User login

Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a clinical practice guideline aimed at decreasing opioid use in the treatment of chronic pain.1 It developed this guideline in response to the increasing problem of opioid abuse and opioid-related mortality in the United States.

The CDC notes that an estimated 1.9 million people abused or were dependent on prescription opioid pain medication in 2013.1 Between 1999 and 2014, more than 165,000 people in the United States died from an overdose of opioid pain medication, with that rate increasing markedly in the past decade.1 In 2011, an estimated 420,000 emergency department visits were related to the abuse of narcotic pain relievers.2

While the problem of increasing opioid-related abuse and deaths has been apparent for some time, effective interventions have been elusive. Evidence remains sparse on the benefits and harms of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain, except for those at the end of life. Evidence has been insufficient to determine long-term benefits of opioid therapy vs no opioid therapy, although the potential for harms from high doses of opioids are documented. There is not much evidence comparing nonpharmacologic and non-opioid pharmacologic treatments with long-term opioid therapy.

This lack of an evidence base is reflected in the CDC guideline. Of the guideline’s 12 recommendations, not one has high-level supporting evidence and only one has even moderate-level evidence behind it. Four recommendations are supported by low-level evidence, and 7 by very-low-level evidence. Yet 11 of the 12 are given an A recommendation, meaning that the guideline panel feels that most patients should receive this course of action.

Methodology used to create the guideline

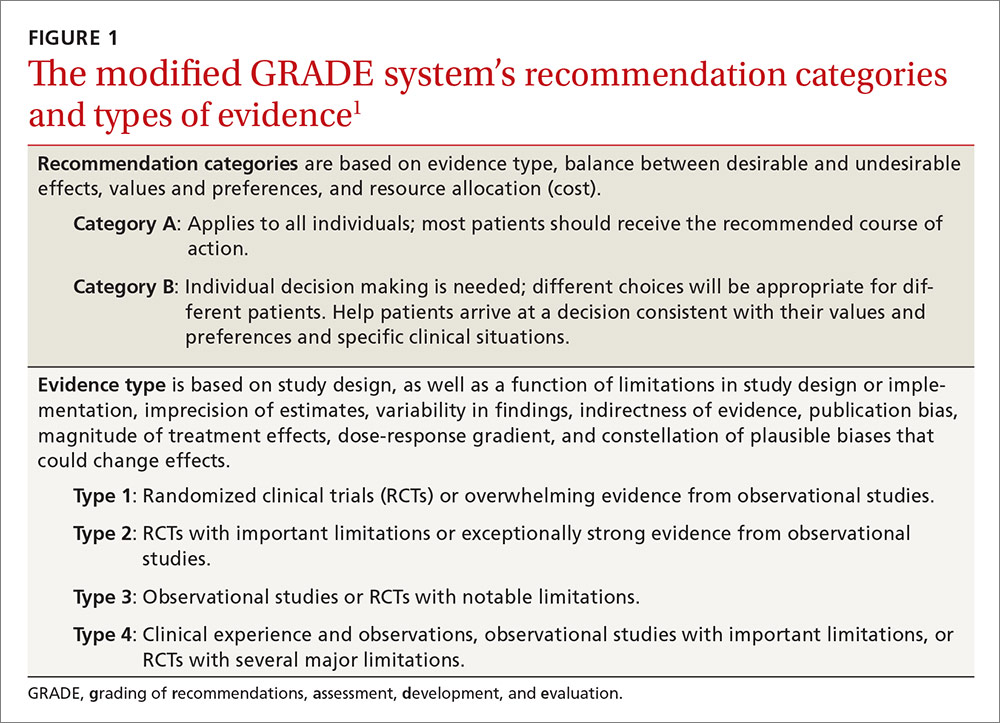

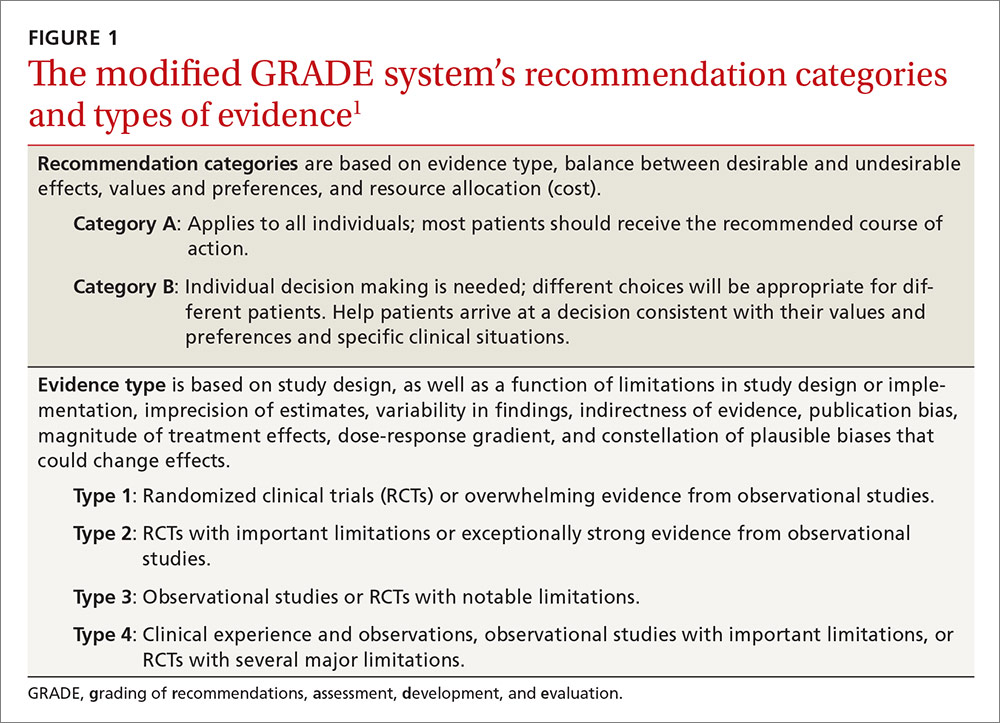

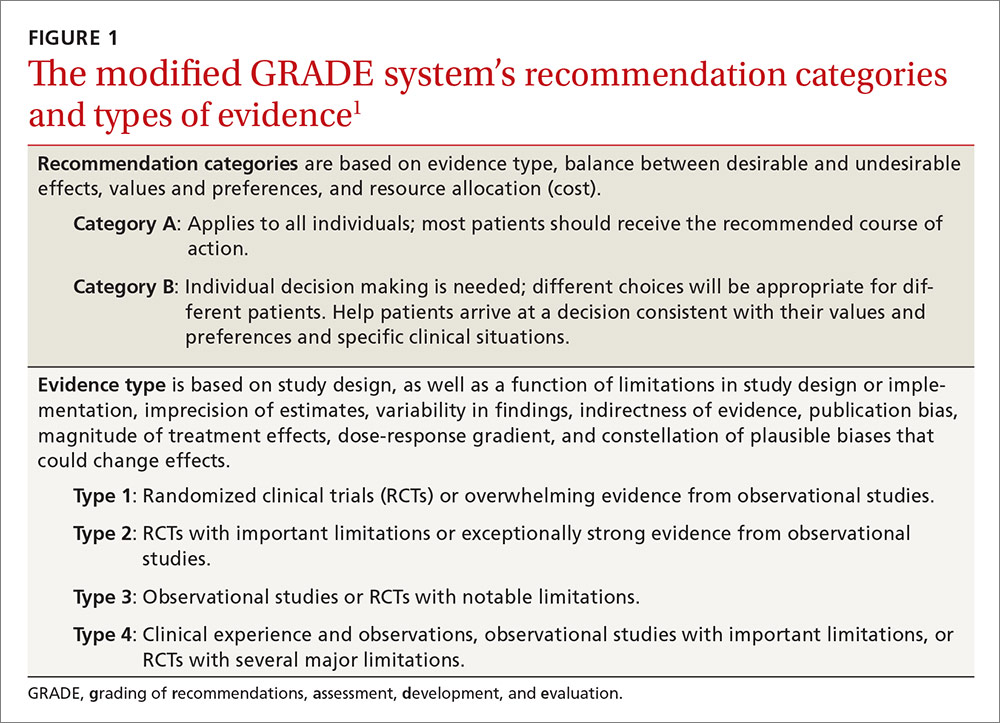

The guideline committee used a modified GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) to develop the guideline. It is the same system the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices adopted to assess and make recommendations on vaccines.3 The system’s classification of levels of evidence and recommendation categories are described in FIGURE 1.1

The committee started by assessing evidence with a report on the long-term effectiveness of opioids for chronic pain, produced by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality in 2014;4 it then augmented that report by performing an updated search for new evidence published since the report came out.5 The committee then conducted a “contextual evidence review”6 on the following 4 areas:

- the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic (cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise therapy, interventional treatments, multimodal pain treatment) and non-opioid pharmacologic treatments (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, anticonvulsants)

- the benefits and harms of opioid therapy

- clinician and patient values and preferences related to opioids and medication risks, benefits, and use

- resource allocation, including costs and economic analyses.

The guideline wording indicates that, for this contextual analysis, the committee used a rapid systematic review methodology, in part because of time constraints given the imperative to produce a guideline to address a pressing problem, and because of a recognition that evidence on the questions would be scant and not of high quality.1 The 12 recommendations are categorized under 3 main headings.

Determining when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Consider opioid therapy only if you anticipate that benefits for both pain and function will outweigh risks to the patient. If opioids are used, combine them as appropriate with nonpharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, establish treatment goals with the patient, including realistic goals for pain and function, and consider how therapy will be discontinued if the benefits do not outweigh the risks. Continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function that outweighs risks to patient safety. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

3. Before starting opioid therapy, and periodically during its course, discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for managing therapy. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

Opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) agents. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

5. When starting opioids, prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage; carefully reassess the evidence for individual benefits and risks when increasing the dosage to ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/d; and avoid increasing the dosage to ≥90 MME/d (or carefully justify such a decision, if made). (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

6. Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain. When opioids are used for acute pain, prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids at a quantity no greater than is needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or less will often be sufficient; more than 7 days will rarely be needed. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

7. In monitoring opioid therapy for chronic pain, reevaluate benefits and harms with patients within one to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy or escalating the dose. Also, evaluate the benefits and harms of continued therapy with patients every 3 months or more frequently. If the benefits of continued opioid therapy do not outweigh the harms, optimize other therapies and work with patients to taper opioids to lower dosages or to taper and discontinue them. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

Assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use

8. Before starting opioid therapy, and periodically during its continuation, evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms. Incorporate strategies into the management plan to mitigate risk; consider offering naloxone when factors are present that increase the risk for opioid overdose—eg, a history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, higher opioid dosages (≥50 MME/d), or concurrent benzodiazepine use. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

9. Review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions. Use data from the state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) to determine whether the patient is receiving opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. (State Web sites are available at http://www.pdmpassist.org/content/state-pdmp-websites.) Review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during its continuation, at least every 3 months and with each new prescription. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

10. Before prescribing opioids for chronic pain, use urine drug testing to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs, and consider urine drug testing at least annually. (Recommendation category: B; evidence type: 4)

11. Avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently whenever possible. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

12. For patients with opioid use disorder, offer or arrange for evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies). (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 2)

Aids for guideline implementation

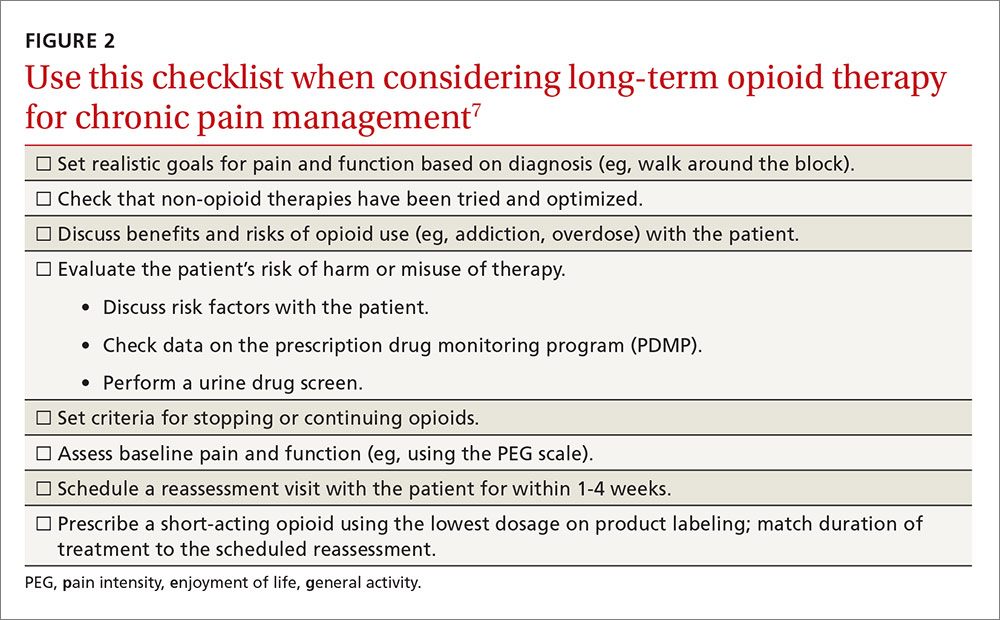

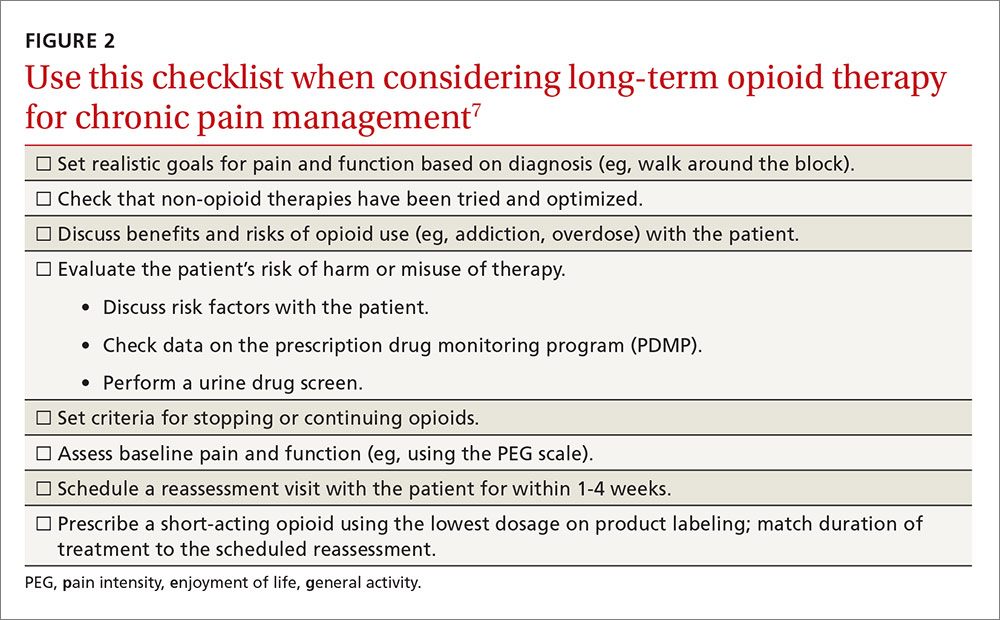

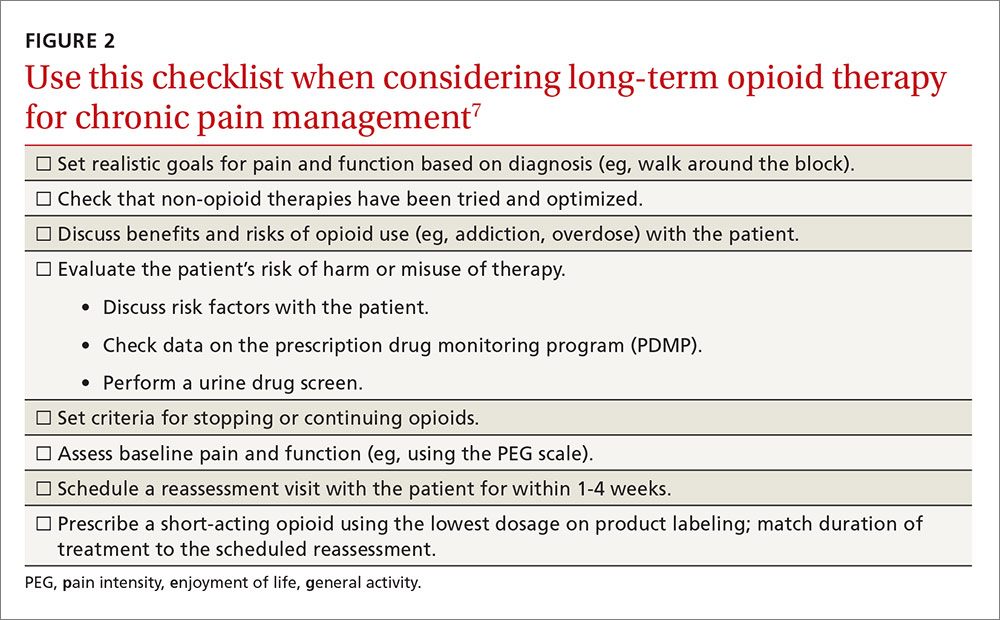

The CDC has produced materials to assist physicians in implementing this guideline, including checklists for prescribing or continuing opioids. The checklist for initiation of opioids is reproduced in FIGURE 2.7

The CDC is addressing a severe public health problem and doing so by using contemporary evidence-based methodology and guideline development processes. The lack of high-quality evidence on the topic and the use of a less-than-optimal evidence review process for some key questions may hamper this effort. However, given the prominence of the CDC, this clinical guideline will likely be considered the standard of care for family physicians.

1. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–49. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm. Accessed October 17, 20

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. 20

3. Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, et al; for the ACIP Evidence Based Recommendations Work Group (EBRWG). Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine. 2011;29:9171-9176.

4. Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 218. AHRQ Publication No. 14-E005-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/557/1971/chronic-pain-opioid-treatment-report-141205.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical evidence review for the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain-United States, 2016. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38026. Accessed October 17, 2016.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Contextual evidence review for the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – United States, 2016. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38027. Accessed October 17, 2016.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38025. Accessed October 17, 2016.

Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a clinical practice guideline aimed at decreasing opioid use in the treatment of chronic pain.1 It developed this guideline in response to the increasing problem of opioid abuse and opioid-related mortality in the United States.

The CDC notes that an estimated 1.9 million people abused or were dependent on prescription opioid pain medication in 2013.1 Between 1999 and 2014, more than 165,000 people in the United States died from an overdose of opioid pain medication, with that rate increasing markedly in the past decade.1 In 2011, an estimated 420,000 emergency department visits were related to the abuse of narcotic pain relievers.2

While the problem of increasing opioid-related abuse and deaths has been apparent for some time, effective interventions have been elusive. Evidence remains sparse on the benefits and harms of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain, except for those at the end of life. Evidence has been insufficient to determine long-term benefits of opioid therapy vs no opioid therapy, although the potential for harms from high doses of opioids are documented. There is not much evidence comparing nonpharmacologic and non-opioid pharmacologic treatments with long-term opioid therapy.

This lack of an evidence base is reflected in the CDC guideline. Of the guideline’s 12 recommendations, not one has high-level supporting evidence and only one has even moderate-level evidence behind it. Four recommendations are supported by low-level evidence, and 7 by very-low-level evidence. Yet 11 of the 12 are given an A recommendation, meaning that the guideline panel feels that most patients should receive this course of action.

Methodology used to create the guideline

The guideline committee used a modified GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) to develop the guideline. It is the same system the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices adopted to assess and make recommendations on vaccines.3 The system’s classification of levels of evidence and recommendation categories are described in FIGURE 1.1

The committee started by assessing evidence with a report on the long-term effectiveness of opioids for chronic pain, produced by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality in 2014;4 it then augmented that report by performing an updated search for new evidence published since the report came out.5 The committee then conducted a “contextual evidence review”6 on the following 4 areas:

- the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic (cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise therapy, interventional treatments, multimodal pain treatment) and non-opioid pharmacologic treatments (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, anticonvulsants)

- the benefits and harms of opioid therapy

- clinician and patient values and preferences related to opioids and medication risks, benefits, and use

- resource allocation, including costs and economic analyses.

The guideline wording indicates that, for this contextual analysis, the committee used a rapid systematic review methodology, in part because of time constraints given the imperative to produce a guideline to address a pressing problem, and because of a recognition that evidence on the questions would be scant and not of high quality.1 The 12 recommendations are categorized under 3 main headings.

Determining when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Consider opioid therapy only if you anticipate that benefits for both pain and function will outweigh risks to the patient. If opioids are used, combine them as appropriate with nonpharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, establish treatment goals with the patient, including realistic goals for pain and function, and consider how therapy will be discontinued if the benefits do not outweigh the risks. Continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function that outweighs risks to patient safety. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

3. Before starting opioid therapy, and periodically during its course, discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for managing therapy. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

Opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) agents. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

5. When starting opioids, prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage; carefully reassess the evidence for individual benefits and risks when increasing the dosage to ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/d; and avoid increasing the dosage to ≥90 MME/d (or carefully justify such a decision, if made). (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

6. Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain. When opioids are used for acute pain, prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids at a quantity no greater than is needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or less will often be sufficient; more than 7 days will rarely be needed. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

7. In monitoring opioid therapy for chronic pain, reevaluate benefits and harms with patients within one to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy or escalating the dose. Also, evaluate the benefits and harms of continued therapy with patients every 3 months or more frequently. If the benefits of continued opioid therapy do not outweigh the harms, optimize other therapies and work with patients to taper opioids to lower dosages or to taper and discontinue them. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

Assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use

8. Before starting opioid therapy, and periodically during its continuation, evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms. Incorporate strategies into the management plan to mitigate risk; consider offering naloxone when factors are present that increase the risk for opioid overdose—eg, a history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, higher opioid dosages (≥50 MME/d), or concurrent benzodiazepine use. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

9. Review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions. Use data from the state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) to determine whether the patient is receiving opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. (State Web sites are available at http://www.pdmpassist.org/content/state-pdmp-websites.) Review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during its continuation, at least every 3 months and with each new prescription. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

10. Before prescribing opioids for chronic pain, use urine drug testing to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs, and consider urine drug testing at least annually. (Recommendation category: B; evidence type: 4)

11. Avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently whenever possible. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

12. For patients with opioid use disorder, offer or arrange for evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies). (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 2)

Aids for guideline implementation

The CDC has produced materials to assist physicians in implementing this guideline, including checklists for prescribing or continuing opioids. The checklist for initiation of opioids is reproduced in FIGURE 2.7

The CDC is addressing a severe public health problem and doing so by using contemporary evidence-based methodology and guideline development processes. The lack of high-quality evidence on the topic and the use of a less-than-optimal evidence review process for some key questions may hamper this effort. However, given the prominence of the CDC, this clinical guideline will likely be considered the standard of care for family physicians.

Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a clinical practice guideline aimed at decreasing opioid use in the treatment of chronic pain.1 It developed this guideline in response to the increasing problem of opioid abuse and opioid-related mortality in the United States.

The CDC notes that an estimated 1.9 million people abused or were dependent on prescription opioid pain medication in 2013.1 Between 1999 and 2014, more than 165,000 people in the United States died from an overdose of opioid pain medication, with that rate increasing markedly in the past decade.1 In 2011, an estimated 420,000 emergency department visits were related to the abuse of narcotic pain relievers.2

While the problem of increasing opioid-related abuse and deaths has been apparent for some time, effective interventions have been elusive. Evidence remains sparse on the benefits and harms of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain, except for those at the end of life. Evidence has been insufficient to determine long-term benefits of opioid therapy vs no opioid therapy, although the potential for harms from high doses of opioids are documented. There is not much evidence comparing nonpharmacologic and non-opioid pharmacologic treatments with long-term opioid therapy.

This lack of an evidence base is reflected in the CDC guideline. Of the guideline’s 12 recommendations, not one has high-level supporting evidence and only one has even moderate-level evidence behind it. Four recommendations are supported by low-level evidence, and 7 by very-low-level evidence. Yet 11 of the 12 are given an A recommendation, meaning that the guideline panel feels that most patients should receive this course of action.

Methodology used to create the guideline

The guideline committee used a modified GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) to develop the guideline. It is the same system the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices adopted to assess and make recommendations on vaccines.3 The system’s classification of levels of evidence and recommendation categories are described in FIGURE 1.1

The committee started by assessing evidence with a report on the long-term effectiveness of opioids for chronic pain, produced by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality in 2014;4 it then augmented that report by performing an updated search for new evidence published since the report came out.5 The committee then conducted a “contextual evidence review”6 on the following 4 areas:

- the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic (cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise therapy, interventional treatments, multimodal pain treatment) and non-opioid pharmacologic treatments (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, anticonvulsants)

- the benefits and harms of opioid therapy

- clinician and patient values and preferences related to opioids and medication risks, benefits, and use

- resource allocation, including costs and economic analyses.

The guideline wording indicates that, for this contextual analysis, the committee used a rapid systematic review methodology, in part because of time constraints given the imperative to produce a guideline to address a pressing problem, and because of a recognition that evidence on the questions would be scant and not of high quality.1 The 12 recommendations are categorized under 3 main headings.

Determining when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Consider opioid therapy only if you anticipate that benefits for both pain and function will outweigh risks to the patient. If opioids are used, combine them as appropriate with nonpharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, establish treatment goals with the patient, including realistic goals for pain and function, and consider how therapy will be discontinued if the benefits do not outweigh the risks. Continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function that outweighs risks to patient safety. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

3. Before starting opioid therapy, and periodically during its course, discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for managing therapy. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

Opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) agents. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

5. When starting opioids, prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage; carefully reassess the evidence for individual benefits and risks when increasing the dosage to ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/d; and avoid increasing the dosage to ≥90 MME/d (or carefully justify such a decision, if made). (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

6. Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain. When opioids are used for acute pain, prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids at a quantity no greater than is needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or less will often be sufficient; more than 7 days will rarely be needed. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

7. In monitoring opioid therapy for chronic pain, reevaluate benefits and harms with patients within one to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy or escalating the dose. Also, evaluate the benefits and harms of continued therapy with patients every 3 months or more frequently. If the benefits of continued opioid therapy do not outweigh the harms, optimize other therapies and work with patients to taper opioids to lower dosages or to taper and discontinue them. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

Assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use

8. Before starting opioid therapy, and periodically during its continuation, evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms. Incorporate strategies into the management plan to mitigate risk; consider offering naloxone when factors are present that increase the risk for opioid overdose—eg, a history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, higher opioid dosages (≥50 MME/d), or concurrent benzodiazepine use. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

9. Review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions. Use data from the state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) to determine whether the patient is receiving opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. (State Web sites are available at http://www.pdmpassist.org/content/state-pdmp-websites.) Review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during its continuation, at least every 3 months and with each new prescription. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 4)

10. Before prescribing opioids for chronic pain, use urine drug testing to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs, and consider urine drug testing at least annually. (Recommendation category: B; evidence type: 4)

11. Avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently whenever possible. (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 3)

12. For patients with opioid use disorder, offer or arrange for evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies). (Recommendation category: A; evidence type: 2)

Aids for guideline implementation

The CDC has produced materials to assist physicians in implementing this guideline, including checklists for prescribing or continuing opioids. The checklist for initiation of opioids is reproduced in FIGURE 2.7

The CDC is addressing a severe public health problem and doing so by using contemporary evidence-based methodology and guideline development processes. The lack of high-quality evidence on the topic and the use of a less-than-optimal evidence review process for some key questions may hamper this effort. However, given the prominence of the CDC, this clinical guideline will likely be considered the standard of care for family physicians.

1. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–49. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm. Accessed October 17, 20

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. 20

3. Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, et al; for the ACIP Evidence Based Recommendations Work Group (EBRWG). Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine. 2011;29:9171-9176.

4. Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 218. AHRQ Publication No. 14-E005-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/557/1971/chronic-pain-opioid-treatment-report-141205.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical evidence review for the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain-United States, 2016. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38026. Accessed October 17, 2016.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Contextual evidence review for the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – United States, 2016. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38027. Accessed October 17, 2016.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38025. Accessed October 17, 2016.

1. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–49. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm. Accessed October 17, 20

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. 20

3. Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, et al; for the ACIP Evidence Based Recommendations Work Group (EBRWG). Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine. 2011;29:9171-9176.

4. Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 218. AHRQ Publication No. 14-E005-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/557/1971/chronic-pain-opioid-treatment-report-141205.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical evidence review for the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain-United States, 2016. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38026. Accessed October 17, 2016.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Contextual evidence review for the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – United States, 2016. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38027. Accessed October 17, 2016.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38025. Accessed October 17, 2016.