User login

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

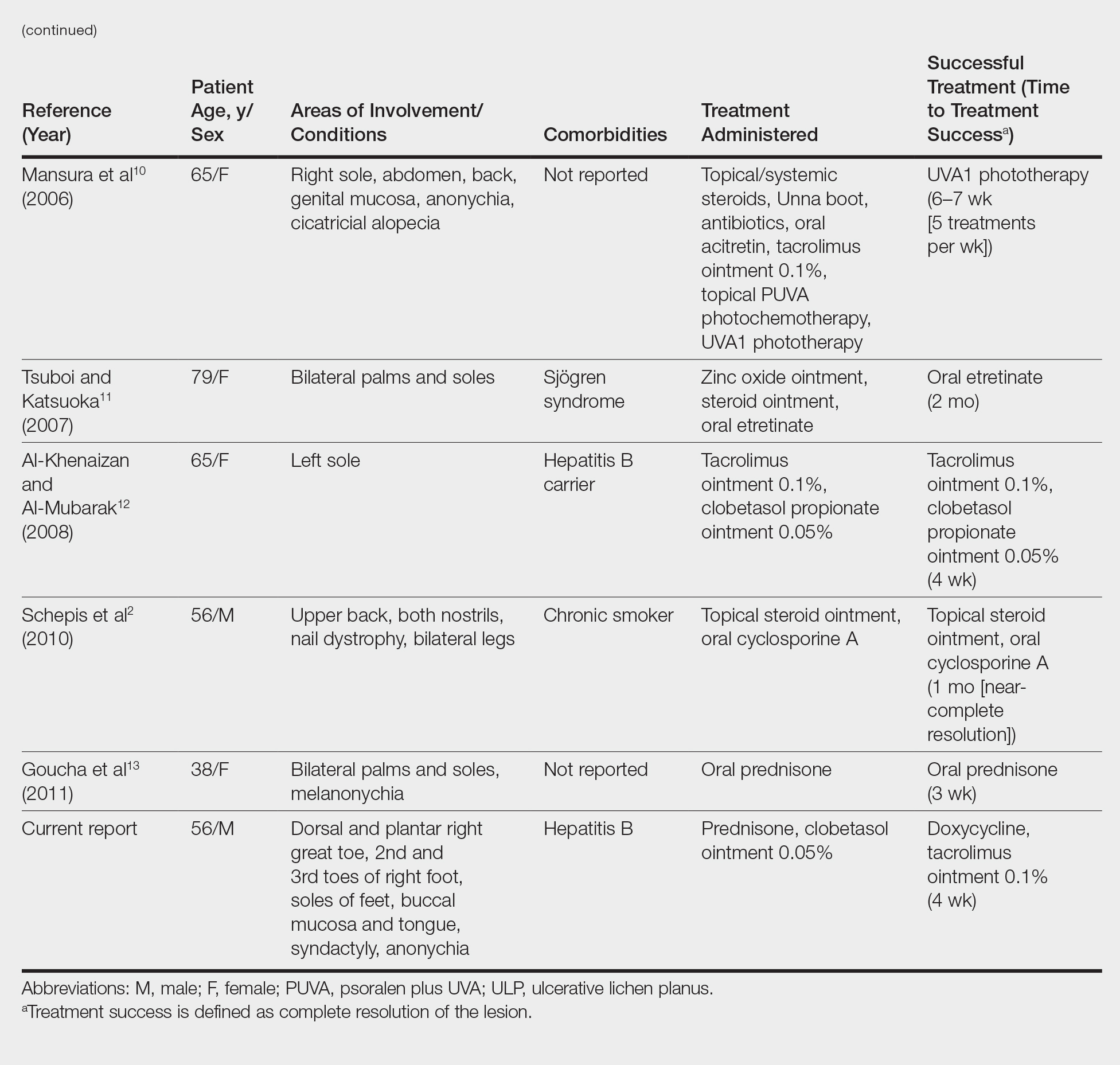

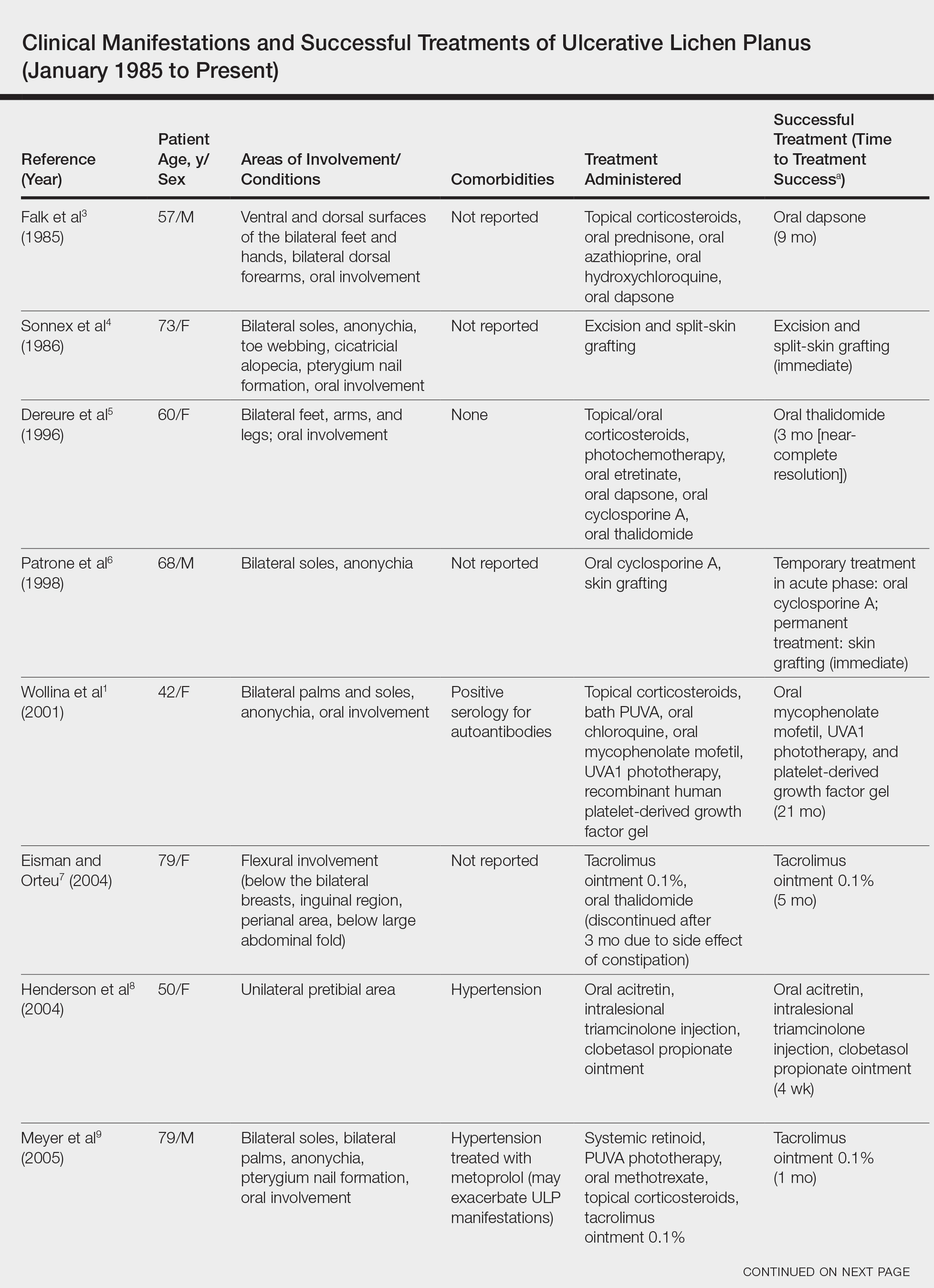

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

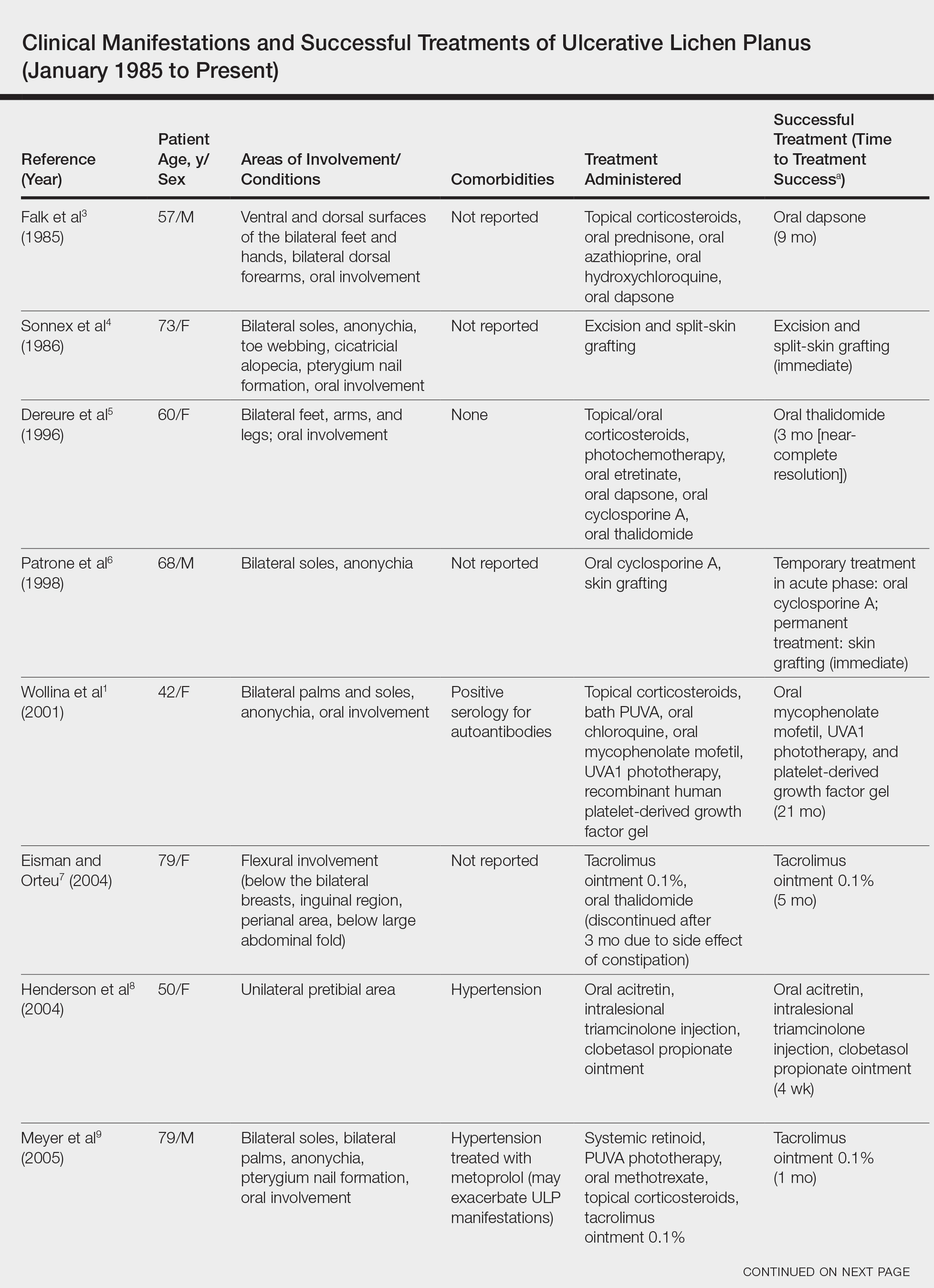

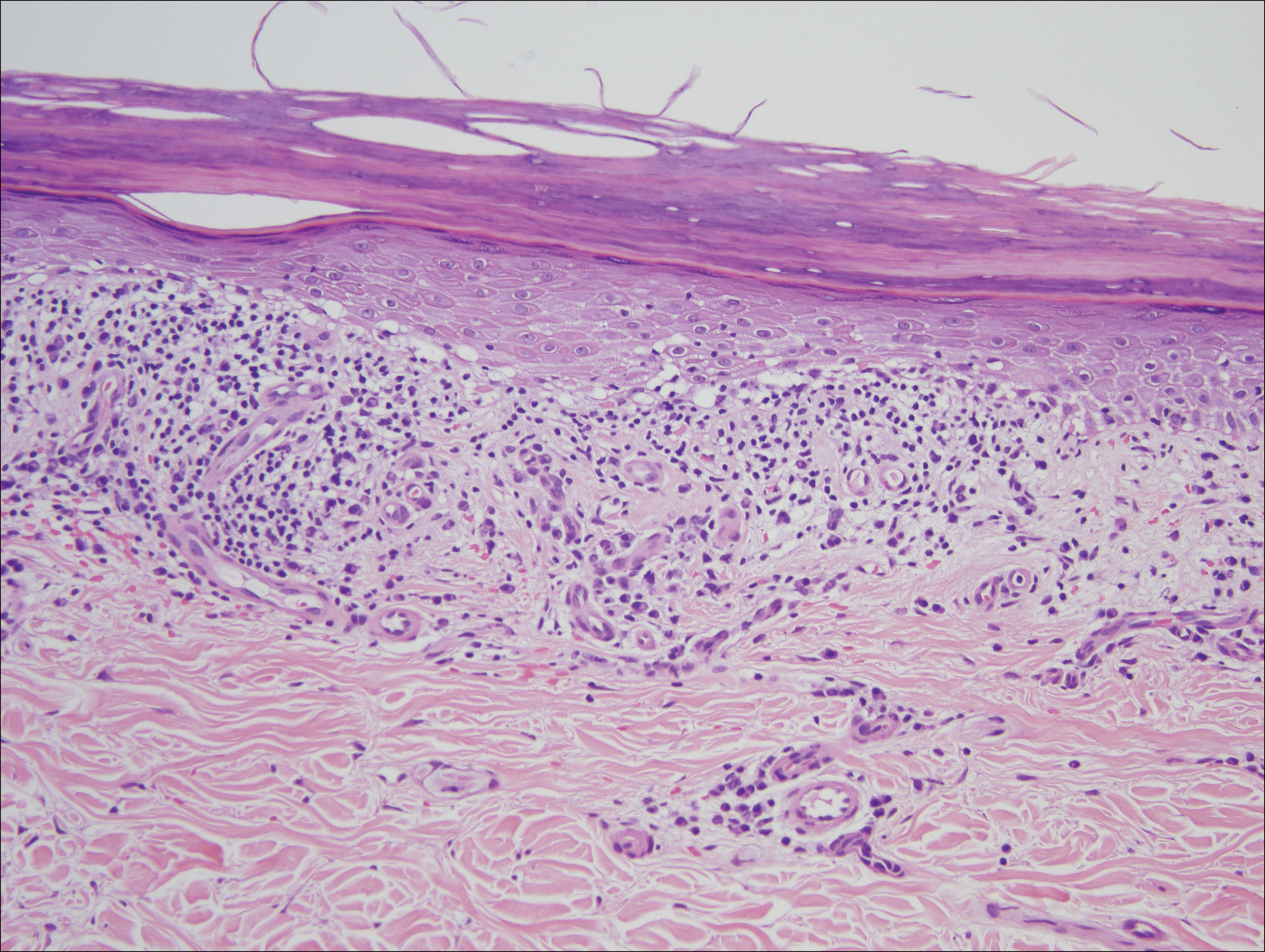

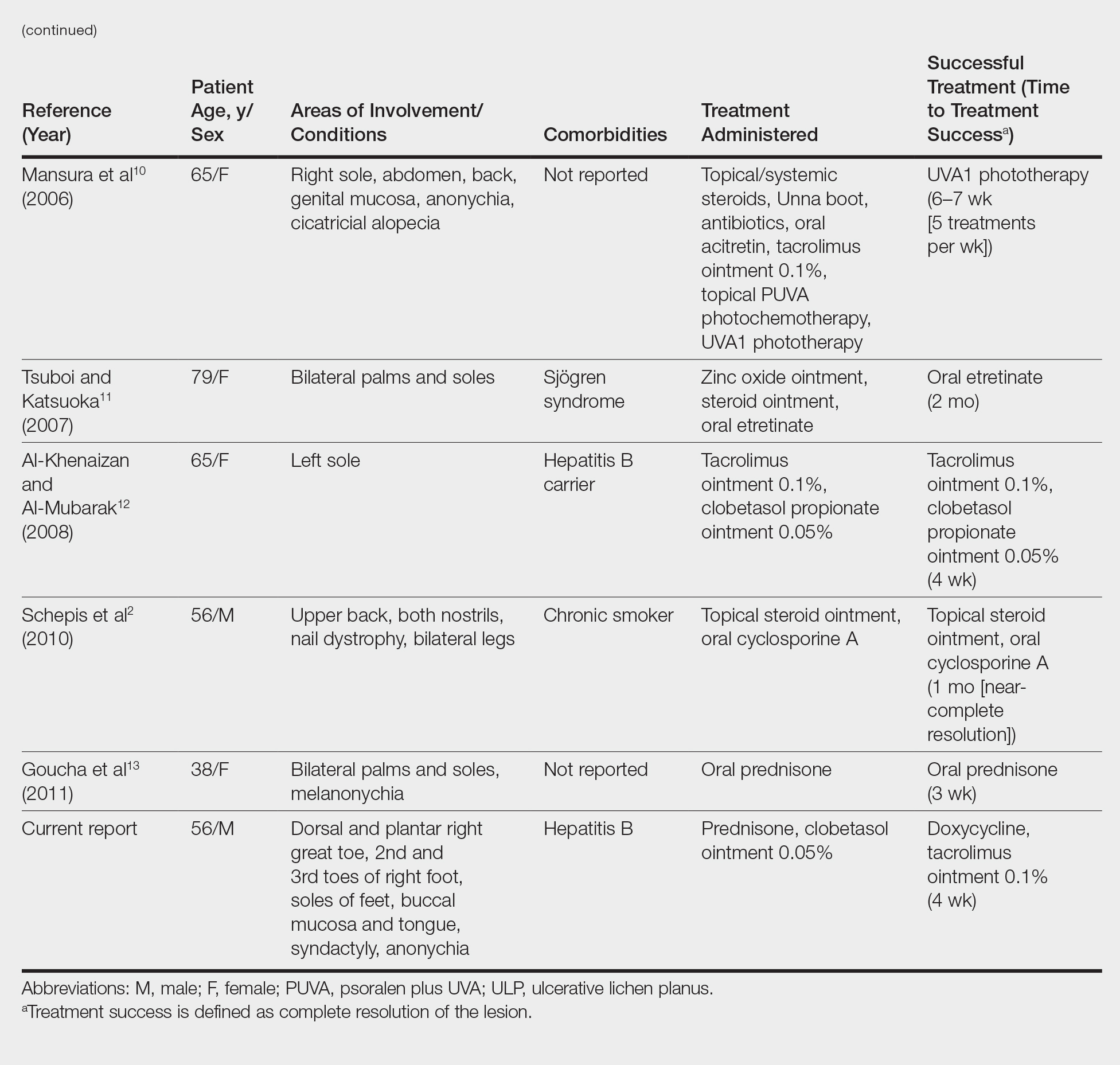

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

Practice Points

- Consider ulcerative lichen planus (ULP) for chronic wounds on the soles.

- Topical therapeutic options may present a rapidly effective and relatively safe alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term management of plantar ULP.