authorization (PA) requirement on patients and providers: a providers’ perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(3):181-188.

2. Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB. Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):540-546.

3. Stein BD, Leckman-Westin E, Okeke E, et al. The effects of prior authorization policies on Medicaid-enrolled children’s use of antipsychotic medications: evidence from two Mid-Atlantic states. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):374-381.

4. Adams KT. Prior authorization–still used, still an issue. Biotechnol Healthc. 2010;7(4):28.

5. Garcia MM, Angelini MC, Thomas T, et al. Implementation of an opioid management initiative by a state Medicaid program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(5):447-454.

6. Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, et al. The impact of prior authorization on buprenorphine dose, relapse rates, and cost for Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid dependence [published online July 9, 2014]. Health Serv Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201.

7. Dunn RL, Harrison D, Ripley TL. The beers criteria as an outpatient screening tool for potentially inappropriate medications. Consult Pharm. 2011;26(10):754-763.

8. Lennertz MD, Wertheimer AI. Is prior authorization for prescribed drugs cost-effective? Drug Benefit Trends. 2008;20:136-139.

9. Bendix J. The prior authorization predicament. Med Econ. 2014;91(13)29-30,32,34-35.

10. Farley JF, Cline RR, Schommer JC, et al. Retrospective assessment of Medicaid step-therapy prior authorization policy for atypical antipsychotic medications. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1524-1539; discussion 1506-1507.

11. Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, et al. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(5):247-254.

12. Brown CM, Nwokeji E, Rascati KL, et al. Development of the burden of prior authorization of psychotherapeutics (BoPAP) scale to assess the effects of prior authorization among Texas Medicaid providers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):278-287.

13. Rascati KL, Brown CM. Prior authorization for antipsychotic medications—It’s not just about the money. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1506-1507.

14. Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar disorder. Med Care. 2010;48(1):4-9.

15. Stephens RJ, White SE, Cudnik M, et al. Factors associated with longer lengths of stay for mental health emergency department patients. J Emerg Med. 2014; 47(4):412-419.

16. Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. Medication continuity among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):878-885.

17. American Medical Association. Opinion 10.01– Fundamental elements of the patient-physician relationship. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/ physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion1001.page?. Accessed October 11, 2014.

18. Hall RC. Ethical and legal implications of managed care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(3):200-208.

19. Porter v Thadani, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35145 (NH 2010).

20. NB ex rel Peacock v District of Columbia, 682 F3d 77 (DC Cir 2012).

21. Wilson v Blue Cross of Southern California, 222 Cal App 3d 660, 271 Cal Rptr 876 (1990).

22. Wickline v State of California, 192 Cal App 3d 1630, 239 Cal Rptr 810 (1986).

23. Terry K. Prior authorization made easier. Med Econ. 2007;84(20):34,38,40.

24. American Medical Association. Ethics Opinion 6.07– Insurance forms completion charges. http://www. ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion607.page? Updated June 1994. Accessed October 11, 2014.

25. Gibson v Medco Health Solutions, 06-CVF-106 (OH 2008).

26. Bendix J. Curing the prior authorization headache. Med Econ. 2013;90(19):24,26-27,29-31.

27. American Medical Association. Electronic prior authorization toolkit. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/advocacy/topics/administrative-simplification-initiatives/electronic-transactions-toolkit/ prior-authorization.page. Accessed October 11, 2014.