User login

Spondyloarthritis became, in 2009, a much better defined disease, and partly as a result it is something that physicians increasingly see the more they look for it. That’s especially true for peripheral spondyloarthritis, historically ill defined and rarely diagnosed.

The prevalence of recognized cases of peripheral spondyloarthritis (SpA) and its more common sister disease axial SpA began rising when the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society released new criteria in 2009 for diagnosing both axial and peripheral SpA. The consequence of the new peripheral SpA definitions has been increased diagnostic awareness over the ensuing 4 years.

"The nonaxial, nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA population is unique, and we increasingly find these patients as we have started to look for them," Seattle rheumatologist Dr. Philip Mease told me in June at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid.

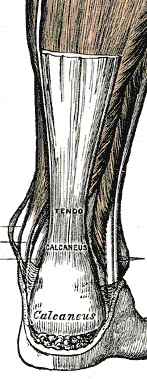

These patients often are initially misdiagnosed and unrecognized as peripheral SpA cases with presumed "fibromyalgia or nonspecific aches and pains" under the care of an orthopedist, physiatrist, or primary care physician. But more recently such patients "are starting to surface with evidence of elevated CRP [C-reactive protein] and inflammatory symptoms," including morning stiffness, back pain, and symptoms at the peripheral entheses that start at a relatively young age. Dr. Mease suggested that these "entry point" clinicians be on the lookout for "puzzlingly persistent pain in peripheral joint or tendon-insertion sites," along with subtle clues like an old episode of uveitis or a family history of psoriasis, all signals of a possible case of peripheral SpA. On further examination, patients with symptoms such as persistent Achilles tendonitis show elevated CRP levels, and an "MRI scan that lights up where the Achilles tendon inserts."

Dr. Mease told me that he sees growing awareness among primary care clinicians in the community about these symptoms and the fact that they flag an inflammatory, rheumatologic process that’s best managed by anti-inflammatory treatments, such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and newer drugs now receiving approval for rheumatic diseases.

"There is such a rising tide of interest in SpA in general," he said, a tide traceable back to the landmark definitions of 2009.

–By Mitchel L. Zoler

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Spondyloarthritis became, in 2009, a much better defined disease, and partly as a result it is something that physicians increasingly see the more they look for it. That’s especially true for peripheral spondyloarthritis, historically ill defined and rarely diagnosed.

The prevalence of recognized cases of peripheral spondyloarthritis (SpA) and its more common sister disease axial SpA began rising when the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society released new criteria in 2009 for diagnosing both axial and peripheral SpA. The consequence of the new peripheral SpA definitions has been increased diagnostic awareness over the ensuing 4 years.

"The nonaxial, nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA population is unique, and we increasingly find these patients as we have started to look for them," Seattle rheumatologist Dr. Philip Mease told me in June at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid.

These patients often are initially misdiagnosed and unrecognized as peripheral SpA cases with presumed "fibromyalgia or nonspecific aches and pains" under the care of an orthopedist, physiatrist, or primary care physician. But more recently such patients "are starting to surface with evidence of elevated CRP [C-reactive protein] and inflammatory symptoms," including morning stiffness, back pain, and symptoms at the peripheral entheses that start at a relatively young age. Dr. Mease suggested that these "entry point" clinicians be on the lookout for "puzzlingly persistent pain in peripheral joint or tendon-insertion sites," along with subtle clues like an old episode of uveitis or a family history of psoriasis, all signals of a possible case of peripheral SpA. On further examination, patients with symptoms such as persistent Achilles tendonitis show elevated CRP levels, and an "MRI scan that lights up where the Achilles tendon inserts."

Dr. Mease told me that he sees growing awareness among primary care clinicians in the community about these symptoms and the fact that they flag an inflammatory, rheumatologic process that’s best managed by anti-inflammatory treatments, such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and newer drugs now receiving approval for rheumatic diseases.

"There is such a rising tide of interest in SpA in general," he said, a tide traceable back to the landmark definitions of 2009.

–By Mitchel L. Zoler

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Spondyloarthritis became, in 2009, a much better defined disease, and partly as a result it is something that physicians increasingly see the more they look for it. That’s especially true for peripheral spondyloarthritis, historically ill defined and rarely diagnosed.

The prevalence of recognized cases of peripheral spondyloarthritis (SpA) and its more common sister disease axial SpA began rising when the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society released new criteria in 2009 for diagnosing both axial and peripheral SpA. The consequence of the new peripheral SpA definitions has been increased diagnostic awareness over the ensuing 4 years.

"The nonaxial, nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA population is unique, and we increasingly find these patients as we have started to look for them," Seattle rheumatologist Dr. Philip Mease told me in June at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in Madrid.

These patients often are initially misdiagnosed and unrecognized as peripheral SpA cases with presumed "fibromyalgia or nonspecific aches and pains" under the care of an orthopedist, physiatrist, or primary care physician. But more recently such patients "are starting to surface with evidence of elevated CRP [C-reactive protein] and inflammatory symptoms," including morning stiffness, back pain, and symptoms at the peripheral entheses that start at a relatively young age. Dr. Mease suggested that these "entry point" clinicians be on the lookout for "puzzlingly persistent pain in peripheral joint or tendon-insertion sites," along with subtle clues like an old episode of uveitis or a family history of psoriasis, all signals of a possible case of peripheral SpA. On further examination, patients with symptoms such as persistent Achilles tendonitis show elevated CRP levels, and an "MRI scan that lights up where the Achilles tendon inserts."

Dr. Mease told me that he sees growing awareness among primary care clinicians in the community about these symptoms and the fact that they flag an inflammatory, rheumatologic process that’s best managed by anti-inflammatory treatments, such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and newer drugs now receiving approval for rheumatic diseases.

"There is such a rising tide of interest in SpA in general," he said, a tide traceable back to the landmark definitions of 2009.

–By Mitchel L. Zoler

On Twitter @mitchelzoler