User login

Infectious diseases are the most common reason for rehospitalization among patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI), regardless of the number of years postinjury.1 The appropriate use and selection of antibiotics for properly diagnosed infectious diseases is especially important for this population. This principle helps to avoid the development of drug-resistant organisms and reduces the risk of recurrent infections, aligning with antibiotic stewardship.

Antibiotics are the most common class of drug allergies in the general population, and penicillin is the most frequently reported allergen (up to 10%).2 Prescription drug–induced anaphylaxis is severe and life threatening with a reported frequency of 1.1%. Penicillin and sulfonamide (46 and 15 per 10,000 patients, respectively) are the most common allergens.3 Although there is a significant difference between an adverse drug reaction (ADR) and true hypersensitivity, once documented in the electronic health record (EHR) as an allergy, this information deters use of the listed drugs.

Genitourinary, skin, and respiratory diseases are the leading causes for rehospitalization in patients with SCI.1 A large proportion of these are infectious in etiology and require antibiotic treatment. In fact, persons with SCI are at high risk for antibiotic overuse and hospital-acquired infection due to chronic bacteriuria, frequent health care exposure, implanted medical devices, and other factors.4 Concurrently, there is a crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria proliferation, described as a threat to patient safety and public health.5,6 Its severity is illustrated by the report that 38% of the cultures from patients with spinal cord injury are multidrug resistant gram-negative organisms.7

The SCI center at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, serves a high concentration of active-duty military members and veterans with SCI. A study that reviews the exact frequency of antibiotic drug allergies listed on the EHR would be a key first step to identify the magnitude of this issue. The results could guide investigation into differentiating true allergies from ADRs, thereby widening the options for potentially life-saving antibiotic treatment.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients included in the local SCI registry between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We collected data on patient demographics (age, sex, race and ethnicity) and a description of patients’ injuries (International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury [ISNCSCI] and etiology of injury [traumatic vs atraumatic]). The outcomes included antibiotic allergy and ADRs.

In the EHR, allergies can be listed toward an antibiotic class or a specific antibiotic. An allergy to each specific antibiotic would be recorded separately; however, overlap among antibiotic classes was not duplicated. For example, if a subject has a listed antibiotic allergy to ceftriaxone and cefepime with listed reactions, we would record allergies to each of these antibiotics but would only report a single allergy to the cephalosporin subclass.

Since we did not differentiate hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) from other ADRs, the reported reactions were grouped by signs and symptoms. There is a variety of terms used to report similar reactions, and best efforts were made to record the data as accurately as possible. Patient-reported history for risk stratification is a tool we used to group these historical reactions into high- vs low-risk for severe reactions. High-risk signs are those listed as anaphylaxis; anaphylactic reactions; angioedema presenting as swelling of mouth, eyes, lips, or tongue; blisters or ulcers involving the lips, mouth, eyes, urethra, vagina, or peeling skin; respiratory changes; shortness of breath; dyspnea; hypotension; or organ involvement (kidneys, lungs, liver).6

Inclusion criteria were all veterans who were diagnosed with tetraplegia or paraplegia and received annual evaluation between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We chose this period because it was the beginning of a financial year at the JAHVH SCI department using the SCI registry. The SCI annual evaluation is a routine practitioner encounter with the veteran, along with appropriate laboratory testing and imaging to follow up potential chronic health issues specific to patients with SCI. Annual evaluations provide an opportunity to maintain routine health screening and preventive care. Patients who had significant portions of data missing or missing elements of primary outcomes were excluded from analysis. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (VA IRBNet #1573370-4 on September 9, 2019).

Results

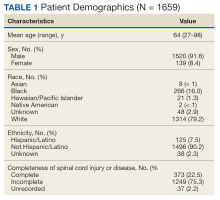

Of 1866 patients reviewed, 207 (11.1%) were excluded due to missing data, resulting in 1659 records that were analyzed. Mean age was 64 years, and male to female ratio was about 10 to 1. Most of the SCI or diseases were classified as incomplete (n = 1249) per ISNCSCI (absence of sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments) compared with 373 classified as complete.

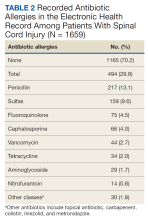

Of the 1659 patients, 494 (29.8%) had a recorded allergy to antibiotics. The most frequently recorded were 217 penicillin (13.1%), 159 sulfa drugs (9.6%), 75 fluoroquinolone (4.5%), 66 cephalosporin (4.0%), and 44 vancomycin (2.7%) allergies.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the frequency and characteristics of antibiotic allergies at a single SCI center to better identify potential areas for quality improvement when recording drug allergies. A study in the general population used self-reported methods to collect such information found about a 15% prevalence of antibiotic allergy, which was lower than the 29.8% prevalence noted in our study.8

Regarding the most common antibiotic allergies, one study reported allergy to penicillin in the EHR in 12.8% of patients at a major US regional health care system, while 13.1% of patients with SCI had documented allergy to penicillin in our study.9 Regarding the other antibiotic classes, the percentage of allergies were higher than those reported in the general population: sulfonamide (9.6% vs 7.4%), fluoroquinolones (4.5% vs 1.3%), and cephalosporins (4.0% vs 1.7%).10 The EHR appears to capture a much higher rate of antibiotic allergies than that in self-reported studies, such as a study of self-reported allergy in the general adult population in Portugal, where only 4.5% of patients reported allergy to any β-lactam medications.10

The prevalence of an antibiotic allergy could be affected by the health care setting and sex distribution. For example, the Zhou and colleagues’ study conducted in the Greater Boston area showed higher reported antibiotic rates than those in a study from a Southern California medical group. The higher proportion of tertiary referral patients in that specific network was suggested to be the cause of the difference.8,9 Our results in the SCI population are more comparable to that in a tertiary setting. This is consistent with the fact that persons with SCI generally have more exposure to antibiotics and consequently a higher reported rate of allergic reactions to antibiotics.

Similarly, the same study in Southern California noted that female patients use more antibiotics than do male patients, thus potentially contributing to higher rates of reported allergy toward all classes of antibiotics.8 Our study did not investigate antibiotic allergy by sex; however, the significantly higher proportion of male sex among the veteran population would have impacted these results.

Limitations

Our study was limited as a single-center retrospective study. However, our center is one of the major SCI specialty hubs, and the results should be somewhat reflective of those in the veterans with SCI population. Veterans under the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical care have the option to seek care or procedures in non-VA facilities. If allergies to antibiotics occurred outside of the VA system, there is no mechanism to automatically merge with the VA EHR allergy list, unless they are later recorded and added to the VA EHR. Thus, there is potential for underreporting.

Drug anaphylaxis incidence was noted to change over time.4,8,9 For example, a downtrend of reported antibiotic allergy was reported between 1990 and 2013.10 Our study only reflects an overall prevalence of a single cohort, without demonstration of relationship to time.

Lastly, this study did not aim to differentiate HSRs from other ADRs. This is exactly the point of the study, which investigated the frequency of EHR-recorded antibiotic allergies in our SCI population and reflects the issue with indiscriminate recording of ADRs and HSRs under the umbrella of allergy in the EHR. Further diagnosing true allergies should be considered in the SCI population after weighing the risks and benefits of assessment, aligning with the wishes of the veteran, obtaining informed consent, and addressing the cost-effectiveness of specific tests. We suggest that primary care practitioners work closely with allergy specialists to formulate a mechanism to diagnose various antibiotic allergic reactions, including serum tryptase, epicutaneous skin testing, intradermal skin testing, patch testing, delayed intradermal testing, and drug challenge as appropriate. It is also possible that in cases where very mild reactions/adverse effects of antibiotics were recorded in the EHR, the clinicians and veterans may discuss reintroducing the same antibiotics or proceeding with further testing if necessary. In contrast, the 12% of those with a high risk of severe allergic reactions to penicillin in our study would benefit from allergist evaluation and access to epinephrine auto-injectors at all times. Differentiating true allergy is the only clear way to deter unnecessary avoidance of first-line therapies for antibiotic treatment and avoid promotion of antibiotic resistance.

Future studies can analyze antibiotic allergy based on demographics, including sex and age difference, as well as exploring outpatient vs inpatient settings. Aside from prevalence, we hope to demonstrate antibiotic allergy over time, especially after integration of diagnostic allergy testing, to evaluate the impact to EHR-recorded allergies.

Conclusions

Almost 30% of patients with SCI had a recorded allergy to at least 1 antibiotic. The most common allergy was to penicillin, which is similar to what has previously been reported for the general adult US population. However, only 12% of those with a penicillin allergy were considered high risk of true allergic reactions. Consequently, there are opportunities to examine whether approaches to confirm true reactions (such as skin testing) would help to mitigate unnecessary avoidance of certain antibiotic classes due to mild ADRs, rather than a true allergy, in persons with SCI. This would be an important effort to combat both individual safety concerns and the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance. Given the available evidence, it is reasonable for SCI health care practitioners to discuss the potential risks and benefits of allergy testing with patients with SCI; this maintains a patient-centered approach that can ensure judicious use of antibiotics when necessary.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported (or supported in part) with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital

References

1. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems. 2016 Annual Report –Complete Public Version. University of Alabama at Birmingham. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/2016%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf

2. Macy E, Richter PK, Falkoff R, Zeiger R. Skin testing with penicilloate and penilloate prepared by an improved method: amoxicillin oral challenge in patients with negative skin test responses to penicillin reagents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(5):586-591. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70159-3 3. Dhopeshwarkar N, Sheikh A, Doan R, et al. Drug-induced anaphylaxis documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.010

4. Evans CT, LaVela SL, Weaver FM, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(3):234-242. doi:10.1086/527509

5. Evans CT, Jump RL, Krein SL, et al. Setting a research agenda in prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) outside of acute care settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(2):210-213. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.291

6. Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phllips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183-198. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 7. Evans CT, Fitzpatrick MA, Jones MM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms in patients with spinal cord injury. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(12):1464-1471. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.238 8. Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

9. Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

10. Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praça F, Gomes L, Mariño E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(10):1597-1601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02070.x

Infectious diseases are the most common reason for rehospitalization among patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI), regardless of the number of years postinjury.1 The appropriate use and selection of antibiotics for properly diagnosed infectious diseases is especially important for this population. This principle helps to avoid the development of drug-resistant organisms and reduces the risk of recurrent infections, aligning with antibiotic stewardship.

Antibiotics are the most common class of drug allergies in the general population, and penicillin is the most frequently reported allergen (up to 10%).2 Prescription drug–induced anaphylaxis is severe and life threatening with a reported frequency of 1.1%. Penicillin and sulfonamide (46 and 15 per 10,000 patients, respectively) are the most common allergens.3 Although there is a significant difference between an adverse drug reaction (ADR) and true hypersensitivity, once documented in the electronic health record (EHR) as an allergy, this information deters use of the listed drugs.

Genitourinary, skin, and respiratory diseases are the leading causes for rehospitalization in patients with SCI.1 A large proportion of these are infectious in etiology and require antibiotic treatment. In fact, persons with SCI are at high risk for antibiotic overuse and hospital-acquired infection due to chronic bacteriuria, frequent health care exposure, implanted medical devices, and other factors.4 Concurrently, there is a crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria proliferation, described as a threat to patient safety and public health.5,6 Its severity is illustrated by the report that 38% of the cultures from patients with spinal cord injury are multidrug resistant gram-negative organisms.7

The SCI center at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, serves a high concentration of active-duty military members and veterans with SCI. A study that reviews the exact frequency of antibiotic drug allergies listed on the EHR would be a key first step to identify the magnitude of this issue. The results could guide investigation into differentiating true allergies from ADRs, thereby widening the options for potentially life-saving antibiotic treatment.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients included in the local SCI registry between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We collected data on patient demographics (age, sex, race and ethnicity) and a description of patients’ injuries (International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury [ISNCSCI] and etiology of injury [traumatic vs atraumatic]). The outcomes included antibiotic allergy and ADRs.

In the EHR, allergies can be listed toward an antibiotic class or a specific antibiotic. An allergy to each specific antibiotic would be recorded separately; however, overlap among antibiotic classes was not duplicated. For example, if a subject has a listed antibiotic allergy to ceftriaxone and cefepime with listed reactions, we would record allergies to each of these antibiotics but would only report a single allergy to the cephalosporin subclass.

Since we did not differentiate hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) from other ADRs, the reported reactions were grouped by signs and symptoms. There is a variety of terms used to report similar reactions, and best efforts were made to record the data as accurately as possible. Patient-reported history for risk stratification is a tool we used to group these historical reactions into high- vs low-risk for severe reactions. High-risk signs are those listed as anaphylaxis; anaphylactic reactions; angioedema presenting as swelling of mouth, eyes, lips, or tongue; blisters or ulcers involving the lips, mouth, eyes, urethra, vagina, or peeling skin; respiratory changes; shortness of breath; dyspnea; hypotension; or organ involvement (kidneys, lungs, liver).6

Inclusion criteria were all veterans who were diagnosed with tetraplegia or paraplegia and received annual evaluation between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We chose this period because it was the beginning of a financial year at the JAHVH SCI department using the SCI registry. The SCI annual evaluation is a routine practitioner encounter with the veteran, along with appropriate laboratory testing and imaging to follow up potential chronic health issues specific to patients with SCI. Annual evaluations provide an opportunity to maintain routine health screening and preventive care. Patients who had significant portions of data missing or missing elements of primary outcomes were excluded from analysis. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (VA IRBNet #1573370-4 on September 9, 2019).

Results

Of 1866 patients reviewed, 207 (11.1%) were excluded due to missing data, resulting in 1659 records that were analyzed. Mean age was 64 years, and male to female ratio was about 10 to 1. Most of the SCI or diseases were classified as incomplete (n = 1249) per ISNCSCI (absence of sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments) compared with 373 classified as complete.

Of the 1659 patients, 494 (29.8%) had a recorded allergy to antibiotics. The most frequently recorded were 217 penicillin (13.1%), 159 sulfa drugs (9.6%), 75 fluoroquinolone (4.5%), 66 cephalosporin (4.0%), and 44 vancomycin (2.7%) allergies.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the frequency and characteristics of antibiotic allergies at a single SCI center to better identify potential areas for quality improvement when recording drug allergies. A study in the general population used self-reported methods to collect such information found about a 15% prevalence of antibiotic allergy, which was lower than the 29.8% prevalence noted in our study.8

Regarding the most common antibiotic allergies, one study reported allergy to penicillin in the EHR in 12.8% of patients at a major US regional health care system, while 13.1% of patients with SCI had documented allergy to penicillin in our study.9 Regarding the other antibiotic classes, the percentage of allergies were higher than those reported in the general population: sulfonamide (9.6% vs 7.4%), fluoroquinolones (4.5% vs 1.3%), and cephalosporins (4.0% vs 1.7%).10 The EHR appears to capture a much higher rate of antibiotic allergies than that in self-reported studies, such as a study of self-reported allergy in the general adult population in Portugal, where only 4.5% of patients reported allergy to any β-lactam medications.10

The prevalence of an antibiotic allergy could be affected by the health care setting and sex distribution. For example, the Zhou and colleagues’ study conducted in the Greater Boston area showed higher reported antibiotic rates than those in a study from a Southern California medical group. The higher proportion of tertiary referral patients in that specific network was suggested to be the cause of the difference.8,9 Our results in the SCI population are more comparable to that in a tertiary setting. This is consistent with the fact that persons with SCI generally have more exposure to antibiotics and consequently a higher reported rate of allergic reactions to antibiotics.

Similarly, the same study in Southern California noted that female patients use more antibiotics than do male patients, thus potentially contributing to higher rates of reported allergy toward all classes of antibiotics.8 Our study did not investigate antibiotic allergy by sex; however, the significantly higher proportion of male sex among the veteran population would have impacted these results.

Limitations

Our study was limited as a single-center retrospective study. However, our center is one of the major SCI specialty hubs, and the results should be somewhat reflective of those in the veterans with SCI population. Veterans under the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical care have the option to seek care or procedures in non-VA facilities. If allergies to antibiotics occurred outside of the VA system, there is no mechanism to automatically merge with the VA EHR allergy list, unless they are later recorded and added to the VA EHR. Thus, there is potential for underreporting.

Drug anaphylaxis incidence was noted to change over time.4,8,9 For example, a downtrend of reported antibiotic allergy was reported between 1990 and 2013.10 Our study only reflects an overall prevalence of a single cohort, without demonstration of relationship to time.

Lastly, this study did not aim to differentiate HSRs from other ADRs. This is exactly the point of the study, which investigated the frequency of EHR-recorded antibiotic allergies in our SCI population and reflects the issue with indiscriminate recording of ADRs and HSRs under the umbrella of allergy in the EHR. Further diagnosing true allergies should be considered in the SCI population after weighing the risks and benefits of assessment, aligning with the wishes of the veteran, obtaining informed consent, and addressing the cost-effectiveness of specific tests. We suggest that primary care practitioners work closely with allergy specialists to formulate a mechanism to diagnose various antibiotic allergic reactions, including serum tryptase, epicutaneous skin testing, intradermal skin testing, patch testing, delayed intradermal testing, and drug challenge as appropriate. It is also possible that in cases where very mild reactions/adverse effects of antibiotics were recorded in the EHR, the clinicians and veterans may discuss reintroducing the same antibiotics or proceeding with further testing if necessary. In contrast, the 12% of those with a high risk of severe allergic reactions to penicillin in our study would benefit from allergist evaluation and access to epinephrine auto-injectors at all times. Differentiating true allergy is the only clear way to deter unnecessary avoidance of first-line therapies for antibiotic treatment and avoid promotion of antibiotic resistance.

Future studies can analyze antibiotic allergy based on demographics, including sex and age difference, as well as exploring outpatient vs inpatient settings. Aside from prevalence, we hope to demonstrate antibiotic allergy over time, especially after integration of diagnostic allergy testing, to evaluate the impact to EHR-recorded allergies.

Conclusions

Almost 30% of patients with SCI had a recorded allergy to at least 1 antibiotic. The most common allergy was to penicillin, which is similar to what has previously been reported for the general adult US population. However, only 12% of those with a penicillin allergy were considered high risk of true allergic reactions. Consequently, there are opportunities to examine whether approaches to confirm true reactions (such as skin testing) would help to mitigate unnecessary avoidance of certain antibiotic classes due to mild ADRs, rather than a true allergy, in persons with SCI. This would be an important effort to combat both individual safety concerns and the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance. Given the available evidence, it is reasonable for SCI health care practitioners to discuss the potential risks and benefits of allergy testing with patients with SCI; this maintains a patient-centered approach that can ensure judicious use of antibiotics when necessary.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported (or supported in part) with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital

Infectious diseases are the most common reason for rehospitalization among patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI), regardless of the number of years postinjury.1 The appropriate use and selection of antibiotics for properly diagnosed infectious diseases is especially important for this population. This principle helps to avoid the development of drug-resistant organisms and reduces the risk of recurrent infections, aligning with antibiotic stewardship.

Antibiotics are the most common class of drug allergies in the general population, and penicillin is the most frequently reported allergen (up to 10%).2 Prescription drug–induced anaphylaxis is severe and life threatening with a reported frequency of 1.1%. Penicillin and sulfonamide (46 and 15 per 10,000 patients, respectively) are the most common allergens.3 Although there is a significant difference between an adverse drug reaction (ADR) and true hypersensitivity, once documented in the electronic health record (EHR) as an allergy, this information deters use of the listed drugs.

Genitourinary, skin, and respiratory diseases are the leading causes for rehospitalization in patients with SCI.1 A large proportion of these are infectious in etiology and require antibiotic treatment. In fact, persons with SCI are at high risk for antibiotic overuse and hospital-acquired infection due to chronic bacteriuria, frequent health care exposure, implanted medical devices, and other factors.4 Concurrently, there is a crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria proliferation, described as a threat to patient safety and public health.5,6 Its severity is illustrated by the report that 38% of the cultures from patients with spinal cord injury are multidrug resistant gram-negative organisms.7

The SCI center at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, serves a high concentration of active-duty military members and veterans with SCI. A study that reviews the exact frequency of antibiotic drug allergies listed on the EHR would be a key first step to identify the magnitude of this issue. The results could guide investigation into differentiating true allergies from ADRs, thereby widening the options for potentially life-saving antibiotic treatment.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients included in the local SCI registry between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We collected data on patient demographics (age, sex, race and ethnicity) and a description of patients’ injuries (International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury [ISNCSCI] and etiology of injury [traumatic vs atraumatic]). The outcomes included antibiotic allergy and ADRs.

In the EHR, allergies can be listed toward an antibiotic class or a specific antibiotic. An allergy to each specific antibiotic would be recorded separately; however, overlap among antibiotic classes was not duplicated. For example, if a subject has a listed antibiotic allergy to ceftriaxone and cefepime with listed reactions, we would record allergies to each of these antibiotics but would only report a single allergy to the cephalosporin subclass.

Since we did not differentiate hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) from other ADRs, the reported reactions were grouped by signs and symptoms. There is a variety of terms used to report similar reactions, and best efforts were made to record the data as accurately as possible. Patient-reported history for risk stratification is a tool we used to group these historical reactions into high- vs low-risk for severe reactions. High-risk signs are those listed as anaphylaxis; anaphylactic reactions; angioedema presenting as swelling of mouth, eyes, lips, or tongue; blisters or ulcers involving the lips, mouth, eyes, urethra, vagina, or peeling skin; respiratory changes; shortness of breath; dyspnea; hypotension; or organ involvement (kidneys, lungs, liver).6

Inclusion criteria were all veterans who were diagnosed with tetraplegia or paraplegia and received annual evaluation between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We chose this period because it was the beginning of a financial year at the JAHVH SCI department using the SCI registry. The SCI annual evaluation is a routine practitioner encounter with the veteran, along with appropriate laboratory testing and imaging to follow up potential chronic health issues specific to patients with SCI. Annual evaluations provide an opportunity to maintain routine health screening and preventive care. Patients who had significant portions of data missing or missing elements of primary outcomes were excluded from analysis. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (VA IRBNet #1573370-4 on September 9, 2019).

Results

Of 1866 patients reviewed, 207 (11.1%) were excluded due to missing data, resulting in 1659 records that were analyzed. Mean age was 64 years, and male to female ratio was about 10 to 1. Most of the SCI or diseases were classified as incomplete (n = 1249) per ISNCSCI (absence of sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments) compared with 373 classified as complete.

Of the 1659 patients, 494 (29.8%) had a recorded allergy to antibiotics. The most frequently recorded were 217 penicillin (13.1%), 159 sulfa drugs (9.6%), 75 fluoroquinolone (4.5%), 66 cephalosporin (4.0%), and 44 vancomycin (2.7%) allergies.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the frequency and characteristics of antibiotic allergies at a single SCI center to better identify potential areas for quality improvement when recording drug allergies. A study in the general population used self-reported methods to collect such information found about a 15% prevalence of antibiotic allergy, which was lower than the 29.8% prevalence noted in our study.8

Regarding the most common antibiotic allergies, one study reported allergy to penicillin in the EHR in 12.8% of patients at a major US regional health care system, while 13.1% of patients with SCI had documented allergy to penicillin in our study.9 Regarding the other antibiotic classes, the percentage of allergies were higher than those reported in the general population: sulfonamide (9.6% vs 7.4%), fluoroquinolones (4.5% vs 1.3%), and cephalosporins (4.0% vs 1.7%).10 The EHR appears to capture a much higher rate of antibiotic allergies than that in self-reported studies, such as a study of self-reported allergy in the general adult population in Portugal, where only 4.5% of patients reported allergy to any β-lactam medications.10

The prevalence of an antibiotic allergy could be affected by the health care setting and sex distribution. For example, the Zhou and colleagues’ study conducted in the Greater Boston area showed higher reported antibiotic rates than those in a study from a Southern California medical group. The higher proportion of tertiary referral patients in that specific network was suggested to be the cause of the difference.8,9 Our results in the SCI population are more comparable to that in a tertiary setting. This is consistent with the fact that persons with SCI generally have more exposure to antibiotics and consequently a higher reported rate of allergic reactions to antibiotics.

Similarly, the same study in Southern California noted that female patients use more antibiotics than do male patients, thus potentially contributing to higher rates of reported allergy toward all classes of antibiotics.8 Our study did not investigate antibiotic allergy by sex; however, the significantly higher proportion of male sex among the veteran population would have impacted these results.

Limitations

Our study was limited as a single-center retrospective study. However, our center is one of the major SCI specialty hubs, and the results should be somewhat reflective of those in the veterans with SCI population. Veterans under the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical care have the option to seek care or procedures in non-VA facilities. If allergies to antibiotics occurred outside of the VA system, there is no mechanism to automatically merge with the VA EHR allergy list, unless they are later recorded and added to the VA EHR. Thus, there is potential for underreporting.

Drug anaphylaxis incidence was noted to change over time.4,8,9 For example, a downtrend of reported antibiotic allergy was reported between 1990 and 2013.10 Our study only reflects an overall prevalence of a single cohort, without demonstration of relationship to time.

Lastly, this study did not aim to differentiate HSRs from other ADRs. This is exactly the point of the study, which investigated the frequency of EHR-recorded antibiotic allergies in our SCI population and reflects the issue with indiscriminate recording of ADRs and HSRs under the umbrella of allergy in the EHR. Further diagnosing true allergies should be considered in the SCI population after weighing the risks and benefits of assessment, aligning with the wishes of the veteran, obtaining informed consent, and addressing the cost-effectiveness of specific tests. We suggest that primary care practitioners work closely with allergy specialists to formulate a mechanism to diagnose various antibiotic allergic reactions, including serum tryptase, epicutaneous skin testing, intradermal skin testing, patch testing, delayed intradermal testing, and drug challenge as appropriate. It is also possible that in cases where very mild reactions/adverse effects of antibiotics were recorded in the EHR, the clinicians and veterans may discuss reintroducing the same antibiotics or proceeding with further testing if necessary. In contrast, the 12% of those with a high risk of severe allergic reactions to penicillin in our study would benefit from allergist evaluation and access to epinephrine auto-injectors at all times. Differentiating true allergy is the only clear way to deter unnecessary avoidance of first-line therapies for antibiotic treatment and avoid promotion of antibiotic resistance.

Future studies can analyze antibiotic allergy based on demographics, including sex and age difference, as well as exploring outpatient vs inpatient settings. Aside from prevalence, we hope to demonstrate antibiotic allergy over time, especially after integration of diagnostic allergy testing, to evaluate the impact to EHR-recorded allergies.

Conclusions

Almost 30% of patients with SCI had a recorded allergy to at least 1 antibiotic. The most common allergy was to penicillin, which is similar to what has previously been reported for the general adult US population. However, only 12% of those with a penicillin allergy were considered high risk of true allergic reactions. Consequently, there are opportunities to examine whether approaches to confirm true reactions (such as skin testing) would help to mitigate unnecessary avoidance of certain antibiotic classes due to mild ADRs, rather than a true allergy, in persons with SCI. This would be an important effort to combat both individual safety concerns and the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance. Given the available evidence, it is reasonable for SCI health care practitioners to discuss the potential risks and benefits of allergy testing with patients with SCI; this maintains a patient-centered approach that can ensure judicious use of antibiotics when necessary.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported (or supported in part) with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital

References

1. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems. 2016 Annual Report –Complete Public Version. University of Alabama at Birmingham. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/2016%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf

2. Macy E, Richter PK, Falkoff R, Zeiger R. Skin testing with penicilloate and penilloate prepared by an improved method: amoxicillin oral challenge in patients with negative skin test responses to penicillin reagents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(5):586-591. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70159-3 3. Dhopeshwarkar N, Sheikh A, Doan R, et al. Drug-induced anaphylaxis documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.010

4. Evans CT, LaVela SL, Weaver FM, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(3):234-242. doi:10.1086/527509

5. Evans CT, Jump RL, Krein SL, et al. Setting a research agenda in prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) outside of acute care settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(2):210-213. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.291

6. Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phllips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183-198. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 7. Evans CT, Fitzpatrick MA, Jones MM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms in patients with spinal cord injury. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(12):1464-1471. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.238 8. Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

9. Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

10. Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praça F, Gomes L, Mariño E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(10):1597-1601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02070.x

References

1. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems. 2016 Annual Report –Complete Public Version. University of Alabama at Birmingham. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/2016%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf

2. Macy E, Richter PK, Falkoff R, Zeiger R. Skin testing with penicilloate and penilloate prepared by an improved method: amoxicillin oral challenge in patients with negative skin test responses to penicillin reagents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(5):586-591. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70159-3 3. Dhopeshwarkar N, Sheikh A, Doan R, et al. Drug-induced anaphylaxis documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.010

4. Evans CT, LaVela SL, Weaver FM, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(3):234-242. doi:10.1086/527509

5. Evans CT, Jump RL, Krein SL, et al. Setting a research agenda in prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) outside of acute care settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(2):210-213. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.291

6. Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phllips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183-198. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 7. Evans CT, Fitzpatrick MA, Jones MM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms in patients with spinal cord injury. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(12):1464-1471. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.238 8. Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

9. Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

10. Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praça F, Gomes L, Mariño E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(10):1597-1601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02070.x