User login

Human trafficking: How ObGyns can—and should—be helping survivors

Despite increasing media coverage of human trafficking and the gravity of its many ramifications, I am struck by how often trainees and other clinicians present to me patients for which trafficking is a real potential concern—yet who give me a blank expression when I ask if anyone has screened these patients for being victims of trafficking. I suspect that few of us anticipated, during medical training, that we would be providing care to women who are enslaved.

How large is the problem?

It is impossible to comprehend the true scope of human trafficking. Estimates are that 20.9 million men, women, and children globally are forced into work that they are not free to leave.1

Although human trafficking is recognized as a global phenomenon, its prevalence in the United States is significant enough that it should prompt the health care community to engage in helping identify and assist victims/survivors: From January until June of 2017, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received 13,807 telephone calls, resulting in reporting of 4,460 cases.2 Indeed, from 2015 to 2016 there was a 35.7% increase in the number of hotline cases reported, for a total of 7,572 (6,340—more than 80%—of which regarded females). California had the most cases reported (1,323), followed by Texas (670) and Florida (550); those 3 states also reported an increase in trafficking crime. Vermont (5), Rhode Island (9), and Alaska (10) reported the fewest calls.3

How is trafficking defined?

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defines “trafficking in persons” as:

… recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.4

Traffickers prey on potentially vulnerable people. Girls and young women who have experienced poverty, homelessness, childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse, gender nonconformity, mental illness, or developmental delay are at particular risk.5 Children who have had interactions with Child Protective Services, come from a dysfunctional family, or have lived in a community with high crime, political or social unrest, corruption, or gender bias and discrimination are also at increased risk.6

Read about clues that raise clinical suspicion

Clues that raise clinical suspicion

A number of potential signs should make providers suspicious about potential human trafficking. Some of those signs are similar to the red flags we see in intimate partner violence, such as:

- having a difficult time talking to the patient alone

- having the accompanying person answer the patient’s questions

- body language that suggests fear, anxiety, or distrust (eg, shifting positions, looking away, appearing withdrawn)

- physical examination inconsistent with the history

- physical injury (especially multiple injuries or injuries in various stages of healing)

- refusal of interpreter services.

Trafficked girls or women may appear overly familiar with sex, have unexpected material possessions, or appear to be giving scripted or memorized answers to queries.7 Traffickers often confiscate their victims’ personal identification. They try to prevent victims from knowing their geographic locales: Patients might not have any documentation or awareness of exact surroundings (eg, their home address). Patients may be wearing clothes considered inappropriate for the weather or venue. They may have tattoos that are marks of branding.8

Medical consequences of being trafficked are obvious, numerous, and serious

Many medical sequelae that result from trafficking are obvious, given the nature of work that victims are forced to do. For example, overcrowding can lead to infectious disease, such as tuberculosis.9 Inadequate access to preventive or basic medical services can result in weight loss, poor dentition, and untreated chronic medical conditions.

If victims are experiencing physical or sexual abuse, they can present with evidence of blunt trauma, ligature marks, skin burns, wounds inflicted by weapons, and vaginal lacerations.10 A study found that 63% of survivors reported at least 10 somatic symptoms, including headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, abdominal or pelvic pain, memory loss, and symptoms of genital infectious disease.11

Girls and women being trafficked for sex may experience many of the sequelae of unprotected intercourse: irregular bleeding, unintended pregnancy, unwanted or unsafe pregnancy termination, vaginal trauma, and sexually transmitted infection (STI).12 In a study of trafficking survivors, 38% were HIV-positive.13

Trafficking survivors can suffer myriad mental health conditions, with high rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and suicidal ideation.14 A study of 387 survivors found that 12% had attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide the month before they were interviewed.15

Substance abuse is also a common problem among trafficking victims.16 One survivor interviewed in a recent study said:

It was much more difficult to work sober because I was dealing with emotions or the pain that I was feeling during intercourse, because when you have sex with people 8, 9, 10 times a day, even more than that, it starts to hurt a lot. And being high made it easier to deal with that and also it made it easier for me to get away from my body while it was happening, place my brain somewhere else.17

Because of the substantial risk of mental health problems, including substance abuse, among trafficking survivors, the physical exam of a patient should include careful assessment of demeanor and mental health status. Of course, comprehensive inspection for signs of physical or blunt trauma is paramount.

Read about Patient and staff safety during the visit

Patient and staff safety during the visit

Providers should be aware of potential safety concerns, both for the patient and for the staff. Creative strategies should be utilized to screen the patient in private. The use of interpreter services—either in person or over the telephone—should be presented and facilitated as being a routine part of practice. Any person who accompanies the patient should be asked to leave the examining room, either as a statement of practice routine or under the guise of having him (or her) step out to obtain paperwork or provide documentation.

Care of victims

Trauma-informed care should be a guiding principle for trafficking survivors. This involves empowering the patient, who may feel victimized again if asked to undress and undergo multiple physical examinations. Macias-Konstantopoulos noted: “A trauma-informed approach to care acknowledges the pervasiveness and effect of trauma across the life span of the individual, recognizes the vulnerabilities and emotional triggers of trauma survivors, minimizes repeated traumatization and fosters physical, psychological, and emotional safety, recovery, health and well-being.”18

The patient should be counseled that she has control over her body and can guide different aspects of the examination. For example the provider should discuss: 1) the amount of clothing deemed optimal for an examination, 2) the availability of a support person during the exam (for instance, a nurse or a social worker) if the patient requests one, and 3) utilization of whatever strategies the patient deems optimal for her to be most comfortable during the exam (such as leaving the door slightly ajar or having a mutually agreed-on signal to interrupt the exam).

Routine health care maintenance should be offered, including an assessment of overall physical and dental health and screening for STI and mental health. Screening for substances of abuse should be considered. If indicated, emergency contraception, postexposure HIV prophylaxis, immunizations, and empiric antibiotics for STI should be offered.19

Screening when indicated by evidence, suspicion, or concern

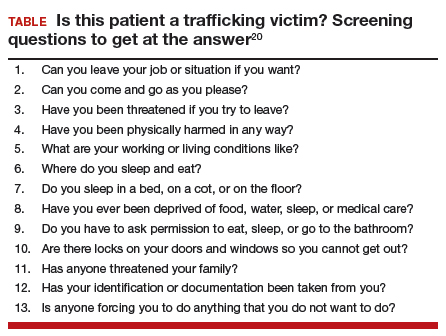

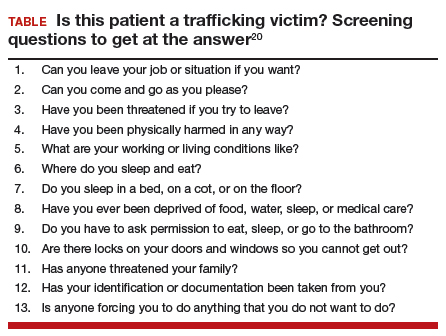

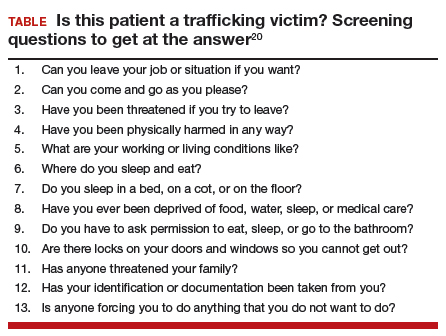

Unlike the case with intimate partner violence, experts do not recommend universal screening for human trafficking. Clinicians should be comfortable, however, trying to elicit that history when a concern arises, either because of identified risk factors, red flags, or concerns that arise from the findings of the history or physical. Ideally, clinicians should consider becoming comfortable choosing a few screening questions to regularly incorporate into their assessment. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) offers a list of questions that can be utilized (TABLE).20

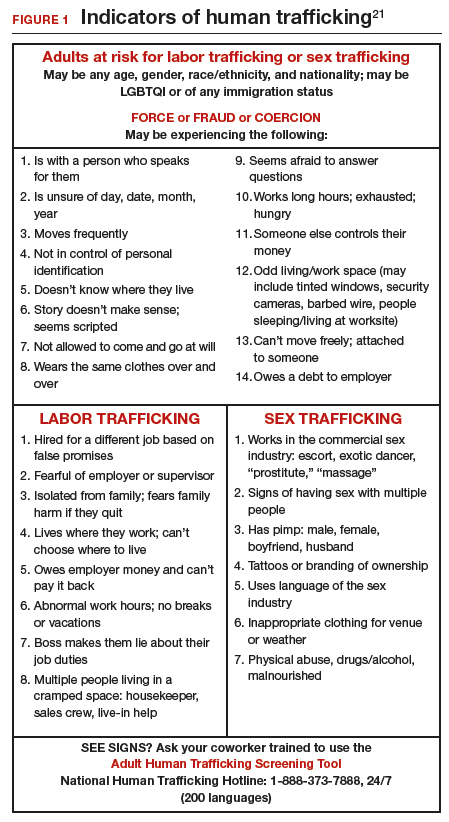

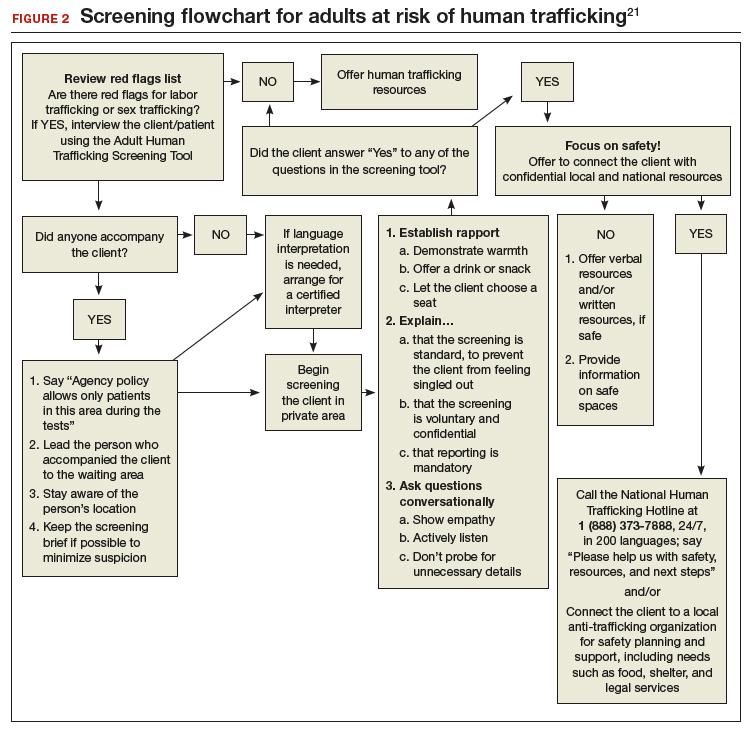

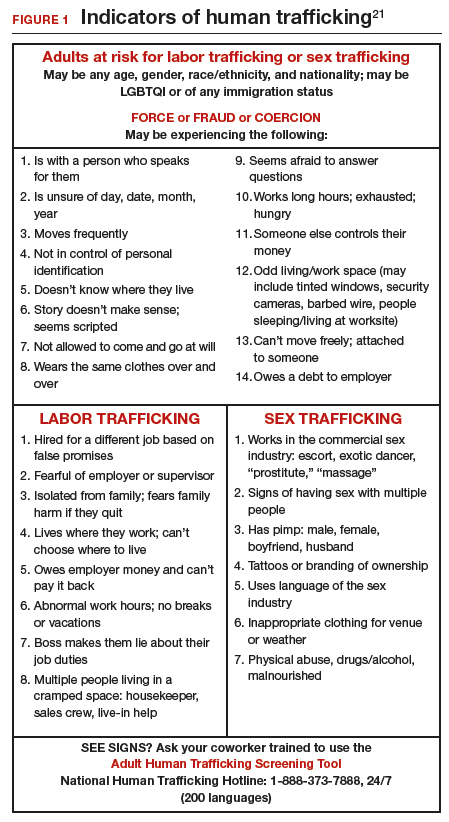

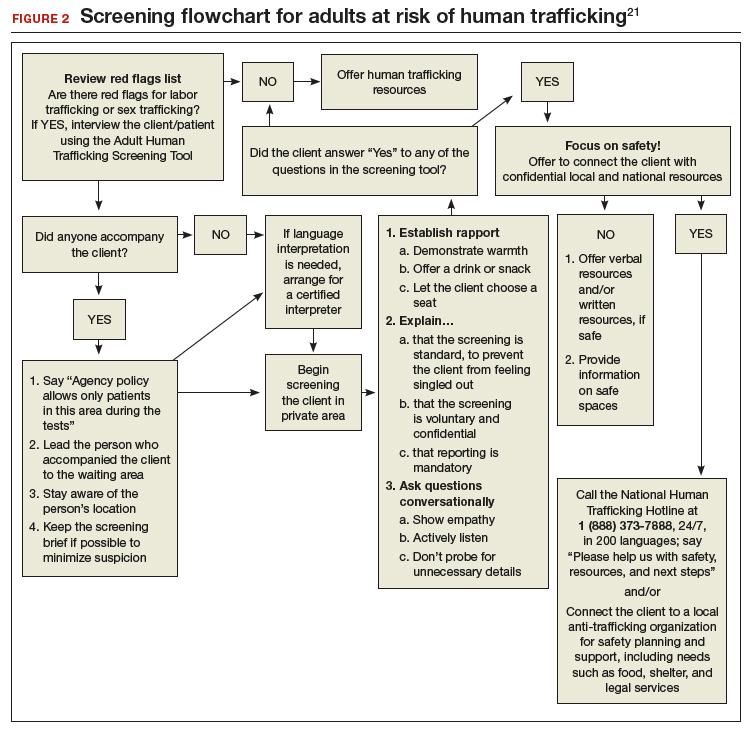

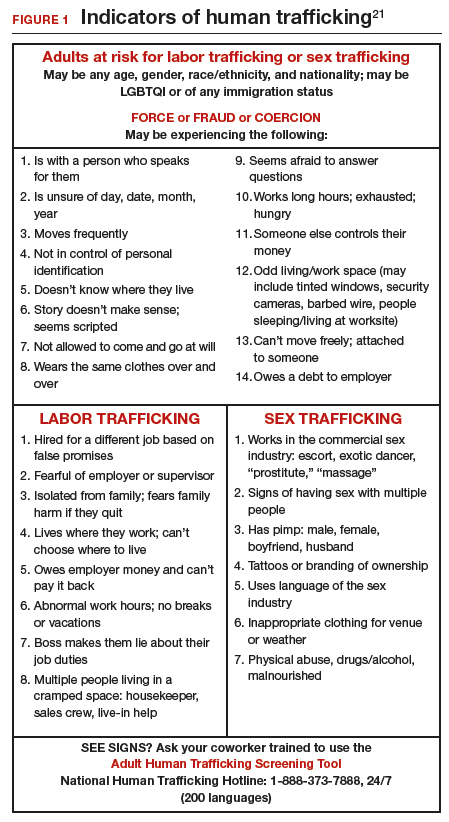

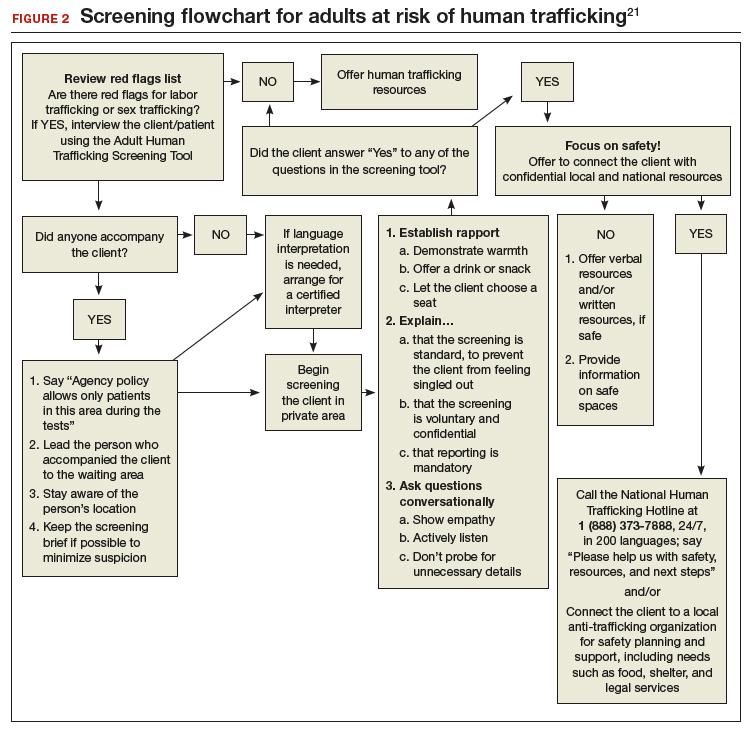

In January 2018, the Office on Trafficking in Persons, a unit of the HHS Administration for Children and Families, released an “Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide.” The document includes 2 excellent tools21 that clinicians can utilize to identify patients who should be screened and how to identify and assist survivors (FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2).

Clinicians, in their encounters with patients, are particularly well-positioned to intersect with, and identify, survivors. Regrettably, such opportunities are often missed—and victims thus remain unidentified and trapped in their circumstances. A study revealed that one-half of survivors who were interviewed reported seeing a physician while they were being trafficked.22 Even more alarming, another study showed that 87.8% of survivors had received health care during their captivity.23 It is dismaying to know that these patients left those health care settings without receiving the assistance they truly need and with their true circumstances remaining unidentified.

Read about Finding assistance and support

Finding assistance and support

Centers in the United States now provide trauma-informed care for trafficking survivors in a confidential setting (see “Specialized care is increasingly available”).24 A physician who works at a center in New York City noted: “Our survivors told us that more than fear or pain, the feelings that sat with them most often were worthlessness and invisibility. We can do better as physicians and as educators to expose this epidemic and care for its victims.”24

Here is a sampling of the growing number of centers in the United States that provide trauma-centered care for survivors of human trafficking:

- Survivor Clinic at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

- EMPOWER Clinic for Survivors of Sex Trafficking and Sexual Violence at NYU Langone Health, New York, New York

- Freedom Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- The Hope Through Health Clinic, Austin, Texas

- Pacific Survivor Center, Honolulu, Hawaii

Most clinicians practice in settings that do not have easy access to such subspecialized centers, however. For them, the National Human Trafficking Hotline can be an invaluable resource (see “Hotline is a valuable resource”).25 Law enforcement and social services colleagues also can be useful allies.

Uncertain how you can help a patient who is a victim of human trafficking? For assistance and support, contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline--24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and in 200 languages--in any of 3 ways:

- By telephone: (888) 373-7888

- By text: 233733

- On the web: https://humantraffickinghotline.orga

aIncludes a search field that clinicians can use to look up the nearest resources for additional assistance.

Let’s turn our concern and awareness into results

We, as providers of women’s health care, are uniquely positioned to help these most vulnerable of people, many of whom have been stripped of personal documents and denied access to financial resources and community support. As a medical community, we should strive to combat this tragic epidemic, 1 patient at a time.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- International Labour Organization. New ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour: 20.9 million victims. http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_182109/lang--en/index.htm. Published June 2012. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. Hotline statistics. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Cone A. Report: Human trafficking in U.S. rose 35.7 percent in one year. United Press International (UPI). https://www.upi.com/Report-Human-trafficking-in-US-rose-357-percent-in-one-year/5571486328579. Published February 5, 2017. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Human trafficking. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Risk factors for and consequences of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. In Clayton E, Krugman R, Simon P, eds; Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

- Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015:135(3);566–574.

- Alpert E, Ahn R, Albright E, Purcell G, Burke T, Macias-Konstantanopoulos W. Human Trafficking: Guidebook on Identification, Assessment, and Response in the Health Care Setting. Waltham, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts Medical Society; 2014. http://www.massmed.org/Patient-Care/Health-Topics/Violence-Prevention-and-Intervention/Human-Trafficking-(pdf). Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Steele S. Human trafficking, labor brokering, and mining in southern Africa: responding to a decentralized and hidden public health disaster. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(4):665–680.

- Becker HJ, Bechtel K. Recognizing victims of human trafficking in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(2):144–147.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering postrafficking services in Europe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):55–59.

- Tracy EE, Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Identifying and assisting sexually exploited and trafficked patients seeking women’s health care services. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):443–453.

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542.

- Rafferty Y. Child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: a review of promising prevention policies and programs. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(4):559–575.

- Kiss L, Yun K, Pocock N, Zimmerman C. Exploitation, violence, and suicide risk among child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):e152278.

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, Stoklosa J. Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):23–34.

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, Shea JA. Trafficking and trauma: insight and advice for the healthcare system from sex-trafficked women incarcerated on Rikers Island. Med Care. 2017;55(12):1017–1022.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Human trafficking: the role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Ann Intern Med. 2016:165(8):582–588.

- Chung RJ, English A. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):427–433.

- Resources: Screening tool for victims of human trafficking. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndia/legacy/2011/10/14/health_screen_questions.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. January 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):e36–e49.

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in health-care facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:61–91.

- Geynisman-Tan JM, Taylor JS, Edersheim T, Taubel D. All the darkness we don’t see. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):135.e1–e5.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. https://humantraffickinghotline.org. Accessed May 30, 2018.

Despite increasing media coverage of human trafficking and the gravity of its many ramifications, I am struck by how often trainees and other clinicians present to me patients for which trafficking is a real potential concern—yet who give me a blank expression when I ask if anyone has screened these patients for being victims of trafficking. I suspect that few of us anticipated, during medical training, that we would be providing care to women who are enslaved.

How large is the problem?

It is impossible to comprehend the true scope of human trafficking. Estimates are that 20.9 million men, women, and children globally are forced into work that they are not free to leave.1

Although human trafficking is recognized as a global phenomenon, its prevalence in the United States is significant enough that it should prompt the health care community to engage in helping identify and assist victims/survivors: From January until June of 2017, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received 13,807 telephone calls, resulting in reporting of 4,460 cases.2 Indeed, from 2015 to 2016 there was a 35.7% increase in the number of hotline cases reported, for a total of 7,572 (6,340—more than 80%—of which regarded females). California had the most cases reported (1,323), followed by Texas (670) and Florida (550); those 3 states also reported an increase in trafficking crime. Vermont (5), Rhode Island (9), and Alaska (10) reported the fewest calls.3

How is trafficking defined?

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defines “trafficking in persons” as:

… recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.4

Traffickers prey on potentially vulnerable people. Girls and young women who have experienced poverty, homelessness, childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse, gender nonconformity, mental illness, or developmental delay are at particular risk.5 Children who have had interactions with Child Protective Services, come from a dysfunctional family, or have lived in a community with high crime, political or social unrest, corruption, or gender bias and discrimination are also at increased risk.6

Read about clues that raise clinical suspicion

Clues that raise clinical suspicion

A number of potential signs should make providers suspicious about potential human trafficking. Some of those signs are similar to the red flags we see in intimate partner violence, such as:

- having a difficult time talking to the patient alone

- having the accompanying person answer the patient’s questions

- body language that suggests fear, anxiety, or distrust (eg, shifting positions, looking away, appearing withdrawn)

- physical examination inconsistent with the history

- physical injury (especially multiple injuries or injuries in various stages of healing)

- refusal of interpreter services.

Trafficked girls or women may appear overly familiar with sex, have unexpected material possessions, or appear to be giving scripted or memorized answers to queries.7 Traffickers often confiscate their victims’ personal identification. They try to prevent victims from knowing their geographic locales: Patients might not have any documentation or awareness of exact surroundings (eg, their home address). Patients may be wearing clothes considered inappropriate for the weather or venue. They may have tattoos that are marks of branding.8

Medical consequences of being trafficked are obvious, numerous, and serious

Many medical sequelae that result from trafficking are obvious, given the nature of work that victims are forced to do. For example, overcrowding can lead to infectious disease, such as tuberculosis.9 Inadequate access to preventive or basic medical services can result in weight loss, poor dentition, and untreated chronic medical conditions.

If victims are experiencing physical or sexual abuse, they can present with evidence of blunt trauma, ligature marks, skin burns, wounds inflicted by weapons, and vaginal lacerations.10 A study found that 63% of survivors reported at least 10 somatic symptoms, including headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, abdominal or pelvic pain, memory loss, and symptoms of genital infectious disease.11

Girls and women being trafficked for sex may experience many of the sequelae of unprotected intercourse: irregular bleeding, unintended pregnancy, unwanted or unsafe pregnancy termination, vaginal trauma, and sexually transmitted infection (STI).12 In a study of trafficking survivors, 38% were HIV-positive.13

Trafficking survivors can suffer myriad mental health conditions, with high rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and suicidal ideation.14 A study of 387 survivors found that 12% had attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide the month before they were interviewed.15

Substance abuse is also a common problem among trafficking victims.16 One survivor interviewed in a recent study said:

It was much more difficult to work sober because I was dealing with emotions or the pain that I was feeling during intercourse, because when you have sex with people 8, 9, 10 times a day, even more than that, it starts to hurt a lot. And being high made it easier to deal with that and also it made it easier for me to get away from my body while it was happening, place my brain somewhere else.17

Because of the substantial risk of mental health problems, including substance abuse, among trafficking survivors, the physical exam of a patient should include careful assessment of demeanor and mental health status. Of course, comprehensive inspection for signs of physical or blunt trauma is paramount.

Read about Patient and staff safety during the visit

Patient and staff safety during the visit

Providers should be aware of potential safety concerns, both for the patient and for the staff. Creative strategies should be utilized to screen the patient in private. The use of interpreter services—either in person or over the telephone—should be presented and facilitated as being a routine part of practice. Any person who accompanies the patient should be asked to leave the examining room, either as a statement of practice routine or under the guise of having him (or her) step out to obtain paperwork or provide documentation.

Care of victims

Trauma-informed care should be a guiding principle for trafficking survivors. This involves empowering the patient, who may feel victimized again if asked to undress and undergo multiple physical examinations. Macias-Konstantopoulos noted: “A trauma-informed approach to care acknowledges the pervasiveness and effect of trauma across the life span of the individual, recognizes the vulnerabilities and emotional triggers of trauma survivors, minimizes repeated traumatization and fosters physical, psychological, and emotional safety, recovery, health and well-being.”18

The patient should be counseled that she has control over her body and can guide different aspects of the examination. For example the provider should discuss: 1) the amount of clothing deemed optimal for an examination, 2) the availability of a support person during the exam (for instance, a nurse or a social worker) if the patient requests one, and 3) utilization of whatever strategies the patient deems optimal for her to be most comfortable during the exam (such as leaving the door slightly ajar or having a mutually agreed-on signal to interrupt the exam).

Routine health care maintenance should be offered, including an assessment of overall physical and dental health and screening for STI and mental health. Screening for substances of abuse should be considered. If indicated, emergency contraception, postexposure HIV prophylaxis, immunizations, and empiric antibiotics for STI should be offered.19

Screening when indicated by evidence, suspicion, or concern

Unlike the case with intimate partner violence, experts do not recommend universal screening for human trafficking. Clinicians should be comfortable, however, trying to elicit that history when a concern arises, either because of identified risk factors, red flags, or concerns that arise from the findings of the history or physical. Ideally, clinicians should consider becoming comfortable choosing a few screening questions to regularly incorporate into their assessment. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) offers a list of questions that can be utilized (TABLE).20

In January 2018, the Office on Trafficking in Persons, a unit of the HHS Administration for Children and Families, released an “Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide.” The document includes 2 excellent tools21 that clinicians can utilize to identify patients who should be screened and how to identify and assist survivors (FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2).

Clinicians, in their encounters with patients, are particularly well-positioned to intersect with, and identify, survivors. Regrettably, such opportunities are often missed—and victims thus remain unidentified and trapped in their circumstances. A study revealed that one-half of survivors who were interviewed reported seeing a physician while they were being trafficked.22 Even more alarming, another study showed that 87.8% of survivors had received health care during their captivity.23 It is dismaying to know that these patients left those health care settings without receiving the assistance they truly need and with their true circumstances remaining unidentified.

Read about Finding assistance and support

Finding assistance and support

Centers in the United States now provide trauma-informed care for trafficking survivors in a confidential setting (see “Specialized care is increasingly available”).24 A physician who works at a center in New York City noted: “Our survivors told us that more than fear or pain, the feelings that sat with them most often were worthlessness and invisibility. We can do better as physicians and as educators to expose this epidemic and care for its victims.”24

Here is a sampling of the growing number of centers in the United States that provide trauma-centered care for survivors of human trafficking:

- Survivor Clinic at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

- EMPOWER Clinic for Survivors of Sex Trafficking and Sexual Violence at NYU Langone Health, New York, New York

- Freedom Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- The Hope Through Health Clinic, Austin, Texas

- Pacific Survivor Center, Honolulu, Hawaii

Most clinicians practice in settings that do not have easy access to such subspecialized centers, however. For them, the National Human Trafficking Hotline can be an invaluable resource (see “Hotline is a valuable resource”).25 Law enforcement and social services colleagues also can be useful allies.

Uncertain how you can help a patient who is a victim of human trafficking? For assistance and support, contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline--24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and in 200 languages--in any of 3 ways:

- By telephone: (888) 373-7888

- By text: 233733

- On the web: https://humantraffickinghotline.orga

aIncludes a search field that clinicians can use to look up the nearest resources for additional assistance.

Let’s turn our concern and awareness into results

We, as providers of women’s health care, are uniquely positioned to help these most vulnerable of people, many of whom have been stripped of personal documents and denied access to financial resources and community support. As a medical community, we should strive to combat this tragic epidemic, 1 patient at a time.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Despite increasing media coverage of human trafficking and the gravity of its many ramifications, I am struck by how often trainees and other clinicians present to me patients for which trafficking is a real potential concern—yet who give me a blank expression when I ask if anyone has screened these patients for being victims of trafficking. I suspect that few of us anticipated, during medical training, that we would be providing care to women who are enslaved.

How large is the problem?

It is impossible to comprehend the true scope of human trafficking. Estimates are that 20.9 million men, women, and children globally are forced into work that they are not free to leave.1

Although human trafficking is recognized as a global phenomenon, its prevalence in the United States is significant enough that it should prompt the health care community to engage in helping identify and assist victims/survivors: From January until June of 2017, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received 13,807 telephone calls, resulting in reporting of 4,460 cases.2 Indeed, from 2015 to 2016 there was a 35.7% increase in the number of hotline cases reported, for a total of 7,572 (6,340—more than 80%—of which regarded females). California had the most cases reported (1,323), followed by Texas (670) and Florida (550); those 3 states also reported an increase in trafficking crime. Vermont (5), Rhode Island (9), and Alaska (10) reported the fewest calls.3

How is trafficking defined?

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime defines “trafficking in persons” as:

… recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.4

Traffickers prey on potentially vulnerable people. Girls and young women who have experienced poverty, homelessness, childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse, gender nonconformity, mental illness, or developmental delay are at particular risk.5 Children who have had interactions with Child Protective Services, come from a dysfunctional family, or have lived in a community with high crime, political or social unrest, corruption, or gender bias and discrimination are also at increased risk.6

Read about clues that raise clinical suspicion

Clues that raise clinical suspicion

A number of potential signs should make providers suspicious about potential human trafficking. Some of those signs are similar to the red flags we see in intimate partner violence, such as:

- having a difficult time talking to the patient alone

- having the accompanying person answer the patient’s questions

- body language that suggests fear, anxiety, or distrust (eg, shifting positions, looking away, appearing withdrawn)

- physical examination inconsistent with the history

- physical injury (especially multiple injuries or injuries in various stages of healing)

- refusal of interpreter services.

Trafficked girls or women may appear overly familiar with sex, have unexpected material possessions, or appear to be giving scripted or memorized answers to queries.7 Traffickers often confiscate their victims’ personal identification. They try to prevent victims from knowing their geographic locales: Patients might not have any documentation or awareness of exact surroundings (eg, their home address). Patients may be wearing clothes considered inappropriate for the weather or venue. They may have tattoos that are marks of branding.8

Medical consequences of being trafficked are obvious, numerous, and serious

Many medical sequelae that result from trafficking are obvious, given the nature of work that victims are forced to do. For example, overcrowding can lead to infectious disease, such as tuberculosis.9 Inadequate access to preventive or basic medical services can result in weight loss, poor dentition, and untreated chronic medical conditions.

If victims are experiencing physical or sexual abuse, they can present with evidence of blunt trauma, ligature marks, skin burns, wounds inflicted by weapons, and vaginal lacerations.10 A study found that 63% of survivors reported at least 10 somatic symptoms, including headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, abdominal or pelvic pain, memory loss, and symptoms of genital infectious disease.11

Girls and women being trafficked for sex may experience many of the sequelae of unprotected intercourse: irregular bleeding, unintended pregnancy, unwanted or unsafe pregnancy termination, vaginal trauma, and sexually transmitted infection (STI).12 In a study of trafficking survivors, 38% were HIV-positive.13

Trafficking survivors can suffer myriad mental health conditions, with high rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and suicidal ideation.14 A study of 387 survivors found that 12% had attempted to harm themselves or commit suicide the month before they were interviewed.15

Substance abuse is also a common problem among trafficking victims.16 One survivor interviewed in a recent study said:

It was much more difficult to work sober because I was dealing with emotions or the pain that I was feeling during intercourse, because when you have sex with people 8, 9, 10 times a day, even more than that, it starts to hurt a lot. And being high made it easier to deal with that and also it made it easier for me to get away from my body while it was happening, place my brain somewhere else.17

Because of the substantial risk of mental health problems, including substance abuse, among trafficking survivors, the physical exam of a patient should include careful assessment of demeanor and mental health status. Of course, comprehensive inspection for signs of physical or blunt trauma is paramount.

Read about Patient and staff safety during the visit

Patient and staff safety during the visit

Providers should be aware of potential safety concerns, both for the patient and for the staff. Creative strategies should be utilized to screen the patient in private. The use of interpreter services—either in person or over the telephone—should be presented and facilitated as being a routine part of practice. Any person who accompanies the patient should be asked to leave the examining room, either as a statement of practice routine or under the guise of having him (or her) step out to obtain paperwork or provide documentation.

Care of victims

Trauma-informed care should be a guiding principle for trafficking survivors. This involves empowering the patient, who may feel victimized again if asked to undress and undergo multiple physical examinations. Macias-Konstantopoulos noted: “A trauma-informed approach to care acknowledges the pervasiveness and effect of trauma across the life span of the individual, recognizes the vulnerabilities and emotional triggers of trauma survivors, minimizes repeated traumatization and fosters physical, psychological, and emotional safety, recovery, health and well-being.”18

The patient should be counseled that she has control over her body and can guide different aspects of the examination. For example the provider should discuss: 1) the amount of clothing deemed optimal for an examination, 2) the availability of a support person during the exam (for instance, a nurse or a social worker) if the patient requests one, and 3) utilization of whatever strategies the patient deems optimal for her to be most comfortable during the exam (such as leaving the door slightly ajar or having a mutually agreed-on signal to interrupt the exam).

Routine health care maintenance should be offered, including an assessment of overall physical and dental health and screening for STI and mental health. Screening for substances of abuse should be considered. If indicated, emergency contraception, postexposure HIV prophylaxis, immunizations, and empiric antibiotics for STI should be offered.19

Screening when indicated by evidence, suspicion, or concern

Unlike the case with intimate partner violence, experts do not recommend universal screening for human trafficking. Clinicians should be comfortable, however, trying to elicit that history when a concern arises, either because of identified risk factors, red flags, or concerns that arise from the findings of the history or physical. Ideally, clinicians should consider becoming comfortable choosing a few screening questions to regularly incorporate into their assessment. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) offers a list of questions that can be utilized (TABLE).20

In January 2018, the Office on Trafficking in Persons, a unit of the HHS Administration for Children and Families, released an “Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide.” The document includes 2 excellent tools21 that clinicians can utilize to identify patients who should be screened and how to identify and assist survivors (FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2).

Clinicians, in their encounters with patients, are particularly well-positioned to intersect with, and identify, survivors. Regrettably, such opportunities are often missed—and victims thus remain unidentified and trapped in their circumstances. A study revealed that one-half of survivors who were interviewed reported seeing a physician while they were being trafficked.22 Even more alarming, another study showed that 87.8% of survivors had received health care during their captivity.23 It is dismaying to know that these patients left those health care settings without receiving the assistance they truly need and with their true circumstances remaining unidentified.

Read about Finding assistance and support

Finding assistance and support

Centers in the United States now provide trauma-informed care for trafficking survivors in a confidential setting (see “Specialized care is increasingly available”).24 A physician who works at a center in New York City noted: “Our survivors told us that more than fear or pain, the feelings that sat with them most often were worthlessness and invisibility. We can do better as physicians and as educators to expose this epidemic and care for its victims.”24

Here is a sampling of the growing number of centers in the United States that provide trauma-centered care for survivors of human trafficking:

- Survivor Clinic at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

- EMPOWER Clinic for Survivors of Sex Trafficking and Sexual Violence at NYU Langone Health, New York, New York

- Freedom Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- The Hope Through Health Clinic, Austin, Texas

- Pacific Survivor Center, Honolulu, Hawaii

Most clinicians practice in settings that do not have easy access to such subspecialized centers, however. For them, the National Human Trafficking Hotline can be an invaluable resource (see “Hotline is a valuable resource”).25 Law enforcement and social services colleagues also can be useful allies.

Uncertain how you can help a patient who is a victim of human trafficking? For assistance and support, contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline--24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and in 200 languages--in any of 3 ways:

- By telephone: (888) 373-7888

- By text: 233733

- On the web: https://humantraffickinghotline.orga

aIncludes a search field that clinicians can use to look up the nearest resources for additional assistance.

Let’s turn our concern and awareness into results

We, as providers of women’s health care, are uniquely positioned to help these most vulnerable of people, many of whom have been stripped of personal documents and denied access to financial resources and community support. As a medical community, we should strive to combat this tragic epidemic, 1 patient at a time.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- International Labour Organization. New ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour: 20.9 million victims. http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_182109/lang--en/index.htm. Published June 2012. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. Hotline statistics. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Cone A. Report: Human trafficking in U.S. rose 35.7 percent in one year. United Press International (UPI). https://www.upi.com/Report-Human-trafficking-in-US-rose-357-percent-in-one-year/5571486328579. Published February 5, 2017. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Human trafficking. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Risk factors for and consequences of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. In Clayton E, Krugman R, Simon P, eds; Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

- Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015:135(3);566–574.

- Alpert E, Ahn R, Albright E, Purcell G, Burke T, Macias-Konstantanopoulos W. Human Trafficking: Guidebook on Identification, Assessment, and Response in the Health Care Setting. Waltham, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts Medical Society; 2014. http://www.massmed.org/Patient-Care/Health-Topics/Violence-Prevention-and-Intervention/Human-Trafficking-(pdf). Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Steele S. Human trafficking, labor brokering, and mining in southern Africa: responding to a decentralized and hidden public health disaster. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(4):665–680.

- Becker HJ, Bechtel K. Recognizing victims of human trafficking in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(2):144–147.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering postrafficking services in Europe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):55–59.

- Tracy EE, Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Identifying and assisting sexually exploited and trafficked patients seeking women’s health care services. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):443–453.

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542.

- Rafferty Y. Child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: a review of promising prevention policies and programs. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(4):559–575.

- Kiss L, Yun K, Pocock N, Zimmerman C. Exploitation, violence, and suicide risk among child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):e152278.

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, Stoklosa J. Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):23–34.

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, Shea JA. Trafficking and trauma: insight and advice for the healthcare system from sex-trafficked women incarcerated on Rikers Island. Med Care. 2017;55(12):1017–1022.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Human trafficking: the role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Ann Intern Med. 2016:165(8):582–588.

- Chung RJ, English A. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):427–433.

- Resources: Screening tool for victims of human trafficking. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndia/legacy/2011/10/14/health_screen_questions.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. January 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):e36–e49.

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in health-care facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:61–91.

- Geynisman-Tan JM, Taylor JS, Edersheim T, Taubel D. All the darkness we don’t see. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):135.e1–e5.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. https://humantraffickinghotline.org. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- International Labour Organization. New ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour: 20.9 million victims. http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_182109/lang--en/index.htm. Published June 2012. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. Hotline statistics. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Cone A. Report: Human trafficking in U.S. rose 35.7 percent in one year. United Press International (UPI). https://www.upi.com/Report-Human-trafficking-in-US-rose-357-percent-in-one-year/5571486328579. Published February 5, 2017. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Human trafficking. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Risk factors for and consequences of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. In Clayton E, Krugman R, Simon P, eds; Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

- Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015:135(3);566–574.

- Alpert E, Ahn R, Albright E, Purcell G, Burke T, Macias-Konstantanopoulos W. Human Trafficking: Guidebook on Identification, Assessment, and Response in the Health Care Setting. Waltham, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts Medical Society; 2014. http://www.massmed.org/Patient-Care/Health-Topics/Violence-Prevention-and-Intervention/Human-Trafficking-(pdf). Accessed May 30, 2018.

- National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Steele S. Human trafficking, labor brokering, and mining in southern Africa: responding to a decentralized and hidden public health disaster. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(4):665–680.

- Becker HJ, Bechtel K. Recognizing victims of human trafficking in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(2):144–147.

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering postrafficking services in Europe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):55–59.

- Tracy EE, Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Identifying and assisting sexually exploited and trafficked patients seeking women’s health care services. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):443–453.

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298(5):536–542.

- Rafferty Y. Child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: a review of promising prevention policies and programs. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(4):559–575.

- Kiss L, Yun K, Pocock N, Zimmerman C. Exploitation, violence, and suicide risk among child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):e152278.

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, Stoklosa J. Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):23–34.

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, Shea JA. Trafficking and trauma: insight and advice for the healthcare system from sex-trafficked women incarcerated on Rikers Island. Med Care. 2017;55(12):1017–1022.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos W. Human trafficking: the role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Ann Intern Med. 2016:165(8):582–588.

- Chung RJ, English A. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):427–433.

- Resources: Screening tool for victims of human trafficking. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndia/legacy/2011/10/14/health_screen_questions.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. January 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):e36–e49.

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in health-care facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:61–91.

- Geynisman-Tan JM, Taylor JS, Edersheim T, Taubel D. All the darkness we don’t see. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):135.e1–e5.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline. https://humantraffickinghotline.org. Accessed May 30, 2018.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clues to raise suspicion

- Medical consequences of trafficking

- Screening algorithm

Alcohol: An unfortunate teratogen

Medical students learn early in their education that alcohol is a teratogen. Despite this widespread knowledge, many obstetricians counsel patients about the safety of low doses of alcohol in pregnancy.1 Indeed, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ position on this is, “while the safest approach may be to avoid any alcohol during pregnancy, it remains the case that there is no evidence of harm from low levels of alcohol consumption, defined as no more than one or two units of alcohol once or twice a week.”2

Like many providers, I was aware of this controversy, but it became truly personal when a beloved family member was diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). In this paper, I will review some of the controversy regarding alcohol in pregnancy, highlight findings from the literature, provide tools for prevention, and identify new developments regarding this devastating, preventable condition.

Charlie

To know my nephew Charlie is to fall in love with my nephew Charlie. One of the happiest moments of my life was when I learned my brother and sister-in-law had adopted twins from Kazakhstan. When my little niece and nephew started their new life in the United States, certain medical issues seemed to merit additional attention. Although both were very small for their age and required significant nutritional support, Charlie seemed to be a bit more rambunctious and required additional supervision.

The children were fortunate enough to have incredibly loving, dedicated parents, who have access to exceptional medical care as residents of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After extensive testing, it became clear what was causing Charlie’s developmental delay; his pediatric team made the diagnosis of FAS. My brother and sister-in-law became incredibly well-read about this challenging disorder, and threw themselves into national advocacy work to help prevent this unnecessary tragedy.

Recent data point to teratogenicity, but media confuse the issue

Some recent media coverage3 of celebrities who apparently drank while pregnant was in response to an article in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.4 The authors of this study concluded that, “at age 5 years, cohort members born to mothers who drank up to one to two drinks per week or per occasion during pregnancy were not at increased risk of clinically relevant behavioral difficulties or cognitive deficits, compared with children of mothers in the not-in-pregnancy group.”

This is certainly not the first occasion the popular press has covered a published study that seems to indicate no ill effects of alcohol use in pregnancy. A 2008 report by Kelly and colleagues,5 and its subsequent media coverage, prompted the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Study Group to state that the panel of experts was “alarmed” by recent newspaper reports suggesting that light drinking during pregnancy may be beneficial for an unborn child.6 They noted misleading and irresponsible media reports of the findings, which suggested that 3-year-old children whose mothers drank “lightly” during pregnancy were not at risk for certain behavioral problems.

What the study authors proceeded to note, however (that the media did not mention), was that the light drinkers in their study had socioeconomic advantages, compared with nondrinkers.5 (Advantaged economic status is established to be beneficial for childhood development.) They also noted that the study involved preschool-aged children, stating “Generally the adverse effects of light drinking during pregnancy are subtle and may go undetected in young children. However, other group studies of more moderate or ‘social’ drinking levels during pregnancy have shown an adverse impact on multiple aspects of development through adolescence and young adulthood, even when important environmental factors are taken into account.” A sentence I thought was most compelling in their statement was, “It is an inconvenient fact of life that alcohol is a teratogen.” Now, this fact is well supported in the literature.7

There are animal studies regarding the use of “low-dose” or “moderate” alcohol in pregnancy that demonstrate adverse behavioral outcomes with exposure to even small doses of alcohol.8,9 It is an American tragedy that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), rates of FAS in this country range from 0.2 to 2.0 cases per 1,000 live births. Indeed, the rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) might be at least three times this rate.10 As is the case with other disorders, there are health disparities regarding the prevalence of this condition as well.11

FAS: A long history of preventable disease

1973: Identified. FAS was first described in a 1973 Lancet report, “Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers.”12

1996: Call for prevention. In 1995, the US Surgeon General issued a statement regarding alcohol use in pregnancy, noting, “We do not know what, if any, amount of alcohol is safe.”13 In 1996, the Institute of Medicine released a paper calling FAS and FASD “completely preventable birth defects and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.”14

2000: The troubling effects gathered. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a monograph on FAS in 2000, defining it as a constellation of physical, behavioral, and cognitive abnormalities.15

These features classically define FAS:

- dysmorphic facial features

- prenatal and postnatal growth abnormalities

- mental retardation.

Approximately 80% of children with this condition have:

- microcephaly

- behavioral abnormalities.

As many as 50% of affected children also exhibit:

- poor coordination

- hypotonia

- attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- decreased adipose tissue

- identifiable facial anomalies (such as maxillary hypoplasia, cleft palate, and micrognathia).

Also common:

- cardiac defects

- hemangiomas

- eye or ear abnormalities.

The AAP further noted that data current to the time (and still true today) did not support the concept of a safe level of alcohol consumption by pregnant women below which no damage to a fetus will occur.15

Alcohol intake during pregnancy puts the fetus at risk for cognitive and neuropsychological impairment and physical abnormalities, including dysmorphic facial features (such as micrognathia), restricted prenatal growth, cardiac defects, and eye and ear abnormalities. There is no threshold dose of alcohol that is safe during pregnancy, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Despite the knowledge we’ve gained, FAS persists

According to a 2006–2010 CDC analysis involving more than 345,000 women of reproductive age from all 50 states, 7.6% of pregnant women reported alcohol use and 1.4% (or 1 in 71) reported binge drinking (defined, respectively, as at least one alcoholic drink and four or more alcoholic drinks on one occasion in the past 30 days).16 The highest prevalence of obstetric alcohol consumption occurs in women who are:

- aged 35 to 44 years

- white

- college graduates

- employed.

The problem may be bigger than reported. The incidences of alcohol and binge drinking found in the CDC report include women’s self-report—but women drink alcohol without knowing they’re pregnant. Only 40% of women realize they’re pregnant at 4 weeks of gestation, a critical time for organogenesis, and approximately half of all births are unplanned.9

When my brother and sister-in law adopted my beautiful niece and nephew, they were very aware of the risk for conditions like FAS. In an evaluation of 71 children adopted from Eastern Europe at 5 years of age, FAS was diagnosed in 30% of children and “partial FAS” in another 9%.17 Birth defects attributed to alcohol were present in 11% of the children.

Are women’s health providers up to date on FAS education?

In recognition of alcohol’s potentially life-altering consequences for the developing fetus, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) produced an FASD prevention tool kit in 2006 and published a 2011 committee opinion on at-risk drinking and alcohol dependence and their implications for obstetrics and gynecology.18,19 Both guidelines direct clinicians to advise patients to abstain from alcohol during pregnancy.

Results from a 2010 survey of 800 ACOG fellows revealed that only 78% of obstetricians advised abstinence from alcohol during pregnancy. Fifty-eight percent of respondents did not use a validated screening tool for alcohol use in their pregnant patients, and only 72% felt prepared to screen for risky or hazardous drinking.19 (Most were unaware of the ACOG tool kit, which had been published several years earlier.)

In a survey of pediatricians, obstetricians, and family physicians, clinicians said that about 67% of their patients asked about alcohol use in pregnancy, with about 2% of those patients specifically mentioning FAS. About 41% of these same physicians erroneously placed the threshold for FAS at one to three drinks per day,20 when in fact there is no threshold of drinking that has been proven to be safe.

A survey of 1,000 actively practicing ACOG fellows revealed that, while 97% of obstetricians routinely asked their patients about alcohol use, only 20% of providers reported to their patients that abstinence was safest, and 4% of providers didn’t believe that consumption of eight or more drinks weekly posed fetal risk.21

How can we educate our patients about the dangers of alcohol in pregnancy?

Fetal death. A recent Danish study of 79,216 pregnant women revealed that 45% had consumed some alcohol during pregnancy. Two percent reported at least four drinks per week, and 25% admitted to binge drinking during pregnancy. Term infants born to women in the latter two groups had increased neonatal mortality, with hazard ratios of 3.56 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15–8.43) and 2.69 (95% CI, 1.27–5.69), respectively.22

Decreased cognitive status. A study by Willford and colleagues evaluated the relationship between prenatal alcohol exposure and cognitive status of 1,360 10-year-old children.23 The authors utilized the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test, including the composite scores and verbal, abstract/visual, quantitative, and short-term memory scores. After controlling for other variables, among African American offspring they found that, for each additional drink, the average composite score decreased by 1.9 points. This difference was more striking for second-trimester use, and was significant even for one drink daily versus abstention from alcohol.

Impaired neuropsychological development. Another study evaluating light to moderate amounts of prenatal alcohol exposure in 10- and 11-year-old children found significantly worse scores regarding a number of neuropsychological developmental assessments.24

No threshold dose of causation. Results of a 2012 prospective study in California, with data collected on 992 subjects from 1978 until 2005, revealed that many physical FAS features, including microcephaly, smooth philtrum, and thin vermillion border; reduced birth length; and reduced birth weight, were associated with alcohol exposure at specific gestational ages, and were dose-related.25 This paper didn’t reveal any evidence of a threshold dose of causation.

Neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS are not always considered

Another recent study that the media recently highlighted as finding “no association between low or moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and birth defects” was by O’Leary and colleagues.26 Like other similarly limited studies, this one involved only children younger than 6 years and didn’t assess any of the important neurobehavioral outcomes of FAS.

FAS encompasses much more than visible birth defects. As the aforementioned ACOG tool kit stated, “For every child born with FAS, many more children are born with neurobehavioral deficits caused by alcohol exposure but without the physical characteristics of FAS.”

The costs of FAS are felt with dollars, too

The financial cost to our nation is extraordinary. In 1991, Abel and Sokol estimated the incremental annual cost of treating FAS at nearly $75 million, with about three-quarters of that cost associated with FAS cases involving mental retardation.27

A 2002 assessment estimated the lifetime cost for each individual with FAS (adjusting for the change in the cost of medical care services, lost productivity, and inflation) at $2 million. This figure consists of $1.6 million for medical treatment, special education, and residential care for persons with mental retardation, and $0.4 million for productivity losses.28

Where human studies fall short, animal studies can help elucidate causation

Unquestionably, there are flaws in the existing literature on the causation of FAS. Many studies rely on self-reporting by pregnant women, and underreporting in these cases is a real concern. There often are other confounders potentially negatively affecting fetal development, making it difficult to differentiate causation. The animal studies that don’t share these limitations do suggest a causal relationship between antenatal alcohol exposure and poor obstetric outcomes, however.29 These studies suggest mechanisms such as altered gene expression, oxidative stress, and apoptosis (programmed cell death).30

Warren, Hewitt, and Thomas describe how intrauterine alcohol exposure interferes with the function of L1CAM, the L1 cell-adhesion molecule.31 They noted that just one drink could interfere with the ability of L1CAM to mediate cell adhesion and axonal growth. Prenatal alcohol exposure is also thought to contribute to interference in neurotransmitter and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor coupling, which may have potential therapeutic implications.32

Considerations in FAS identification and treatment

There is a potential to identify alcohol exposure in the womb. The majority of ingested alcohol is eventually converted to carbon dioxide and water in both maternal and fetal circulations, which has hampered the identification of biomarkers for clinical use in FAS. Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol, may prove to be such markers.33 FAEEs have been measured in a variety of tissues, including blood and meconium. FAEEs can be measured in both neonatal and maternal hair samples.

A study evaluating the utility of such testing in 324 at-risk pregnancies revealed 90% sensitivity and 90% specificity for identifying “excessive drinking” using a cutoff of 0.5 ng/mg.34

Research shows potential therapeutic approaches during pregnancy. While the use of biomarkers has the potential to assist with the identification of at-risk newborns, it merely identifies past alcohol use; it doesn’t necessarily permit identification and prevention of the known negative pediatric sequelae. Preliminary animal studies reveal the potential benefit of neuroprotective peptides to prevent brain damage in alcohol-exposed mice.35 Further research is ongoing.

Treatment: The earlier the better

Early diagnosis and a positive environment improve outcomes. It is well established that early intervention improves outcomes. One comprehensive review of 415 patients with FAS noted troubling outcomes in general for adolescents and adults.36 Over their life spans, the prevalence of such outcomes was:

- 61% for disrupted school experiences

- 60% for trouble with the law

- 50% for confinement (in detention, jail, prison, or a psychiatric or alcohol/drug inpatient setting)

- 49% for inappropriate sexual behaviors on repeated occasions

- 35% for alcohol/drug problems.

The odds of escaping these adverse life outcomes are increased up to fourfold when the individual receives a FAS or FASD diagnosis at an earlier age and is reared in a stable environment.36

Barrier to treatment: A mother’s guilt. One of the challenges I’ve learned from my sister-in-law is the stigma mothers face when they bring their child in for services once the diagnosis of FAS is suspected. While adoptive mothers obviously can’t be held accountable for the intrauterine environment to which a fetus is exposed, the same can’t be said of biologic mothers. Therefore, there is a real risk that a mother who is unwilling or unable to face the potentially devastating news that her baby’s issues might be related to choices she made during pregnancy, might not bring her child in for necessary assessment and treatment. Therefore, prevention is a key proponent of treatment.

Prevent FAS: Provide contraception, screen for alcohol use, intervene

While ObGyns aren’t likely to diagnose many children with FAS, we are in an excellent position to try to prevent this tragedy through our counseling of reproductive-aged women. I suspect that most obstetricians spend a considerable amount of time discussing much less frequent obstetric sequelae, such as listeriosis, in the prenatal care setting. Validated alcohol screening tools take moments to administer, and once patients who might have alcohol problems are identified, either a serious discussion about contraception or an honest discussion of FAS may be appropriate. There have been a number of screening tools developed.

The CAGE screen is frequently taught in medical schools, but it isn’t as sensitive for women or minorities.19

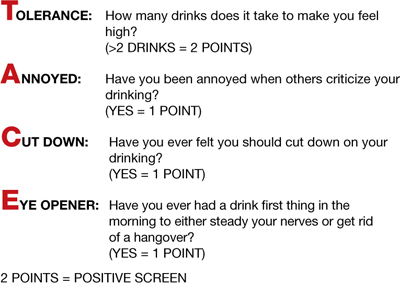

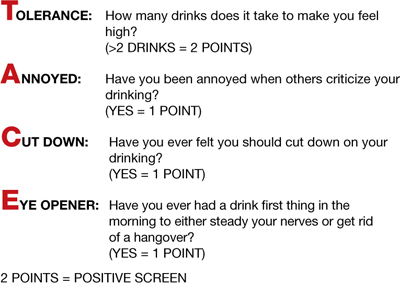

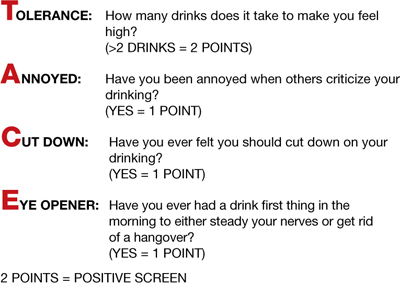

The T-ACE (Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut Down, Eye-opener) tool involves four questions that take less than 1 minute to administer (FIGURE 1).39

TWEAK is another potential tool identified by Russell and colleagues (Tolerance, Worry, Eye opener, Amnesia, and Cut down in drinking).39 Other methods utilized include an AUDIT screen and a CRAFFT screen.40 Regardless of which tool is utilized, screening is not time-consuming and is better than merely inquiring about alcohol consumption in general.

FIGURE 1 T-ACE validated alcohol screening tool

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. At risk drinking and illicit drug use: Ethical issues in obstetric and gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1449–1460.

When alcohol use is found, intervene

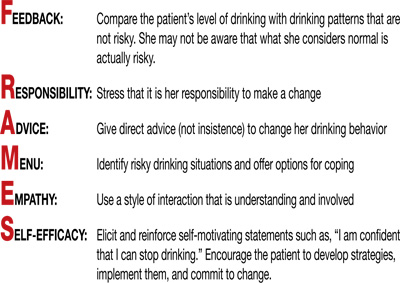

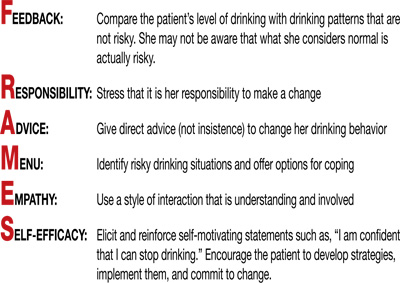

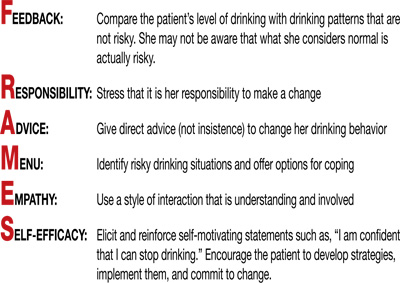

Once patients with at-risk behavior are identified, obstetric staff should offer brief interventions to influence problem drinking. Miller and Sanchez summarized the key elements that were most successful in these programs with the acronym FRAMES: Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, Self-efficacy (FIGURE 2).41 This approach has been formally evaluated in the CDC’s multisite pilot study entitled Project CHOICES.42

In this motivational intervention, sexually active, fertile women of reproductive age underwent up to four motivational counseling sessions and one visit to a provider. At 6 months, 69% of women reduced their risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy—although the women who drank the least amount had the greatest benefit, primarily by choosing effective contraception, but also by reducing alcohol intake.

FIGURE 2 FRAMES model to deliver brief interventions

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Drinking and reproductive health: A fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevention tool kit. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2006.

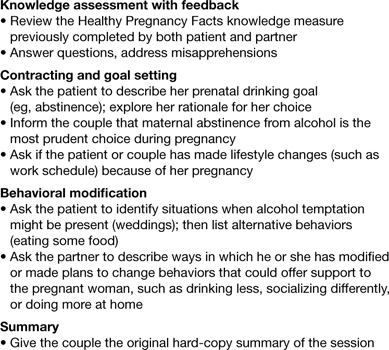

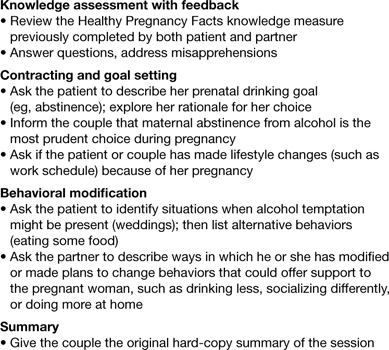

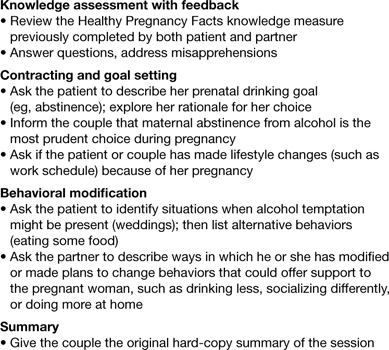

A single, brief intervention is effective in already-pregnant women. Chang and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of a single-session brief intervention given to pregnant women with positive T-ACE screens and their partners (FIGURE 3).43 Either the study nurse or physician participated in the intervention, and each single session took 25 minutes on average. The pregnant women with the highest level of alcohol use reduced their drinking the most, and this effect was even larger when their partners participated. Other studies of brief interventions showed similar benefits.44,45

Another study evaluating a brief intervention involving training of health-care providers to improve screening rates revealed improved detection and therapy among at-risk patients.46

FIGURE 3 Single session, 25-minute intervention for patients and their partners

Source: Chang G, McNamara T, Orav J, et al. Brief intervention for prenatal alcohol use: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):991–998.

FAS prevention begins with routine counseling and contraception

Although FAS is often thought of in relation to obstetric populations, appointments for preconception counseling or routine health maintenance among women of reproductive age are an essential tool in FAS prevention. As previously mentioned, since approximately half of all pregnancies in this country are unplanned, long-acting reversible contraception is widely available to facilitate improved family planning.

Other contraceptive options also should be discussed. ACOG has teamed up with the CDC to develop a phone app for providers to use at the patient’s bedside to assist with identification and treatment of women at risk for alcohol use during pregnancy.47

The stakes are high, it’s time to step up

As obstetricians, we are powerless to prevent many conditions—such as vasa previa, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, and amniotic band syndrome. FAS is 100% preventable.

There aren’t that many proven teratogens in our profession, and there are none that involve behavior that is more socially acceptable than alcohol consumption. It is time for our profession to encourage women to appreciate how small a percentage of one’s life is spent pregnant, how many more years there are to enjoy an occasional cocktail, and how very high the stakes are during this important period of their lives. Oh, how I wish someone had been able to communicate all of this to sweet Charlie’s biologic mother. I am so grateful he’s getting the exceptional care he’s getting and very optimistic regarding his future. I only hope others in his situation are given the same opportunities.

Prenatal counseling

Louise Wilkins-Haug, MD, PhD (January 2008)

Prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome requires routine screening of all women of reproductive age

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Baram M. Moms-to-be get mixed messages on drinking. ABC News. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=2654849&page=1#.UM9l-RyeARY. Published November 15 2006. Accessed December 14, 2012.

2. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Alcohol consumption and the outcomes of pregnancy (RCOG Statement No. 5). London UK: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. January 3, 2006.

3. Pearson C. Alcohol during pregnancy: How dangerous is it really? The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/04/06/alcohol-during-pregnancy_n_845103.html. Published April 6 2011. Updated September 16, 2011. Accessed December 14, 2012.

4. Kelly YJ, Sacker A, Gray R, et al. Light drinking during pregnancy: still no increased risk for socioemotional difficulties or cognitive deficits at 5 years of age? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(1):41-48.Epub Oct 5, 2010.

5. Kelly Y, Sacker A, Gray R, Kelly J, Wolke D, Quigley MA. Light drinking in pregnancy a risk for behavioural problems and cognitive deficits at 3 years of age? Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(1):129-140.Epub Oct 30, 2008.

6. Zhou F. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Study Group (FASDSG). Research Society on Alcoholism. http://rsoa.org/fas.html. Updated September 9 2010. Accessed December 14, 2012.

7. Kelly S, Day N, Streissguth AP. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on social behavior in humans and other species. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22(2):143-149.

8. Vaglenova J, Petkov V. Fetal alcohol effects in rats exposed pre-and postnatally to a low dose of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(3):697-703.

9. Schneider M, Moore C, Kraemer G. Moderate alcohol during pregnancy: learning and behavior in adolescent rhesus monkeys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(9):1383-1392.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Data and statistics in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/data.html. Updated August 16 2012. Accessed December 14, 2012.

11. Egeland G, Perham-Hestere KA, Gessner BD, Ingle D, Berner JE, Middaugh J. Fetal alcohol syndrome in Alaska 1977 through 1992: an administrative prevalence derived from multiple data sources. Am J Pub Health. 1998;88(5):781-786.

12. Jones K, Smith D, Ulleland C, Streissguth A. Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers. Lancet. 1973;1(7815):1267-1271.

13. Institute of Medicine. Fetal alcohol syndrome: diagnosis epidemiology, prevention, and treatment (1996). http://www.come-over.to/FAS/IOMsummary.htm. Accessed December 14, 2012.

14. Committee of Substance Abuse and Committee on Children with Disabilities. American Academy of Pediatrics. Fetal alcohol syndrome and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):358-361.

15. US Department of Health & Human Services. US Surgeon General releases advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/news/2005/02/sg02222005.html. Published February 21 2005. Accessed December 13, 2012.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age–United States 2006–2010. MMWR. 2012;61(28):534-538.http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6128a4.htm?s_cid=mm6128a4_w. Accessed December 17, 2012.

17. Landgren M, Svensson L, Stromland K, Gronlund M. Prenatal alcohol exposure and neurodvelopmental disorders in children adopted from Eastern Europe. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1178-1185.doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0712.

18. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Drinking and reproductive health: A fetal alcohol spectrum disorders prevention tool kit. http://www.acog.org/~/media/Departments/Tobacco%20Alcohol%20and%20Substance%20Abuse/FASDToolKit.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20121217T1504384811. Published 2006. Accessed December 14 2012.