User login

Background

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Immunosuppression, advanced age, and UV light exposure of fair skin are major risk factors; additionally, polyomavirus infection is detected in as many as 80% of cases.2-5 Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis.6 Approximately half of patients present with localized disease, in which surgical resection with or without adjuvant radiotherapy is usually indicated. However, overall prognosis is poor with MCC due to high recurrence rates.3

This neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes; distant metastasis also can occur, most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.7,8 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. The frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as high recurrence rates after treatment contribute to the overall poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25%, with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34% of cases; most recurrences occur within 2 years of diagnosis.8 The aggressiveness of the tumor determines patient mortality; in cases without lymph node involvement, the 5-year survival rate is 83.3%. However, the 5-year survival rate drops to 58.3% with lymph node involvement; in patients with metastatic disease, it is just 31.3%.8,9 Although MCC is a chemosensitive disease, durable responses are rarely seen in the advanced setting.3 Most patients with metastatic disease have a median progression-free survival of only 3 months.1

Presentation and Diagnosis

An MCC tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface, most often on the sun-exposed head and neck region.3,9-11 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% present on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.6 Unfortunately, this nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC can only be achieved with a skin biopsy, which allows for distinction from other clinically similar-appearing neoplasms.

Specific guidelines for an MCC diagnostic evaluation have been proposed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) based on a framework of clinical presentation, preliminary workup, diagnosis, and additional workup.12 The simplified algorithm for evaluation includes the following12,13:

- Examine skin and lymph nodes

- Obtain a biopsy specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin (including Breslow thickness and evidence of lymphovascular invasion) and immunostaining (including but not limited to cytokeratin (CK) 20 and thyroid transcription factor 1)

- Obtain a sentinel lymph node biopsy specimen from patients with negative clinical nodes, prior to excision when possible

- Perform fine-needle aspiration or core biopsy first for patients with positive clinical nodes; if negative, consider open biopsy, but if positive, proceed to next step

- Perform imaging as clinically indicated with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or positron emission tomography–computed tomography

- Consider consultation with a multidisciplinary tumor board

Histologic Features of MCC

Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.8,10 Immunohistochemical features include CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and CK7 negativity, which allows it to be differentiated from other neoplasms. Chromogranin and synaptophysin positivity provide further histologic confirmation. The absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.4,8

Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Other Risk Factors

Merkel cell carcinoma is frequently associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases.8 Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.10

Immunosuppression and UV-exposed fair skin also are considered major risk factors, which may be explained by the increase in MCPyV small T-antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.10 Moreover, as is seen in other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can hinder tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development as well as the potential for a worse prognosis.4,8 The precise incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear; it is possible that chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.4,8

Impact of Comorbidities on MCC

These risk factors were all observed in the case patient. However, it also is possible that his associated comorbidities also had an impact on the presentation of his disease.8 For example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis have been shown to have an elevated risk for the development of MCC.14 Moreover, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as would be expected in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by migrating to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.8,15 Testing for MCPyV was never performed in the case patient; however, it certainly would be prudent to do so in such a presentation. Additionally, further studies to determine the correlation of MCC to these disease processes are warranted.8

Given that MCC tends to affect an older population in which other notable comorbidities are not uncommon, the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients of any treatment plan are important considerations.8 In the case study, a combined regimen of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized. This regimen was well tolerated by the patient and successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination has been shown to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.6 In all high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize outcomes.

Bottom Line

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare but aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most frequently affects elderly patients, immunosuppressed patients, and individuals with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis also may play a role. In this case, the patient’s history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor. This potential risk should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. This unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission following treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

- O’Brien T, Power DG. Metastatic Merkel-cell carcinoma: the dawn of a new era. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11:2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224924.

- Del Marmol V, Lebbé C. New perspectives in Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:72-83.

- Garcia-Carbonero R, Marquez-Rodas I, de la Cruz-Merino L, et al. Recent therapeutic advances and change in treatment paradigm of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma [published online April 8, 2019]. Oncologist. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0718.

- Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

- Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

- Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

- Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

- Yousif J, Yousif B, Kuriata MA. Complete remission of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with severe psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;101:E24-E27.

- Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

- Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Merkel cell carcinoma. Published October 3, 2016. http://merkelcell.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/MccNccn.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

- Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

Background

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Immunosuppression, advanced age, and UV light exposure of fair skin are major risk factors; additionally, polyomavirus infection is detected in as many as 80% of cases.2-5 Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis.6 Approximately half of patients present with localized disease, in which surgical resection with or without adjuvant radiotherapy is usually indicated. However, overall prognosis is poor with MCC due to high recurrence rates.3

This neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes; distant metastasis also can occur, most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.7,8 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. The frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as high recurrence rates after treatment contribute to the overall poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25%, with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34% of cases; most recurrences occur within 2 years of diagnosis.8 The aggressiveness of the tumor determines patient mortality; in cases without lymph node involvement, the 5-year survival rate is 83.3%. However, the 5-year survival rate drops to 58.3% with lymph node involvement; in patients with metastatic disease, it is just 31.3%.8,9 Although MCC is a chemosensitive disease, durable responses are rarely seen in the advanced setting.3 Most patients with metastatic disease have a median progression-free survival of only 3 months.1

Presentation and Diagnosis

An MCC tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface, most often on the sun-exposed head and neck region.3,9-11 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% present on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.6 Unfortunately, this nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC can only be achieved with a skin biopsy, which allows for distinction from other clinically similar-appearing neoplasms.

Specific guidelines for an MCC diagnostic evaluation have been proposed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) based on a framework of clinical presentation, preliminary workup, diagnosis, and additional workup.12 The simplified algorithm for evaluation includes the following12,13:

- Examine skin and lymph nodes

- Obtain a biopsy specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin (including Breslow thickness and evidence of lymphovascular invasion) and immunostaining (including but not limited to cytokeratin (CK) 20 and thyroid transcription factor 1)

- Obtain a sentinel lymph node biopsy specimen from patients with negative clinical nodes, prior to excision when possible

- Perform fine-needle aspiration or core biopsy first for patients with positive clinical nodes; if negative, consider open biopsy, but if positive, proceed to next step

- Perform imaging as clinically indicated with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or positron emission tomography–computed tomography

- Consider consultation with a multidisciplinary tumor board

Histologic Features of MCC

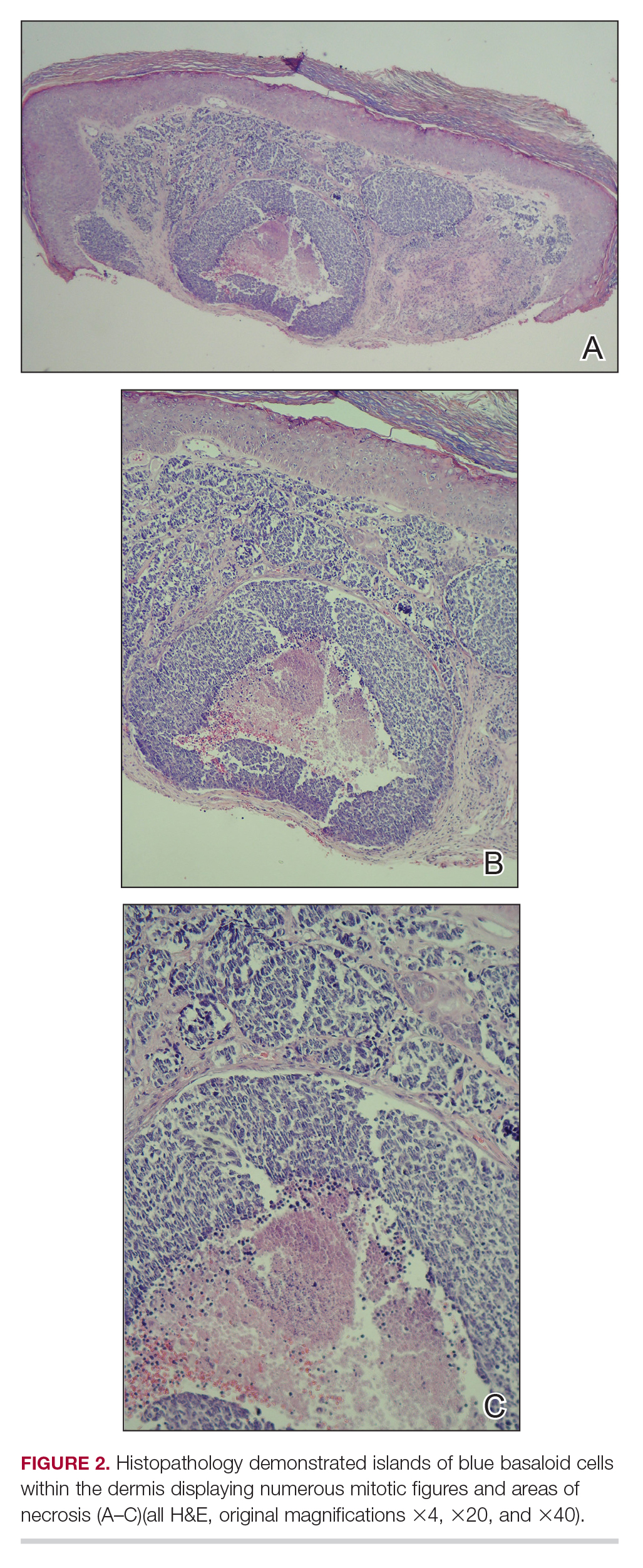

Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.8,10 Immunohistochemical features include CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and CK7 negativity, which allows it to be differentiated from other neoplasms. Chromogranin and synaptophysin positivity provide further histologic confirmation. The absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.4,8

Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Other Risk Factors

Merkel cell carcinoma is frequently associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases.8 Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.10

Immunosuppression and UV-exposed fair skin also are considered major risk factors, which may be explained by the increase in MCPyV small T-antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.10 Moreover, as is seen in other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can hinder tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development as well as the potential for a worse prognosis.4,8 The precise incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear; it is possible that chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.4,8

Impact of Comorbidities on MCC

These risk factors were all observed in the case patient. However, it also is possible that his associated comorbidities also had an impact on the presentation of his disease.8 For example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis have been shown to have an elevated risk for the development of MCC.14 Moreover, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as would be expected in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by migrating to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.8,15 Testing for MCPyV was never performed in the case patient; however, it certainly would be prudent to do so in such a presentation. Additionally, further studies to determine the correlation of MCC to these disease processes are warranted.8

Given that MCC tends to affect an older population in which other notable comorbidities are not uncommon, the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients of any treatment plan are important considerations.8 In the case study, a combined regimen of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized. This regimen was well tolerated by the patient and successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination has been shown to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.6 In all high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize outcomes.

Bottom Line

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare but aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most frequently affects elderly patients, immunosuppressed patients, and individuals with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis also may play a role. In this case, the patient’s history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor. This potential risk should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. This unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission following treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

Background

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Immunosuppression, advanced age, and UV light exposure of fair skin are major risk factors; additionally, polyomavirus infection is detected in as many as 80% of cases.2-5 Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis.6 Approximately half of patients present with localized disease, in which surgical resection with or without adjuvant radiotherapy is usually indicated. However, overall prognosis is poor with MCC due to high recurrence rates.3

This neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes; distant metastasis also can occur, most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.7,8 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. The frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as high recurrence rates after treatment contribute to the overall poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25%, with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34% of cases; most recurrences occur within 2 years of diagnosis.8 The aggressiveness of the tumor determines patient mortality; in cases without lymph node involvement, the 5-year survival rate is 83.3%. However, the 5-year survival rate drops to 58.3% with lymph node involvement; in patients with metastatic disease, it is just 31.3%.8,9 Although MCC is a chemosensitive disease, durable responses are rarely seen in the advanced setting.3 Most patients with metastatic disease have a median progression-free survival of only 3 months.1

Presentation and Diagnosis

An MCC tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface, most often on the sun-exposed head and neck region.3,9-11 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% present on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.6 Unfortunately, this nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC can only be achieved with a skin biopsy, which allows for distinction from other clinically similar-appearing neoplasms.

Specific guidelines for an MCC diagnostic evaluation have been proposed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) based on a framework of clinical presentation, preliminary workup, diagnosis, and additional workup.12 The simplified algorithm for evaluation includes the following12,13:

- Examine skin and lymph nodes

- Obtain a biopsy specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin (including Breslow thickness and evidence of lymphovascular invasion) and immunostaining (including but not limited to cytokeratin (CK) 20 and thyroid transcription factor 1)

- Obtain a sentinel lymph node biopsy specimen from patients with negative clinical nodes, prior to excision when possible

- Perform fine-needle aspiration or core biopsy first for patients with positive clinical nodes; if negative, consider open biopsy, but if positive, proceed to next step

- Perform imaging as clinically indicated with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or positron emission tomography–computed tomography

- Consider consultation with a multidisciplinary tumor board

Histologic Features of MCC

Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.8,10 Immunohistochemical features include CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and CK7 negativity, which allows it to be differentiated from other neoplasms. Chromogranin and synaptophysin positivity provide further histologic confirmation. The absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.4,8

Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Other Risk Factors

Merkel cell carcinoma is frequently associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases.8 Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.10

Immunosuppression and UV-exposed fair skin also are considered major risk factors, which may be explained by the increase in MCPyV small T-antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.10 Moreover, as is seen in other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can hinder tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development as well as the potential for a worse prognosis.4,8 The precise incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear; it is possible that chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.4,8

Impact of Comorbidities on MCC

These risk factors were all observed in the case patient. However, it also is possible that his associated comorbidities also had an impact on the presentation of his disease.8 For example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis have been shown to have an elevated risk for the development of MCC.14 Moreover, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as would be expected in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by migrating to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.8,15 Testing for MCPyV was never performed in the case patient; however, it certainly would be prudent to do so in such a presentation. Additionally, further studies to determine the correlation of MCC to these disease processes are warranted.8

Given that MCC tends to affect an older population in which other notable comorbidities are not uncommon, the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients of any treatment plan are important considerations.8 In the case study, a combined regimen of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized. This regimen was well tolerated by the patient and successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination has been shown to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.6 In all high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize outcomes.

Bottom Line

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare but aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most frequently affects elderly patients, immunosuppressed patients, and individuals with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis also may play a role. In this case, the patient’s history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor. This potential risk should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. This unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission following treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

- O’Brien T, Power DG. Metastatic Merkel-cell carcinoma: the dawn of a new era. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11:2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224924.

- Del Marmol V, Lebbé C. New perspectives in Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:72-83.

- Garcia-Carbonero R, Marquez-Rodas I, de la Cruz-Merino L, et al. Recent therapeutic advances and change in treatment paradigm of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma [published online April 8, 2019]. Oncologist. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0718.

- Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

- Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

- Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

- Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

- Yousif J, Yousif B, Kuriata MA. Complete remission of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with severe psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;101:E24-E27.

- Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

- Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Merkel cell carcinoma. Published October 3, 2016. http://merkelcell.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/MccNccn.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

- Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

- O’Brien T, Power DG. Metastatic Merkel-cell carcinoma: the dawn of a new era. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11:2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224924.

- Del Marmol V, Lebbé C. New perspectives in Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:72-83.

- Garcia-Carbonero R, Marquez-Rodas I, de la Cruz-Merino L, et al. Recent therapeutic advances and change in treatment paradigm of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma [published online April 8, 2019]. Oncologist. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0718.

- Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

- Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

- Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

- Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

- Yousif J, Yousif B, Kuriata MA. Complete remission of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with severe psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;101:E24-E27.

- Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

- Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Merkel cell carcinoma. Published October 3, 2016. http://merkelcell.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/MccNccn.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

- Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

The Case

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of the lesion, but his wife had recently noticed it; he denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. The patient had been on numerous treatment regimens for the control of psoriasis over the last 20 years, including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept at presentation of this new skin lesion. The use of immunosuppressive agents for his psoriasis provided an additional benefit of controlling the inflammatory arthritic disease.

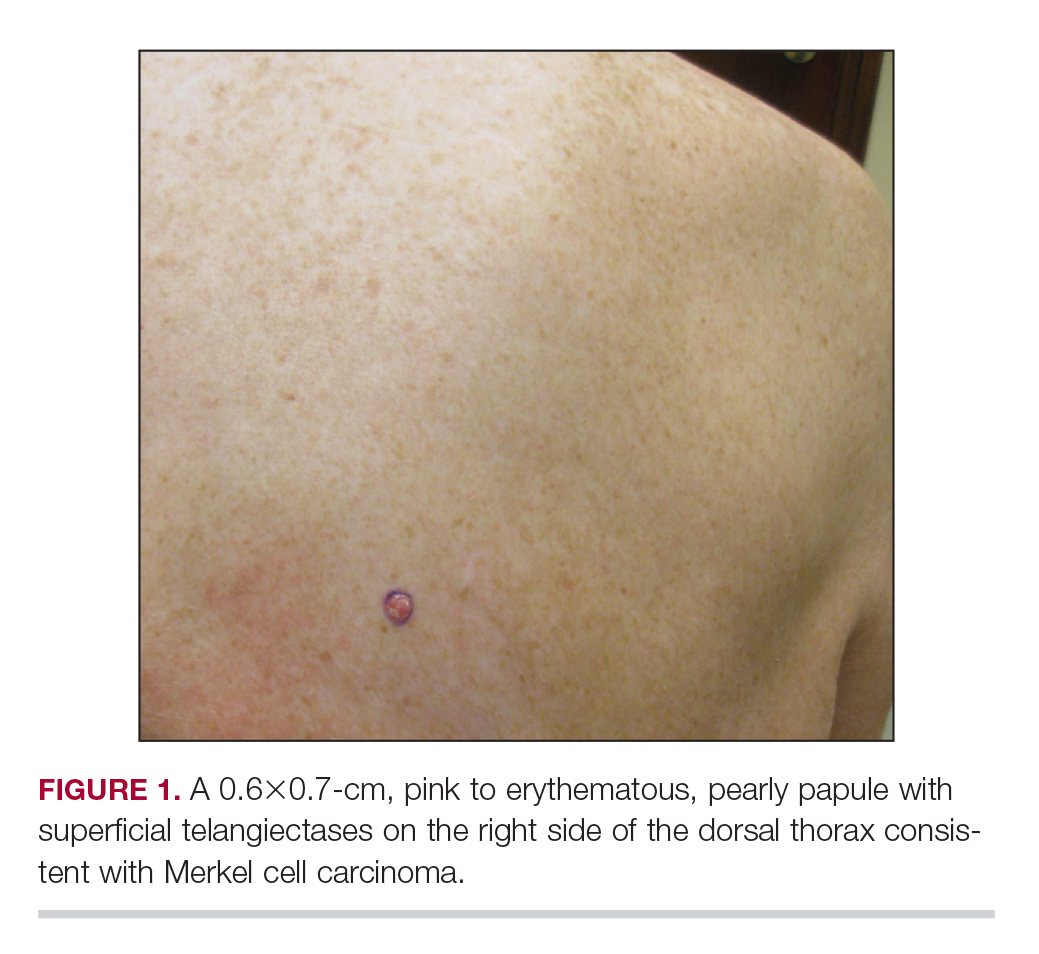

Physical examination revealed a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later, the patient returned to discuss the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and the patient was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

Treatment

He subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression. The patient underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.

Patient Outcome

Approximately 2.5 years after the second procedure, the patient began to develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain of an unclear etiology. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing areas of calcification and findings consistent with malignant lymphadenopathy. Multiple hepatic lesions also were noted, including a 9-cm lesion in the posterior right hepatic lobe. Computed tomography–guided biopsy of the liver lesion was performed, and the findings were consistent with metastatic MCC, indicating progression to stage IV disease. The patient was subsequently started on combination chemotherapeutic treatment with carboplatin and VP-16, with a planned treatment course of 4 to 6 cycles. He was able to complete a total of 6 cycles over a 4-month period and tolerated the treatment regimen fairly well. Follow-up positron emission tomography–computed tomography was within normal limits with no evidence of any hypermetabolic activity noted, indicating a complete radiographic remission of MCC. He was seen approximately 1 month after completion of treatment for clinical follow-up and monthly thereafter.

While on chemotherapy, the patient experienced a notable improvement in the psoriasis and psoriatic joint disease. Upon completion of chemotherapy, he was restarted on the same treatment plan that was utilized prior to surgery including topical corticosteroids, calcitriol, intramuscular steroid injections, and UVB phototherapy, which provided substantial control of psoriasis and arthritic joint disease. The patient later died, likely due to his multiple comorbidities.