User login

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is an acquired dermatosis that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles in association with visceral malignancies, such as esophageal, gastric, pulmonary, and bladder carcinomas. This condition may either be acquired or inherited.1

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a nonpruritic hyperkeratotic eruption predominantly on the palms and soles of 2 to 3 months’ duration (Figure 1A). Review of systems was remarkable for chronic anxiety, unintentional weight loss of 10 lb over the last 6 months, and a mild cough of 10 days’ duration. The differential diagnosis included eczematous dermatitis, tinea manuum, new-onset palmoplantar psoriasis, and PPK.

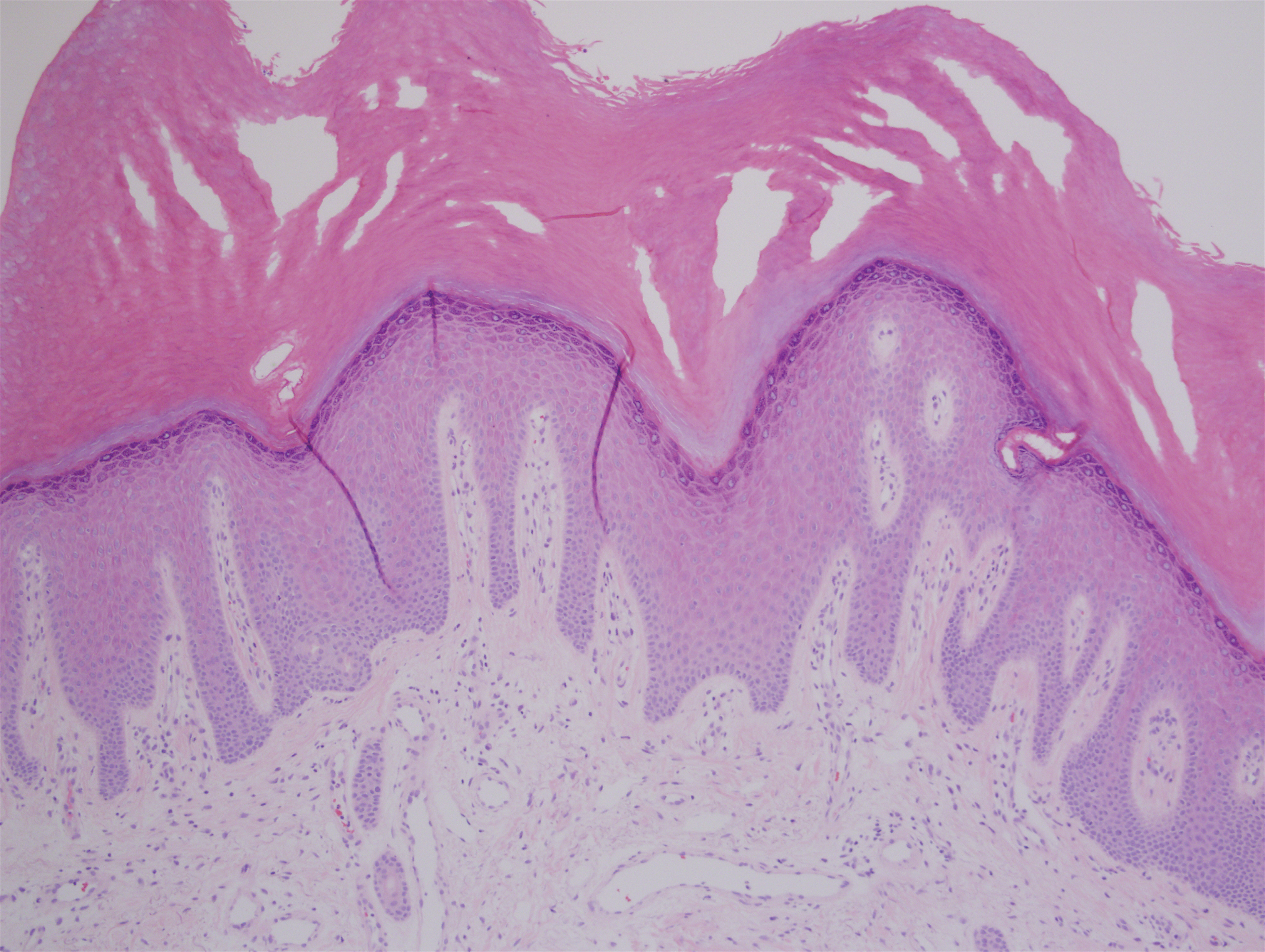

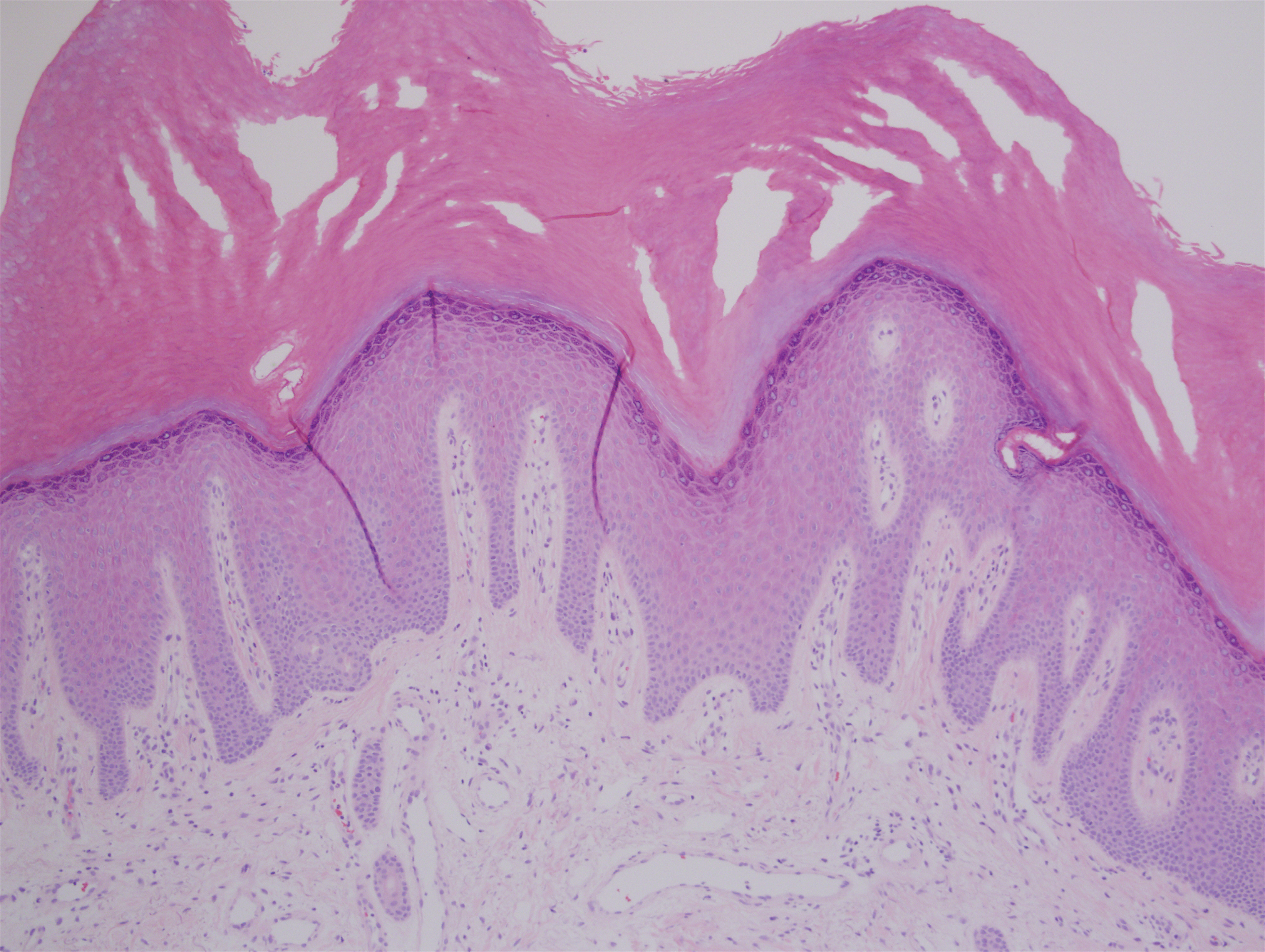

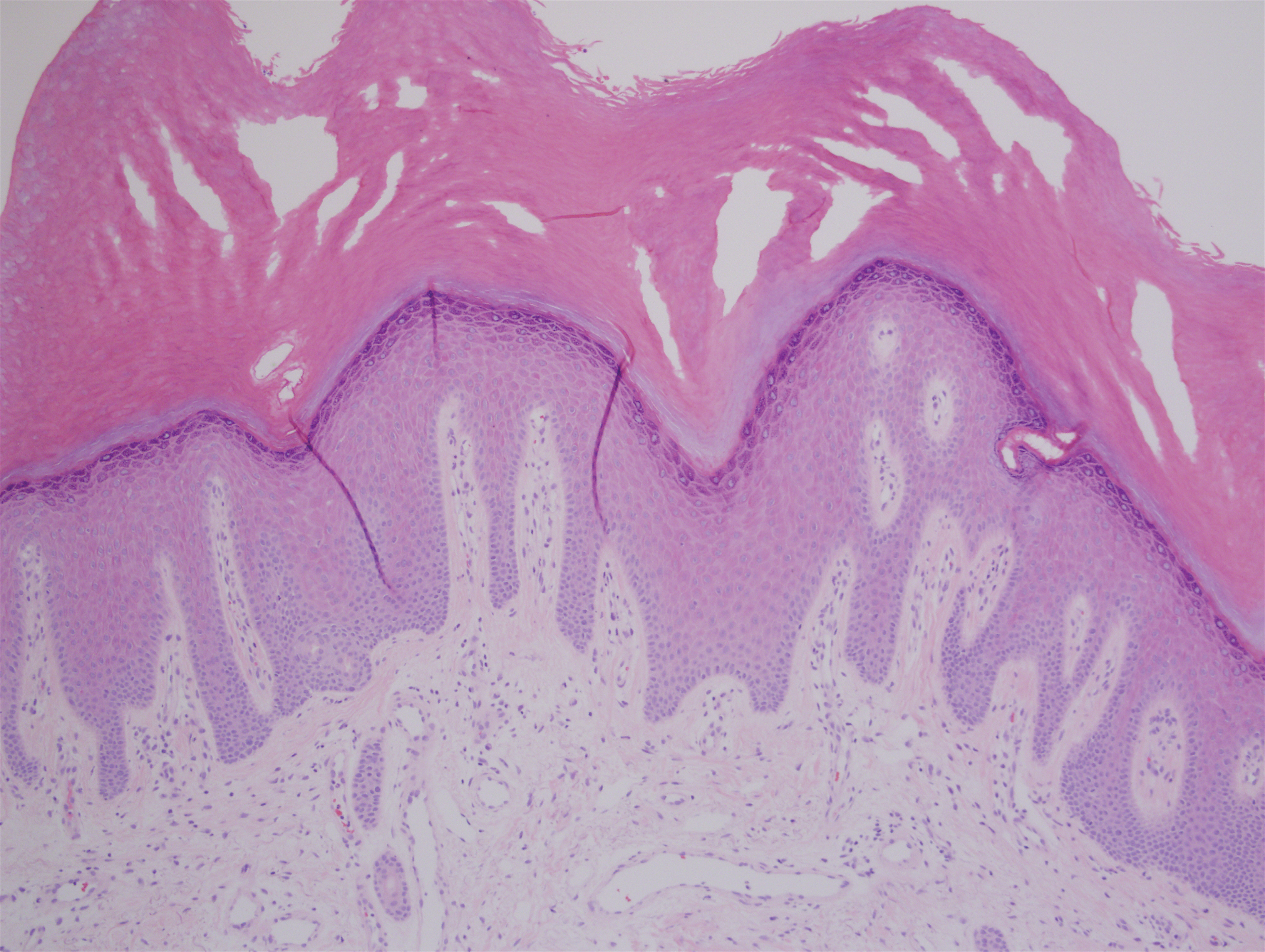

A punch biopsy of the medial hypothenar eminence of the left hand was performed, revealing notable lichenified hyperkeratosis with vascular ectasia (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements. Given the suspicion of PPK, multiple carcinoma markers were ordered. Cancer antigen 125 measured at 68 U/mL (reference range upper limit, 21 U/mL). Cancer antigen 27-29 was 50 U/mL (reference range, <38 U/mL) and cancer antigen 19-9 was 24 U/mL (reference range, <37 U/mL). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a large mass in the left lower lung associated with hilar lymphadenopathy. The patient was referred to oncology for further evaluation. Computed tomography–guided biopsy revealed metastatic uterine adenocarcinoma, which prompted subsequent chemotherapy. The combination of visceral malignancy with PPK led to the diagnosis of acquired PPK secondary to uterine cancer. After the completion of chemotherapy, the palmar dermatosis notably decreased (Figure 1B).

Comment

Paraneoplastic PPK is not uncommon. Ninety percent of acquired diffuse PPK is secondary to cancer,2 which occurs more frequently in male patients. Associated visceral malignancies include localized esophageal,3 myeloma,4 pulmonary, urinary/bladder,5 and gastric carcinoma.6 Paraneoplastic PPK in women is rare but has been linked to ovarian and breast carcinoma.7

The findings under light microscopy include thickening of any or all of the cell layers of the epidermis, which can include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis (Figure 2). A moderate amount of mononuclear cell infiltrates also can be visualized.

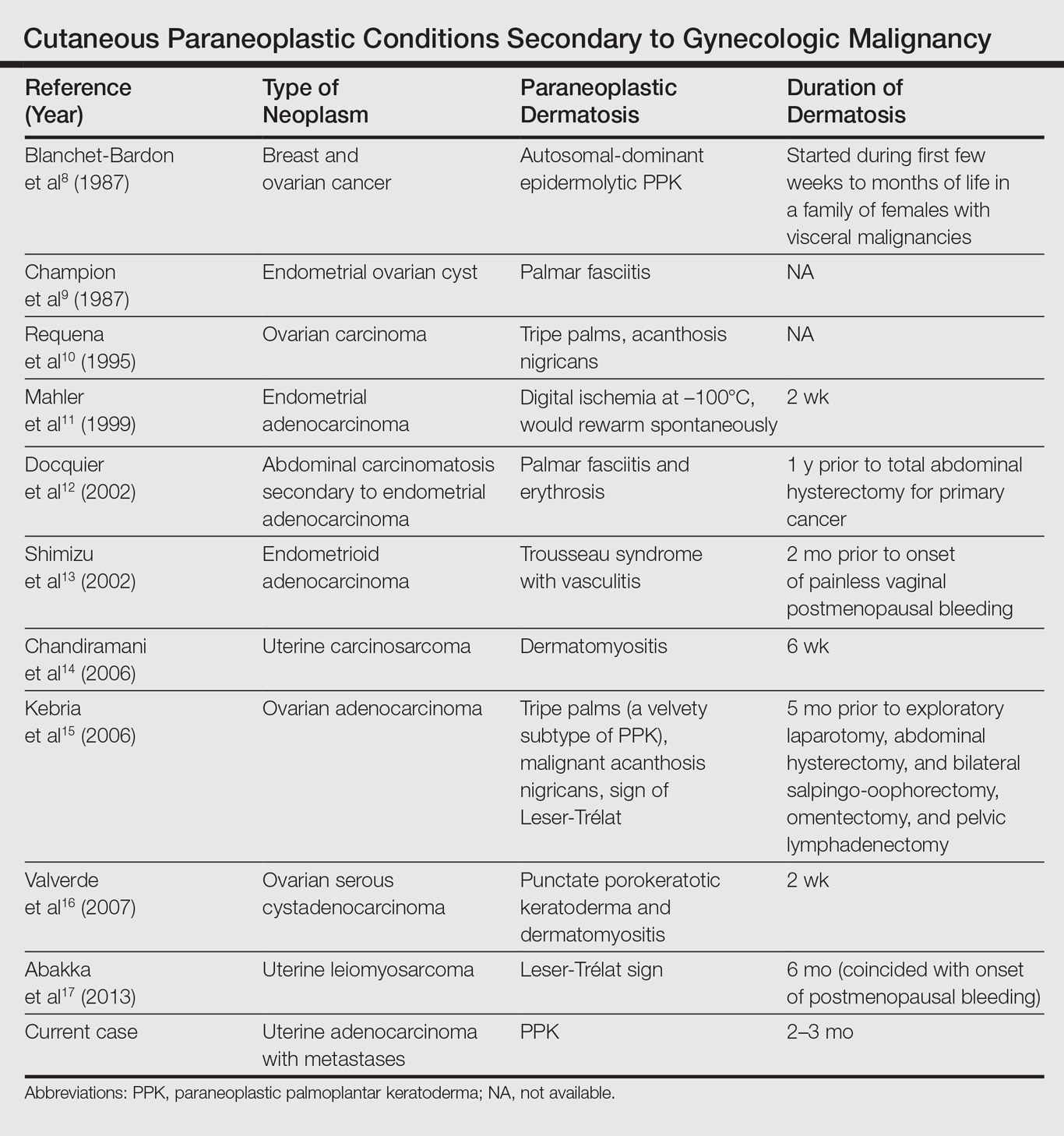

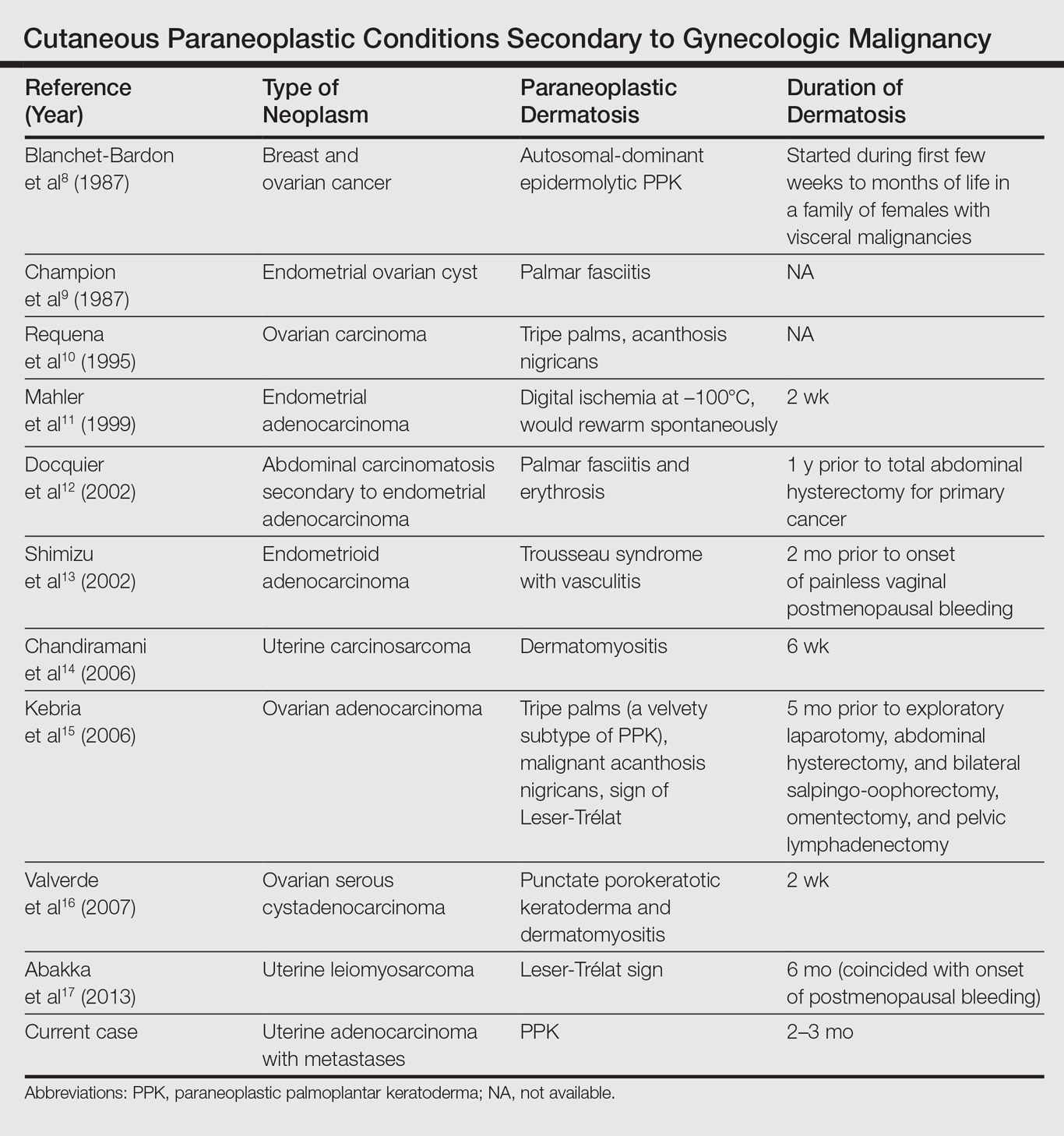

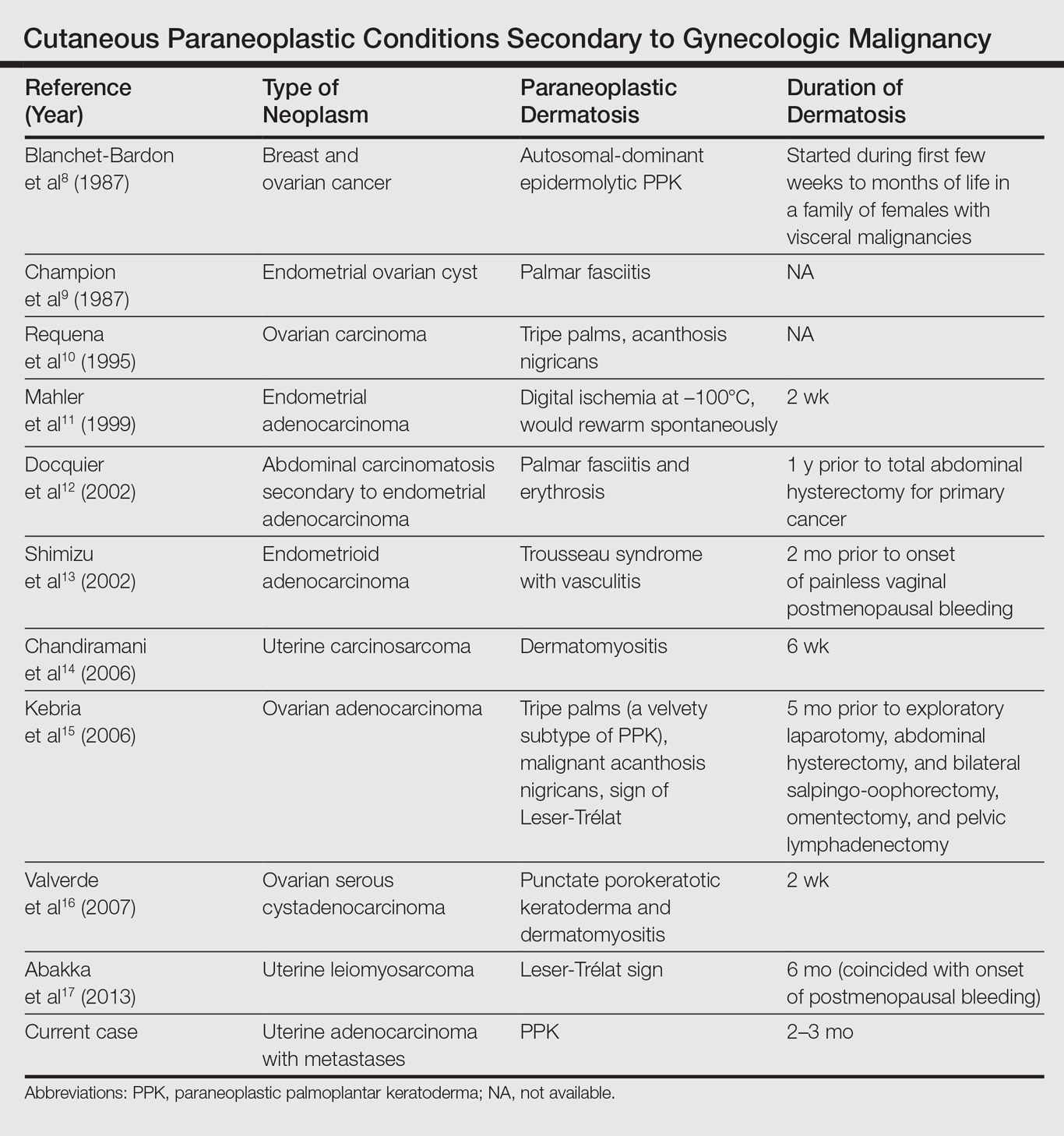

Palmoplantar keratoderma associated with uterine malignancy is rare. However, many other paraneoplastic dermatoses resulting from uterine cancer have been described as well as nonuterine gynecological malignancies (Table).8-17

The first step in managing acquired PPK is to determine its etiology via a complete history and a total-body skin examination. If findings are consistent with a hereditary PPK, then genetic workup is advised. Other suspected etiologies should be investigated via imaging and laboratory analysis.18

The first approach in managing acquired PPK is to treat the underlying cause. In prior cases, complete resolution of skin findings resulted once the malignancy or associated dermatosis had been treated.8-17 Adjunctive medication includes topical keratolytics (eg, urea, salicylic acid, lactic acid), topical retinoids, topical psoralen plus UVA, and topical corticosteroids.18 Vitamin A analogues have been found to be an effective treatment of many hyperkeratotic dermatoses.19 Isotretinoin and etretinate have been used to treat the cutaneous findings and prevent the onset and progression of esophageal malignancy of the inherited forms of PPK. The oral retinoid acitretin has been shown to rapidly resolve lesions, have persistent effects after 5 months of cessation, and have minimal side effects. Thus, it has been suggested as the first-line treatment of chronic PPK.19 One study found no response to topical keratolytics (urea cream and salicylic acid ointment) and a 2-week course of oral prednisone; however, low-dose oral acitretin 10 mg once daily resulted in notable improvement over several weeks.7 Physical debridement also may be necessary.18

Conclusion

Palmoplantar keratoderma is a condition that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. Acquired PPK often occurs as a paraneoplastic response as well as a stigma of other dermatoses. It occurs more frequently in male patients. Reports of PPK secondary to uterine cancer are not common in the literature. Management of PPK includes a complete history and total-body skin examination. After appropriate imaging and laboratory analysis, treatment of the underlying cause is the best approach. Adjunctive medications include topical keratolytics, topical retinoids, topical psoralen plus UVA, and topical corticosteroids. Oral isotretinoin and etretinate have demonstrated promising results.

- Zamiri M, van Steensel MA, Munro CS. Inherited palmoplantar keratodermas. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:538-548.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Silvers DN. Tripe palms and cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:165-173.

- Belmar P, Marquet A, Martín-Sáez E. Symmetric palmar hyperkeratosis and esophageal carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:149-150.

- Smith CH, Barker JN, Hay RJ. Diffuse plane xanthomatosis and acquired palmoplantar keratoderma in association with myeloma. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:286-289.

- Küchmeister B, Rasokat H. Acquired disseminated papulous palmar keratoses—a paraneoplastic syndrome in cancers of the urinary bladder and lung? [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1984;59:1123-1124.

- Stieler K, Blume-Peytavi U, Vogel A, et al. Hyperkeratoses as paraneoplastic syndrome [published online June 1, 2012]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:593-595.

- Vignale RA, Espasandín J, Paciel J, et al. Diagnostic value of keratosis palmaris as indicative sign of visceral cancer [in Spanish]. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1983;11:287-292.

- Blanchet-Bardon C, Nazzaro V, Chevrant-Breton J, et al. Hereditary epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma associated with breast and ovarian cancer in a large kindred. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:363-370.

- Champion GD, Saxon JA, Kossard S. The syndrome of palmar fibromatosis (fasciitis) and polyarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:1196-1198.

- Requena L, Aguilar A, Renedo G, et al. Tripe palms: a cutaneous marker of internal malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:492-495.

- Mahler V, Neureiter D, Kirchner T, et al. Digital ischemia as paraneoplastic marker of metastatic endometrial carcinoma [in German]. Hautarzt. 1999;50:748-752.

- Docquier Ch, Majois F, Mitine C. Palmar fasciitis and arthritis: association with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:63-65.

- Shimizu Y, Uchiyama S, Mori G, et al. A young patient with endometrioid adenocarcinoma who suffered Trousseau’s syndrome associated with vasculitis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2002;42:227-232.

- Chandiramani M, Joynson C, Panchal R, et al. Dermatomyositis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in carcinosarcoma of uterine origin. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18:641-648.

- Kebria MM, Belinson J, Kim R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and the sign of Leser-Trélat, a hint to the diagnosis of early stage ovarian cancer: a case report and review of the literature [published online January 27, 2006]. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:353-355.

- Valverde R, Sánchez-Caminero MP, Calzado L, et al. Dermatomyositis and punctate porokeratotic keratoderma as paraneoplastic syndrome of ovarian carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:358-360.

- Abakka S, Elhalouat H, Khoummane N, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma and Leser-Trélat sign. Lancet. 2013;381:88.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC 3rd. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Capella GL, Fracchiolla C, Frigerio E, et al. A controlled study of comparative efficacy of oral retinoids and topical betamethasone/salicylic acid for chronic hyperkeratotic palmoplantar dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:88-93.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is an acquired dermatosis that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles in association with visceral malignancies, such as esophageal, gastric, pulmonary, and bladder carcinomas. This condition may either be acquired or inherited.1

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a nonpruritic hyperkeratotic eruption predominantly on the palms and soles of 2 to 3 months’ duration (Figure 1A). Review of systems was remarkable for chronic anxiety, unintentional weight loss of 10 lb over the last 6 months, and a mild cough of 10 days’ duration. The differential diagnosis included eczematous dermatitis, tinea manuum, new-onset palmoplantar psoriasis, and PPK.

A punch biopsy of the medial hypothenar eminence of the left hand was performed, revealing notable lichenified hyperkeratosis with vascular ectasia (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements. Given the suspicion of PPK, multiple carcinoma markers were ordered. Cancer antigen 125 measured at 68 U/mL (reference range upper limit, 21 U/mL). Cancer antigen 27-29 was 50 U/mL (reference range, <38 U/mL) and cancer antigen 19-9 was 24 U/mL (reference range, <37 U/mL). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a large mass in the left lower lung associated with hilar lymphadenopathy. The patient was referred to oncology for further evaluation. Computed tomography–guided biopsy revealed metastatic uterine adenocarcinoma, which prompted subsequent chemotherapy. The combination of visceral malignancy with PPK led to the diagnosis of acquired PPK secondary to uterine cancer. After the completion of chemotherapy, the palmar dermatosis notably decreased (Figure 1B).

Comment

Paraneoplastic PPK is not uncommon. Ninety percent of acquired diffuse PPK is secondary to cancer,2 which occurs more frequently in male patients. Associated visceral malignancies include localized esophageal,3 myeloma,4 pulmonary, urinary/bladder,5 and gastric carcinoma.6 Paraneoplastic PPK in women is rare but has been linked to ovarian and breast carcinoma.7

The findings under light microscopy include thickening of any or all of the cell layers of the epidermis, which can include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis (Figure 2). A moderate amount of mononuclear cell infiltrates also can be visualized.

Palmoplantar keratoderma associated with uterine malignancy is rare. However, many other paraneoplastic dermatoses resulting from uterine cancer have been described as well as nonuterine gynecological malignancies (Table).8-17

The first step in managing acquired PPK is to determine its etiology via a complete history and a total-body skin examination. If findings are consistent with a hereditary PPK, then genetic workup is advised. Other suspected etiologies should be investigated via imaging and laboratory analysis.18

The first approach in managing acquired PPK is to treat the underlying cause. In prior cases, complete resolution of skin findings resulted once the malignancy or associated dermatosis had been treated.8-17 Adjunctive medication includes topical keratolytics (eg, urea, salicylic acid, lactic acid), topical retinoids, topical psoralen plus UVA, and topical corticosteroids.18 Vitamin A analogues have been found to be an effective treatment of many hyperkeratotic dermatoses.19 Isotretinoin and etretinate have been used to treat the cutaneous findings and prevent the onset and progression of esophageal malignancy of the inherited forms of PPK. The oral retinoid acitretin has been shown to rapidly resolve lesions, have persistent effects after 5 months of cessation, and have minimal side effects. Thus, it has been suggested as the first-line treatment of chronic PPK.19 One study found no response to topical keratolytics (urea cream and salicylic acid ointment) and a 2-week course of oral prednisone; however, low-dose oral acitretin 10 mg once daily resulted in notable improvement over several weeks.7 Physical debridement also may be necessary.18

Conclusion

Palmoplantar keratoderma is a condition that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. Acquired PPK often occurs as a paraneoplastic response as well as a stigma of other dermatoses. It occurs more frequently in male patients. Reports of PPK secondary to uterine cancer are not common in the literature. Management of PPK includes a complete history and total-body skin examination. After appropriate imaging and laboratory analysis, treatment of the underlying cause is the best approach. Adjunctive medications include topical keratolytics, topical retinoids, topical psoralen plus UVA, and topical corticosteroids. Oral isotretinoin and etretinate have demonstrated promising results.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is an acquired dermatosis that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles in association with visceral malignancies, such as esophageal, gastric, pulmonary, and bladder carcinomas. This condition may either be acquired or inherited.1

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a nonpruritic hyperkeratotic eruption predominantly on the palms and soles of 2 to 3 months’ duration (Figure 1A). Review of systems was remarkable for chronic anxiety, unintentional weight loss of 10 lb over the last 6 months, and a mild cough of 10 days’ duration. The differential diagnosis included eczematous dermatitis, tinea manuum, new-onset palmoplantar psoriasis, and PPK.

A punch biopsy of the medial hypothenar eminence of the left hand was performed, revealing notable lichenified hyperkeratosis with vascular ectasia (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements. Given the suspicion of PPK, multiple carcinoma markers were ordered. Cancer antigen 125 measured at 68 U/mL (reference range upper limit, 21 U/mL). Cancer antigen 27-29 was 50 U/mL (reference range, <38 U/mL) and cancer antigen 19-9 was 24 U/mL (reference range, <37 U/mL). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a large mass in the left lower lung associated with hilar lymphadenopathy. The patient was referred to oncology for further evaluation. Computed tomography–guided biopsy revealed metastatic uterine adenocarcinoma, which prompted subsequent chemotherapy. The combination of visceral malignancy with PPK led to the diagnosis of acquired PPK secondary to uterine cancer. After the completion of chemotherapy, the palmar dermatosis notably decreased (Figure 1B).

Comment

Paraneoplastic PPK is not uncommon. Ninety percent of acquired diffuse PPK is secondary to cancer,2 which occurs more frequently in male patients. Associated visceral malignancies include localized esophageal,3 myeloma,4 pulmonary, urinary/bladder,5 and gastric carcinoma.6 Paraneoplastic PPK in women is rare but has been linked to ovarian and breast carcinoma.7

The findings under light microscopy include thickening of any or all of the cell layers of the epidermis, which can include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis (Figure 2). A moderate amount of mononuclear cell infiltrates also can be visualized.

Palmoplantar keratoderma associated with uterine malignancy is rare. However, many other paraneoplastic dermatoses resulting from uterine cancer have been described as well as nonuterine gynecological malignancies (Table).8-17

The first step in managing acquired PPK is to determine its etiology via a complete history and a total-body skin examination. If findings are consistent with a hereditary PPK, then genetic workup is advised. Other suspected etiologies should be investigated via imaging and laboratory analysis.18

The first approach in managing acquired PPK is to treat the underlying cause. In prior cases, complete resolution of skin findings resulted once the malignancy or associated dermatosis had been treated.8-17 Adjunctive medication includes topical keratolytics (eg, urea, salicylic acid, lactic acid), topical retinoids, topical psoralen plus UVA, and topical corticosteroids.18 Vitamin A analogues have been found to be an effective treatment of many hyperkeratotic dermatoses.19 Isotretinoin and etretinate have been used to treat the cutaneous findings and prevent the onset and progression of esophageal malignancy of the inherited forms of PPK. The oral retinoid acitretin has been shown to rapidly resolve lesions, have persistent effects after 5 months of cessation, and have minimal side effects. Thus, it has been suggested as the first-line treatment of chronic PPK.19 One study found no response to topical keratolytics (urea cream and salicylic acid ointment) and a 2-week course of oral prednisone; however, low-dose oral acitretin 10 mg once daily resulted in notable improvement over several weeks.7 Physical debridement also may be necessary.18

Conclusion

Palmoplantar keratoderma is a condition that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. Acquired PPK often occurs as a paraneoplastic response as well as a stigma of other dermatoses. It occurs more frequently in male patients. Reports of PPK secondary to uterine cancer are not common in the literature. Management of PPK includes a complete history and total-body skin examination. After appropriate imaging and laboratory analysis, treatment of the underlying cause is the best approach. Adjunctive medications include topical keratolytics, topical retinoids, topical psoralen plus UVA, and topical corticosteroids. Oral isotretinoin and etretinate have demonstrated promising results.

- Zamiri M, van Steensel MA, Munro CS. Inherited palmoplantar keratodermas. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:538-548.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Silvers DN. Tripe palms and cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:165-173.

- Belmar P, Marquet A, Martín-Sáez E. Symmetric palmar hyperkeratosis and esophageal carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:149-150.

- Smith CH, Barker JN, Hay RJ. Diffuse plane xanthomatosis and acquired palmoplantar keratoderma in association with myeloma. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:286-289.

- Küchmeister B, Rasokat H. Acquired disseminated papulous palmar keratoses—a paraneoplastic syndrome in cancers of the urinary bladder and lung? [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1984;59:1123-1124.

- Stieler K, Blume-Peytavi U, Vogel A, et al. Hyperkeratoses as paraneoplastic syndrome [published online June 1, 2012]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:593-595.

- Vignale RA, Espasandín J, Paciel J, et al. Diagnostic value of keratosis palmaris as indicative sign of visceral cancer [in Spanish]. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1983;11:287-292.

- Blanchet-Bardon C, Nazzaro V, Chevrant-Breton J, et al. Hereditary epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma associated with breast and ovarian cancer in a large kindred. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:363-370.

- Champion GD, Saxon JA, Kossard S. The syndrome of palmar fibromatosis (fasciitis) and polyarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:1196-1198.

- Requena L, Aguilar A, Renedo G, et al. Tripe palms: a cutaneous marker of internal malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:492-495.

- Mahler V, Neureiter D, Kirchner T, et al. Digital ischemia as paraneoplastic marker of metastatic endometrial carcinoma [in German]. Hautarzt. 1999;50:748-752.

- Docquier Ch, Majois F, Mitine C. Palmar fasciitis and arthritis: association with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:63-65.

- Shimizu Y, Uchiyama S, Mori G, et al. A young patient with endometrioid adenocarcinoma who suffered Trousseau’s syndrome associated with vasculitis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2002;42:227-232.

- Chandiramani M, Joynson C, Panchal R, et al. Dermatomyositis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in carcinosarcoma of uterine origin. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18:641-648.

- Kebria MM, Belinson J, Kim R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and the sign of Leser-Trélat, a hint to the diagnosis of early stage ovarian cancer: a case report and review of the literature [published online January 27, 2006]. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:353-355.

- Valverde R, Sánchez-Caminero MP, Calzado L, et al. Dermatomyositis and punctate porokeratotic keratoderma as paraneoplastic syndrome of ovarian carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:358-360.

- Abakka S, Elhalouat H, Khoummane N, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma and Leser-Trélat sign. Lancet. 2013;381:88.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC 3rd. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Capella GL, Fracchiolla C, Frigerio E, et al. A controlled study of comparative efficacy of oral retinoids and topical betamethasone/salicylic acid for chronic hyperkeratotic palmoplantar dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:88-93.

- Zamiri M, van Steensel MA, Munro CS. Inherited palmoplantar keratodermas. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:538-548.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Silvers DN. Tripe palms and cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:165-173.

- Belmar P, Marquet A, Martín-Sáez E. Symmetric palmar hyperkeratosis and esophageal carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:149-150.

- Smith CH, Barker JN, Hay RJ. Diffuse plane xanthomatosis and acquired palmoplantar keratoderma in association with myeloma. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:286-289.

- Küchmeister B, Rasokat H. Acquired disseminated papulous palmar keratoses—a paraneoplastic syndrome in cancers of the urinary bladder and lung? [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1984;59:1123-1124.

- Stieler K, Blume-Peytavi U, Vogel A, et al. Hyperkeratoses as paraneoplastic syndrome [published online June 1, 2012]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:593-595.

- Vignale RA, Espasandín J, Paciel J, et al. Diagnostic value of keratosis palmaris as indicative sign of visceral cancer [in Spanish]. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1983;11:287-292.

- Blanchet-Bardon C, Nazzaro V, Chevrant-Breton J, et al. Hereditary epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma associated with breast and ovarian cancer in a large kindred. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:363-370.

- Champion GD, Saxon JA, Kossard S. The syndrome of palmar fibromatosis (fasciitis) and polyarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:1196-1198.

- Requena L, Aguilar A, Renedo G, et al. Tripe palms: a cutaneous marker of internal malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:492-495.

- Mahler V, Neureiter D, Kirchner T, et al. Digital ischemia as paraneoplastic marker of metastatic endometrial carcinoma [in German]. Hautarzt. 1999;50:748-752.

- Docquier Ch, Majois F, Mitine C. Palmar fasciitis and arthritis: association with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:63-65.

- Shimizu Y, Uchiyama S, Mori G, et al. A young patient with endometrioid adenocarcinoma who suffered Trousseau’s syndrome associated with vasculitis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2002;42:227-232.

- Chandiramani M, Joynson C, Panchal R, et al. Dermatomyositis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in carcinosarcoma of uterine origin. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18:641-648.

- Kebria MM, Belinson J, Kim R, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and the sign of Leser-Trélat, a hint to the diagnosis of early stage ovarian cancer: a case report and review of the literature [published online January 27, 2006]. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:353-355.

- Valverde R, Sánchez-Caminero MP, Calzado L, et al. Dermatomyositis and punctate porokeratotic keratoderma as paraneoplastic syndrome of ovarian carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:358-360.

- Abakka S, Elhalouat H, Khoummane N, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma and Leser-Trélat sign. Lancet. 2013;381:88.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC 3rd. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Capella GL, Fracchiolla C, Frigerio E, et al. A controlled study of comparative efficacy of oral retinoids and topical betamethasone/salicylic acid for chronic hyperkeratotic palmoplantar dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:88-93.

Practice Points

- Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is an acquired dermatosis that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles in association with visceral malignancies (eg, esophageal, gastric, pulmonary, and urinary/bladder carcinomas).

- Palmoplantar keratoderma secondary to uterine cancer is rare.

- Light microscopy shows thickening of any or all of the cell layers of the epidermis (hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis) and mononuclear cells.

- Management of acquired PPK includes treatment of the underlying malignancy. Adjunctive vitamin A analogues may be of additional utility.