User login

CASE Reckless driving, impulse buying

Mr. A, age 73, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit at a community hospital for evaluation of a psychotic episode. His admission to the unit was initiated by his primary care physician, who noted that Mr. A was “not making sense” during a routine visit. Mr. A was speaking rapidly about how he had discovered that high-dose omega-3 fatty acid supplements were a “cure” for Alzheimer’s disease. He also believes that he was recently appointed as CEO of Microsoft and Apple for his discoveries.

Three months earlier, Mr. A had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (10 to 15 g/d) because he believed they were the cure for memory problems, pain, and depression. At that time, he discontinued taking nortriptyline, 25 mg/d, and citalopram, 40 mg/d, which his outpatient psychiatrist had prescribed for major depressive disorder (MDD). Mr. A also had stopped taking buprenorphine, 2 mg, sublingual, 4 times a day, which he had been prescribed for chronic pain.

Mr. A’s wife reports that during the last 2 months, her husband had become irritable, impulsive, grandiose, and was sleeping very little. She added that although her husband’s ophthalmologist had advised him to not drive due to impaired vision, he had been driving recklessly across the metropolitan area. He had also spent nearly $15,000 buying furniture and other items for their home.

In addition to MDD, Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain. He has been taking vitamin D3, 2,000 U/d, as a nutritional supplement.

[polldaddy:10091672]

The authors’ observations

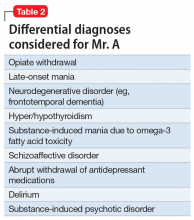

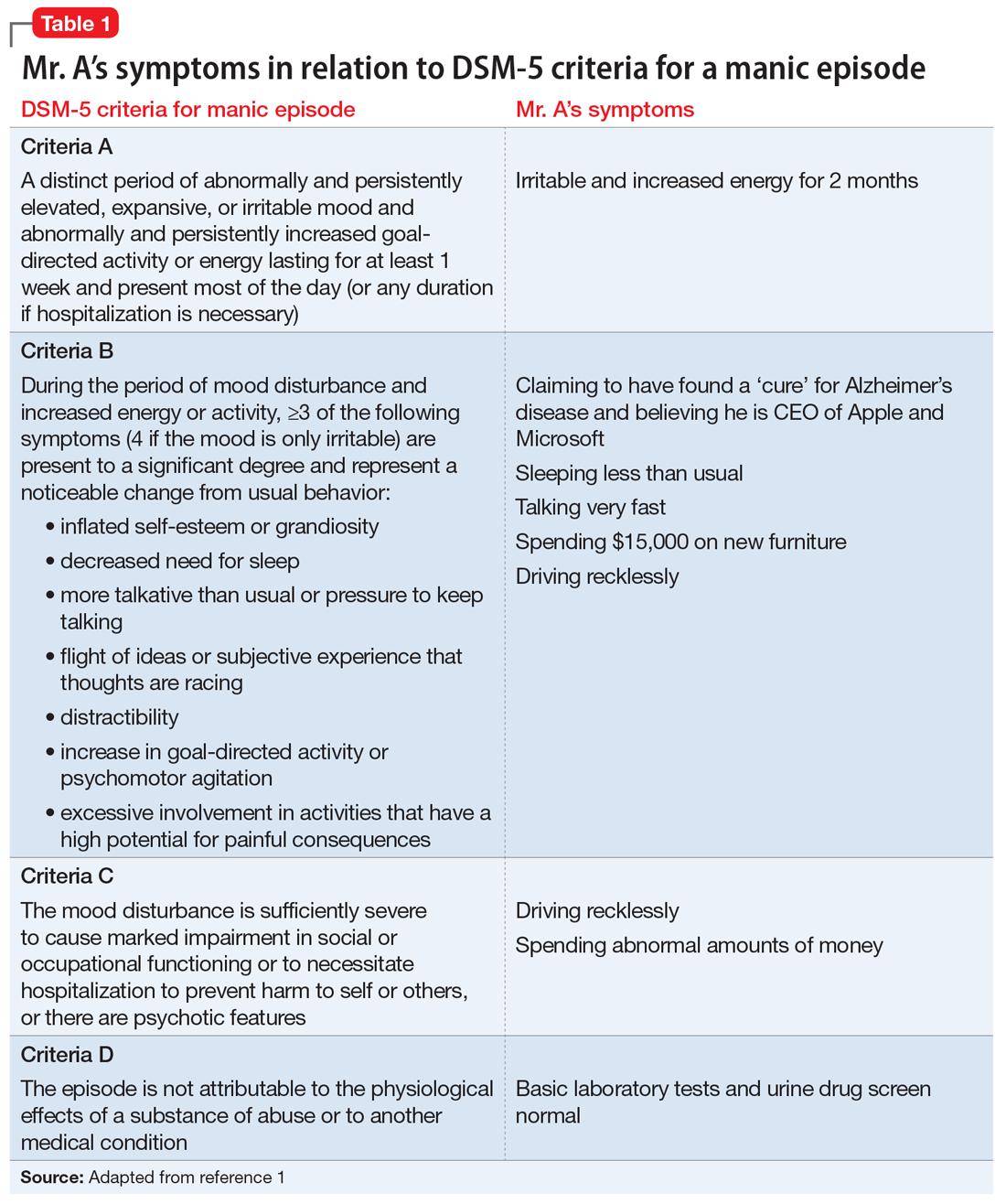

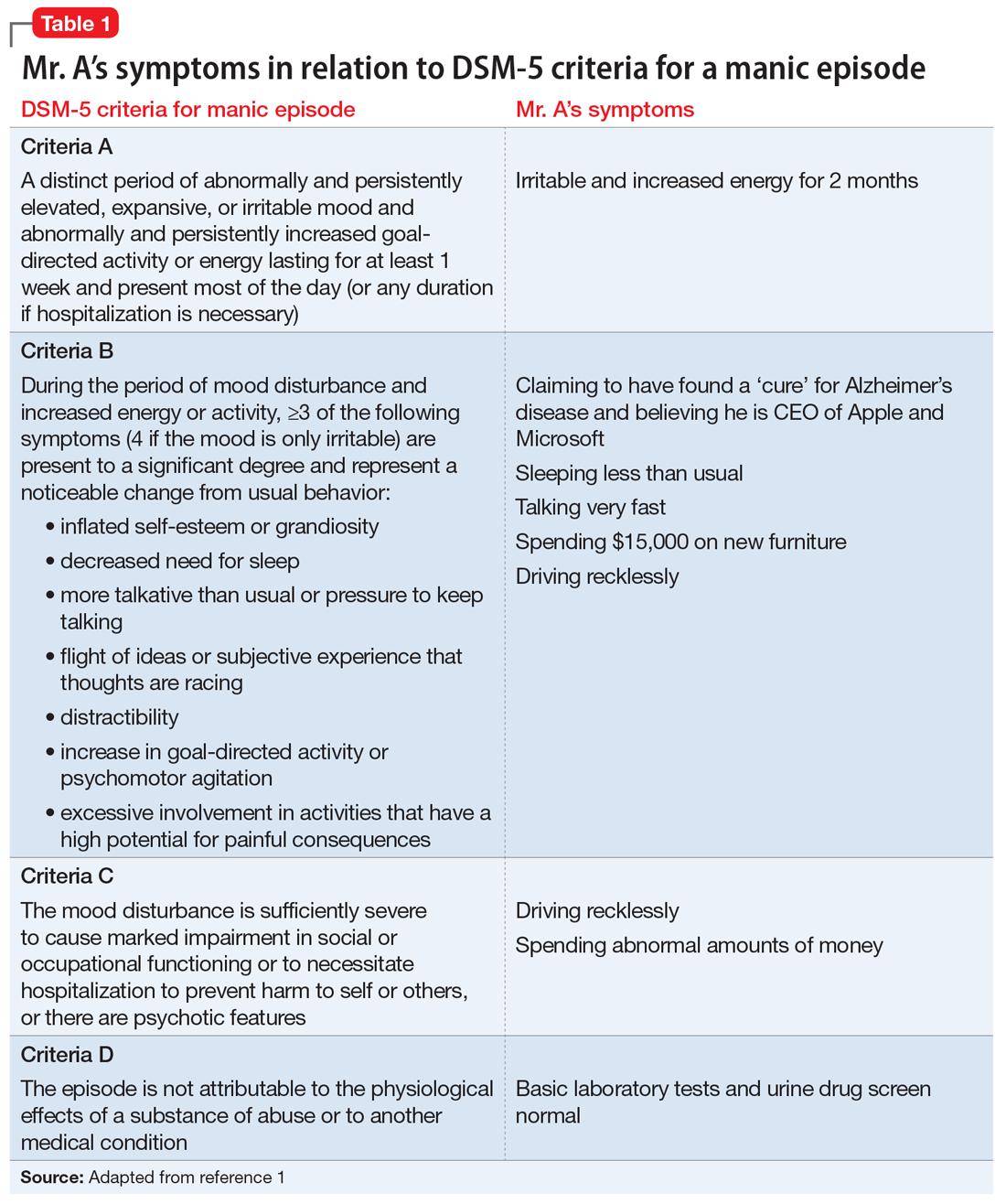

Mr. A met the DSM-5 criteria for a manic episode (Table 11). His manic and delusional symptoms are new. He has a long-standing diagnosis of MDD, which for many years had been successfully treated with antidepressants without a manic switch. The absence of a manic switch when treated with antidepressants without a mood stabilizer suggested that Mr. A did not have bipolarity in terms of a mood disorder diathesis.2 In addition, it would be unusual for an individual to develop a new-onset or primary bipolar disorder after age 60. Individuals in this age group who present with manic symptoms for the first time are preponderantly found to have a general medical or iatrogenic cause for the emergence of these symptoms.3 Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain.

Typically a sedentary man, Mr. A had been exhibiting disinhibited behavior, grandiosity, insomnia, and psychosis. These symptoms began 3 months before he was admitted to the psychiatric unit, when he had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Continue to: EVALUATION Persistent mania

EVALUATION Persistent mania

On initial examination, Mr. A is upset and irritable. He is casually dressed and well-groomed. He lacks insight and says he was brought to the hospital against his will, and it is his wife “who is the one who is crazy.” He is oriented to person, place, and time. At times he is found roaming the hallways, being intrusive, hyperverbal, and tangential with pressured speech. He is very difficult to redirect, and regularly interrupts the interview. His vital signs are stable. He walks well, with slow and steady gait, and displays no tremor or bradykinesia.

[polldaddy:10091674]

The authors’ observations

In order to rule out organic causes, a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid profile, urine drug screen, and brain MRI were ordered. No abnormalities were found. DHA and EPA levels were not measured because such testing was not available at the laboratory at the hospital.

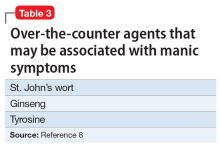

Mania emerging after the sixth decade of life is a rare occurrence. Therefore, we made a substantial effort to try to find another cause that might explain Mr. A’s unusual presentation (Table 2).

Omega-3 fatty acid–induced mania. The major types of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are EPA and DHA and their precursor, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). EPA and DHA are found primarily in fatty fish, such as salmon, and in fish oil supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids have beneficial anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and neuroplastic effects.4 Having properties similar to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, omega-3 fatty acids are thought to help prevent depression, have few interactions with other medications, and have a lower adverse-effect burden than antidepressants. They have been found to be beneficial as a maintenance treatment and for prevention of depressive episodes in bipolar depression, but no positive association has been found for bipolar mania.5

Continue to: However, very limited evidence suggests...

However, very limited evidence suggests that omega-3 fatty acid supplements, particularly those with flaxseed oil, can induce hypomania or mania. This association was first reported by Rudin6 in 1981, and later reported in other studies.7 How omega-3 fatty acids might induce mania is unclear.

Mr. A was reportedly taking high doses of an omega-3 fatty acid supplement. We hypothesized that the antidepressant effect of this supplement may have precipitated a manic episode. Mr. A had no history of manic episodes in the past and was stable during the treatment with the outpatient psychiatrist. A first episode mania in the seventh decade of life would be highly unusual without an organic etiology. After laboratory tests found no abnormalities that would point to an organic etiology, iatrogenic causes were considered. After a review of the literature, there was anecdotal evidence for the induction of mania in clinical trials studying the effects of omega-3 supplements on affective disorders.

This led us to ask: How much omega-3 fatty acid supplements, if any, can a patient with a depressive or bipolar disorder safely take? Currently, omega-3 fatty acid supplements are not FDA-approved for the treatment of depression or bipolar disorder. However, patients may take 1.5 to 2 g/d for MDD. Further research is needed to determine the optimal dose. It is unclear at this time if omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has any benefit in the acute or maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

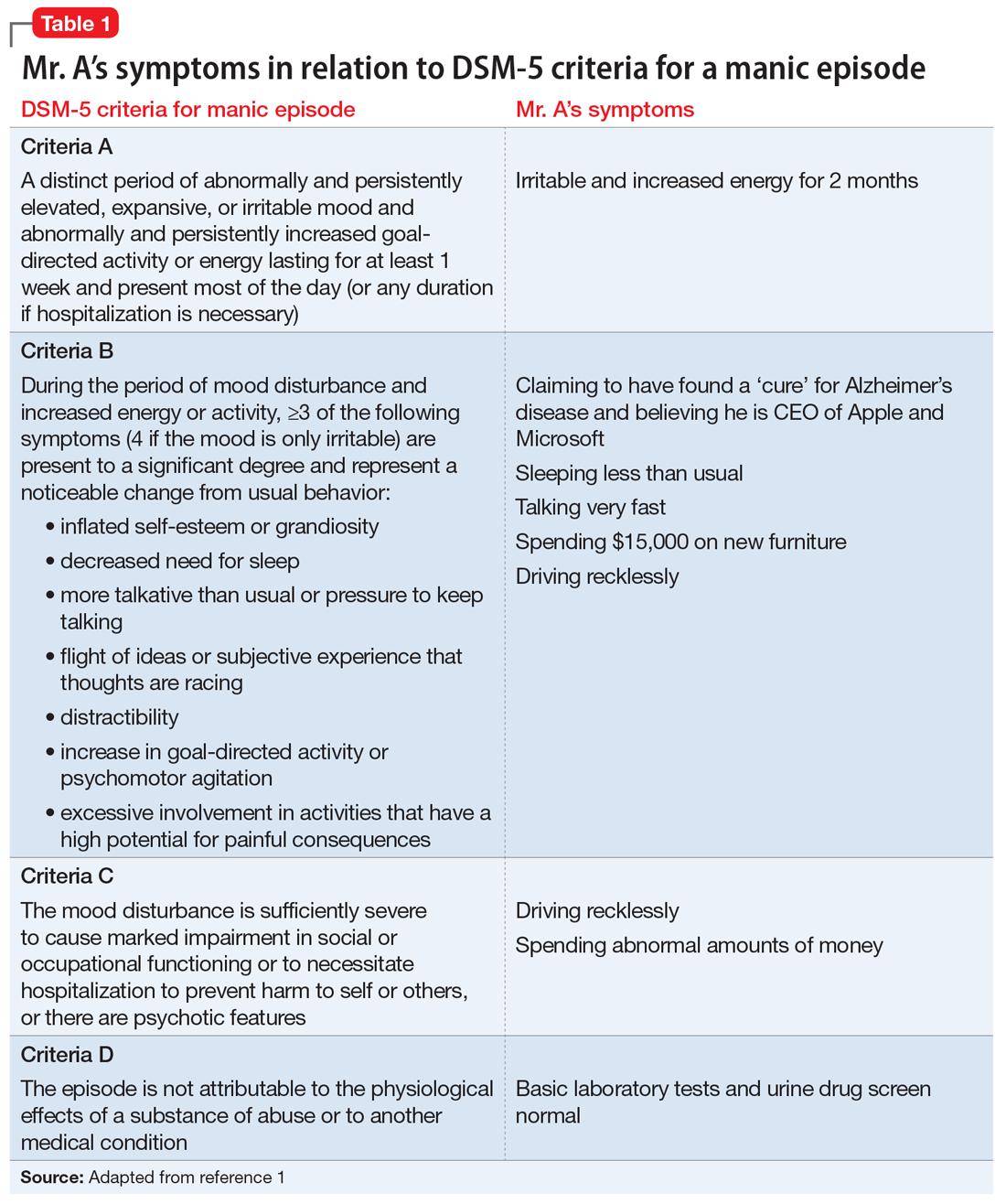

Alternative nutritional supplements for mood disorders. Traditionally, mood disorders, such as MDD and bipolar disorder, have been treated with psychotropic medications. However, through the years, sporadic studies have examined the efficacy of nutritional interventions as a cost-effective approach to preventing and treating these conditions.5 Proponents of this approach believe such supplements can increase efficacy, as well as decrease the required dose of psychotropic medications, thus potentially minimizing adverse effects. However, their overuse can pose a potential threat of toxicity or unexpected adverse effects, such as precipitation of mania. Table 38 lists over-the-counter nutritional and/or herbal agents that may cause mania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

On admission, Mr. A receives a dose of

[polldaddy:10091676]

The authors’ observations

During an acute manic episode, the goal of treatment is urgent mood stabilization. Monotherapy can be used; however, in emergent settings, a combination is often used for a rapid response. The most commonly used agents are lithium, anticonvulsants such as valproic acid, and antipsychotics.9 In addition, benzodiazepines can be used for insomnia, agitation, or anxiety. The decision to use lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic depends upon the specific medication’s adverse effects, the patient’s medical history, previous medication trials, drug–drug interactions, patient preference, and cost.

Because Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, lithium was contraindicated.

[polldaddy:10091678]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

After the acute episode of mania resolves, maintenance pharmacotherapy typically involves continuing the same regimen that achieved mood stabilization. Monotherapy is typically preferred to combination therapy, but it is not always possible after a manic episode.10 A reasonable approach is to slowly taper the antipsychotic after several months of dual therapy if symptoms continue to be well-controlled. Further adjustments may be necessary, depending on the medications’ adverse effects. Moreover, further acute episodes of mania or depression will also determine future treatment.

OUTCOME Resolution of delusions

Mr. A is discharged 30 days after admission. At this point, his acute manic episode has resolved with non-tangential, non-pressured speech, improved sleep, and decreased impulsivity. His grandiose delusions also have resolved. He is prescribed valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and risperidone, 6 mg/d at bedtime, under the care of his outpatient psychiatrist.

Bottom Line

Initial presentation of a manic episode in an older patient is rare. It is important to rule out organic causes. Weak evidence suggests omega-3 fatty acid supplements may have the potential to induce mania in certain patients.

Related Resource

- Ramaswamy S, Driscoll D, Rodriguez A, et al. Nutraceuticals for traumatic brain injury: Should you recommend their use? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(7):34-38,40,41-45.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Suboxone, Subutex

Citalopram • Celexa

Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam• Ativan

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495-553.

3. Sami M, Khan H, Nilforooshan R. Late onset mania as an organic syndrome: a review of case reports in the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015:188:226-231.

4. Su KP, Matsuoka Y, Pae CU. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of mood and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):129-137.

5. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

6. Rudin DO. The major psychoses and neuroses as omega-3 essential fatty acid deficiency syndrome: substrate pellagra. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(9):837-850.

7. Su KP, Shen WW, Huang SY. Are omega3 fatty acids beneficial in depression but not mania? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):716-717.

8. Joshi K, Faubion M. Mania and psychosis associated with St. John’s wort and ginseng. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(9):56-61.

9. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

10. Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, et al; Trial 127 Investigators. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a North American study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex (trial 127). Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):476-488.

CASE Reckless driving, impulse buying

Mr. A, age 73, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit at a community hospital for evaluation of a psychotic episode. His admission to the unit was initiated by his primary care physician, who noted that Mr. A was “not making sense” during a routine visit. Mr. A was speaking rapidly about how he had discovered that high-dose omega-3 fatty acid supplements were a “cure” for Alzheimer’s disease. He also believes that he was recently appointed as CEO of Microsoft and Apple for his discoveries.

Three months earlier, Mr. A had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (10 to 15 g/d) because he believed they were the cure for memory problems, pain, and depression. At that time, he discontinued taking nortriptyline, 25 mg/d, and citalopram, 40 mg/d, which his outpatient psychiatrist had prescribed for major depressive disorder (MDD). Mr. A also had stopped taking buprenorphine, 2 mg, sublingual, 4 times a day, which he had been prescribed for chronic pain.

Mr. A’s wife reports that during the last 2 months, her husband had become irritable, impulsive, grandiose, and was sleeping very little. She added that although her husband’s ophthalmologist had advised him to not drive due to impaired vision, he had been driving recklessly across the metropolitan area. He had also spent nearly $15,000 buying furniture and other items for their home.

In addition to MDD, Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain. He has been taking vitamin D3, 2,000 U/d, as a nutritional supplement.

[polldaddy:10091672]

The authors’ observations

Mr. A met the DSM-5 criteria for a manic episode (Table 11). His manic and delusional symptoms are new. He has a long-standing diagnosis of MDD, which for many years had been successfully treated with antidepressants without a manic switch. The absence of a manic switch when treated with antidepressants without a mood stabilizer suggested that Mr. A did not have bipolarity in terms of a mood disorder diathesis.2 In addition, it would be unusual for an individual to develop a new-onset or primary bipolar disorder after age 60. Individuals in this age group who present with manic symptoms for the first time are preponderantly found to have a general medical or iatrogenic cause for the emergence of these symptoms.3 Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain.

Typically a sedentary man, Mr. A had been exhibiting disinhibited behavior, grandiosity, insomnia, and psychosis. These symptoms began 3 months before he was admitted to the psychiatric unit, when he had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Continue to: EVALUATION Persistent mania

EVALUATION Persistent mania

On initial examination, Mr. A is upset and irritable. He is casually dressed and well-groomed. He lacks insight and says he was brought to the hospital against his will, and it is his wife “who is the one who is crazy.” He is oriented to person, place, and time. At times he is found roaming the hallways, being intrusive, hyperverbal, and tangential with pressured speech. He is very difficult to redirect, and regularly interrupts the interview. His vital signs are stable. He walks well, with slow and steady gait, and displays no tremor or bradykinesia.

[polldaddy:10091674]

The authors’ observations

In order to rule out organic causes, a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid profile, urine drug screen, and brain MRI were ordered. No abnormalities were found. DHA and EPA levels were not measured because such testing was not available at the laboratory at the hospital.

Mania emerging after the sixth decade of life is a rare occurrence. Therefore, we made a substantial effort to try to find another cause that might explain Mr. A’s unusual presentation (Table 2).

Omega-3 fatty acid–induced mania. The major types of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are EPA and DHA and their precursor, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). EPA and DHA are found primarily in fatty fish, such as salmon, and in fish oil supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids have beneficial anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and neuroplastic effects.4 Having properties similar to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, omega-3 fatty acids are thought to help prevent depression, have few interactions with other medications, and have a lower adverse-effect burden than antidepressants. They have been found to be beneficial as a maintenance treatment and for prevention of depressive episodes in bipolar depression, but no positive association has been found for bipolar mania.5

Continue to: However, very limited evidence suggests...

However, very limited evidence suggests that omega-3 fatty acid supplements, particularly those with flaxseed oil, can induce hypomania or mania. This association was first reported by Rudin6 in 1981, and later reported in other studies.7 How omega-3 fatty acids might induce mania is unclear.

Mr. A was reportedly taking high doses of an omega-3 fatty acid supplement. We hypothesized that the antidepressant effect of this supplement may have precipitated a manic episode. Mr. A had no history of manic episodes in the past and was stable during the treatment with the outpatient psychiatrist. A first episode mania in the seventh decade of life would be highly unusual without an organic etiology. After laboratory tests found no abnormalities that would point to an organic etiology, iatrogenic causes were considered. After a review of the literature, there was anecdotal evidence for the induction of mania in clinical trials studying the effects of omega-3 supplements on affective disorders.

This led us to ask: How much omega-3 fatty acid supplements, if any, can a patient with a depressive or bipolar disorder safely take? Currently, omega-3 fatty acid supplements are not FDA-approved for the treatment of depression or bipolar disorder. However, patients may take 1.5 to 2 g/d for MDD. Further research is needed to determine the optimal dose. It is unclear at this time if omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has any benefit in the acute or maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Alternative nutritional supplements for mood disorders. Traditionally, mood disorders, such as MDD and bipolar disorder, have been treated with psychotropic medications. However, through the years, sporadic studies have examined the efficacy of nutritional interventions as a cost-effective approach to preventing and treating these conditions.5 Proponents of this approach believe such supplements can increase efficacy, as well as decrease the required dose of psychotropic medications, thus potentially minimizing adverse effects. However, their overuse can pose a potential threat of toxicity or unexpected adverse effects, such as precipitation of mania. Table 38 lists over-the-counter nutritional and/or herbal agents that may cause mania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

On admission, Mr. A receives a dose of

[polldaddy:10091676]

The authors’ observations

During an acute manic episode, the goal of treatment is urgent mood stabilization. Monotherapy can be used; however, in emergent settings, a combination is often used for a rapid response. The most commonly used agents are lithium, anticonvulsants such as valproic acid, and antipsychotics.9 In addition, benzodiazepines can be used for insomnia, agitation, or anxiety. The decision to use lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic depends upon the specific medication’s adverse effects, the patient’s medical history, previous medication trials, drug–drug interactions, patient preference, and cost.

Because Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, lithium was contraindicated.

[polldaddy:10091678]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

After the acute episode of mania resolves, maintenance pharmacotherapy typically involves continuing the same regimen that achieved mood stabilization. Monotherapy is typically preferred to combination therapy, but it is not always possible after a manic episode.10 A reasonable approach is to slowly taper the antipsychotic after several months of dual therapy if symptoms continue to be well-controlled. Further adjustments may be necessary, depending on the medications’ adverse effects. Moreover, further acute episodes of mania or depression will also determine future treatment.

OUTCOME Resolution of delusions

Mr. A is discharged 30 days after admission. At this point, his acute manic episode has resolved with non-tangential, non-pressured speech, improved sleep, and decreased impulsivity. His grandiose delusions also have resolved. He is prescribed valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and risperidone, 6 mg/d at bedtime, under the care of his outpatient psychiatrist.

Bottom Line

Initial presentation of a manic episode in an older patient is rare. It is important to rule out organic causes. Weak evidence suggests omega-3 fatty acid supplements may have the potential to induce mania in certain patients.

Related Resource

- Ramaswamy S, Driscoll D, Rodriguez A, et al. Nutraceuticals for traumatic brain injury: Should you recommend their use? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(7):34-38,40,41-45.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Suboxone, Subutex

Citalopram • Celexa

Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam• Ativan

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproic acid • Depakote

CASE Reckless driving, impulse buying

Mr. A, age 73, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit at a community hospital for evaluation of a psychotic episode. His admission to the unit was initiated by his primary care physician, who noted that Mr. A was “not making sense” during a routine visit. Mr. A was speaking rapidly about how he had discovered that high-dose omega-3 fatty acid supplements were a “cure” for Alzheimer’s disease. He also believes that he was recently appointed as CEO of Microsoft and Apple for his discoveries.

Three months earlier, Mr. A had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (10 to 15 g/d) because he believed they were the cure for memory problems, pain, and depression. At that time, he discontinued taking nortriptyline, 25 mg/d, and citalopram, 40 mg/d, which his outpatient psychiatrist had prescribed for major depressive disorder (MDD). Mr. A also had stopped taking buprenorphine, 2 mg, sublingual, 4 times a day, which he had been prescribed for chronic pain.

Mr. A’s wife reports that during the last 2 months, her husband had become irritable, impulsive, grandiose, and was sleeping very little. She added that although her husband’s ophthalmologist had advised him to not drive due to impaired vision, he had been driving recklessly across the metropolitan area. He had also spent nearly $15,000 buying furniture and other items for their home.

In addition to MDD, Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain. He has been taking vitamin D3, 2,000 U/d, as a nutritional supplement.

[polldaddy:10091672]

The authors’ observations

Mr. A met the DSM-5 criteria for a manic episode (Table 11). His manic and delusional symptoms are new. He has a long-standing diagnosis of MDD, which for many years had been successfully treated with antidepressants without a manic switch. The absence of a manic switch when treated with antidepressants without a mood stabilizer suggested that Mr. A did not have bipolarity in terms of a mood disorder diathesis.2 In addition, it would be unusual for an individual to develop a new-onset or primary bipolar disorder after age 60. Individuals in this age group who present with manic symptoms for the first time are preponderantly found to have a general medical or iatrogenic cause for the emergence of these symptoms.3 Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain.

Typically a sedentary man, Mr. A had been exhibiting disinhibited behavior, grandiosity, insomnia, and psychosis. These symptoms began 3 months before he was admitted to the psychiatric unit, when he had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Continue to: EVALUATION Persistent mania

EVALUATION Persistent mania

On initial examination, Mr. A is upset and irritable. He is casually dressed and well-groomed. He lacks insight and says he was brought to the hospital against his will, and it is his wife “who is the one who is crazy.” He is oriented to person, place, and time. At times he is found roaming the hallways, being intrusive, hyperverbal, and tangential with pressured speech. He is very difficult to redirect, and regularly interrupts the interview. His vital signs are stable. He walks well, with slow and steady gait, and displays no tremor or bradykinesia.

[polldaddy:10091674]

The authors’ observations

In order to rule out organic causes, a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid profile, urine drug screen, and brain MRI were ordered. No abnormalities were found. DHA and EPA levels were not measured because such testing was not available at the laboratory at the hospital.

Mania emerging after the sixth decade of life is a rare occurrence. Therefore, we made a substantial effort to try to find another cause that might explain Mr. A’s unusual presentation (Table 2).

Omega-3 fatty acid–induced mania. The major types of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are EPA and DHA and their precursor, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). EPA and DHA are found primarily in fatty fish, such as salmon, and in fish oil supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids have beneficial anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and neuroplastic effects.4 Having properties similar to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, omega-3 fatty acids are thought to help prevent depression, have few interactions with other medications, and have a lower adverse-effect burden than antidepressants. They have been found to be beneficial as a maintenance treatment and for prevention of depressive episodes in bipolar depression, but no positive association has been found for bipolar mania.5

Continue to: However, very limited evidence suggests...

However, very limited evidence suggests that omega-3 fatty acid supplements, particularly those with flaxseed oil, can induce hypomania or mania. This association was first reported by Rudin6 in 1981, and later reported in other studies.7 How omega-3 fatty acids might induce mania is unclear.

Mr. A was reportedly taking high doses of an omega-3 fatty acid supplement. We hypothesized that the antidepressant effect of this supplement may have precipitated a manic episode. Mr. A had no history of manic episodes in the past and was stable during the treatment with the outpatient psychiatrist. A first episode mania in the seventh decade of life would be highly unusual without an organic etiology. After laboratory tests found no abnormalities that would point to an organic etiology, iatrogenic causes were considered. After a review of the literature, there was anecdotal evidence for the induction of mania in clinical trials studying the effects of omega-3 supplements on affective disorders.

This led us to ask: How much omega-3 fatty acid supplements, if any, can a patient with a depressive or bipolar disorder safely take? Currently, omega-3 fatty acid supplements are not FDA-approved for the treatment of depression or bipolar disorder. However, patients may take 1.5 to 2 g/d for MDD. Further research is needed to determine the optimal dose. It is unclear at this time if omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has any benefit in the acute or maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Alternative nutritional supplements for mood disorders. Traditionally, mood disorders, such as MDD and bipolar disorder, have been treated with psychotropic medications. However, through the years, sporadic studies have examined the efficacy of nutritional interventions as a cost-effective approach to preventing and treating these conditions.5 Proponents of this approach believe such supplements can increase efficacy, as well as decrease the required dose of psychotropic medications, thus potentially minimizing adverse effects. However, their overuse can pose a potential threat of toxicity or unexpected adverse effects, such as precipitation of mania. Table 38 lists over-the-counter nutritional and/or herbal agents that may cause mania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

On admission, Mr. A receives a dose of

[polldaddy:10091676]

The authors’ observations

During an acute manic episode, the goal of treatment is urgent mood stabilization. Monotherapy can be used; however, in emergent settings, a combination is often used for a rapid response. The most commonly used agents are lithium, anticonvulsants such as valproic acid, and antipsychotics.9 In addition, benzodiazepines can be used for insomnia, agitation, or anxiety. The decision to use lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic depends upon the specific medication’s adverse effects, the patient’s medical history, previous medication trials, drug–drug interactions, patient preference, and cost.

Because Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, lithium was contraindicated.

[polldaddy:10091678]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

After the acute episode of mania resolves, maintenance pharmacotherapy typically involves continuing the same regimen that achieved mood stabilization. Monotherapy is typically preferred to combination therapy, but it is not always possible after a manic episode.10 A reasonable approach is to slowly taper the antipsychotic after several months of dual therapy if symptoms continue to be well-controlled. Further adjustments may be necessary, depending on the medications’ adverse effects. Moreover, further acute episodes of mania or depression will also determine future treatment.

OUTCOME Resolution of delusions

Mr. A is discharged 30 days after admission. At this point, his acute manic episode has resolved with non-tangential, non-pressured speech, improved sleep, and decreased impulsivity. His grandiose delusions also have resolved. He is prescribed valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and risperidone, 6 mg/d at bedtime, under the care of his outpatient psychiatrist.

Bottom Line

Initial presentation of a manic episode in an older patient is rare. It is important to rule out organic causes. Weak evidence suggests omega-3 fatty acid supplements may have the potential to induce mania in certain patients.

Related Resource

- Ramaswamy S, Driscoll D, Rodriguez A, et al. Nutraceuticals for traumatic brain injury: Should you recommend their use? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(7):34-38,40,41-45.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Suboxone, Subutex

Citalopram • Celexa

Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam• Ativan

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495-553.

3. Sami M, Khan H, Nilforooshan R. Late onset mania as an organic syndrome: a review of case reports in the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015:188:226-231.

4. Su KP, Matsuoka Y, Pae CU. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of mood and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):129-137.

5. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

6. Rudin DO. The major psychoses and neuroses as omega-3 essential fatty acid deficiency syndrome: substrate pellagra. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(9):837-850.

7. Su KP, Shen WW, Huang SY. Are omega3 fatty acids beneficial in depression but not mania? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):716-717.

8. Joshi K, Faubion M. Mania and psychosis associated with St. John’s wort and ginseng. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(9):56-61.

9. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

10. Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, et al; Trial 127 Investigators. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a North American study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex (trial 127). Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):476-488.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495-553.

3. Sami M, Khan H, Nilforooshan R. Late onset mania as an organic syndrome: a review of case reports in the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015:188:226-231.

4. Su KP, Matsuoka Y, Pae CU. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of mood and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):129-137.

5. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

6. Rudin DO. The major psychoses and neuroses as omega-3 essential fatty acid deficiency syndrome: substrate pellagra. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(9):837-850.

7. Su KP, Shen WW, Huang SY. Are omega3 fatty acids beneficial in depression but not mania? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):716-717.

8. Joshi K, Faubion M. Mania and psychosis associated with St. John’s wort and ginseng. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(9):56-61.

9. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

10. Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, et al; Trial 127 Investigators. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a North American study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex (trial 127). Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):476-488.