User login

suggests a randomized trial conducted in Japan.

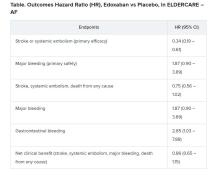

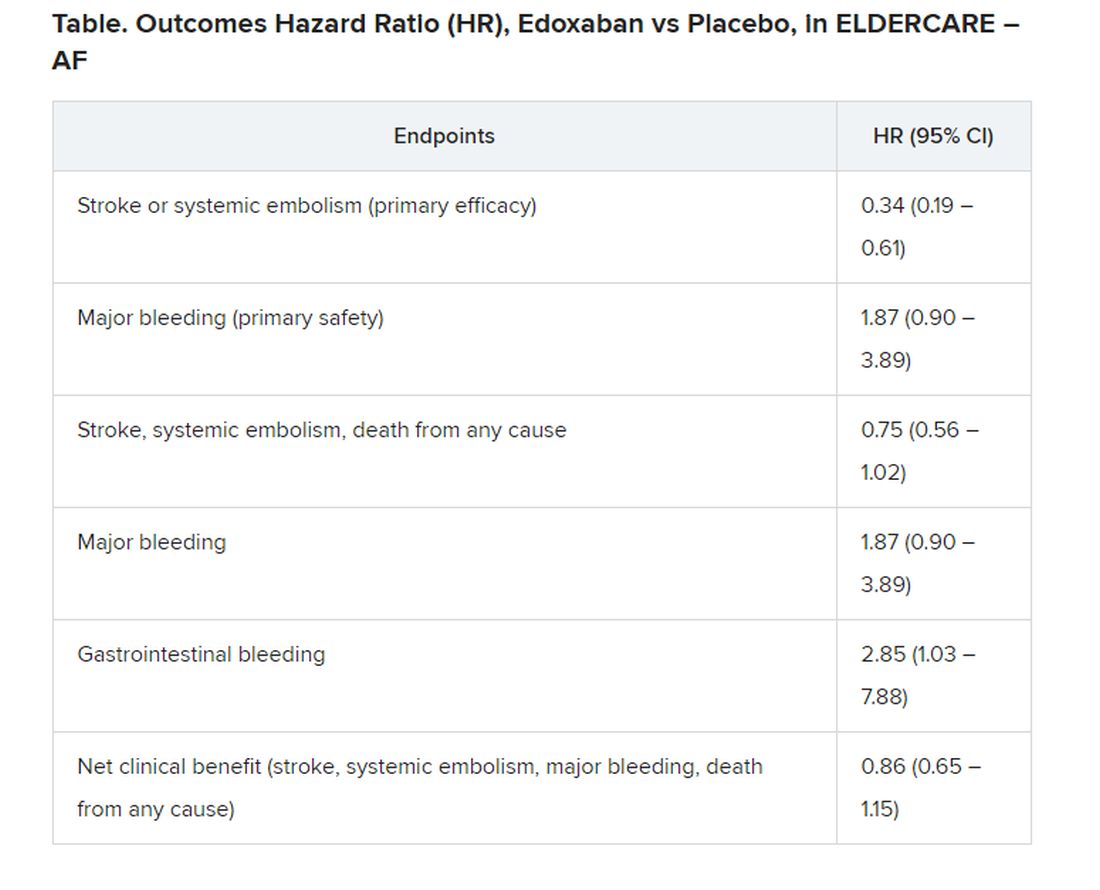

Many of the study’s 984 mostly octogenarian patients were objectively frail with poor renal function, low body weight, a history of serious bleeding, or other conditions that made them poor candidates for regular-dose oral anticoagulation. Yet those who took the factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) at the off-label dosage of 15 mg once daily showed a two-thirds drop in risk for stroke or systemic embolism (P < .001), compared with patients who received placebo. There were no fatal bleeds and virtually no intracranial hemorrhages.

For such high-risk patients with nonvalvular AFib who otherwise would not be given an OAC, edoxaban 15 mg “can be an acceptable treatment option in decreasing the risk of devastating stroke”; however, “it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, so care should be given in every patient,” said Ken Okumura, MD, PhD. Indeed, the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding tripled among the patients who received edoxaban, compared with those given placebo, at about 2.3% per year versus 0.8% per year.

Although their 87% increased risk for major bleeding did not reach significance, it hit close, with a P value of .09 in the trial, called Edoxaban Low-Dose for Elder Care Atrial Fibrillation Patients (ELDERCARE-AF).

Dr. Okumura, of Saiseikai Kumamoto (Japan) Hospital, presented the study August 30 during the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He is lead author of an article describing the study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many patients with AFib suffer strokes if they are not given oral anticoagulation because of “fear of major bleeding caused by standard OAC therapy,” Dr. Okumura noted. Others are inappropriately administered antiplatelets or anticoagulants at conventional dosages. “There is no standard of practice in Japan for patients like those in the present trial,” Dr. Okumura said. “However, I believe the present study opens a new possible path of thromboprophylaxis in such high-risk patients.”

Even with its relatively few bleeding events, ELDERCARE-AF “does suggest that the risk of the worst types of bleeds is not that high,” said Daniel E. Singer, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Gastrointestinal bleeding is annoying, and it will probably stop people from taking their edoxaban, but for the most part it doesn’t kill people.”

Moreover, he added, the trial suggests that low-dose edoxaban, in exchange for a steep reduction in thromboembolic risk, “doesn’t add to your risk of intracranial hemorrhage!”

ELDERCARE-AF may give practitioners “yet another reason to rethink” whether a low-dose DOAC such as edoxaban 15 mg/day may well be a good approach for such patients with AFib who are not receiving standard-dose OAC because of a perceived high risk for serious bleeding, said Dr. Singer, who was not involved in the study.

The trial randomly and evenly assigned 984 patients with AF in Japan to take either edoxaban 15 mg/day or placebo. The patients, who were at least 80 years old and had a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher, were judged inappropriate candidates for OAC at dosages approved for stroke prevention.

The mean age of the patients was 86.6, more than a decade older than patients “in the previous landmark clinical trials of direct oral anticoagulants,” and were 5-10 years older than the general AFib population, reported Dr. Okumura and colleagues.

Their mean weight was 52 kg, and mean creatinine clearance was 36.3 mL/min; 41% were classified as frail according to validated assessment tools.

Of the 303 patients who did not complete the trial, 158 voluntarily withdrew for various reasons. The withdrawal rate was similar in the two treatment arms. Outcomes were analyzed by intention to treat, the report noted.

The annualized rate of stroke or systemic embolism, the primary efficacy endpoint, was 2.3% for those who received edoxaban and 6.7% for the control group. Corresponding rates for the primary safety endpoint, major bleeding as determined by International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria, were 3.3% and 1.8%, respectively.

“The question is, can the Food and Drug Administration act on this information? I doubt it can. What will be needed is to reproduce the study in a U.S. population to see if it holds,” Dr. Singer proposed.

“Edoxaban isn’t used much in the U.S. This could heighten interest. And who knows, there may be a gold rush,” he said, if the strategy were to pan out for the other DOACs, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and dabigatran (Pradaxa).

ELDERCARE-AF was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, from which Dr. Okumura reported receiving grants and personal fees; he also disclosed personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, and Bayer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

suggests a randomized trial conducted in Japan.

Many of the study’s 984 mostly octogenarian patients were objectively frail with poor renal function, low body weight, a history of serious bleeding, or other conditions that made them poor candidates for regular-dose oral anticoagulation. Yet those who took the factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) at the off-label dosage of 15 mg once daily showed a two-thirds drop in risk for stroke or systemic embolism (P < .001), compared with patients who received placebo. There were no fatal bleeds and virtually no intracranial hemorrhages.

For such high-risk patients with nonvalvular AFib who otherwise would not be given an OAC, edoxaban 15 mg “can be an acceptable treatment option in decreasing the risk of devastating stroke”; however, “it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, so care should be given in every patient,” said Ken Okumura, MD, PhD. Indeed, the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding tripled among the patients who received edoxaban, compared with those given placebo, at about 2.3% per year versus 0.8% per year.

Although their 87% increased risk for major bleeding did not reach significance, it hit close, with a P value of .09 in the trial, called Edoxaban Low-Dose for Elder Care Atrial Fibrillation Patients (ELDERCARE-AF).

Dr. Okumura, of Saiseikai Kumamoto (Japan) Hospital, presented the study August 30 during the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He is lead author of an article describing the study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many patients with AFib suffer strokes if they are not given oral anticoagulation because of “fear of major bleeding caused by standard OAC therapy,” Dr. Okumura noted. Others are inappropriately administered antiplatelets or anticoagulants at conventional dosages. “There is no standard of practice in Japan for patients like those in the present trial,” Dr. Okumura said. “However, I believe the present study opens a new possible path of thromboprophylaxis in such high-risk patients.”

Even with its relatively few bleeding events, ELDERCARE-AF “does suggest that the risk of the worst types of bleeds is not that high,” said Daniel E. Singer, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Gastrointestinal bleeding is annoying, and it will probably stop people from taking their edoxaban, but for the most part it doesn’t kill people.”

Moreover, he added, the trial suggests that low-dose edoxaban, in exchange for a steep reduction in thromboembolic risk, “doesn’t add to your risk of intracranial hemorrhage!”

ELDERCARE-AF may give practitioners “yet another reason to rethink” whether a low-dose DOAC such as edoxaban 15 mg/day may well be a good approach for such patients with AFib who are not receiving standard-dose OAC because of a perceived high risk for serious bleeding, said Dr. Singer, who was not involved in the study.

The trial randomly and evenly assigned 984 patients with AF in Japan to take either edoxaban 15 mg/day or placebo. The patients, who were at least 80 years old and had a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher, were judged inappropriate candidates for OAC at dosages approved for stroke prevention.

The mean age of the patients was 86.6, more than a decade older than patients “in the previous landmark clinical trials of direct oral anticoagulants,” and were 5-10 years older than the general AFib population, reported Dr. Okumura and colleagues.

Their mean weight was 52 kg, and mean creatinine clearance was 36.3 mL/min; 41% were classified as frail according to validated assessment tools.

Of the 303 patients who did not complete the trial, 158 voluntarily withdrew for various reasons. The withdrawal rate was similar in the two treatment arms. Outcomes were analyzed by intention to treat, the report noted.

The annualized rate of stroke or systemic embolism, the primary efficacy endpoint, was 2.3% for those who received edoxaban and 6.7% for the control group. Corresponding rates for the primary safety endpoint, major bleeding as determined by International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria, were 3.3% and 1.8%, respectively.

“The question is, can the Food and Drug Administration act on this information? I doubt it can. What will be needed is to reproduce the study in a U.S. population to see if it holds,” Dr. Singer proposed.

“Edoxaban isn’t used much in the U.S. This could heighten interest. And who knows, there may be a gold rush,” he said, if the strategy were to pan out for the other DOACs, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and dabigatran (Pradaxa).

ELDERCARE-AF was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, from which Dr. Okumura reported receiving grants and personal fees; he also disclosed personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, and Bayer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

suggests a randomized trial conducted in Japan.

Many of the study’s 984 mostly octogenarian patients were objectively frail with poor renal function, low body weight, a history of serious bleeding, or other conditions that made them poor candidates for regular-dose oral anticoagulation. Yet those who took the factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) at the off-label dosage of 15 mg once daily showed a two-thirds drop in risk for stroke or systemic embolism (P < .001), compared with patients who received placebo. There were no fatal bleeds and virtually no intracranial hemorrhages.

For such high-risk patients with nonvalvular AFib who otherwise would not be given an OAC, edoxaban 15 mg “can be an acceptable treatment option in decreasing the risk of devastating stroke”; however, “it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, so care should be given in every patient,” said Ken Okumura, MD, PhD. Indeed, the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding tripled among the patients who received edoxaban, compared with those given placebo, at about 2.3% per year versus 0.8% per year.

Although their 87% increased risk for major bleeding did not reach significance, it hit close, with a P value of .09 in the trial, called Edoxaban Low-Dose for Elder Care Atrial Fibrillation Patients (ELDERCARE-AF).

Dr. Okumura, of Saiseikai Kumamoto (Japan) Hospital, presented the study August 30 during the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He is lead author of an article describing the study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many patients with AFib suffer strokes if they are not given oral anticoagulation because of “fear of major bleeding caused by standard OAC therapy,” Dr. Okumura noted. Others are inappropriately administered antiplatelets or anticoagulants at conventional dosages. “There is no standard of practice in Japan for patients like those in the present trial,” Dr. Okumura said. “However, I believe the present study opens a new possible path of thromboprophylaxis in such high-risk patients.”

Even with its relatively few bleeding events, ELDERCARE-AF “does suggest that the risk of the worst types of bleeds is not that high,” said Daniel E. Singer, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Gastrointestinal bleeding is annoying, and it will probably stop people from taking their edoxaban, but for the most part it doesn’t kill people.”

Moreover, he added, the trial suggests that low-dose edoxaban, in exchange for a steep reduction in thromboembolic risk, “doesn’t add to your risk of intracranial hemorrhage!”

ELDERCARE-AF may give practitioners “yet another reason to rethink” whether a low-dose DOAC such as edoxaban 15 mg/day may well be a good approach for such patients with AFib who are not receiving standard-dose OAC because of a perceived high risk for serious bleeding, said Dr. Singer, who was not involved in the study.

The trial randomly and evenly assigned 984 patients with AF in Japan to take either edoxaban 15 mg/day or placebo. The patients, who were at least 80 years old and had a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher, were judged inappropriate candidates for OAC at dosages approved for stroke prevention.

The mean age of the patients was 86.6, more than a decade older than patients “in the previous landmark clinical trials of direct oral anticoagulants,” and were 5-10 years older than the general AFib population, reported Dr. Okumura and colleagues.

Their mean weight was 52 kg, and mean creatinine clearance was 36.3 mL/min; 41% were classified as frail according to validated assessment tools.

Of the 303 patients who did not complete the trial, 158 voluntarily withdrew for various reasons. The withdrawal rate was similar in the two treatment arms. Outcomes were analyzed by intention to treat, the report noted.

The annualized rate of stroke or systemic embolism, the primary efficacy endpoint, was 2.3% for those who received edoxaban and 6.7% for the control group. Corresponding rates for the primary safety endpoint, major bleeding as determined by International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria, were 3.3% and 1.8%, respectively.

“The question is, can the Food and Drug Administration act on this information? I doubt it can. What will be needed is to reproduce the study in a U.S. population to see if it holds,” Dr. Singer proposed.

“Edoxaban isn’t used much in the U.S. This could heighten interest. And who knows, there may be a gold rush,” he said, if the strategy were to pan out for the other DOACs, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and dabigatran (Pradaxa).

ELDERCARE-AF was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, from which Dr. Okumura reported receiving grants and personal fees; he also disclosed personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, and Bayer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2020