User login

CASE Agitation and bizarre behavior

Ms. L, age 40, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status and bizarre behavior. Before arriving at the ED, she had experienced a severe headache and an episode of vomiting. At home she had been irritable and agitated, repetitively dressing and undressing, urinating outside the toilet, and opening and closing water faucets in the house. She also had stopped eating and drinking. Ms. L’s home medications consist of levothyroxine 100 mcg/d for hypothyroidism.

In the ED, Ms. L has severe psychomotor agitation. She is restless and displays purposeless repetitive movements with her hands. She is mostly mute, but does groan at times.

HISTORY Multiple trips to the ED

In addition to hypothyroidism, Ms. L has a history of migraines and asthma. Four days before presenting to the ED, she complained of a severe headache and generalized fatigue, with vomiting and nausea. Two days later, she presented to the ED at a different hospital and underwent a brain CT scan; the results were unremarkable. At that facility, a laboratory work-up—including complete blood count, urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, full liver function tests, amylase, lipase, bilirubin, thyroid function test, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin—was normal except for low thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (0.016 mIU/L). Ms. L was diagnosed with a severe migraine attack and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her endocrinologist.

Ms. L has no previous psychiatric history. Her family’s psychiatric history includes depression with psychotic features (mother), depression (maternal aunt), and generalized anxiety disorder (mother’s maternal aunt).

[polldaddy:11252938]

The authors’ observations

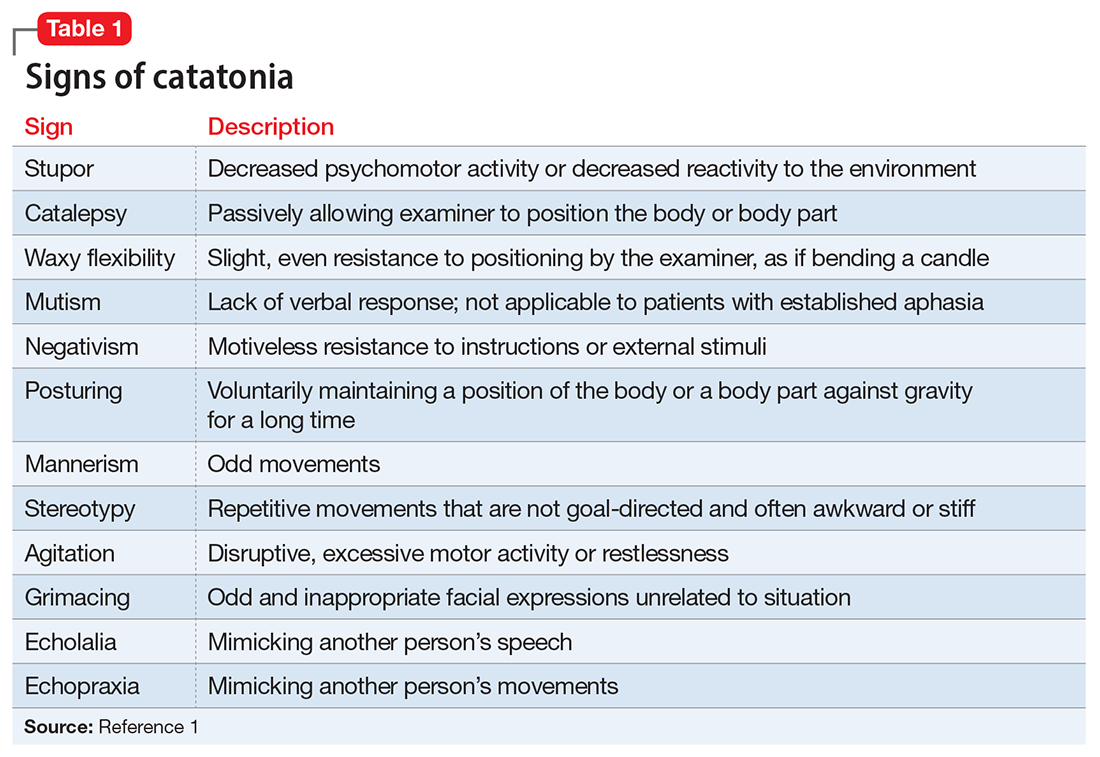

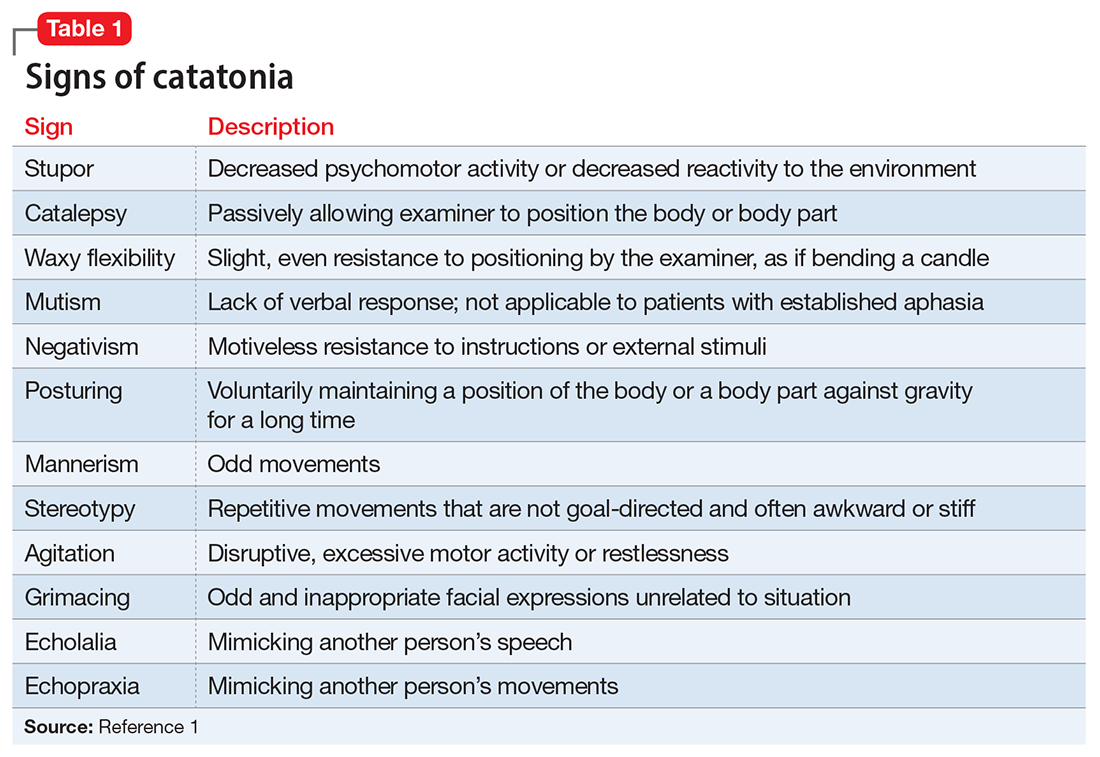

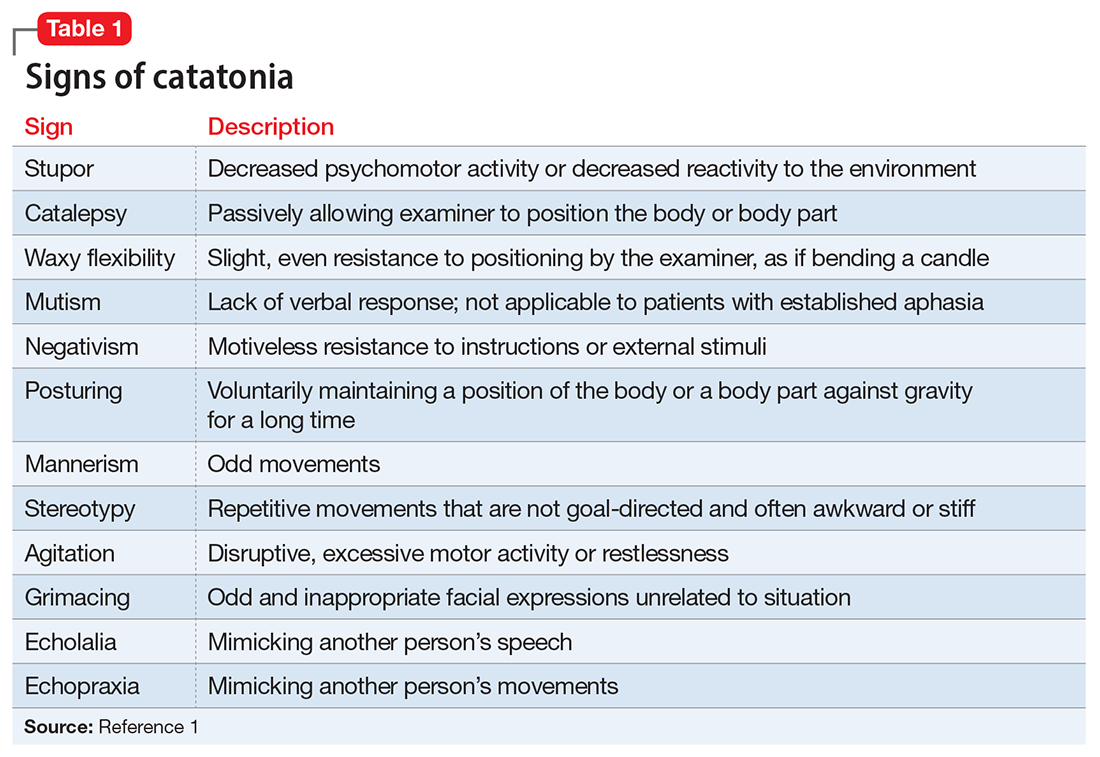

Catatonia is a behavioral syndrome with heterogeneous signs and symptoms. According to DSM-5, the diagnosis is considered when a patient presents with ≥3 of the 12 signs outlined in Table 1.1 It usually occurs in the context of an underlying psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or depression, or a medical disorder such as CNS infection or encephalopathy due to metabolic causes.1 Ms. L exhibited mutism, negativism, mannerism, stereotypy, and agitation and thus met the criteria for a catatonia diagnosis.

EVALUATION Unexpected finding on physical exam

In the ED, Ms. L is hemodynamically stable. Her blood pressure is 140/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; oxygen saturation is 98%; respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute; and temperature is 37.5° C. Results from a brain MRI and total body scan performed prior to admission are unremarkable.

Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric ward under the care of neurology for a psychiatry consultation. For approximately 24 hours, she receives IV diazepam 5 mg every 8 hours (due to the unavailability of lorazepam) for management of her catatonic symptoms, and olanzapine 10 mg every 8 hours orally as needed for agitation. Collateral history rules out a current mood episode or onset of psychosis in the weeks before she came to the ED. Diazepam improves Ms. L’s psychomotor agitation, which allows the primary team an opportunity to examine her.

Continue to: A physical exam reveals...

A physical exam reveals small vesicular lesions (1 to 2 cm in diameter) on an erythematous base on the left breast associated with an erythematous plaque with no evident vesicles on the left inner arm. The vesicular lesions display in a segmented pattern of dermatomal distribution.

[polldaddy:11252941]

The authors’ observations

Catatonic symptoms, coupled with psychomotor agitation in an immunocompetent middle-aged adult with a history of migraine headaches, strong family history of severe mental illness, and noncontributory findings on brain imaging, prompted a Psychiatry consultation and administration of psychotropic medications. A thorough physical exam revealing the small area of shingles and acute altered mental status prompted more aggressive investigations to explore the possibility of encephalitis.

Physicians should have a low index of suspicion for encephalitis (viral, bacterial, autoimmune, etc) and perform a lumbar puncture (LP) when necessary, despite the invasiveness of this test. A direct physical examination is often underutilized, notably in psychiatric patients, which can lead to the omission of important clinical information.2 Normal vital signs, blood workup, and MRI before admission are not sufficient to correctly guide diagnosis.

EVALUATION Additional lab results establish the diagnosis

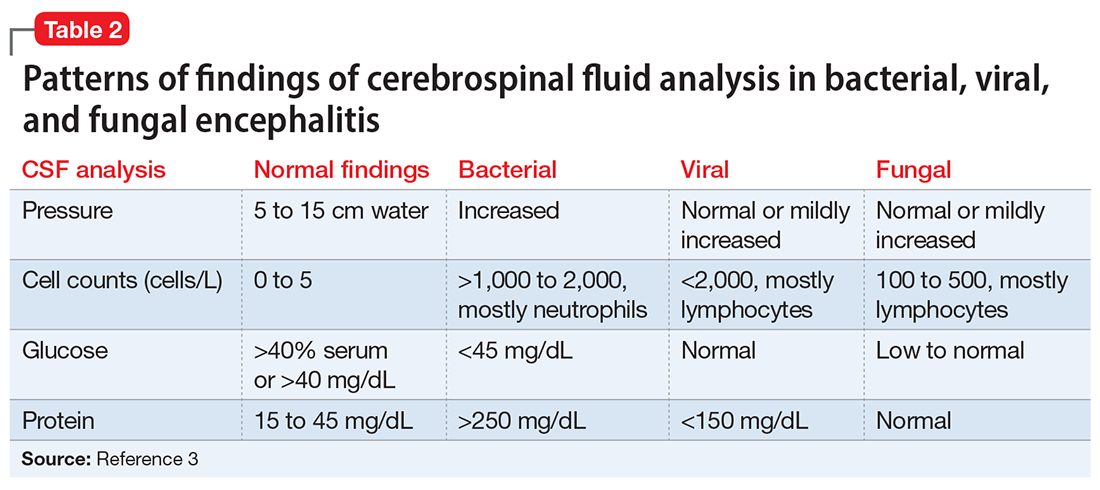

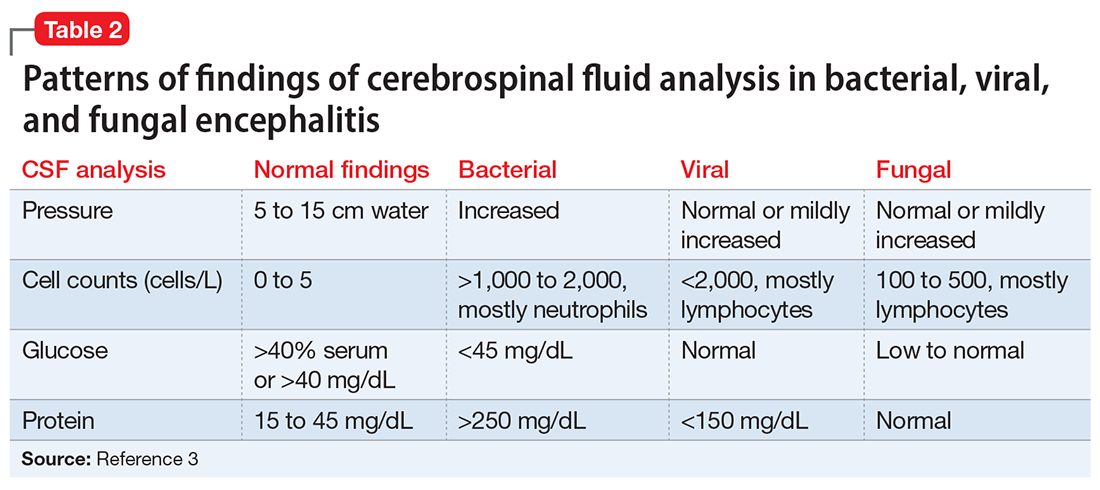

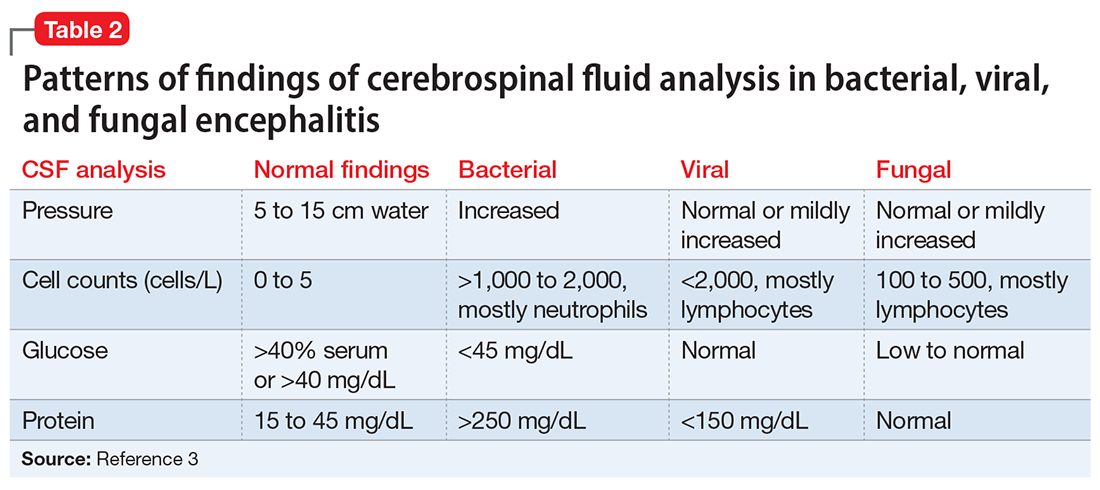

An LP reveals Ms. L’s protein levels are 44 mg/dL, her glucose levels are 85 mg/dL, red blood cell count is 4/µL, and white blood cell count is 200/µL with 92% lymphocytes and 1% neutrophils. Ms. L’s CSF analysis profile indicates a viral CNS infection (Table 23).

[polldaddy:11252943]

The authors’ observations

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) are human neurotropic alphaherpesviruses that cause lifelong infections in ganglia, and their reactivation can come in the form of encephalitis.4

Continue to: Ms. L's clinical presentation...

Ms. L’s clinical presentation most likely implicated VZV. Skin lesions of VZV may look exactly like HSV, with clustered vesicles on an erythematous base (Figure5). However, VZV rash tends to follow a dermatomal distribution (as in Ms. L’s case), which can help distinguish it from herpetic lesions.

Cases of VZV infection have been increasing worldwide. It is usually seen in older adults or those with compromised immunity.6 Significantly higher rates of VZV complications have been reported in such patients. A serious complication is VZV encephalitis, which is rare but possible, even in healthy individuals.6 VZV encephalitis can present with atypical psychiatric features. Ms. L exhibited several symptoms of VZV encephalitis, which include headache, fever, vomiting, altered level of consciousness, and seizures. An EEG also showed intermittent generalized slow waves in the range of theta commonly seen in encephalitis.

Ms. L’s case shows the importance of early recognition of VZV infection. The diagnosis is confirmed through CSF analysis. There is an urgency to promptly conduct the LP to confirm the diagnosis and quickly initiate antiviral treatment to stop the progression of the infection and its life-threatening sequelae.

In the absence of underlying medical cause, typical treatment of catatonia involves the sublingual or IM administration of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam that can be repeated twice at 3-hour intervals if the patient’s symptoms do not resolve. ECT is indicated if the patient experiences minimal or no response to lorazepam.

The use of antipsychotics for catatonia is controversial. High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol and risperidone are not recommended due to increased risk of the progression of catatonia into neuroleptic malignant syndrome.7

Continue to: OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

Ms. L receives IV acyclovir 1,200 mg every 8 hours for 14 days. Just 48 hours after starting this antiviral medication, her bizarre behavior and catatonic features cease, and she returns to her baseline mental functioning. Olanzapine is discontinued, and lorazepam is progressively decreased. The CSF polymerase chain reaction assay indicates Ms. L is positive for VZV, which confirms the diagnosis of VZV encephalitis. A spine MRI is also performed and rules out myelitis as a sequela of the infection.

The authors’ observations

Chickenpox is caused by a primary encounter with VZV. Inside the ganglions of neurons, a dormant form of VZV resides. Its reactivation leads to the spread of the infection to the skin innervated by these neurons, causing shingles. Reactivation occurs in approximately 1 million people in the United States each year. The annual incidence is 5 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 people at age 60, and 8 to 11 cases per 1,000 people at age 70.8

In 2006, the FDA approved the first zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for use in nonimmunocompromised, VZV-seropositive adults age >60 (later lowered to age 50). This vaccine reduces the incidence of shingles by 51%, the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia by 66%, and the burden of illness by 61%. In 2017, the FDA approved a second VZV vaccine (Shingrix, recombinant nonlive vaccine). In 2021, Shingrix was approved for use in immunosuppressed patients.9

Reactivation of VZV starts with a prodromal phase, characterized by pain, itching, numbness, and dysesthesias in 1 to 3 dermatomes. A maculopapular rash appears on the affected area a few days later, evolving into vesicles that scab over in 10 days.10

Dissemination of the virus leading specifically to VZV encephalitis typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals and older patients. According to the World Health Organization, encephalitis is a life-threatening complication of VZV and occurs in 1 of 33,000 to 50,000 cases.11

Continue to: Delay in the diagnosis...

Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of VZV encephalitis can be detrimental or even fatal. Kodadhala et al12 found that the mortality rate for VZV encephalitis is 5% to 10% and ≤80% in immunosuppressed individuals.

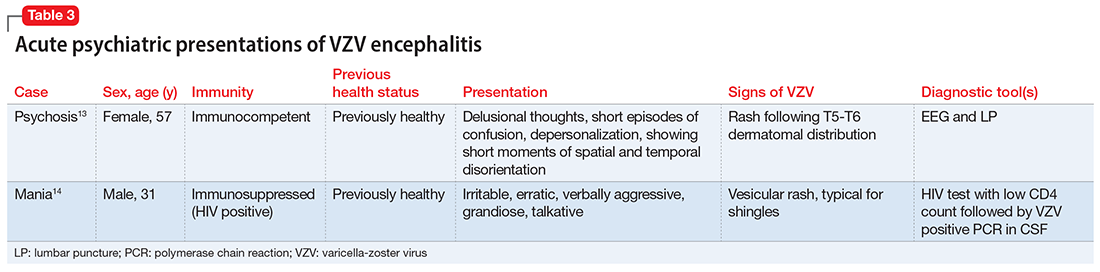

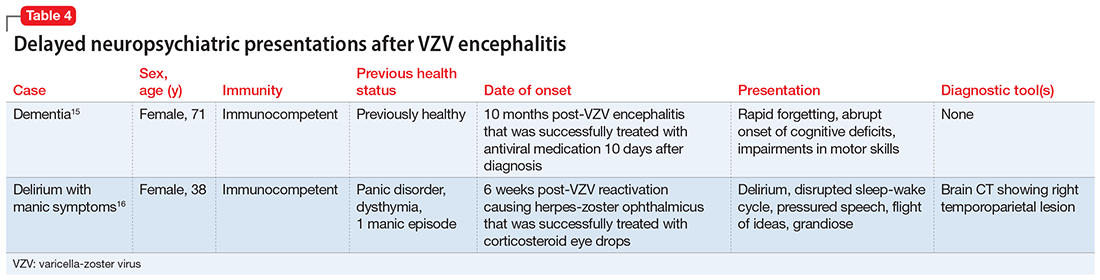

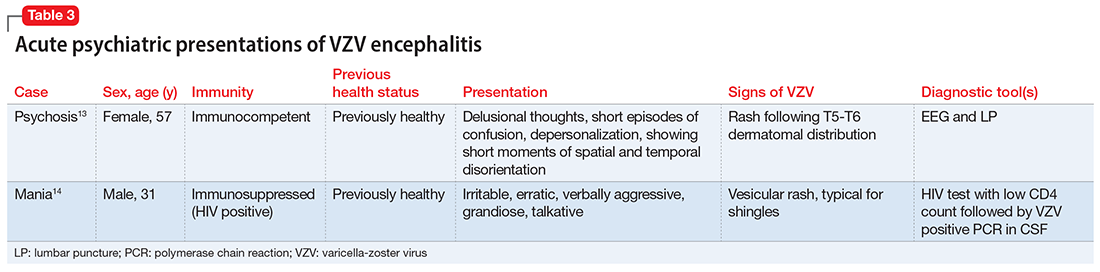

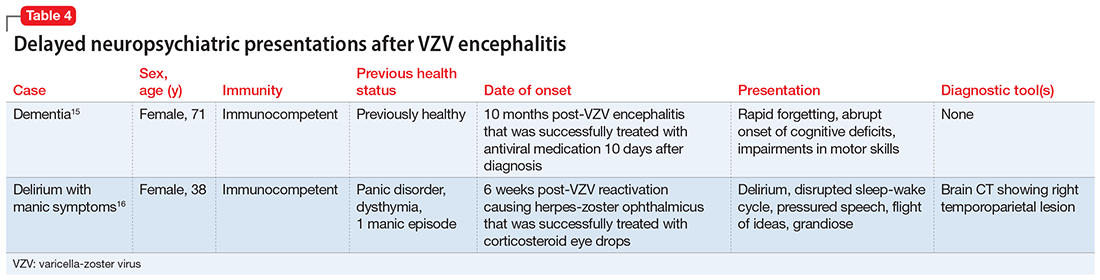

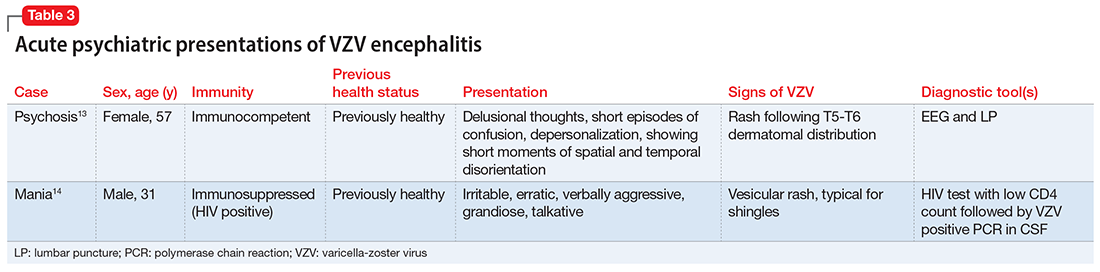

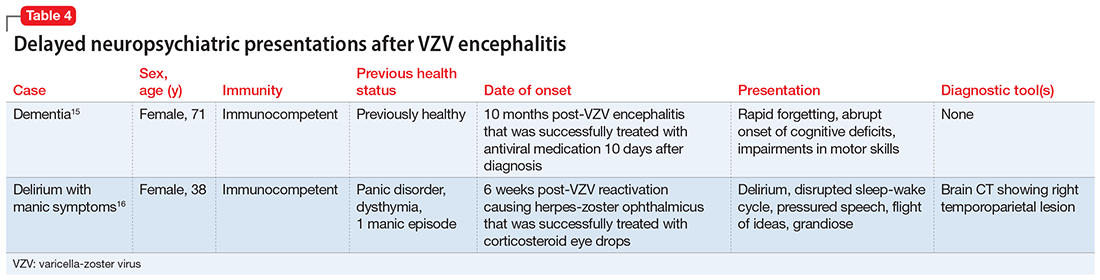

Sometimes, VZV encephalitis can masquerade as a psychiatric presentation. Few cases presenting with acute or delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms related to VZV encephalitis have been previously reported in the literature. Some are summarized in Table 313,14 and Table 4.15,16

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of catatonia as a presentation of VZV encephalitis. The catatonic presentation has been previously described in autoimmune encephalitis such as N-methyl-

Bottom Line

In the setting of a patient with an abrupt change in mental status/behavior, physicians must be aware of the importance of a thorough physical examination to better ascertain a diagnosis and to rule out an underlying medical disorder. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can result in encephalitis that might masquerade as a psychiatric presentation, including symptoms of catatonia.

Related Resources

- Baum ML, Johnson MC, Lizano P. Is it psychosis, or an autoimmune encephalitis? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8): 31-38,44. doi:10.12788/cp.0273

- Reinfold S. Are we failing to diagnose and treat the many faces of catatonia? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):e3-e5. doi:10.12788/cp.0208

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Sitavig

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sanders RD, Keshavan MS. Physical and neurologic examinations in neuropsychiatry. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7(1):18-29.

3. Howes DS, Lazoff M. Encephalitis workup. Medscape. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/791896-workup#c11

4. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

5. Fisle, CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Herpes_zoster_chest.png

6. John AR, Canaday DH. Herpes zoster in the older adult. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):811-826.

7. Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Catatonia and its treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):239-242.

8. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15016.

9. Raedler LA. Shingrix (zoster vaccine recombinant) a new vaccine approved for herpes zoster prevention in older adults. American Health & Drug Benefits, Ninth Annual Payers’ Guide. March 2018. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2018/april-2018-vol-11-ninth-annual-payers-guide/2567-shingrix-zoster-vaccine-recombinant-a-new-vaccine-approved-for-herpes-zoster-prevention-in-older-adults

10. Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes zoster. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

11. Lizzi J, Hill T, Jakubowski J. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(4):380-382.

12. Kodadhala V, Dessalegn M, Barned S, et al. 578: Varicella encephalitis: a rare complication of herpes zoster in an elderly patient. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):269.

13. Tremolizzo L, Tremolizzo S, Beghi M, et al. Mood disorder with psychotic symptoms and overlooked skin lesions: the strange case of Mrs. O. Riv Psichiatr. 2012;47(5):447-450.

14. George O, Daniel J, Forsyth S, et al. Mania presenting as a VZV encephalitis in the context of HIV. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):e230512.

15. Bangen KJ, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga CE, et al. Dementia following herpes zoster encephalitis. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(7):1193-1203.

16. McKenna KF, Warneke LB. Encephalitis associated with herpes zoster: a case report and review. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37(4):271-273.

17. Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, et al. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):620-630.

CASE Agitation and bizarre behavior

Ms. L, age 40, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status and bizarre behavior. Before arriving at the ED, she had experienced a severe headache and an episode of vomiting. At home she had been irritable and agitated, repetitively dressing and undressing, urinating outside the toilet, and opening and closing water faucets in the house. She also had stopped eating and drinking. Ms. L’s home medications consist of levothyroxine 100 mcg/d for hypothyroidism.

In the ED, Ms. L has severe psychomotor agitation. She is restless and displays purposeless repetitive movements with her hands. She is mostly mute, but does groan at times.

HISTORY Multiple trips to the ED

In addition to hypothyroidism, Ms. L has a history of migraines and asthma. Four days before presenting to the ED, she complained of a severe headache and generalized fatigue, with vomiting and nausea. Two days later, she presented to the ED at a different hospital and underwent a brain CT scan; the results were unremarkable. At that facility, a laboratory work-up—including complete blood count, urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, full liver function tests, amylase, lipase, bilirubin, thyroid function test, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin—was normal except for low thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (0.016 mIU/L). Ms. L was diagnosed with a severe migraine attack and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her endocrinologist.

Ms. L has no previous psychiatric history. Her family’s psychiatric history includes depression with psychotic features (mother), depression (maternal aunt), and generalized anxiety disorder (mother’s maternal aunt).

[polldaddy:11252938]

The authors’ observations

Catatonia is a behavioral syndrome with heterogeneous signs and symptoms. According to DSM-5, the diagnosis is considered when a patient presents with ≥3 of the 12 signs outlined in Table 1.1 It usually occurs in the context of an underlying psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or depression, or a medical disorder such as CNS infection or encephalopathy due to metabolic causes.1 Ms. L exhibited mutism, negativism, mannerism, stereotypy, and agitation and thus met the criteria for a catatonia diagnosis.

EVALUATION Unexpected finding on physical exam

In the ED, Ms. L is hemodynamically stable. Her blood pressure is 140/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; oxygen saturation is 98%; respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute; and temperature is 37.5° C. Results from a brain MRI and total body scan performed prior to admission are unremarkable.

Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric ward under the care of neurology for a psychiatry consultation. For approximately 24 hours, she receives IV diazepam 5 mg every 8 hours (due to the unavailability of lorazepam) for management of her catatonic symptoms, and olanzapine 10 mg every 8 hours orally as needed for agitation. Collateral history rules out a current mood episode or onset of psychosis in the weeks before she came to the ED. Diazepam improves Ms. L’s psychomotor agitation, which allows the primary team an opportunity to examine her.

Continue to: A physical exam reveals...

A physical exam reveals small vesicular lesions (1 to 2 cm in diameter) on an erythematous base on the left breast associated with an erythematous plaque with no evident vesicles on the left inner arm. The vesicular lesions display in a segmented pattern of dermatomal distribution.

[polldaddy:11252941]

The authors’ observations

Catatonic symptoms, coupled with psychomotor agitation in an immunocompetent middle-aged adult with a history of migraine headaches, strong family history of severe mental illness, and noncontributory findings on brain imaging, prompted a Psychiatry consultation and administration of psychotropic medications. A thorough physical exam revealing the small area of shingles and acute altered mental status prompted more aggressive investigations to explore the possibility of encephalitis.

Physicians should have a low index of suspicion for encephalitis (viral, bacterial, autoimmune, etc) and perform a lumbar puncture (LP) when necessary, despite the invasiveness of this test. A direct physical examination is often underutilized, notably in psychiatric patients, which can lead to the omission of important clinical information.2 Normal vital signs, blood workup, and MRI before admission are not sufficient to correctly guide diagnosis.

EVALUATION Additional lab results establish the diagnosis

An LP reveals Ms. L’s protein levels are 44 mg/dL, her glucose levels are 85 mg/dL, red blood cell count is 4/µL, and white blood cell count is 200/µL with 92% lymphocytes and 1% neutrophils. Ms. L’s CSF analysis profile indicates a viral CNS infection (Table 23).

[polldaddy:11252943]

The authors’ observations

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) are human neurotropic alphaherpesviruses that cause lifelong infections in ganglia, and their reactivation can come in the form of encephalitis.4

Continue to: Ms. L's clinical presentation...

Ms. L’s clinical presentation most likely implicated VZV. Skin lesions of VZV may look exactly like HSV, with clustered vesicles on an erythematous base (Figure5). However, VZV rash tends to follow a dermatomal distribution (as in Ms. L’s case), which can help distinguish it from herpetic lesions.

Cases of VZV infection have been increasing worldwide. It is usually seen in older adults or those with compromised immunity.6 Significantly higher rates of VZV complications have been reported in such patients. A serious complication is VZV encephalitis, which is rare but possible, even in healthy individuals.6 VZV encephalitis can present with atypical psychiatric features. Ms. L exhibited several symptoms of VZV encephalitis, which include headache, fever, vomiting, altered level of consciousness, and seizures. An EEG also showed intermittent generalized slow waves in the range of theta commonly seen in encephalitis.

Ms. L’s case shows the importance of early recognition of VZV infection. The diagnosis is confirmed through CSF analysis. There is an urgency to promptly conduct the LP to confirm the diagnosis and quickly initiate antiviral treatment to stop the progression of the infection and its life-threatening sequelae.

In the absence of underlying medical cause, typical treatment of catatonia involves the sublingual or IM administration of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam that can be repeated twice at 3-hour intervals if the patient’s symptoms do not resolve. ECT is indicated if the patient experiences minimal or no response to lorazepam.

The use of antipsychotics for catatonia is controversial. High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol and risperidone are not recommended due to increased risk of the progression of catatonia into neuroleptic malignant syndrome.7

Continue to: OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

Ms. L receives IV acyclovir 1,200 mg every 8 hours for 14 days. Just 48 hours after starting this antiviral medication, her bizarre behavior and catatonic features cease, and she returns to her baseline mental functioning. Olanzapine is discontinued, and lorazepam is progressively decreased. The CSF polymerase chain reaction assay indicates Ms. L is positive for VZV, which confirms the diagnosis of VZV encephalitis. A spine MRI is also performed and rules out myelitis as a sequela of the infection.

The authors’ observations

Chickenpox is caused by a primary encounter with VZV. Inside the ganglions of neurons, a dormant form of VZV resides. Its reactivation leads to the spread of the infection to the skin innervated by these neurons, causing shingles. Reactivation occurs in approximately 1 million people in the United States each year. The annual incidence is 5 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 people at age 60, and 8 to 11 cases per 1,000 people at age 70.8

In 2006, the FDA approved the first zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for use in nonimmunocompromised, VZV-seropositive adults age >60 (later lowered to age 50). This vaccine reduces the incidence of shingles by 51%, the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia by 66%, and the burden of illness by 61%. In 2017, the FDA approved a second VZV vaccine (Shingrix, recombinant nonlive vaccine). In 2021, Shingrix was approved for use in immunosuppressed patients.9

Reactivation of VZV starts with a prodromal phase, characterized by pain, itching, numbness, and dysesthesias in 1 to 3 dermatomes. A maculopapular rash appears on the affected area a few days later, evolving into vesicles that scab over in 10 days.10

Dissemination of the virus leading specifically to VZV encephalitis typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals and older patients. According to the World Health Organization, encephalitis is a life-threatening complication of VZV and occurs in 1 of 33,000 to 50,000 cases.11

Continue to: Delay in the diagnosis...

Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of VZV encephalitis can be detrimental or even fatal. Kodadhala et al12 found that the mortality rate for VZV encephalitis is 5% to 10% and ≤80% in immunosuppressed individuals.

Sometimes, VZV encephalitis can masquerade as a psychiatric presentation. Few cases presenting with acute or delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms related to VZV encephalitis have been previously reported in the literature. Some are summarized in Table 313,14 and Table 4.15,16

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of catatonia as a presentation of VZV encephalitis. The catatonic presentation has been previously described in autoimmune encephalitis such as N-methyl-

Bottom Line

In the setting of a patient with an abrupt change in mental status/behavior, physicians must be aware of the importance of a thorough physical examination to better ascertain a diagnosis and to rule out an underlying medical disorder. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can result in encephalitis that might masquerade as a psychiatric presentation, including symptoms of catatonia.

Related Resources

- Baum ML, Johnson MC, Lizano P. Is it psychosis, or an autoimmune encephalitis? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8): 31-38,44. doi:10.12788/cp.0273

- Reinfold S. Are we failing to diagnose and treat the many faces of catatonia? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):e3-e5. doi:10.12788/cp.0208

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Sitavig

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

CASE Agitation and bizarre behavior

Ms. L, age 40, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status and bizarre behavior. Before arriving at the ED, she had experienced a severe headache and an episode of vomiting. At home she had been irritable and agitated, repetitively dressing and undressing, urinating outside the toilet, and opening and closing water faucets in the house. She also had stopped eating and drinking. Ms. L’s home medications consist of levothyroxine 100 mcg/d for hypothyroidism.

In the ED, Ms. L has severe psychomotor agitation. She is restless and displays purposeless repetitive movements with her hands. She is mostly mute, but does groan at times.

HISTORY Multiple trips to the ED

In addition to hypothyroidism, Ms. L has a history of migraines and asthma. Four days before presenting to the ED, she complained of a severe headache and generalized fatigue, with vomiting and nausea. Two days later, she presented to the ED at a different hospital and underwent a brain CT scan; the results were unremarkable. At that facility, a laboratory work-up—including complete blood count, urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, full liver function tests, amylase, lipase, bilirubin, thyroid function test, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin—was normal except for low thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (0.016 mIU/L). Ms. L was diagnosed with a severe migraine attack and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her endocrinologist.

Ms. L has no previous psychiatric history. Her family’s psychiatric history includes depression with psychotic features (mother), depression (maternal aunt), and generalized anxiety disorder (mother’s maternal aunt).

[polldaddy:11252938]

The authors’ observations

Catatonia is a behavioral syndrome with heterogeneous signs and symptoms. According to DSM-5, the diagnosis is considered when a patient presents with ≥3 of the 12 signs outlined in Table 1.1 It usually occurs in the context of an underlying psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or depression, or a medical disorder such as CNS infection or encephalopathy due to metabolic causes.1 Ms. L exhibited mutism, negativism, mannerism, stereotypy, and agitation and thus met the criteria for a catatonia diagnosis.

EVALUATION Unexpected finding on physical exam

In the ED, Ms. L is hemodynamically stable. Her blood pressure is 140/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; oxygen saturation is 98%; respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute; and temperature is 37.5° C. Results from a brain MRI and total body scan performed prior to admission are unremarkable.

Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric ward under the care of neurology for a psychiatry consultation. For approximately 24 hours, she receives IV diazepam 5 mg every 8 hours (due to the unavailability of lorazepam) for management of her catatonic symptoms, and olanzapine 10 mg every 8 hours orally as needed for agitation. Collateral history rules out a current mood episode or onset of psychosis in the weeks before she came to the ED. Diazepam improves Ms. L’s psychomotor agitation, which allows the primary team an opportunity to examine her.

Continue to: A physical exam reveals...

A physical exam reveals small vesicular lesions (1 to 2 cm in diameter) on an erythematous base on the left breast associated with an erythematous plaque with no evident vesicles on the left inner arm. The vesicular lesions display in a segmented pattern of dermatomal distribution.

[polldaddy:11252941]

The authors’ observations

Catatonic symptoms, coupled with psychomotor agitation in an immunocompetent middle-aged adult with a history of migraine headaches, strong family history of severe mental illness, and noncontributory findings on brain imaging, prompted a Psychiatry consultation and administration of psychotropic medications. A thorough physical exam revealing the small area of shingles and acute altered mental status prompted more aggressive investigations to explore the possibility of encephalitis.

Physicians should have a low index of suspicion for encephalitis (viral, bacterial, autoimmune, etc) and perform a lumbar puncture (LP) when necessary, despite the invasiveness of this test. A direct physical examination is often underutilized, notably in psychiatric patients, which can lead to the omission of important clinical information.2 Normal vital signs, blood workup, and MRI before admission are not sufficient to correctly guide diagnosis.

EVALUATION Additional lab results establish the diagnosis

An LP reveals Ms. L’s protein levels are 44 mg/dL, her glucose levels are 85 mg/dL, red blood cell count is 4/µL, and white blood cell count is 200/µL with 92% lymphocytes and 1% neutrophils. Ms. L’s CSF analysis profile indicates a viral CNS infection (Table 23).

[polldaddy:11252943]

The authors’ observations

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) are human neurotropic alphaherpesviruses that cause lifelong infections in ganglia, and their reactivation can come in the form of encephalitis.4

Continue to: Ms. L's clinical presentation...

Ms. L’s clinical presentation most likely implicated VZV. Skin lesions of VZV may look exactly like HSV, with clustered vesicles on an erythematous base (Figure5). However, VZV rash tends to follow a dermatomal distribution (as in Ms. L’s case), which can help distinguish it from herpetic lesions.

Cases of VZV infection have been increasing worldwide. It is usually seen in older adults or those with compromised immunity.6 Significantly higher rates of VZV complications have been reported in such patients. A serious complication is VZV encephalitis, which is rare but possible, even in healthy individuals.6 VZV encephalitis can present with atypical psychiatric features. Ms. L exhibited several symptoms of VZV encephalitis, which include headache, fever, vomiting, altered level of consciousness, and seizures. An EEG also showed intermittent generalized slow waves in the range of theta commonly seen in encephalitis.

Ms. L’s case shows the importance of early recognition of VZV infection. The diagnosis is confirmed through CSF analysis. There is an urgency to promptly conduct the LP to confirm the diagnosis and quickly initiate antiviral treatment to stop the progression of the infection and its life-threatening sequelae.

In the absence of underlying medical cause, typical treatment of catatonia involves the sublingual or IM administration of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam that can be repeated twice at 3-hour intervals if the patient’s symptoms do not resolve. ECT is indicated if the patient experiences minimal or no response to lorazepam.

The use of antipsychotics for catatonia is controversial. High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol and risperidone are not recommended due to increased risk of the progression of catatonia into neuroleptic malignant syndrome.7

Continue to: OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

Ms. L receives IV acyclovir 1,200 mg every 8 hours for 14 days. Just 48 hours after starting this antiviral medication, her bizarre behavior and catatonic features cease, and she returns to her baseline mental functioning. Olanzapine is discontinued, and lorazepam is progressively decreased. The CSF polymerase chain reaction assay indicates Ms. L is positive for VZV, which confirms the diagnosis of VZV encephalitis. A spine MRI is also performed and rules out myelitis as a sequela of the infection.

The authors’ observations

Chickenpox is caused by a primary encounter with VZV. Inside the ganglions of neurons, a dormant form of VZV resides. Its reactivation leads to the spread of the infection to the skin innervated by these neurons, causing shingles. Reactivation occurs in approximately 1 million people in the United States each year. The annual incidence is 5 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 people at age 60, and 8 to 11 cases per 1,000 people at age 70.8

In 2006, the FDA approved the first zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for use in nonimmunocompromised, VZV-seropositive adults age >60 (later lowered to age 50). This vaccine reduces the incidence of shingles by 51%, the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia by 66%, and the burden of illness by 61%. In 2017, the FDA approved a second VZV vaccine (Shingrix, recombinant nonlive vaccine). In 2021, Shingrix was approved for use in immunosuppressed patients.9

Reactivation of VZV starts with a prodromal phase, characterized by pain, itching, numbness, and dysesthesias in 1 to 3 dermatomes. A maculopapular rash appears on the affected area a few days later, evolving into vesicles that scab over in 10 days.10

Dissemination of the virus leading specifically to VZV encephalitis typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals and older patients. According to the World Health Organization, encephalitis is a life-threatening complication of VZV and occurs in 1 of 33,000 to 50,000 cases.11

Continue to: Delay in the diagnosis...

Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of VZV encephalitis can be detrimental or even fatal. Kodadhala et al12 found that the mortality rate for VZV encephalitis is 5% to 10% and ≤80% in immunosuppressed individuals.

Sometimes, VZV encephalitis can masquerade as a psychiatric presentation. Few cases presenting with acute or delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms related to VZV encephalitis have been previously reported in the literature. Some are summarized in Table 313,14 and Table 4.15,16

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of catatonia as a presentation of VZV encephalitis. The catatonic presentation has been previously described in autoimmune encephalitis such as N-methyl-

Bottom Line

In the setting of a patient with an abrupt change in mental status/behavior, physicians must be aware of the importance of a thorough physical examination to better ascertain a diagnosis and to rule out an underlying medical disorder. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can result in encephalitis that might masquerade as a psychiatric presentation, including symptoms of catatonia.

Related Resources

- Baum ML, Johnson MC, Lizano P. Is it psychosis, or an autoimmune encephalitis? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8): 31-38,44. doi:10.12788/cp.0273

- Reinfold S. Are we failing to diagnose and treat the many faces of catatonia? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):e3-e5. doi:10.12788/cp.0208

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Sitavig

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sanders RD, Keshavan MS. Physical and neurologic examinations in neuropsychiatry. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7(1):18-29.

3. Howes DS, Lazoff M. Encephalitis workup. Medscape. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/791896-workup#c11

4. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

5. Fisle, CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Herpes_zoster_chest.png

6. John AR, Canaday DH. Herpes zoster in the older adult. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):811-826.

7. Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Catatonia and its treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):239-242.

8. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15016.

9. Raedler LA. Shingrix (zoster vaccine recombinant) a new vaccine approved for herpes zoster prevention in older adults. American Health & Drug Benefits, Ninth Annual Payers’ Guide. March 2018. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2018/april-2018-vol-11-ninth-annual-payers-guide/2567-shingrix-zoster-vaccine-recombinant-a-new-vaccine-approved-for-herpes-zoster-prevention-in-older-adults

10. Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes zoster. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

11. Lizzi J, Hill T, Jakubowski J. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(4):380-382.

12. Kodadhala V, Dessalegn M, Barned S, et al. 578: Varicella encephalitis: a rare complication of herpes zoster in an elderly patient. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):269.

13. Tremolizzo L, Tremolizzo S, Beghi M, et al. Mood disorder with psychotic symptoms and overlooked skin lesions: the strange case of Mrs. O. Riv Psichiatr. 2012;47(5):447-450.

14. George O, Daniel J, Forsyth S, et al. Mania presenting as a VZV encephalitis in the context of HIV. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):e230512.

15. Bangen KJ, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga CE, et al. Dementia following herpes zoster encephalitis. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(7):1193-1203.

16. McKenna KF, Warneke LB. Encephalitis associated with herpes zoster: a case report and review. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37(4):271-273.

17. Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, et al. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):620-630.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sanders RD, Keshavan MS. Physical and neurologic examinations in neuropsychiatry. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7(1):18-29.

3. Howes DS, Lazoff M. Encephalitis workup. Medscape. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/791896-workup#c11

4. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

5. Fisle, CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Herpes_zoster_chest.png

6. John AR, Canaday DH. Herpes zoster in the older adult. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):811-826.

7. Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Catatonia and its treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):239-242.

8. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15016.

9. Raedler LA. Shingrix (zoster vaccine recombinant) a new vaccine approved for herpes zoster prevention in older adults. American Health & Drug Benefits, Ninth Annual Payers’ Guide. March 2018. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2018/april-2018-vol-11-ninth-annual-payers-guide/2567-shingrix-zoster-vaccine-recombinant-a-new-vaccine-approved-for-herpes-zoster-prevention-in-older-adults

10. Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes zoster. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

11. Lizzi J, Hill T, Jakubowski J. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(4):380-382.

12. Kodadhala V, Dessalegn M, Barned S, et al. 578: Varicella encephalitis: a rare complication of herpes zoster in an elderly patient. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):269.

13. Tremolizzo L, Tremolizzo S, Beghi M, et al. Mood disorder with psychotic symptoms and overlooked skin lesions: the strange case of Mrs. O. Riv Psichiatr. 2012;47(5):447-450.

14. George O, Daniel J, Forsyth S, et al. Mania presenting as a VZV encephalitis in the context of HIV. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):e230512.

15. Bangen KJ, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga CE, et al. Dementia following herpes zoster encephalitis. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(7):1193-1203.

16. McKenna KF, Warneke LB. Encephalitis associated with herpes zoster: a case report and review. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37(4):271-273.

17. Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, et al. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):620-630.