User login

The less time that passes between the onset of psychosis and initiation of appropriate treatment, the greater the patient’s odds of recovery.1 However, relapse prevention is a major clinical challenge because >80% of patients will relapse within 5 years, and, on average, 40% to 50% of patients with a first-episode schizophrenia will relapse within 2 years depending on the definition used and patient characteristics.2 Although there are several explanations and contributing factors to relapses, nonadherence—partial or complete discontinuation of antipsychotics—is a primary risk factor, contributing to a 5-fold increase in relapse risk.3

As such, optimal antipsychotic selection, dosing, and monitoring play an important role in managing this illness. Patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) are unusual in some ways, compared with patients with multiple episodes of psychosis and represent a different stage of schizophrenia.

In this 2-part series, we will discuss pharmacotherapy for FEP. This article focuses on antipsychotic selection, dosage, and duration of treatment among these patients. The second article, in the July 2015 issue, reviews the rationale and evidence for non-standard, first-line therapies, including long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine.

Defining FEP

FEP refers to a patient who has presented, been evaluated, and received treatment for the first psychotic episode associated with a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis.4 FEP is part of a trajectory marked by tran sitional periods. The patient transitions from being “healthy” to a prodromal state characterized by: (1) nonpsychotic behavioral disturbances such as depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder, (2) attenuated psychotic symptoms not requiring treatment, then converting to (3) psychotic symptoms prompting initial presentation for antipsychotic pharmacotherapy, leading to (4) a formal diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder and, subsequently, schizophrenia, requiring treatment to stabilize symptoms.

There are 2 critical periods along this continuum: prodromal stage and the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP). The prodromal period is a retrospectively identified time where the patient shows initial nonpsychotic disturbances (eg, cognitive and behavioral symptoms) before exhibiting clinical diagnostic criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Approximately one-third of patients exhibiting these symptoms convert to psychosis within 1 year, and early treatment engagement at this stage has been shown to improve outcomes.5 The DUP is the time from when a patient has noticeable psychotic symptoms to initiation of drug treatment. The DUP is a consistent predictor of clinical outcome in schizophrenia, including negative symptoms, quality of life, and functional capacity.1

Antipsychotic selection

Treatment goals for FEP patients include:

• minimizing the DUP

• rapidly stabilizing psychosis

• achieving full symptomatic remission

• preventing relapse.

Several treatment guidelines for managing schizophrenia offer variable recommendations for initial antipsychotic treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia (Table 1).6-15 Most recommend second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) over first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs)6,8,9,13,15 with specific recommendations on minimizing neurologic and metabolic adverse effects—to which FEP patients are susceptible—by avoiding high-potency and neurotoxic FGAs (eg, haloperidol and fluphenazine),7 clozapine,11,14 olanzapine,11 or ziprasidone.14 Two guidelines—the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network—do not state a preference for antipsychotic selection.10,12

The rationale for these recommendations is based on efficacy data, tolerability differences, FDA-approved indications, and recent FDA approvals with sparse post-marketing data. Of note, there are a lack of robust data for newer antipsychotics (eg, aripiprazole, paliperidone, iloperidone, asenapine, and lurasidone) in effectively and safely treating FEP; however, given the results of other antipsychotics studies, it is likely the efficacy and tolerability of these drugs can be extrapolated from experience with multi-episode patients.

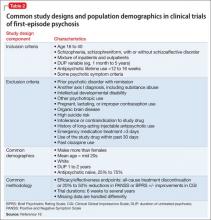

Study design and demographics. Research studies of FEP share some similarities in study design; however, there is enough variability to make it difficult to compare studies and generalize findings (Table 2).16 The variability of DUP is a limitation when comparing studies because it is a significant predictor of clinical outcome. Patients who abuse substances—and often are more challenging to treat17—typically are excluded from these trials, which could explain the high response rate documented in studies of first-episode schizophrenia.

In addition, some FEP patients included in clinical trials might not be truly antipsychotic naïve; an estimated 25% to 75% of patients in these studies are antipsychotic naïve. This is an important consideration when comparing data on adverse effects that occur early in treatment. Additionally, acknowledging the advantages and disadvantages of how to handle missing data is critical because of the high dropout rate observed in these studies.18

Efficacy. There is a high response rate to antipsychotic therapy—ranging from 46% to 96%, depending on the study—in patients with first-episode schizophrenia.3 The response mainly is seen in reduction of positive symptoms because typically negative and cognitive symptoms do not respond to antipsychotics. One study reported only 29% of patients achieved both positive and negative symptom remission.19 It is likely that secondary negative symptoms caused by social withdrawal, reduced speech, and avoidance improve when positive symptoms subside, but primary negative symptoms endure.In general, there is a lack of evidence suggesting that 1 antipsychotic class or agent is more effective than another. Studies mainly assess effectiveness using the primary outcome measure of all-cause discontinuation, such as the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study.20 This outcome measure is a mixture of patient preference, tolerability, and efficacy that provides a more generalizable gauge on how well the treatment works in the clinic rather than tightly regulated settings such as clinical trials. A recent meta-analysis supports no differences in efficacy among antipsychotics in early-episode psychosis.21

Tolerability. Because there are no significant differences among antipsychotic classes or agents in terms of efficacy in first-episode schizophrenia, drug selection is guided mainly by (1) the adverse effect profile and (2) what should be avoided depending on patient-specific variables. Evidence suggests first-episode patients are more sensitive to adverse effects of antipsychotics, particularly neurologic side effects (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a table comparing adverse effects of antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis).18,22-29 Overall adverse effect profiles remain similar across FEP or multi-episode patients, but tend to be more exaggerated in drug-naïve patients with FEP.

Regarding FGA side effects, McEvoy et al18 demonstrated the neuroleptic threshold occurs at 50% lower haloperidol dosages in patients with first-episode schizophrenia (2.1 mg/d) compared with multi-episode schizophrenia (4.3 mg/d). Other trials suggest SGAs are associated with a lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) or use of adjunctive therapies such as anticholinergic drugs or benzodiazepines.23-27 An exception to this statement is that higher risperidone dosages (≥4 to 6 mg/d) have been found to have higher rates of EPS and use of adjunctive medications to treat these symptoms in FEP.26 This is important because studies report higher discontinuation rates with more severe adverse effects of antipsychotics.

Cardiometabolic effects are of particular concern in first-episode patients because most weight gain happens in the first 3 to 4 months of treatment and remains throughout the first year.18,24,29,30 Studies have shown that olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone are associated with more clinically significant weight gain compared with haloperidol and ziprasidone.23-25 Olanzapine-associated weight gain has been reported to be twice that of quetiapine and risperidone.18 Regardless, the EUFEST trial did not find a difference in clinically significant weight gain after 12 months among the antipsychotics studied, including haloperidol and ziprasidone.25

Weight gain associated with these antipsychotics is accompanied by changes in fasting triglycerides, glucose, total cholesterol,23 and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol as well as an increase in body mass index (BMI) categorization29 (eg, shift from normal to overweight).18,25 Patients with lower baseline BMI and in racial minority groups might experience more rapid weight gain regardless of antipsychotic selection.29,30

Hyperprolactinemia could be under-recognized and could contribute to early treatment discontinuation.31 Evidence in patients with first-episode schizophrenia suggests similar outcomes as those seen in multi-episode patients, in whom risperidone is associated with higher prolactin elevations and clinically significant hyperprolactinemia (eg, galactorrhea and gynecomastia) compared with olanzapine, quetiapine, and low-dose haloperidol.18,23,24 However, there is a lack of studies that assess whether long-term therapy with strong D2 receptor antagonists increases the risk of bone demineralization or pathological fractures when started before patients’ bones reach maximum density in their mid-20s.31

Antipsychotic dosing

Given the high rate of treatment response in FEP and patients’ higher sensitivity to antipsychotic adverse effects, particularly EPS, guidelines recommend antipsychotic dosages lower than those used for multi-episode schizophrenia,11 especially FGAs. Based on trial data, commonly used dosages include:

• haloperidol, ≤5 mg/d23-25,29

• olanzapine, 10 mg/d18,23,25,29

• risperidone, ≤4 to 6 mg/d.18,24,29,32

In general, haloperidol and risperidone, 2 to 3 mg/d, were well tolerated and effective in trials. Higher quetiapine dosages of 500 to 600 mg/d could be required.11,18,25

According to a survey on prescribing practices of antipsychotic selection and dosing in first-episode schizophrenia,4 clinical prescribing practices tend to use unnecessarily high initial antipsychotic dosing compared with trial data. There also is variability in the usual target antipsychotic dosage ranging from 50% lower dosages to normal dosages in chronic schizophrenia to above FDA-approved maximum dosages for olanzapine (which may be necessary to counteract tobacco-induced cytochrome P450 1A2 enzyme induction).

In addition, these clinicians reported prescribing aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with weaker evidence (eg, case reports, case series, open-label studies) supporting its efficacy and tolerability in FEP. These prescribing practices could reflect attempts to reduce the DUP and achieve symptom remission, so long as tolerability is not a concern.

Essentially, prescribed dosages should be based on symptom improvement and tolerability. This ideal dosage will vary as illustrated by Kapur et al,33 who reported that FEP patients (N = 20) given haloperidol, 1 mg or 2.5 mg/d, had D2 receptor occupancy rates of 38% to 87%, which was significantly dose-related (1 mg/d mean = 59%, 2.5 mg/d mean = 75%). Clinical response and EPS significantly increased as D2 receptor occupancy exceeded 65% and 78%, respectively.

Antipsychotic response

When should you expect to see symptom improvement in patients with first-episode schizophrenia?

Emsley et al34 reported a 77.6% response rate among first-episode patients (N = 522) treated with low dosages of risperidone (mean modal dosage [MMD] = 3.3 mg/d) and haloperidol (MMD = 2.9 mg/d). They found variable response times that were evenly dispersed over a 10-week period. Nearly one-quarter (22.5%) did not respond until after week 4 and 11.2% did not respond until after week 8. In a study of FEP patients (N = 112) treated with olanzapine (MMD = 11.8 mg/d) or risperidone (MMD = 3.9 mg/d), Gallego et al35 reported a cumulative response of 39.6% at week 8 and 65.1% at week 16.

Although there is evidence that, among multi-episode patients, early nonresponse to antipsychotic therapy could predict subsequent nonresponse,36 the evidence is mixed for first-episode schizophrenia. Studies by Emsley et al34 and Gallego et al35 did not find that early nonresponse at weeks 1 or 2 predicted subsequent nonresponse at week 4 or later. However, other studies support the idea that early nonresponse predicts subsequent nonresponse and early antipsychotic response predicts future response in first-episode patients, with good specificity and sensitivity.37,38

Overall, treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia is variable. An adequate antipsychotic trial may be longer, 8 to 16 weeks, compared with 4 to 8 weeks in multi-episode patients. Because research suggests that failure to respond to treatment may lead to medication nonadherence,39 it is reasonable to consider switching antipsychotics when a patient experiences minimal or no response to antipsychotic therapy at week 2; however, this should be a patient-specific decision.

How long should you continue therapy after symptom remission?

There is a lack of consensus on the duration of therapy for a patient treated for first-episode schizophrenia because a small percentage (10% to 20%) do not relapse after the first psychotic episode.3 In general, treatment guidelines and expert consensus statements recommend at least 1 to 2 years of treatment before considering a discontinuation trial.7,10-11 Discuss the benefits and risks of maintenance treatment with your patient and obtain informed consent. With patients with minimal insight, obtaining proper consent is not possible and the physician must exercise judgment unilaterally, if necessary, after educating the family.

After at least 12 months of treatment, antipsychotic therapy could continue indefinitely, depending on patient-specific factors. There are no predictors for identifying patients who do not require maintenance therapy beyond the first psychotic episode. The absence of negative and cognitive deficits could provide clues that a patient might be a candidate for antipsychotic tapering.

Predicting the treatment course

Research investigating clinical predictors or biomarkers that forecast whether a patient will respond to treatment is preliminary. Many characteristics have been identified (Table 31,3,4,23,25,40) and include shorter DUP,1 poorer premorbid function,3 antipsychotic discontinuation,3 a trusting patient-doctor relationship,41 and antipsychotic-related adverse effects,23,25 which are predictive of response, nonresponse, relapse, adherence, and nonadherence, respectively.

Bottom Line

The goals of pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia are to minimize the duration of untreated psychosis and target full remission of positive symptoms using the lowest possible antipsychotic dosages. Pharmacotherapy should continued for 1 to 2 years, with longer duration considered if it is discussed with the patient and with vigilant monitoring for adverse effects and suboptimal medication nonadherence to prevent relapse.

Editor’s note: The second article in this series in the July 2015 issue reviews the rationale and evidence for non-standard, first-line therapies, including long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine.

Related Resources

• Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project Early Treatment Program. National Institute of Mental Health. http://raiseetp.org.

• Martens L, Baker S. Promoting recovery from first episode psychosis: a guide for families. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/ Documents/www.camh.net/AboutCAMH/Guideto CAMH/MentalHealthPrograms/SchizophreniaProgram/ 3936PromotingRecoveryFirstEpisodePsychosisfinal.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Lurasidone • Latuda

Asenapine • Saphris Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Clozapine • Clozaril Paliperidone • Invega

Fluphenazine • Prolixin Quetiapine • Seroquel

Iloperidone • Fanapt Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Gardner reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Nasrallah is a consultant to Acadia, Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Sunovion, and is a speaker for Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, and Sunovion.

1. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

2. Bradford DW, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. Pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia and related nonaffective psychoses. Drugs. 2003;63(21):2265-2283.

3. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following a response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

4. Weiden PJ, Buckley PF, Grody M. Understanding and treating “first-episode” schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(3):481-510.

5. Madaan V, Bestha DP, Kolli V. Schizophrenia prodrome: an optimal approach. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):16-20, 29-30.

6. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

7. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620.

8. Canadian Psychiatric Association. Clinical practice guideline. Treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(13 suppl 1):7S-57S.

9. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A. Treatment of schizophrenia 1999. Expert consensus guideline series. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 11):4-80.

10. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical guideline 178: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. London, United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2014.

11. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71-93.

12. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of schizophrenia. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2013. SIGN publication no. 131.

13. Argo TR, Crismon ML, Miller AL, et al. Texas Medication Algorithm Project procedural manual. Schizophrenia treatment algorithms. Austin, Texas: Texas Department of State Health Services; 2008.

14. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller Al, et al. The Mount Sinai conference on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):5-16.

15. Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9(4):248-312.

16. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psych. 1999;56(3):241-247.

17. Green AI, Tohen MF, Hamer RM, et al. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophr Res. 2004;66(2-3):125-135.

18. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7): 1050-1060.

19. Henry LP, Amminger GP, Harris MG, et al. The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):716-728.

20. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New Engl J Med. 2005; 353(12):1209-1223.

21. Crossley NA, Constante M, McGuire P, et al. Efficacy of atypical v. typical antipsychotics in the treatment of early psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):434-439.

22. McEvoy JP, Hogarty GE, Steingard S. Optimal dose of neuroleptic in acute schizophrenia: a controlled study of the neuroleptic threshold and higher haloperidol dose. Arch Gen Psych. 1991;48(8):739-745.

23. Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, et al; HGDH Study Group. Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1396-1404.

24. Schooler N, Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, et al; Early Psychosis Global Working Group. Risperidone and haloperidol in first-episode psychosis: a long-term randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):947-953.

25. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

26. Emsley RA; Risperidone Working Group. Risperidone in the treatment of first-episode psychotic patients: a double-blind multicenter study. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(4):721-729.

27. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naïve first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):995-1003.

28. Girgis RR, Phillips MR, Li X, et al. Clozapine v. chlorpromazine in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: 9-year outcomes of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):281-288.

29. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Napolitano B, et al. Randomized comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone for the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia: 4-month outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2096-2102.

30. Zipursky RB, Gu H, Green AI, et al. Course and predictors of weight gain in people with first-episode psychosis treated with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:537-543.

31. Taylor M, Waight A, Leonard B. Advances in the understanding and challenges facing the management of first-episode schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2012; 26(suppl 5):3-5.

32. Merlo MC, Hofer H, Gekle W, et al. Risperidone, 2mg/day vs. 4mg/day, in first-episode, acutely psychotic patients: treatment efficacy and effects on fine motor functioning. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):885-891.

33. Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, et al. Relationship between dopamine D2 occupancy, clinical response, and side effects: a double-blind PET study of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):514-520.

34. Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Medori R. Time course for antipsychotic treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):743-745.

35. Gallego JA, Robinson DG, Sevy SM, et al. Time to treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia: should acute treatment trials last several months? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1691-1696.

36. Gardner KN, Bostwick JR. Antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Am J Health Sys Pharm. 2012;69(21):1872-1879.

37. Stauffer VL, Case M, Kinon BJ, et al. Early response to antipsychotic therapy as a clinical marker of subsequent response in the treatment of patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(1-2):42-48.

38. Schennach-Wolff R, Seemüller FH, Mayr A, et al. An early improvement threshold to predict response and remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):460-466.

39. Perkins DO, Gu H, Weiden PJ, et al; Comparison of Atypicals in First Episode study group. Predictors of treatment discontinuation and medication nonadherence in patients recovering from a first episode of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder: a randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):106-113.

40. Garner B, Berger GE, Nicolo JP, et al. Pituitary volume and early treatment response in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis patients. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(1):65-71.

41. Sapra M, Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, et al. Reasons for adherence and nonadherence: a pilot study comparing first-and multi-episode schizophrenia patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;7(4):199-206.

The less time that passes between the onset of psychosis and initiation of appropriate treatment, the greater the patient’s odds of recovery.1 However, relapse prevention is a major clinical challenge because >80% of patients will relapse within 5 years, and, on average, 40% to 50% of patients with a first-episode schizophrenia will relapse within 2 years depending on the definition used and patient characteristics.2 Although there are several explanations and contributing factors to relapses, nonadherence—partial or complete discontinuation of antipsychotics—is a primary risk factor, contributing to a 5-fold increase in relapse risk.3

As such, optimal antipsychotic selection, dosing, and monitoring play an important role in managing this illness. Patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) are unusual in some ways, compared with patients with multiple episodes of psychosis and represent a different stage of schizophrenia.

In this 2-part series, we will discuss pharmacotherapy for FEP. This article focuses on antipsychotic selection, dosage, and duration of treatment among these patients. The second article, in the July 2015 issue, reviews the rationale and evidence for non-standard, first-line therapies, including long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine.

Defining FEP

FEP refers to a patient who has presented, been evaluated, and received treatment for the first psychotic episode associated with a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis.4 FEP is part of a trajectory marked by tran sitional periods. The patient transitions from being “healthy” to a prodromal state characterized by: (1) nonpsychotic behavioral disturbances such as depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder, (2) attenuated psychotic symptoms not requiring treatment, then converting to (3) psychotic symptoms prompting initial presentation for antipsychotic pharmacotherapy, leading to (4) a formal diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder and, subsequently, schizophrenia, requiring treatment to stabilize symptoms.

There are 2 critical periods along this continuum: prodromal stage and the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP). The prodromal period is a retrospectively identified time where the patient shows initial nonpsychotic disturbances (eg, cognitive and behavioral symptoms) before exhibiting clinical diagnostic criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Approximately one-third of patients exhibiting these symptoms convert to psychosis within 1 year, and early treatment engagement at this stage has been shown to improve outcomes.5 The DUP is the time from when a patient has noticeable psychotic symptoms to initiation of drug treatment. The DUP is a consistent predictor of clinical outcome in schizophrenia, including negative symptoms, quality of life, and functional capacity.1

Antipsychotic selection

Treatment goals for FEP patients include:

• minimizing the DUP

• rapidly stabilizing psychosis

• achieving full symptomatic remission

• preventing relapse.

Several treatment guidelines for managing schizophrenia offer variable recommendations for initial antipsychotic treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia (Table 1).6-15 Most recommend second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) over first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs)6,8,9,13,15 with specific recommendations on minimizing neurologic and metabolic adverse effects—to which FEP patients are susceptible—by avoiding high-potency and neurotoxic FGAs (eg, haloperidol and fluphenazine),7 clozapine,11,14 olanzapine,11 or ziprasidone.14 Two guidelines—the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network—do not state a preference for antipsychotic selection.10,12

The rationale for these recommendations is based on efficacy data, tolerability differences, FDA-approved indications, and recent FDA approvals with sparse post-marketing data. Of note, there are a lack of robust data for newer antipsychotics (eg, aripiprazole, paliperidone, iloperidone, asenapine, and lurasidone) in effectively and safely treating FEP; however, given the results of other antipsychotics studies, it is likely the efficacy and tolerability of these drugs can be extrapolated from experience with multi-episode patients.

Study design and demographics. Research studies of FEP share some similarities in study design; however, there is enough variability to make it difficult to compare studies and generalize findings (Table 2).16 The variability of DUP is a limitation when comparing studies because it is a significant predictor of clinical outcome. Patients who abuse substances—and often are more challenging to treat17—typically are excluded from these trials, which could explain the high response rate documented in studies of first-episode schizophrenia.

In addition, some FEP patients included in clinical trials might not be truly antipsychotic naïve; an estimated 25% to 75% of patients in these studies are antipsychotic naïve. This is an important consideration when comparing data on adverse effects that occur early in treatment. Additionally, acknowledging the advantages and disadvantages of how to handle missing data is critical because of the high dropout rate observed in these studies.18

Efficacy. There is a high response rate to antipsychotic therapy—ranging from 46% to 96%, depending on the study—in patients with first-episode schizophrenia.3 The response mainly is seen in reduction of positive symptoms because typically negative and cognitive symptoms do not respond to antipsychotics. One study reported only 29% of patients achieved both positive and negative symptom remission.19 It is likely that secondary negative symptoms caused by social withdrawal, reduced speech, and avoidance improve when positive symptoms subside, but primary negative symptoms endure.In general, there is a lack of evidence suggesting that 1 antipsychotic class or agent is more effective than another. Studies mainly assess effectiveness using the primary outcome measure of all-cause discontinuation, such as the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study.20 This outcome measure is a mixture of patient preference, tolerability, and efficacy that provides a more generalizable gauge on how well the treatment works in the clinic rather than tightly regulated settings such as clinical trials. A recent meta-analysis supports no differences in efficacy among antipsychotics in early-episode psychosis.21

Tolerability. Because there are no significant differences among antipsychotic classes or agents in terms of efficacy in first-episode schizophrenia, drug selection is guided mainly by (1) the adverse effect profile and (2) what should be avoided depending on patient-specific variables. Evidence suggests first-episode patients are more sensitive to adverse effects of antipsychotics, particularly neurologic side effects (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a table comparing adverse effects of antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis).18,22-29 Overall adverse effect profiles remain similar across FEP or multi-episode patients, but tend to be more exaggerated in drug-naïve patients with FEP.

Regarding FGA side effects, McEvoy et al18 demonstrated the neuroleptic threshold occurs at 50% lower haloperidol dosages in patients with first-episode schizophrenia (2.1 mg/d) compared with multi-episode schizophrenia (4.3 mg/d). Other trials suggest SGAs are associated with a lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) or use of adjunctive therapies such as anticholinergic drugs or benzodiazepines.23-27 An exception to this statement is that higher risperidone dosages (≥4 to 6 mg/d) have been found to have higher rates of EPS and use of adjunctive medications to treat these symptoms in FEP.26 This is important because studies report higher discontinuation rates with more severe adverse effects of antipsychotics.

Cardiometabolic effects are of particular concern in first-episode patients because most weight gain happens in the first 3 to 4 months of treatment and remains throughout the first year.18,24,29,30 Studies have shown that olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone are associated with more clinically significant weight gain compared with haloperidol and ziprasidone.23-25 Olanzapine-associated weight gain has been reported to be twice that of quetiapine and risperidone.18 Regardless, the EUFEST trial did not find a difference in clinically significant weight gain after 12 months among the antipsychotics studied, including haloperidol and ziprasidone.25

Weight gain associated with these antipsychotics is accompanied by changes in fasting triglycerides, glucose, total cholesterol,23 and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol as well as an increase in body mass index (BMI) categorization29 (eg, shift from normal to overweight).18,25 Patients with lower baseline BMI and in racial minority groups might experience more rapid weight gain regardless of antipsychotic selection.29,30

Hyperprolactinemia could be under-recognized and could contribute to early treatment discontinuation.31 Evidence in patients with first-episode schizophrenia suggests similar outcomes as those seen in multi-episode patients, in whom risperidone is associated with higher prolactin elevations and clinically significant hyperprolactinemia (eg, galactorrhea and gynecomastia) compared with olanzapine, quetiapine, and low-dose haloperidol.18,23,24 However, there is a lack of studies that assess whether long-term therapy with strong D2 receptor antagonists increases the risk of bone demineralization or pathological fractures when started before patients’ bones reach maximum density in their mid-20s.31

Antipsychotic dosing

Given the high rate of treatment response in FEP and patients’ higher sensitivity to antipsychotic adverse effects, particularly EPS, guidelines recommend antipsychotic dosages lower than those used for multi-episode schizophrenia,11 especially FGAs. Based on trial data, commonly used dosages include:

• haloperidol, ≤5 mg/d23-25,29

• olanzapine, 10 mg/d18,23,25,29

• risperidone, ≤4 to 6 mg/d.18,24,29,32

In general, haloperidol and risperidone, 2 to 3 mg/d, were well tolerated and effective in trials. Higher quetiapine dosages of 500 to 600 mg/d could be required.11,18,25

According to a survey on prescribing practices of antipsychotic selection and dosing in first-episode schizophrenia,4 clinical prescribing practices tend to use unnecessarily high initial antipsychotic dosing compared with trial data. There also is variability in the usual target antipsychotic dosage ranging from 50% lower dosages to normal dosages in chronic schizophrenia to above FDA-approved maximum dosages for olanzapine (which may be necessary to counteract tobacco-induced cytochrome P450 1A2 enzyme induction).

In addition, these clinicians reported prescribing aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with weaker evidence (eg, case reports, case series, open-label studies) supporting its efficacy and tolerability in FEP. These prescribing practices could reflect attempts to reduce the DUP and achieve symptom remission, so long as tolerability is not a concern.

Essentially, prescribed dosages should be based on symptom improvement and tolerability. This ideal dosage will vary as illustrated by Kapur et al,33 who reported that FEP patients (N = 20) given haloperidol, 1 mg or 2.5 mg/d, had D2 receptor occupancy rates of 38% to 87%, which was significantly dose-related (1 mg/d mean = 59%, 2.5 mg/d mean = 75%). Clinical response and EPS significantly increased as D2 receptor occupancy exceeded 65% and 78%, respectively.

Antipsychotic response

When should you expect to see symptom improvement in patients with first-episode schizophrenia?

Emsley et al34 reported a 77.6% response rate among first-episode patients (N = 522) treated with low dosages of risperidone (mean modal dosage [MMD] = 3.3 mg/d) and haloperidol (MMD = 2.9 mg/d). They found variable response times that were evenly dispersed over a 10-week period. Nearly one-quarter (22.5%) did not respond until after week 4 and 11.2% did not respond until after week 8. In a study of FEP patients (N = 112) treated with olanzapine (MMD = 11.8 mg/d) or risperidone (MMD = 3.9 mg/d), Gallego et al35 reported a cumulative response of 39.6% at week 8 and 65.1% at week 16.

Although there is evidence that, among multi-episode patients, early nonresponse to antipsychotic therapy could predict subsequent nonresponse,36 the evidence is mixed for first-episode schizophrenia. Studies by Emsley et al34 and Gallego et al35 did not find that early nonresponse at weeks 1 or 2 predicted subsequent nonresponse at week 4 or later. However, other studies support the idea that early nonresponse predicts subsequent nonresponse and early antipsychotic response predicts future response in first-episode patients, with good specificity and sensitivity.37,38

Overall, treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia is variable. An adequate antipsychotic trial may be longer, 8 to 16 weeks, compared with 4 to 8 weeks in multi-episode patients. Because research suggests that failure to respond to treatment may lead to medication nonadherence,39 it is reasonable to consider switching antipsychotics when a patient experiences minimal or no response to antipsychotic therapy at week 2; however, this should be a patient-specific decision.

How long should you continue therapy after symptom remission?

There is a lack of consensus on the duration of therapy for a patient treated for first-episode schizophrenia because a small percentage (10% to 20%) do not relapse after the first psychotic episode.3 In general, treatment guidelines and expert consensus statements recommend at least 1 to 2 years of treatment before considering a discontinuation trial.7,10-11 Discuss the benefits and risks of maintenance treatment with your patient and obtain informed consent. With patients with minimal insight, obtaining proper consent is not possible and the physician must exercise judgment unilaterally, if necessary, after educating the family.

After at least 12 months of treatment, antipsychotic therapy could continue indefinitely, depending on patient-specific factors. There are no predictors for identifying patients who do not require maintenance therapy beyond the first psychotic episode. The absence of negative and cognitive deficits could provide clues that a patient might be a candidate for antipsychotic tapering.

Predicting the treatment course

Research investigating clinical predictors or biomarkers that forecast whether a patient will respond to treatment is preliminary. Many characteristics have been identified (Table 31,3,4,23,25,40) and include shorter DUP,1 poorer premorbid function,3 antipsychotic discontinuation,3 a trusting patient-doctor relationship,41 and antipsychotic-related adverse effects,23,25 which are predictive of response, nonresponse, relapse, adherence, and nonadherence, respectively.

Bottom Line

The goals of pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia are to minimize the duration of untreated psychosis and target full remission of positive symptoms using the lowest possible antipsychotic dosages. Pharmacotherapy should continued for 1 to 2 years, with longer duration considered if it is discussed with the patient and with vigilant monitoring for adverse effects and suboptimal medication nonadherence to prevent relapse.

Editor’s note: The second article in this series in the July 2015 issue reviews the rationale and evidence for non-standard, first-line therapies, including long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine.

Related Resources

• Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project Early Treatment Program. National Institute of Mental Health. http://raiseetp.org.

• Martens L, Baker S. Promoting recovery from first episode psychosis: a guide for families. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/ Documents/www.camh.net/AboutCAMH/Guideto CAMH/MentalHealthPrograms/SchizophreniaProgram/ 3936PromotingRecoveryFirstEpisodePsychosisfinal.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Lurasidone • Latuda

Asenapine • Saphris Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Clozapine • Clozaril Paliperidone • Invega

Fluphenazine • Prolixin Quetiapine • Seroquel

Iloperidone • Fanapt Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Gardner reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Nasrallah is a consultant to Acadia, Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Sunovion, and is a speaker for Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, and Sunovion.

The less time that passes between the onset of psychosis and initiation of appropriate treatment, the greater the patient’s odds of recovery.1 However, relapse prevention is a major clinical challenge because >80% of patients will relapse within 5 years, and, on average, 40% to 50% of patients with a first-episode schizophrenia will relapse within 2 years depending on the definition used and patient characteristics.2 Although there are several explanations and contributing factors to relapses, nonadherence—partial or complete discontinuation of antipsychotics—is a primary risk factor, contributing to a 5-fold increase in relapse risk.3

As such, optimal antipsychotic selection, dosing, and monitoring play an important role in managing this illness. Patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) are unusual in some ways, compared with patients with multiple episodes of psychosis and represent a different stage of schizophrenia.

In this 2-part series, we will discuss pharmacotherapy for FEP. This article focuses on antipsychotic selection, dosage, and duration of treatment among these patients. The second article, in the July 2015 issue, reviews the rationale and evidence for non-standard, first-line therapies, including long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine.

Defining FEP

FEP refers to a patient who has presented, been evaluated, and received treatment for the first psychotic episode associated with a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis.4 FEP is part of a trajectory marked by tran sitional periods. The patient transitions from being “healthy” to a prodromal state characterized by: (1) nonpsychotic behavioral disturbances such as depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder, (2) attenuated psychotic symptoms not requiring treatment, then converting to (3) psychotic symptoms prompting initial presentation for antipsychotic pharmacotherapy, leading to (4) a formal diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder and, subsequently, schizophrenia, requiring treatment to stabilize symptoms.

There are 2 critical periods along this continuum: prodromal stage and the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP). The prodromal period is a retrospectively identified time where the patient shows initial nonpsychotic disturbances (eg, cognitive and behavioral symptoms) before exhibiting clinical diagnostic criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Approximately one-third of patients exhibiting these symptoms convert to psychosis within 1 year, and early treatment engagement at this stage has been shown to improve outcomes.5 The DUP is the time from when a patient has noticeable psychotic symptoms to initiation of drug treatment. The DUP is a consistent predictor of clinical outcome in schizophrenia, including negative symptoms, quality of life, and functional capacity.1

Antipsychotic selection

Treatment goals for FEP patients include:

• minimizing the DUP

• rapidly stabilizing psychosis

• achieving full symptomatic remission

• preventing relapse.

Several treatment guidelines for managing schizophrenia offer variable recommendations for initial antipsychotic treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia (Table 1).6-15 Most recommend second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) over first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs)6,8,9,13,15 with specific recommendations on minimizing neurologic and metabolic adverse effects—to which FEP patients are susceptible—by avoiding high-potency and neurotoxic FGAs (eg, haloperidol and fluphenazine),7 clozapine,11,14 olanzapine,11 or ziprasidone.14 Two guidelines—the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network—do not state a preference for antipsychotic selection.10,12

The rationale for these recommendations is based on efficacy data, tolerability differences, FDA-approved indications, and recent FDA approvals with sparse post-marketing data. Of note, there are a lack of robust data for newer antipsychotics (eg, aripiprazole, paliperidone, iloperidone, asenapine, and lurasidone) in effectively and safely treating FEP; however, given the results of other antipsychotics studies, it is likely the efficacy and tolerability of these drugs can be extrapolated from experience with multi-episode patients.

Study design and demographics. Research studies of FEP share some similarities in study design; however, there is enough variability to make it difficult to compare studies and generalize findings (Table 2).16 The variability of DUP is a limitation when comparing studies because it is a significant predictor of clinical outcome. Patients who abuse substances—and often are more challenging to treat17—typically are excluded from these trials, which could explain the high response rate documented in studies of first-episode schizophrenia.

In addition, some FEP patients included in clinical trials might not be truly antipsychotic naïve; an estimated 25% to 75% of patients in these studies are antipsychotic naïve. This is an important consideration when comparing data on adverse effects that occur early in treatment. Additionally, acknowledging the advantages and disadvantages of how to handle missing data is critical because of the high dropout rate observed in these studies.18

Efficacy. There is a high response rate to antipsychotic therapy—ranging from 46% to 96%, depending on the study—in patients with first-episode schizophrenia.3 The response mainly is seen in reduction of positive symptoms because typically negative and cognitive symptoms do not respond to antipsychotics. One study reported only 29% of patients achieved both positive and negative symptom remission.19 It is likely that secondary negative symptoms caused by social withdrawal, reduced speech, and avoidance improve when positive symptoms subside, but primary negative symptoms endure.In general, there is a lack of evidence suggesting that 1 antipsychotic class or agent is more effective than another. Studies mainly assess effectiveness using the primary outcome measure of all-cause discontinuation, such as the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study.20 This outcome measure is a mixture of patient preference, tolerability, and efficacy that provides a more generalizable gauge on how well the treatment works in the clinic rather than tightly regulated settings such as clinical trials. A recent meta-analysis supports no differences in efficacy among antipsychotics in early-episode psychosis.21

Tolerability. Because there are no significant differences among antipsychotic classes or agents in terms of efficacy in first-episode schizophrenia, drug selection is guided mainly by (1) the adverse effect profile and (2) what should be avoided depending on patient-specific variables. Evidence suggests first-episode patients are more sensitive to adverse effects of antipsychotics, particularly neurologic side effects (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a table comparing adverse effects of antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis).18,22-29 Overall adverse effect profiles remain similar across FEP or multi-episode patients, but tend to be more exaggerated in drug-naïve patients with FEP.

Regarding FGA side effects, McEvoy et al18 demonstrated the neuroleptic threshold occurs at 50% lower haloperidol dosages in patients with first-episode schizophrenia (2.1 mg/d) compared with multi-episode schizophrenia (4.3 mg/d). Other trials suggest SGAs are associated with a lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) or use of adjunctive therapies such as anticholinergic drugs or benzodiazepines.23-27 An exception to this statement is that higher risperidone dosages (≥4 to 6 mg/d) have been found to have higher rates of EPS and use of adjunctive medications to treat these symptoms in FEP.26 This is important because studies report higher discontinuation rates with more severe adverse effects of antipsychotics.

Cardiometabolic effects are of particular concern in first-episode patients because most weight gain happens in the first 3 to 4 months of treatment and remains throughout the first year.18,24,29,30 Studies have shown that olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone are associated with more clinically significant weight gain compared with haloperidol and ziprasidone.23-25 Olanzapine-associated weight gain has been reported to be twice that of quetiapine and risperidone.18 Regardless, the EUFEST trial did not find a difference in clinically significant weight gain after 12 months among the antipsychotics studied, including haloperidol and ziprasidone.25

Weight gain associated with these antipsychotics is accompanied by changes in fasting triglycerides, glucose, total cholesterol,23 and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol as well as an increase in body mass index (BMI) categorization29 (eg, shift from normal to overweight).18,25 Patients with lower baseline BMI and in racial minority groups might experience more rapid weight gain regardless of antipsychotic selection.29,30

Hyperprolactinemia could be under-recognized and could contribute to early treatment discontinuation.31 Evidence in patients with first-episode schizophrenia suggests similar outcomes as those seen in multi-episode patients, in whom risperidone is associated with higher prolactin elevations and clinically significant hyperprolactinemia (eg, galactorrhea and gynecomastia) compared with olanzapine, quetiapine, and low-dose haloperidol.18,23,24 However, there is a lack of studies that assess whether long-term therapy with strong D2 receptor antagonists increases the risk of bone demineralization or pathological fractures when started before patients’ bones reach maximum density in their mid-20s.31

Antipsychotic dosing

Given the high rate of treatment response in FEP and patients’ higher sensitivity to antipsychotic adverse effects, particularly EPS, guidelines recommend antipsychotic dosages lower than those used for multi-episode schizophrenia,11 especially FGAs. Based on trial data, commonly used dosages include:

• haloperidol, ≤5 mg/d23-25,29

• olanzapine, 10 mg/d18,23,25,29

• risperidone, ≤4 to 6 mg/d.18,24,29,32

In general, haloperidol and risperidone, 2 to 3 mg/d, were well tolerated and effective in trials. Higher quetiapine dosages of 500 to 600 mg/d could be required.11,18,25

According to a survey on prescribing practices of antipsychotic selection and dosing in first-episode schizophrenia,4 clinical prescribing practices tend to use unnecessarily high initial antipsychotic dosing compared with trial data. There also is variability in the usual target antipsychotic dosage ranging from 50% lower dosages to normal dosages in chronic schizophrenia to above FDA-approved maximum dosages for olanzapine (which may be necessary to counteract tobacco-induced cytochrome P450 1A2 enzyme induction).

In addition, these clinicians reported prescribing aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with weaker evidence (eg, case reports, case series, open-label studies) supporting its efficacy and tolerability in FEP. These prescribing practices could reflect attempts to reduce the DUP and achieve symptom remission, so long as tolerability is not a concern.

Essentially, prescribed dosages should be based on symptom improvement and tolerability. This ideal dosage will vary as illustrated by Kapur et al,33 who reported that FEP patients (N = 20) given haloperidol, 1 mg or 2.5 mg/d, had D2 receptor occupancy rates of 38% to 87%, which was significantly dose-related (1 mg/d mean = 59%, 2.5 mg/d mean = 75%). Clinical response and EPS significantly increased as D2 receptor occupancy exceeded 65% and 78%, respectively.

Antipsychotic response

When should you expect to see symptom improvement in patients with first-episode schizophrenia?

Emsley et al34 reported a 77.6% response rate among first-episode patients (N = 522) treated with low dosages of risperidone (mean modal dosage [MMD] = 3.3 mg/d) and haloperidol (MMD = 2.9 mg/d). They found variable response times that were evenly dispersed over a 10-week period. Nearly one-quarter (22.5%) did not respond until after week 4 and 11.2% did not respond until after week 8. In a study of FEP patients (N = 112) treated with olanzapine (MMD = 11.8 mg/d) or risperidone (MMD = 3.9 mg/d), Gallego et al35 reported a cumulative response of 39.6% at week 8 and 65.1% at week 16.

Although there is evidence that, among multi-episode patients, early nonresponse to antipsychotic therapy could predict subsequent nonresponse,36 the evidence is mixed for first-episode schizophrenia. Studies by Emsley et al34 and Gallego et al35 did not find that early nonresponse at weeks 1 or 2 predicted subsequent nonresponse at week 4 or later. However, other studies support the idea that early nonresponse predicts subsequent nonresponse and early antipsychotic response predicts future response in first-episode patients, with good specificity and sensitivity.37,38

Overall, treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia is variable. An adequate antipsychotic trial may be longer, 8 to 16 weeks, compared with 4 to 8 weeks in multi-episode patients. Because research suggests that failure to respond to treatment may lead to medication nonadherence,39 it is reasonable to consider switching antipsychotics when a patient experiences minimal or no response to antipsychotic therapy at week 2; however, this should be a patient-specific decision.

How long should you continue therapy after symptom remission?

There is a lack of consensus on the duration of therapy for a patient treated for first-episode schizophrenia because a small percentage (10% to 20%) do not relapse after the first psychotic episode.3 In general, treatment guidelines and expert consensus statements recommend at least 1 to 2 years of treatment before considering a discontinuation trial.7,10-11 Discuss the benefits and risks of maintenance treatment with your patient and obtain informed consent. With patients with minimal insight, obtaining proper consent is not possible and the physician must exercise judgment unilaterally, if necessary, after educating the family.

After at least 12 months of treatment, antipsychotic therapy could continue indefinitely, depending on patient-specific factors. There are no predictors for identifying patients who do not require maintenance therapy beyond the first psychotic episode. The absence of negative and cognitive deficits could provide clues that a patient might be a candidate for antipsychotic tapering.

Predicting the treatment course

Research investigating clinical predictors or biomarkers that forecast whether a patient will respond to treatment is preliminary. Many characteristics have been identified (Table 31,3,4,23,25,40) and include shorter DUP,1 poorer premorbid function,3 antipsychotic discontinuation,3 a trusting patient-doctor relationship,41 and antipsychotic-related adverse effects,23,25 which are predictive of response, nonresponse, relapse, adherence, and nonadherence, respectively.

Bottom Line

The goals of pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia are to minimize the duration of untreated psychosis and target full remission of positive symptoms using the lowest possible antipsychotic dosages. Pharmacotherapy should continued for 1 to 2 years, with longer duration considered if it is discussed with the patient and with vigilant monitoring for adverse effects and suboptimal medication nonadherence to prevent relapse.

Editor’s note: The second article in this series in the July 2015 issue reviews the rationale and evidence for non-standard, first-line therapies, including long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine.

Related Resources

• Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project Early Treatment Program. National Institute of Mental Health. http://raiseetp.org.

• Martens L, Baker S. Promoting recovery from first episode psychosis: a guide for families. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/ Documents/www.camh.net/AboutCAMH/Guideto CAMH/MentalHealthPrograms/SchizophreniaProgram/ 3936PromotingRecoveryFirstEpisodePsychosisfinal.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Lurasidone • Latuda

Asenapine • Saphris Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Clozapine • Clozaril Paliperidone • Invega

Fluphenazine • Prolixin Quetiapine • Seroquel

Iloperidone • Fanapt Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Gardner reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Nasrallah is a consultant to Acadia, Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Sunovion, and is a speaker for Alkermes, Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, and Sunovion.

1. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

2. Bradford DW, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. Pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia and related nonaffective psychoses. Drugs. 2003;63(21):2265-2283.

3. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following a response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

4. Weiden PJ, Buckley PF, Grody M. Understanding and treating “first-episode” schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(3):481-510.

5. Madaan V, Bestha DP, Kolli V. Schizophrenia prodrome: an optimal approach. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):16-20, 29-30.

6. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

7. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620.

8. Canadian Psychiatric Association. Clinical practice guideline. Treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(13 suppl 1):7S-57S.

9. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A. Treatment of schizophrenia 1999. Expert consensus guideline series. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 11):4-80.

10. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical guideline 178: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. London, United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2014.

11. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71-93.

12. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of schizophrenia. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2013. SIGN publication no. 131.

13. Argo TR, Crismon ML, Miller AL, et al. Texas Medication Algorithm Project procedural manual. Schizophrenia treatment algorithms. Austin, Texas: Texas Department of State Health Services; 2008.

14. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller Al, et al. The Mount Sinai conference on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):5-16.

15. Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9(4):248-312.

16. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psych. 1999;56(3):241-247.

17. Green AI, Tohen MF, Hamer RM, et al. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophr Res. 2004;66(2-3):125-135.

18. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7): 1050-1060.

19. Henry LP, Amminger GP, Harris MG, et al. The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):716-728.

20. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New Engl J Med. 2005; 353(12):1209-1223.

21. Crossley NA, Constante M, McGuire P, et al. Efficacy of atypical v. typical antipsychotics in the treatment of early psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):434-439.

22. McEvoy JP, Hogarty GE, Steingard S. Optimal dose of neuroleptic in acute schizophrenia: a controlled study of the neuroleptic threshold and higher haloperidol dose. Arch Gen Psych. 1991;48(8):739-745.

23. Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, et al; HGDH Study Group. Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1396-1404.

24. Schooler N, Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, et al; Early Psychosis Global Working Group. Risperidone and haloperidol in first-episode psychosis: a long-term randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):947-953.

25. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

26. Emsley RA; Risperidone Working Group. Risperidone in the treatment of first-episode psychotic patients: a double-blind multicenter study. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(4):721-729.

27. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naïve first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):995-1003.

28. Girgis RR, Phillips MR, Li X, et al. Clozapine v. chlorpromazine in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: 9-year outcomes of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):281-288.

29. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Napolitano B, et al. Randomized comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone for the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia: 4-month outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2096-2102.

30. Zipursky RB, Gu H, Green AI, et al. Course and predictors of weight gain in people with first-episode psychosis treated with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:537-543.

31. Taylor M, Waight A, Leonard B. Advances in the understanding and challenges facing the management of first-episode schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2012; 26(suppl 5):3-5.

32. Merlo MC, Hofer H, Gekle W, et al. Risperidone, 2mg/day vs. 4mg/day, in first-episode, acutely psychotic patients: treatment efficacy and effects on fine motor functioning. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):885-891.

33. Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, et al. Relationship between dopamine D2 occupancy, clinical response, and side effects: a double-blind PET study of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):514-520.

34. Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Medori R. Time course for antipsychotic treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):743-745.

35. Gallego JA, Robinson DG, Sevy SM, et al. Time to treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia: should acute treatment trials last several months? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1691-1696.

36. Gardner KN, Bostwick JR. Antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Am J Health Sys Pharm. 2012;69(21):1872-1879.

37. Stauffer VL, Case M, Kinon BJ, et al. Early response to antipsychotic therapy as a clinical marker of subsequent response in the treatment of patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(1-2):42-48.

38. Schennach-Wolff R, Seemüller FH, Mayr A, et al. An early improvement threshold to predict response and remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):460-466.

39. Perkins DO, Gu H, Weiden PJ, et al; Comparison of Atypicals in First Episode study group. Predictors of treatment discontinuation and medication nonadherence in patients recovering from a first episode of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder: a randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):106-113.

40. Garner B, Berger GE, Nicolo JP, et al. Pituitary volume and early treatment response in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis patients. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(1):65-71.

41. Sapra M, Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, et al. Reasons for adherence and nonadherence: a pilot study comparing first-and multi-episode schizophrenia patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;7(4):199-206.

1. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

2. Bradford DW, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. Pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia and related nonaffective psychoses. Drugs. 2003;63(21):2265-2283.

3. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following a response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241-247.

4. Weiden PJ, Buckley PF, Grody M. Understanding and treating “first-episode” schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(3):481-510.

5. Madaan V, Bestha DP, Kolli V. Schizophrenia prodrome: an optimal approach. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):16-20, 29-30.

6. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

7. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620.

8. Canadian Psychiatric Association. Clinical practice guideline. Treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(13 suppl 1):7S-57S.

9. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A. Treatment of schizophrenia 1999. Expert consensus guideline series. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 11):4-80.

10. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical guideline 178: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. London, United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2014.

11. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71-93.

12. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of schizophrenia. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2013. SIGN publication no. 131.

13. Argo TR, Crismon ML, Miller AL, et al. Texas Medication Algorithm Project procedural manual. Schizophrenia treatment algorithms. Austin, Texas: Texas Department of State Health Services; 2008.

14. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller Al, et al. The Mount Sinai conference on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):5-16.

15. Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9(4):248-312.

16. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psych. 1999;56(3):241-247.

17. Green AI, Tohen MF, Hamer RM, et al. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophr Res. 2004;66(2-3):125-135.

18. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7): 1050-1060.

19. Henry LP, Amminger GP, Harris MG, et al. The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):716-728.

20. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New Engl J Med. 2005; 353(12):1209-1223.

21. Crossley NA, Constante M, McGuire P, et al. Efficacy of atypical v. typical antipsychotics in the treatment of early psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):434-439.

22. McEvoy JP, Hogarty GE, Steingard S. Optimal dose of neuroleptic in acute schizophrenia: a controlled study of the neuroleptic threshold and higher haloperidol dose. Arch Gen Psych. 1991;48(8):739-745.

23. Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, et al; HGDH Study Group. Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1396-1404.

24. Schooler N, Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, et al; Early Psychosis Global Working Group. Risperidone and haloperidol in first-episode psychosis: a long-term randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):947-953.

25. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

26. Emsley RA; Risperidone Working Group. Risperidone in the treatment of first-episode psychotic patients: a double-blind multicenter study. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(4):721-729.

27. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naïve first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):995-1003.

28. Girgis RR, Phillips MR, Li X, et al. Clozapine v. chlorpromazine in treatment-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: 9-year outcomes of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):281-288.

29. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Napolitano B, et al. Randomized comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone for the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia: 4-month outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2096-2102.

30. Zipursky RB, Gu H, Green AI, et al. Course and predictors of weight gain in people with first-episode psychosis treated with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:537-543.

31. Taylor M, Waight A, Leonard B. Advances in the understanding and challenges facing the management of first-episode schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2012; 26(suppl 5):3-5.

32. Merlo MC, Hofer H, Gekle W, et al. Risperidone, 2mg/day vs. 4mg/day, in first-episode, acutely psychotic patients: treatment efficacy and effects on fine motor functioning. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):885-891.

33. Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, et al. Relationship between dopamine D2 occupancy, clinical response, and side effects: a double-blind PET study of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):514-520.

34. Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Medori R. Time course for antipsychotic treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):743-745.

35. Gallego JA, Robinson DG, Sevy SM, et al. Time to treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia: should acute treatment trials last several months? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1691-1696.

36. Gardner KN, Bostwick JR. Antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Am J Health Sys Pharm. 2012;69(21):1872-1879.

37. Stauffer VL, Case M, Kinon BJ, et al. Early response to antipsychotic therapy as a clinical marker of subsequent response in the treatment of patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(1-2):42-48.

38. Schennach-Wolff R, Seemüller FH, Mayr A, et al. An early improvement threshold to predict response and remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):460-466.

39. Perkins DO, Gu H, Weiden PJ, et al; Comparison of Atypicals in First Episode study group. Predictors of treatment discontinuation and medication nonadherence in patients recovering from a first episode of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder: a randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):106-113.

40. Garner B, Berger GE, Nicolo JP, et al. Pituitary volume and early treatment response in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis patients. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(1):65-71.

41. Sapra M, Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, et al. Reasons for adherence and nonadherence: a pilot study comparing first-and multi-episode schizophrenia patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;7(4):199-206.