User login

- Consider injections of hyaluronic acid only after conservative therapy has been tried for at least 3 months or the patient is unable to tolerate NSAIDs.

- Stress to patients that pain relief may not be fully experienced until 5 to 7 weeks following the last injection.

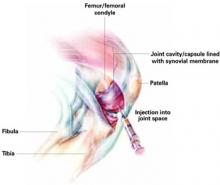

Hyaluronic acid injections can help relieve pain for carefully selected patients with knee osteoarthritis. But this option should be reserved for those whose pain has not responded to adequate trials of systemic therapeutic agents (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], cyclooxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitors), topical agents, or to lifestyle modifications such as weight reduction and exercise.

Hyaluronic acid injections may also be indicated when knee surgery must be delayed for middle-aged persons.1

In spite of the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this therapy, uncertainty about its efficacy exists among the medical community. A recent meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis that included 22 published and unpublished, English and non-English, single or double-blinded, randomized controlled trials in humans showed that hyaluronic acid has only a small effect on pain relief when compared with placebo.2

We provide here a stringent test of the efficacy of viscosupplementation for relieving knee pain from osteoarthritis with a meta-analysis that includes only data from randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials of hyaluronic acid that measured pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS), the most widely accepted method for pain evaluation.

Long time coming

Balazs first proposed hyaluronic acid as a treatment for patients with arthritic diseases in 1942. In the early 1970s, therapeutic studies were begun to test the efficacy of hyaluronic acid on knee osteoarthritis. The results were encouraging and side effects were few.28 With the FDA’s approval in 1998, intra-articular “viscosupplementation” with hyaluronic acid—also called hyaluronan or hyaluronate, and the hylan derivatives of hyaluronic acid—is a welcome option for many of the 16 million older Americans with osteoarthritis of the knee.1

Methods

Selection of studies

We identified clinical trials of viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid in humans published in English from 1965 through August 2004 through a computerized literature search of Medline. The keyword used was “hyaluronic acid,” which was combined with “trial” or “osteoarthritis knee” or “viscosupplementation.” We conducted an additional manual search of the reference lists of included articles and review articles. We also searched the Cochrane Library and websites of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for information on hyaluronic acid in knee osteoarthritis. We identified 1872 articles with this search process.

Of the 1872 articles, we identified by title and abstract 33 that might be pertinent to this study, including 17 randomized trials. We excluded reviews, meta-analyses, comparison trials, and trials reporting VAS as part of the WOMAC (Western Ontario McMaster Universities Index) scale. We attempted to contact authors of the studies that used a double-blind, randomized controlled design, to obtain any data that may not have been included in the publications. Three authors provided the details requested; the others did not respond or stated that additional data were not available. Of the 17 randomized trials we identified, 8 were excluded because they were open, single-blinded, or did not use the VAS to measure pain outcomes.3-10 The remaining 9 double-blinded, placebo controlled, randomized clinical trials of viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis that did use a VAS to measure pain were included in this meta-analysis (TABLE 1). Because one of the studies (by Henderson) included 2 subgroups of pain severity, these were considered as 2 separate trials. The trial by Petrella had 2 treatment groups, one with only hyaluronic acid and the other with hyaluronic acid and NSAIDs. We considered them separately in the analysis, resulting in a total of 11 clinical trials for the meta-analysis.19 Henceforth in this report, we will refer to 11 rather than 9 clinical trials.

Extraction of data

Two investigators independently extracted the following data for each study: year of publication, study design, mean age, number of patients enrolled in each treatment group, number of doses of treatment used, and outcomes measured. When disagreements between investigators occurred, the point of disagreement was discussed until a consensus was reached. Since the treatment duration and the time post-treatment when pain was assessed varied among the trials, we grouped outcomes into four time intervals: at 1 week, 5 to 7 weeks, 8 to 12 weeks, and 15 to 22 weeks after the last hyaluronic acid injection.

Statistical analysis

The outcome was knee pain reported by patients on activity or at rest, measured using a VAS of 100 mm. The results of the clinical trials were recorded as the mean differences of change from baseline between the treatment and placebo groups. If not reported in the publication or provided by the authors, standard error was imputed using the method of Follman et al.20 We used the method of Chalmers for measuring the quality of randomized trials, with 2 of the authors rating the studies independently.21

This clinical trial grading system takes into account the following aspects of the trial to determine a quality score: evaluation of recruitment of subjects, rejection log, therapeutic regimen definition, randomization, blinding, prior estimates of numbers, testing compliance, statistical inference, use of appropriate statistical analysis, handling of withdrawal and side effects, dates of starting and ending, timing and tabulation of events. Because 4 of the trials had poor quality scores, an additional analysis excluding these 4 was performed. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used to obtain the summary estimates.22,23

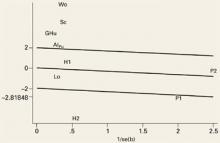

An important element of meta-analysis is exploration of the heterogeneity of the outcomes and the possible causes of heterogeneity if it exists. Heterogeneity is the degree to which results vary from study to study. If a test for heterogeneity is statistically significant, there is significant variability among the treatment effects observed in the trials. We explored heterogeneity using Galbraith plots (FIGURE 1).24 In the absence of heterogeneity, all points fall within the confidence limits. Because we did find heterogeneity among these trials, we developed random-effect regression models to explore 3 possible sources of heterogeneity in the efficacy of hyaluronic acid; pain (measured at rest or on activity), the form used (hyaluronan or hylan G-F20), and the quality of the study method (good or poor).

Publication bias was assessed by the Egger et al regression asymmetry test.25 Analyses were performed using the meta-analytic software program of STATA, Inc (College Station, Tex; available at www.stata.com).

FIGURE 1

Evidence of heterogeneity for the studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1)

This Galbraith plot shows standardized effects (b/se=mean difference/standard error) as a function of study precision (1/standard error), slope of the line shows average effect over all the studies with upper and lower lines denoting an approximate 95% confidence interval for this common effect. Under the hypothesis of study heterogeneity, the common slope intersect zero at 1/se=0, and 95% of all study estimates (authors initials) will fall within the confidence interval of the regression line. Gr: Grecomoro; Pu: Puhl; H1: Henderson 1; H2: Henderson 2; Sc: Scale; Lo: Lohmander; Al: Altman; Wo: Wobig; Hu: Huskisson; P1: Petrella 1; P2: Petrella 2.

Results

The 11 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical trials that met our inclusion criteria are summarized in TABLE 1. Nine trials used hyaluronic acid, hyaluronan, or hyaluronate (all types will be referred to as hyaluronan in the text), and 2 studies used hylan GF-20. Only 3 hyaluronan trials have published outcome data at 15 to 22 weeks follow-up. Treatment was administered to patients as 3 to 5 weekly injections, with the exception of the Grecomoro study in which treatment was administered twice weekly. The control group in 10 trials received intra-articular saline injections as placebo. In the Puhl study the investigators added 0.25 mg of hyaluronic acid to the saline injections to impart viscosity to the solution. The mean age of the subjects for the 11 trials was 63 years.

Eight trials received support from pharmaceutical companies and 3 (the 2 by Henderson and the Grecomoro study) did not disclose any pharmaceutical support. One study was conducted in the United States, 3 in the UK, 3 in Germany, 1 in Sweden, 1 in Italy, and 2 in Canada. Five of the studies had scores over a cutoff quality score of >0.75,12,13,15,16,19 indicating they were good-quality randomized controlled trials; the remaining 4 had scores below 0.75.11,14,16,17

The outcomes of the 11 trials are summarized in TABLE 2. Patients’ pain ratings in both the active treatment and placebo groups improved in all the trials. Mean difference between improvements in treatment and placebo groups are shown in FIGURES 2A-2D for pain assessed at weeks 1, 5 to 7, 8 to 12 and 15 to 22, respectively. In each figure, we show the summary estimate of effect size with all the trials included and after excluding the 4 trials considered of poor quality, shown as “good quality studies.”

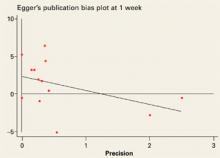

The mean difference in pain scores between treatment and placebo at week 1 was 4.4 (95% CI, +1.1, +7.2) and –1.0 (95% CI, -3.2, +1.2) for analysis restricted to the 7 good quality trials. The mean difference in pain scores at 5 to 7 weeks was 17.6 (95% CI, +7.5, +28.0) and 7.2 (95% CI, +2.4, +12.0) for the analysis restricted to the 2 good quality studies. At weeks 8 to 12 the mean difference in VAS between treatment and control was 18.1 (95% CI, +6.3, +29.9), and 7.1 (95% CI, +3.0, +11.3) in the analysis restricted to good quality trials. At weeks 15 to 22, the mean difference was 4.4 (95% CI, –15.3, +24.1). The Egger test was not statistically significant (2.3; P=.096; 95% CI, –0.5, +5.2) suggesting that there is no publication bias.

High heterogeneity was observed at all time intervals except 1 week (FIGURE 1). Of the 5 trials outside the confidence bounds (positioned 2 units above and below the regression line), 4 were poor-quality studies.

TABLE 3 shows the random-effect regression models we used to test the influence on the outcome of type of pain measured (pain with activity or pain at rest), type of medication (hyaluronan or hylan G-F 20), and study quality (good or poor). No significant association between treatment efficacy and type of pain used as outcome variable was observed. Clinical trials using hylan GF-20 showed statistically significant better results than those using hyaluronan at weeks 5 to 7 and 8 to 12. Poor-quality studies showed a larger treatment effect, but the difference was statistically significant only at week 1.

TABLE 3

Regression models to assess the sources of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis

| WEEK 1 | WEEKS 5–7 | WEEKS 8–12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | |

| Pain | ||||||

| With activity | 1.7 (3.8) | 1.8 (4.3) | –0.5 (4.6) | |||

| At rest | [–5.8, +9.2] | 0.657 | [–6.6, +10.2] | 0.671 | [–9.5, +8.6] | 0.916 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Hyaluronan** | –3.4 (6.8) | 0.614 | 17.5 (4.9) | <0.001 | 14.8 (6.1) | 0.016 |

| Hylan G-F 20 | –16.7, +9.9] | [+7.8, +27.1] | [+2.8, +26.8] | |||

| Quality* | ||||||

| Poor (<0.75) | –19.9 (5.7) | 0.001 | –7.4 (4.9) | 0.131 | –11.7 (7.0) | 0.092 |

| Good (≥0.75) | [–31.1, –8.7] | [–17.0, +2.2] | [–25.3, +1.9] | |||

| Constant | 18.4 (5.6) | 0.001 | 13.5 (4.5) | 0.003 | 19.2 (5.8) | 0.001 |

| [+7.5, +29.3] | [+4.6, +22.3] | [+7.9, +30.5] | ||||

| *<.75 quality score: Grecomoro .439, Scale .570, Wobig .731, Huskisson .718. | ||||||

| ** 9 trials for hyaluronan (3 for Hyalgan®) and 2 trials for hylan G-F20 (Synvisc®). | ||||||

Discussion

This meta-analysis synthesized data from 9 randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid. Our findings show significantly decreased pain as measured by VAS at 5 to 7 weeks and at 8 to 12 weeks after the last injection. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid was not more effective than placebo in relieving pain at 1 week or at 15 to 22 weeks after the last injection. Because only 3 of the trials assessed patients after 12 weeks, however, the sample size is too small to definitively rule out a significant therapeutic effect after 12 weeks.

Reasons for the differences in efficacy among trials of hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis include dose, type, and frequency of administration, genetic or age differences among the study subjects, severity of osteoarthritis, time of follow-up, and quality of the studies. We confirmed that the treatment effect is time dependent. Although our meta-regression analysis (TABLE 2) suggests that hylan GF-20 is more effective than hyaluronan at 5 to 12 weeks, the number of clinical trials is relatively small and both of the hylan G-F20 studies were of poor quality. Therefore, we cannot say with confidence that one form is better than the other. Data in these trials were insufficient to assess the impact of body mass index, genetics, or severity of osteoarthritis.

We did not evaluate functional improvement in this meta-analysis because functional status was not measured in some trials and the assessment methods were too variable in the trials that did assess functional status. Publication bias, or the possibility that unpublished data would contradict the results of published studies, is always a potential source of bias in meta-analysis. However, the Egger test was not statistically significant (6.5; 95% CI, –0.5, +13.5) suggesting that there is no publication bias.25

Finally, the presence of heterogeneity of results indicates there were important differences among the studies. Exclusion of clinical trials considered of poor quality diminished this heterogeneity substantially. Subanalysis restricted to good-quality studies supports the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis pain, although the effect size is smaller when one considers only the good quality studies.

There are 2 other potential limitations of this meta-analysis. Five studies allowed pain to be treated with analgesics such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs,12,13,16-18 and use of acetaminophen or NSAIDs may have altered the response to hyaluronic acid treatment. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed in only 2 studies (by Altman and Huskisson),16,18 wherein a post-hoc and “last observation carried forward” analysis showed a trend favoring hyaluronic acid. The treatment effects may have been smaller had the other trials used an intention to treat analysis.

This meta-analysis confirms that viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid is modestly effective in short term relief of pain in knee osteoarthritis. Our meta-analysis included only double-blinded, randomized trials published in English language in humans using VAS as the pain outcome measure, and our conclusions are very similar to those of Lo.2

Indications for use. Hyaluronic acid is helpful in relieving pain for carefully selected patients with knee osteoarthritis who have not responded to adequate use of systemic therapeutic agents, including acetaminophen, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors and topical agents, along with lifestyle modification such as weight reduction and exercise.

Patients should have a trial for at least three months of conservative therapy or be unable to tolerate NSAIDs before a decision to give 3- to 5-injection course with hyaluronic acid is made.

Hyaluronic acid may be an option when there is a need to delay knee surgery in middle-aged persons1 or for patients who have failed other treatments.

Time to pain relief. To improve adherence to treatment, tell patients receiving intra-articular hyaluronic acid that the benefits in pain reduction may not be noticeable until 5 to 10 weeks after the last injection.

Cost. Although the cost of hyaluronic acid treatment is covered by Medicare and most insurance plans for symptomatic osteoarthritis of knee, documentation in patient medical records should indicate the signs and symptoms supporting the diagnosis and functional impairment. Objective data to support a diagnosis of osteoarthritis such as x-ray, arthroscopy report, computed tomography scan, or magnetic resonance imaging should be available in the event of a review.

The cost of 1 hyaluronic acid (30 mg/mL) injection is approximately $230. Considering a course of 3 to 5 weekly knee injections, and adding other pharmacy, hospital, or clinic charges, the cost per treatment may exceed $1000 per knee.26,27 The cost-benefit of pain control with viscosupplementation must be carefully compared with other therapeutic agents and regimens currently available for knee osteoarthritis management.

FIGURE 3

Studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1)

Egger’s publication bias plot for the studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1) not significant (+2.3, P=0.096, 95% CI: –0.5, +5.2).

Acknowledgments

Jeff Welge, PhD, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Center for Bio-statistical Services, for comments on final data analysis and presentation, Marie Marley, PhD for editing the manuscript, and Charity Noble for help in preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Arvind Modawal, MD, MPH, MRCGP, University of Cincinnati Department of Family Medicine/Geriatrics, PO Box 670582, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0582. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Cefalu CA, Waddell DS. Viscosupplementation: Treatment alternative for osteoarthritis of the knee. Geriatrics 1999;54:51-57.

2. Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T, Felson DT. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis. JAMA 2003;290:3115-3121.

3. Jones AC, Pattrick M, Doherty S, Doherty M. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid compared to intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide in inflammatory knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1995;3:269-273.

4. Graf J, Neusel E, Schneider E, Niethard FU. Intra-articular treatment with hyaluronic acid in osteoarthritis of the knee joint: a controlled clinical trial versus mucopolysaccharide polysulfuric acid ester. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1993;11:367-72.

5. Dougados M, Nguyen M, Listrat V, Amor B. High molecular weight sodium hyaluronate (hyalectin) in osteoarthritis of the knee: A one year placebo-controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1993;1:97-103.

6. Adams ME. An analysis of clinical studies of the use of cross-linked hyaluronan, hylan, in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Supp 1993;39:16-18.

7. Grecomoro G, Piccione F, Letizia G. Therapeutic synergism between hyaluronic acid and dexamethasone in the intra-articular treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a preliminary open study. Curr Med Res Opin 1992;13:49-55.

8. Leardini G, Mattara L, Franceschini M, Perbellini A. Intra-articular treatment of knee osteoarthritis. A comparative study between hyaluronic acid and 6-methyl prednisolone acetate. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1991;9:375-381.

9. Wu J, Shih L, Hsu H, Chen T. The double-blind test of sodium hyaluronate (ARTZ) on osteoarthritis knee. Chin Med J (Taipei) 1997;59:99-106.

10. Dixon AS, Jacoby RK, Berry H, Hamilton EB. Clinical trial of intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Curr Med Res Opin 1988;11:205-213.

11. Grecomoro G, Martorana U, Di Marco C. Intra-articular treatment with sodium hyaluronate in gonarthrosis: a controlled clinical trial versus placebo. Pharmather 1987;5:137-141.

12. Puhl W, Bernau A, Greiling H, Kopcke W, Pforringer W, Steck KJ. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate in osteoarthritis of the knee: a multicenter, double-blind study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1993;1:233-241.

13. Henderson EB, Smith EC, Pegley F, Blake DR. Intra-articular injections of 750 kD hyaluronan in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a randomized single centre double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 91 patients demonstrating lack of efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis 1994;53:529-554.

14. Scale D, Wobig M, Wolpert W. Viscosupplementation of osteoarthritic knees with Hylan: A treatment schedule study. Curr Ther Res 1994;55:220-232.

15. Lohmander LS, Dalen N, Englund G, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronan injections in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled multicentre trial. Hyaluronan Multicentre Trial Group [see comments]. Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:424-431.

16. Altman RD, Moskowitz R. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan®) in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol 1998;25:2203-2212.

17. Wobig M, Dickhut A, Maier R, Vetter G. Viscosupplementation with Hylan G-F-20: A 26-week controlled trial of efficacy and safety in the osteoarthritic knee. Clin Ther 1998;20:410-423.

18. Huskisson EC, Donnelly S. Hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology 1999;38:602-607.

19. Petrella RJ, DiSilvestro MD, Hildebrand C. Effects of hyaluronate sodium on pain and physical functioning in osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:292-298.

20. Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:769-773.

21. Chalmers TC, Smith H, Jr, Blackburn B, et al. A Method for Assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials 1981;2:31-49.

22. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-188.

23. Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D, Ancona-Berk VA, Chalmers TC. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 1987;316:450-455.

24. Galbraith R. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med 1988;7:889-894.

25. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-634.

26. CIGNA Government Services. Not otherwise classified drug fee schedule. Available at: www.cignamedicare.com/partb/fsch/2004/q2/noc.html. Accessed on June 20, 2005.

27. Empire Medicare Services. Local coverage determination. Hyaluronate polymers (Synvisc, Hyalgan) (A02-0011-R3). Available at: www.empiremedicare.com/Nyorkpolicya/policy/A02-0011-R_FINAL.htm.

28. Peyron JG, Balazs EA. Preliminary clinical assessment of Na-hyaluronate injection into human arthritic joints. Pathol Biol 1974;22:731-736.

- Consider injections of hyaluronic acid only after conservative therapy has been tried for at least 3 months or the patient is unable to tolerate NSAIDs.

- Stress to patients that pain relief may not be fully experienced until 5 to 7 weeks following the last injection.

Hyaluronic acid injections can help relieve pain for carefully selected patients with knee osteoarthritis. But this option should be reserved for those whose pain has not responded to adequate trials of systemic therapeutic agents (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], cyclooxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitors), topical agents, or to lifestyle modifications such as weight reduction and exercise.

Hyaluronic acid injections may also be indicated when knee surgery must be delayed for middle-aged persons.1

In spite of the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this therapy, uncertainty about its efficacy exists among the medical community. A recent meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis that included 22 published and unpublished, English and non-English, single or double-blinded, randomized controlled trials in humans showed that hyaluronic acid has only a small effect on pain relief when compared with placebo.2

We provide here a stringent test of the efficacy of viscosupplementation for relieving knee pain from osteoarthritis with a meta-analysis that includes only data from randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials of hyaluronic acid that measured pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS), the most widely accepted method for pain evaluation.

Long time coming

Balazs first proposed hyaluronic acid as a treatment for patients with arthritic diseases in 1942. In the early 1970s, therapeutic studies were begun to test the efficacy of hyaluronic acid on knee osteoarthritis. The results were encouraging and side effects were few.28 With the FDA’s approval in 1998, intra-articular “viscosupplementation” with hyaluronic acid—also called hyaluronan or hyaluronate, and the hylan derivatives of hyaluronic acid—is a welcome option for many of the 16 million older Americans with osteoarthritis of the knee.1

Methods

Selection of studies

We identified clinical trials of viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid in humans published in English from 1965 through August 2004 through a computerized literature search of Medline. The keyword used was “hyaluronic acid,” which was combined with “trial” or “osteoarthritis knee” or “viscosupplementation.” We conducted an additional manual search of the reference lists of included articles and review articles. We also searched the Cochrane Library and websites of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for information on hyaluronic acid in knee osteoarthritis. We identified 1872 articles with this search process.

Of the 1872 articles, we identified by title and abstract 33 that might be pertinent to this study, including 17 randomized trials. We excluded reviews, meta-analyses, comparison trials, and trials reporting VAS as part of the WOMAC (Western Ontario McMaster Universities Index) scale. We attempted to contact authors of the studies that used a double-blind, randomized controlled design, to obtain any data that may not have been included in the publications. Three authors provided the details requested; the others did not respond or stated that additional data were not available. Of the 17 randomized trials we identified, 8 were excluded because they were open, single-blinded, or did not use the VAS to measure pain outcomes.3-10 The remaining 9 double-blinded, placebo controlled, randomized clinical trials of viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis that did use a VAS to measure pain were included in this meta-analysis (TABLE 1). Because one of the studies (by Henderson) included 2 subgroups of pain severity, these were considered as 2 separate trials. The trial by Petrella had 2 treatment groups, one with only hyaluronic acid and the other with hyaluronic acid and NSAIDs. We considered them separately in the analysis, resulting in a total of 11 clinical trials for the meta-analysis.19 Henceforth in this report, we will refer to 11 rather than 9 clinical trials.

Extraction of data

Two investigators independently extracted the following data for each study: year of publication, study design, mean age, number of patients enrolled in each treatment group, number of doses of treatment used, and outcomes measured. When disagreements between investigators occurred, the point of disagreement was discussed until a consensus was reached. Since the treatment duration and the time post-treatment when pain was assessed varied among the trials, we grouped outcomes into four time intervals: at 1 week, 5 to 7 weeks, 8 to 12 weeks, and 15 to 22 weeks after the last hyaluronic acid injection.

Statistical analysis

The outcome was knee pain reported by patients on activity or at rest, measured using a VAS of 100 mm. The results of the clinical trials were recorded as the mean differences of change from baseline between the treatment and placebo groups. If not reported in the publication or provided by the authors, standard error was imputed using the method of Follman et al.20 We used the method of Chalmers for measuring the quality of randomized trials, with 2 of the authors rating the studies independently.21

This clinical trial grading system takes into account the following aspects of the trial to determine a quality score: evaluation of recruitment of subjects, rejection log, therapeutic regimen definition, randomization, blinding, prior estimates of numbers, testing compliance, statistical inference, use of appropriate statistical analysis, handling of withdrawal and side effects, dates of starting and ending, timing and tabulation of events. Because 4 of the trials had poor quality scores, an additional analysis excluding these 4 was performed. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used to obtain the summary estimates.22,23

An important element of meta-analysis is exploration of the heterogeneity of the outcomes and the possible causes of heterogeneity if it exists. Heterogeneity is the degree to which results vary from study to study. If a test for heterogeneity is statistically significant, there is significant variability among the treatment effects observed in the trials. We explored heterogeneity using Galbraith plots (FIGURE 1).24 In the absence of heterogeneity, all points fall within the confidence limits. Because we did find heterogeneity among these trials, we developed random-effect regression models to explore 3 possible sources of heterogeneity in the efficacy of hyaluronic acid; pain (measured at rest or on activity), the form used (hyaluronan or hylan G-F20), and the quality of the study method (good or poor).

Publication bias was assessed by the Egger et al regression asymmetry test.25 Analyses were performed using the meta-analytic software program of STATA, Inc (College Station, Tex; available at www.stata.com).

FIGURE 1

Evidence of heterogeneity for the studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1)

This Galbraith plot shows standardized effects (b/se=mean difference/standard error) as a function of study precision (1/standard error), slope of the line shows average effect over all the studies with upper and lower lines denoting an approximate 95% confidence interval for this common effect. Under the hypothesis of study heterogeneity, the common slope intersect zero at 1/se=0, and 95% of all study estimates (authors initials) will fall within the confidence interval of the regression line. Gr: Grecomoro; Pu: Puhl; H1: Henderson 1; H2: Henderson 2; Sc: Scale; Lo: Lohmander; Al: Altman; Wo: Wobig; Hu: Huskisson; P1: Petrella 1; P2: Petrella 2.

Results

The 11 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical trials that met our inclusion criteria are summarized in TABLE 1. Nine trials used hyaluronic acid, hyaluronan, or hyaluronate (all types will be referred to as hyaluronan in the text), and 2 studies used hylan GF-20. Only 3 hyaluronan trials have published outcome data at 15 to 22 weeks follow-up. Treatment was administered to patients as 3 to 5 weekly injections, with the exception of the Grecomoro study in which treatment was administered twice weekly. The control group in 10 trials received intra-articular saline injections as placebo. In the Puhl study the investigators added 0.25 mg of hyaluronic acid to the saline injections to impart viscosity to the solution. The mean age of the subjects for the 11 trials was 63 years.

Eight trials received support from pharmaceutical companies and 3 (the 2 by Henderson and the Grecomoro study) did not disclose any pharmaceutical support. One study was conducted in the United States, 3 in the UK, 3 in Germany, 1 in Sweden, 1 in Italy, and 2 in Canada. Five of the studies had scores over a cutoff quality score of >0.75,12,13,15,16,19 indicating they were good-quality randomized controlled trials; the remaining 4 had scores below 0.75.11,14,16,17

The outcomes of the 11 trials are summarized in TABLE 2. Patients’ pain ratings in both the active treatment and placebo groups improved in all the trials. Mean difference between improvements in treatment and placebo groups are shown in FIGURES 2A-2D for pain assessed at weeks 1, 5 to 7, 8 to 12 and 15 to 22, respectively. In each figure, we show the summary estimate of effect size with all the trials included and after excluding the 4 trials considered of poor quality, shown as “good quality studies.”

The mean difference in pain scores between treatment and placebo at week 1 was 4.4 (95% CI, +1.1, +7.2) and –1.0 (95% CI, -3.2, +1.2) for analysis restricted to the 7 good quality trials. The mean difference in pain scores at 5 to 7 weeks was 17.6 (95% CI, +7.5, +28.0) and 7.2 (95% CI, +2.4, +12.0) for the analysis restricted to the 2 good quality studies. At weeks 8 to 12 the mean difference in VAS between treatment and control was 18.1 (95% CI, +6.3, +29.9), and 7.1 (95% CI, +3.0, +11.3) in the analysis restricted to good quality trials. At weeks 15 to 22, the mean difference was 4.4 (95% CI, –15.3, +24.1). The Egger test was not statistically significant (2.3; P=.096; 95% CI, –0.5, +5.2) suggesting that there is no publication bias.

High heterogeneity was observed at all time intervals except 1 week (FIGURE 1). Of the 5 trials outside the confidence bounds (positioned 2 units above and below the regression line), 4 were poor-quality studies.

TABLE 3 shows the random-effect regression models we used to test the influence on the outcome of type of pain measured (pain with activity or pain at rest), type of medication (hyaluronan or hylan G-F 20), and study quality (good or poor). No significant association between treatment efficacy and type of pain used as outcome variable was observed. Clinical trials using hylan GF-20 showed statistically significant better results than those using hyaluronan at weeks 5 to 7 and 8 to 12. Poor-quality studies showed a larger treatment effect, but the difference was statistically significant only at week 1.

TABLE 3

Regression models to assess the sources of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis

| WEEK 1 | WEEKS 5–7 | WEEKS 8–12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | |

| Pain | ||||||

| With activity | 1.7 (3.8) | 1.8 (4.3) | –0.5 (4.6) | |||

| At rest | [–5.8, +9.2] | 0.657 | [–6.6, +10.2] | 0.671 | [–9.5, +8.6] | 0.916 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Hyaluronan** | –3.4 (6.8) | 0.614 | 17.5 (4.9) | <0.001 | 14.8 (6.1) | 0.016 |

| Hylan G-F 20 | –16.7, +9.9] | [+7.8, +27.1] | [+2.8, +26.8] | |||

| Quality* | ||||||

| Poor (<0.75) | –19.9 (5.7) | 0.001 | –7.4 (4.9) | 0.131 | –11.7 (7.0) | 0.092 |

| Good (≥0.75) | [–31.1, –8.7] | [–17.0, +2.2] | [–25.3, +1.9] | |||

| Constant | 18.4 (5.6) | 0.001 | 13.5 (4.5) | 0.003 | 19.2 (5.8) | 0.001 |

| [+7.5, +29.3] | [+4.6, +22.3] | [+7.9, +30.5] | ||||

| *<.75 quality score: Grecomoro .439, Scale .570, Wobig .731, Huskisson .718. | ||||||

| ** 9 trials for hyaluronan (3 for Hyalgan®) and 2 trials for hylan G-F20 (Synvisc®). | ||||||

Discussion

This meta-analysis synthesized data from 9 randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid. Our findings show significantly decreased pain as measured by VAS at 5 to 7 weeks and at 8 to 12 weeks after the last injection. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid was not more effective than placebo in relieving pain at 1 week or at 15 to 22 weeks after the last injection. Because only 3 of the trials assessed patients after 12 weeks, however, the sample size is too small to definitively rule out a significant therapeutic effect after 12 weeks.

Reasons for the differences in efficacy among trials of hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis include dose, type, and frequency of administration, genetic or age differences among the study subjects, severity of osteoarthritis, time of follow-up, and quality of the studies. We confirmed that the treatment effect is time dependent. Although our meta-regression analysis (TABLE 2) suggests that hylan GF-20 is more effective than hyaluronan at 5 to 12 weeks, the number of clinical trials is relatively small and both of the hylan G-F20 studies were of poor quality. Therefore, we cannot say with confidence that one form is better than the other. Data in these trials were insufficient to assess the impact of body mass index, genetics, or severity of osteoarthritis.

We did not evaluate functional improvement in this meta-analysis because functional status was not measured in some trials and the assessment methods were too variable in the trials that did assess functional status. Publication bias, or the possibility that unpublished data would contradict the results of published studies, is always a potential source of bias in meta-analysis. However, the Egger test was not statistically significant (6.5; 95% CI, –0.5, +13.5) suggesting that there is no publication bias.25

Finally, the presence of heterogeneity of results indicates there were important differences among the studies. Exclusion of clinical trials considered of poor quality diminished this heterogeneity substantially. Subanalysis restricted to good-quality studies supports the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis pain, although the effect size is smaller when one considers only the good quality studies.

There are 2 other potential limitations of this meta-analysis. Five studies allowed pain to be treated with analgesics such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs,12,13,16-18 and use of acetaminophen or NSAIDs may have altered the response to hyaluronic acid treatment. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed in only 2 studies (by Altman and Huskisson),16,18 wherein a post-hoc and “last observation carried forward” analysis showed a trend favoring hyaluronic acid. The treatment effects may have been smaller had the other trials used an intention to treat analysis.

This meta-analysis confirms that viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid is modestly effective in short term relief of pain in knee osteoarthritis. Our meta-analysis included only double-blinded, randomized trials published in English language in humans using VAS as the pain outcome measure, and our conclusions are very similar to those of Lo.2

Indications for use. Hyaluronic acid is helpful in relieving pain for carefully selected patients with knee osteoarthritis who have not responded to adequate use of systemic therapeutic agents, including acetaminophen, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors and topical agents, along with lifestyle modification such as weight reduction and exercise.

Patients should have a trial for at least three months of conservative therapy or be unable to tolerate NSAIDs before a decision to give 3- to 5-injection course with hyaluronic acid is made.

Hyaluronic acid may be an option when there is a need to delay knee surgery in middle-aged persons1 or for patients who have failed other treatments.

Time to pain relief. To improve adherence to treatment, tell patients receiving intra-articular hyaluronic acid that the benefits in pain reduction may not be noticeable until 5 to 10 weeks after the last injection.

Cost. Although the cost of hyaluronic acid treatment is covered by Medicare and most insurance plans for symptomatic osteoarthritis of knee, documentation in patient medical records should indicate the signs and symptoms supporting the diagnosis and functional impairment. Objective data to support a diagnosis of osteoarthritis such as x-ray, arthroscopy report, computed tomography scan, or magnetic resonance imaging should be available in the event of a review.

The cost of 1 hyaluronic acid (30 mg/mL) injection is approximately $230. Considering a course of 3 to 5 weekly knee injections, and adding other pharmacy, hospital, or clinic charges, the cost per treatment may exceed $1000 per knee.26,27 The cost-benefit of pain control with viscosupplementation must be carefully compared with other therapeutic agents and regimens currently available for knee osteoarthritis management.

FIGURE 3

Studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1)

Egger’s publication bias plot for the studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1) not significant (+2.3, P=0.096, 95% CI: –0.5, +5.2).

Acknowledgments

Jeff Welge, PhD, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Center for Bio-statistical Services, for comments on final data analysis and presentation, Marie Marley, PhD for editing the manuscript, and Charity Noble for help in preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Arvind Modawal, MD, MPH, MRCGP, University of Cincinnati Department of Family Medicine/Geriatrics, PO Box 670582, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0582. E-mail: [email protected]

- Consider injections of hyaluronic acid only after conservative therapy has been tried for at least 3 months or the patient is unable to tolerate NSAIDs.

- Stress to patients that pain relief may not be fully experienced until 5 to 7 weeks following the last injection.

Hyaluronic acid injections can help relieve pain for carefully selected patients with knee osteoarthritis. But this option should be reserved for those whose pain has not responded to adequate trials of systemic therapeutic agents (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], cyclooxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitors), topical agents, or to lifestyle modifications such as weight reduction and exercise.

Hyaluronic acid injections may also be indicated when knee surgery must be delayed for middle-aged persons.1

In spite of the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of this therapy, uncertainty about its efficacy exists among the medical community. A recent meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis that included 22 published and unpublished, English and non-English, single or double-blinded, randomized controlled trials in humans showed that hyaluronic acid has only a small effect on pain relief when compared with placebo.2

We provide here a stringent test of the efficacy of viscosupplementation for relieving knee pain from osteoarthritis with a meta-analysis that includes only data from randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials of hyaluronic acid that measured pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS), the most widely accepted method for pain evaluation.

Long time coming

Balazs first proposed hyaluronic acid as a treatment for patients with arthritic diseases in 1942. In the early 1970s, therapeutic studies were begun to test the efficacy of hyaluronic acid on knee osteoarthritis. The results were encouraging and side effects were few.28 With the FDA’s approval in 1998, intra-articular “viscosupplementation” with hyaluronic acid—also called hyaluronan or hyaluronate, and the hylan derivatives of hyaluronic acid—is a welcome option for many of the 16 million older Americans with osteoarthritis of the knee.1

Methods

Selection of studies

We identified clinical trials of viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid in humans published in English from 1965 through August 2004 through a computerized literature search of Medline. The keyword used was “hyaluronic acid,” which was combined with “trial” or “osteoarthritis knee” or “viscosupplementation.” We conducted an additional manual search of the reference lists of included articles and review articles. We also searched the Cochrane Library and websites of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for information on hyaluronic acid in knee osteoarthritis. We identified 1872 articles with this search process.

Of the 1872 articles, we identified by title and abstract 33 that might be pertinent to this study, including 17 randomized trials. We excluded reviews, meta-analyses, comparison trials, and trials reporting VAS as part of the WOMAC (Western Ontario McMaster Universities Index) scale. We attempted to contact authors of the studies that used a double-blind, randomized controlled design, to obtain any data that may not have been included in the publications. Three authors provided the details requested; the others did not respond or stated that additional data were not available. Of the 17 randomized trials we identified, 8 were excluded because they were open, single-blinded, or did not use the VAS to measure pain outcomes.3-10 The remaining 9 double-blinded, placebo controlled, randomized clinical trials of viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis that did use a VAS to measure pain were included in this meta-analysis (TABLE 1). Because one of the studies (by Henderson) included 2 subgroups of pain severity, these were considered as 2 separate trials. The trial by Petrella had 2 treatment groups, one with only hyaluronic acid and the other with hyaluronic acid and NSAIDs. We considered them separately in the analysis, resulting in a total of 11 clinical trials for the meta-analysis.19 Henceforth in this report, we will refer to 11 rather than 9 clinical trials.

Extraction of data

Two investigators independently extracted the following data for each study: year of publication, study design, mean age, number of patients enrolled in each treatment group, number of doses of treatment used, and outcomes measured. When disagreements between investigators occurred, the point of disagreement was discussed until a consensus was reached. Since the treatment duration and the time post-treatment when pain was assessed varied among the trials, we grouped outcomes into four time intervals: at 1 week, 5 to 7 weeks, 8 to 12 weeks, and 15 to 22 weeks after the last hyaluronic acid injection.

Statistical analysis

The outcome was knee pain reported by patients on activity or at rest, measured using a VAS of 100 mm. The results of the clinical trials were recorded as the mean differences of change from baseline between the treatment and placebo groups. If not reported in the publication or provided by the authors, standard error was imputed using the method of Follman et al.20 We used the method of Chalmers for measuring the quality of randomized trials, with 2 of the authors rating the studies independently.21

This clinical trial grading system takes into account the following aspects of the trial to determine a quality score: evaluation of recruitment of subjects, rejection log, therapeutic regimen definition, randomization, blinding, prior estimates of numbers, testing compliance, statistical inference, use of appropriate statistical analysis, handling of withdrawal and side effects, dates of starting and ending, timing and tabulation of events. Because 4 of the trials had poor quality scores, an additional analysis excluding these 4 was performed. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used to obtain the summary estimates.22,23

An important element of meta-analysis is exploration of the heterogeneity of the outcomes and the possible causes of heterogeneity if it exists. Heterogeneity is the degree to which results vary from study to study. If a test for heterogeneity is statistically significant, there is significant variability among the treatment effects observed in the trials. We explored heterogeneity using Galbraith plots (FIGURE 1).24 In the absence of heterogeneity, all points fall within the confidence limits. Because we did find heterogeneity among these trials, we developed random-effect regression models to explore 3 possible sources of heterogeneity in the efficacy of hyaluronic acid; pain (measured at rest or on activity), the form used (hyaluronan or hylan G-F20), and the quality of the study method (good or poor).

Publication bias was assessed by the Egger et al regression asymmetry test.25 Analyses were performed using the meta-analytic software program of STATA, Inc (College Station, Tex; available at www.stata.com).

FIGURE 1

Evidence of heterogeneity for the studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1)

This Galbraith plot shows standardized effects (b/se=mean difference/standard error) as a function of study precision (1/standard error), slope of the line shows average effect over all the studies with upper and lower lines denoting an approximate 95% confidence interval for this common effect. Under the hypothesis of study heterogeneity, the common slope intersect zero at 1/se=0, and 95% of all study estimates (authors initials) will fall within the confidence interval of the regression line. Gr: Grecomoro; Pu: Puhl; H1: Henderson 1; H2: Henderson 2; Sc: Scale; Lo: Lohmander; Al: Altman; Wo: Wobig; Hu: Huskisson; P1: Petrella 1; P2: Petrella 2.

Results

The 11 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical trials that met our inclusion criteria are summarized in TABLE 1. Nine trials used hyaluronic acid, hyaluronan, or hyaluronate (all types will be referred to as hyaluronan in the text), and 2 studies used hylan GF-20. Only 3 hyaluronan trials have published outcome data at 15 to 22 weeks follow-up. Treatment was administered to patients as 3 to 5 weekly injections, with the exception of the Grecomoro study in which treatment was administered twice weekly. The control group in 10 trials received intra-articular saline injections as placebo. In the Puhl study the investigators added 0.25 mg of hyaluronic acid to the saline injections to impart viscosity to the solution. The mean age of the subjects for the 11 trials was 63 years.

Eight trials received support from pharmaceutical companies and 3 (the 2 by Henderson and the Grecomoro study) did not disclose any pharmaceutical support. One study was conducted in the United States, 3 in the UK, 3 in Germany, 1 in Sweden, 1 in Italy, and 2 in Canada. Five of the studies had scores over a cutoff quality score of >0.75,12,13,15,16,19 indicating they were good-quality randomized controlled trials; the remaining 4 had scores below 0.75.11,14,16,17

The outcomes of the 11 trials are summarized in TABLE 2. Patients’ pain ratings in both the active treatment and placebo groups improved in all the trials. Mean difference between improvements in treatment and placebo groups are shown in FIGURES 2A-2D for pain assessed at weeks 1, 5 to 7, 8 to 12 and 15 to 22, respectively. In each figure, we show the summary estimate of effect size with all the trials included and after excluding the 4 trials considered of poor quality, shown as “good quality studies.”

The mean difference in pain scores between treatment and placebo at week 1 was 4.4 (95% CI, +1.1, +7.2) and –1.0 (95% CI, -3.2, +1.2) for analysis restricted to the 7 good quality trials. The mean difference in pain scores at 5 to 7 weeks was 17.6 (95% CI, +7.5, +28.0) and 7.2 (95% CI, +2.4, +12.0) for the analysis restricted to the 2 good quality studies. At weeks 8 to 12 the mean difference in VAS between treatment and control was 18.1 (95% CI, +6.3, +29.9), and 7.1 (95% CI, +3.0, +11.3) in the analysis restricted to good quality trials. At weeks 15 to 22, the mean difference was 4.4 (95% CI, –15.3, +24.1). The Egger test was not statistically significant (2.3; P=.096; 95% CI, –0.5, +5.2) suggesting that there is no publication bias.

High heterogeneity was observed at all time intervals except 1 week (FIGURE 1). Of the 5 trials outside the confidence bounds (positioned 2 units above and below the regression line), 4 were poor-quality studies.

TABLE 3 shows the random-effect regression models we used to test the influence on the outcome of type of pain measured (pain with activity or pain at rest), type of medication (hyaluronan or hylan G-F 20), and study quality (good or poor). No significant association between treatment efficacy and type of pain used as outcome variable was observed. Clinical trials using hylan GF-20 showed statistically significant better results than those using hyaluronan at weeks 5 to 7 and 8 to 12. Poor-quality studies showed a larger treatment effect, but the difference was statistically significant only at week 1.

TABLE 3

Regression models to assess the sources of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis

| WEEK 1 | WEEKS 5–7 | WEEKS 8–12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | Coef. (SE) [95% CI] | P value | |

| Pain | ||||||

| With activity | 1.7 (3.8) | 1.8 (4.3) | –0.5 (4.6) | |||

| At rest | [–5.8, +9.2] | 0.657 | [–6.6, +10.2] | 0.671 | [–9.5, +8.6] | 0.916 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Hyaluronan** | –3.4 (6.8) | 0.614 | 17.5 (4.9) | <0.001 | 14.8 (6.1) | 0.016 |

| Hylan G-F 20 | –16.7, +9.9] | [+7.8, +27.1] | [+2.8, +26.8] | |||

| Quality* | ||||||

| Poor (<0.75) | –19.9 (5.7) | 0.001 | –7.4 (4.9) | 0.131 | –11.7 (7.0) | 0.092 |

| Good (≥0.75) | [–31.1, –8.7] | [–17.0, +2.2] | [–25.3, +1.9] | |||

| Constant | 18.4 (5.6) | 0.001 | 13.5 (4.5) | 0.003 | 19.2 (5.8) | 0.001 |

| [+7.5, +29.3] | [+4.6, +22.3] | [+7.9, +30.5] | ||||

| *<.75 quality score: Grecomoro .439, Scale .570, Wobig .731, Huskisson .718. | ||||||

| ** 9 trials for hyaluronan (3 for Hyalgan®) and 2 trials for hylan G-F20 (Synvisc®). | ||||||

Discussion

This meta-analysis synthesized data from 9 randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid. Our findings show significantly decreased pain as measured by VAS at 5 to 7 weeks and at 8 to 12 weeks after the last injection. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid was not more effective than placebo in relieving pain at 1 week or at 15 to 22 weeks after the last injection. Because only 3 of the trials assessed patients after 12 weeks, however, the sample size is too small to definitively rule out a significant therapeutic effect after 12 weeks.

Reasons for the differences in efficacy among trials of hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis include dose, type, and frequency of administration, genetic or age differences among the study subjects, severity of osteoarthritis, time of follow-up, and quality of the studies. We confirmed that the treatment effect is time dependent. Although our meta-regression analysis (TABLE 2) suggests that hylan GF-20 is more effective than hyaluronan at 5 to 12 weeks, the number of clinical trials is relatively small and both of the hylan G-F20 studies were of poor quality. Therefore, we cannot say with confidence that one form is better than the other. Data in these trials were insufficient to assess the impact of body mass index, genetics, or severity of osteoarthritis.

We did not evaluate functional improvement in this meta-analysis because functional status was not measured in some trials and the assessment methods were too variable in the trials that did assess functional status. Publication bias, or the possibility that unpublished data would contradict the results of published studies, is always a potential source of bias in meta-analysis. However, the Egger test was not statistically significant (6.5; 95% CI, –0.5, +13.5) suggesting that there is no publication bias.25

Finally, the presence of heterogeneity of results indicates there were important differences among the studies. Exclusion of clinical trials considered of poor quality diminished this heterogeneity substantially. Subanalysis restricted to good-quality studies supports the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis pain, although the effect size is smaller when one considers only the good quality studies.

There are 2 other potential limitations of this meta-analysis. Five studies allowed pain to be treated with analgesics such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs,12,13,16-18 and use of acetaminophen or NSAIDs may have altered the response to hyaluronic acid treatment. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed in only 2 studies (by Altman and Huskisson),16,18 wherein a post-hoc and “last observation carried forward” analysis showed a trend favoring hyaluronic acid. The treatment effects may have been smaller had the other trials used an intention to treat analysis.

This meta-analysis confirms that viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid is modestly effective in short term relief of pain in knee osteoarthritis. Our meta-analysis included only double-blinded, randomized trials published in English language in humans using VAS as the pain outcome measure, and our conclusions are very similar to those of Lo.2

Indications for use. Hyaluronic acid is helpful in relieving pain for carefully selected patients with knee osteoarthritis who have not responded to adequate use of systemic therapeutic agents, including acetaminophen, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors and topical agents, along with lifestyle modification such as weight reduction and exercise.

Patients should have a trial for at least three months of conservative therapy or be unable to tolerate NSAIDs before a decision to give 3- to 5-injection course with hyaluronic acid is made.

Hyaluronic acid may be an option when there is a need to delay knee surgery in middle-aged persons1 or for patients who have failed other treatments.

Time to pain relief. To improve adherence to treatment, tell patients receiving intra-articular hyaluronic acid that the benefits in pain reduction may not be noticeable until 5 to 10 weeks after the last injection.

Cost. Although the cost of hyaluronic acid treatment is covered by Medicare and most insurance plans for symptomatic osteoarthritis of knee, documentation in patient medical records should indicate the signs and symptoms supporting the diagnosis and functional impairment. Objective data to support a diagnosis of osteoarthritis such as x-ray, arthroscopy report, computed tomography scan, or magnetic resonance imaging should be available in the event of a review.

The cost of 1 hyaluronic acid (30 mg/mL) injection is approximately $230. Considering a course of 3 to 5 weekly knee injections, and adding other pharmacy, hospital, or clinic charges, the cost per treatment may exceed $1000 per knee.26,27 The cost-benefit of pain control with viscosupplementation must be carefully compared with other therapeutic agents and regimens currently available for knee osteoarthritis management.

FIGURE 3

Studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1)

Egger’s publication bias plot for the studies evaluated at outcome measurement time (week 1) not significant (+2.3, P=0.096, 95% CI: –0.5, +5.2).

Acknowledgments

Jeff Welge, PhD, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Center for Bio-statistical Services, for comments on final data analysis and presentation, Marie Marley, PhD for editing the manuscript, and Charity Noble for help in preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Arvind Modawal, MD, MPH, MRCGP, University of Cincinnati Department of Family Medicine/Geriatrics, PO Box 670582, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0582. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Cefalu CA, Waddell DS. Viscosupplementation: Treatment alternative for osteoarthritis of the knee. Geriatrics 1999;54:51-57.

2. Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T, Felson DT. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis. JAMA 2003;290:3115-3121.

3. Jones AC, Pattrick M, Doherty S, Doherty M. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid compared to intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide in inflammatory knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1995;3:269-273.

4. Graf J, Neusel E, Schneider E, Niethard FU. Intra-articular treatment with hyaluronic acid in osteoarthritis of the knee joint: a controlled clinical trial versus mucopolysaccharide polysulfuric acid ester. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1993;11:367-72.

5. Dougados M, Nguyen M, Listrat V, Amor B. High molecular weight sodium hyaluronate (hyalectin) in osteoarthritis of the knee: A one year placebo-controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1993;1:97-103.

6. Adams ME. An analysis of clinical studies of the use of cross-linked hyaluronan, hylan, in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Supp 1993;39:16-18.

7. Grecomoro G, Piccione F, Letizia G. Therapeutic synergism between hyaluronic acid and dexamethasone in the intra-articular treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a preliminary open study. Curr Med Res Opin 1992;13:49-55.

8. Leardini G, Mattara L, Franceschini M, Perbellini A. Intra-articular treatment of knee osteoarthritis. A comparative study between hyaluronic acid and 6-methyl prednisolone acetate. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1991;9:375-381.

9. Wu J, Shih L, Hsu H, Chen T. The double-blind test of sodium hyaluronate (ARTZ) on osteoarthritis knee. Chin Med J (Taipei) 1997;59:99-106.

10. Dixon AS, Jacoby RK, Berry H, Hamilton EB. Clinical trial of intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Curr Med Res Opin 1988;11:205-213.

11. Grecomoro G, Martorana U, Di Marco C. Intra-articular treatment with sodium hyaluronate in gonarthrosis: a controlled clinical trial versus placebo. Pharmather 1987;5:137-141.

12. Puhl W, Bernau A, Greiling H, Kopcke W, Pforringer W, Steck KJ. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate in osteoarthritis of the knee: a multicenter, double-blind study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1993;1:233-241.

13. Henderson EB, Smith EC, Pegley F, Blake DR. Intra-articular injections of 750 kD hyaluronan in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a randomized single centre double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 91 patients demonstrating lack of efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis 1994;53:529-554.

14. Scale D, Wobig M, Wolpert W. Viscosupplementation of osteoarthritic knees with Hylan: A treatment schedule study. Curr Ther Res 1994;55:220-232.

15. Lohmander LS, Dalen N, Englund G, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronan injections in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled multicentre trial. Hyaluronan Multicentre Trial Group [see comments]. Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:424-431.

16. Altman RD, Moskowitz R. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan®) in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol 1998;25:2203-2212.

17. Wobig M, Dickhut A, Maier R, Vetter G. Viscosupplementation with Hylan G-F-20: A 26-week controlled trial of efficacy and safety in the osteoarthritic knee. Clin Ther 1998;20:410-423.

18. Huskisson EC, Donnelly S. Hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology 1999;38:602-607.

19. Petrella RJ, DiSilvestro MD, Hildebrand C. Effects of hyaluronate sodium on pain and physical functioning in osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:292-298.

20. Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:769-773.

21. Chalmers TC, Smith H, Jr, Blackburn B, et al. A Method for Assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials 1981;2:31-49.

22. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-188.

23. Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D, Ancona-Berk VA, Chalmers TC. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 1987;316:450-455.

24. Galbraith R. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med 1988;7:889-894.

25. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-634.

26. CIGNA Government Services. Not otherwise classified drug fee schedule. Available at: www.cignamedicare.com/partb/fsch/2004/q2/noc.html. Accessed on June 20, 2005.

27. Empire Medicare Services. Local coverage determination. Hyaluronate polymers (Synvisc, Hyalgan) (A02-0011-R3). Available at: www.empiremedicare.com/Nyorkpolicya/policy/A02-0011-R_FINAL.htm.

28. Peyron JG, Balazs EA. Preliminary clinical assessment of Na-hyaluronate injection into human arthritic joints. Pathol Biol 1974;22:731-736.

1. Cefalu CA, Waddell DS. Viscosupplementation: Treatment alternative for osteoarthritis of the knee. Geriatrics 1999;54:51-57.

2. Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T, Felson DT. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis. JAMA 2003;290:3115-3121.

3. Jones AC, Pattrick M, Doherty S, Doherty M. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid compared to intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide in inflammatory knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1995;3:269-273.

4. Graf J, Neusel E, Schneider E, Niethard FU. Intra-articular treatment with hyaluronic acid in osteoarthritis of the knee joint: a controlled clinical trial versus mucopolysaccharide polysulfuric acid ester. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1993;11:367-72.

5. Dougados M, Nguyen M, Listrat V, Amor B. High molecular weight sodium hyaluronate (hyalectin) in osteoarthritis of the knee: A one year placebo-controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1993;1:97-103.

6. Adams ME. An analysis of clinical studies of the use of cross-linked hyaluronan, hylan, in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Supp 1993;39:16-18.

7. Grecomoro G, Piccione F, Letizia G. Therapeutic synergism between hyaluronic acid and dexamethasone in the intra-articular treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a preliminary open study. Curr Med Res Opin 1992;13:49-55.

8. Leardini G, Mattara L, Franceschini M, Perbellini A. Intra-articular treatment of knee osteoarthritis. A comparative study between hyaluronic acid and 6-methyl prednisolone acetate. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1991;9:375-381.

9. Wu J, Shih L, Hsu H, Chen T. The double-blind test of sodium hyaluronate (ARTZ) on osteoarthritis knee. Chin Med J (Taipei) 1997;59:99-106.

10. Dixon AS, Jacoby RK, Berry H, Hamilton EB. Clinical trial of intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Curr Med Res Opin 1988;11:205-213.

11. Grecomoro G, Martorana U, Di Marco C. Intra-articular treatment with sodium hyaluronate in gonarthrosis: a controlled clinical trial versus placebo. Pharmather 1987;5:137-141.

12. Puhl W, Bernau A, Greiling H, Kopcke W, Pforringer W, Steck KJ. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate in osteoarthritis of the knee: a multicenter, double-blind study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1993;1:233-241.

13. Henderson EB, Smith EC, Pegley F, Blake DR. Intra-articular injections of 750 kD hyaluronan in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a randomized single centre double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 91 patients demonstrating lack of efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis 1994;53:529-554.

14. Scale D, Wobig M, Wolpert W. Viscosupplementation of osteoarthritic knees with Hylan: A treatment schedule study. Curr Ther Res 1994;55:220-232.

15. Lohmander LS, Dalen N, Englund G, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronan injections in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled multicentre trial. Hyaluronan Multicentre Trial Group [see comments]. Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:424-431.

16. Altman RD, Moskowitz R. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan®) in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol 1998;25:2203-2212.

17. Wobig M, Dickhut A, Maier R, Vetter G. Viscosupplementation with Hylan G-F-20: A 26-week controlled trial of efficacy and safety in the osteoarthritic knee. Clin Ther 1998;20:410-423.

18. Huskisson EC, Donnelly S. Hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology 1999;38:602-607.

19. Petrella RJ, DiSilvestro MD, Hildebrand C. Effects of hyaluronate sodium on pain and physical functioning in osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:292-298.

20. Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:769-773.

21. Chalmers TC, Smith H, Jr, Blackburn B, et al. A Method for Assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials 1981;2:31-49.

22. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-188.

23. Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D, Ancona-Berk VA, Chalmers TC. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 1987;316:450-455.

24. Galbraith R. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med 1988;7:889-894.

25. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-634.

26. CIGNA Government Services. Not otherwise classified drug fee schedule. Available at: www.cignamedicare.com/partb/fsch/2004/q2/noc.html. Accessed on June 20, 2005.

27. Empire Medicare Services. Local coverage determination. Hyaluronate polymers (Synvisc, Hyalgan) (A02-0011-R3). Available at: www.empiremedicare.com/Nyorkpolicya/policy/A02-0011-R_FINAL.htm.

28. Peyron JG, Balazs EA. Preliminary clinical assessment of Na-hyaluronate injection into human arthritic joints. Pathol Biol 1974;22:731-736.