User login

An 18-year-old woman, pregnant for the third time, presented to the emergency department with constant vaginal bleeding and intermittent cramping for the past 3 weeks. Her last menstrual period was 14 weeks and 2 days ago. In her previous two pregnancies, she had given birth to one living child and had had one miscarriage.

Physical examination suggested that her uterus was bigger than expected for the gestational age, measuring 23 cm from the symphysis pubis to the uterine fundus. Ultrasonography in the obstetrics service revealed a “snowstorm” appearance strongly suggestive of molar pregnancy. Her level of beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) was greater than 1,125,000 mIU/mL (reference range for 14 weeks of pregnancy 18,300–137,000). Dilation and curettage was performed, and pathologic study confirmed molar pregnancy.

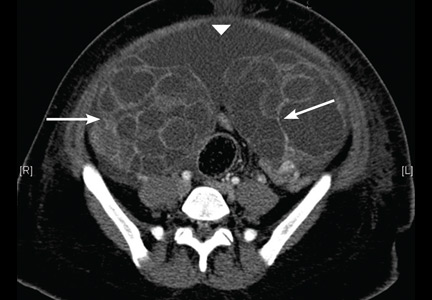

On the 6th day after the procedure, she returned to the emergency department with progressive abdominal pain, distention, and nausea. Her blood urea nitrogen level was 8 mg/dL (reference range 5–20 mg/dL) and her serum creatinine level was 0.5 mg/dL (0.5–0.9). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated an enlarged and bulky uterus with heterogeneous enhancement. The ovaries were greatly enlarged with multiple cysts, and massive ascites was noted in the abdomen (Figures 1 and 2). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS).

OVARIAN HYPERSTIMULATION SYNDROME

OHSS is enlargement of the ovaries associated with fluid shifts secondary to ovulation induction therapy with clomiphene citrate or hCG.1 In its mild form, it is a common complication, seen in 5% to 10% of patients undergoing ovulation induction; the moderate form is reported in 2% to 4% of patients undergoing ovulation induction, and the severe form in 0.1% to 0.5%.2 It may also occur spontaneously after pregnancy or with any condition that leads to a rise in hCG levels.

Factors associated with a high risk of developing OHSS include young age, low body weight, polycystic ovary syndrome, a high serum estradiol level, and a history of OHSS.3,4

In our patient, OHSS was secondary to molar pregnancy and markedly elevated hCG levels. Hydatidiform mole or molar pregnancy is a cystic swelling of the chorionic villi and proliferation of the trophoblastic epithelium. Elevated circulating hCG is thought to lead to ovarian enlargement and multiple cysts; this stimulates the ovaries to secrete vasoactive substances, increasing vascular permeability, leading to fluid shifts and the accumulation of extravascular fluid, resulting in renal failure, hypovolemic shock, ascites, and pleural and pericardial effusions.5 This acute shift produces hypovolemia, which may result in multiple organ failure, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 45%), thrombosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation from the increased viscosity of the blood.

GRADING OF OHSS IS BASED ON SYMPTOMS, TEST RESULTS, IMAGING

The severity of OHSS is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, with further grading as follows5,6:

Mild OHSS

- Grade 1: abdominal distention and discomfort.

- Grade 2: features of grade 1, plus nausea and vomiting, with or without diarrhea, and ovarian size of 5 to 12 cm.

Moderate OHSS

- Grade 3: mild OHSS with imaging evidence of ascites.

Severe OHSS

- Grade 4: moderate OHSS plus clinical evidence of ascites, with or without hydrothorax.

- Grade 5: all of the above plus hypovolemia, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 45%), coagulation abnormalities, and oliguria.

- Grade 6: all the features of grades 1 to 4 plus hypovolemia, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 55%), anuria, renal failure, venous thrombosis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. This can be life-threatening and may require hospitalization.

TREATMENT

Treatment is generally conservative and includes management of ascites and pleural effusion and supportive care.

Mild OHSS can be treated on an outpatient basis with bed rest, oral analgesics, limited oral intake, and avoidance of vaginal intercourse, and usually resolves in 10 to 14 days. Moderate and severe OHSS require bed rest and aggressive fluid resuscitation. OHSS in patients with renal failure, relentless hemoconcentration, or thrombovascular accident can be life-threatening and may require intensive-care monitoring.

Paracentesis may be performed if tension ascites and oliguria or anuria develop.2 Prophylactic anticoagulation with warfarin, heparin, or low-molecular-weight heparin is indicated in women with a high tendency for thrombotic events who develop moderate to severe OHSS.3,4

Surgical intervention may be necessary in patients with ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, or ruptured ovarian cyst.

Our patient was treated conservatively with supportive care and experienced a full recovery.

- Arora R, Merhi ZO, Khulpateea N, Roth D, Minkoff H. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome after a molar pregnancy evacuation. Fertil Steril 2008; 90:1197.e5–e7.

- Fiedler K, Ezcurra D. Predicting and preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): the need for individualized not standardized treatment. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012; 10:32.

- Mor YS, Schenker JG. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and thrombotic events. Am J Reprod Immunol 2014; 72:541–548.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2008; 90(suppl):S188–S193.

- Whelan JG 3rd, Vlahos NF. The ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2000; 73:883–896.

- Golan A, Weissman A. Symposium: update on prediction and management of OHSS. A modern classification of OHSS. Reprod Biomed Online 2009; 19:28–32.

An 18-year-old woman, pregnant for the third time, presented to the emergency department with constant vaginal bleeding and intermittent cramping for the past 3 weeks. Her last menstrual period was 14 weeks and 2 days ago. In her previous two pregnancies, she had given birth to one living child and had had one miscarriage.

Physical examination suggested that her uterus was bigger than expected for the gestational age, measuring 23 cm from the symphysis pubis to the uterine fundus. Ultrasonography in the obstetrics service revealed a “snowstorm” appearance strongly suggestive of molar pregnancy. Her level of beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) was greater than 1,125,000 mIU/mL (reference range for 14 weeks of pregnancy 18,300–137,000). Dilation and curettage was performed, and pathologic study confirmed molar pregnancy.

On the 6th day after the procedure, she returned to the emergency department with progressive abdominal pain, distention, and nausea. Her blood urea nitrogen level was 8 mg/dL (reference range 5–20 mg/dL) and her serum creatinine level was 0.5 mg/dL (0.5–0.9). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated an enlarged and bulky uterus with heterogeneous enhancement. The ovaries were greatly enlarged with multiple cysts, and massive ascites was noted in the abdomen (Figures 1 and 2). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS).

OVARIAN HYPERSTIMULATION SYNDROME

OHSS is enlargement of the ovaries associated with fluid shifts secondary to ovulation induction therapy with clomiphene citrate or hCG.1 In its mild form, it is a common complication, seen in 5% to 10% of patients undergoing ovulation induction; the moderate form is reported in 2% to 4% of patients undergoing ovulation induction, and the severe form in 0.1% to 0.5%.2 It may also occur spontaneously after pregnancy or with any condition that leads to a rise in hCG levels.

Factors associated with a high risk of developing OHSS include young age, low body weight, polycystic ovary syndrome, a high serum estradiol level, and a history of OHSS.3,4

In our patient, OHSS was secondary to molar pregnancy and markedly elevated hCG levels. Hydatidiform mole or molar pregnancy is a cystic swelling of the chorionic villi and proliferation of the trophoblastic epithelium. Elevated circulating hCG is thought to lead to ovarian enlargement and multiple cysts; this stimulates the ovaries to secrete vasoactive substances, increasing vascular permeability, leading to fluid shifts and the accumulation of extravascular fluid, resulting in renal failure, hypovolemic shock, ascites, and pleural and pericardial effusions.5 This acute shift produces hypovolemia, which may result in multiple organ failure, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 45%), thrombosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation from the increased viscosity of the blood.

GRADING OF OHSS IS BASED ON SYMPTOMS, TEST RESULTS, IMAGING

The severity of OHSS is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, with further grading as follows5,6:

Mild OHSS

- Grade 1: abdominal distention and discomfort.

- Grade 2: features of grade 1, plus nausea and vomiting, with or without diarrhea, and ovarian size of 5 to 12 cm.

Moderate OHSS

- Grade 3: mild OHSS with imaging evidence of ascites.

Severe OHSS

- Grade 4: moderate OHSS plus clinical evidence of ascites, with or without hydrothorax.

- Grade 5: all of the above plus hypovolemia, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 45%), coagulation abnormalities, and oliguria.

- Grade 6: all the features of grades 1 to 4 plus hypovolemia, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 55%), anuria, renal failure, venous thrombosis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. This can be life-threatening and may require hospitalization.

TREATMENT

Treatment is generally conservative and includes management of ascites and pleural effusion and supportive care.

Mild OHSS can be treated on an outpatient basis with bed rest, oral analgesics, limited oral intake, and avoidance of vaginal intercourse, and usually resolves in 10 to 14 days. Moderate and severe OHSS require bed rest and aggressive fluid resuscitation. OHSS in patients with renal failure, relentless hemoconcentration, or thrombovascular accident can be life-threatening and may require intensive-care monitoring.

Paracentesis may be performed if tension ascites and oliguria or anuria develop.2 Prophylactic anticoagulation with warfarin, heparin, or low-molecular-weight heparin is indicated in women with a high tendency for thrombotic events who develop moderate to severe OHSS.3,4

Surgical intervention may be necessary in patients with ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, or ruptured ovarian cyst.

Our patient was treated conservatively with supportive care and experienced a full recovery.

An 18-year-old woman, pregnant for the third time, presented to the emergency department with constant vaginal bleeding and intermittent cramping for the past 3 weeks. Her last menstrual period was 14 weeks and 2 days ago. In her previous two pregnancies, she had given birth to one living child and had had one miscarriage.

Physical examination suggested that her uterus was bigger than expected for the gestational age, measuring 23 cm from the symphysis pubis to the uterine fundus. Ultrasonography in the obstetrics service revealed a “snowstorm” appearance strongly suggestive of molar pregnancy. Her level of beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) was greater than 1,125,000 mIU/mL (reference range for 14 weeks of pregnancy 18,300–137,000). Dilation and curettage was performed, and pathologic study confirmed molar pregnancy.

On the 6th day after the procedure, she returned to the emergency department with progressive abdominal pain, distention, and nausea. Her blood urea nitrogen level was 8 mg/dL (reference range 5–20 mg/dL) and her serum creatinine level was 0.5 mg/dL (0.5–0.9). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated an enlarged and bulky uterus with heterogeneous enhancement. The ovaries were greatly enlarged with multiple cysts, and massive ascites was noted in the abdomen (Figures 1 and 2). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS).

OVARIAN HYPERSTIMULATION SYNDROME

OHSS is enlargement of the ovaries associated with fluid shifts secondary to ovulation induction therapy with clomiphene citrate or hCG.1 In its mild form, it is a common complication, seen in 5% to 10% of patients undergoing ovulation induction; the moderate form is reported in 2% to 4% of patients undergoing ovulation induction, and the severe form in 0.1% to 0.5%.2 It may also occur spontaneously after pregnancy or with any condition that leads to a rise in hCG levels.

Factors associated with a high risk of developing OHSS include young age, low body weight, polycystic ovary syndrome, a high serum estradiol level, and a history of OHSS.3,4

In our patient, OHSS was secondary to molar pregnancy and markedly elevated hCG levels. Hydatidiform mole or molar pregnancy is a cystic swelling of the chorionic villi and proliferation of the trophoblastic epithelium. Elevated circulating hCG is thought to lead to ovarian enlargement and multiple cysts; this stimulates the ovaries to secrete vasoactive substances, increasing vascular permeability, leading to fluid shifts and the accumulation of extravascular fluid, resulting in renal failure, hypovolemic shock, ascites, and pleural and pericardial effusions.5 This acute shift produces hypovolemia, which may result in multiple organ failure, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 45%), thrombosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation from the increased viscosity of the blood.

GRADING OF OHSS IS BASED ON SYMPTOMS, TEST RESULTS, IMAGING

The severity of OHSS is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, with further grading as follows5,6:

Mild OHSS

- Grade 1: abdominal distention and discomfort.

- Grade 2: features of grade 1, plus nausea and vomiting, with or without diarrhea, and ovarian size of 5 to 12 cm.

Moderate OHSS

- Grade 3: mild OHSS with imaging evidence of ascites.

Severe OHSS

- Grade 4: moderate OHSS plus clinical evidence of ascites, with or without hydrothorax.

- Grade 5: all of the above plus hypovolemia, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 45%), coagulation abnormalities, and oliguria.

- Grade 6: all the features of grades 1 to 4 plus hypovolemia, hemoconcentration (hematocrit > 55%), anuria, renal failure, venous thrombosis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. This can be life-threatening and may require hospitalization.

TREATMENT

Treatment is generally conservative and includes management of ascites and pleural effusion and supportive care.

Mild OHSS can be treated on an outpatient basis with bed rest, oral analgesics, limited oral intake, and avoidance of vaginal intercourse, and usually resolves in 10 to 14 days. Moderate and severe OHSS require bed rest and aggressive fluid resuscitation. OHSS in patients with renal failure, relentless hemoconcentration, or thrombovascular accident can be life-threatening and may require intensive-care monitoring.

Paracentesis may be performed if tension ascites and oliguria or anuria develop.2 Prophylactic anticoagulation with warfarin, heparin, or low-molecular-weight heparin is indicated in women with a high tendency for thrombotic events who develop moderate to severe OHSS.3,4

Surgical intervention may be necessary in patients with ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, or ruptured ovarian cyst.

Our patient was treated conservatively with supportive care and experienced a full recovery.

- Arora R, Merhi ZO, Khulpateea N, Roth D, Minkoff H. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome after a molar pregnancy evacuation. Fertil Steril 2008; 90:1197.e5–e7.

- Fiedler K, Ezcurra D. Predicting and preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): the need for individualized not standardized treatment. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012; 10:32.

- Mor YS, Schenker JG. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and thrombotic events. Am J Reprod Immunol 2014; 72:541–548.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2008; 90(suppl):S188–S193.

- Whelan JG 3rd, Vlahos NF. The ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2000; 73:883–896.

- Golan A, Weissman A. Symposium: update on prediction and management of OHSS. A modern classification of OHSS. Reprod Biomed Online 2009; 19:28–32.

- Arora R, Merhi ZO, Khulpateea N, Roth D, Minkoff H. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome after a molar pregnancy evacuation. Fertil Steril 2008; 90:1197.e5–e7.

- Fiedler K, Ezcurra D. Predicting and preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): the need for individualized not standardized treatment. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012; 10:32.

- Mor YS, Schenker JG. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and thrombotic events. Am J Reprod Immunol 2014; 72:541–548.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2008; 90(suppl):S188–S193.

- Whelan JG 3rd, Vlahos NF. The ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2000; 73:883–896.

- Golan A, Weissman A. Symposium: update on prediction and management of OHSS. A modern classification of OHSS. Reprod Biomed Online 2009; 19:28–32.