User login

The literature includes only 2 case reports of bony avulsion fracture of the origin of the brachioradialis1,2 and, up until now, no case reports of isolated avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis origins from the lateral epicondyle and lateral supracondylar ridge. In this article, we report the case of a 31-year-old man who sustained this injury during a fall onto his outstretched right hand, and we present our surgical repair technique. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 31-year-old right hand–dominant garbage truck worker sustained a right elbow injury and presented 2 months later. He described slipping and falling onto his outstretched right hand while doing his work. He could not describe the exact mechanism or action or position of the arm at time of impact but thought he tried to catch himself on the truck during the fall. At time of injury, he had immediate pain and swelling to the lateral aspect of the right elbow and difficulty when he attempted lifting. He denied antecedent elbow symptoms before the injury. After evaluation by an outside occupational medicine physician, he engaged in treatment consisting of activity modification and physical therapy, including range-of-motion (ROM) exercises and iontophoresis. This course of management failed to completely relieve his symptoms, and he was unable to return to work.

The patient presented to our institution 9 weeks after injury with complaints of pain along the lateral aspect of the elbow, painful flexion-extension, and continued swelling. The pain had been unrelieved with anti-inflammatory medications and opioids. Physical examination revealed tenderness and swelling along the lateral epicondyle and extensor mass of the right elbow. The patient had tenderness, marked weakness, and a palpable soft-tissue defect at the origin of the extensor mass with resisted extension of the wrist (Figure 1). Elbow ROM was from 20° to 120° of flexion, 60° of pronation, and 60° of supination. No varus or valgus instability was present about the elbow. Radiographs did not show any fracture or dislocation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not definitively show extensor tendon avulsion but did identify signal change of the common extensor tendon (Figures 2A, 2B). Advanced imaging was inconclusive, but, given the patient’s history and physical examination findings, he was diagnosed with an avulsion injury of the origin of the extensor mass of the right elbow.

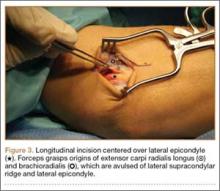

The patient was brought to the operating room, administered general anesthesia, and placed supine on the operating table with a tourniquet on the upper arm. A lateral 4.5-cm incision was made centered over the lateral epicondyle. The origin of the extensor mass was exposed, and isolated avulsions of the extensor carpi radialis longus and the brachioradialis were identified (Figures 3, 4). Underlying the avulsed sleeve of tissue, the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis was found intact. The lateral supracondylar ridge and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus were débrided, and 3 transosseous holes were drilled (using a 2.3-mm bit) through the lateral epicondyle. Four Mason-Allen sutures were placed into the tendon of the common extensor origin using No. 2 braided polyester suture (Ethibond Excel, Ethicon) (Figure 5). The tendon was reduced down to the native footprint, and the sutures were passed through the drill holes and tied down securely (Figure 6). The skin was then closed using layered 4-0 absorbable monofilament suture (Monocryl, Ethicon). The patient was placed in a posterior mold plaster splint with 90° of elbow flexion and with the wrist in 30° of extension.

On postoperative day 3, the patient was seen for a wound check and was placed in a long-arm fiberglass cast (90° of elbow flexion, forearm in neutral, 25° of wrist extension) for immobilization. One week after surgery, he was transitioned to a removable thermoplastic splint, and physical therapy for ROM was initiated. He was allowed therapist-guided active extension of the elbow and flexion of the wrist but was restricted to passive flexion of the elbow and extension of the wrist. Seven weeks after surgery, passive ROM about the elbow was measured, and he was found to have 120° of flexion, 0° extension, 80° pronation, and 80° supination. At 12 weeks, the physical therapy regimen was advanced to include muscle strengthening and active wrist extension and elbow flexion. At 16 weeks, the wrist extensors demonstrated 5/5 strength (Medical Research Council grading system), and the patient was cleared for full activity and weight-bearing without restriction. He returned to work pain-free and without restrictions 18 weeks after surgery. At 2-year follow-up, he had a Mayo performance elbow score of 100 and an Oxford elbow score of 48.3,4 He had full active ROM, full strength, and no subjective pain and was back doing heavy lifting at his job.

Discussion

The brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and extensor carpi radialis brevis originate from the anterolateral aspect of the lateral column of the distal humeral metaphysis and form the dorsal mobile wad. The origin of the brachioradialis is about 7 cm in length and begins about 10 to 11 cm above the elbow.5 The origin and insertions of the mobile wad, specifically the brachioradialis, provide a tremendous mechanical advantage with respect to elbow flexion against resistance, particularly with the forearm in the pronated and semipronated positions.6 With the elbow in 30° of flexion, a force 3 times the body weight can be encountered during strenuous lifting.6,7 We hypothesized these large forces likely led to this injury pattern in the patient we have described.

The literature includes 2 case reports of avulsion fracture of the brachioradialis muscle from its origin on the lateral supracondylar humeral ridge.1,2 To our knowledge, however, there have been no reports of pure avulsion. In our patient’s case, there was no bony fracture, but rather avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis at their origin, with the underlying fibers of the extensor carpi radialis brevis remaining in continuity. Because of the rarity of this injury pattern, there was a significant delay in diagnosis. On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for lateral elbow pain and tenderness included occult fracture, intracapsular plica, osteochondritis dissecans lesion, radial tunnel syndrome, lateral or posterolateral instability, and lateral epicondylitis. Given the absence of antecedent elbow symptoms before the injury, the dynamic soft-tissue asymmetry of the mobile wad with wrist extension, and the palpable soft-tissue defect, we thought the presentation was inconsistent with a simple inflammatory or overuse syndrome, such as lateral epicondylitis. In addition, the physical examination findings were inconsistent with radial tunnel syndrome or disruption of the lateral collateral ligament complex. Elbow MRI did not show an occult fracture, plica, or osteochondritis dissecans lesion but did reveal joint effusion and signal change in the common extensor tendon origin. Interestingly, MRI did not definitively show a tear of the mobile wad. This may be explained by the fact that the fibers of the underlying extensor carpi radialis brevis remained intact. Also potentially involved are the static nature of MRI and potentially suboptimal sequencing and axis of acquisition resulting from the relative infrequency of imaging this joint at certain health care institutions. Our case demonstrates the limitations of MRI in this setting and highlights the need for a detailed history and thorough physical examination for diagnosis.

Funk and colleagues8 used electromyography (EMG) to study the activity of the elbow musculature in uninjured subjects. EMG data were obtained with the elbow joint subjected to resisted flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. During resisted elbow flexion, there was an increasing amount of activity in the extensor carpi radialis with larger angles of elbow flexion. In addition, the brachioradialis demonstrated the most muscle activity of any of the elbow flexors with 90° or more of elbow flexion and forearm pronation, as opposed to other positions in which the brachialis was the primary flexor. For this reason, we hypothesized that our patient’s forearm was pronated and his elbow flexed to 90° or more when he braced for impact. The ensuing injury resulted from a violent eccentric contraction that caused extensive rupture of the lateral elbow musculature from its broad origin. With the forearm in supination or neutral position, we would have expected a possible injury to the distal biceps as opposed to the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis.

In our patient, this injury caused much functional disability, especially with elbow flexion and wrist extension. We hypothesized that, for the muscles to function properly, anatomical restoration would have to be achieved at their known footprint to maintain their mechanical advantage. Therefore, surgical intervention was indicated in our patient, an active laborer. Given the absence of an osseous fracture fragment in this injury pattern, healing must occur at the bone–tendon interface. As tendinous healing is more tenuous and protracted than osseous healing, we preferred transosseous repair. We believed that better tendon-to-bone healing would be possible with drilled osseous tunnels rather than with suture anchors. New studies describing alternative successful methods of treatment would add to our limited body of knowledge regarding this rare injury.

Conclusion

This is the first report of avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis from their origins. Given the biomechanics and anatomy of the dorsal mobile wad, we posit that our patient’s injury occurred when he fell onto his outstretched hand secondary to overwhelming eccentric muscle contracture at time of impact. This injury caused significant upper extremity dysfunction, and surgical intervention was required.

1. Guettler JH, Mayo DB. Avulsion fracture of the origin of the brachioradialis muscle. Am J Orthop. 2001;30(9):693-694.

2. Marchant MH Jr, Gambardella RA, Podesta L. Superficial radial nerve injury after avulsion fracture of the brachioradialis muscle origin in a professional lacrosse player: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):e9-e12.

3. Dawson J, Doll H, Boller I, et al. The development and validation of a patient-reported questionnaire to assess outcomes of elbow surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):466-473.

4. Sathyamoorthy P, Kemp GJ, Rawal A, Rayner V, Frostick SP. Development and validation of an elbow score. Rheumatology. 2004;43(11):1434-1440.

5. Freehafer AA, Peckham PH, Keith MW, Mendelson LS. The brachioradialis: anatomy, properties, and value for tendon transfer in the tetraplegic. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13(1):99-104.

6. Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009.

7. Nakazawa K, Kawakami Y, Fukunaga T, Yano H, Miyashita M. Differences in activation patterns in elbow flexor muscles during isometric, concentric and eccentric contractions. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1993;66(3):214-220.

8. Funk DA, An KN, Morrey BF, Daube JR. Electromyographic analysis of muscles across the elbow joint. J Orthop Res. 1987;5(4):529-538.

The literature includes only 2 case reports of bony avulsion fracture of the origin of the brachioradialis1,2 and, up until now, no case reports of isolated avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis origins from the lateral epicondyle and lateral supracondylar ridge. In this article, we report the case of a 31-year-old man who sustained this injury during a fall onto his outstretched right hand, and we present our surgical repair technique. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 31-year-old right hand–dominant garbage truck worker sustained a right elbow injury and presented 2 months later. He described slipping and falling onto his outstretched right hand while doing his work. He could not describe the exact mechanism or action or position of the arm at time of impact but thought he tried to catch himself on the truck during the fall. At time of injury, he had immediate pain and swelling to the lateral aspect of the right elbow and difficulty when he attempted lifting. He denied antecedent elbow symptoms before the injury. After evaluation by an outside occupational medicine physician, he engaged in treatment consisting of activity modification and physical therapy, including range-of-motion (ROM) exercises and iontophoresis. This course of management failed to completely relieve his symptoms, and he was unable to return to work.

The patient presented to our institution 9 weeks after injury with complaints of pain along the lateral aspect of the elbow, painful flexion-extension, and continued swelling. The pain had been unrelieved with anti-inflammatory medications and opioids. Physical examination revealed tenderness and swelling along the lateral epicondyle and extensor mass of the right elbow. The patient had tenderness, marked weakness, and a palpable soft-tissue defect at the origin of the extensor mass with resisted extension of the wrist (Figure 1). Elbow ROM was from 20° to 120° of flexion, 60° of pronation, and 60° of supination. No varus or valgus instability was present about the elbow. Radiographs did not show any fracture or dislocation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not definitively show extensor tendon avulsion but did identify signal change of the common extensor tendon (Figures 2A, 2B). Advanced imaging was inconclusive, but, given the patient’s history and physical examination findings, he was diagnosed with an avulsion injury of the origin of the extensor mass of the right elbow.

The patient was brought to the operating room, administered general anesthesia, and placed supine on the operating table with a tourniquet on the upper arm. A lateral 4.5-cm incision was made centered over the lateral epicondyle. The origin of the extensor mass was exposed, and isolated avulsions of the extensor carpi radialis longus and the brachioradialis were identified (Figures 3, 4). Underlying the avulsed sleeve of tissue, the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis was found intact. The lateral supracondylar ridge and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus were débrided, and 3 transosseous holes were drilled (using a 2.3-mm bit) through the lateral epicondyle. Four Mason-Allen sutures were placed into the tendon of the common extensor origin using No. 2 braided polyester suture (Ethibond Excel, Ethicon) (Figure 5). The tendon was reduced down to the native footprint, and the sutures were passed through the drill holes and tied down securely (Figure 6). The skin was then closed using layered 4-0 absorbable monofilament suture (Monocryl, Ethicon). The patient was placed in a posterior mold plaster splint with 90° of elbow flexion and with the wrist in 30° of extension.

On postoperative day 3, the patient was seen for a wound check and was placed in a long-arm fiberglass cast (90° of elbow flexion, forearm in neutral, 25° of wrist extension) for immobilization. One week after surgery, he was transitioned to a removable thermoplastic splint, and physical therapy for ROM was initiated. He was allowed therapist-guided active extension of the elbow and flexion of the wrist but was restricted to passive flexion of the elbow and extension of the wrist. Seven weeks after surgery, passive ROM about the elbow was measured, and he was found to have 120° of flexion, 0° extension, 80° pronation, and 80° supination. At 12 weeks, the physical therapy regimen was advanced to include muscle strengthening and active wrist extension and elbow flexion. At 16 weeks, the wrist extensors demonstrated 5/5 strength (Medical Research Council grading system), and the patient was cleared for full activity and weight-bearing without restriction. He returned to work pain-free and without restrictions 18 weeks after surgery. At 2-year follow-up, he had a Mayo performance elbow score of 100 and an Oxford elbow score of 48.3,4 He had full active ROM, full strength, and no subjective pain and was back doing heavy lifting at his job.

Discussion

The brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and extensor carpi radialis brevis originate from the anterolateral aspect of the lateral column of the distal humeral metaphysis and form the dorsal mobile wad. The origin of the brachioradialis is about 7 cm in length and begins about 10 to 11 cm above the elbow.5 The origin and insertions of the mobile wad, specifically the brachioradialis, provide a tremendous mechanical advantage with respect to elbow flexion against resistance, particularly with the forearm in the pronated and semipronated positions.6 With the elbow in 30° of flexion, a force 3 times the body weight can be encountered during strenuous lifting.6,7 We hypothesized these large forces likely led to this injury pattern in the patient we have described.

The literature includes 2 case reports of avulsion fracture of the brachioradialis muscle from its origin on the lateral supracondylar humeral ridge.1,2 To our knowledge, however, there have been no reports of pure avulsion. In our patient’s case, there was no bony fracture, but rather avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis at their origin, with the underlying fibers of the extensor carpi radialis brevis remaining in continuity. Because of the rarity of this injury pattern, there was a significant delay in diagnosis. On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for lateral elbow pain and tenderness included occult fracture, intracapsular plica, osteochondritis dissecans lesion, radial tunnel syndrome, lateral or posterolateral instability, and lateral epicondylitis. Given the absence of antecedent elbow symptoms before the injury, the dynamic soft-tissue asymmetry of the mobile wad with wrist extension, and the palpable soft-tissue defect, we thought the presentation was inconsistent with a simple inflammatory or overuse syndrome, such as lateral epicondylitis. In addition, the physical examination findings were inconsistent with radial tunnel syndrome or disruption of the lateral collateral ligament complex. Elbow MRI did not show an occult fracture, plica, or osteochondritis dissecans lesion but did reveal joint effusion and signal change in the common extensor tendon origin. Interestingly, MRI did not definitively show a tear of the mobile wad. This may be explained by the fact that the fibers of the underlying extensor carpi radialis brevis remained intact. Also potentially involved are the static nature of MRI and potentially suboptimal sequencing and axis of acquisition resulting from the relative infrequency of imaging this joint at certain health care institutions. Our case demonstrates the limitations of MRI in this setting and highlights the need for a detailed history and thorough physical examination for diagnosis.

Funk and colleagues8 used electromyography (EMG) to study the activity of the elbow musculature in uninjured subjects. EMG data were obtained with the elbow joint subjected to resisted flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. During resisted elbow flexion, there was an increasing amount of activity in the extensor carpi radialis with larger angles of elbow flexion. In addition, the brachioradialis demonstrated the most muscle activity of any of the elbow flexors with 90° or more of elbow flexion and forearm pronation, as opposed to other positions in which the brachialis was the primary flexor. For this reason, we hypothesized that our patient’s forearm was pronated and his elbow flexed to 90° or more when he braced for impact. The ensuing injury resulted from a violent eccentric contraction that caused extensive rupture of the lateral elbow musculature from its broad origin. With the forearm in supination or neutral position, we would have expected a possible injury to the distal biceps as opposed to the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis.

In our patient, this injury caused much functional disability, especially with elbow flexion and wrist extension. We hypothesized that, for the muscles to function properly, anatomical restoration would have to be achieved at their known footprint to maintain their mechanical advantage. Therefore, surgical intervention was indicated in our patient, an active laborer. Given the absence of an osseous fracture fragment in this injury pattern, healing must occur at the bone–tendon interface. As tendinous healing is more tenuous and protracted than osseous healing, we preferred transosseous repair. We believed that better tendon-to-bone healing would be possible with drilled osseous tunnels rather than with suture anchors. New studies describing alternative successful methods of treatment would add to our limited body of knowledge regarding this rare injury.

Conclusion

This is the first report of avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis from their origins. Given the biomechanics and anatomy of the dorsal mobile wad, we posit that our patient’s injury occurred when he fell onto his outstretched hand secondary to overwhelming eccentric muscle contracture at time of impact. This injury caused significant upper extremity dysfunction, and surgical intervention was required.

The literature includes only 2 case reports of bony avulsion fracture of the origin of the brachioradialis1,2 and, up until now, no case reports of isolated avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis origins from the lateral epicondyle and lateral supracondylar ridge. In this article, we report the case of a 31-year-old man who sustained this injury during a fall onto his outstretched right hand, and we present our surgical repair technique. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 31-year-old right hand–dominant garbage truck worker sustained a right elbow injury and presented 2 months later. He described slipping and falling onto his outstretched right hand while doing his work. He could not describe the exact mechanism or action or position of the arm at time of impact but thought he tried to catch himself on the truck during the fall. At time of injury, he had immediate pain and swelling to the lateral aspect of the right elbow and difficulty when he attempted lifting. He denied antecedent elbow symptoms before the injury. After evaluation by an outside occupational medicine physician, he engaged in treatment consisting of activity modification and physical therapy, including range-of-motion (ROM) exercises and iontophoresis. This course of management failed to completely relieve his symptoms, and he was unable to return to work.

The patient presented to our institution 9 weeks after injury with complaints of pain along the lateral aspect of the elbow, painful flexion-extension, and continued swelling. The pain had been unrelieved with anti-inflammatory medications and opioids. Physical examination revealed tenderness and swelling along the lateral epicondyle and extensor mass of the right elbow. The patient had tenderness, marked weakness, and a palpable soft-tissue defect at the origin of the extensor mass with resisted extension of the wrist (Figure 1). Elbow ROM was from 20° to 120° of flexion, 60° of pronation, and 60° of supination. No varus or valgus instability was present about the elbow. Radiographs did not show any fracture or dislocation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not definitively show extensor tendon avulsion but did identify signal change of the common extensor tendon (Figures 2A, 2B). Advanced imaging was inconclusive, but, given the patient’s history and physical examination findings, he was diagnosed with an avulsion injury of the origin of the extensor mass of the right elbow.

The patient was brought to the operating room, administered general anesthesia, and placed supine on the operating table with a tourniquet on the upper arm. A lateral 4.5-cm incision was made centered over the lateral epicondyle. The origin of the extensor mass was exposed, and isolated avulsions of the extensor carpi radialis longus and the brachioradialis were identified (Figures 3, 4). Underlying the avulsed sleeve of tissue, the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis was found intact. The lateral supracondylar ridge and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus were débrided, and 3 transosseous holes were drilled (using a 2.3-mm bit) through the lateral epicondyle. Four Mason-Allen sutures were placed into the tendon of the common extensor origin using No. 2 braided polyester suture (Ethibond Excel, Ethicon) (Figure 5). The tendon was reduced down to the native footprint, and the sutures were passed through the drill holes and tied down securely (Figure 6). The skin was then closed using layered 4-0 absorbable monofilament suture (Monocryl, Ethicon). The patient was placed in a posterior mold plaster splint with 90° of elbow flexion and with the wrist in 30° of extension.

On postoperative day 3, the patient was seen for a wound check and was placed in a long-arm fiberglass cast (90° of elbow flexion, forearm in neutral, 25° of wrist extension) for immobilization. One week after surgery, he was transitioned to a removable thermoplastic splint, and physical therapy for ROM was initiated. He was allowed therapist-guided active extension of the elbow and flexion of the wrist but was restricted to passive flexion of the elbow and extension of the wrist. Seven weeks after surgery, passive ROM about the elbow was measured, and he was found to have 120° of flexion, 0° extension, 80° pronation, and 80° supination. At 12 weeks, the physical therapy regimen was advanced to include muscle strengthening and active wrist extension and elbow flexion. At 16 weeks, the wrist extensors demonstrated 5/5 strength (Medical Research Council grading system), and the patient was cleared for full activity and weight-bearing without restriction. He returned to work pain-free and without restrictions 18 weeks after surgery. At 2-year follow-up, he had a Mayo performance elbow score of 100 and an Oxford elbow score of 48.3,4 He had full active ROM, full strength, and no subjective pain and was back doing heavy lifting at his job.

Discussion

The brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and extensor carpi radialis brevis originate from the anterolateral aspect of the lateral column of the distal humeral metaphysis and form the dorsal mobile wad. The origin of the brachioradialis is about 7 cm in length and begins about 10 to 11 cm above the elbow.5 The origin and insertions of the mobile wad, specifically the brachioradialis, provide a tremendous mechanical advantage with respect to elbow flexion against resistance, particularly with the forearm in the pronated and semipronated positions.6 With the elbow in 30° of flexion, a force 3 times the body weight can be encountered during strenuous lifting.6,7 We hypothesized these large forces likely led to this injury pattern in the patient we have described.

The literature includes 2 case reports of avulsion fracture of the brachioradialis muscle from its origin on the lateral supracondylar humeral ridge.1,2 To our knowledge, however, there have been no reports of pure avulsion. In our patient’s case, there was no bony fracture, but rather avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis at their origin, with the underlying fibers of the extensor carpi radialis brevis remaining in continuity. Because of the rarity of this injury pattern, there was a significant delay in diagnosis. On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for lateral elbow pain and tenderness included occult fracture, intracapsular plica, osteochondritis dissecans lesion, radial tunnel syndrome, lateral or posterolateral instability, and lateral epicondylitis. Given the absence of antecedent elbow symptoms before the injury, the dynamic soft-tissue asymmetry of the mobile wad with wrist extension, and the palpable soft-tissue defect, we thought the presentation was inconsistent with a simple inflammatory or overuse syndrome, such as lateral epicondylitis. In addition, the physical examination findings were inconsistent with radial tunnel syndrome or disruption of the lateral collateral ligament complex. Elbow MRI did not show an occult fracture, plica, or osteochondritis dissecans lesion but did reveal joint effusion and signal change in the common extensor tendon origin. Interestingly, MRI did not definitively show a tear of the mobile wad. This may be explained by the fact that the fibers of the underlying extensor carpi radialis brevis remained intact. Also potentially involved are the static nature of MRI and potentially suboptimal sequencing and axis of acquisition resulting from the relative infrequency of imaging this joint at certain health care institutions. Our case demonstrates the limitations of MRI in this setting and highlights the need for a detailed history and thorough physical examination for diagnosis.

Funk and colleagues8 used electromyography (EMG) to study the activity of the elbow musculature in uninjured subjects. EMG data were obtained with the elbow joint subjected to resisted flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction. During resisted elbow flexion, there was an increasing amount of activity in the extensor carpi radialis with larger angles of elbow flexion. In addition, the brachioradialis demonstrated the most muscle activity of any of the elbow flexors with 90° or more of elbow flexion and forearm pronation, as opposed to other positions in which the brachialis was the primary flexor. For this reason, we hypothesized that our patient’s forearm was pronated and his elbow flexed to 90° or more when he braced for impact. The ensuing injury resulted from a violent eccentric contraction that caused extensive rupture of the lateral elbow musculature from its broad origin. With the forearm in supination or neutral position, we would have expected a possible injury to the distal biceps as opposed to the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis.

In our patient, this injury caused much functional disability, especially with elbow flexion and wrist extension. We hypothesized that, for the muscles to function properly, anatomical restoration would have to be achieved at their known footprint to maintain their mechanical advantage. Therefore, surgical intervention was indicated in our patient, an active laborer. Given the absence of an osseous fracture fragment in this injury pattern, healing must occur at the bone–tendon interface. As tendinous healing is more tenuous and protracted than osseous healing, we preferred transosseous repair. We believed that better tendon-to-bone healing would be possible with drilled osseous tunnels rather than with suture anchors. New studies describing alternative successful methods of treatment would add to our limited body of knowledge regarding this rare injury.

Conclusion

This is the first report of avulsion of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis from their origins. Given the biomechanics and anatomy of the dorsal mobile wad, we posit that our patient’s injury occurred when he fell onto his outstretched hand secondary to overwhelming eccentric muscle contracture at time of impact. This injury caused significant upper extremity dysfunction, and surgical intervention was required.

1. Guettler JH, Mayo DB. Avulsion fracture of the origin of the brachioradialis muscle. Am J Orthop. 2001;30(9):693-694.

2. Marchant MH Jr, Gambardella RA, Podesta L. Superficial radial nerve injury after avulsion fracture of the brachioradialis muscle origin in a professional lacrosse player: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):e9-e12.

3. Dawson J, Doll H, Boller I, et al. The development and validation of a patient-reported questionnaire to assess outcomes of elbow surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):466-473.

4. Sathyamoorthy P, Kemp GJ, Rawal A, Rayner V, Frostick SP. Development and validation of an elbow score. Rheumatology. 2004;43(11):1434-1440.

5. Freehafer AA, Peckham PH, Keith MW, Mendelson LS. The brachioradialis: anatomy, properties, and value for tendon transfer in the tetraplegic. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13(1):99-104.

6. Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009.

7. Nakazawa K, Kawakami Y, Fukunaga T, Yano H, Miyashita M. Differences in activation patterns in elbow flexor muscles during isometric, concentric and eccentric contractions. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1993;66(3):214-220.

8. Funk DA, An KN, Morrey BF, Daube JR. Electromyographic analysis of muscles across the elbow joint. J Orthop Res. 1987;5(4):529-538.

1. Guettler JH, Mayo DB. Avulsion fracture of the origin of the brachioradialis muscle. Am J Orthop. 2001;30(9):693-694.

2. Marchant MH Jr, Gambardella RA, Podesta L. Superficial radial nerve injury after avulsion fracture of the brachioradialis muscle origin in a professional lacrosse player: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):e9-e12.

3. Dawson J, Doll H, Boller I, et al. The development and validation of a patient-reported questionnaire to assess outcomes of elbow surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):466-473.

4. Sathyamoorthy P, Kemp GJ, Rawal A, Rayner V, Frostick SP. Development and validation of an elbow score. Rheumatology. 2004;43(11):1434-1440.

5. Freehafer AA, Peckham PH, Keith MW, Mendelson LS. The brachioradialis: anatomy, properties, and value for tendon transfer in the tetraplegic. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13(1):99-104.

6. Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009.

7. Nakazawa K, Kawakami Y, Fukunaga T, Yano H, Miyashita M. Differences in activation patterns in elbow flexor muscles during isometric, concentric and eccentric contractions. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1993;66(3):214-220.

8. Funk DA, An KN, Morrey BF, Daube JR. Electromyographic analysis of muscles across the elbow joint. J Orthop Res. 1987;5(4):529-538.