User login

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society names an Allergen of the Year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the Allergen of the Year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).In 2020, the American Contact Dermatitis Society chose isobornyl acrylate as the Allergen of the Year.1 Not only has isobornyl acrylate been implicated in an epidemic of contact allergy to diabetic devices, but it also illustrates the challenges of investigating contact allergy to medical devices in general.

What Is Isobornyl Acrylate?

Isobornyl acrylate, also known as the isobornyl ester of acrylic acid, is a chemical used in glues, adhesives, coatings, sealants, inks, and paints. Similar to other acrylates, such as those involved in gel nail treatments, it is photopolymerizable; that is, when exposed to UV light, it can transform from a liquid monomer into a hard polymer, contributing to its utility as an adhesive. Prior to its recent implication in diabetic device contact allergy, isobornyl acrylate was not thought to be a common skin sensitizer. In a 2013 Dutch study of patients with acrylate allergy, only 1 of 14 patients with a contact allergy to other acrylates had a positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate, which led the authors to conclude that adding it to their acrylate patch test series was not indicated.2

Isobornyl Acrylate in Diabetic Devices

Devices such as glucose monitoring systems and insulin pumps are used by millions of patients with diabetes worldwide. Not only are continuous glucose monitoring devices more convenient than self-monitoring of blood glucose, but they also are associated with a reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels and lower risk for hypoglycemia.3 However, these devices have been increasingly recognized as a source of irritant contact dermatitis and ACD.

Early cases of contact allergy to isobornyl acrylate in diabetic devices were reported in 1995 when 2 Belgian patients using insulin pumps developed ACD.4 The patients had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum and other allergens including acrylates. In addition, patch testing with plastic scrapings from their insulin pumps also was positive, and it was determined that the glue affixing the needle to the plastic had diffused into the plastic. The patients were switched to insulin pumps produced by heat staking instead of glue, and their symptoms resolved. In retrospect, this case series may seem prescient, as it was written 2 decades before isobornyl acrylate became recognized as a widespread cause of ACD in users of diabetic devices. Admittedly, other acrylate components of the glue also were positive on patch testing in these patients, so it was not until much later that the focus turned more exclusively to isobornyl acrylate.4

Similar to the insulin pumps in the 1995 Belgian series, diffusion of glue to other parts of modern glucose sensors also appears to cause isobornyl acrylate contact allergy. This theory was supported by a 2017 study from Belgian and Swedish investigators in which gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was used to identify concentrations of isobornyl acrylate in various components of a popular continuous glucose monitoring sensor.5 The concentration of isobornyl acrylate was approximately 100-fold higher at the site where the top and bottom plastic components of the sensor were joined as compared to the adhesive patch in contact with the patient’s skin. Therefore, the adhesive patch itself was not the source of the isobornyl acrylate exposure; rather, the isobornyl acrylate diffused into the adhesive patch from the glue used to join the components of the sensor together.5 One ramification is that patients with diabetic device contact allergy can have a false-negative patch test result if the adhesive patch is tested by itself, whereas they may react to patch testing with the whole sensor or an acetonic extract thereof.

Frequency of Sensitization to Isobornyl Acrylate

It is difficult to estimate the frequency of sensitization to isobornyl acrylate among users of diabetic devices, in part because those with mild allergy may not seek medical treatment. Nevertheless, there are studies that demonstrate a high prevalence of sensitization among users with suspected allergy. In a 2019 Finnish study of 6567 patients using an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor, 63 were patch tested for suspected ACD.6 Of these 63 patients, 51 (81%) had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum. These findings were consistent with the original 2017 study from Belgium and Sweden, in which 10 of 11 (91%) patients who used an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor and had suspected contact allergy had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum compared to no positive reactions in the 14 control patients.5 Given that there are more than 1.5 million users of this isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor across 46 countries,7 it requires no stretch of the imagination to understand why investigators refer to isobornyl acrylate allergy as an epidemic, even if only a small percentage of users are sensitized to the device.

The Journey to Discover Isobornyl Acrylate as a Culprit Allergen

Similar to the discoveries of radiography and penicillin, the discovery of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen in a modern glucose sensor was purely accidental. In 2016, a 9-year-old boy with diabetes presented to a Belgian dermatology department with ACD to a glucose sensor.1 A patch test nurse serendipitously applied isobornyl acrylate—0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% in petrolatum—which was not intended to be applied as part of the typical acrylate series. The only positive patch test reactions in this patient were to isobornyl acrylate at all 3 concentrations. This lucky error inspired isobornyl acrylate to be tested at multiple other dermatology departments in Europe in patients with ACD to their glucose sensors, leading to its discovery as a culprit allergen.1

One challenge facing investigators was obtaining information and materials from the diabetic device industry. Medical device manufacturers are not required to disclose chemicals present in a device on its label.8 Therefore, for patients or investigators to determine whether a potential allergen is present in a given device, they must request that information from the manufacturer, which can be a time-consuming and frustrating effort. Luckily, investigators collaborated with one another, and Belgian investigators suggested that Swedish investigators performing chemical analyses on a glucose monitoring device should focus on isobornyl acrylate, which enabled its detection in an extract from the device.5

Testing for Isobornyl Acrylate Allergy in Your Clinic

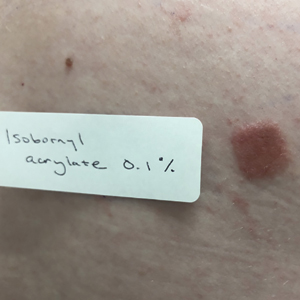

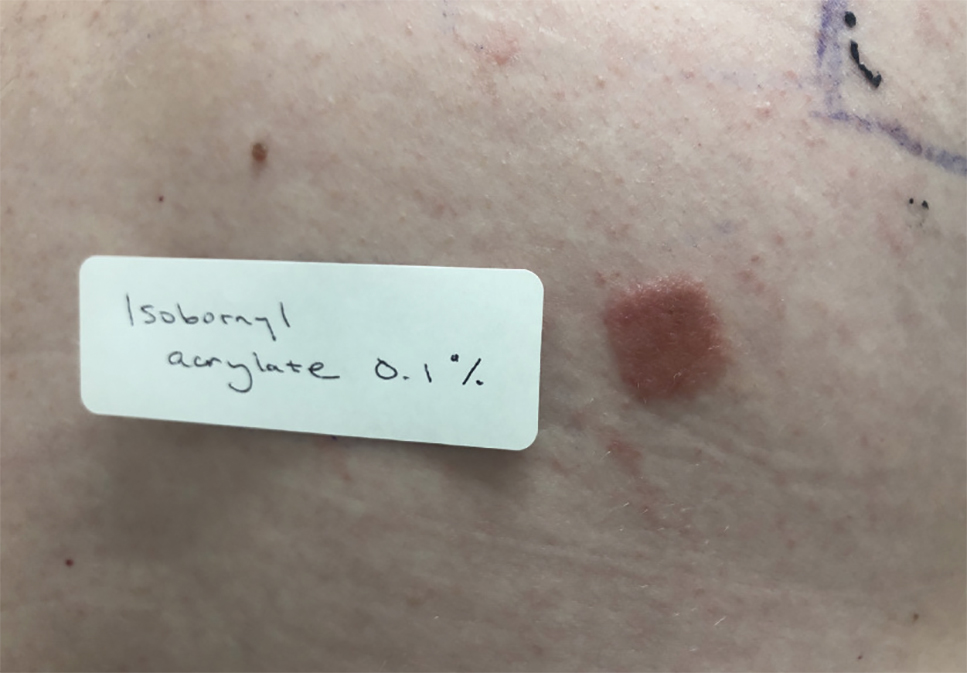

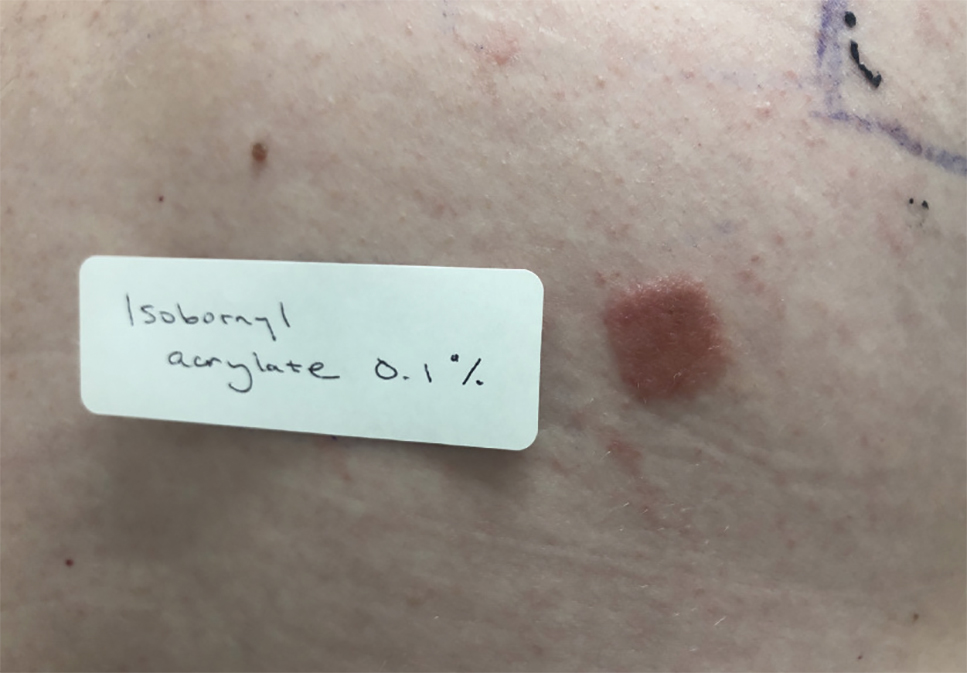

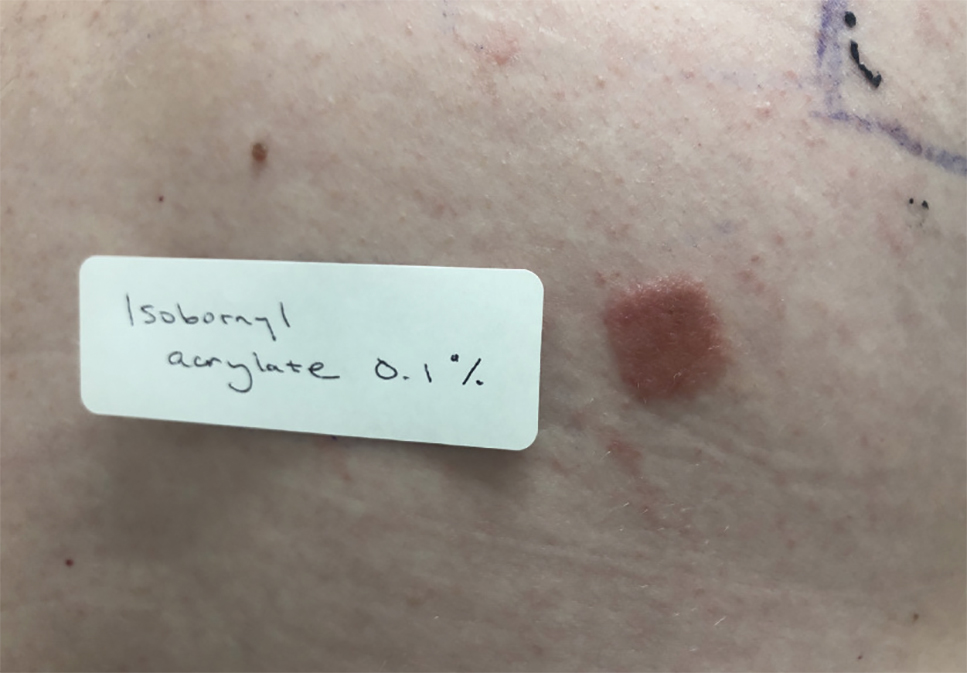

Patients with suspected ACD to a diabetic device—insulin pump or glucose sensor—should be patch tested with isobornyl acrylate, in addition to other previously reported allergens. The vehicle typically is petrolatum, and the commonly tested concentration is 0.1%. Testing with lower concentrations such as 0.01% can result in false-negative reactions,9 and testing at higher concentrations such as 0.3% can result in irritant skin reactions.2 Isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum currently is available from one commercial allergen supplier (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). A positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is shown in the Figure.

Management of Diabetic Device ACD

For patients with diabetic device ACD, there are several strategies that can reduce direct contact between the device and the patient’s skin. Methods that have been tried with varying success to allow patients to continue using their glucose sensors include barrier sprays (eg, Cavilon [3M], Silesse Skin Barrier [ConvaTec]); barrier pads (eg, Compeed [HRA Pharma], Surround skin protectors [Eakin], DuoDERM dressings [ConvaTec], Tegaderm dressings [3M]); and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. Nevertheless, a 2019 Finnish study showed that only 14 of 63 (22%) patients with ACD to their isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor were able to continue using the device, with all 14 requiring use of a barrier agent. Despite using the barrier agent, 13 (93%) of these patients had residual dermatitis.6 There also is concern that use of barrier methods might hamper the proper functioning of glucose sensors and related devices.

Patients with known isobornyl acrylate contact allergy also may switch to a different diabetic device. A 2019 German study showed that in 5 patients with isobornyl acrylate ACD, none had reactions to the one particular system that has been shown by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to not contain isobornyl acrylate.10 However, as a word of caution, the same device also has been associated with ACD11,12 but has been resolved by using heat staking during the production process.13 As manufacturers update device components, identification of other isobornyl acrylate–free devices may require a degree of trial and error, as neither isobornyl acrylate nor any other potential allergen is listed on device labels.

Final Interpretation

Isobornyl acrylate is not a common sensitizer in general patch test populations but is a recently identified major culprit in ACD to diabetic devices. Patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is not necessary in standard screening panels but should be considered in patients with suspected ACD to glucose sensors or insulin pumps. If a patient with ACD wants to continue to experience the convenience provided by a diabetic device, options include using topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though none of these methods are foolproof. Hopefully, the identification of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen will help to improve the lives of patients who use diabetic devices worldwide.

- Aerts O, Herman A, Mowitz M, et al. Isobornyl acrylate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:4-12.

- Christoffers WA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar ML. Two decades of occupational (meth)acrylate patch test results and focus on isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:86-92.

- Pickup JC, Freeman SC, Sutton AJ. Glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes during real time continuous glucose monitoring compared with self monitoring of blood glucose: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials using individual patient data. BMJ. 2011;343:d3805.

- Busschots AM, Meuleman V, Poesen N, et al. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:205-206.

- Herman A, Aerts O, Baeck M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:367-373.

- Hyry HSI, Liippo JP, Virtanen HM. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:161-166.

- Abbott’s Revolutionary FreeStyle® Libre system now reimbursed in the two largest provinces in Canada [press release]. Abbott Park, IL: Abbott; September 13, 2019. https://abbott.mediaroom.com/2019-09-13-Abbotts-Revolutionary-FreeStyle-R-Libre-System-Now-Reimbursed-in-the-Two-Largest-Provinces-in-Canada. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- Herman A, Goossens A. The need to disclose the composition of medical devices at the European level. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:159-160.

- Raison-Peyron N, Mowitz M, Bonardel N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in OmniPod, an innovative tubeless insulin pump. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:76-80.

- Oppel E, Kamann S, Reichl FX, et al. The Dexcom glucose monitoring system—an isobornyl acrylate-free alternative for diabetic patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:32-36.

- Peeters C, Herman A, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by 2-ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in glucose sensor sets in two diabetic adults. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:426-429.

- Aschenbeck KA, Hylwa SA. A diabetic’s allergy: ethyl cyanoacrylate in glucose sensor adhesive. Dermatitis. 2017;28:289-291.

- Gisin V, Chan A, Welsh B. Manufacturing process changes and reduced skin irritations of an adhesive patch used for continuous glucose monitoring devices. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:725-726.

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society names an Allergen of the Year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the Allergen of the Year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).In 2020, the American Contact Dermatitis Society chose isobornyl acrylate as the Allergen of the Year.1 Not only has isobornyl acrylate been implicated in an epidemic of contact allergy to diabetic devices, but it also illustrates the challenges of investigating contact allergy to medical devices in general.

What Is Isobornyl Acrylate?

Isobornyl acrylate, also known as the isobornyl ester of acrylic acid, is a chemical used in glues, adhesives, coatings, sealants, inks, and paints. Similar to other acrylates, such as those involved in gel nail treatments, it is photopolymerizable; that is, when exposed to UV light, it can transform from a liquid monomer into a hard polymer, contributing to its utility as an adhesive. Prior to its recent implication in diabetic device contact allergy, isobornyl acrylate was not thought to be a common skin sensitizer. In a 2013 Dutch study of patients with acrylate allergy, only 1 of 14 patients with a contact allergy to other acrylates had a positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate, which led the authors to conclude that adding it to their acrylate patch test series was not indicated.2

Isobornyl Acrylate in Diabetic Devices

Devices such as glucose monitoring systems and insulin pumps are used by millions of patients with diabetes worldwide. Not only are continuous glucose monitoring devices more convenient than self-monitoring of blood glucose, but they also are associated with a reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels and lower risk for hypoglycemia.3 However, these devices have been increasingly recognized as a source of irritant contact dermatitis and ACD.

Early cases of contact allergy to isobornyl acrylate in diabetic devices were reported in 1995 when 2 Belgian patients using insulin pumps developed ACD.4 The patients had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum and other allergens including acrylates. In addition, patch testing with plastic scrapings from their insulin pumps also was positive, and it was determined that the glue affixing the needle to the plastic had diffused into the plastic. The patients were switched to insulin pumps produced by heat staking instead of glue, and their symptoms resolved. In retrospect, this case series may seem prescient, as it was written 2 decades before isobornyl acrylate became recognized as a widespread cause of ACD in users of diabetic devices. Admittedly, other acrylate components of the glue also were positive on patch testing in these patients, so it was not until much later that the focus turned more exclusively to isobornyl acrylate.4

Similar to the insulin pumps in the 1995 Belgian series, diffusion of glue to other parts of modern glucose sensors also appears to cause isobornyl acrylate contact allergy. This theory was supported by a 2017 study from Belgian and Swedish investigators in which gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was used to identify concentrations of isobornyl acrylate in various components of a popular continuous glucose monitoring sensor.5 The concentration of isobornyl acrylate was approximately 100-fold higher at the site where the top and bottom plastic components of the sensor were joined as compared to the adhesive patch in contact with the patient’s skin. Therefore, the adhesive patch itself was not the source of the isobornyl acrylate exposure; rather, the isobornyl acrylate diffused into the adhesive patch from the glue used to join the components of the sensor together.5 One ramification is that patients with diabetic device contact allergy can have a false-negative patch test result if the adhesive patch is tested by itself, whereas they may react to patch testing with the whole sensor or an acetonic extract thereof.

Frequency of Sensitization to Isobornyl Acrylate

It is difficult to estimate the frequency of sensitization to isobornyl acrylate among users of diabetic devices, in part because those with mild allergy may not seek medical treatment. Nevertheless, there are studies that demonstrate a high prevalence of sensitization among users with suspected allergy. In a 2019 Finnish study of 6567 patients using an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor, 63 were patch tested for suspected ACD.6 Of these 63 patients, 51 (81%) had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum. These findings were consistent with the original 2017 study from Belgium and Sweden, in which 10 of 11 (91%) patients who used an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor and had suspected contact allergy had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum compared to no positive reactions in the 14 control patients.5 Given that there are more than 1.5 million users of this isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor across 46 countries,7 it requires no stretch of the imagination to understand why investigators refer to isobornyl acrylate allergy as an epidemic, even if only a small percentage of users are sensitized to the device.

The Journey to Discover Isobornyl Acrylate as a Culprit Allergen

Similar to the discoveries of radiography and penicillin, the discovery of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen in a modern glucose sensor was purely accidental. In 2016, a 9-year-old boy with diabetes presented to a Belgian dermatology department with ACD to a glucose sensor.1 A patch test nurse serendipitously applied isobornyl acrylate—0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% in petrolatum—which was not intended to be applied as part of the typical acrylate series. The only positive patch test reactions in this patient were to isobornyl acrylate at all 3 concentrations. This lucky error inspired isobornyl acrylate to be tested at multiple other dermatology departments in Europe in patients with ACD to their glucose sensors, leading to its discovery as a culprit allergen.1

One challenge facing investigators was obtaining information and materials from the diabetic device industry. Medical device manufacturers are not required to disclose chemicals present in a device on its label.8 Therefore, for patients or investigators to determine whether a potential allergen is present in a given device, they must request that information from the manufacturer, which can be a time-consuming and frustrating effort. Luckily, investigators collaborated with one another, and Belgian investigators suggested that Swedish investigators performing chemical analyses on a glucose monitoring device should focus on isobornyl acrylate, which enabled its detection in an extract from the device.5

Testing for Isobornyl Acrylate Allergy in Your Clinic

Patients with suspected ACD to a diabetic device—insulin pump or glucose sensor—should be patch tested with isobornyl acrylate, in addition to other previously reported allergens. The vehicle typically is petrolatum, and the commonly tested concentration is 0.1%. Testing with lower concentrations such as 0.01% can result in false-negative reactions,9 and testing at higher concentrations such as 0.3% can result in irritant skin reactions.2 Isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum currently is available from one commercial allergen supplier (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). A positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is shown in the Figure.

Management of Diabetic Device ACD

For patients with diabetic device ACD, there are several strategies that can reduce direct contact between the device and the patient’s skin. Methods that have been tried with varying success to allow patients to continue using their glucose sensors include barrier sprays (eg, Cavilon [3M], Silesse Skin Barrier [ConvaTec]); barrier pads (eg, Compeed [HRA Pharma], Surround skin protectors [Eakin], DuoDERM dressings [ConvaTec], Tegaderm dressings [3M]); and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. Nevertheless, a 2019 Finnish study showed that only 14 of 63 (22%) patients with ACD to their isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor were able to continue using the device, with all 14 requiring use of a barrier agent. Despite using the barrier agent, 13 (93%) of these patients had residual dermatitis.6 There also is concern that use of barrier methods might hamper the proper functioning of glucose sensors and related devices.

Patients with known isobornyl acrylate contact allergy also may switch to a different diabetic device. A 2019 German study showed that in 5 patients with isobornyl acrylate ACD, none had reactions to the one particular system that has been shown by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to not contain isobornyl acrylate.10 However, as a word of caution, the same device also has been associated with ACD11,12 but has been resolved by using heat staking during the production process.13 As manufacturers update device components, identification of other isobornyl acrylate–free devices may require a degree of trial and error, as neither isobornyl acrylate nor any other potential allergen is listed on device labels.

Final Interpretation

Isobornyl acrylate is not a common sensitizer in general patch test populations but is a recently identified major culprit in ACD to diabetic devices. Patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is not necessary in standard screening panels but should be considered in patients with suspected ACD to glucose sensors or insulin pumps. If a patient with ACD wants to continue to experience the convenience provided by a diabetic device, options include using topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though none of these methods are foolproof. Hopefully, the identification of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen will help to improve the lives of patients who use diabetic devices worldwide.

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society names an Allergen of the Year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the Allergen of the Year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).In 2020, the American Contact Dermatitis Society chose isobornyl acrylate as the Allergen of the Year.1 Not only has isobornyl acrylate been implicated in an epidemic of contact allergy to diabetic devices, but it also illustrates the challenges of investigating contact allergy to medical devices in general.

What Is Isobornyl Acrylate?

Isobornyl acrylate, also known as the isobornyl ester of acrylic acid, is a chemical used in glues, adhesives, coatings, sealants, inks, and paints. Similar to other acrylates, such as those involved in gel nail treatments, it is photopolymerizable; that is, when exposed to UV light, it can transform from a liquid monomer into a hard polymer, contributing to its utility as an adhesive. Prior to its recent implication in diabetic device contact allergy, isobornyl acrylate was not thought to be a common skin sensitizer. In a 2013 Dutch study of patients with acrylate allergy, only 1 of 14 patients with a contact allergy to other acrylates had a positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate, which led the authors to conclude that adding it to their acrylate patch test series was not indicated.2

Isobornyl Acrylate in Diabetic Devices

Devices such as glucose monitoring systems and insulin pumps are used by millions of patients with diabetes worldwide. Not only are continuous glucose monitoring devices more convenient than self-monitoring of blood glucose, but they also are associated with a reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels and lower risk for hypoglycemia.3 However, these devices have been increasingly recognized as a source of irritant contact dermatitis and ACD.

Early cases of contact allergy to isobornyl acrylate in diabetic devices were reported in 1995 when 2 Belgian patients using insulin pumps developed ACD.4 The patients had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum and other allergens including acrylates. In addition, patch testing with plastic scrapings from their insulin pumps also was positive, and it was determined that the glue affixing the needle to the plastic had diffused into the plastic. The patients were switched to insulin pumps produced by heat staking instead of glue, and their symptoms resolved. In retrospect, this case series may seem prescient, as it was written 2 decades before isobornyl acrylate became recognized as a widespread cause of ACD in users of diabetic devices. Admittedly, other acrylate components of the glue also were positive on patch testing in these patients, so it was not until much later that the focus turned more exclusively to isobornyl acrylate.4

Similar to the insulin pumps in the 1995 Belgian series, diffusion of glue to other parts of modern glucose sensors also appears to cause isobornyl acrylate contact allergy. This theory was supported by a 2017 study from Belgian and Swedish investigators in which gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was used to identify concentrations of isobornyl acrylate in various components of a popular continuous glucose monitoring sensor.5 The concentration of isobornyl acrylate was approximately 100-fold higher at the site where the top and bottom plastic components of the sensor were joined as compared to the adhesive patch in contact with the patient’s skin. Therefore, the adhesive patch itself was not the source of the isobornyl acrylate exposure; rather, the isobornyl acrylate diffused into the adhesive patch from the glue used to join the components of the sensor together.5 One ramification is that patients with diabetic device contact allergy can have a false-negative patch test result if the adhesive patch is tested by itself, whereas they may react to patch testing with the whole sensor or an acetonic extract thereof.

Frequency of Sensitization to Isobornyl Acrylate

It is difficult to estimate the frequency of sensitization to isobornyl acrylate among users of diabetic devices, in part because those with mild allergy may not seek medical treatment. Nevertheless, there are studies that demonstrate a high prevalence of sensitization among users with suspected allergy. In a 2019 Finnish study of 6567 patients using an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor, 63 were patch tested for suspected ACD.6 Of these 63 patients, 51 (81%) had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum. These findings were consistent with the original 2017 study from Belgium and Sweden, in which 10 of 11 (91%) patients who used an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor and had suspected contact allergy had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum compared to no positive reactions in the 14 control patients.5 Given that there are more than 1.5 million users of this isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor across 46 countries,7 it requires no stretch of the imagination to understand why investigators refer to isobornyl acrylate allergy as an epidemic, even if only a small percentage of users are sensitized to the device.

The Journey to Discover Isobornyl Acrylate as a Culprit Allergen

Similar to the discoveries of radiography and penicillin, the discovery of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen in a modern glucose sensor was purely accidental. In 2016, a 9-year-old boy with diabetes presented to a Belgian dermatology department with ACD to a glucose sensor.1 A patch test nurse serendipitously applied isobornyl acrylate—0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% in petrolatum—which was not intended to be applied as part of the typical acrylate series. The only positive patch test reactions in this patient were to isobornyl acrylate at all 3 concentrations. This lucky error inspired isobornyl acrylate to be tested at multiple other dermatology departments in Europe in patients with ACD to their glucose sensors, leading to its discovery as a culprit allergen.1

One challenge facing investigators was obtaining information and materials from the diabetic device industry. Medical device manufacturers are not required to disclose chemicals present in a device on its label.8 Therefore, for patients or investigators to determine whether a potential allergen is present in a given device, they must request that information from the manufacturer, which can be a time-consuming and frustrating effort. Luckily, investigators collaborated with one another, and Belgian investigators suggested that Swedish investigators performing chemical analyses on a glucose monitoring device should focus on isobornyl acrylate, which enabled its detection in an extract from the device.5

Testing for Isobornyl Acrylate Allergy in Your Clinic

Patients with suspected ACD to a diabetic device—insulin pump or glucose sensor—should be patch tested with isobornyl acrylate, in addition to other previously reported allergens. The vehicle typically is petrolatum, and the commonly tested concentration is 0.1%. Testing with lower concentrations such as 0.01% can result in false-negative reactions,9 and testing at higher concentrations such as 0.3% can result in irritant skin reactions.2 Isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum currently is available from one commercial allergen supplier (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). A positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is shown in the Figure.

Management of Diabetic Device ACD

For patients with diabetic device ACD, there are several strategies that can reduce direct contact between the device and the patient’s skin. Methods that have been tried with varying success to allow patients to continue using their glucose sensors include barrier sprays (eg, Cavilon [3M], Silesse Skin Barrier [ConvaTec]); barrier pads (eg, Compeed [HRA Pharma], Surround skin protectors [Eakin], DuoDERM dressings [ConvaTec], Tegaderm dressings [3M]); and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. Nevertheless, a 2019 Finnish study showed that only 14 of 63 (22%) patients with ACD to their isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor were able to continue using the device, with all 14 requiring use of a barrier agent. Despite using the barrier agent, 13 (93%) of these patients had residual dermatitis.6 There also is concern that use of barrier methods might hamper the proper functioning of glucose sensors and related devices.

Patients with known isobornyl acrylate contact allergy also may switch to a different diabetic device. A 2019 German study showed that in 5 patients with isobornyl acrylate ACD, none had reactions to the one particular system that has been shown by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to not contain isobornyl acrylate.10 However, as a word of caution, the same device also has been associated with ACD11,12 but has been resolved by using heat staking during the production process.13 As manufacturers update device components, identification of other isobornyl acrylate–free devices may require a degree of trial and error, as neither isobornyl acrylate nor any other potential allergen is listed on device labels.

Final Interpretation

Isobornyl acrylate is not a common sensitizer in general patch test populations but is a recently identified major culprit in ACD to diabetic devices. Patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is not necessary in standard screening panels but should be considered in patients with suspected ACD to glucose sensors or insulin pumps. If a patient with ACD wants to continue to experience the convenience provided by a diabetic device, options include using topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though none of these methods are foolproof. Hopefully, the identification of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen will help to improve the lives of patients who use diabetic devices worldwide.

- Aerts O, Herman A, Mowitz M, et al. Isobornyl acrylate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:4-12.

- Christoffers WA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar ML. Two decades of occupational (meth)acrylate patch test results and focus on isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:86-92.

- Pickup JC, Freeman SC, Sutton AJ. Glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes during real time continuous glucose monitoring compared with self monitoring of blood glucose: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials using individual patient data. BMJ. 2011;343:d3805.

- Busschots AM, Meuleman V, Poesen N, et al. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:205-206.

- Herman A, Aerts O, Baeck M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:367-373.

- Hyry HSI, Liippo JP, Virtanen HM. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:161-166.

- Abbott’s Revolutionary FreeStyle® Libre system now reimbursed in the two largest provinces in Canada [press release]. Abbott Park, IL: Abbott; September 13, 2019. https://abbott.mediaroom.com/2019-09-13-Abbotts-Revolutionary-FreeStyle-R-Libre-System-Now-Reimbursed-in-the-Two-Largest-Provinces-in-Canada. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- Herman A, Goossens A. The need to disclose the composition of medical devices at the European level. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:159-160.

- Raison-Peyron N, Mowitz M, Bonardel N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in OmniPod, an innovative tubeless insulin pump. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:76-80.

- Oppel E, Kamann S, Reichl FX, et al. The Dexcom glucose monitoring system—an isobornyl acrylate-free alternative for diabetic patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:32-36.

- Peeters C, Herman A, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by 2-ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in glucose sensor sets in two diabetic adults. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:426-429.

- Aschenbeck KA, Hylwa SA. A diabetic’s allergy: ethyl cyanoacrylate in glucose sensor adhesive. Dermatitis. 2017;28:289-291.

- Gisin V, Chan A, Welsh B. Manufacturing process changes and reduced skin irritations of an adhesive patch used for continuous glucose monitoring devices. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:725-726.

- Aerts O, Herman A, Mowitz M, et al. Isobornyl acrylate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:4-12.

- Christoffers WA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar ML. Two decades of occupational (meth)acrylate patch test results and focus on isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:86-92.

- Pickup JC, Freeman SC, Sutton AJ. Glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes during real time continuous glucose monitoring compared with self monitoring of blood glucose: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials using individual patient data. BMJ. 2011;343:d3805.

- Busschots AM, Meuleman V, Poesen N, et al. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:205-206.

- Herman A, Aerts O, Baeck M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:367-373.

- Hyry HSI, Liippo JP, Virtanen HM. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:161-166.

- Abbott’s Revolutionary FreeStyle® Libre system now reimbursed in the two largest provinces in Canada [press release]. Abbott Park, IL: Abbott; September 13, 2019. https://abbott.mediaroom.com/2019-09-13-Abbotts-Revolutionary-FreeStyle-R-Libre-System-Now-Reimbursed-in-the-Two-Largest-Provinces-in-Canada. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- Herman A, Goossens A. The need to disclose the composition of medical devices at the European level. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:159-160.

- Raison-Peyron N, Mowitz M, Bonardel N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in OmniPod, an innovative tubeless insulin pump. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:76-80.

- Oppel E, Kamann S, Reichl FX, et al. The Dexcom glucose monitoring system—an isobornyl acrylate-free alternative for diabetic patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:32-36.

- Peeters C, Herman A, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by 2-ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in glucose sensor sets in two diabetic adults. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:426-429.

- Aschenbeck KA, Hylwa SA. A diabetic’s allergy: ethyl cyanoacrylate in glucose sensor adhesive. Dermatitis. 2017;28:289-291.

- Gisin V, Chan A, Welsh B. Manufacturing process changes and reduced skin irritations of an adhesive patch used for continuous glucose monitoring devices. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:725-726.

Practice Points

- In patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to a diabetic device, patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum should be considered.

- If patients with ACD to their diabetic device want to continue using the device, options include utilizing topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though these steps may not be effective for every patient.