User login

Aging equipment, valuable data, and an improperly trained workforce make health care IT extraordinarily vulnerable to external malfeasance, as demonstrated by the WannaCry virus episode that occurred this spring in the United Kingdom.

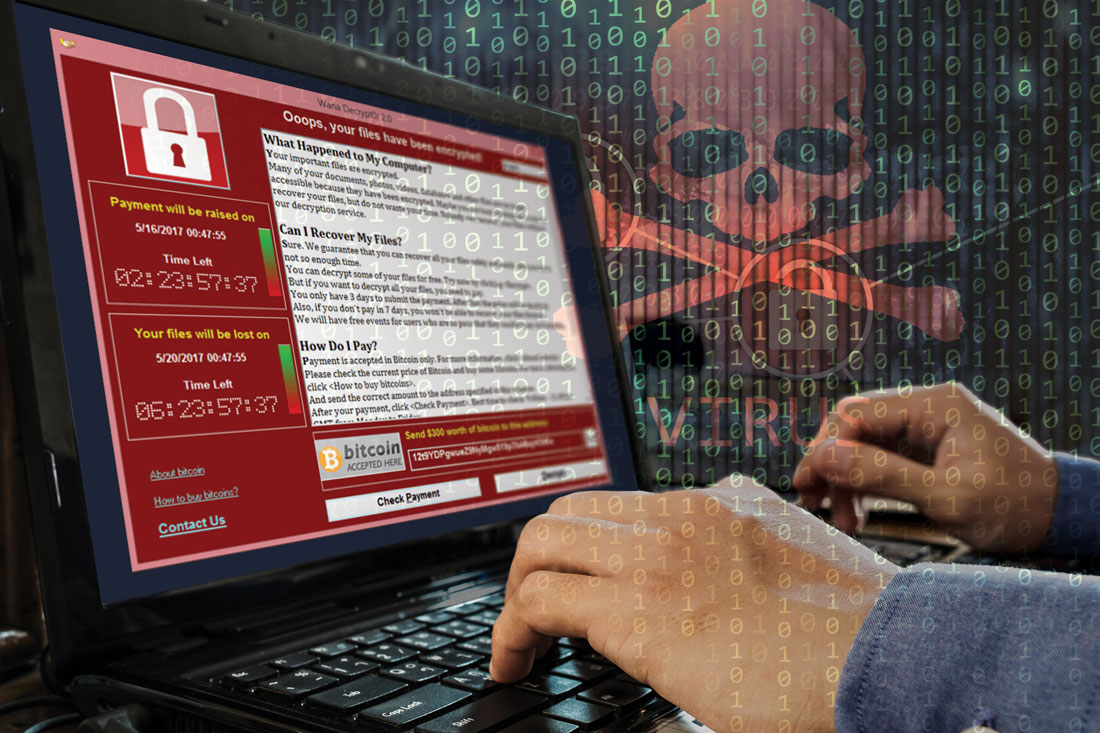

Computer hackers used a weakness in the operating system employed by the U.K. National Health Service, allowing the WannaCry virus to spread quickly across connected systems. The ransomware attack locked clinicians out of patient records and diagnostic machines that were connected, bringing patient care to a near standstill.

The attack lasted 3 days until Marcus Hutchins, a 22-year-old security researcher, stumbled onto a way to slow the spread of the virus enough to manage it, but not before nearly 60 million attacks had been conducted, Salim Neino, CEO of Kryptos Logic, testified June 15 at a joint hearing of two subcommittees of the House Science, Space & Technology Committee. Mr. Hutchins is employed by Kryptos Logic.

U.S. officials are keenly aware that a similar attack could happen here. In June, the federally sponsored Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force issued a report on their year-long look at the state of the health care IT in this country. The task force was mandated by the Cybersecurity Act of 2015and formed in March 2016.

Specifically, the task force recommended:

• Defining and streamlining leadership, governance, and expectations for health care industry cybersecurity.

• Increasing the security and resilience of medical devices and health IT.

• Developing the health care workforce capacity necessary to prioritize and ensure cybersecurity awareness and technical capabilities.

• Increasing health care industry readiness through improved cybersecurity awareness and education.

• Identifying mechanisms to protect research and development efforts and intellectual property from attacks or exposure.

• Improving information sharing of industry threats, weaknesses, and mitigations.

Health care cybercrime is a significant problem in the United States. In 2016, 328 U.S. health care firms reported data breaches, up from 268 in 2015, with a total of 16.6 million Americans affected, according to a report conducted by Bitglass (registration required), a security software company. In February 2016, a hospital in California was forced to pay about $17,000 in Bitcoin, an electronic currency that is known to be favored by cybercriminals, to access electronic health records (EHRs) that were held in a similar manner to last month’s attack on the NHS.

For physicians, this may seem like someone else’s problem; however, unsafe day-to-day interactions with connected devices and patient EHRs were among the task force’s primary concerns.

For many, creating a safe password or not giving out critical information may seem like common sense, but many physicians are not able or willing to take the time to make sure they are interacting with systems safely, or they are overconfident in their security system, according to task force member Mark Jarrett, MD, senior vice president and chief quality officer at Northwell Health in New York.

“Most physicians now will try to access medical records of their patients who have been in the hospital because that’s good care,” Dr. Jarrett said in an interview. But they have to recognize that “they cannot give these passwords to other people and they need to make these passwords complex.”

“Phishing” is another concern. In a phishing scam, cybercriminals will pose as a fraudulent institution or individual in order to trick a target into downloading a virus, sending additional valuable information, or even paying money directly to the criminals.

“Physicians checking their emails need to be aware of possible phishing episodes, because they could be infected, and then there is the possibility that infection could be introduced into the system, Dr. Jarrett said. “I think the disconnect is [that physicians] are not used to [cybersecurity]. It’s not part of their daily life and they also, up until recently, thought ‘it’s never going to happen to me.’ ”

While hospitals are not completely incapable of protecting themselves, experts are concerned about an overinflated sense of confidence among health care professionals.

“Health care workers often assume that the IT network and the devices they support function efficiently and that their level of cybersecurity vulnerability is low,” according to the task force report.

This can be a costly assumption, financially, as well for safety; the price per stolen EHR averaged at $380 in 2016-2017, according to the Ponemon Institute’s 2017 Cost of Data Breach Study, released in June. That is nearly triple the average cost of all breaches – $141– and higher than the price of $241 for information stolen from financial industries because, unlike a credit card number, patients’ data are unique and cannot be replaced.

Aging equipment is another concern. Legacy software and machine systems used in medical practices and hospitals are not equipped with the necessary security services needed to handle the growing risks of connectivity, despite being included in the network.

“Every CT machine, every x-ray machine today is connected online, on one consolidated Internet” cybersecurity expert Idan Udi Edry of Trustifi said in an interview. “The more comfortable we are with the digital edge coming into our lives, the more vulnerable we become and the more security we need to implement to protect ourselves.”

Some solutions already have been suggested to help health care professionals replace their outdated equipment, especially private practice physicians or smaller hospitals without much financial wiggle room,

The cybersecurity task force report recommended creating health IT version of Cash for Clunkers, an Obama administration program that offered rebates to consumers who traded in older, less fuel efficient cars when purchasing a new car.

While experts agree that the growing focus on connected health care will continue to create cybersecurity risks, with all members of the health care industry working together, it is possible to keep hospitals and patients safe from would-be criminals.

The next key step is creating regulations that would encourage a cohesive structure of cybersecurity guidelines. According to the task force report, “a priority for regulatory agencies should be to ensure consistency among various federal and state cybersecurity regulations so that health care providers can focus on deploying their resources appropriately between securing patient information and the quality, safety, and accessibility of patient care” rather than having to focus on statutory and regulatory inconsistencies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

When computer hackers took control of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service using a virus known as “WannaCry,” doctors and nurses were left helpless, blocked from the files they would need to treat their patients until they paid to get them those files back.

Doctors were forced to revert to older methods, slowing everything to a snail’s pace.

The media coverage of the event was dramatic, but there is no doubt the effects made it justifiably so.

NHS hospitals had not achieved their goal of being paperless; had they been, the service would have been completely unable to stop the attack.

It was not just software that was affected but medical devices as well. Physicians were unable to perform x-rays, and some hospitals found that the refrigerators used to store blood products were shut down.

While the NHS was particularly vulnerable to the WannaCry because of budget cuts, this cybercrime could have happened to any hospital, and its lessons are applicable far all.

Doctors do understand the value of patients records, but they seem to be unaware of the physical harm that could befall patients from a cyberattack.

This attack needs to serve as a wake-up call for health care professionals who are not invested in their facilities’ cybersecurity practices.

Underfunding left NHS hospitals terribly exposed and, if physicians continue to be complacent with how to handle this issue, the results are sure to be more severe.

Rachel Clarke, MD, is at Oxford (England) University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and Taryn Youngstein, MD, is at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London. They reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Their remarks were make in a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1706754).

When computer hackers took control of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service using a virus known as “WannaCry,” doctors and nurses were left helpless, blocked from the files they would need to treat their patients until they paid to get them those files back.

Doctors were forced to revert to older methods, slowing everything to a snail’s pace.

The media coverage of the event was dramatic, but there is no doubt the effects made it justifiably so.

NHS hospitals had not achieved their goal of being paperless; had they been, the service would have been completely unable to stop the attack.

It was not just software that was affected but medical devices as well. Physicians were unable to perform x-rays, and some hospitals found that the refrigerators used to store blood products were shut down.

While the NHS was particularly vulnerable to the WannaCry because of budget cuts, this cybercrime could have happened to any hospital, and its lessons are applicable far all.

Doctors do understand the value of patients records, but they seem to be unaware of the physical harm that could befall patients from a cyberattack.

This attack needs to serve as a wake-up call for health care professionals who are not invested in their facilities’ cybersecurity practices.

Underfunding left NHS hospitals terribly exposed and, if physicians continue to be complacent with how to handle this issue, the results are sure to be more severe.

Rachel Clarke, MD, is at Oxford (England) University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and Taryn Youngstein, MD, is at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London. They reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Their remarks were make in a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1706754).

When computer hackers took control of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service using a virus known as “WannaCry,” doctors and nurses were left helpless, blocked from the files they would need to treat their patients until they paid to get them those files back.

Doctors were forced to revert to older methods, slowing everything to a snail’s pace.

The media coverage of the event was dramatic, but there is no doubt the effects made it justifiably so.

NHS hospitals had not achieved their goal of being paperless; had they been, the service would have been completely unable to stop the attack.

It was not just software that was affected but medical devices as well. Physicians were unable to perform x-rays, and some hospitals found that the refrigerators used to store blood products were shut down.

While the NHS was particularly vulnerable to the WannaCry because of budget cuts, this cybercrime could have happened to any hospital, and its lessons are applicable far all.

Doctors do understand the value of patients records, but they seem to be unaware of the physical harm that could befall patients from a cyberattack.

This attack needs to serve as a wake-up call for health care professionals who are not invested in their facilities’ cybersecurity practices.

Underfunding left NHS hospitals terribly exposed and, if physicians continue to be complacent with how to handle this issue, the results are sure to be more severe.

Rachel Clarke, MD, is at Oxford (England) University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and Taryn Youngstein, MD, is at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London. They reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Their remarks were make in a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1706754).

Aging equipment, valuable data, and an improperly trained workforce make health care IT extraordinarily vulnerable to external malfeasance, as demonstrated by the WannaCry virus episode that occurred this spring in the United Kingdom.

Computer hackers used a weakness in the operating system employed by the U.K. National Health Service, allowing the WannaCry virus to spread quickly across connected systems. The ransomware attack locked clinicians out of patient records and diagnostic machines that were connected, bringing patient care to a near standstill.

The attack lasted 3 days until Marcus Hutchins, a 22-year-old security researcher, stumbled onto a way to slow the spread of the virus enough to manage it, but not before nearly 60 million attacks had been conducted, Salim Neino, CEO of Kryptos Logic, testified June 15 at a joint hearing of two subcommittees of the House Science, Space & Technology Committee. Mr. Hutchins is employed by Kryptos Logic.

U.S. officials are keenly aware that a similar attack could happen here. In June, the federally sponsored Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force issued a report on their year-long look at the state of the health care IT in this country. The task force was mandated by the Cybersecurity Act of 2015and formed in March 2016.

Specifically, the task force recommended:

• Defining and streamlining leadership, governance, and expectations for health care industry cybersecurity.

• Increasing the security and resilience of medical devices and health IT.

• Developing the health care workforce capacity necessary to prioritize and ensure cybersecurity awareness and technical capabilities.

• Increasing health care industry readiness through improved cybersecurity awareness and education.

• Identifying mechanisms to protect research and development efforts and intellectual property from attacks or exposure.

• Improving information sharing of industry threats, weaknesses, and mitigations.

Health care cybercrime is a significant problem in the United States. In 2016, 328 U.S. health care firms reported data breaches, up from 268 in 2015, with a total of 16.6 million Americans affected, according to a report conducted by Bitglass (registration required), a security software company. In February 2016, a hospital in California was forced to pay about $17,000 in Bitcoin, an electronic currency that is known to be favored by cybercriminals, to access electronic health records (EHRs) that were held in a similar manner to last month’s attack on the NHS.

For physicians, this may seem like someone else’s problem; however, unsafe day-to-day interactions with connected devices and patient EHRs were among the task force’s primary concerns.

For many, creating a safe password or not giving out critical information may seem like common sense, but many physicians are not able or willing to take the time to make sure they are interacting with systems safely, or they are overconfident in their security system, according to task force member Mark Jarrett, MD, senior vice president and chief quality officer at Northwell Health in New York.

“Most physicians now will try to access medical records of their patients who have been in the hospital because that’s good care,” Dr. Jarrett said in an interview. But they have to recognize that “they cannot give these passwords to other people and they need to make these passwords complex.”

“Phishing” is another concern. In a phishing scam, cybercriminals will pose as a fraudulent institution or individual in order to trick a target into downloading a virus, sending additional valuable information, or even paying money directly to the criminals.

“Physicians checking their emails need to be aware of possible phishing episodes, because they could be infected, and then there is the possibility that infection could be introduced into the system, Dr. Jarrett said. “I think the disconnect is [that physicians] are not used to [cybersecurity]. It’s not part of their daily life and they also, up until recently, thought ‘it’s never going to happen to me.’ ”

While hospitals are not completely incapable of protecting themselves, experts are concerned about an overinflated sense of confidence among health care professionals.

“Health care workers often assume that the IT network and the devices they support function efficiently and that their level of cybersecurity vulnerability is low,” according to the task force report.

This can be a costly assumption, financially, as well for safety; the price per stolen EHR averaged at $380 in 2016-2017, according to the Ponemon Institute’s 2017 Cost of Data Breach Study, released in June. That is nearly triple the average cost of all breaches – $141– and higher than the price of $241 for information stolen from financial industries because, unlike a credit card number, patients’ data are unique and cannot be replaced.

Aging equipment is another concern. Legacy software and machine systems used in medical practices and hospitals are not equipped with the necessary security services needed to handle the growing risks of connectivity, despite being included in the network.

“Every CT machine, every x-ray machine today is connected online, on one consolidated Internet” cybersecurity expert Idan Udi Edry of Trustifi said in an interview. “The more comfortable we are with the digital edge coming into our lives, the more vulnerable we become and the more security we need to implement to protect ourselves.”

Some solutions already have been suggested to help health care professionals replace their outdated equipment, especially private practice physicians or smaller hospitals without much financial wiggle room,

The cybersecurity task force report recommended creating health IT version of Cash for Clunkers, an Obama administration program that offered rebates to consumers who traded in older, less fuel efficient cars when purchasing a new car.

While experts agree that the growing focus on connected health care will continue to create cybersecurity risks, with all members of the health care industry working together, it is possible to keep hospitals and patients safe from would-be criminals.

The next key step is creating regulations that would encourage a cohesive structure of cybersecurity guidelines. According to the task force report, “a priority for regulatory agencies should be to ensure consistency among various federal and state cybersecurity regulations so that health care providers can focus on deploying their resources appropriately between securing patient information and the quality, safety, and accessibility of patient care” rather than having to focus on statutory and regulatory inconsistencies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Aging equipment, valuable data, and an improperly trained workforce make health care IT extraordinarily vulnerable to external malfeasance, as demonstrated by the WannaCry virus episode that occurred this spring in the United Kingdom.

Computer hackers used a weakness in the operating system employed by the U.K. National Health Service, allowing the WannaCry virus to spread quickly across connected systems. The ransomware attack locked clinicians out of patient records and diagnostic machines that were connected, bringing patient care to a near standstill.

The attack lasted 3 days until Marcus Hutchins, a 22-year-old security researcher, stumbled onto a way to slow the spread of the virus enough to manage it, but not before nearly 60 million attacks had been conducted, Salim Neino, CEO of Kryptos Logic, testified June 15 at a joint hearing of two subcommittees of the House Science, Space & Technology Committee. Mr. Hutchins is employed by Kryptos Logic.

U.S. officials are keenly aware that a similar attack could happen here. In June, the federally sponsored Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force issued a report on their year-long look at the state of the health care IT in this country. The task force was mandated by the Cybersecurity Act of 2015and formed in March 2016.

Specifically, the task force recommended:

• Defining and streamlining leadership, governance, and expectations for health care industry cybersecurity.

• Increasing the security and resilience of medical devices and health IT.

• Developing the health care workforce capacity necessary to prioritize and ensure cybersecurity awareness and technical capabilities.

• Increasing health care industry readiness through improved cybersecurity awareness and education.

• Identifying mechanisms to protect research and development efforts and intellectual property from attacks or exposure.

• Improving information sharing of industry threats, weaknesses, and mitigations.

Health care cybercrime is a significant problem in the United States. In 2016, 328 U.S. health care firms reported data breaches, up from 268 in 2015, with a total of 16.6 million Americans affected, according to a report conducted by Bitglass (registration required), a security software company. In February 2016, a hospital in California was forced to pay about $17,000 in Bitcoin, an electronic currency that is known to be favored by cybercriminals, to access electronic health records (EHRs) that were held in a similar manner to last month’s attack on the NHS.

For physicians, this may seem like someone else’s problem; however, unsafe day-to-day interactions with connected devices and patient EHRs were among the task force’s primary concerns.

For many, creating a safe password or not giving out critical information may seem like common sense, but many physicians are not able or willing to take the time to make sure they are interacting with systems safely, or they are overconfident in their security system, according to task force member Mark Jarrett, MD, senior vice president and chief quality officer at Northwell Health in New York.

“Most physicians now will try to access medical records of their patients who have been in the hospital because that’s good care,” Dr. Jarrett said in an interview. But they have to recognize that “they cannot give these passwords to other people and they need to make these passwords complex.”

“Phishing” is another concern. In a phishing scam, cybercriminals will pose as a fraudulent institution or individual in order to trick a target into downloading a virus, sending additional valuable information, or even paying money directly to the criminals.

“Physicians checking their emails need to be aware of possible phishing episodes, because they could be infected, and then there is the possibility that infection could be introduced into the system, Dr. Jarrett said. “I think the disconnect is [that physicians] are not used to [cybersecurity]. It’s not part of their daily life and they also, up until recently, thought ‘it’s never going to happen to me.’ ”

While hospitals are not completely incapable of protecting themselves, experts are concerned about an overinflated sense of confidence among health care professionals.

“Health care workers often assume that the IT network and the devices they support function efficiently and that their level of cybersecurity vulnerability is low,” according to the task force report.

This can be a costly assumption, financially, as well for safety; the price per stolen EHR averaged at $380 in 2016-2017, according to the Ponemon Institute’s 2017 Cost of Data Breach Study, released in June. That is nearly triple the average cost of all breaches – $141– and higher than the price of $241 for information stolen from financial industries because, unlike a credit card number, patients’ data are unique and cannot be replaced.

Aging equipment is another concern. Legacy software and machine systems used in medical practices and hospitals are not equipped with the necessary security services needed to handle the growing risks of connectivity, despite being included in the network.

“Every CT machine, every x-ray machine today is connected online, on one consolidated Internet” cybersecurity expert Idan Udi Edry of Trustifi said in an interview. “The more comfortable we are with the digital edge coming into our lives, the more vulnerable we become and the more security we need to implement to protect ourselves.”

Some solutions already have been suggested to help health care professionals replace their outdated equipment, especially private practice physicians or smaller hospitals without much financial wiggle room,

The cybersecurity task force report recommended creating health IT version of Cash for Clunkers, an Obama administration program that offered rebates to consumers who traded in older, less fuel efficient cars when purchasing a new car.

While experts agree that the growing focus on connected health care will continue to create cybersecurity risks, with all members of the health care industry working together, it is possible to keep hospitals and patients safe from would-be criminals.

The next key step is creating regulations that would encourage a cohesive structure of cybersecurity guidelines. According to the task force report, “a priority for regulatory agencies should be to ensure consistency among various federal and state cybersecurity regulations so that health care providers can focus on deploying their resources appropriately between securing patient information and the quality, safety, and accessibility of patient care” rather than having to focus on statutory and regulatory inconsistencies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets