User login

Thrombophilia is a prothrombotic state, either acquired or inherited, leading to a thrombotic predisposition.1 The most common heritable thrombophilias include factor V Leiden (FVL) and prothrombin G20210A. The most common acquired thrombophilia is the presence of phospholipid antibodies.1 Thrombotic risk varies with thrombophilia type. For example, deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C and protein S, and the presence of phospholipid antibodies, confer higher risk than FVL and prothrombin G20210A.2-5 Other thrombophilias (eg, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation, increased factor VIII activity) are relatively uncommon and/or their impact on thrombosis risk appears to be either minimal or unknown.1-6 There is little clinical evidence that testing for thrombophilia impacts subsequent thrombosis prevention.5,7,8 Multiple clinical guidelines and medical societies recommend against the routine and indiscriminate use of thrombophilia testing.8-13 In general, thrombophilia testing should be considered only if the result would lead to changes in anticoagulant initiation, intensity, and/or duration, or might inform interventions to prevent thrombosis in asymptomatic family members.8-13 However, thrombophilia testing rarely changes the acute management of a thrombotic event and may have harmful effects on patients and their family members because positive results may unnecessarily increase anxiety and negative results may provide false reassurance.6,14-18 The cost-effectiveness of thrombophilia testing is unknown. Economic models have sought to quantify cost-effectiveness, but conclusions from these studies are limited.7

The utility of thrombophilia testing in emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings is further limited because patients are often treated and discharged before thrombophilia test results are available. Additionally, in these settings, multiple factors increase the risk of false-positive or false-negative results (eg, acute thrombosis, acute illness, pregnancy, and anticoagulant therapy).19,20 The purpose of this study was to systematically assess thrombophilia testing patterns in the ED and hospitalized patients at an academic medical center and to quantify the proportion of tests associated with minimal clinical utility. We hypothesize that the majority of thrombophilia tests completed in the inpatient setting are associated with minimal clinical utility.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

This study was conducted at University of Utah Health Care (UUHC) University Hospital, a 488-bed academic medical center with a level I trauma center, primary stroke center, and 50-bed ED. Laboratory services for UUHC, including thrombophilia testing, are provided by a national reference laboratory, Associated Regional and University Pathologists Laboratories. This study included patients ≥18 years of age who received thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 1) during an ED visit or inpatient admission at University Hospital between July 1, 2014 and December 31, 2014. There were no exclusion criteria. An institutional electronic data repository was used to identify patients matching inclusion criteria. All study activities were reviewed and approved by the UUHC Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Outcomes

An electronic database query was used to identify patients, collect patient demographic information, and collect test characteristics. Each patient’s electronic medical record was manually reviewed to collect all other outcomes. Indication for thrombophilia testing was identified by manual review of provider notes. Thrombophilia tests occurring in situations associated with minimal clinical utility were defined as tests meeting at least one of the following criteria: patient discharged before test results were available for review; test type not recommended by published guidelines or by UUHC Thrombosis Service physicians for thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 2); test performed in situations associated with decreased accuracy; test was a duplicate test as a result of different thrombophilia panels containing identical tests; and test followed a provoked venous thromboembolism (VTE). Testing in situations associated with decreased accuracy are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 and included at least one of the following at the time of the test: anticoagulant therapy, acute thrombosis, pregnant or <8 weeks postpartum, and receiving estrogen-containing medications. Only test types known to be affected by the respective situation were included. Testing following a provoked VTE was defined as testing prompted by an acute thrombosis and performed within 3 months following major surgery (defined administratively as any surgery performed in an operating room), during pregnancy, <8 weeks postpartum, or while on estrogen-containing medications. Thrombophilia testing during anticoagulant therapy was defined as testing within 4 half-lives of anticoagulant administration based on medication administration records. Anticoagulant therapy changes were identified by comparing prior-to-admission and discharge medication lists.

Data Analysis

Patient and laboratory characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Data analysis was performed using Excel (Version 2013, Microsoft Corporation. Redmond, Washington).

RESULTS

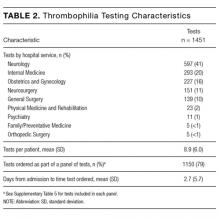

During the 6-month study period, 163 patients received at least 1 thrombophilia test during an ED visit or inpatient admission. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Tested patients were most commonly inpatients (96%) and female (71%). A total of 1451 thrombophilia tests were performed with a mean (± SD) of 8.9 ± 6.0 tests per patient. Testing characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Of the 39 different test types performed, the most commonly ordered were cardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies (9% each), lupus anticoagulant (9%), and β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG and IgM antibodies (8% each). When combined with testing for phosphatidyl antibodies, antiphospholipid tests accounted for 70% of all tests. Overall, 134 (9%) test results were positive. The mean time for results to become available was 2.2 ± 2.5 days. The frequency of test types with corresponding positivity rates and mean time for results to become available are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

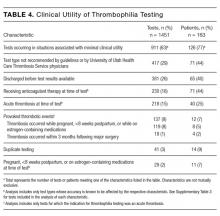

The indications for thrombophilia testing are summarized in Table 3. Ischemic stroke was the most common indication for testing (50% of tests; 35% of patients), followed by VTE (21% of tests; 21% of patients), and pregnancy-related conditions (eg, preeclampsia, intrauterine fetal demise; 15% of tests; 25% of patients). Overall, 911 tests (63%) occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility, with 126 patients (77%) receiving at least one of these tests (Table 4).

Anticoagulant therapy was changed in 43 patients (26%) in the following ways: initiated in 35 patients (21%), transitioned to a different anticoagulant in 6 patients (4%), and discontinued in 2 patients (1%). Of the 35 patients initiating anticoagulant therapy, 29 had documented thrombosis (24 had VTE, 4 had cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [CVST], and 1 had basilar artery thrombosis). Overall, 2 instances were identified in which initiation of anticoagulant therapy at discharge was in response to thrombophilia test results. In the first instance, warfarin without a parenteral anticoagulant bridge was initiated for a 54-year-old patient with a cryptogenic stroke who tested positive for β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, and protein S deficiency. In the second instance, warfarin with an enoxaparin bridge was initiated for a 26-year-old patient with a cryptogenic stroke who tested positive for β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG and IgM antibodies, cardiolipin IgG antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, protein C deficiency, and antithrombin deficiency. Of the 163 patients receiving thrombophilia testing, only 2 patients (1%) had clear documentation of being offered genetic consultation.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis, 1451 thrombophilia tests were performed in 163 patients over 6 months. Tested patients were relatively young, which is likely explained by the number of patients tested for pregnancy-related conditions and the fact that a stroke or VTE in younger patients more frequently prompted providers to suspect thrombophilia. Nearly three-fourths of patients were female, which is likely due to testing for pregnancy-related conditions and possibly diagnostic suspicion bias given the comparative predilection of antiphospholipid syndrome for women. The patient characteristics in our study are consistent with other studies evaluating thrombophilia testing.21,22

Thrombophilia testing was most frequently prompted by stroke, VTE, and pregnancy-related conditions. Only 26% of patients had acute thrombosis identified during the admission, primarily because of the high proportion of tests for cryptogenic strokes and pregnancy-related conditions. Thrombophilia testing is recommended in patients who have had a stroke when the stroke is considered to be cryptogenic after a standard stroke evaluation.23 Thrombophilia testing in pregnancy-related conditions is controversial but is often considered in situations such as stillbirths with severe placental pathology and/or significant growth restriction, or in mothers with a personal or family history of thrombosis.24 The proportion of testing for pregnancy-related conditions may be greater than at other institutions because UUHC Maternal Fetal Medicine is a referral center for women with conditions associated with hypercoagulability. Anticoagulant therapy was initiated in 21% of patients, but specifically in response to thrombophilia testing in only 2 instances; in most cases, anticoagulant therapy was initiated regardless of thrombophilia test results.

The results of this study confirm our hypothesis because the majority of thrombophilia tests occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility. Testing in these situations was not isolated to specific patients or medical services because 77% of tested patients received at least 1 test associated with minimal clinical utility. Our study took a conservative approach in defining scenarios associated with minimal clinical utility because other situations can also affect testing accuracy (eg, hepatic disease, nephrotic syndrome) but were not included in our analysis of this outcome.

The results of this study highlight opportunities to improve thrombophilia testing practices at our institution and may be generalizable to institutions with similar testing patterns. Because multiple medical services order thrombophilia tests, strategies to improve testing practices are still being determined. The results of this study can serve as a baseline for comparison after strategies are implemented. The most common situation associated with minimal clinical utility was the use of test types not generally recommended by guidelines or UUHC Thrombosis Service physicians for thrombophilia testing (eg, β2-glycoprotein 1 IgA antibodies, phosphatidyl antibodies). We intend to require a hematology or thrombosis specialty consult prior to ordering these tests. This intervention alone could potentially decrease unnecessary testing by a third. Another consideration is to require a specialty consult prior to any inpatient thrombophilia testing. This strategy has been found to decrease inappropriate testing at other institutions.21 We also intend to streamline available thrombophilia testing panels because a poorly designed panel could lead to ordering of multiple tests associated with minimal clinical utility. At least 12 different thrombophilia panels are currently available in our computerized physician order entry system (see Supplementary Table 5). We hypothesize that current panel designs contribute to providers inadvertently ordering unintended or duplicate tests and that reducing the number of available panels and clearly delineating what tests are contained in each panel is likely to reduce unnecessary testing. Other strategies being considered include using electronic clinical decision support tools, implementing strict ordering criteria for all inpatient testing, and establishing a thrombosis stewardship program.

Our study was unique in at least 2 ways. First, previous studies describing thrombophilia testing have described testing patterns for patients with specific indications (eg, VTE), whereas our study described all thrombophilia tests regardless of indication. This allows for testing pattern comparisons across indications and medical services, increasing the generalizability of our results. Second, this study quantifies tests occurring in situations associated with a practical definition of minimal clinical utility.

Our study has several limitations: (1) Many variables were reliant on provider notes and other documentation, which allows for potential misclassification of variables. (2) It was not always possible to determine the ultimate utility of each test in clinical management decisions, and our study did not investigate the impact of thrombophilia testing on duration of anticoagulant therapy. Additionally, select situations could benefit from testing regardless if anticoagulant therapy is altered (eg, informing contraceptive choices). (3) Testing performed following a provoked acute thrombosis was defined as testing within 3 months following administratively defined major surgery. This definition could have included some minor procedures that do not substantially increase VTE risk, resulting in underestimated clinical utility. (4) The UUHC University Hospital serves as a referral hospital for a large geographical area, and investigators did not have access to outpatient records for a large proportion of discharged patients. As a result, frequency of repeat testing could not be assessed, possibly resulting in overestimated clinical utility. (5) In categorizing indications for testing, testing for CVST was subcategorized under testing for ischemic stroke based on presenting symptoms rather than on underlying pathophysiology. The rationale for this categorization is that patients with CVST were often tested based on presenting symptoms. Additionally, tests for CVST were ordered by the neurology service, which also ordered tests for all other ischemic stroke indications. (6) The purpose of our study was to investigate the subset of the hospital’s patient population that received thrombophilia testing, and patients were identified by tests received and not by diagnosis codes. As a result, we are unable to provide the proportion of total patients treated at the hospital for specific conditions who were tested (eg, the proportion of stroke patients that received thrombophilia testing). (7) Current practice guidelines do not recommend testing for phosphatidyl antibodies, even when traditional antiphospholipid testing is negative.25-27 Although expert panels continue to explore associations between phosphatidyl antibodies and pregnancy morbidity and thrombotic events, the low level of evidence is insufficient to guide clinical management.28 Therefore, we categorized all phosphatidyl testing as associated with minimal clinical utility.

CONCLUSIONS

In a large academic medical center, the majority of tests occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility. Strategies to improve thrombophilia testing practices are needed in order to minimize potentially inappropriate testing, provide more cost-effective care, and promote value-driven outcomes.

Disclosure

S.W. received financial support for this submitted work via a Bristol-Myers-Squibb grant. G.F. received financial support from Portola Pharmaceuticals for consulting and lectures that were not related to this submitted work.

1. Franco RF, Reitsma PH. Genetic risk factors of venous thrombosis. Hum Genet. 2001;109(4):369-384. PubMed

2. Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Lindpaintner K, Stampfer MJ, Eisenberg PR, Miletich JP. Mutation in the gene coding for coagulation factor V and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thrombosis in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):912-917. PubMed

3. Koster T, Rosendaal FR, de Ronde H, Briët E, Vandenbroucke JP, Bertina RM. Venous thrombosis due to poor anticoagulant response to activated protein C: Leiden Thrombophilia Study. Lancet. 1993;342(8886-8887):1503-1506. PubMed

4. Margaglione M, Brancaccio V, Giuliani N, et al. Increased risk for venous thrombosis in carriers of the prothrombin G-->A20210 gene variant. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(2):89-93. PubMed

5. De Stefano V, Martinelli I, Mannucci PM, et al. The risk of recurrent deep venous thrombosis among heterozygous carriers of both factor V Leiden and the G20210A prothrombin mutation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:801-806. PubMed

6. Dickey TL. Can thrombophilia testing help to prevent recurrent VTE? Part 2. JAAPA. 2002;15(12):23-24, 27-29. PubMed

7. Simpson EL, Stevenson MD, Rawdin A, Papaioannou D. Thrombophilia testing in people with venous thromboembolism: systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(2):iii, ix-x, 1-91. PubMed

8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Venous thromboembolic disease: the management of venous thromboembolic diseases and the role of thrombophilia testing. NICE clinical guideline 144. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg144. Accessed on June 30, 2017.

9. Evalution of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: routine testing for factor V Leiden (R506Q) and prothrombin (20210G>A) mutations in adults with a history of idiopathic venous thromboembolism and their adult family members. Genet Med. 2011;13(1):67-76.

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-494S. PubMed

11. Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220. PubMed

12. Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely® campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:9-14. PubMed

13. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):154-164. PubMed

14. Christiansen SC, Cannegieter SC, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Thrombophilia, clinical factors, and recurrent venous thrombotic events. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2352-2361. PubMed

15. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, et al. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(1):1-7. PubMed

16. Miles JS, Miletich JP, Goldhaber SZ, Hennekens CH, Ridker PM. G20210A mutation in the prothrombin gene and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(1):215-218. PubMed

17. Eichinger S, Weltermann A, Mannhalter C, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in heterozygous carriers of factor V Leiden and a first spontaneous venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2357-2360. PubMed

18. Mazzolai L, Duchosal MA. Hereditary thrombophilia and venous thromboembolism: critical evaluation of the clinical implications of screening. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34(4):483-488. PubMed

19. Merriman L, Greaves M. Testing for thrombophilia: an evidence‐based approach. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(973):699-704. PubMed

20. Favaloro EJ, McDonald D, Lippi G. Laboratory investigation of thrombophilia: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35(7):695-710. PubMed

21. Shen YM, Tsai J, Taiwo E, et al. Analysis of thrombophilia test ordering practices at an academic center: a proposal for appropriate testing to reduce harm and cost. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155326. PubMed

22. Meyer MR, Witt DM, Delate T, et al. Thrombophilia testing patterns amongst patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2015;136(6):1160-1164. PubMed

23. Saver JL. Clinical practice: cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2065-2074. PubMed

24. ACOG practice bulletin no. 102: management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):748-761. PubMed

25. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):295-306. PubMed

26. Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW, Greer IA, Greaves M, British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2012;157(1):47-58. PubMed

27. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 132: antiphospholipid syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1514-1521. PubMed

28. Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Andreoli L, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force. Report on antiphospholipid syndrome laboratory diagnostics and trends. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(9):917-930. PubMed

Thrombophilia is a prothrombotic state, either acquired or inherited, leading to a thrombotic predisposition.1 The most common heritable thrombophilias include factor V Leiden (FVL) and prothrombin G20210A. The most common acquired thrombophilia is the presence of phospholipid antibodies.1 Thrombotic risk varies with thrombophilia type. For example, deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C and protein S, and the presence of phospholipid antibodies, confer higher risk than FVL and prothrombin G20210A.2-5 Other thrombophilias (eg, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation, increased factor VIII activity) are relatively uncommon and/or their impact on thrombosis risk appears to be either minimal or unknown.1-6 There is little clinical evidence that testing for thrombophilia impacts subsequent thrombosis prevention.5,7,8 Multiple clinical guidelines and medical societies recommend against the routine and indiscriminate use of thrombophilia testing.8-13 In general, thrombophilia testing should be considered only if the result would lead to changes in anticoagulant initiation, intensity, and/or duration, or might inform interventions to prevent thrombosis in asymptomatic family members.8-13 However, thrombophilia testing rarely changes the acute management of a thrombotic event and may have harmful effects on patients and their family members because positive results may unnecessarily increase anxiety and negative results may provide false reassurance.6,14-18 The cost-effectiveness of thrombophilia testing is unknown. Economic models have sought to quantify cost-effectiveness, but conclusions from these studies are limited.7

The utility of thrombophilia testing in emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings is further limited because patients are often treated and discharged before thrombophilia test results are available. Additionally, in these settings, multiple factors increase the risk of false-positive or false-negative results (eg, acute thrombosis, acute illness, pregnancy, and anticoagulant therapy).19,20 The purpose of this study was to systematically assess thrombophilia testing patterns in the ED and hospitalized patients at an academic medical center and to quantify the proportion of tests associated with minimal clinical utility. We hypothesize that the majority of thrombophilia tests completed in the inpatient setting are associated with minimal clinical utility.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

This study was conducted at University of Utah Health Care (UUHC) University Hospital, a 488-bed academic medical center with a level I trauma center, primary stroke center, and 50-bed ED. Laboratory services for UUHC, including thrombophilia testing, are provided by a national reference laboratory, Associated Regional and University Pathologists Laboratories. This study included patients ≥18 years of age who received thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 1) during an ED visit or inpatient admission at University Hospital between July 1, 2014 and December 31, 2014. There were no exclusion criteria. An institutional electronic data repository was used to identify patients matching inclusion criteria. All study activities were reviewed and approved by the UUHC Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Outcomes

An electronic database query was used to identify patients, collect patient demographic information, and collect test characteristics. Each patient’s electronic medical record was manually reviewed to collect all other outcomes. Indication for thrombophilia testing was identified by manual review of provider notes. Thrombophilia tests occurring in situations associated with minimal clinical utility were defined as tests meeting at least one of the following criteria: patient discharged before test results were available for review; test type not recommended by published guidelines or by UUHC Thrombosis Service physicians for thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 2); test performed in situations associated with decreased accuracy; test was a duplicate test as a result of different thrombophilia panels containing identical tests; and test followed a provoked venous thromboembolism (VTE). Testing in situations associated with decreased accuracy are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 and included at least one of the following at the time of the test: anticoagulant therapy, acute thrombosis, pregnant or <8 weeks postpartum, and receiving estrogen-containing medications. Only test types known to be affected by the respective situation were included. Testing following a provoked VTE was defined as testing prompted by an acute thrombosis and performed within 3 months following major surgery (defined administratively as any surgery performed in an operating room), during pregnancy, <8 weeks postpartum, or while on estrogen-containing medications. Thrombophilia testing during anticoagulant therapy was defined as testing within 4 half-lives of anticoagulant administration based on medication administration records. Anticoagulant therapy changes were identified by comparing prior-to-admission and discharge medication lists.

Data Analysis

Patient and laboratory characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Data analysis was performed using Excel (Version 2013, Microsoft Corporation. Redmond, Washington).

RESULTS

During the 6-month study period, 163 patients received at least 1 thrombophilia test during an ED visit or inpatient admission. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Tested patients were most commonly inpatients (96%) and female (71%). A total of 1451 thrombophilia tests were performed with a mean (± SD) of 8.9 ± 6.0 tests per patient. Testing characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Of the 39 different test types performed, the most commonly ordered were cardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies (9% each), lupus anticoagulant (9%), and β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG and IgM antibodies (8% each). When combined with testing for phosphatidyl antibodies, antiphospholipid tests accounted for 70% of all tests. Overall, 134 (9%) test results were positive. The mean time for results to become available was 2.2 ± 2.5 days. The frequency of test types with corresponding positivity rates and mean time for results to become available are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

The indications for thrombophilia testing are summarized in Table 3. Ischemic stroke was the most common indication for testing (50% of tests; 35% of patients), followed by VTE (21% of tests; 21% of patients), and pregnancy-related conditions (eg, preeclampsia, intrauterine fetal demise; 15% of tests; 25% of patients). Overall, 911 tests (63%) occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility, with 126 patients (77%) receiving at least one of these tests (Table 4).

Anticoagulant therapy was changed in 43 patients (26%) in the following ways: initiated in 35 patients (21%), transitioned to a different anticoagulant in 6 patients (4%), and discontinued in 2 patients (1%). Of the 35 patients initiating anticoagulant therapy, 29 had documented thrombosis (24 had VTE, 4 had cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [CVST], and 1 had basilar artery thrombosis). Overall, 2 instances were identified in which initiation of anticoagulant therapy at discharge was in response to thrombophilia test results. In the first instance, warfarin without a parenteral anticoagulant bridge was initiated for a 54-year-old patient with a cryptogenic stroke who tested positive for β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, and protein S deficiency. In the second instance, warfarin with an enoxaparin bridge was initiated for a 26-year-old patient with a cryptogenic stroke who tested positive for β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG and IgM antibodies, cardiolipin IgG antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, protein C deficiency, and antithrombin deficiency. Of the 163 patients receiving thrombophilia testing, only 2 patients (1%) had clear documentation of being offered genetic consultation.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis, 1451 thrombophilia tests were performed in 163 patients over 6 months. Tested patients were relatively young, which is likely explained by the number of patients tested for pregnancy-related conditions and the fact that a stroke or VTE in younger patients more frequently prompted providers to suspect thrombophilia. Nearly three-fourths of patients were female, which is likely due to testing for pregnancy-related conditions and possibly diagnostic suspicion bias given the comparative predilection of antiphospholipid syndrome for women. The patient characteristics in our study are consistent with other studies evaluating thrombophilia testing.21,22

Thrombophilia testing was most frequently prompted by stroke, VTE, and pregnancy-related conditions. Only 26% of patients had acute thrombosis identified during the admission, primarily because of the high proportion of tests for cryptogenic strokes and pregnancy-related conditions. Thrombophilia testing is recommended in patients who have had a stroke when the stroke is considered to be cryptogenic after a standard stroke evaluation.23 Thrombophilia testing in pregnancy-related conditions is controversial but is often considered in situations such as stillbirths with severe placental pathology and/or significant growth restriction, or in mothers with a personal or family history of thrombosis.24 The proportion of testing for pregnancy-related conditions may be greater than at other institutions because UUHC Maternal Fetal Medicine is a referral center for women with conditions associated with hypercoagulability. Anticoagulant therapy was initiated in 21% of patients, but specifically in response to thrombophilia testing in only 2 instances; in most cases, anticoagulant therapy was initiated regardless of thrombophilia test results.

The results of this study confirm our hypothesis because the majority of thrombophilia tests occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility. Testing in these situations was not isolated to specific patients or medical services because 77% of tested patients received at least 1 test associated with minimal clinical utility. Our study took a conservative approach in defining scenarios associated with minimal clinical utility because other situations can also affect testing accuracy (eg, hepatic disease, nephrotic syndrome) but were not included in our analysis of this outcome.

The results of this study highlight opportunities to improve thrombophilia testing practices at our institution and may be generalizable to institutions with similar testing patterns. Because multiple medical services order thrombophilia tests, strategies to improve testing practices are still being determined. The results of this study can serve as a baseline for comparison after strategies are implemented. The most common situation associated with minimal clinical utility was the use of test types not generally recommended by guidelines or UUHC Thrombosis Service physicians for thrombophilia testing (eg, β2-glycoprotein 1 IgA antibodies, phosphatidyl antibodies). We intend to require a hematology or thrombosis specialty consult prior to ordering these tests. This intervention alone could potentially decrease unnecessary testing by a third. Another consideration is to require a specialty consult prior to any inpatient thrombophilia testing. This strategy has been found to decrease inappropriate testing at other institutions.21 We also intend to streamline available thrombophilia testing panels because a poorly designed panel could lead to ordering of multiple tests associated with minimal clinical utility. At least 12 different thrombophilia panels are currently available in our computerized physician order entry system (see Supplementary Table 5). We hypothesize that current panel designs contribute to providers inadvertently ordering unintended or duplicate tests and that reducing the number of available panels and clearly delineating what tests are contained in each panel is likely to reduce unnecessary testing. Other strategies being considered include using electronic clinical decision support tools, implementing strict ordering criteria for all inpatient testing, and establishing a thrombosis stewardship program.

Our study was unique in at least 2 ways. First, previous studies describing thrombophilia testing have described testing patterns for patients with specific indications (eg, VTE), whereas our study described all thrombophilia tests regardless of indication. This allows for testing pattern comparisons across indications and medical services, increasing the generalizability of our results. Second, this study quantifies tests occurring in situations associated with a practical definition of minimal clinical utility.

Our study has several limitations: (1) Many variables were reliant on provider notes and other documentation, which allows for potential misclassification of variables. (2) It was not always possible to determine the ultimate utility of each test in clinical management decisions, and our study did not investigate the impact of thrombophilia testing on duration of anticoagulant therapy. Additionally, select situations could benefit from testing regardless if anticoagulant therapy is altered (eg, informing contraceptive choices). (3) Testing performed following a provoked acute thrombosis was defined as testing within 3 months following administratively defined major surgery. This definition could have included some minor procedures that do not substantially increase VTE risk, resulting in underestimated clinical utility. (4) The UUHC University Hospital serves as a referral hospital for a large geographical area, and investigators did not have access to outpatient records for a large proportion of discharged patients. As a result, frequency of repeat testing could not be assessed, possibly resulting in overestimated clinical utility. (5) In categorizing indications for testing, testing for CVST was subcategorized under testing for ischemic stroke based on presenting symptoms rather than on underlying pathophysiology. The rationale for this categorization is that patients with CVST were often tested based on presenting symptoms. Additionally, tests for CVST were ordered by the neurology service, which also ordered tests for all other ischemic stroke indications. (6) The purpose of our study was to investigate the subset of the hospital’s patient population that received thrombophilia testing, and patients were identified by tests received and not by diagnosis codes. As a result, we are unable to provide the proportion of total patients treated at the hospital for specific conditions who were tested (eg, the proportion of stroke patients that received thrombophilia testing). (7) Current practice guidelines do not recommend testing for phosphatidyl antibodies, even when traditional antiphospholipid testing is negative.25-27 Although expert panels continue to explore associations between phosphatidyl antibodies and pregnancy morbidity and thrombotic events, the low level of evidence is insufficient to guide clinical management.28 Therefore, we categorized all phosphatidyl testing as associated with minimal clinical utility.

CONCLUSIONS

In a large academic medical center, the majority of tests occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility. Strategies to improve thrombophilia testing practices are needed in order to minimize potentially inappropriate testing, provide more cost-effective care, and promote value-driven outcomes.

Disclosure

S.W. received financial support for this submitted work via a Bristol-Myers-Squibb grant. G.F. received financial support from Portola Pharmaceuticals for consulting and lectures that were not related to this submitted work.

Thrombophilia is a prothrombotic state, either acquired or inherited, leading to a thrombotic predisposition.1 The most common heritable thrombophilias include factor V Leiden (FVL) and prothrombin G20210A. The most common acquired thrombophilia is the presence of phospholipid antibodies.1 Thrombotic risk varies with thrombophilia type. For example, deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C and protein S, and the presence of phospholipid antibodies, confer higher risk than FVL and prothrombin G20210A.2-5 Other thrombophilias (eg, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation, increased factor VIII activity) are relatively uncommon and/or their impact on thrombosis risk appears to be either minimal or unknown.1-6 There is little clinical evidence that testing for thrombophilia impacts subsequent thrombosis prevention.5,7,8 Multiple clinical guidelines and medical societies recommend against the routine and indiscriminate use of thrombophilia testing.8-13 In general, thrombophilia testing should be considered only if the result would lead to changes in anticoagulant initiation, intensity, and/or duration, or might inform interventions to prevent thrombosis in asymptomatic family members.8-13 However, thrombophilia testing rarely changes the acute management of a thrombotic event and may have harmful effects on patients and their family members because positive results may unnecessarily increase anxiety and negative results may provide false reassurance.6,14-18 The cost-effectiveness of thrombophilia testing is unknown. Economic models have sought to quantify cost-effectiveness, but conclusions from these studies are limited.7

The utility of thrombophilia testing in emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings is further limited because patients are often treated and discharged before thrombophilia test results are available. Additionally, in these settings, multiple factors increase the risk of false-positive or false-negative results (eg, acute thrombosis, acute illness, pregnancy, and anticoagulant therapy).19,20 The purpose of this study was to systematically assess thrombophilia testing patterns in the ED and hospitalized patients at an academic medical center and to quantify the proportion of tests associated with minimal clinical utility. We hypothesize that the majority of thrombophilia tests completed in the inpatient setting are associated with minimal clinical utility.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

This study was conducted at University of Utah Health Care (UUHC) University Hospital, a 488-bed academic medical center with a level I trauma center, primary stroke center, and 50-bed ED. Laboratory services for UUHC, including thrombophilia testing, are provided by a national reference laboratory, Associated Regional and University Pathologists Laboratories. This study included patients ≥18 years of age who received thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 1) during an ED visit or inpatient admission at University Hospital between July 1, 2014 and December 31, 2014. There were no exclusion criteria. An institutional electronic data repository was used to identify patients matching inclusion criteria. All study activities were reviewed and approved by the UUHC Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Outcomes

An electronic database query was used to identify patients, collect patient demographic information, and collect test characteristics. Each patient’s electronic medical record was manually reviewed to collect all other outcomes. Indication for thrombophilia testing was identified by manual review of provider notes. Thrombophilia tests occurring in situations associated with minimal clinical utility were defined as tests meeting at least one of the following criteria: patient discharged before test results were available for review; test type not recommended by published guidelines or by UUHC Thrombosis Service physicians for thrombophilia testing (Supplementary Table 2); test performed in situations associated with decreased accuracy; test was a duplicate test as a result of different thrombophilia panels containing identical tests; and test followed a provoked venous thromboembolism (VTE). Testing in situations associated with decreased accuracy are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 and included at least one of the following at the time of the test: anticoagulant therapy, acute thrombosis, pregnant or <8 weeks postpartum, and receiving estrogen-containing medications. Only test types known to be affected by the respective situation were included. Testing following a provoked VTE was defined as testing prompted by an acute thrombosis and performed within 3 months following major surgery (defined administratively as any surgery performed in an operating room), during pregnancy, <8 weeks postpartum, or while on estrogen-containing medications. Thrombophilia testing during anticoagulant therapy was defined as testing within 4 half-lives of anticoagulant administration based on medication administration records. Anticoagulant therapy changes were identified by comparing prior-to-admission and discharge medication lists.

Data Analysis

Patient and laboratory characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Data analysis was performed using Excel (Version 2013, Microsoft Corporation. Redmond, Washington).

RESULTS

During the 6-month study period, 163 patients received at least 1 thrombophilia test during an ED visit or inpatient admission. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Tested patients were most commonly inpatients (96%) and female (71%). A total of 1451 thrombophilia tests were performed with a mean (± SD) of 8.9 ± 6.0 tests per patient. Testing characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Of the 39 different test types performed, the most commonly ordered were cardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies (9% each), lupus anticoagulant (9%), and β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG and IgM antibodies (8% each). When combined with testing for phosphatidyl antibodies, antiphospholipid tests accounted for 70% of all tests. Overall, 134 (9%) test results were positive. The mean time for results to become available was 2.2 ± 2.5 days. The frequency of test types with corresponding positivity rates and mean time for results to become available are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

The indications for thrombophilia testing are summarized in Table 3. Ischemic stroke was the most common indication for testing (50% of tests; 35% of patients), followed by VTE (21% of tests; 21% of patients), and pregnancy-related conditions (eg, preeclampsia, intrauterine fetal demise; 15% of tests; 25% of patients). Overall, 911 tests (63%) occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility, with 126 patients (77%) receiving at least one of these tests (Table 4).

Anticoagulant therapy was changed in 43 patients (26%) in the following ways: initiated in 35 patients (21%), transitioned to a different anticoagulant in 6 patients (4%), and discontinued in 2 patients (1%). Of the 35 patients initiating anticoagulant therapy, 29 had documented thrombosis (24 had VTE, 4 had cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [CVST], and 1 had basilar artery thrombosis). Overall, 2 instances were identified in which initiation of anticoagulant therapy at discharge was in response to thrombophilia test results. In the first instance, warfarin without a parenteral anticoagulant bridge was initiated for a 54-year-old patient with a cryptogenic stroke who tested positive for β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, and protein S deficiency. In the second instance, warfarin with an enoxaparin bridge was initiated for a 26-year-old patient with a cryptogenic stroke who tested positive for β2-glycoprotein 1 IgG and IgM antibodies, cardiolipin IgG antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, protein C deficiency, and antithrombin deficiency. Of the 163 patients receiving thrombophilia testing, only 2 patients (1%) had clear documentation of being offered genetic consultation.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis, 1451 thrombophilia tests were performed in 163 patients over 6 months. Tested patients were relatively young, which is likely explained by the number of patients tested for pregnancy-related conditions and the fact that a stroke or VTE in younger patients more frequently prompted providers to suspect thrombophilia. Nearly three-fourths of patients were female, which is likely due to testing for pregnancy-related conditions and possibly diagnostic suspicion bias given the comparative predilection of antiphospholipid syndrome for women. The patient characteristics in our study are consistent with other studies evaluating thrombophilia testing.21,22

Thrombophilia testing was most frequently prompted by stroke, VTE, and pregnancy-related conditions. Only 26% of patients had acute thrombosis identified during the admission, primarily because of the high proportion of tests for cryptogenic strokes and pregnancy-related conditions. Thrombophilia testing is recommended in patients who have had a stroke when the stroke is considered to be cryptogenic after a standard stroke evaluation.23 Thrombophilia testing in pregnancy-related conditions is controversial but is often considered in situations such as stillbirths with severe placental pathology and/or significant growth restriction, or in mothers with a personal or family history of thrombosis.24 The proportion of testing for pregnancy-related conditions may be greater than at other institutions because UUHC Maternal Fetal Medicine is a referral center for women with conditions associated with hypercoagulability. Anticoagulant therapy was initiated in 21% of patients, but specifically in response to thrombophilia testing in only 2 instances; in most cases, anticoagulant therapy was initiated regardless of thrombophilia test results.

The results of this study confirm our hypothesis because the majority of thrombophilia tests occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility. Testing in these situations was not isolated to specific patients or medical services because 77% of tested patients received at least 1 test associated with minimal clinical utility. Our study took a conservative approach in defining scenarios associated with minimal clinical utility because other situations can also affect testing accuracy (eg, hepatic disease, nephrotic syndrome) but were not included in our analysis of this outcome.

The results of this study highlight opportunities to improve thrombophilia testing practices at our institution and may be generalizable to institutions with similar testing patterns. Because multiple medical services order thrombophilia tests, strategies to improve testing practices are still being determined. The results of this study can serve as a baseline for comparison after strategies are implemented. The most common situation associated with minimal clinical utility was the use of test types not generally recommended by guidelines or UUHC Thrombosis Service physicians for thrombophilia testing (eg, β2-glycoprotein 1 IgA antibodies, phosphatidyl antibodies). We intend to require a hematology or thrombosis specialty consult prior to ordering these tests. This intervention alone could potentially decrease unnecessary testing by a third. Another consideration is to require a specialty consult prior to any inpatient thrombophilia testing. This strategy has been found to decrease inappropriate testing at other institutions.21 We also intend to streamline available thrombophilia testing panels because a poorly designed panel could lead to ordering of multiple tests associated with minimal clinical utility. At least 12 different thrombophilia panels are currently available in our computerized physician order entry system (see Supplementary Table 5). We hypothesize that current panel designs contribute to providers inadvertently ordering unintended or duplicate tests and that reducing the number of available panels and clearly delineating what tests are contained in each panel is likely to reduce unnecessary testing. Other strategies being considered include using electronic clinical decision support tools, implementing strict ordering criteria for all inpatient testing, and establishing a thrombosis stewardship program.

Our study was unique in at least 2 ways. First, previous studies describing thrombophilia testing have described testing patterns for patients with specific indications (eg, VTE), whereas our study described all thrombophilia tests regardless of indication. This allows for testing pattern comparisons across indications and medical services, increasing the generalizability of our results. Second, this study quantifies tests occurring in situations associated with a practical definition of minimal clinical utility.

Our study has several limitations: (1) Many variables were reliant on provider notes and other documentation, which allows for potential misclassification of variables. (2) It was not always possible to determine the ultimate utility of each test in clinical management decisions, and our study did not investigate the impact of thrombophilia testing on duration of anticoagulant therapy. Additionally, select situations could benefit from testing regardless if anticoagulant therapy is altered (eg, informing contraceptive choices). (3) Testing performed following a provoked acute thrombosis was defined as testing within 3 months following administratively defined major surgery. This definition could have included some minor procedures that do not substantially increase VTE risk, resulting in underestimated clinical utility. (4) The UUHC University Hospital serves as a referral hospital for a large geographical area, and investigators did not have access to outpatient records for a large proportion of discharged patients. As a result, frequency of repeat testing could not be assessed, possibly resulting in overestimated clinical utility. (5) In categorizing indications for testing, testing for CVST was subcategorized under testing for ischemic stroke based on presenting symptoms rather than on underlying pathophysiology. The rationale for this categorization is that patients with CVST were often tested based on presenting symptoms. Additionally, tests for CVST were ordered by the neurology service, which also ordered tests for all other ischemic stroke indications. (6) The purpose of our study was to investigate the subset of the hospital’s patient population that received thrombophilia testing, and patients were identified by tests received and not by diagnosis codes. As a result, we are unable to provide the proportion of total patients treated at the hospital for specific conditions who were tested (eg, the proportion of stroke patients that received thrombophilia testing). (7) Current practice guidelines do not recommend testing for phosphatidyl antibodies, even when traditional antiphospholipid testing is negative.25-27 Although expert panels continue to explore associations between phosphatidyl antibodies and pregnancy morbidity and thrombotic events, the low level of evidence is insufficient to guide clinical management.28 Therefore, we categorized all phosphatidyl testing as associated with minimal clinical utility.

CONCLUSIONS

In a large academic medical center, the majority of tests occurred in situations associated with minimal clinical utility. Strategies to improve thrombophilia testing practices are needed in order to minimize potentially inappropriate testing, provide more cost-effective care, and promote value-driven outcomes.

Disclosure

S.W. received financial support for this submitted work via a Bristol-Myers-Squibb grant. G.F. received financial support from Portola Pharmaceuticals for consulting and lectures that were not related to this submitted work.

1. Franco RF, Reitsma PH. Genetic risk factors of venous thrombosis. Hum Genet. 2001;109(4):369-384. PubMed

2. Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Lindpaintner K, Stampfer MJ, Eisenberg PR, Miletich JP. Mutation in the gene coding for coagulation factor V and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thrombosis in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):912-917. PubMed

3. Koster T, Rosendaal FR, de Ronde H, Briët E, Vandenbroucke JP, Bertina RM. Venous thrombosis due to poor anticoagulant response to activated protein C: Leiden Thrombophilia Study. Lancet. 1993;342(8886-8887):1503-1506. PubMed

4. Margaglione M, Brancaccio V, Giuliani N, et al. Increased risk for venous thrombosis in carriers of the prothrombin G-->A20210 gene variant. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(2):89-93. PubMed

5. De Stefano V, Martinelli I, Mannucci PM, et al. The risk of recurrent deep venous thrombosis among heterozygous carriers of both factor V Leiden and the G20210A prothrombin mutation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:801-806. PubMed

6. Dickey TL. Can thrombophilia testing help to prevent recurrent VTE? Part 2. JAAPA. 2002;15(12):23-24, 27-29. PubMed

7. Simpson EL, Stevenson MD, Rawdin A, Papaioannou D. Thrombophilia testing in people with venous thromboembolism: systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(2):iii, ix-x, 1-91. PubMed

8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Venous thromboembolic disease: the management of venous thromboembolic diseases and the role of thrombophilia testing. NICE clinical guideline 144. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg144. Accessed on June 30, 2017.

9. Evalution of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: routine testing for factor V Leiden (R506Q) and prothrombin (20210G>A) mutations in adults with a history of idiopathic venous thromboembolism and their adult family members. Genet Med. 2011;13(1):67-76.

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-494S. PubMed

11. Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220. PubMed

12. Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely® campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:9-14. PubMed

13. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):154-164. PubMed

14. Christiansen SC, Cannegieter SC, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Thrombophilia, clinical factors, and recurrent venous thrombotic events. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2352-2361. PubMed

15. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, et al. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(1):1-7. PubMed

16. Miles JS, Miletich JP, Goldhaber SZ, Hennekens CH, Ridker PM. G20210A mutation in the prothrombin gene and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(1):215-218. PubMed

17. Eichinger S, Weltermann A, Mannhalter C, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in heterozygous carriers of factor V Leiden and a first spontaneous venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2357-2360. PubMed

18. Mazzolai L, Duchosal MA. Hereditary thrombophilia and venous thromboembolism: critical evaluation of the clinical implications of screening. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34(4):483-488. PubMed

19. Merriman L, Greaves M. Testing for thrombophilia: an evidence‐based approach. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(973):699-704. PubMed

20. Favaloro EJ, McDonald D, Lippi G. Laboratory investigation of thrombophilia: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35(7):695-710. PubMed

21. Shen YM, Tsai J, Taiwo E, et al. Analysis of thrombophilia test ordering practices at an academic center: a proposal for appropriate testing to reduce harm and cost. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155326. PubMed

22. Meyer MR, Witt DM, Delate T, et al. Thrombophilia testing patterns amongst patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2015;136(6):1160-1164. PubMed

23. Saver JL. Clinical practice: cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2065-2074. PubMed

24. ACOG practice bulletin no. 102: management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):748-761. PubMed

25. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):295-306. PubMed

26. Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW, Greer IA, Greaves M, British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2012;157(1):47-58. PubMed

27. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 132: antiphospholipid syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1514-1521. PubMed

28. Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Andreoli L, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force. Report on antiphospholipid syndrome laboratory diagnostics and trends. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(9):917-930. PubMed

1. Franco RF, Reitsma PH. Genetic risk factors of venous thrombosis. Hum Genet. 2001;109(4):369-384. PubMed

2. Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Lindpaintner K, Stampfer MJ, Eisenberg PR, Miletich JP. Mutation in the gene coding for coagulation factor V and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thrombosis in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):912-917. PubMed

3. Koster T, Rosendaal FR, de Ronde H, Briët E, Vandenbroucke JP, Bertina RM. Venous thrombosis due to poor anticoagulant response to activated protein C: Leiden Thrombophilia Study. Lancet. 1993;342(8886-8887):1503-1506. PubMed

4. Margaglione M, Brancaccio V, Giuliani N, et al. Increased risk for venous thrombosis in carriers of the prothrombin G-->A20210 gene variant. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(2):89-93. PubMed

5. De Stefano V, Martinelli I, Mannucci PM, et al. The risk of recurrent deep venous thrombosis among heterozygous carriers of both factor V Leiden and the G20210A prothrombin mutation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:801-806. PubMed

6. Dickey TL. Can thrombophilia testing help to prevent recurrent VTE? Part 2. JAAPA. 2002;15(12):23-24, 27-29. PubMed

7. Simpson EL, Stevenson MD, Rawdin A, Papaioannou D. Thrombophilia testing in people with venous thromboembolism: systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(2):iii, ix-x, 1-91. PubMed

8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Venous thromboembolic disease: the management of venous thromboembolic diseases and the role of thrombophilia testing. NICE clinical guideline 144. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg144. Accessed on June 30, 2017.

9. Evalution of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: routine testing for factor V Leiden (R506Q) and prothrombin (20210G>A) mutations in adults with a history of idiopathic venous thromboembolism and their adult family members. Genet Med. 2011;13(1):67-76.

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-494S. PubMed

11. Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220. PubMed

12. Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely® campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:9-14. PubMed

13. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):154-164. PubMed

14. Christiansen SC, Cannegieter SC, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Thrombophilia, clinical factors, and recurrent venous thrombotic events. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2352-2361. PubMed

15. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, et al. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(1):1-7. PubMed

16. Miles JS, Miletich JP, Goldhaber SZ, Hennekens CH, Ridker PM. G20210A mutation in the prothrombin gene and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(1):215-218. PubMed

17. Eichinger S, Weltermann A, Mannhalter C, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in heterozygous carriers of factor V Leiden and a first spontaneous venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2357-2360. PubMed

18. Mazzolai L, Duchosal MA. Hereditary thrombophilia and venous thromboembolism: critical evaluation of the clinical implications of screening. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34(4):483-488. PubMed

19. Merriman L, Greaves M. Testing for thrombophilia: an evidence‐based approach. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(973):699-704. PubMed

20. Favaloro EJ, McDonald D, Lippi G. Laboratory investigation of thrombophilia: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35(7):695-710. PubMed

21. Shen YM, Tsai J, Taiwo E, et al. Analysis of thrombophilia test ordering practices at an academic center: a proposal for appropriate testing to reduce harm and cost. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155326. PubMed

22. Meyer MR, Witt DM, Delate T, et al. Thrombophilia testing patterns amongst patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2015;136(6):1160-1164. PubMed

23. Saver JL. Clinical practice: cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2065-2074. PubMed

24. ACOG practice bulletin no. 102: management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):748-761. PubMed

25. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):295-306. PubMed

26. Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW, Greer IA, Greaves M, British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2012;157(1):47-58. PubMed

27. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 132: antiphospholipid syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1514-1521. PubMed

28. Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Andreoli L, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force. Report on antiphospholipid syndrome laboratory diagnostics and trends. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(9):917-930. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine