User login

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a potentially lethal illness caused by the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The virus was first reported in 2012, when it was isolated from the sputum of a previously healthy man in Saudi Arabia who presented with acute pneumonia and subsequent renal failure with a fatal outcome.1 Retrospective studies subsequently identified an earlier outbreak that year involving 13 patients in Jordan, and since then cases have been reported in 25 countries across the Arabian Peninsula and in Asia, Europe, Africa, and the United States, with over 1,000 confirmed cases and 450 related deaths.2,3

At the time of this writing, two cases of MERS have been reported in the United States, both in May 2014. Both reported cases involved patients who had traveled from Saudi Arabia, and which did not result in secondary cases.4 Beginning in May 2015, the Republic of Korea had experienced the largest known outbreak of MERS outside the Arabian Peninsula, with over 100 cases.5

THE VIRUS

MERS-CoV is classified as a coronavirus, which is a family of single-stranded RNA viruses. In 2003, a previously unknown coronavirus (SARS-CoV) caused a global outbreak of pneumonia that resulted in approximately 800 deaths.6 The MERS-CoV virus attaches to dipeptidyl peptidase 4 to enter cells, and this receptor is believed to be critical for pathogenesis, as infection does not occur in its absence.7

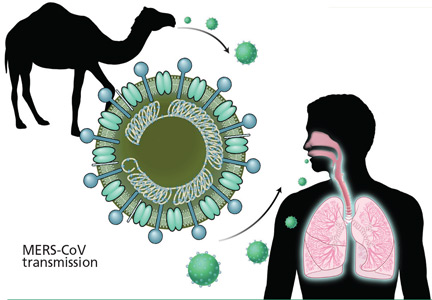

The source and mode of transmission to humans is not completely defined. Early reports suggested that MERS-CoV originated in bats, as RNA sequences related to MERS-CoV have been found in several bat species, but the virus itself has not been isolated from bats.8 Camels have been found to have a high rate of anti-MERS-CoV antibodies and to have the virus in nose swabs, and evidence for camel-to-human transmission has been presented.9–11 However, the precise role of camels and other animals as reservoirs or vectors of infection is still under investigation.

The incubation period from exposure to the development of clinical disease is estimated at 5 to 14 days.

For MERS-CoV, the basic reproduction ratio (R0), which measures the average number of secondary cases from each infected person, is estimated12 to be less than 0.7. In diseases in which the R0 is less than 1.0, infections occur in isolated clusters as limited chains of transmission, and thus the sustained transmission of MERS-CoV resulting in a large epidemic is thought to be unlikely. As a comparison, the median R0 value for seasonal influenza is estimated13 at 1.28. “Superspreading” may result in limited outbreaks of secondary cases; however, the continued epidemic spread of infection is thought to be unlikely.14 Nevertheless, viral adaptation with increased transmissibility remains a concern and a potential threat.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

MERS most commonly presents as a respiratory illness, although asymptomatic infection occurs. The percentage of patients who experience asymptomatic infection is unknown. A recent survey of 255 patients with laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV found that 64 (25.1%) were reported as asymptomatic at time of specimen collection. However, when 33 (52%) of those patients were interviewed, 26 (79%) reported at least one symptom that was consistent with a viral respiratory illness.15

For symptomatic patients, the initial complaints are nonspecific, beginning with fever, cough, sore throat, chills, and myalgia. Patients experiencing severe infection progress to dyspnea and pneumonia, with requirements for ventilatory support, vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy.16 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea have been reported in about one-third of patients.17

In a study of 47 patients with MERS-CoV, most of whom had underlying medical illnesses, 42 (89%) required intensive care and 34 (72%) required mechanical ventilation.17 The case-fatality rate in this study was 60%, but other studies have reported rates closer to 30%.15

Laboratory findings in patients with MERS-CoV infection usually include leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Severely ill patients may have evidence of acute kidney injury.

Radiographic findings of MERS are those of viral pneumonitis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Computed tomographic findings include ground-glass opacities, with peripheral lower-lobe preference.18

DIAGNOSIS

As MERS is a respiratory illness, sampling of respiratory secretions provides the highest yield for diagnosis. A study of 112 patients with MERS-CoV reported that polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of tracheal aspirates and bronchoalveolar lavage samples yielded significantly higher MERS-CoV loads than nasopharyngeal swab samples and sputum samples.19 However, upper respiratory tract testing is less invasive, and a positive nasopharyngeal swab result may obviate the need for further testing.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends collecting multiple specimens from different sites at different times after the onset of symptoms in order to increase the diagnostic yield. Specifically, it recommends testing a lower respiratory specimen (eg, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, tracheal aspirate), a nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab, and serum, using the CDC MERS-CoV rRT-PCR assay. In addition, for patients whose symptoms began more than 14 days earlier, the CDC also recommends testing a serum specimen with the CDC MERS-CoV serologic assay. As these guidelines are updated frequently, clinicians are advised to check the CDC website for the most up-to-date information (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html).20 The identification of MERS-CoV by virus isolation in cell culture is not recommended and, if pursued, must be performed in a biosafety level 3 facility. (Level 3 is the second-highest level of biosafety. The highest, level 4, is reserved for extremely dangerous agents such as Ebola virus).20

Given the nonspecific clinical presentation of MERS-CoV, clinicians may consider testing for other respiratory pathogens. A recent review of 54 travelers to California from MERS-CoV-affected areas found that while none tested positive for MERS-CoV, 32 (62%) of 52 travelers had other respiratory viruses.21 When testing for alternative pathogens, clinicians should order molecular or antigen-based detection methods.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, treatment for MERS is primarily supportive.

Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2b demonstrated activity in an animal model, but the regimen was ineffective when given a median of 19 (range 10–22) days after admission in 5 critically ill patients who subsequently died.22 A retrospective analysis comparing 20 patients with severe MERS-CoV who received ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a with 24 patients who did not reported that while survival was improved at 14 days, the mortality rates were similar at 28 days.23

A systematic review of treatments used for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) reported that most studies investigating steroid use were inconclusive and some showed possible harm, suggesting that systemic steroids should be avoided in coronavirus infections.24

PREVENTION

Healthcare-associated outbreaks of MERS are well described, and thus recognition of potential cases and prompt institution of appropriate infection control measures are critical.15,25

Healthcare providers should ask patients about recent travel history and ascertain if they meet the CDC criteria for a “patient under investigation” (PUI), ie, if they have both clinical features and an epidemiologic risk of MERS (Table 1). However, these recommendations for identification will assuredly change as the outbreak matures, and healthcare providers should refer to the CDC website for the most up-to-date information.

Once a PUI is identified, standard, contact, and airborne precautions are advised. These measures include performing hand hygiene and donning personal protective equipment, including gloves, gowns, eye protection, and respiratory protection (ie, a respirator) that is at least as protective as a fit-tested National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health-certified N95 filtering face-piece respirator. In addition, a patient with possible MERS should be placed in an airborne infection isolation room.

Traveler’s advice

The CDC does not currently recommend that Americans change their travel plans because of MERS. Clinicians performing pretravel evaluations should advise patients of current information on MERS. Patients at risk for MERS who develop a respiratory illness within 14 days of return should seek medical attention and inform healthcare providers of their travel history.

SUMMARY

Recent experience with SARS, Ebola virus disease, and now MERS-CoV highlights the impact of global air travel as a vector for the rapid worldwide dissemination of communicable diseases. Healthcare providers should elicit a travel history in all patients presenting with a febrile illness, as an infection acquired in one continent may not become manifest until the patient presents in another.

The scope of the current MERS-CoV outbreak is still evolving, with concerns that viral evolution could result in a SARS-like outbreak, as experienced almost a decade ago.

Healthcare providers are advised to screen patients at risk for MERS-CoV for respiratory symptoms, and to institute appropriate infection control measures. Through recognition and isolation, healthcare providers are at the front line in limiting the spread of this potentially lethal virus.

- Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1814–1820.

- Al-Abdallat MM, Payne DC, Alqasrawi S, et al. Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1225–1233.

- World Health Organization. Frequently asked questions on Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/faq/en/. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Bialek SR, Allen D, Alvarado-Ramy F, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). First confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in the United States, updated information on the epidemiology of MERS-CoV infection, and guidance for the public, clinicians, and public health authorities—May 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:431–436.

- World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Republic of Korea. www.who.int/csr/don/12-june-2015-mers-korea/en/. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Peiris JSM, Guan Y, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat Med 2004; 10:S88–S97.

- van Doremalen N, Miazqowicz KL, Milne-Price S, et al. Host species restriction of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus through its receptor, dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J Virol 2014; 88:9220–9232.

- Zumla A, Hui DS, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2015; S0140-6736(15)60454-604548 (Epub ahead of print).

- Meyer B, Muller MA, Corman WM, et al. Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20:552–559.

- Haagmans BL, Al Dhahiry SH, Reusken CB, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:140–145.

- Azhar EI, El-Kafrawy SA, Farraj SA, et al. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2499–2505.

- Chowell G, Blumberg S, Simonsen L, Miller MA, Viboud C. Synthesizing data and models for the spread of MERS-CoV, 2013: key role of index cases and hospital transmission. Epidemics 2014; 9:40–51.

- Biggerstaff M, Chauchemez S, Reed C, Gambhir M, Finelli L. Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2014: 14:480.

- Kucharski AJ, Althaus CL. The role of superspreading in Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) transmission. Euro Surveill 2015; 20.

- Oboho I, Tomczyk S, Al-Asmari A, et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah—a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:846–854.

- Arabi YM, Arifi AA, Balkhy HH, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:389–397.

- Assiri A, Al-Tawfig JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:752–761.

- Das KM, Lee EY, Enani MA, et al. CT correlation with outcomes in 15 patients with acute Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204:736–742.

- Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Makhdoom HQ, et al. Respiratory tract samples, viral load, and genome fraction yield in patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1590–1594.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from patients under investigation (PUIs) for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—version 2.1. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Shakhkarami M, Yen C, Glaser CA, Xia D, Watt J, Wadford DA. Laboratory testing for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, California, USA, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21: E-pub ahead of print. wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/9/15-0476_article. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Momattin H, Dib J, Memish ZA. Ribavirin and interferon therapy in patients infected with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: an observational study. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 20:42–46.

- Omrani AS, Saad MM, Baig K, et al. Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a for severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:1090–1095.

- Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner, P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med 2006; 3:e343.

- Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM, et al; KSA MERS-CoV Investigation Team. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:407–416.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a potentially lethal illness caused by the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The virus was first reported in 2012, when it was isolated from the sputum of a previously healthy man in Saudi Arabia who presented with acute pneumonia and subsequent renal failure with a fatal outcome.1 Retrospective studies subsequently identified an earlier outbreak that year involving 13 patients in Jordan, and since then cases have been reported in 25 countries across the Arabian Peninsula and in Asia, Europe, Africa, and the United States, with over 1,000 confirmed cases and 450 related deaths.2,3

At the time of this writing, two cases of MERS have been reported in the United States, both in May 2014. Both reported cases involved patients who had traveled from Saudi Arabia, and which did not result in secondary cases.4 Beginning in May 2015, the Republic of Korea had experienced the largest known outbreak of MERS outside the Arabian Peninsula, with over 100 cases.5

THE VIRUS

MERS-CoV is classified as a coronavirus, which is a family of single-stranded RNA viruses. In 2003, a previously unknown coronavirus (SARS-CoV) caused a global outbreak of pneumonia that resulted in approximately 800 deaths.6 The MERS-CoV virus attaches to dipeptidyl peptidase 4 to enter cells, and this receptor is believed to be critical for pathogenesis, as infection does not occur in its absence.7

The source and mode of transmission to humans is not completely defined. Early reports suggested that MERS-CoV originated in bats, as RNA sequences related to MERS-CoV have been found in several bat species, but the virus itself has not been isolated from bats.8 Camels have been found to have a high rate of anti-MERS-CoV antibodies and to have the virus in nose swabs, and evidence for camel-to-human transmission has been presented.9–11 However, the precise role of camels and other animals as reservoirs or vectors of infection is still under investigation.

The incubation period from exposure to the development of clinical disease is estimated at 5 to 14 days.

For MERS-CoV, the basic reproduction ratio (R0), which measures the average number of secondary cases from each infected person, is estimated12 to be less than 0.7. In diseases in which the R0 is less than 1.0, infections occur in isolated clusters as limited chains of transmission, and thus the sustained transmission of MERS-CoV resulting in a large epidemic is thought to be unlikely. As a comparison, the median R0 value for seasonal influenza is estimated13 at 1.28. “Superspreading” may result in limited outbreaks of secondary cases; however, the continued epidemic spread of infection is thought to be unlikely.14 Nevertheless, viral adaptation with increased transmissibility remains a concern and a potential threat.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

MERS most commonly presents as a respiratory illness, although asymptomatic infection occurs. The percentage of patients who experience asymptomatic infection is unknown. A recent survey of 255 patients with laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV found that 64 (25.1%) were reported as asymptomatic at time of specimen collection. However, when 33 (52%) of those patients were interviewed, 26 (79%) reported at least one symptom that was consistent with a viral respiratory illness.15

For symptomatic patients, the initial complaints are nonspecific, beginning with fever, cough, sore throat, chills, and myalgia. Patients experiencing severe infection progress to dyspnea and pneumonia, with requirements for ventilatory support, vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy.16 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea have been reported in about one-third of patients.17

In a study of 47 patients with MERS-CoV, most of whom had underlying medical illnesses, 42 (89%) required intensive care and 34 (72%) required mechanical ventilation.17 The case-fatality rate in this study was 60%, but other studies have reported rates closer to 30%.15

Laboratory findings in patients with MERS-CoV infection usually include leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Severely ill patients may have evidence of acute kidney injury.

Radiographic findings of MERS are those of viral pneumonitis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Computed tomographic findings include ground-glass opacities, with peripheral lower-lobe preference.18

DIAGNOSIS

As MERS is a respiratory illness, sampling of respiratory secretions provides the highest yield for diagnosis. A study of 112 patients with MERS-CoV reported that polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of tracheal aspirates and bronchoalveolar lavage samples yielded significantly higher MERS-CoV loads than nasopharyngeal swab samples and sputum samples.19 However, upper respiratory tract testing is less invasive, and a positive nasopharyngeal swab result may obviate the need for further testing.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends collecting multiple specimens from different sites at different times after the onset of symptoms in order to increase the diagnostic yield. Specifically, it recommends testing a lower respiratory specimen (eg, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, tracheal aspirate), a nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab, and serum, using the CDC MERS-CoV rRT-PCR assay. In addition, for patients whose symptoms began more than 14 days earlier, the CDC also recommends testing a serum specimen with the CDC MERS-CoV serologic assay. As these guidelines are updated frequently, clinicians are advised to check the CDC website for the most up-to-date information (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html).20 The identification of MERS-CoV by virus isolation in cell culture is not recommended and, if pursued, must be performed in a biosafety level 3 facility. (Level 3 is the second-highest level of biosafety. The highest, level 4, is reserved for extremely dangerous agents such as Ebola virus).20

Given the nonspecific clinical presentation of MERS-CoV, clinicians may consider testing for other respiratory pathogens. A recent review of 54 travelers to California from MERS-CoV-affected areas found that while none tested positive for MERS-CoV, 32 (62%) of 52 travelers had other respiratory viruses.21 When testing for alternative pathogens, clinicians should order molecular or antigen-based detection methods.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, treatment for MERS is primarily supportive.

Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2b demonstrated activity in an animal model, but the regimen was ineffective when given a median of 19 (range 10–22) days after admission in 5 critically ill patients who subsequently died.22 A retrospective analysis comparing 20 patients with severe MERS-CoV who received ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a with 24 patients who did not reported that while survival was improved at 14 days, the mortality rates were similar at 28 days.23

A systematic review of treatments used for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) reported that most studies investigating steroid use were inconclusive and some showed possible harm, suggesting that systemic steroids should be avoided in coronavirus infections.24

PREVENTION

Healthcare-associated outbreaks of MERS are well described, and thus recognition of potential cases and prompt institution of appropriate infection control measures are critical.15,25

Healthcare providers should ask patients about recent travel history and ascertain if they meet the CDC criteria for a “patient under investigation” (PUI), ie, if they have both clinical features and an epidemiologic risk of MERS (Table 1). However, these recommendations for identification will assuredly change as the outbreak matures, and healthcare providers should refer to the CDC website for the most up-to-date information.

Once a PUI is identified, standard, contact, and airborne precautions are advised. These measures include performing hand hygiene and donning personal protective equipment, including gloves, gowns, eye protection, and respiratory protection (ie, a respirator) that is at least as protective as a fit-tested National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health-certified N95 filtering face-piece respirator. In addition, a patient with possible MERS should be placed in an airborne infection isolation room.

Traveler’s advice

The CDC does not currently recommend that Americans change their travel plans because of MERS. Clinicians performing pretravel evaluations should advise patients of current information on MERS. Patients at risk for MERS who develop a respiratory illness within 14 days of return should seek medical attention and inform healthcare providers of their travel history.

SUMMARY

Recent experience with SARS, Ebola virus disease, and now MERS-CoV highlights the impact of global air travel as a vector for the rapid worldwide dissemination of communicable diseases. Healthcare providers should elicit a travel history in all patients presenting with a febrile illness, as an infection acquired in one continent may not become manifest until the patient presents in another.

The scope of the current MERS-CoV outbreak is still evolving, with concerns that viral evolution could result in a SARS-like outbreak, as experienced almost a decade ago.

Healthcare providers are advised to screen patients at risk for MERS-CoV for respiratory symptoms, and to institute appropriate infection control measures. Through recognition and isolation, healthcare providers are at the front line in limiting the spread of this potentially lethal virus.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a potentially lethal illness caused by the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The virus was first reported in 2012, when it was isolated from the sputum of a previously healthy man in Saudi Arabia who presented with acute pneumonia and subsequent renal failure with a fatal outcome.1 Retrospective studies subsequently identified an earlier outbreak that year involving 13 patients in Jordan, and since then cases have been reported in 25 countries across the Arabian Peninsula and in Asia, Europe, Africa, and the United States, with over 1,000 confirmed cases and 450 related deaths.2,3

At the time of this writing, two cases of MERS have been reported in the United States, both in May 2014. Both reported cases involved patients who had traveled from Saudi Arabia, and which did not result in secondary cases.4 Beginning in May 2015, the Republic of Korea had experienced the largest known outbreak of MERS outside the Arabian Peninsula, with over 100 cases.5

THE VIRUS

MERS-CoV is classified as a coronavirus, which is a family of single-stranded RNA viruses. In 2003, a previously unknown coronavirus (SARS-CoV) caused a global outbreak of pneumonia that resulted in approximately 800 deaths.6 The MERS-CoV virus attaches to dipeptidyl peptidase 4 to enter cells, and this receptor is believed to be critical for pathogenesis, as infection does not occur in its absence.7

The source and mode of transmission to humans is not completely defined. Early reports suggested that MERS-CoV originated in bats, as RNA sequences related to MERS-CoV have been found in several bat species, but the virus itself has not been isolated from bats.8 Camels have been found to have a high rate of anti-MERS-CoV antibodies and to have the virus in nose swabs, and evidence for camel-to-human transmission has been presented.9–11 However, the precise role of camels and other animals as reservoirs or vectors of infection is still under investigation.

The incubation period from exposure to the development of clinical disease is estimated at 5 to 14 days.

For MERS-CoV, the basic reproduction ratio (R0), which measures the average number of secondary cases from each infected person, is estimated12 to be less than 0.7. In diseases in which the R0 is less than 1.0, infections occur in isolated clusters as limited chains of transmission, and thus the sustained transmission of MERS-CoV resulting in a large epidemic is thought to be unlikely. As a comparison, the median R0 value for seasonal influenza is estimated13 at 1.28. “Superspreading” may result in limited outbreaks of secondary cases; however, the continued epidemic spread of infection is thought to be unlikely.14 Nevertheless, viral adaptation with increased transmissibility remains a concern and a potential threat.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

MERS most commonly presents as a respiratory illness, although asymptomatic infection occurs. The percentage of patients who experience asymptomatic infection is unknown. A recent survey of 255 patients with laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV found that 64 (25.1%) were reported as asymptomatic at time of specimen collection. However, when 33 (52%) of those patients were interviewed, 26 (79%) reported at least one symptom that was consistent with a viral respiratory illness.15

For symptomatic patients, the initial complaints are nonspecific, beginning with fever, cough, sore throat, chills, and myalgia. Patients experiencing severe infection progress to dyspnea and pneumonia, with requirements for ventilatory support, vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy.16 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea have been reported in about one-third of patients.17

In a study of 47 patients with MERS-CoV, most of whom had underlying medical illnesses, 42 (89%) required intensive care and 34 (72%) required mechanical ventilation.17 The case-fatality rate in this study was 60%, but other studies have reported rates closer to 30%.15

Laboratory findings in patients with MERS-CoV infection usually include leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Severely ill patients may have evidence of acute kidney injury.

Radiographic findings of MERS are those of viral pneumonitis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Computed tomographic findings include ground-glass opacities, with peripheral lower-lobe preference.18

DIAGNOSIS

As MERS is a respiratory illness, sampling of respiratory secretions provides the highest yield for diagnosis. A study of 112 patients with MERS-CoV reported that polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of tracheal aspirates and bronchoalveolar lavage samples yielded significantly higher MERS-CoV loads than nasopharyngeal swab samples and sputum samples.19 However, upper respiratory tract testing is less invasive, and a positive nasopharyngeal swab result may obviate the need for further testing.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends collecting multiple specimens from different sites at different times after the onset of symptoms in order to increase the diagnostic yield. Specifically, it recommends testing a lower respiratory specimen (eg, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, tracheal aspirate), a nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab, and serum, using the CDC MERS-CoV rRT-PCR assay. In addition, for patients whose symptoms began more than 14 days earlier, the CDC also recommends testing a serum specimen with the CDC MERS-CoV serologic assay. As these guidelines are updated frequently, clinicians are advised to check the CDC website for the most up-to-date information (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html).20 The identification of MERS-CoV by virus isolation in cell culture is not recommended and, if pursued, must be performed in a biosafety level 3 facility. (Level 3 is the second-highest level of biosafety. The highest, level 4, is reserved for extremely dangerous agents such as Ebola virus).20

Given the nonspecific clinical presentation of MERS-CoV, clinicians may consider testing for other respiratory pathogens. A recent review of 54 travelers to California from MERS-CoV-affected areas found that while none tested positive for MERS-CoV, 32 (62%) of 52 travelers had other respiratory viruses.21 When testing for alternative pathogens, clinicians should order molecular or antigen-based detection methods.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, treatment for MERS is primarily supportive.

Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2b demonstrated activity in an animal model, but the regimen was ineffective when given a median of 19 (range 10–22) days after admission in 5 critically ill patients who subsequently died.22 A retrospective analysis comparing 20 patients with severe MERS-CoV who received ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a with 24 patients who did not reported that while survival was improved at 14 days, the mortality rates were similar at 28 days.23

A systematic review of treatments used for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) reported that most studies investigating steroid use were inconclusive and some showed possible harm, suggesting that systemic steroids should be avoided in coronavirus infections.24

PREVENTION

Healthcare-associated outbreaks of MERS are well described, and thus recognition of potential cases and prompt institution of appropriate infection control measures are critical.15,25

Healthcare providers should ask patients about recent travel history and ascertain if they meet the CDC criteria for a “patient under investigation” (PUI), ie, if they have both clinical features and an epidemiologic risk of MERS (Table 1). However, these recommendations for identification will assuredly change as the outbreak matures, and healthcare providers should refer to the CDC website for the most up-to-date information.

Once a PUI is identified, standard, contact, and airborne precautions are advised. These measures include performing hand hygiene and donning personal protective equipment, including gloves, gowns, eye protection, and respiratory protection (ie, a respirator) that is at least as protective as a fit-tested National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health-certified N95 filtering face-piece respirator. In addition, a patient with possible MERS should be placed in an airborne infection isolation room.

Traveler’s advice

The CDC does not currently recommend that Americans change their travel plans because of MERS. Clinicians performing pretravel evaluations should advise patients of current information on MERS. Patients at risk for MERS who develop a respiratory illness within 14 days of return should seek medical attention and inform healthcare providers of their travel history.

SUMMARY

Recent experience with SARS, Ebola virus disease, and now MERS-CoV highlights the impact of global air travel as a vector for the rapid worldwide dissemination of communicable diseases. Healthcare providers should elicit a travel history in all patients presenting with a febrile illness, as an infection acquired in one continent may not become manifest until the patient presents in another.

The scope of the current MERS-CoV outbreak is still evolving, with concerns that viral evolution could result in a SARS-like outbreak, as experienced almost a decade ago.

Healthcare providers are advised to screen patients at risk for MERS-CoV for respiratory symptoms, and to institute appropriate infection control measures. Through recognition and isolation, healthcare providers are at the front line in limiting the spread of this potentially lethal virus.

- Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1814–1820.

- Al-Abdallat MM, Payne DC, Alqasrawi S, et al. Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1225–1233.

- World Health Organization. Frequently asked questions on Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/faq/en/. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Bialek SR, Allen D, Alvarado-Ramy F, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). First confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in the United States, updated information on the epidemiology of MERS-CoV infection, and guidance for the public, clinicians, and public health authorities—May 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:431–436.

- World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Republic of Korea. www.who.int/csr/don/12-june-2015-mers-korea/en/. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Peiris JSM, Guan Y, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat Med 2004; 10:S88–S97.

- van Doremalen N, Miazqowicz KL, Milne-Price S, et al. Host species restriction of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus through its receptor, dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J Virol 2014; 88:9220–9232.

- Zumla A, Hui DS, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2015; S0140-6736(15)60454-604548 (Epub ahead of print).

- Meyer B, Muller MA, Corman WM, et al. Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20:552–559.

- Haagmans BL, Al Dhahiry SH, Reusken CB, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:140–145.

- Azhar EI, El-Kafrawy SA, Farraj SA, et al. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2499–2505.

- Chowell G, Blumberg S, Simonsen L, Miller MA, Viboud C. Synthesizing data and models for the spread of MERS-CoV, 2013: key role of index cases and hospital transmission. Epidemics 2014; 9:40–51.

- Biggerstaff M, Chauchemez S, Reed C, Gambhir M, Finelli L. Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2014: 14:480.

- Kucharski AJ, Althaus CL. The role of superspreading in Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) transmission. Euro Surveill 2015; 20.

- Oboho I, Tomczyk S, Al-Asmari A, et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah—a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:846–854.

- Arabi YM, Arifi AA, Balkhy HH, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:389–397.

- Assiri A, Al-Tawfig JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:752–761.

- Das KM, Lee EY, Enani MA, et al. CT correlation with outcomes in 15 patients with acute Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204:736–742.

- Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Makhdoom HQ, et al. Respiratory tract samples, viral load, and genome fraction yield in patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1590–1594.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from patients under investigation (PUIs) for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—version 2.1. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Shakhkarami M, Yen C, Glaser CA, Xia D, Watt J, Wadford DA. Laboratory testing for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, California, USA, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21: E-pub ahead of print. wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/9/15-0476_article. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Momattin H, Dib J, Memish ZA. Ribavirin and interferon therapy in patients infected with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: an observational study. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 20:42–46.

- Omrani AS, Saad MM, Baig K, et al. Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a for severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:1090–1095.

- Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner, P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med 2006; 3:e343.

- Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM, et al; KSA MERS-CoV Investigation Team. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:407–416.

- Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1814–1820.

- Al-Abdallat MM, Payne DC, Alqasrawi S, et al. Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1225–1233.

- World Health Organization. Frequently asked questions on Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/faq/en/. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Bialek SR, Allen D, Alvarado-Ramy F, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). First confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in the United States, updated information on the epidemiology of MERS-CoV infection, and guidance for the public, clinicians, and public health authorities—May 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:431–436.

- World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Republic of Korea. www.who.int/csr/don/12-june-2015-mers-korea/en/. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Peiris JSM, Guan Y, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat Med 2004; 10:S88–S97.

- van Doremalen N, Miazqowicz KL, Milne-Price S, et al. Host species restriction of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus through its receptor, dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J Virol 2014; 88:9220–9232.

- Zumla A, Hui DS, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2015; S0140-6736(15)60454-604548 (Epub ahead of print).

- Meyer B, Muller MA, Corman WM, et al. Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20:552–559.

- Haagmans BL, Al Dhahiry SH, Reusken CB, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:140–145.

- Azhar EI, El-Kafrawy SA, Farraj SA, et al. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2499–2505.

- Chowell G, Blumberg S, Simonsen L, Miller MA, Viboud C. Synthesizing data and models for the spread of MERS-CoV, 2013: key role of index cases and hospital transmission. Epidemics 2014; 9:40–51.

- Biggerstaff M, Chauchemez S, Reed C, Gambhir M, Finelli L. Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2014: 14:480.

- Kucharski AJ, Althaus CL. The role of superspreading in Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) transmission. Euro Surveill 2015; 20.

- Oboho I, Tomczyk S, Al-Asmari A, et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah—a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:846–854.

- Arabi YM, Arifi AA, Balkhy HH, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:389–397.

- Assiri A, Al-Tawfig JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:752–761.

- Das KM, Lee EY, Enani MA, et al. CT correlation with outcomes in 15 patients with acute Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204:736–742.

- Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Makhdoom HQ, et al. Respiratory tract samples, viral load, and genome fraction yield in patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1590–1594.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from patients under investigation (PUIs) for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—version 2.1. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Shakhkarami M, Yen C, Glaser CA, Xia D, Watt J, Wadford DA. Laboratory testing for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, California, USA, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21: E-pub ahead of print. wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/9/15-0476_article. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Momattin H, Dib J, Memish ZA. Ribavirin and interferon therapy in patients infected with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: an observational study. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 20:42–46.

- Omrani AS, Saad MM, Baig K, et al. Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a for severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:1090–1095.

- Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner, P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med 2006; 3:e343.

- Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM, et al; KSA MERS-CoV Investigation Team. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:407–416.

KEY POINTS

- In MERS, initial complaints are of fever, cough, chills and myalgia. In a subset of patients, usually those with underlying illnesses, the disease can progress to fulminant sepsis with respiratory and renal failure and death.

- Healthcare providers should regularly visit the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for current information on countries experiencing a MERS outbreak, and for advice on how to identify a potentially infected patient.

- MERS-CoV has caused several healthcare-related outbreaks, so prompt identification and isolation of infected patients is critical to limiting the spread of infection. A “patient under identification” (ie, a person who has both clinical features and an epidemiologic risk) should be cared for under standard, contact, and airborne precautions.