User login

Nearly 2.7 million veterans who rely on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for their health care live in rural communities.1 Of these, more than half are aged ≥ 65 years. Rural veterans have greater rates of service-related disability and chronic medical conditions than do their urban counterparts.1,2 Yet because of their rural location, they face unique challenges, including long travel times and distances to health care services, lack of public transportation options, and limited availability of specialized medical and social support services.

Compounding these geographic barriers is a more general lack of workforce infrastructure and a dearth of clinical health care providers (HCPs) skilled in geriatric medicine. The demand for geriatricians is projected to outpace supply and result in a national shortage of nearly 27 000 geriatricians by 2025.3 Moreover, the overwhelming majority (90%) of HCPs identifying as geriatric specialists reside in urban areas.4 This creates tremendous pressure on the health care system to provide remote care for older veterans contending with complex conditions, and ultimately these veterans may not receive the specialized care they need.

Telehealth modalities bridge these gaps by bringing health care to veterans in rural communities. They may also hold promise for strengthening community care in rural areas through workforce development and dissemination of educational resources. The VHA has been recognized as a leader in the field of telehealth since it began offering telehealth services to veterans in 19775-8 and served more than 677 000 Veterans via telehealth in fiscal year (FY) 2015.9 The VHA currently employs multiple modes of telehealth to increase veterans’ access to health care, including: (1) synchronous technology like clinical video telehealth (CVT), which provides live encounters between HCPs and patients using videoconferencing software; and (2) asynchronous technology, such as store-and-forward communication that offers remote transmission and clinical interpretation of veteran health data. The VHA has also strengthened its broad telehealth infrastructure by staffing VHA clinical sites with telehealth clinical technicians and providing telehealth hardware throughout.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) and Office of Rural Health (ORH) established the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers (GRECC) Connect project in 2014 to leverage the existing telehealth technologies at the VA to meet the health care needs of older veterans. GRECC Connect builds on the VHA network of geriatrics expertise in GRECCs by providing telehealth-based consultative support for rural primary care provider (PCP) teams, older veterans, and their families. This program profile describes this project’s mission, structure, and activities.

Program Overview

GRECC Connect leverages the clinical expertise and administrative infrastructure of participating GRECCs in order to reach clinicians and veterans in primarily rural communities.10 GRECCs are VA centers of excellence focused on aging and comprise a large network of interdisciplinary geriatrics expertise. All GRECCs have strong affiliations with local universities and are located in urban VA medical centers (VAMCs). GRECC Connect is based on a hub-and-spoke model in which urban GRECC hub sites are connected to community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) and VAMC spokes that primarily serve veterans in other communities. CBOCs are stand-alone clinics that are geographically separate from a related VA medical center and provide outpatient primary care, mental health care services, and some specialty care services such as cardiology or neurology. They range in size from small, mainly telehealth clinics with 1 technician to large clinics with several specialty providers. Each GRECC hub site partners with an average of 6 CBOCs (range 3-16), each of which is an average distance of 92.8 miles from the related VA medical center (range 20-406 miles).

GRECC Connect was established under the umbrella of the VA Geriatric Scholars Program, which since 2008 integrates geriatrics into rural primary care practices through tailored education for continuing professional development.11 Through intensive courses in geriatrics and quality improvement methods and through participation in local quality improvement projects benefiting older veterans, the Geriatric Scholars Program trains rural PCPs so that they can more effectively and independently diagnose and manage common geriatric syndromes.12 The network of clinician scholars developed by the Geriatric Scholars Program, all rural frontline clinicians at VA clinics, has given the GRECC Connect project a well-prepared, geriatrics-trained workforce to act as project champions at rural CBOCs and VAMCs. The GRECC Connect project’s goals are to enhance access to geriatric specialty care among older veterans with complex medical problems, geriatric syndromes, and increased risk for institutionalization, and to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to rural HCP teams.

Geriatric Provider Consultations

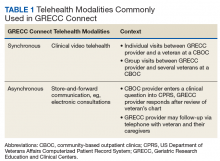

The first overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to improve access to geriatrics specialty care by facilitating linkages between GRECC hub sites and the CBOCs and VAMCs that primarily serve veterans in rural communities. GRECC hub sites offer consultative support from geriatrics specialty team members (eg, geriatricians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, gero- or neuropsychologists, registered nurses [RNs], and social workers) to rural PCP in their catchment area. This support is offered through a variety of telehealth modalities readily available in the VA (Table 1). These include CVT, in which a veteran located at a rural CBOC is seen using videoconferencing software by a geriatrics specialty provider who is located at a GRECC hub site. At some GRECC hub sites, CVT has also been used to conduct group visits between a GRECC provider at the hub site and several veterans who participate from a rural CBOC. Electronic consultations, or e-consults, involve a rural provider entering a clinical question in the VA Computerized Patient Record System. The question is then triaged, and a geriatrics provider at a GRECC responds, based on review of that veteran’s chart. At some GRECC hub sites, the e-consults are more extensive and may include telephone contact with the veteran or their caregiver.

Consultations between GRECC-based teams and rural PCPs may cover any aspect of geriatrics care, ranging from broad concerns to subspecialty areas of geriatric medicine. For instance, general geriatrics consultation may address polypharmacy, during either care transitions or ongoing care. Consultation may also reflect the specific focus area of a particular GRECC, such as cognitive assessment (eg, Pittsburgh GRECC), management of osteoporosis to address falls (eg, Durham GRECC, Miami GRECC), and continence care (eg, Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC).13 Most consultations are initiated by a remote HCP who is seeking geriatrics expertise from the GRECC team.

Some GRECC hub sites, however, employ case finding strategies, or detailed chart reviews, in order to identify older veterans who may benefit from geriatrics consultation. For veterans identified through those mechanisms, the GRECC clinicians suggest that the rural HCP either request or allow an e-consult or evaluation via CVT for those veterans. The geriatric consultations may help identify additional care needs for older veterans and lead to recommendations, orders, or remote provision of a variety of other actions, including VA or non-VA services (eg, home-based primary care, home nursing service, respite service, social support services such as Meals on Wheels); neuropsychological testing; physical or occupational therapy; audiology or optometry referral; falls and fracture risk assessment and interventions to reduce falls (eg, home safety evaluation, physical therapy); osteoporosis risk assessments (eg, densitometry, recommendations for pharmacologic therapy) to reduce the risk of injury or nontraumatic fractures from falls; palliative care for incontinence and hospice; and counseling on geriatric issues such as dementia caregiving, advanced directives, and driving cessation.

More recently, the Miami GRECC has begun evaluating rural veterans at risk for hypoglycemia, providing patient education and counseling about hypoglycemia, and making recommendations to the veterans’ primary care teams.14 Consultations may also lead to the appropriate use or discontinuation of medications, related to polypharmacy. GRECC-based teams, for example, have helped rural HCPs modify medication doses, start appropriate medications for dementia and depression, and identify and stop potentially inappropriate medications (eg, those that increase fall risk or that have significant anticholinergic properties).15

GRECC Connect Geriatric Case Conference Series

The second overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to equip PCPs to better serve their aging veteran patients. This is achieved through twice-monthly, case-based conferences supported by the VA Employee Education System (EES) and delivered through a webinar interface. Case conferences are targeted to members of the health care team who may provide care for rural older adults, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, RNs, psychologists, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, and pharmacists. The format of these sessions includes a clinical case presentation, a didactic portion to enhance knowledge of participants, and an open question/answer period. The conferences focus on discussions of challenging clinical cases, addressing common problems (eg, driving concerns), and the assessment/management of geriatric syndromes (eg, cognitive decline, falls, polypharmacy). These conferences aim to improve the knowledge and skills of rural clinical teams in taking care of older veterans and to disseminate best practices in geriatric medicine, using case discussions to highlight practical applications of practices to clinical care. Recent GRECC Connect geriatric case conferences are listed in Table 2 and are recorded and archived to ensure that busy clinicians may access these trainings at the time of their choosing. These materials are catalogued and archived on the EES server.

Early Experience

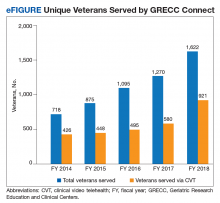

GRECC Connect tracks on an annual basis the number of unique veterans served, number of participating GRECC hub sites and CBOCs, mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites, and number of clinicians and staff engaged in GRECC Connect education programs.16 Since its inception in 2014, the GRECC Connect project has provided direct clinical support to more than 4000 unique veterans (eFigure), of whom half were seen for a cognition-related issue. Consultations were made on behalf of 1,622 veterans in FY 2018, of whom 60% were from rural or highly rural communities and 56.8% were served by CVT visits. The number of GRECC hub sites has increased from 4 in FY 2014 to 12 (of 20 total GRECCs) in FY 2018. The locations of current GRECC hub sites can be found on the Geriatric Scholars website: www.gerischolars.org. Through this expansion, GRECC Connect provides geriatric consultative and educational support to > 70 rural VA clinics in 10 of the 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs).

To assess the reduction in commute times from teleconsultation, we calculated the difference between the mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites (ie, rural clinics) and the mileage from veteran homes to VAMCs where geriatric teams are located. We estimate that the 1622 veterans served in FY 2018 saved a total of 179 121 miles in travel through GRECC Connect. Veterans traveled 106 fewer miles and on average saved $58 in out-of-pocket savings (based on US General Services Administration 2018 standard mileage reimbursement rate of $0.545 per mile). However, many of the veterans have reported anecdotally that the reduction in mileage traveled was less important than the elimination of stress involved in urban navigating, driving, and parking.

More difficult to measure, GRECC Connect seeks to enhance veteran safety by reducing driving distances for older veterans whose driving abilities may be influenced by many age-related health conditions (eg, visual changes, cognitive impairment). For these and other reasons, surveyed veterans overwhelmingly reported that they would be likely to recommend teleconsultation services to other veterans, and that they preferred telemedicine consultation over traveling long distances for in-person clinical consultations.16

Since its inception in 2014, GRECC Connect has provided case-based education to a total of 2335 unique clinicians and staff. Participants have included physicians, nurse practitioners, RNs, social workers, and pharmacists. This distribution reflects the interdisciplinary nature of geriatric care. A plurality of participants (39%) were RNs. Surveyed participants in the GRECC Connect geriatrics case conference series report high overall satisfaction with the learning activity, acquisition of new knowledge and skills, and intention to apply new knowledge and skills to improve job performance.10 In addition, participants agreed that the online training platform was effective for learning and that they would recommend the education series to other HCPs.10,16

Discussion

During its rapid 4-year scale up, GRECC Connect has established a national network and enhanced relationships between GRECC-based clinical teams and rural provider teams. In doing so, the program has begun to improve rural veterans’ access to geriatric specialty care. By providing continuing education to members of the interprofessional health care team, GRECC Connect develops rural providers’ clinical competency and promotes geriatrics skills and expertise. These activities are synergistic: Clinical support enables rural HCPs to become better at managing their own patients, while formal educational activities highlight the availability of specialized consultation available through GRECC Connect. Through ongoing creation of handbooks, workflows, and data analytic strategies, GRECC Connect aims to disseminate this model to additional GRECCs as well as other GEC programs to promote “anywhere to anywhere” VA health care.17

Barriers and Facilitators

GRECC Connect has had notable implementation challenges while new consultation relationships have been forged in order to provide geriatric expertise to rural areas where it is not otherwise available. Many GRECCs had already established connections with rural CBOCs. Among GRECCs that had previously established consultative relationships with rural clinics, the use of telehealth modalities to provide geriatric clinical resources has been a natural extension of these partnerships. GRECCs that lacked these connections, however, often had to obtain buy-in from multiple stakeholders, including rural HCPs and teams, administrative leads, and local telehealth coordinators, and they required VISN- and facility-level leadership to encourage and sustain rural team participation.

Depending on the distance of the GRECC hub-site to the CBOC, efforts to establish and sustain partnerships may require multiple contacts over time (eg, via face-to-face meetings, one-on-one outreach) and large-scale advertising of consultative services. Continuous engagement with CBOC-based teams also involves development of case finding strategies (eg, hospital discharge information, diagnoses, clinical criteria) to better identify veterans who may benefit from GRECC Connect consultation. Owing to the heterogeneity of technological resources, space, scheduling capacity, and staffing at CBOCs, GRECC sites continue to have variable engagement with their CBOC partners.

The inclusion of GRECC Connect within the Geriatric Scholars Program helps ensure that clinician scholars can serve as project champions at their respective rural sites. Rural HCPs with full-time clinical duties initially had difficulty carving out time to participate in GRECC Connect’s case-based conferences. However, the webinar platform has improved and sustained provider participation, and enduring recordings of the presentations allow clinicians to participate in the conferences at their convenience. Finally, the project experienced delays in taking certain administrative steps and hiring staff needed to support the establishment of telehealth modalities—even within a single health care system like the VA, each medical center and regional system has unique policies that complicate how telehealth modalities can be set up.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The GRECC Connect project aims to establish and support meaningful partnerships between urban geriatric specialists and rural HCPs to facilitate veterans’ increased access to geriatric specialty care. VA ORH has recognized it as a Rural Promising Practice, and GRECC Connect is currently being disseminated through an enterprise-wide initiative. Early evidence demonstrates that over 4 years, the expansion of GRECC Connect has helped meet critical aims of improving provider confidence and skills in geriatric management, and of increasing direct service provision. We have also used nationwide education platforms (eg, VA EES) to deliver geriatrics-focused education to health care teams.

Older rural veterans and their caregivers may benefit from this program through decreased travel-associated burden and report high satisfaction with these programs. Through a recently established collaboration with the GEC Data Analysis Center, we will use national data to refine our ability to identify at-risk, older rural veterans and to better evaluate their service needs and the GRECC Connect clinical impact. Because the VA is rapidly expanding use of telehealth and other virtual and digital methods to increase access to care, continued investments in telehealth are central to the VA 5-year strategic plan.18 In this spirit, GRECC Connect will continue to expand its program offerings and to leverage telehealth technologies to meet the needs of older veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Lisa Tenover, MD, PhD, (Palo Alto GRECC) for her contributions to this manuscript; the VA Rural Health Resource Center–Western Region; and GRECC Connect team members for their tireless work to ensure this project’s success. The GRECC Teams include Atlanta/Birmingham (Julia [Annette] Tedford, RN; Marquitta Cox, LMSW; Lisa Welch, LMSW; Mark Phillips; Lanie Walters, PharmD; Kroshona Tabb, PhD; Robert Langford, and Jason [Thomas] Sanders, HT, TCT); Bronx/NY Harbor (Ab Brody, RN; PhD, GNP-BC; Nick Koufacos, LMSW; and Shatice Jones); Canandaigua (Gary Kochersberger, MD; Suzanne Gillespie, MD; Gary Warner, PhD; Christie Hylwa, RPh CCP; Sharon Fell, LMSW; and Dorian Savino, MPA); Durham (Mamata Yanamadala, MBBS; Christy Knight, LCSW, MSW; and Julie Vognsen); Eastern Colorado (Larry Bourg, MD; Skotti Church, MD; Morgan Elmore, DO; Stephanie Hartz, LCSW; Carolyn Horney, MD; Steven Huart, AuD; Kathryn Nearing, PhD; Elizabeth O’Brien, PharmD; Laurence Robbins, MD; Robert Schwartz, MD; Karen Shea, MD; and Joleen Sussman, PhD); Little Rock (Prasad Padala, MD; and Tanya Taylor, RN); Madison (Ryan Bartkus, MD; Timothy Howell, MD; Lindsay Clark, PhD; Lauren Welch, PharmD, BCGP; Ellen Wanninger, MSW, CAPSW; Stacie Monson, RN, BSN; and Teresa Swader, MSW, LCSW); Miami (Carlos Gomez Orozo); New England (Malissa Kraft, PsyD); Palo Alto (Terri Huh, PhD, ABPP; Philip Choe, DO; Dawna Dougherty, LCSW; Ashley Scales, MPH); Pittsburgh (Stacey Shaffer, MD; Carol Dolbee, CRNP; Nancy Kovell, LCSW; Paul Bulgarelli, DO; Lauren Jost, PsyD; and Marcia Homer, RN-BC); and San Antonio (Becky Powers, MD; Che Kelly, RN, BSN; Cynthia Stewart, LCSW; Rebecca Rottman-Sagebiel, PharmD, BCPS, CGP; Melody Moris; Daniel MacCarthy; and Chen-pin Wang, PhD).

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Rural Health Annual report: Thrive 2016. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/ORH2016Thrive508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

2. Holder KA. Veterans in Rural America: 2011–2015. US Census Bureau: Washington, DC; 2016. American Community Survey Reports, ACS-36.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis.2017. National and regional projections of supply and demand for geriatricians: 2013-2025. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/GeriatricsReport51817.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed September 10, 2019.

4. Peterson L, Bazemore A, Bragg E, Xierali I, Warshaw GA. Rural–urban distribution of the U.S. geriatrics physician workforce. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):699-703.

5. Lindeman D. Interview: lessons from a leader in telehealth diffusion: a conversation with Adam Darkins of the Veterans Health Administration. Ageing Int. 2010;36(1):146-154.

6. Darkins A, Foster L, Anderson C, Goldschmidt L, Selvin G. The design, implementation, and operational management of a comprehensive quality management program to support national telehealth networks. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(7):557-564.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Clinical video telehealth into the home (CVTHM)toolkit for providers. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn16//docs/CVTHM_Toolkit.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

8. Darkins A. Telehealth services in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). https://myvitalz.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Telehealth-Services-in-the-United-States.pdf. Published July 2016. Accessed September 10, 2019.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA announces telemental health clinical resource centers during telemedicine association gathering [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/includes/viewPDF.cfm?id=2789. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed September 10, 2019.

10. Hung WW, Rossi M, Thielke S, et al. A multisite geriatric education program for rural providers in the Veteran Health Care System (GRECC Connect). Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2014;35(1):23-40.

11. Kramer BJ. The VA geriatric scholars program. Fed Pract. 2015;32(5):46-48.

12. Kramer BJ, Creekmur B, Howe JL, et al. Veterans Affairs Geriatric Scholars Program: enhancing existing primary care clinician skills in caring for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2343-2348.

13. Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, Edmonds N, Rossi MI. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099.

14. Wright SM, Hedin SC, McConnell M, et al. Using shared decision-making to address possible overtreatment in patients at high risk for hypoglycemia: the Veterans Health Administration’s Choosing Wisely Hypoglycemia Safety Initiative. Clin Diabetes. 2018;36(2):120-127.

15. Chang W, Homer M, Rossi MI. Use of clinical video telehealth as a tool for optimizing medications for rural older veterans with dementia. Geriatrics (Basel). 2018;3(3):pii E44.

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Rural promising practice issue brief: GRECC Connect Project: connecting rural providers with geriatric specialists through telemedicine. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_Promising%20Practice_GRECC_Issue%20Brief.pdf. Published February 2017. Accessed September 10, 2019.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA expands telehealth by allowing health care providers to treat patients across state lines [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4054. Published May 11, 2018. Accessed September 10, 2019.

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2018 – 2024 strategic plan. https://www.va.gov/oei/docs/VA2018-2024strategicPlan.pdf. Updated May 31, 2019. Accessed September 10, 2019.

Nearly 2.7 million veterans who rely on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for their health care live in rural communities.1 Of these, more than half are aged ≥ 65 years. Rural veterans have greater rates of service-related disability and chronic medical conditions than do their urban counterparts.1,2 Yet because of their rural location, they face unique challenges, including long travel times and distances to health care services, lack of public transportation options, and limited availability of specialized medical and social support services.

Compounding these geographic barriers is a more general lack of workforce infrastructure and a dearth of clinical health care providers (HCPs) skilled in geriatric medicine. The demand for geriatricians is projected to outpace supply and result in a national shortage of nearly 27 000 geriatricians by 2025.3 Moreover, the overwhelming majority (90%) of HCPs identifying as geriatric specialists reside in urban areas.4 This creates tremendous pressure on the health care system to provide remote care for older veterans contending with complex conditions, and ultimately these veterans may not receive the specialized care they need.

Telehealth modalities bridge these gaps by bringing health care to veterans in rural communities. They may also hold promise for strengthening community care in rural areas through workforce development and dissemination of educational resources. The VHA has been recognized as a leader in the field of telehealth since it began offering telehealth services to veterans in 19775-8 and served more than 677 000 Veterans via telehealth in fiscal year (FY) 2015.9 The VHA currently employs multiple modes of telehealth to increase veterans’ access to health care, including: (1) synchronous technology like clinical video telehealth (CVT), which provides live encounters between HCPs and patients using videoconferencing software; and (2) asynchronous technology, such as store-and-forward communication that offers remote transmission and clinical interpretation of veteran health data. The VHA has also strengthened its broad telehealth infrastructure by staffing VHA clinical sites with telehealth clinical technicians and providing telehealth hardware throughout.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) and Office of Rural Health (ORH) established the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers (GRECC) Connect project in 2014 to leverage the existing telehealth technologies at the VA to meet the health care needs of older veterans. GRECC Connect builds on the VHA network of geriatrics expertise in GRECCs by providing telehealth-based consultative support for rural primary care provider (PCP) teams, older veterans, and their families. This program profile describes this project’s mission, structure, and activities.

Program Overview

GRECC Connect leverages the clinical expertise and administrative infrastructure of participating GRECCs in order to reach clinicians and veterans in primarily rural communities.10 GRECCs are VA centers of excellence focused on aging and comprise a large network of interdisciplinary geriatrics expertise. All GRECCs have strong affiliations with local universities and are located in urban VA medical centers (VAMCs). GRECC Connect is based on a hub-and-spoke model in which urban GRECC hub sites are connected to community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) and VAMC spokes that primarily serve veterans in other communities. CBOCs are stand-alone clinics that are geographically separate from a related VA medical center and provide outpatient primary care, mental health care services, and some specialty care services such as cardiology or neurology. They range in size from small, mainly telehealth clinics with 1 technician to large clinics with several specialty providers. Each GRECC hub site partners with an average of 6 CBOCs (range 3-16), each of which is an average distance of 92.8 miles from the related VA medical center (range 20-406 miles).

GRECC Connect was established under the umbrella of the VA Geriatric Scholars Program, which since 2008 integrates geriatrics into rural primary care practices through tailored education for continuing professional development.11 Through intensive courses in geriatrics and quality improvement methods and through participation in local quality improvement projects benefiting older veterans, the Geriatric Scholars Program trains rural PCPs so that they can more effectively and independently diagnose and manage common geriatric syndromes.12 The network of clinician scholars developed by the Geriatric Scholars Program, all rural frontline clinicians at VA clinics, has given the GRECC Connect project a well-prepared, geriatrics-trained workforce to act as project champions at rural CBOCs and VAMCs. The GRECC Connect project’s goals are to enhance access to geriatric specialty care among older veterans with complex medical problems, geriatric syndromes, and increased risk for institutionalization, and to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to rural HCP teams.

Geriatric Provider Consultations

The first overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to improve access to geriatrics specialty care by facilitating linkages between GRECC hub sites and the CBOCs and VAMCs that primarily serve veterans in rural communities. GRECC hub sites offer consultative support from geriatrics specialty team members (eg, geriatricians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, gero- or neuropsychologists, registered nurses [RNs], and social workers) to rural PCP in their catchment area. This support is offered through a variety of telehealth modalities readily available in the VA (Table 1). These include CVT, in which a veteran located at a rural CBOC is seen using videoconferencing software by a geriatrics specialty provider who is located at a GRECC hub site. At some GRECC hub sites, CVT has also been used to conduct group visits between a GRECC provider at the hub site and several veterans who participate from a rural CBOC. Electronic consultations, or e-consults, involve a rural provider entering a clinical question in the VA Computerized Patient Record System. The question is then triaged, and a geriatrics provider at a GRECC responds, based on review of that veteran’s chart. At some GRECC hub sites, the e-consults are more extensive and may include telephone contact with the veteran or their caregiver.

Consultations between GRECC-based teams and rural PCPs may cover any aspect of geriatrics care, ranging from broad concerns to subspecialty areas of geriatric medicine. For instance, general geriatrics consultation may address polypharmacy, during either care transitions or ongoing care. Consultation may also reflect the specific focus area of a particular GRECC, such as cognitive assessment (eg, Pittsburgh GRECC), management of osteoporosis to address falls (eg, Durham GRECC, Miami GRECC), and continence care (eg, Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC).13 Most consultations are initiated by a remote HCP who is seeking geriatrics expertise from the GRECC team.

Some GRECC hub sites, however, employ case finding strategies, or detailed chart reviews, in order to identify older veterans who may benefit from geriatrics consultation. For veterans identified through those mechanisms, the GRECC clinicians suggest that the rural HCP either request or allow an e-consult or evaluation via CVT for those veterans. The geriatric consultations may help identify additional care needs for older veterans and lead to recommendations, orders, or remote provision of a variety of other actions, including VA or non-VA services (eg, home-based primary care, home nursing service, respite service, social support services such as Meals on Wheels); neuropsychological testing; physical or occupational therapy; audiology or optometry referral; falls and fracture risk assessment and interventions to reduce falls (eg, home safety evaluation, physical therapy); osteoporosis risk assessments (eg, densitometry, recommendations for pharmacologic therapy) to reduce the risk of injury or nontraumatic fractures from falls; palliative care for incontinence and hospice; and counseling on geriatric issues such as dementia caregiving, advanced directives, and driving cessation.

More recently, the Miami GRECC has begun evaluating rural veterans at risk for hypoglycemia, providing patient education and counseling about hypoglycemia, and making recommendations to the veterans’ primary care teams.14 Consultations may also lead to the appropriate use or discontinuation of medications, related to polypharmacy. GRECC-based teams, for example, have helped rural HCPs modify medication doses, start appropriate medications for dementia and depression, and identify and stop potentially inappropriate medications (eg, those that increase fall risk or that have significant anticholinergic properties).15

GRECC Connect Geriatric Case Conference Series

The second overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to equip PCPs to better serve their aging veteran patients. This is achieved through twice-monthly, case-based conferences supported by the VA Employee Education System (EES) and delivered through a webinar interface. Case conferences are targeted to members of the health care team who may provide care for rural older adults, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, RNs, psychologists, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, and pharmacists. The format of these sessions includes a clinical case presentation, a didactic portion to enhance knowledge of participants, and an open question/answer period. The conferences focus on discussions of challenging clinical cases, addressing common problems (eg, driving concerns), and the assessment/management of geriatric syndromes (eg, cognitive decline, falls, polypharmacy). These conferences aim to improve the knowledge and skills of rural clinical teams in taking care of older veterans and to disseminate best practices in geriatric medicine, using case discussions to highlight practical applications of practices to clinical care. Recent GRECC Connect geriatric case conferences are listed in Table 2 and are recorded and archived to ensure that busy clinicians may access these trainings at the time of their choosing. These materials are catalogued and archived on the EES server.

Early Experience

GRECC Connect tracks on an annual basis the number of unique veterans served, number of participating GRECC hub sites and CBOCs, mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites, and number of clinicians and staff engaged in GRECC Connect education programs.16 Since its inception in 2014, the GRECC Connect project has provided direct clinical support to more than 4000 unique veterans (eFigure), of whom half were seen for a cognition-related issue. Consultations were made on behalf of 1,622 veterans in FY 2018, of whom 60% were from rural or highly rural communities and 56.8% were served by CVT visits. The number of GRECC hub sites has increased from 4 in FY 2014 to 12 (of 20 total GRECCs) in FY 2018. The locations of current GRECC hub sites can be found on the Geriatric Scholars website: www.gerischolars.org. Through this expansion, GRECC Connect provides geriatric consultative and educational support to > 70 rural VA clinics in 10 of the 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs).

To assess the reduction in commute times from teleconsultation, we calculated the difference between the mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites (ie, rural clinics) and the mileage from veteran homes to VAMCs where geriatric teams are located. We estimate that the 1622 veterans served in FY 2018 saved a total of 179 121 miles in travel through GRECC Connect. Veterans traveled 106 fewer miles and on average saved $58 in out-of-pocket savings (based on US General Services Administration 2018 standard mileage reimbursement rate of $0.545 per mile). However, many of the veterans have reported anecdotally that the reduction in mileage traveled was less important than the elimination of stress involved in urban navigating, driving, and parking.

More difficult to measure, GRECC Connect seeks to enhance veteran safety by reducing driving distances for older veterans whose driving abilities may be influenced by many age-related health conditions (eg, visual changes, cognitive impairment). For these and other reasons, surveyed veterans overwhelmingly reported that they would be likely to recommend teleconsultation services to other veterans, and that they preferred telemedicine consultation over traveling long distances for in-person clinical consultations.16

Since its inception in 2014, GRECC Connect has provided case-based education to a total of 2335 unique clinicians and staff. Participants have included physicians, nurse practitioners, RNs, social workers, and pharmacists. This distribution reflects the interdisciplinary nature of geriatric care. A plurality of participants (39%) were RNs. Surveyed participants in the GRECC Connect geriatrics case conference series report high overall satisfaction with the learning activity, acquisition of new knowledge and skills, and intention to apply new knowledge and skills to improve job performance.10 In addition, participants agreed that the online training platform was effective for learning and that they would recommend the education series to other HCPs.10,16

Discussion

During its rapid 4-year scale up, GRECC Connect has established a national network and enhanced relationships between GRECC-based clinical teams and rural provider teams. In doing so, the program has begun to improve rural veterans’ access to geriatric specialty care. By providing continuing education to members of the interprofessional health care team, GRECC Connect develops rural providers’ clinical competency and promotes geriatrics skills and expertise. These activities are synergistic: Clinical support enables rural HCPs to become better at managing their own patients, while formal educational activities highlight the availability of specialized consultation available through GRECC Connect. Through ongoing creation of handbooks, workflows, and data analytic strategies, GRECC Connect aims to disseminate this model to additional GRECCs as well as other GEC programs to promote “anywhere to anywhere” VA health care.17

Barriers and Facilitators

GRECC Connect has had notable implementation challenges while new consultation relationships have been forged in order to provide geriatric expertise to rural areas where it is not otherwise available. Many GRECCs had already established connections with rural CBOCs. Among GRECCs that had previously established consultative relationships with rural clinics, the use of telehealth modalities to provide geriatric clinical resources has been a natural extension of these partnerships. GRECCs that lacked these connections, however, often had to obtain buy-in from multiple stakeholders, including rural HCPs and teams, administrative leads, and local telehealth coordinators, and they required VISN- and facility-level leadership to encourage and sustain rural team participation.

Depending on the distance of the GRECC hub-site to the CBOC, efforts to establish and sustain partnerships may require multiple contacts over time (eg, via face-to-face meetings, one-on-one outreach) and large-scale advertising of consultative services. Continuous engagement with CBOC-based teams also involves development of case finding strategies (eg, hospital discharge information, diagnoses, clinical criteria) to better identify veterans who may benefit from GRECC Connect consultation. Owing to the heterogeneity of technological resources, space, scheduling capacity, and staffing at CBOCs, GRECC sites continue to have variable engagement with their CBOC partners.

The inclusion of GRECC Connect within the Geriatric Scholars Program helps ensure that clinician scholars can serve as project champions at their respective rural sites. Rural HCPs with full-time clinical duties initially had difficulty carving out time to participate in GRECC Connect’s case-based conferences. However, the webinar platform has improved and sustained provider participation, and enduring recordings of the presentations allow clinicians to participate in the conferences at their convenience. Finally, the project experienced delays in taking certain administrative steps and hiring staff needed to support the establishment of telehealth modalities—even within a single health care system like the VA, each medical center and regional system has unique policies that complicate how telehealth modalities can be set up.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The GRECC Connect project aims to establish and support meaningful partnerships between urban geriatric specialists and rural HCPs to facilitate veterans’ increased access to geriatric specialty care. VA ORH has recognized it as a Rural Promising Practice, and GRECC Connect is currently being disseminated through an enterprise-wide initiative. Early evidence demonstrates that over 4 years, the expansion of GRECC Connect has helped meet critical aims of improving provider confidence and skills in geriatric management, and of increasing direct service provision. We have also used nationwide education platforms (eg, VA EES) to deliver geriatrics-focused education to health care teams.

Older rural veterans and their caregivers may benefit from this program through decreased travel-associated burden and report high satisfaction with these programs. Through a recently established collaboration with the GEC Data Analysis Center, we will use national data to refine our ability to identify at-risk, older rural veterans and to better evaluate their service needs and the GRECC Connect clinical impact. Because the VA is rapidly expanding use of telehealth and other virtual and digital methods to increase access to care, continued investments in telehealth are central to the VA 5-year strategic plan.18 In this spirit, GRECC Connect will continue to expand its program offerings and to leverage telehealth technologies to meet the needs of older veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Lisa Tenover, MD, PhD, (Palo Alto GRECC) for her contributions to this manuscript; the VA Rural Health Resource Center–Western Region; and GRECC Connect team members for their tireless work to ensure this project’s success. The GRECC Teams include Atlanta/Birmingham (Julia [Annette] Tedford, RN; Marquitta Cox, LMSW; Lisa Welch, LMSW; Mark Phillips; Lanie Walters, PharmD; Kroshona Tabb, PhD; Robert Langford, and Jason [Thomas] Sanders, HT, TCT); Bronx/NY Harbor (Ab Brody, RN; PhD, GNP-BC; Nick Koufacos, LMSW; and Shatice Jones); Canandaigua (Gary Kochersberger, MD; Suzanne Gillespie, MD; Gary Warner, PhD; Christie Hylwa, RPh CCP; Sharon Fell, LMSW; and Dorian Savino, MPA); Durham (Mamata Yanamadala, MBBS; Christy Knight, LCSW, MSW; and Julie Vognsen); Eastern Colorado (Larry Bourg, MD; Skotti Church, MD; Morgan Elmore, DO; Stephanie Hartz, LCSW; Carolyn Horney, MD; Steven Huart, AuD; Kathryn Nearing, PhD; Elizabeth O’Brien, PharmD; Laurence Robbins, MD; Robert Schwartz, MD; Karen Shea, MD; and Joleen Sussman, PhD); Little Rock (Prasad Padala, MD; and Tanya Taylor, RN); Madison (Ryan Bartkus, MD; Timothy Howell, MD; Lindsay Clark, PhD; Lauren Welch, PharmD, BCGP; Ellen Wanninger, MSW, CAPSW; Stacie Monson, RN, BSN; and Teresa Swader, MSW, LCSW); Miami (Carlos Gomez Orozo); New England (Malissa Kraft, PsyD); Palo Alto (Terri Huh, PhD, ABPP; Philip Choe, DO; Dawna Dougherty, LCSW; Ashley Scales, MPH); Pittsburgh (Stacey Shaffer, MD; Carol Dolbee, CRNP; Nancy Kovell, LCSW; Paul Bulgarelli, DO; Lauren Jost, PsyD; and Marcia Homer, RN-BC); and San Antonio (Becky Powers, MD; Che Kelly, RN, BSN; Cynthia Stewart, LCSW; Rebecca Rottman-Sagebiel, PharmD, BCPS, CGP; Melody Moris; Daniel MacCarthy; and Chen-pin Wang, PhD).

Nearly 2.7 million veterans who rely on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for their health care live in rural communities.1 Of these, more than half are aged ≥ 65 years. Rural veterans have greater rates of service-related disability and chronic medical conditions than do their urban counterparts.1,2 Yet because of their rural location, they face unique challenges, including long travel times and distances to health care services, lack of public transportation options, and limited availability of specialized medical and social support services.

Compounding these geographic barriers is a more general lack of workforce infrastructure and a dearth of clinical health care providers (HCPs) skilled in geriatric medicine. The demand for geriatricians is projected to outpace supply and result in a national shortage of nearly 27 000 geriatricians by 2025.3 Moreover, the overwhelming majority (90%) of HCPs identifying as geriatric specialists reside in urban areas.4 This creates tremendous pressure on the health care system to provide remote care for older veterans contending with complex conditions, and ultimately these veterans may not receive the specialized care they need.

Telehealth modalities bridge these gaps by bringing health care to veterans in rural communities. They may also hold promise for strengthening community care in rural areas through workforce development and dissemination of educational resources. The VHA has been recognized as a leader in the field of telehealth since it began offering telehealth services to veterans in 19775-8 and served more than 677 000 Veterans via telehealth in fiscal year (FY) 2015.9 The VHA currently employs multiple modes of telehealth to increase veterans’ access to health care, including: (1) synchronous technology like clinical video telehealth (CVT), which provides live encounters between HCPs and patients using videoconferencing software; and (2) asynchronous technology, such as store-and-forward communication that offers remote transmission and clinical interpretation of veteran health data. The VHA has also strengthened its broad telehealth infrastructure by staffing VHA clinical sites with telehealth clinical technicians and providing telehealth hardware throughout.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) and Office of Rural Health (ORH) established the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers (GRECC) Connect project in 2014 to leverage the existing telehealth technologies at the VA to meet the health care needs of older veterans. GRECC Connect builds on the VHA network of geriatrics expertise in GRECCs by providing telehealth-based consultative support for rural primary care provider (PCP) teams, older veterans, and their families. This program profile describes this project’s mission, structure, and activities.

Program Overview

GRECC Connect leverages the clinical expertise and administrative infrastructure of participating GRECCs in order to reach clinicians and veterans in primarily rural communities.10 GRECCs are VA centers of excellence focused on aging and comprise a large network of interdisciplinary geriatrics expertise. All GRECCs have strong affiliations with local universities and are located in urban VA medical centers (VAMCs). GRECC Connect is based on a hub-and-spoke model in which urban GRECC hub sites are connected to community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) and VAMC spokes that primarily serve veterans in other communities. CBOCs are stand-alone clinics that are geographically separate from a related VA medical center and provide outpatient primary care, mental health care services, and some specialty care services such as cardiology or neurology. They range in size from small, mainly telehealth clinics with 1 technician to large clinics with several specialty providers. Each GRECC hub site partners with an average of 6 CBOCs (range 3-16), each of which is an average distance of 92.8 miles from the related VA medical center (range 20-406 miles).

GRECC Connect was established under the umbrella of the VA Geriatric Scholars Program, which since 2008 integrates geriatrics into rural primary care practices through tailored education for continuing professional development.11 Through intensive courses in geriatrics and quality improvement methods and through participation in local quality improvement projects benefiting older veterans, the Geriatric Scholars Program trains rural PCPs so that they can more effectively and independently diagnose and manage common geriatric syndromes.12 The network of clinician scholars developed by the Geriatric Scholars Program, all rural frontline clinicians at VA clinics, has given the GRECC Connect project a well-prepared, geriatrics-trained workforce to act as project champions at rural CBOCs and VAMCs. The GRECC Connect project’s goals are to enhance access to geriatric specialty care among older veterans with complex medical problems, geriatric syndromes, and increased risk for institutionalization, and to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to rural HCP teams.

Geriatric Provider Consultations

The first overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to improve access to geriatrics specialty care by facilitating linkages between GRECC hub sites and the CBOCs and VAMCs that primarily serve veterans in rural communities. GRECC hub sites offer consultative support from geriatrics specialty team members (eg, geriatricians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, gero- or neuropsychologists, registered nurses [RNs], and social workers) to rural PCP in their catchment area. This support is offered through a variety of telehealth modalities readily available in the VA (Table 1). These include CVT, in which a veteran located at a rural CBOC is seen using videoconferencing software by a geriatrics specialty provider who is located at a GRECC hub site. At some GRECC hub sites, CVT has also been used to conduct group visits between a GRECC provider at the hub site and several veterans who participate from a rural CBOC. Electronic consultations, or e-consults, involve a rural provider entering a clinical question in the VA Computerized Patient Record System. The question is then triaged, and a geriatrics provider at a GRECC responds, based on review of that veteran’s chart. At some GRECC hub sites, the e-consults are more extensive and may include telephone contact with the veteran or their caregiver.

Consultations between GRECC-based teams and rural PCPs may cover any aspect of geriatrics care, ranging from broad concerns to subspecialty areas of geriatric medicine. For instance, general geriatrics consultation may address polypharmacy, during either care transitions or ongoing care. Consultation may also reflect the specific focus area of a particular GRECC, such as cognitive assessment (eg, Pittsburgh GRECC), management of osteoporosis to address falls (eg, Durham GRECC, Miami GRECC), and continence care (eg, Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC).13 Most consultations are initiated by a remote HCP who is seeking geriatrics expertise from the GRECC team.

Some GRECC hub sites, however, employ case finding strategies, or detailed chart reviews, in order to identify older veterans who may benefit from geriatrics consultation. For veterans identified through those mechanisms, the GRECC clinicians suggest that the rural HCP either request or allow an e-consult or evaluation via CVT for those veterans. The geriatric consultations may help identify additional care needs for older veterans and lead to recommendations, orders, or remote provision of a variety of other actions, including VA or non-VA services (eg, home-based primary care, home nursing service, respite service, social support services such as Meals on Wheels); neuropsychological testing; physical or occupational therapy; audiology or optometry referral; falls and fracture risk assessment and interventions to reduce falls (eg, home safety evaluation, physical therapy); osteoporosis risk assessments (eg, densitometry, recommendations for pharmacologic therapy) to reduce the risk of injury or nontraumatic fractures from falls; palliative care for incontinence and hospice; and counseling on geriatric issues such as dementia caregiving, advanced directives, and driving cessation.

More recently, the Miami GRECC has begun evaluating rural veterans at risk for hypoglycemia, providing patient education and counseling about hypoglycemia, and making recommendations to the veterans’ primary care teams.14 Consultations may also lead to the appropriate use or discontinuation of medications, related to polypharmacy. GRECC-based teams, for example, have helped rural HCPs modify medication doses, start appropriate medications for dementia and depression, and identify and stop potentially inappropriate medications (eg, those that increase fall risk or that have significant anticholinergic properties).15

GRECC Connect Geriatric Case Conference Series

The second overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to equip PCPs to better serve their aging veteran patients. This is achieved through twice-monthly, case-based conferences supported by the VA Employee Education System (EES) and delivered through a webinar interface. Case conferences are targeted to members of the health care team who may provide care for rural older adults, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, RNs, psychologists, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, and pharmacists. The format of these sessions includes a clinical case presentation, a didactic portion to enhance knowledge of participants, and an open question/answer period. The conferences focus on discussions of challenging clinical cases, addressing common problems (eg, driving concerns), and the assessment/management of geriatric syndromes (eg, cognitive decline, falls, polypharmacy). These conferences aim to improve the knowledge and skills of rural clinical teams in taking care of older veterans and to disseminate best practices in geriatric medicine, using case discussions to highlight practical applications of practices to clinical care. Recent GRECC Connect geriatric case conferences are listed in Table 2 and are recorded and archived to ensure that busy clinicians may access these trainings at the time of their choosing. These materials are catalogued and archived on the EES server.

Early Experience

GRECC Connect tracks on an annual basis the number of unique veterans served, number of participating GRECC hub sites and CBOCs, mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites, and number of clinicians and staff engaged in GRECC Connect education programs.16 Since its inception in 2014, the GRECC Connect project has provided direct clinical support to more than 4000 unique veterans (eFigure), of whom half were seen for a cognition-related issue. Consultations were made on behalf of 1,622 veterans in FY 2018, of whom 60% were from rural or highly rural communities and 56.8% were served by CVT visits. The number of GRECC hub sites has increased from 4 in FY 2014 to 12 (of 20 total GRECCs) in FY 2018. The locations of current GRECC hub sites can be found on the Geriatric Scholars website: www.gerischolars.org. Through this expansion, GRECC Connect provides geriatric consultative and educational support to > 70 rural VA clinics in 10 of the 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs).

To assess the reduction in commute times from teleconsultation, we calculated the difference between the mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites (ie, rural clinics) and the mileage from veteran homes to VAMCs where geriatric teams are located. We estimate that the 1622 veterans served in FY 2018 saved a total of 179 121 miles in travel through GRECC Connect. Veterans traveled 106 fewer miles and on average saved $58 in out-of-pocket savings (based on US General Services Administration 2018 standard mileage reimbursement rate of $0.545 per mile). However, many of the veterans have reported anecdotally that the reduction in mileage traveled was less important than the elimination of stress involved in urban navigating, driving, and parking.

More difficult to measure, GRECC Connect seeks to enhance veteran safety by reducing driving distances for older veterans whose driving abilities may be influenced by many age-related health conditions (eg, visual changes, cognitive impairment). For these and other reasons, surveyed veterans overwhelmingly reported that they would be likely to recommend teleconsultation services to other veterans, and that they preferred telemedicine consultation over traveling long distances for in-person clinical consultations.16

Since its inception in 2014, GRECC Connect has provided case-based education to a total of 2335 unique clinicians and staff. Participants have included physicians, nurse practitioners, RNs, social workers, and pharmacists. This distribution reflects the interdisciplinary nature of geriatric care. A plurality of participants (39%) were RNs. Surveyed participants in the GRECC Connect geriatrics case conference series report high overall satisfaction with the learning activity, acquisition of new knowledge and skills, and intention to apply new knowledge and skills to improve job performance.10 In addition, participants agreed that the online training platform was effective for learning and that they would recommend the education series to other HCPs.10,16

Discussion

During its rapid 4-year scale up, GRECC Connect has established a national network and enhanced relationships between GRECC-based clinical teams and rural provider teams. In doing so, the program has begun to improve rural veterans’ access to geriatric specialty care. By providing continuing education to members of the interprofessional health care team, GRECC Connect develops rural providers’ clinical competency and promotes geriatrics skills and expertise. These activities are synergistic: Clinical support enables rural HCPs to become better at managing their own patients, while formal educational activities highlight the availability of specialized consultation available through GRECC Connect. Through ongoing creation of handbooks, workflows, and data analytic strategies, GRECC Connect aims to disseminate this model to additional GRECCs as well as other GEC programs to promote “anywhere to anywhere” VA health care.17

Barriers and Facilitators

GRECC Connect has had notable implementation challenges while new consultation relationships have been forged in order to provide geriatric expertise to rural areas where it is not otherwise available. Many GRECCs had already established connections with rural CBOCs. Among GRECCs that had previously established consultative relationships with rural clinics, the use of telehealth modalities to provide geriatric clinical resources has been a natural extension of these partnerships. GRECCs that lacked these connections, however, often had to obtain buy-in from multiple stakeholders, including rural HCPs and teams, administrative leads, and local telehealth coordinators, and they required VISN- and facility-level leadership to encourage and sustain rural team participation.

Depending on the distance of the GRECC hub-site to the CBOC, efforts to establish and sustain partnerships may require multiple contacts over time (eg, via face-to-face meetings, one-on-one outreach) and large-scale advertising of consultative services. Continuous engagement with CBOC-based teams also involves development of case finding strategies (eg, hospital discharge information, diagnoses, clinical criteria) to better identify veterans who may benefit from GRECC Connect consultation. Owing to the heterogeneity of technological resources, space, scheduling capacity, and staffing at CBOCs, GRECC sites continue to have variable engagement with their CBOC partners.

The inclusion of GRECC Connect within the Geriatric Scholars Program helps ensure that clinician scholars can serve as project champions at their respective rural sites. Rural HCPs with full-time clinical duties initially had difficulty carving out time to participate in GRECC Connect’s case-based conferences. However, the webinar platform has improved and sustained provider participation, and enduring recordings of the presentations allow clinicians to participate in the conferences at their convenience. Finally, the project experienced delays in taking certain administrative steps and hiring staff needed to support the establishment of telehealth modalities—even within a single health care system like the VA, each medical center and regional system has unique policies that complicate how telehealth modalities can be set up.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The GRECC Connect project aims to establish and support meaningful partnerships between urban geriatric specialists and rural HCPs to facilitate veterans’ increased access to geriatric specialty care. VA ORH has recognized it as a Rural Promising Practice, and GRECC Connect is currently being disseminated through an enterprise-wide initiative. Early evidence demonstrates that over 4 years, the expansion of GRECC Connect has helped meet critical aims of improving provider confidence and skills in geriatric management, and of increasing direct service provision. We have also used nationwide education platforms (eg, VA EES) to deliver geriatrics-focused education to health care teams.

Older rural veterans and their caregivers may benefit from this program through decreased travel-associated burden and report high satisfaction with these programs. Through a recently established collaboration with the GEC Data Analysis Center, we will use national data to refine our ability to identify at-risk, older rural veterans and to better evaluate their service needs and the GRECC Connect clinical impact. Because the VA is rapidly expanding use of telehealth and other virtual and digital methods to increase access to care, continued investments in telehealth are central to the VA 5-year strategic plan.18 In this spirit, GRECC Connect will continue to expand its program offerings and to leverage telehealth technologies to meet the needs of older veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Lisa Tenover, MD, PhD, (Palo Alto GRECC) for her contributions to this manuscript; the VA Rural Health Resource Center–Western Region; and GRECC Connect team members for their tireless work to ensure this project’s success. The GRECC Teams include Atlanta/Birmingham (Julia [Annette] Tedford, RN; Marquitta Cox, LMSW; Lisa Welch, LMSW; Mark Phillips; Lanie Walters, PharmD; Kroshona Tabb, PhD; Robert Langford, and Jason [Thomas] Sanders, HT, TCT); Bronx/NY Harbor (Ab Brody, RN; PhD, GNP-BC; Nick Koufacos, LMSW; and Shatice Jones); Canandaigua (Gary Kochersberger, MD; Suzanne Gillespie, MD; Gary Warner, PhD; Christie Hylwa, RPh CCP; Sharon Fell, LMSW; and Dorian Savino, MPA); Durham (Mamata Yanamadala, MBBS; Christy Knight, LCSW, MSW; and Julie Vognsen); Eastern Colorado (Larry Bourg, MD; Skotti Church, MD; Morgan Elmore, DO; Stephanie Hartz, LCSW; Carolyn Horney, MD; Steven Huart, AuD; Kathryn Nearing, PhD; Elizabeth O’Brien, PharmD; Laurence Robbins, MD; Robert Schwartz, MD; Karen Shea, MD; and Joleen Sussman, PhD); Little Rock (Prasad Padala, MD; and Tanya Taylor, RN); Madison (Ryan Bartkus, MD; Timothy Howell, MD; Lindsay Clark, PhD; Lauren Welch, PharmD, BCGP; Ellen Wanninger, MSW, CAPSW; Stacie Monson, RN, BSN; and Teresa Swader, MSW, LCSW); Miami (Carlos Gomez Orozo); New England (Malissa Kraft, PsyD); Palo Alto (Terri Huh, PhD, ABPP; Philip Choe, DO; Dawna Dougherty, LCSW; Ashley Scales, MPH); Pittsburgh (Stacey Shaffer, MD; Carol Dolbee, CRNP; Nancy Kovell, LCSW; Paul Bulgarelli, DO; Lauren Jost, PsyD; and Marcia Homer, RN-BC); and San Antonio (Becky Powers, MD; Che Kelly, RN, BSN; Cynthia Stewart, LCSW; Rebecca Rottman-Sagebiel, PharmD, BCPS, CGP; Melody Moris; Daniel MacCarthy; and Chen-pin Wang, PhD).

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Rural Health Annual report: Thrive 2016. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/ORH2016Thrive508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

2. Holder KA. Veterans in Rural America: 2011–2015. US Census Bureau: Washington, DC; 2016. American Community Survey Reports, ACS-36.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis.2017. National and regional projections of supply and demand for geriatricians: 2013-2025. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/GeriatricsReport51817.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed September 10, 2019.

4. Peterson L, Bazemore A, Bragg E, Xierali I, Warshaw GA. Rural–urban distribution of the U.S. geriatrics physician workforce. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):699-703.

5. Lindeman D. Interview: lessons from a leader in telehealth diffusion: a conversation with Adam Darkins of the Veterans Health Administration. Ageing Int. 2010;36(1):146-154.

6. Darkins A, Foster L, Anderson C, Goldschmidt L, Selvin G. The design, implementation, and operational management of a comprehensive quality management program to support national telehealth networks. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(7):557-564.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Clinical video telehealth into the home (CVTHM)toolkit for providers. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn16//docs/CVTHM_Toolkit.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

8. Darkins A. Telehealth services in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). https://myvitalz.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Telehealth-Services-in-the-United-States.pdf. Published July 2016. Accessed September 10, 2019.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA announces telemental health clinical resource centers during telemedicine association gathering [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/includes/viewPDF.cfm?id=2789. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed September 10, 2019.

10. Hung WW, Rossi M, Thielke S, et al. A multisite geriatric education program for rural providers in the Veteran Health Care System (GRECC Connect). Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2014;35(1):23-40.

11. Kramer BJ. The VA geriatric scholars program. Fed Pract. 2015;32(5):46-48.

12. Kramer BJ, Creekmur B, Howe JL, et al. Veterans Affairs Geriatric Scholars Program: enhancing existing primary care clinician skills in caring for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2343-2348.

13. Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, Edmonds N, Rossi MI. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099.

14. Wright SM, Hedin SC, McConnell M, et al. Using shared decision-making to address possible overtreatment in patients at high risk for hypoglycemia: the Veterans Health Administration’s Choosing Wisely Hypoglycemia Safety Initiative. Clin Diabetes. 2018;36(2):120-127.

15. Chang W, Homer M, Rossi MI. Use of clinical video telehealth as a tool for optimizing medications for rural older veterans with dementia. Geriatrics (Basel). 2018;3(3):pii E44.

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Rural promising practice issue brief: GRECC Connect Project: connecting rural providers with geriatric specialists through telemedicine. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_Promising%20Practice_GRECC_Issue%20Brief.pdf. Published February 2017. Accessed September 10, 2019.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA expands telehealth by allowing health care providers to treat patients across state lines [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4054. Published May 11, 2018. Accessed September 10, 2019.

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2018 – 2024 strategic plan. https://www.va.gov/oei/docs/VA2018-2024strategicPlan.pdf. Updated May 31, 2019. Accessed September 10, 2019.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Rural Health Annual report: Thrive 2016. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/ORH2016Thrive508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

2. Holder KA. Veterans in Rural America: 2011–2015. US Census Bureau: Washington, DC; 2016. American Community Survey Reports, ACS-36.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis.2017. National and regional projections of supply and demand for geriatricians: 2013-2025. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/GeriatricsReport51817.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed September 10, 2019.

4. Peterson L, Bazemore A, Bragg E, Xierali I, Warshaw GA. Rural–urban distribution of the U.S. geriatrics physician workforce. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):699-703.

5. Lindeman D. Interview: lessons from a leader in telehealth diffusion: a conversation with Adam Darkins of the Veterans Health Administration. Ageing Int. 2010;36(1):146-154.

6. Darkins A, Foster L, Anderson C, Goldschmidt L, Selvin G. The design, implementation, and operational management of a comprehensive quality management program to support national telehealth networks. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(7):557-564.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Clinical video telehealth into the home (CVTHM)toolkit for providers. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn16//docs/CVTHM_Toolkit.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

8. Darkins A. Telehealth services in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). https://myvitalz.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Telehealth-Services-in-the-United-States.pdf. Published July 2016. Accessed September 10, 2019.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA announces telemental health clinical resource centers during telemedicine association gathering [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/includes/viewPDF.cfm?id=2789. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed September 10, 2019.

10. Hung WW, Rossi M, Thielke S, et al. A multisite geriatric education program for rural providers in the Veteran Health Care System (GRECC Connect). Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2014;35(1):23-40.

11. Kramer BJ. The VA geriatric scholars program. Fed Pract. 2015;32(5):46-48.

12. Kramer BJ, Creekmur B, Howe JL, et al. Veterans Affairs Geriatric Scholars Program: enhancing existing primary care clinician skills in caring for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2343-2348.

13. Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, Edmonds N, Rossi MI. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099.

14. Wright SM, Hedin SC, McConnell M, et al. Using shared decision-making to address possible overtreatment in patients at high risk for hypoglycemia: the Veterans Health Administration’s Choosing Wisely Hypoglycemia Safety Initiative. Clin Diabetes. 2018;36(2):120-127.

15. Chang W, Homer M, Rossi MI. Use of clinical video telehealth as a tool for optimizing medications for rural older veterans with dementia. Geriatrics (Basel). 2018;3(3):pii E44.

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Rural promising practice issue brief: GRECC Connect Project: connecting rural providers with geriatric specialists through telemedicine. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_Promising%20Practice_GRECC_Issue%20Brief.pdf. Published February 2017. Accessed September 10, 2019.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA expands telehealth by allowing health care providers to treat patients across state lines [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4054. Published May 11, 2018. Accessed September 10, 2019.

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2018 – 2024 strategic plan. https://www.va.gov/oei/docs/VA2018-2024strategicPlan.pdf. Updated May 31, 2019. Accessed September 10, 2019.