User login

Despite increasing media coverage of human trafficking and the gravity of its many ramifications, I am struck by how often trainees and other clinicians present to me patients for which trafficking is a real potential concern—yet who give me a blank expression when I ask if anyone has screened these patients for being victims of trafficking. I suspect that few of us anticipated, during medical training, that we would be providing care to women who are enslaved.

How large is the problem?

It is impossible to comprehend the true scope of human trafficking. Estimates are that 20.9 million men, women, and children globally are forced into work that they are not free to leave.1

Although human trafficking is recognized as a global phenomenon, its prevalence in the United States is significant enough that it should prompt the health care community to engage in helping identify and assist victims/survivors: From January until June of 2017, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received 13,807 telephone calls, resulting in reporting of 4,460 cases.2 Indeed, from 2015 to 2016 there was a 35.7% increase in the number of hotline cases reported, for a total of 7,572 (6,340—more than 80%—of which regarded females). California had the most cases reported (1,323), followed by Texas (670) and Florida (550); those 3 states also reported an increase in trafficking crime. Vermont (5), Rhode Island (9), and Alaska (10) reported the fewest calls.3

How is trafficking defined?

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defines “trafficking in persons” as:

… recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.4

Traffickers prey on potentially vulnerable people. Girls and young women who have experienced poverty, homelessness, childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse, gender nonconformity, mental illness, or developmental delay are at particular risk.5 Children who have had interactions with Child Protective Services, come from a dysfunctional family, or have lived in a community with high crime, political or social unrest, corruption, or gender bias and discrimination are also at increased risk.6

Read about clues that raise clinical suspicion

Clues that raise clinical suspicion

A number of potential signs should make providers suspicious about potential human trafficking. Some of those signs are similar to the red flags we see in intimate partner violence, such as:

- having a difficult time talking to the patient alone

- having the accompanying person answer the patient’s questions

- body language that suggests fear, anxiety, or distrust (eg, shifting positions, looking away, appearing withdrawn)

- physical examination inconsistent with the history

- physical injury (especially multiple injuries or injuries in various stages of healing)

- refusal of interpreter services.

Trafficked girls or women may appear overly familiar with sex, have unexpected material possessions, or appear to be giving scripted or memorized answers to queries.7 Traffickers often confiscate their victims’ personal identification. They try to prevent victims from knowing their geographic locales: Patients might not have any documentation or awareness of exact surroundings (eg, their home address). Patients may be wearing clothes considered inappropriate for the weather or venue. They may have tattoos that are marks of branding.8

Medical consequences of being trafficked are obvious, numerous, and serious

Many medical sequelae that result from trafficking are obvious, given the nature of work that victims are forced to do. For example, overcrowding can lead to infectious disease, such as tuberculosis.9 Inadequate access to preventive or basic medical services can result in weight loss, poor dentition, and untreated chronic medical conditions.

If victims are experiencing physical or sexual abuse, they can present with evidence of blunt trauma, ligature marks, skin burns, wounds inflicted by weapons, and vaginal lacerations.10 A study found that 63% of survivors reported at least 10 somatic symptoms, including headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, abdominal or pelvic pain, memory loss, and symptoms of genital infectious disease.11

Girls and women being trafficked for sex may experience many of the sequelae of unprotected intercourse: irregular bleeding, unintended pregnancy, unwanted or unsafe pregnancy termination, vaginal trauma, and sexually transmitted infection (STI).12 In a study of trafficking survivors, 38% were HIV-positive.13

Trafficking survivors can suffer myriad mental health conditions, with high rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and suicidal ideation.14 A study of 387 survivors found that 12% had attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide the month before they were interviewed.15

Substance abuse is also a common problem among trafficking victims.16 One survivor interviewed in a recent study said:

It was much more difficult to work sober because I was dealing with emotions or the pain that I was feeling during intercourse, because when you have sex with people 8, 9, 10 times a day, even more than that, it starts to hurt a lot. And being high made it easier to deal with that and also it made it easier for me to get away from my body while it was happening, place my brain somewhere else.17

Because of the substantial risk of mental health problems, including substance abuse, among trafficking survivors, the physical exam of a patient should include careful assessment of demeanor and mental health status. Of course, comprehensive inspection for signs of physical or blunt trauma is paramount.

Read about Patient and staff safety during the visit

Patient and staff safety during the visit

Providers should be aware of potential safety concerns, both for the patient and for the staff. Creative strategies should be utilized to screen the patient in private. The use of interpreter services—either in person or over the telephone—should be presented and facilitated as being a routine part of practice. Any person who accompanies the patient should be asked to leave the examining room, either as a statement of practice routine or under the guise of having him (or her) step out to obtain paperwork or provide documentation.

Care of victims

Trauma-informed care should be a guiding principle for trafficking survivors. This involves empowering the patient, who may feel victimized again if asked to undress and undergo multiple physical examinations. Macias-Konstantopoulos noted: “A trauma-informed approach to care acknowledges the pervasiveness and effect of trauma across the life span of the individual, recognizes the vulnerabilities and emotional triggers of trauma survivors, minimizes repeated traumatization and fosters physical, psychological, and emotional safety, recovery, health and well-being.”18

The patient should be counseled that she has control over her body and can guide different aspects of the examination. For example the provider should discuss: 1) the amount of clothing deemed optimal for an examination, 2) the availability of a support person during the exam (for instance, a nurse or a social worker) if the patient requests one, and 3) utilization of whatever strategies the patient deems optimal for her to be most comfortable during the exam (such as leaving the door slightly ajar or having a mutually agreed-on signal to interrupt the exam).

Routine health care maintenance should be offered, including an assessment of overall physical and dental health and screening for STI and mental health. Screening for substances of abuse should be considered. If indicated, emergency contraception, postexposure HIV prophylaxis, immunizations, and empiric antibiotics for STI should be offered.19

Screening when indicated by evidence, suspicion, or concern

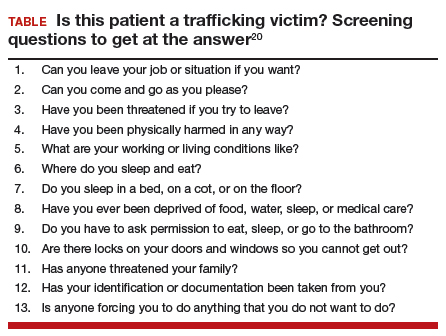

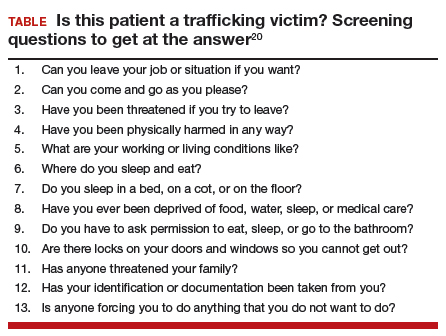

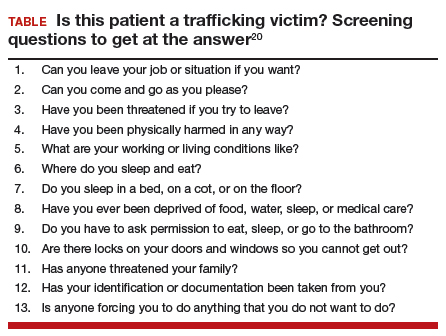

Unlike the case with intimate partner violence, experts do not recommend universal screening for human trafficking. Clinicians should be comfortable, however, trying to elicit that history when a concern arises, either because of identified risk factors, red flags, or concerns that arise from the findings of the history or physical. Ideally, clinicians should consider becoming comfortable choosing a few screening questions to regularly incorporate into their assessment. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) offers a list of questions that can be utilized (TABLE).20

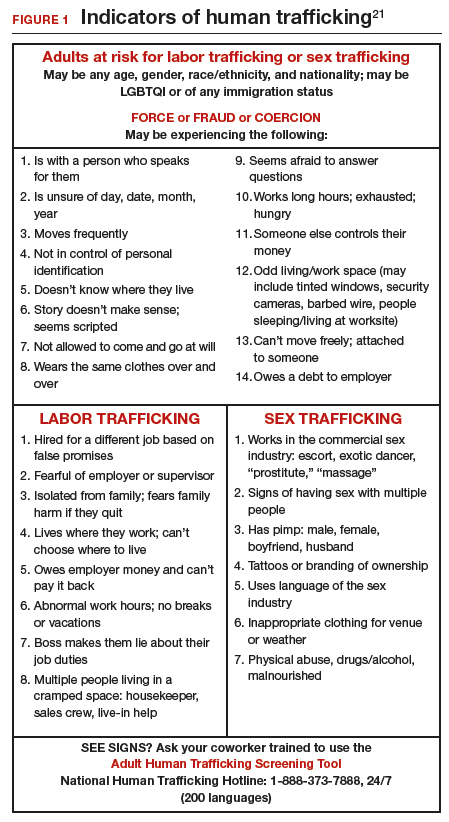

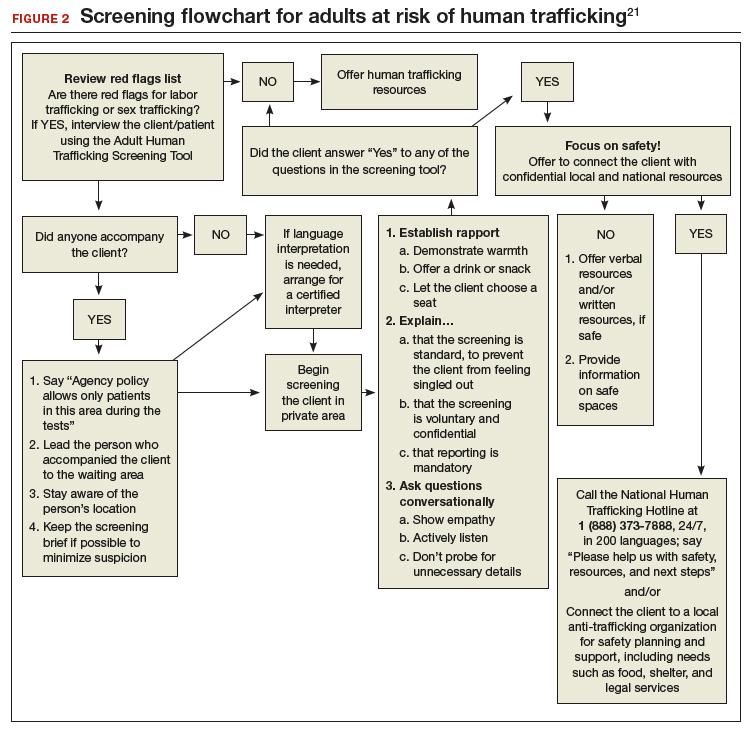

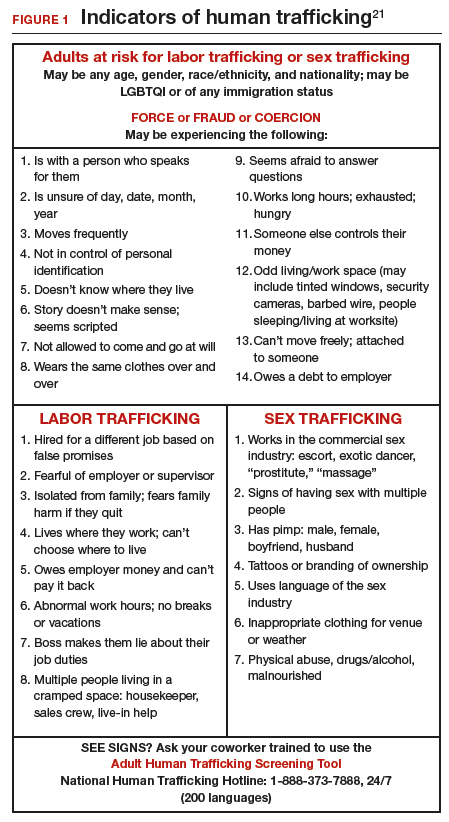

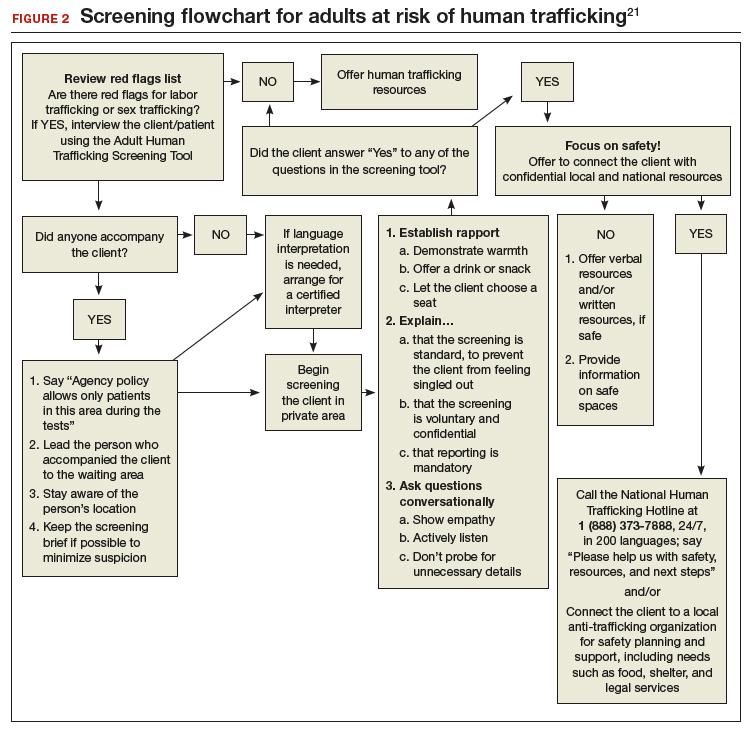

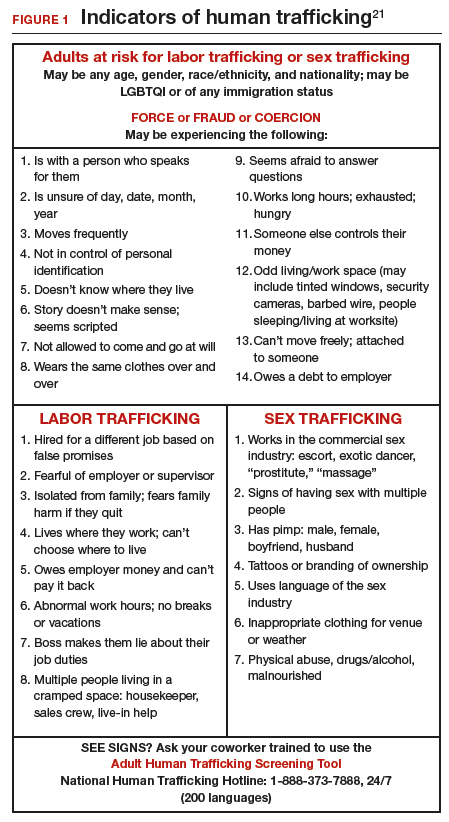

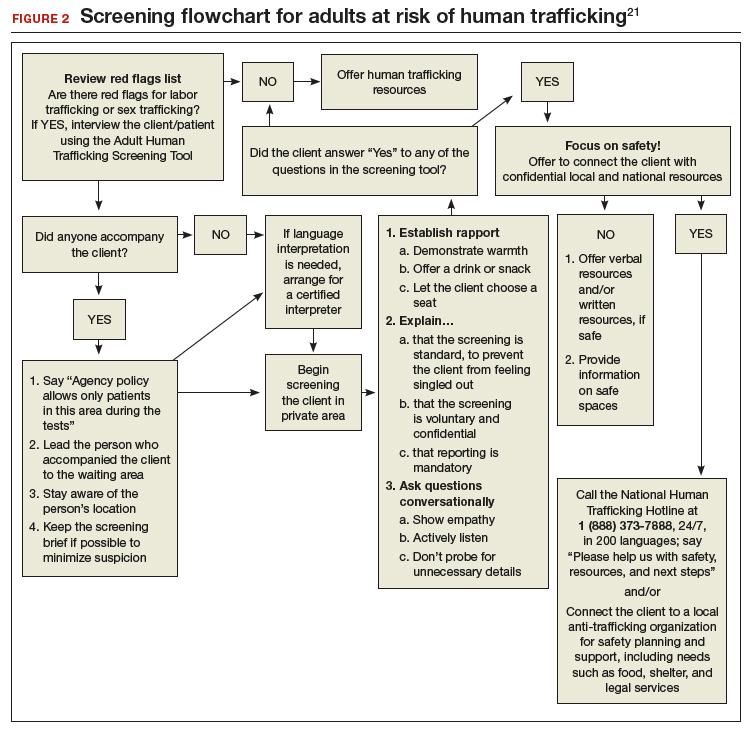

In January 2018, the Office on Trafficking in Persons, a unit of the HHS Administration for Children and Families, released an “Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide.” The document includes 2 excellent tools21 that clinicians can utilize to identify patients who should be screened and how to identify and assist survivors (FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2).

Clinicians, in their encounters with patients, are particularly well-positioned to intersect with, and identify, survivors. Regrettably, such opportunities are often missed—and victims thus remain unidentified and trapped in their circumstances. A study revealed that one-half of survivors who were interviewed reported seeing a physician while they were being trafficked.22 Even more alarming, another study showed that 87.8% of survivors had received health care during their captivity.23 It is dismaying to know that these patients left those health care settings without receiving the assistance they truly need and with their true circumstances remaining unidentified.

Read about Finding assistance and support

Finding assistance and support

Centers in the United States now provide trauma-informed care for trafficking survivors in a confidential setting (see “Specialized care is increasingly available”).24 A physician who works at a center in New York City noted: “Our survivors told us that more than fear or pain, the feelings that sat with them most often were worthlessness and invisibility. We can do better as physicians and as educators to expose this epidemic and care for its victims.”24

Here is a sampling of the growing number of centers in the United States that provide trauma-centered care for survivors of human trafficking:

- Survivor Clinic at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

- EMPOWER Clinic for Survivors of Sex Trafficking and Sexual Violence at NYU Langone Health, New York, New York

- Freedom Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- The Hope Through Health Clinic, Austin, Texas

- Pacific Survivor Center, Honolulu, Hawaii

Most clinicians practice in settings that do not have easy access to such subspecialized centers, however. For them, the National Human Trafficking Hotline can be an invaluable resource (see “Hotline is a valuable resource”).25 Law enforcement and social services colleagues also can be useful allies.

Uncertain how you can help a patient who is a victim of human trafficking? For assistance and support, contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline--24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and in 200 languages--in any of 3 ways:

- By telephone: (888) 373-7888

- By text: 233733

- On the web: https://humantraffickinghotline.orga

aIncludes a search field that clinicians can use to look up the nearest resources for additional assistance.

Let’s turn our concern and awareness into results

We, as providers of women’s health care, are uniquely positioned to help these most vulnerable of people, many of whom have been stripped of personal documents and denied access to financial resources and community support. As a medical community, we should strive to combat this tragic epidemic, 1 patient at a time.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- International Labour Organization. New ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour: 20.9 million victims. http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_182109/lang--en/index.htm. Published June 2012. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. Hotline statistics. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Cone A. Report: Human trafficking in U.S. rose 35.7 percent in one year. United Press International (UPI). https://www.upi.com/Report-Human-trafficking-in-US-rose-357-percent-in-one-year/5571486328579. Published February 5, 2017. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Human trafficking. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Risk factors for and consequences of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. In Clayton E, Krugman R, Simon P, eds; Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

- Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015:135(3);566–574.

- Alpert E, Ahn R, Albright E, Purcell G, Burke T, Macias-Konstantanopoulos W. Human Trafficking: Guidebook on Identification, Assessment, and Response in the Health Care Setting. Waltham, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts Medical Society; 2014. http://www.massmed.org/Patient-Care/Health-Topics/Violence-Prevention-and-Intervention/Human-Trafficking-(pdf). Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Steele S. Human trafficking, labor brokering, and mining in southern Africa: responding to a decentralized and hidden public health disaster. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(4):665–680.

- Becker HJ, Bechtel K. Recognizing victims of human trafficking in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(2):144–147.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering postrafficking services in Europe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):55–59.

- Tracy EE, Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Identifying and assisting sexually exploited and trafficked patients seeking women’s health care services. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):443–453.

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542.

- Rafferty Y. Child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: a review of promising prevention policies and programs. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(4):559–575.

- Kiss L, Yun K, Pocock N, Zimmerman C. Exploitation, violence, and suicide risk among child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):e152278.

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, Stoklosa J. Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):23–34.

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, Shea JA. Trafficking and trauma: insight and advice for the healthcare system from sex-trafficked women incarcerated on Rikers Island. Med Care. 2017;55(12):1017–1022.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Human trafficking: the role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Ann Intern Med. 2016:165(8):582–588.

- Chung RJ, English A. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):427–433.

- Resources: Screening tool for victims of human trafficking. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndia/legacy/2011/10/14/health_screen_questions.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. January 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):e36–e49.

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in health-care facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:61–91.

- Geynisman-Tan JM, Taylor JS, Edersheim T, Taubel D. All the darkness we don’t see. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):135.e1–e5.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. https://humantraffickinghotline.org. Accessed May 30, 2018.

Despite increasing media coverage of human trafficking and the gravity of its many ramifications, I am struck by how often trainees and other clinicians present to me patients for which trafficking is a real potential concern—yet who give me a blank expression when I ask if anyone has screened these patients for being victims of trafficking. I suspect that few of us anticipated, during medical training, that we would be providing care to women who are enslaved.

How large is the problem?

It is impossible to comprehend the true scope of human trafficking. Estimates are that 20.9 million men, women, and children globally are forced into work that they are not free to leave.1

Although human trafficking is recognized as a global phenomenon, its prevalence in the United States is significant enough that it should prompt the health care community to engage in helping identify and assist victims/survivors: From January until June of 2017, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received 13,807 telephone calls, resulting in reporting of 4,460 cases.2 Indeed, from 2015 to 2016 there was a 35.7% increase in the number of hotline cases reported, for a total of 7,572 (6,340—more than 80%—of which regarded females). California had the most cases reported (1,323), followed by Texas (670) and Florida (550); those 3 states also reported an increase in trafficking crime. Vermont (5), Rhode Island (9), and Alaska (10) reported the fewest calls.3

How is trafficking defined?

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defines “trafficking in persons” as:

… recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.4

Traffickers prey on potentially vulnerable people. Girls and young women who have experienced poverty, homelessness, childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse, gender nonconformity, mental illness, or developmental delay are at particular risk.5 Children who have had interactions with Child Protective Services, come from a dysfunctional family, or have lived in a community with high crime, political or social unrest, corruption, or gender bias and discrimination are also at increased risk.6

Read about clues that raise clinical suspicion

Clues that raise clinical suspicion

A number of potential signs should make providers suspicious about potential human trafficking. Some of those signs are similar to the red flags we see in intimate partner violence, such as:

- having a difficult time talking to the patient alone

- having the accompanying person answer the patient’s questions

- body language that suggests fear, anxiety, or distrust (eg, shifting positions, looking away, appearing withdrawn)

- physical examination inconsistent with the history

- physical injury (especially multiple injuries or injuries in various stages of healing)

- refusal of interpreter services.

Trafficked girls or women may appear overly familiar with sex, have unexpected material possessions, or appear to be giving scripted or memorized answers to queries.7 Traffickers often confiscate their victims’ personal identification. They try to prevent victims from knowing their geographic locales: Patients might not have any documentation or awareness of exact surroundings (eg, their home address). Patients may be wearing clothes considered inappropriate for the weather or venue. They may have tattoos that are marks of branding.8

Medical consequences of being trafficked are obvious, numerous, and serious

Many medical sequelae that result from trafficking are obvious, given the nature of work that victims are forced to do. For example, overcrowding can lead to infectious disease, such as tuberculosis.9 Inadequate access to preventive or basic medical services can result in weight loss, poor dentition, and untreated chronic medical conditions.

If victims are experiencing physical or sexual abuse, they can present with evidence of blunt trauma, ligature marks, skin burns, wounds inflicted by weapons, and vaginal lacerations.10 A study found that 63% of survivors reported at least 10 somatic symptoms, including headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, abdominal or pelvic pain, memory loss, and symptoms of genital infectious disease.11

Girls and women being trafficked for sex may experience many of the sequelae of unprotected intercourse: irregular bleeding, unintended pregnancy, unwanted or unsafe pregnancy termination, vaginal trauma, and sexually transmitted infection (STI).12 In a study of trafficking survivors, 38% were HIV-positive.13

Trafficking survivors can suffer myriad mental health conditions, with high rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and suicidal ideation.14 A study of 387 survivors found that 12% had attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide the month before they were interviewed.15

Substance abuse is also a common problem among trafficking victims.16 One survivor interviewed in a recent study said:

It was much more difficult to work sober because I was dealing with emotions or the pain that I was feeling during intercourse, because when you have sex with people 8, 9, 10 times a day, even more than that, it starts to hurt a lot. And being high made it easier to deal with that and also it made it easier for me to get away from my body while it was happening, place my brain somewhere else.17

Because of the substantial risk of mental health problems, including substance abuse, among trafficking survivors, the physical exam of a patient should include careful assessment of demeanor and mental health status. Of course, comprehensive inspection for signs of physical or blunt trauma is paramount.

Read about Patient and staff safety during the visit

Patient and staff safety during the visit

Providers should be aware of potential safety concerns, both for the patient and for the staff. Creative strategies should be utilized to screen the patient in private. The use of interpreter services—either in person or over the telephone—should be presented and facilitated as being a routine part of practice. Any person who accompanies the patient should be asked to leave the examining room, either as a statement of practice routine or under the guise of having him (or her) step out to obtain paperwork or provide documentation.

Care of victims

Trauma-informed care should be a guiding principle for trafficking survivors. This involves empowering the patient, who may feel victimized again if asked to undress and undergo multiple physical examinations. Macias-Konstantopoulos noted: “A trauma-informed approach to care acknowledges the pervasiveness and effect of trauma across the life span of the individual, recognizes the vulnerabilities and emotional triggers of trauma survivors, minimizes repeated traumatization and fosters physical, psychological, and emotional safety, recovery, health and well-being.”18

The patient should be counseled that she has control over her body and can guide different aspects of the examination. For example the provider should discuss: 1) the amount of clothing deemed optimal for an examination, 2) the availability of a support person during the exam (for instance, a nurse or a social worker) if the patient requests one, and 3) utilization of whatever strategies the patient deems optimal for her to be most comfortable during the exam (such as leaving the door slightly ajar or having a mutually agreed-on signal to interrupt the exam).

Routine health care maintenance should be offered, including an assessment of overall physical and dental health and screening for STI and mental health. Screening for substances of abuse should be considered. If indicated, emergency contraception, postexposure HIV prophylaxis, immunizations, and empiric antibiotics for STI should be offered.19

Screening when indicated by evidence, suspicion, or concern

Unlike the case with intimate partner violence, experts do not recommend universal screening for human trafficking. Clinicians should be comfortable, however, trying to elicit that history when a concern arises, either because of identified risk factors, red flags, or concerns that arise from the findings of the history or physical. Ideally, clinicians should consider becoming comfortable choosing a few screening questions to regularly incorporate into their assessment. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) offers a list of questions that can be utilized (TABLE).20

In January 2018, the Office on Trafficking in Persons, a unit of the HHS Administration for Children and Families, released an “Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide.” The document includes 2 excellent tools21 that clinicians can utilize to identify patients who should be screened and how to identify and assist survivors (FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2).

Clinicians, in their encounters with patients, are particularly well-positioned to intersect with, and identify, survivors. Regrettably, such opportunities are often missed—and victims thus remain unidentified and trapped in their circumstances. A study revealed that one-half of survivors who were interviewed reported seeing a physician while they were being trafficked.22 Even more alarming, another study showed that 87.8% of survivors had received health care during their captivity.23 It is dismaying to know that these patients left those health care settings without receiving the assistance they truly need and with their true circumstances remaining unidentified.

Read about Finding assistance and support

Finding assistance and support

Centers in the United States now provide trauma-informed care for trafficking survivors in a confidential setting (see “Specialized care is increasingly available”).24 A physician who works at a center in New York City noted: “Our survivors told us that more than fear or pain, the feelings that sat with them most often were worthlessness and invisibility. We can do better as physicians and as educators to expose this epidemic and care for its victims.”24

Here is a sampling of the growing number of centers in the United States that provide trauma-centered care for survivors of human trafficking:

- Survivor Clinic at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

- EMPOWER Clinic for Survivors of Sex Trafficking and Sexual Violence at NYU Langone Health, New York, New York

- Freedom Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- The Hope Through Health Clinic, Austin, Texas

- Pacific Survivor Center, Honolulu, Hawaii

Most clinicians practice in settings that do not have easy access to such subspecialized centers, however. For them, the National Human Trafficking Hotline can be an invaluable resource (see “Hotline is a valuable resource”).25 Law enforcement and social services colleagues also can be useful allies.

Uncertain how you can help a patient who is a victim of human trafficking? For assistance and support, contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline--24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and in 200 languages--in any of 3 ways:

- By telephone: (888) 373-7888

- By text: 233733

- On the web: https://humantraffickinghotline.orga

aIncludes a search field that clinicians can use to look up the nearest resources for additional assistance.

Let’s turn our concern and awareness into results

We, as providers of women’s health care, are uniquely positioned to help these most vulnerable of people, many of whom have been stripped of personal documents and denied access to financial resources and community support. As a medical community, we should strive to combat this tragic epidemic, 1 patient at a time.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Despite increasing media coverage of human trafficking and the gravity of its many ramifications, I am struck by how often trainees and other clinicians present to me patients for which trafficking is a real potential concern—yet who give me a blank expression when I ask if anyone has screened these patients for being victims of trafficking. I suspect that few of us anticipated, during medical training, that we would be providing care to women who are enslaved.

How large is the problem?

It is impossible to comprehend the true scope of human trafficking. Estimates are that 20.9 million men, women, and children globally are forced into work that they are not free to leave.1

Although human trafficking is recognized as a global phenomenon, its prevalence in the United States is significant enough that it should prompt the health care community to engage in helping identify and assist victims/survivors: From January until June of 2017, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received 13,807 telephone calls, resulting in reporting of 4,460 cases.2 Indeed, from 2015 to 2016 there was a 35.7% increase in the number of hotline cases reported, for a total of 7,572 (6,340—more than 80%—of which regarded females). California had the most cases reported (1,323), followed by Texas (670) and Florida (550); those 3 states also reported an increase in trafficking crime. Vermont (5), Rhode Island (9), and Alaska (10) reported the fewest calls.3

How is trafficking defined?

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defines “trafficking in persons” as:

… recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.4

Traffickers prey on potentially vulnerable people. Girls and young women who have experienced poverty, homelessness, childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse, gender nonconformity, mental illness, or developmental delay are at particular risk.5 Children who have had interactions with Child Protective Services, come from a dysfunctional family, or have lived in a community with high crime, political or social unrest, corruption, or gender bias and discrimination are also at increased risk.6

Read about clues that raise clinical suspicion

Clues that raise clinical suspicion

A number of potential signs should make providers suspicious about potential human trafficking. Some of those signs are similar to the red flags we see in intimate partner violence, such as:

- having a difficult time talking to the patient alone

- having the accompanying person answer the patient’s questions

- body language that suggests fear, anxiety, or distrust (eg, shifting positions, looking away, appearing withdrawn)

- physical examination inconsistent with the history

- physical injury (especially multiple injuries or injuries in various stages of healing)

- refusal of interpreter services.

Trafficked girls or women may appear overly familiar with sex, have unexpected material possessions, or appear to be giving scripted or memorized answers to queries.7 Traffickers often confiscate their victims’ personal identification. They try to prevent victims from knowing their geographic locales: Patients might not have any documentation or awareness of exact surroundings (eg, their home address). Patients may be wearing clothes considered inappropriate for the weather or venue. They may have tattoos that are marks of branding.8

Medical consequences of being trafficked are obvious, numerous, and serious

Many medical sequelae that result from trafficking are obvious, given the nature of work that victims are forced to do. For example, overcrowding can lead to infectious disease, such as tuberculosis.9 Inadequate access to preventive or basic medical services can result in weight loss, poor dentition, and untreated chronic medical conditions.

If victims are experiencing physical or sexual abuse, they can present with evidence of blunt trauma, ligature marks, skin burns, wounds inflicted by weapons, and vaginal lacerations.10 A study found that 63% of survivors reported at least 10 somatic symptoms, including headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, abdominal or pelvic pain, memory loss, and symptoms of genital infectious disease.11

Girls and women being trafficked for sex may experience many of the sequelae of unprotected intercourse: irregular bleeding, unintended pregnancy, unwanted or unsafe pregnancy termination, vaginal trauma, and sexually transmitted infection (STI).12 In a study of trafficking survivors, 38% were HIV-positive.13

Trafficking survivors can suffer myriad mental health conditions, with high rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and suicidal ideation.14 A study of 387 survivors found that 12% had attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide the month before they were interviewed.15

Substance abuse is also a common problem among trafficking victims.16 One survivor interviewed in a recent study said:

It was much more difficult to work sober because I was dealing with emotions or the pain that I was feeling during intercourse, because when you have sex with people 8, 9, 10 times a day, even more than that, it starts to hurt a lot. And being high made it easier to deal with that and also it made it easier for me to get away from my body while it was happening, place my brain somewhere else.17

Because of the substantial risk of mental health problems, including substance abuse, among trafficking survivors, the physical exam of a patient should include careful assessment of demeanor and mental health status. Of course, comprehensive inspection for signs of physical or blunt trauma is paramount.

Read about Patient and staff safety during the visit

Patient and staff safety during the visit

Providers should be aware of potential safety concerns, both for the patient and for the staff. Creative strategies should be utilized to screen the patient in private. The use of interpreter services—either in person or over the telephone—should be presented and facilitated as being a routine part of practice. Any person who accompanies the patient should be asked to leave the examining room, either as a statement of practice routine or under the guise of having him (or her) step out to obtain paperwork or provide documentation.

Care of victims

Trauma-informed care should be a guiding principle for trafficking survivors. This involves empowering the patient, who may feel victimized again if asked to undress and undergo multiple physical examinations. Macias-Konstantopoulos noted: “A trauma-informed approach to care acknowledges the pervasiveness and effect of trauma across the life span of the individual, recognizes the vulnerabilities and emotional triggers of trauma survivors, minimizes repeated traumatization and fosters physical, psychological, and emotional safety, recovery, health and well-being.”18

The patient should be counseled that she has control over her body and can guide different aspects of the examination. For example the provider should discuss: 1) the amount of clothing deemed optimal for an examination, 2) the availability of a support person during the exam (for instance, a nurse or a social worker) if the patient requests one, and 3) utilization of whatever strategies the patient deems optimal for her to be most comfortable during the exam (such as leaving the door slightly ajar or having a mutually agreed-on signal to interrupt the exam).

Routine health care maintenance should be offered, including an assessment of overall physical and dental health and screening for STI and mental health. Screening for substances of abuse should be considered. If indicated, emergency contraception, postexposure HIV prophylaxis, immunizations, and empiric antibiotics for STI should be offered.19

Screening when indicated by evidence, suspicion, or concern

Unlike the case with intimate partner violence, experts do not recommend universal screening for human trafficking. Clinicians should be comfortable, however, trying to elicit that history when a concern arises, either because of identified risk factors, red flags, or concerns that arise from the findings of the history or physical. Ideally, clinicians should consider becoming comfortable choosing a few screening questions to regularly incorporate into their assessment. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) offers a list of questions that can be utilized (TABLE).20

In January 2018, the Office on Trafficking in Persons, a unit of the HHS Administration for Children and Families, released an “Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide.” The document includes 2 excellent tools21 that clinicians can utilize to identify patients who should be screened and how to identify and assist survivors (FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2).

Clinicians, in their encounters with patients, are particularly well-positioned to intersect with, and identify, survivors. Regrettably, such opportunities are often missed—and victims thus remain unidentified and trapped in their circumstances. A study revealed that one-half of survivors who were interviewed reported seeing a physician while they were being trafficked.22 Even more alarming, another study showed that 87.8% of survivors had received health care during their captivity.23 It is dismaying to know that these patients left those health care settings without receiving the assistance they truly need and with their true circumstances remaining unidentified.

Read about Finding assistance and support

Finding assistance and support

Centers in the United States now provide trauma-informed care for trafficking survivors in a confidential setting (see “Specialized care is increasingly available”).24 A physician who works at a center in New York City noted: “Our survivors told us that more than fear or pain, the feelings that sat with them most often were worthlessness and invisibility. We can do better as physicians and as educators to expose this epidemic and care for its victims.”24

Here is a sampling of the growing number of centers in the United States that provide trauma-centered care for survivors of human trafficking:

- Survivor Clinic at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

- EMPOWER Clinic for Survivors of Sex Trafficking and Sexual Violence at NYU Langone Health, New York, New York

- Freedom Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- The Hope Through Health Clinic, Austin, Texas

- Pacific Survivor Center, Honolulu, Hawaii

Most clinicians practice in settings that do not have easy access to such subspecialized centers, however. For them, the National Human Trafficking Hotline can be an invaluable resource (see “Hotline is a valuable resource”).25 Law enforcement and social services colleagues also can be useful allies.

Uncertain how you can help a patient who is a victim of human trafficking? For assistance and support, contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline--24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and in 200 languages--in any of 3 ways:

- By telephone: (888) 373-7888

- By text: 233733

- On the web: https://humantraffickinghotline.orga

aIncludes a search field that clinicians can use to look up the nearest resources for additional assistance.

Let’s turn our concern and awareness into results

We, as providers of women’s health care, are uniquely positioned to help these most vulnerable of people, many of whom have been stripped of personal documents and denied access to financial resources and community support. As a medical community, we should strive to combat this tragic epidemic, 1 patient at a time.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- International Labour Organization. New ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour: 20.9 million victims. http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_182109/lang--en/index.htm. Published June 2012. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. Hotline statistics. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Cone A. Report: Human trafficking in U.S. rose 35.7 percent in one year. United Press International (UPI). https://www.upi.com/Report-Human-trafficking-in-US-rose-357-percent-in-one-year/5571486328579. Published February 5, 2017. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Human trafficking. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Risk factors for and consequences of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. In Clayton E, Krugman R, Simon P, eds; Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

- Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015:135(3);566–574.

- Alpert E, Ahn R, Albright E, Purcell G, Burke T, Macias-Konstantanopoulos W. Human Trafficking: Guidebook on Identification, Assessment, and Response in the Health Care Setting. Waltham, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts Medical Society; 2014. http://www.massmed.org/Patient-Care/Health-Topics/Violence-Prevention-and-Intervention/Human-Trafficking-(pdf). Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Steele S. Human trafficking, labor brokering, and mining in southern Africa: responding to a decentralized and hidden public health disaster. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(4):665–680.

- Becker HJ, Bechtel K. Recognizing victims of human trafficking in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(2):144–147.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering postrafficking services in Europe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):55–59.

- Tracy EE, Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Identifying and assisting sexually exploited and trafficked patients seeking women’s health care services. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):443–453.

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542.

- Rafferty Y. Child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: a review of promising prevention policies and programs. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(4):559–575.

- Kiss L, Yun K, Pocock N, Zimmerman C. Exploitation, violence, and suicide risk among child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):e152278.

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, Stoklosa J. Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):23–34.

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, Shea JA. Trafficking and trauma: insight and advice for the healthcare system from sex-trafficked women incarcerated on Rikers Island. Med Care. 2017;55(12):1017–1022.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Human trafficking: the role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Ann Intern Med. 2016:165(8):582–588.

- Chung RJ, English A. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):427–433.

- Resources: Screening tool for victims of human trafficking. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndia/legacy/2011/10/14/health_screen_questions.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. January 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):e36–e49.

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in health-care facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:61–91.

- Geynisman-Tan JM, Taylor JS, Edersheim T, Taubel D. All the darkness we don’t see. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):135.e1–e5.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. https://humantraffickinghotline.org. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- International Labour Organization. New ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour: 20.9 million victims. http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_182109/lang--en/index.htm. Published June 2012. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. Hotline statistics. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Cone A. Report: Human trafficking in U.S. rose 35.7 percent in one year. United Press International (UPI). https://www.upi.com/Report-Human-trafficking-in-US-rose-357-percent-in-one-year/5571486328579. Published February 5, 2017. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Human trafficking. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Risk factors for and consequences of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. In Clayton E, Krugman R, Simon P, eds; Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

- Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015:135(3);566–574.

- Alpert E, Ahn R, Albright E, Purcell G, Burke T, Macias-Konstantanopoulos W. Human Trafficking: Guidebook on Identification, Assessment, and Response in the Health Care Setting. Waltham, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts Medical Society; 2014. http://www.massmed.org/Patient-Care/Health-Topics/Violence-Prevention-and-Intervention/Human-Trafficking-(pdf). Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Steele S. Human trafficking, labor brokering, and mining in southern Africa: responding to a decentralized and hidden public health disaster. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(4):665–680.

- Becker HJ, Bechtel K. Recognizing victims of human trafficking in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(2):144–147.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering postrafficking services in Europe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):55–59.

- Tracy EE, Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Identifying and assisting sexually exploited and trafficked patients seeking women’s health care services. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):443–453.

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542.

- Rafferty Y. Child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: a review of promising prevention policies and programs. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(4):559–575.

- Kiss L, Yun K, Pocock N, Zimmerman C. Exploitation, violence, and suicide risk among child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):e152278.

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, Stoklosa J. Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):23–34.

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, Shea JA. Trafficking and trauma: insight and advice for the healthcare system from sex-trafficked women incarcerated on Rikers Island. Med Care. 2017;55(12):1017–1022.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Human trafficking: the role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Ann Intern Med. 2016:165(8):582–588.

- Chung RJ, English A. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):427–433.

- Resources: Screening tool for victims of human trafficking. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndia/legacy/2011/10/14/health_screen_questions.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. January 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):e36–e49.

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in health-care facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:61–91.

- Geynisman-Tan JM, Taylor JS, Edersheim T, Taubel D. All the darkness we don’t see. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):135.e1–e5.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. https://humantraffickinghotline.org. Accessed May 30, 2018.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clues to raise suspicion

- Medical consequences of trafficking

- Screening algorithm