User login

What has led to the current malpractice crisis? There are 2 main theories.

Physicians, insurers, and hospitals generally blame lawyers and the litigation system for increasing the number of claims filed (claim frequency) and the average payout on claims (claims severity).

Attorneys and consumer groups argue that malpractice insurance goes through natural cycles in costs and charges. For the rise in premiums in the current crisis, they particularly blame decreased investment returns and poor pricing decisions by insurers.

Who’s right?

Research suggests that neither argument alone is persuasive. For instance, a study of the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects results of all malpractice claims payments, found that claims severity did increase since 1991, but not during the current malpractice crisis period when adjusted for inflation: 52% from 1991 to 2003 but only 6% from 2000 to 2003.1 The highest growth rate has been in medium-sized awards, not the large ones you often read about. And, as always, claims severity growth varies among states (FIGURE 1).1

In contrast, when adjusted for population changes, Data Bank studies showed no significant nationwide increase in the number of paid claims from 1991 to 2003. Data from individual states also bear this out.1

Furthermore, studies of the relationship between claims’ payments and premiums have shown only a weakly positive relationship, suggesting other factors are involved. The argument that decreased investment returns have led to large price increases probably has some merit but does not explain the magnitude of the changes or the variation across states.

FIGURE 1

Amount of average paid claim, 1991-2003

So, what’s the answer for physicians?

Most likely, a combination of several changes has led to the recent crisis—increased claims’ costs, poor pricing decisions or cost projections by insurers, and decreased investment income. Rather than seeing these issues as distinct, it may be more useful to see their intrinsic relationships in leading to rapid premium increases and a malpractice crisis.

In this article, the first of 2, I discuss recent events influencing insurance premiums, which may also suggest to you avenues to explore in optimizing your own coverage. In part 2, I will address our current tort system and concrete proposals for change being pursued.

How premiums are determined

Almost all physicians carry professional liability (malpractice) insurance, either by choice or legal requirement. Coverage is usually purchased individually or by group from a commercial company or a physician-owned mutual company. Hospitals may purchase insurance or be self-insured, and their physician employees may be covered through those policies.

In theory, a tort system to resolve malpractice claims is supposed to serve as a negative incentive to physicians to practice high quality medicine. But the 1999 Institute of Medicine report on the occurrence and ramifications of medical errors, To Err is Human,2 provided evidence that the malpractice system has failed to accomplish this goal.

Unlike auto insurance, malpractice premiums are mainly determined by the class of physician (including type of work) and geography, rather than by an individual’s practice experience. Auto insurance premiums are adjusted according to the insured’s driving record. This is difficult to accomplish with malpractice insurance because claims experience is too variable over short periods of time.

Insurers take the following into account when they set premiums: 1) anticipated payouts to a class of physicians and the uncertainty of their estimate; 2) expected administrative expenses to manage the insurance; 3) future investment income; and 4) desired amount of profit. Information on past losses and expenses is used but, clearly, much of the determination involves complicated predictions.

Another characteristic that makes rate setting difficult is the length of time from the occurrence of an event to the filing of a claim to the resolution of that claim. On average, this is 4 to 5 years. The difficulty in predicting the liability for claims that have not yet been filed adds to the problem in setting premiums accurately.

How does your state manage rate setting?

Although malpractice has been a political issue at the federal level in the past few years, the reality is that, like most insurance, it is mainly regulated by the states.

States with substantial restrictions (17 states in 2004) require insurers to file rate changes and gain approval before prices can change.

States with less restrictive environments require such prior approval only if rate increases exceed a certain amount (23 in 2004) or only require notification after rates are changed (9 in 2004).1

Whether these varying types of state regulation lead to higher or lower premiums is unclear.

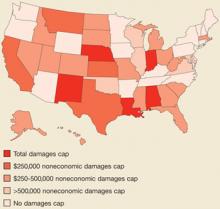

In addition to these strategies, states have also implemented an array of tort reforms in an attempt to address the cost of physician malpractice policies. Caps have been the most popular reform, with 26 states instituting them (FIGURE 2).3

FIGURE 2

Caps on damages by state

Recent events influencing premiums

A number of changes in the past few years have occurred in the malpractice arena

- Increased numbers of physician-owned companies and fewer commercial carriers since the malpractice crisis of the 1970s. These companies often give physicians better rates and more control, but some have been undercapitalized and not survived.

- A rise in the cost of reinsurance since September 11. Reinsurance covers costs above a certain level and limits companies’ losses in a given year. Reinsurers suffered large losses from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and, subsequently, raised their prices significantly to all liability companies.

- More hospitals self-insuring to better control rates and their risk pool leading increasing numbers of physicians to obtain their malpractice coverage through hospitals. This lowers their costs in comparison to those who practice in small groups or solo settings.

- A shift in the type of insurance from occurrence (all incidents in the policy year are covered regardless of when the claim is filed) to claims-made policies (coverage is for claims filed in the policy year regardless of when the event occurred). With claims-made insurance, physicians have to purchase costly “tail” policies to cover the possibility of incidents during the years of coverage becoming future claims.

- The growth of state-mandated funds as insurers of last resort for physicians who cannot find any coverage. These funds are financed by surcharges on hospital and physician malpractice policies, which in turn increases those costs.

- A decrease in companies’ investment yields since 2000 (from 5.2% in 2000 to4.3% in 2002), in spite of the fact that insurers’ portfolios are quite conservative as required by state law. While some companies saw their investment income drop by 50% in these years, this amount is still only a small part of insurers’ total income.

Options to explore

- Check with your state’s division of insurance website to see if there is a list of carriers, and information about their experience.

- Rather than a claims-made policy, consider getting an occurrence policy that will eliminate the worry and cost of purchasing “tail” insurance. If you work for a group practice, inquire about whether occurrence insurance is an option. If occurrence insurance is not available or seems too costly, ask your agent about what a typical tail policy would cost.

- You may want to inquire about purchasing insurance through a local hospital, which could yield cost savings.

- Don’t skimp on coverage amounts. Consider getting risk-management training to learn what you can do to minimize the risk of being sued.

A malpractice crisis, according to the AMA, occurs when “patients lose access to care as a result of a broken medical liability system… that causes physicians’ insurance premiums to skyrocket forcing them to restrict their practice.” An alternate description would be when insurers’ financial situation deteriorates resulting in higher than average increases in premiums or decrease in the supply of insurance. The existence and severity of a crisis varies from state to state (see map at right).4

Insurance becomes relatively unaffordable when premiums increase rapidly, as occurred in the second malpractice crisis in the mid-1980s and also in the current crisis, which has seen increasing premiums since 1999 and some moderation since 2004. Increases in premiums may differ across states, within states, and among specialties.

How providers feel about premium increases depends on both the size and rapidity of the increases and by their ability to collect more for their services to pay for increases. In the current crisis, providers have had more difficulty maintaining a balance between cost increases and income as discounted fee contracts and lack of growth in Medicare and Medicaid payments have constrained growth in practice revenue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Chandra A, Nundy S, Seabury SA. The growth of physician medical malpractice payments: evidence from the National Practitioner Data Bank. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jan-Jun; Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-240-W5-249. Available at: content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.w5.240. Accessed on July 18, 2006.

2. Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

3. Mello MM. Medical malpractice: Impact of crisis and effect of state tort reforms. The Synthesis Project Policy Brief #10, May 2006. Available at: www.rwjf.org/publications/synthesis/reports_and_briefs/charts/no10_pb_fig2.jpg. Accessed on July 18, 2006.

4. Medical liability crisis map. AMA News and Information [website]. Available at: www.amaassn.org/ama/noindex/category/11871.html. Accessed on July 18. 2006.

What has led to the current malpractice crisis? There are 2 main theories.

Physicians, insurers, and hospitals generally blame lawyers and the litigation system for increasing the number of claims filed (claim frequency) and the average payout on claims (claims severity).

Attorneys and consumer groups argue that malpractice insurance goes through natural cycles in costs and charges. For the rise in premiums in the current crisis, they particularly blame decreased investment returns and poor pricing decisions by insurers.

Who’s right?

Research suggests that neither argument alone is persuasive. For instance, a study of the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects results of all malpractice claims payments, found that claims severity did increase since 1991, but not during the current malpractice crisis period when adjusted for inflation: 52% from 1991 to 2003 but only 6% from 2000 to 2003.1 The highest growth rate has been in medium-sized awards, not the large ones you often read about. And, as always, claims severity growth varies among states (FIGURE 1).1

In contrast, when adjusted for population changes, Data Bank studies showed no significant nationwide increase in the number of paid claims from 1991 to 2003. Data from individual states also bear this out.1

Furthermore, studies of the relationship between claims’ payments and premiums have shown only a weakly positive relationship, suggesting other factors are involved. The argument that decreased investment returns have led to large price increases probably has some merit but does not explain the magnitude of the changes or the variation across states.

FIGURE 1

Amount of average paid claim, 1991-2003

So, what’s the answer for physicians?

Most likely, a combination of several changes has led to the recent crisis—increased claims’ costs, poor pricing decisions or cost projections by insurers, and decreased investment income. Rather than seeing these issues as distinct, it may be more useful to see their intrinsic relationships in leading to rapid premium increases and a malpractice crisis.

In this article, the first of 2, I discuss recent events influencing insurance premiums, which may also suggest to you avenues to explore in optimizing your own coverage. In part 2, I will address our current tort system and concrete proposals for change being pursued.

How premiums are determined

Almost all physicians carry professional liability (malpractice) insurance, either by choice or legal requirement. Coverage is usually purchased individually or by group from a commercial company or a physician-owned mutual company. Hospitals may purchase insurance or be self-insured, and their physician employees may be covered through those policies.

In theory, a tort system to resolve malpractice claims is supposed to serve as a negative incentive to physicians to practice high quality medicine. But the 1999 Institute of Medicine report on the occurrence and ramifications of medical errors, To Err is Human,2 provided evidence that the malpractice system has failed to accomplish this goal.

Unlike auto insurance, malpractice premiums are mainly determined by the class of physician (including type of work) and geography, rather than by an individual’s practice experience. Auto insurance premiums are adjusted according to the insured’s driving record. This is difficult to accomplish with malpractice insurance because claims experience is too variable over short periods of time.

Insurers take the following into account when they set premiums: 1) anticipated payouts to a class of physicians and the uncertainty of their estimate; 2) expected administrative expenses to manage the insurance; 3) future investment income; and 4) desired amount of profit. Information on past losses and expenses is used but, clearly, much of the determination involves complicated predictions.

Another characteristic that makes rate setting difficult is the length of time from the occurrence of an event to the filing of a claim to the resolution of that claim. On average, this is 4 to 5 years. The difficulty in predicting the liability for claims that have not yet been filed adds to the problem in setting premiums accurately.

How does your state manage rate setting?

Although malpractice has been a political issue at the federal level in the past few years, the reality is that, like most insurance, it is mainly regulated by the states.

States with substantial restrictions (17 states in 2004) require insurers to file rate changes and gain approval before prices can change.

States with less restrictive environments require such prior approval only if rate increases exceed a certain amount (23 in 2004) or only require notification after rates are changed (9 in 2004).1

Whether these varying types of state regulation lead to higher or lower premiums is unclear.

In addition to these strategies, states have also implemented an array of tort reforms in an attempt to address the cost of physician malpractice policies. Caps have been the most popular reform, with 26 states instituting them (FIGURE 2).3

FIGURE 2

Caps on damages by state

Recent events influencing premiums

A number of changes in the past few years have occurred in the malpractice arena

- Increased numbers of physician-owned companies and fewer commercial carriers since the malpractice crisis of the 1970s. These companies often give physicians better rates and more control, but some have been undercapitalized and not survived.

- A rise in the cost of reinsurance since September 11. Reinsurance covers costs above a certain level and limits companies’ losses in a given year. Reinsurers suffered large losses from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and, subsequently, raised their prices significantly to all liability companies.

- More hospitals self-insuring to better control rates and their risk pool leading increasing numbers of physicians to obtain their malpractice coverage through hospitals. This lowers their costs in comparison to those who practice in small groups or solo settings.

- A shift in the type of insurance from occurrence (all incidents in the policy year are covered regardless of when the claim is filed) to claims-made policies (coverage is for claims filed in the policy year regardless of when the event occurred). With claims-made insurance, physicians have to purchase costly “tail” policies to cover the possibility of incidents during the years of coverage becoming future claims.

- The growth of state-mandated funds as insurers of last resort for physicians who cannot find any coverage. These funds are financed by surcharges on hospital and physician malpractice policies, which in turn increases those costs.

- A decrease in companies’ investment yields since 2000 (from 5.2% in 2000 to4.3% in 2002), in spite of the fact that insurers’ portfolios are quite conservative as required by state law. While some companies saw their investment income drop by 50% in these years, this amount is still only a small part of insurers’ total income.

Options to explore

- Check with your state’s division of insurance website to see if there is a list of carriers, and information about their experience.

- Rather than a claims-made policy, consider getting an occurrence policy that will eliminate the worry and cost of purchasing “tail” insurance. If you work for a group practice, inquire about whether occurrence insurance is an option. If occurrence insurance is not available or seems too costly, ask your agent about what a typical tail policy would cost.

- You may want to inquire about purchasing insurance through a local hospital, which could yield cost savings.

- Don’t skimp on coverage amounts. Consider getting risk-management training to learn what you can do to minimize the risk of being sued.

A malpractice crisis, according to the AMA, occurs when “patients lose access to care as a result of a broken medical liability system… that causes physicians’ insurance premiums to skyrocket forcing them to restrict their practice.” An alternate description would be when insurers’ financial situation deteriorates resulting in higher than average increases in premiums or decrease in the supply of insurance. The existence and severity of a crisis varies from state to state (see map at right).4

Insurance becomes relatively unaffordable when premiums increase rapidly, as occurred in the second malpractice crisis in the mid-1980s and also in the current crisis, which has seen increasing premiums since 1999 and some moderation since 2004. Increases in premiums may differ across states, within states, and among specialties.

How providers feel about premium increases depends on both the size and rapidity of the increases and by their ability to collect more for their services to pay for increases. In the current crisis, providers have had more difficulty maintaining a balance between cost increases and income as discounted fee contracts and lack of growth in Medicare and Medicaid payments have constrained growth in practice revenue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

What has led to the current malpractice crisis? There are 2 main theories.

Physicians, insurers, and hospitals generally blame lawyers and the litigation system for increasing the number of claims filed (claim frequency) and the average payout on claims (claims severity).

Attorneys and consumer groups argue that malpractice insurance goes through natural cycles in costs and charges. For the rise in premiums in the current crisis, they particularly blame decreased investment returns and poor pricing decisions by insurers.

Who’s right?

Research suggests that neither argument alone is persuasive. For instance, a study of the National Practitioner Data Bank, which collects results of all malpractice claims payments, found that claims severity did increase since 1991, but not during the current malpractice crisis period when adjusted for inflation: 52% from 1991 to 2003 but only 6% from 2000 to 2003.1 The highest growth rate has been in medium-sized awards, not the large ones you often read about. And, as always, claims severity growth varies among states (FIGURE 1).1

In contrast, when adjusted for population changes, Data Bank studies showed no significant nationwide increase in the number of paid claims from 1991 to 2003. Data from individual states also bear this out.1

Furthermore, studies of the relationship between claims’ payments and premiums have shown only a weakly positive relationship, suggesting other factors are involved. The argument that decreased investment returns have led to large price increases probably has some merit but does not explain the magnitude of the changes or the variation across states.

FIGURE 1

Amount of average paid claim, 1991-2003

So, what’s the answer for physicians?

Most likely, a combination of several changes has led to the recent crisis—increased claims’ costs, poor pricing decisions or cost projections by insurers, and decreased investment income. Rather than seeing these issues as distinct, it may be more useful to see their intrinsic relationships in leading to rapid premium increases and a malpractice crisis.

In this article, the first of 2, I discuss recent events influencing insurance premiums, which may also suggest to you avenues to explore in optimizing your own coverage. In part 2, I will address our current tort system and concrete proposals for change being pursued.

How premiums are determined

Almost all physicians carry professional liability (malpractice) insurance, either by choice or legal requirement. Coverage is usually purchased individually or by group from a commercial company or a physician-owned mutual company. Hospitals may purchase insurance or be self-insured, and their physician employees may be covered through those policies.

In theory, a tort system to resolve malpractice claims is supposed to serve as a negative incentive to physicians to practice high quality medicine. But the 1999 Institute of Medicine report on the occurrence and ramifications of medical errors, To Err is Human,2 provided evidence that the malpractice system has failed to accomplish this goal.

Unlike auto insurance, malpractice premiums are mainly determined by the class of physician (including type of work) and geography, rather than by an individual’s practice experience. Auto insurance premiums are adjusted according to the insured’s driving record. This is difficult to accomplish with malpractice insurance because claims experience is too variable over short periods of time.

Insurers take the following into account when they set premiums: 1) anticipated payouts to a class of physicians and the uncertainty of their estimate; 2) expected administrative expenses to manage the insurance; 3) future investment income; and 4) desired amount of profit. Information on past losses and expenses is used but, clearly, much of the determination involves complicated predictions.

Another characteristic that makes rate setting difficult is the length of time from the occurrence of an event to the filing of a claim to the resolution of that claim. On average, this is 4 to 5 years. The difficulty in predicting the liability for claims that have not yet been filed adds to the problem in setting premiums accurately.

How does your state manage rate setting?

Although malpractice has been a political issue at the federal level in the past few years, the reality is that, like most insurance, it is mainly regulated by the states.

States with substantial restrictions (17 states in 2004) require insurers to file rate changes and gain approval before prices can change.

States with less restrictive environments require such prior approval only if rate increases exceed a certain amount (23 in 2004) or only require notification after rates are changed (9 in 2004).1

Whether these varying types of state regulation lead to higher or lower premiums is unclear.

In addition to these strategies, states have also implemented an array of tort reforms in an attempt to address the cost of physician malpractice policies. Caps have been the most popular reform, with 26 states instituting them (FIGURE 2).3

FIGURE 2

Caps on damages by state

Recent events influencing premiums

A number of changes in the past few years have occurred in the malpractice arena

- Increased numbers of physician-owned companies and fewer commercial carriers since the malpractice crisis of the 1970s. These companies often give physicians better rates and more control, but some have been undercapitalized and not survived.

- A rise in the cost of reinsurance since September 11. Reinsurance covers costs above a certain level and limits companies’ losses in a given year. Reinsurers suffered large losses from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and, subsequently, raised their prices significantly to all liability companies.

- More hospitals self-insuring to better control rates and their risk pool leading increasing numbers of physicians to obtain their malpractice coverage through hospitals. This lowers their costs in comparison to those who practice in small groups or solo settings.

- A shift in the type of insurance from occurrence (all incidents in the policy year are covered regardless of when the claim is filed) to claims-made policies (coverage is for claims filed in the policy year regardless of when the event occurred). With claims-made insurance, physicians have to purchase costly “tail” policies to cover the possibility of incidents during the years of coverage becoming future claims.

- The growth of state-mandated funds as insurers of last resort for physicians who cannot find any coverage. These funds are financed by surcharges on hospital and physician malpractice policies, which in turn increases those costs.

- A decrease in companies’ investment yields since 2000 (from 5.2% in 2000 to4.3% in 2002), in spite of the fact that insurers’ portfolios are quite conservative as required by state law. While some companies saw their investment income drop by 50% in these years, this amount is still only a small part of insurers’ total income.

Options to explore

- Check with your state’s division of insurance website to see if there is a list of carriers, and information about their experience.

- Rather than a claims-made policy, consider getting an occurrence policy that will eliminate the worry and cost of purchasing “tail” insurance. If you work for a group practice, inquire about whether occurrence insurance is an option. If occurrence insurance is not available or seems too costly, ask your agent about what a typical tail policy would cost.

- You may want to inquire about purchasing insurance through a local hospital, which could yield cost savings.

- Don’t skimp on coverage amounts. Consider getting risk-management training to learn what you can do to minimize the risk of being sued.

A malpractice crisis, according to the AMA, occurs when “patients lose access to care as a result of a broken medical liability system… that causes physicians’ insurance premiums to skyrocket forcing them to restrict their practice.” An alternate description would be when insurers’ financial situation deteriorates resulting in higher than average increases in premiums or decrease in the supply of insurance. The existence and severity of a crisis varies from state to state (see map at right).4

Insurance becomes relatively unaffordable when premiums increase rapidly, as occurred in the second malpractice crisis in the mid-1980s and also in the current crisis, which has seen increasing premiums since 1999 and some moderation since 2004. Increases in premiums may differ across states, within states, and among specialties.

How providers feel about premium increases depends on both the size and rapidity of the increases and by their ability to collect more for their services to pay for increases. In the current crisis, providers have had more difficulty maintaining a balance between cost increases and income as discounted fee contracts and lack of growth in Medicare and Medicaid payments have constrained growth in practice revenue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Chandra A, Nundy S, Seabury SA. The growth of physician medical malpractice payments: evidence from the National Practitioner Data Bank. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jan-Jun; Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-240-W5-249. Available at: content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.w5.240. Accessed on July 18, 2006.

2. Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

3. Mello MM. Medical malpractice: Impact of crisis and effect of state tort reforms. The Synthesis Project Policy Brief #10, May 2006. Available at: www.rwjf.org/publications/synthesis/reports_and_briefs/charts/no10_pb_fig2.jpg. Accessed on July 18, 2006.

4. Medical liability crisis map. AMA News and Information [website]. Available at: www.amaassn.org/ama/noindex/category/11871.html. Accessed on July 18. 2006.

1. Chandra A, Nundy S, Seabury SA. The growth of physician medical malpractice payments: evidence from the National Practitioner Data Bank. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jan-Jun; Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-240-W5-249. Available at: content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.w5.240. Accessed on July 18, 2006.

2. Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

3. Mello MM. Medical malpractice: Impact of crisis and effect of state tort reforms. The Synthesis Project Policy Brief #10, May 2006. Available at: www.rwjf.org/publications/synthesis/reports_and_briefs/charts/no10_pb_fig2.jpg. Accessed on July 18, 2006.

4. Medical liability crisis map. AMA News and Information [website]. Available at: www.amaassn.org/ama/noindex/category/11871.html. Accessed on July 18. 2006.