User login

Prevalence of Antibiotic Allergy at a Spinal Cord Injury Center

Infectious diseases are the most common reason for rehospitalization among patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI), regardless of the number of years postinjury.1 The appropriate use and selection of antibiotics for properly diagnosed infectious diseases is especially important for this population. This principle helps to avoid the development of drug-resistant organisms and reduces the risk of recurrent infections, aligning with antibiotic stewardship.

Antibiotics are the most common class of drug allergies in the general population, and penicillin is the most frequently reported allergen (up to 10%).2 Prescription drug–induced anaphylaxis is severe and life threatening with a reported frequency of 1.1%. Penicillin and sulfonamide (46 and 15 per 10,000 patients, respectively) are the most common allergens.3 Although there is a significant difference between an adverse drug reaction (ADR) and true hypersensitivity, once documented in the electronic health record (EHR) as an allergy, this information deters use of the listed drugs.

Genitourinary, skin, and respiratory diseases are the leading causes for rehospitalization in patients with SCI.1 A large proportion of these are infectious in etiology and require antibiotic treatment. In fact, persons with SCI are at high risk for antibiotic overuse and hospital-acquired infection due to chronic bacteriuria, frequent health care exposure, implanted medical devices, and other factors.4 Concurrently, there is a crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria proliferation, described as a threat to patient safety and public health.5,6 Its severity is illustrated by the report that 38% of the cultures from patients with spinal cord injury are multidrug resistant gram-negative organisms.7

The SCI center at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, serves a high concentration of active-duty military members and veterans with SCI. A study that reviews the exact frequency of antibiotic drug allergies listed on the EHR would be a key first step to identify the magnitude of this issue. The results could guide investigation into differentiating true allergies from ADRs, thereby widening the options for potentially life-saving antibiotic treatment.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients included in the local SCI registry between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We collected data on patient demographics (age, sex, race and ethnicity) and a description of patients’ injuries (International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury [ISNCSCI] and etiology of injury [traumatic vs atraumatic]). The outcomes included antibiotic allergy and ADRs.

In the EHR, allergies can be listed toward an antibiotic class or a specific antibiotic. An allergy to each specific antibiotic would be recorded separately; however, overlap among antibiotic classes was not duplicated. For example, if a subject has a listed antibiotic allergy to ceftriaxone and cefepime with listed reactions, we would record allergies to each of these antibiotics but would only report a single allergy to the cephalosporin subclass.

Since we did not differentiate hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) from other ADRs, the reported reactions were grouped by signs and symptoms. There is a variety of terms used to report similar reactions, and best efforts were made to record the data as accurately as possible. Patient-reported history for risk stratification is a tool we used to group these historical reactions into high- vs low-risk for severe reactions. High-risk signs are those listed as anaphylaxis; anaphylactic reactions; angioedema presenting as swelling of mouth, eyes, lips, or tongue; blisters or ulcers involving the lips, mouth, eyes, urethra, vagina, or peeling skin; respiratory changes; shortness of breath; dyspnea; hypotension; or organ involvement (kidneys, lungs, liver).6

Inclusion criteria were all veterans who were diagnosed with tetraplegia or paraplegia and received annual evaluation between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We chose this period because it was the beginning of a financial year at the JAHVH SCI department using the SCI registry. The SCI annual evaluation is a routine practitioner encounter with the veteran, along with appropriate laboratory testing and imaging to follow up potential chronic health issues specific to patients with SCI. Annual evaluations provide an opportunity to maintain routine health screening and preventive care. Patients who had significant portions of data missing or missing elements of primary outcomes were excluded from analysis. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (VA IRBNet #1573370-4 on September 9, 2019).

Results

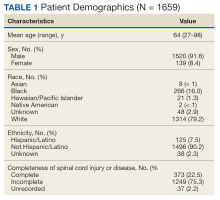

Of 1866 patients reviewed, 207 (11.1%) were excluded due to missing data, resulting in 1659 records that were analyzed. Mean age was 64 years, and male to female ratio was about 10 to 1. Most of the SCI or diseases were classified as incomplete (n = 1249) per ISNCSCI (absence of sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments) compared with 373 classified as complete.

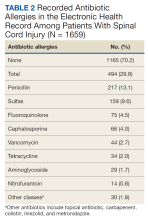

Of the 1659 patients, 494 (29.8%) had a recorded allergy to antibiotics. The most frequently recorded were 217 penicillin (13.1%), 159 sulfa drugs (9.6%), 75 fluoroquinolone (4.5%), 66 cephalosporin (4.0%), and 44 vancomycin (2.7%) allergies.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the frequency and characteristics of antibiotic allergies at a single SCI center to better identify potential areas for quality improvement when recording drug allergies. A study in the general population used self-reported methods to collect such information found about a 15% prevalence of antibiotic allergy, which was lower than the 29.8% prevalence noted in our study.8

Regarding the most common antibiotic allergies, one study reported allergy to penicillin in the EHR in 12.8% of patients at a major US regional health care system, while 13.1% of patients with SCI had documented allergy to penicillin in our study.9 Regarding the other antibiotic classes, the percentage of allergies were higher than those reported in the general population: sulfonamide (9.6% vs 7.4%), fluoroquinolones (4.5% vs 1.3%), and cephalosporins (4.0% vs 1.7%).10 The EHR appears to capture a much higher rate of antibiotic allergies than that in self-reported studies, such as a study of self-reported allergy in the general adult population in Portugal, where only 4.5% of patients reported allergy to any β-lactam medications.10

The prevalence of an antibiotic allergy could be affected by the health care setting and sex distribution. For example, the Zhou and colleagues’ study conducted in the Greater Boston area showed higher reported antibiotic rates than those in a study from a Southern California medical group. The higher proportion of tertiary referral patients in that specific network was suggested to be the cause of the difference.8,9 Our results in the SCI population are more comparable to that in a tertiary setting. This is consistent with the fact that persons with SCI generally have more exposure to antibiotics and consequently a higher reported rate of allergic reactions to antibiotics.

Similarly, the same study in Southern California noted that female patients use more antibiotics than do male patients, thus potentially contributing to higher rates of reported allergy toward all classes of antibiotics.8 Our study did not investigate antibiotic allergy by sex; however, the significantly higher proportion of male sex among the veteran population would have impacted these results.

Limitations

Our study was limited as a single-center retrospective study. However, our center is one of the major SCI specialty hubs, and the results should be somewhat reflective of those in the veterans with SCI population. Veterans under the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical care have the option to seek care or procedures in non-VA facilities. If allergies to antibiotics occurred outside of the VA system, there is no mechanism to automatically merge with the VA EHR allergy list, unless they are later recorded and added to the VA EHR. Thus, there is potential for underreporting.

Drug anaphylaxis incidence was noted to change over time.4,8,9 For example, a downtrend of reported antibiotic allergy was reported between 1990 and 2013.10 Our study only reflects an overall prevalence of a single cohort, without demonstration of relationship to time.

Lastly, this study did not aim to differentiate HSRs from other ADRs. This is exactly the point of the study, which investigated the frequency of EHR-recorded antibiotic allergies in our SCI population and reflects the issue with indiscriminate recording of ADRs and HSRs under the umbrella of allergy in the EHR. Further diagnosing true allergies should be considered in the SCI population after weighing the risks and benefits of assessment, aligning with the wishes of the veteran, obtaining informed consent, and addressing the cost-effectiveness of specific tests. We suggest that primary care practitioners work closely with allergy specialists to formulate a mechanism to diagnose various antibiotic allergic reactions, including serum tryptase, epicutaneous skin testing, intradermal skin testing, patch testing, delayed intradermal testing, and drug challenge as appropriate. It is also possible that in cases where very mild reactions/adverse effects of antibiotics were recorded in the EHR, the clinicians and veterans may discuss reintroducing the same antibiotics or proceeding with further testing if necessary. In contrast, the 12% of those with a high risk of severe allergic reactions to penicillin in our study would benefit from allergist evaluation and access to epinephrine auto-injectors at all times. Differentiating true allergy is the only clear way to deter unnecessary avoidance of first-line therapies for antibiotic treatment and avoid promotion of antibiotic resistance.

Future studies can analyze antibiotic allergy based on demographics, including sex and age difference, as well as exploring outpatient vs inpatient settings. Aside from prevalence, we hope to demonstrate antibiotic allergy over time, especially after integration of diagnostic allergy testing, to evaluate the impact to EHR-recorded allergies.

Conclusions

Almost 30% of patients with SCI had a recorded allergy to at least 1 antibiotic. The most common allergy was to penicillin, which is similar to what has previously been reported for the general adult US population. However, only 12% of those with a penicillin allergy were considered high risk of true allergic reactions. Consequently, there are opportunities to examine whether approaches to confirm true reactions (such as skin testing) would help to mitigate unnecessary avoidance of certain antibiotic classes due to mild ADRs, rather than a true allergy, in persons with SCI. This would be an important effort to combat both individual safety concerns and the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance. Given the available evidence, it is reasonable for SCI health care practitioners to discuss the potential risks and benefits of allergy testing with patients with SCI; this maintains a patient-centered approach that can ensure judicious use of antibiotics when necessary.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported (or supported in part) with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital

References

1. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems. 2016 Annual Report –Complete Public Version. University of Alabama at Birmingham. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/2016%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf

2. Macy E, Richter PK, Falkoff R, Zeiger R. Skin testing with penicilloate and penilloate prepared by an improved method: amoxicillin oral challenge in patients with negative skin test responses to penicillin reagents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(5):586-591. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70159-3 3. Dhopeshwarkar N, Sheikh A, Doan R, et al. Drug-induced anaphylaxis documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.010

4. Evans CT, LaVela SL, Weaver FM, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(3):234-242. doi:10.1086/527509

5. Evans CT, Jump RL, Krein SL, et al. Setting a research agenda in prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) outside of acute care settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(2):210-213. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.291

6. Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phllips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183-198. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 7. Evans CT, Fitzpatrick MA, Jones MM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms in patients with spinal cord injury. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(12):1464-1471. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.238 8. Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

9. Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

10. Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praça F, Gomes L, Mariño E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(10):1597-1601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02070.x

Infectious diseases are the most common reason for rehospitalization among patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI), regardless of the number of years postinjury.1 The appropriate use and selection of antibiotics for properly diagnosed infectious diseases is especially important for this population. This principle helps to avoid the development of drug-resistant organisms and reduces the risk of recurrent infections, aligning with antibiotic stewardship.

Antibiotics are the most common class of drug allergies in the general population, and penicillin is the most frequently reported allergen (up to 10%).2 Prescription drug–induced anaphylaxis is severe and life threatening with a reported frequency of 1.1%. Penicillin and sulfonamide (46 and 15 per 10,000 patients, respectively) are the most common allergens.3 Although there is a significant difference between an adverse drug reaction (ADR) and true hypersensitivity, once documented in the electronic health record (EHR) as an allergy, this information deters use of the listed drugs.

Genitourinary, skin, and respiratory diseases are the leading causes for rehospitalization in patients with SCI.1 A large proportion of these are infectious in etiology and require antibiotic treatment. In fact, persons with SCI are at high risk for antibiotic overuse and hospital-acquired infection due to chronic bacteriuria, frequent health care exposure, implanted medical devices, and other factors.4 Concurrently, there is a crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria proliferation, described as a threat to patient safety and public health.5,6 Its severity is illustrated by the report that 38% of the cultures from patients with spinal cord injury are multidrug resistant gram-negative organisms.7

The SCI center at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, serves a high concentration of active-duty military members and veterans with SCI. A study that reviews the exact frequency of antibiotic drug allergies listed on the EHR would be a key first step to identify the magnitude of this issue. The results could guide investigation into differentiating true allergies from ADRs, thereby widening the options for potentially life-saving antibiotic treatment.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients included in the local SCI registry between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We collected data on patient demographics (age, sex, race and ethnicity) and a description of patients’ injuries (International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury [ISNCSCI] and etiology of injury [traumatic vs atraumatic]). The outcomes included antibiotic allergy and ADRs.

In the EHR, allergies can be listed toward an antibiotic class or a specific antibiotic. An allergy to each specific antibiotic would be recorded separately; however, overlap among antibiotic classes was not duplicated. For example, if a subject has a listed antibiotic allergy to ceftriaxone and cefepime with listed reactions, we would record allergies to each of these antibiotics but would only report a single allergy to the cephalosporin subclass.

Since we did not differentiate hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) from other ADRs, the reported reactions were grouped by signs and symptoms. There is a variety of terms used to report similar reactions, and best efforts were made to record the data as accurately as possible. Patient-reported history for risk stratification is a tool we used to group these historical reactions into high- vs low-risk for severe reactions. High-risk signs are those listed as anaphylaxis; anaphylactic reactions; angioedema presenting as swelling of mouth, eyes, lips, or tongue; blisters or ulcers involving the lips, mouth, eyes, urethra, vagina, or peeling skin; respiratory changes; shortness of breath; dyspnea; hypotension; or organ involvement (kidneys, lungs, liver).6

Inclusion criteria were all veterans who were diagnosed with tetraplegia or paraplegia and received annual evaluation between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We chose this period because it was the beginning of a financial year at the JAHVH SCI department using the SCI registry. The SCI annual evaluation is a routine practitioner encounter with the veteran, along with appropriate laboratory testing and imaging to follow up potential chronic health issues specific to patients with SCI. Annual evaluations provide an opportunity to maintain routine health screening and preventive care. Patients who had significant portions of data missing or missing elements of primary outcomes were excluded from analysis. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (VA IRBNet #1573370-4 on September 9, 2019).

Results

Of 1866 patients reviewed, 207 (11.1%) were excluded due to missing data, resulting in 1659 records that were analyzed. Mean age was 64 years, and male to female ratio was about 10 to 1. Most of the SCI or diseases were classified as incomplete (n = 1249) per ISNCSCI (absence of sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments) compared with 373 classified as complete.

Of the 1659 patients, 494 (29.8%) had a recorded allergy to antibiotics. The most frequently recorded were 217 penicillin (13.1%), 159 sulfa drugs (9.6%), 75 fluoroquinolone (4.5%), 66 cephalosporin (4.0%), and 44 vancomycin (2.7%) allergies.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the frequency and characteristics of antibiotic allergies at a single SCI center to better identify potential areas for quality improvement when recording drug allergies. A study in the general population used self-reported methods to collect such information found about a 15% prevalence of antibiotic allergy, which was lower than the 29.8% prevalence noted in our study.8

Regarding the most common antibiotic allergies, one study reported allergy to penicillin in the EHR in 12.8% of patients at a major US regional health care system, while 13.1% of patients with SCI had documented allergy to penicillin in our study.9 Regarding the other antibiotic classes, the percentage of allergies were higher than those reported in the general population: sulfonamide (9.6% vs 7.4%), fluoroquinolones (4.5% vs 1.3%), and cephalosporins (4.0% vs 1.7%).10 The EHR appears to capture a much higher rate of antibiotic allergies than that in self-reported studies, such as a study of self-reported allergy in the general adult population in Portugal, where only 4.5% of patients reported allergy to any β-lactam medications.10

The prevalence of an antibiotic allergy could be affected by the health care setting and sex distribution. For example, the Zhou and colleagues’ study conducted in the Greater Boston area showed higher reported antibiotic rates than those in a study from a Southern California medical group. The higher proportion of tertiary referral patients in that specific network was suggested to be the cause of the difference.8,9 Our results in the SCI population are more comparable to that in a tertiary setting. This is consistent with the fact that persons with SCI generally have more exposure to antibiotics and consequently a higher reported rate of allergic reactions to antibiotics.

Similarly, the same study in Southern California noted that female patients use more antibiotics than do male patients, thus potentially contributing to higher rates of reported allergy toward all classes of antibiotics.8 Our study did not investigate antibiotic allergy by sex; however, the significantly higher proportion of male sex among the veteran population would have impacted these results.

Limitations

Our study was limited as a single-center retrospective study. However, our center is one of the major SCI specialty hubs, and the results should be somewhat reflective of those in the veterans with SCI population. Veterans under the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical care have the option to seek care or procedures in non-VA facilities. If allergies to antibiotics occurred outside of the VA system, there is no mechanism to automatically merge with the VA EHR allergy list, unless they are later recorded and added to the VA EHR. Thus, there is potential for underreporting.

Drug anaphylaxis incidence was noted to change over time.4,8,9 For example, a downtrend of reported antibiotic allergy was reported between 1990 and 2013.10 Our study only reflects an overall prevalence of a single cohort, without demonstration of relationship to time.

Lastly, this study did not aim to differentiate HSRs from other ADRs. This is exactly the point of the study, which investigated the frequency of EHR-recorded antibiotic allergies in our SCI population and reflects the issue with indiscriminate recording of ADRs and HSRs under the umbrella of allergy in the EHR. Further diagnosing true allergies should be considered in the SCI population after weighing the risks and benefits of assessment, aligning with the wishes of the veteran, obtaining informed consent, and addressing the cost-effectiveness of specific tests. We suggest that primary care practitioners work closely with allergy specialists to formulate a mechanism to diagnose various antibiotic allergic reactions, including serum tryptase, epicutaneous skin testing, intradermal skin testing, patch testing, delayed intradermal testing, and drug challenge as appropriate. It is also possible that in cases where very mild reactions/adverse effects of antibiotics were recorded in the EHR, the clinicians and veterans may discuss reintroducing the same antibiotics or proceeding with further testing if necessary. In contrast, the 12% of those with a high risk of severe allergic reactions to penicillin in our study would benefit from allergist evaluation and access to epinephrine auto-injectors at all times. Differentiating true allergy is the only clear way to deter unnecessary avoidance of first-line therapies for antibiotic treatment and avoid promotion of antibiotic resistance.

Future studies can analyze antibiotic allergy based on demographics, including sex and age difference, as well as exploring outpatient vs inpatient settings. Aside from prevalence, we hope to demonstrate antibiotic allergy over time, especially after integration of diagnostic allergy testing, to evaluate the impact to EHR-recorded allergies.

Conclusions

Almost 30% of patients with SCI had a recorded allergy to at least 1 antibiotic. The most common allergy was to penicillin, which is similar to what has previously been reported for the general adult US population. However, only 12% of those with a penicillin allergy were considered high risk of true allergic reactions. Consequently, there are opportunities to examine whether approaches to confirm true reactions (such as skin testing) would help to mitigate unnecessary avoidance of certain antibiotic classes due to mild ADRs, rather than a true allergy, in persons with SCI. This would be an important effort to combat both individual safety concerns and the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance. Given the available evidence, it is reasonable for SCI health care practitioners to discuss the potential risks and benefits of allergy testing with patients with SCI; this maintains a patient-centered approach that can ensure judicious use of antibiotics when necessary.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported (or supported in part) with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital

Infectious diseases are the most common reason for rehospitalization among patients with spinal cord injuries (SCI), regardless of the number of years postinjury.1 The appropriate use and selection of antibiotics for properly diagnosed infectious diseases is especially important for this population. This principle helps to avoid the development of drug-resistant organisms and reduces the risk of recurrent infections, aligning with antibiotic stewardship.

Antibiotics are the most common class of drug allergies in the general population, and penicillin is the most frequently reported allergen (up to 10%).2 Prescription drug–induced anaphylaxis is severe and life threatening with a reported frequency of 1.1%. Penicillin and sulfonamide (46 and 15 per 10,000 patients, respectively) are the most common allergens.3 Although there is a significant difference between an adverse drug reaction (ADR) and true hypersensitivity, once documented in the electronic health record (EHR) as an allergy, this information deters use of the listed drugs.

Genitourinary, skin, and respiratory diseases are the leading causes for rehospitalization in patients with SCI.1 A large proportion of these are infectious in etiology and require antibiotic treatment. In fact, persons with SCI are at high risk for antibiotic overuse and hospital-acquired infection due to chronic bacteriuria, frequent health care exposure, implanted medical devices, and other factors.4 Concurrently, there is a crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria proliferation, described as a threat to patient safety and public health.5,6 Its severity is illustrated by the report that 38% of the cultures from patients with spinal cord injury are multidrug resistant gram-negative organisms.7

The SCI center at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, serves a high concentration of active-duty military members and veterans with SCI. A study that reviews the exact frequency of antibiotic drug allergies listed on the EHR would be a key first step to identify the magnitude of this issue. The results could guide investigation into differentiating true allergies from ADRs, thereby widening the options for potentially life-saving antibiotic treatment.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients included in the local SCI registry between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We collected data on patient demographics (age, sex, race and ethnicity) and a description of patients’ injuries (International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury [ISNCSCI] and etiology of injury [traumatic vs atraumatic]). The outcomes included antibiotic allergy and ADRs.

In the EHR, allergies can be listed toward an antibiotic class or a specific antibiotic. An allergy to each specific antibiotic would be recorded separately; however, overlap among antibiotic classes was not duplicated. For example, if a subject has a listed antibiotic allergy to ceftriaxone and cefepime with listed reactions, we would record allergies to each of these antibiotics but would only report a single allergy to the cephalosporin subclass.

Since we did not differentiate hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) from other ADRs, the reported reactions were grouped by signs and symptoms. There is a variety of terms used to report similar reactions, and best efforts were made to record the data as accurately as possible. Patient-reported history for risk stratification is a tool we used to group these historical reactions into high- vs low-risk for severe reactions. High-risk signs are those listed as anaphylaxis; anaphylactic reactions; angioedema presenting as swelling of mouth, eyes, lips, or tongue; blisters or ulcers involving the lips, mouth, eyes, urethra, vagina, or peeling skin; respiratory changes; shortness of breath; dyspnea; hypotension; or organ involvement (kidneys, lungs, liver).6

Inclusion criteria were all veterans who were diagnosed with tetraplegia or paraplegia and received annual evaluation between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017. We chose this period because it was the beginning of a financial year at the JAHVH SCI department using the SCI registry. The SCI annual evaluation is a routine practitioner encounter with the veteran, along with appropriate laboratory testing and imaging to follow up potential chronic health issues specific to patients with SCI. Annual evaluations provide an opportunity to maintain routine health screening and preventive care. Patients who had significant portions of data missing or missing elements of primary outcomes were excluded from analysis. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board (VA IRBNet #1573370-4 on September 9, 2019).

Results

Of 1866 patients reviewed, 207 (11.1%) were excluded due to missing data, resulting in 1659 records that were analyzed. Mean age was 64 years, and male to female ratio was about 10 to 1. Most of the SCI or diseases were classified as incomplete (n = 1249) per ISNCSCI (absence of sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments) compared with 373 classified as complete.

Of the 1659 patients, 494 (29.8%) had a recorded allergy to antibiotics. The most frequently recorded were 217 penicillin (13.1%), 159 sulfa drugs (9.6%), 75 fluoroquinolone (4.5%), 66 cephalosporin (4.0%), and 44 vancomycin (2.7%) allergies.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the frequency and characteristics of antibiotic allergies at a single SCI center to better identify potential areas for quality improvement when recording drug allergies. A study in the general population used self-reported methods to collect such information found about a 15% prevalence of antibiotic allergy, which was lower than the 29.8% prevalence noted in our study.8

Regarding the most common antibiotic allergies, one study reported allergy to penicillin in the EHR in 12.8% of patients at a major US regional health care system, while 13.1% of patients with SCI had documented allergy to penicillin in our study.9 Regarding the other antibiotic classes, the percentage of allergies were higher than those reported in the general population: sulfonamide (9.6% vs 7.4%), fluoroquinolones (4.5% vs 1.3%), and cephalosporins (4.0% vs 1.7%).10 The EHR appears to capture a much higher rate of antibiotic allergies than that in self-reported studies, such as a study of self-reported allergy in the general adult population in Portugal, where only 4.5% of patients reported allergy to any β-lactam medications.10

The prevalence of an antibiotic allergy could be affected by the health care setting and sex distribution. For example, the Zhou and colleagues’ study conducted in the Greater Boston area showed higher reported antibiotic rates than those in a study from a Southern California medical group. The higher proportion of tertiary referral patients in that specific network was suggested to be the cause of the difference.8,9 Our results in the SCI population are more comparable to that in a tertiary setting. This is consistent with the fact that persons with SCI generally have more exposure to antibiotics and consequently a higher reported rate of allergic reactions to antibiotics.

Similarly, the same study in Southern California noted that female patients use more antibiotics than do male patients, thus potentially contributing to higher rates of reported allergy toward all classes of antibiotics.8 Our study did not investigate antibiotic allergy by sex; however, the significantly higher proportion of male sex among the veteran population would have impacted these results.

Limitations

Our study was limited as a single-center retrospective study. However, our center is one of the major SCI specialty hubs, and the results should be somewhat reflective of those in the veterans with SCI population. Veterans under the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical care have the option to seek care or procedures in non-VA facilities. If allergies to antibiotics occurred outside of the VA system, there is no mechanism to automatically merge with the VA EHR allergy list, unless they are later recorded and added to the VA EHR. Thus, there is potential for underreporting.

Drug anaphylaxis incidence was noted to change over time.4,8,9 For example, a downtrend of reported antibiotic allergy was reported between 1990 and 2013.10 Our study only reflects an overall prevalence of a single cohort, without demonstration of relationship to time.

Lastly, this study did not aim to differentiate HSRs from other ADRs. This is exactly the point of the study, which investigated the frequency of EHR-recorded antibiotic allergies in our SCI population and reflects the issue with indiscriminate recording of ADRs and HSRs under the umbrella of allergy in the EHR. Further diagnosing true allergies should be considered in the SCI population after weighing the risks and benefits of assessment, aligning with the wishes of the veteran, obtaining informed consent, and addressing the cost-effectiveness of specific tests. We suggest that primary care practitioners work closely with allergy specialists to formulate a mechanism to diagnose various antibiotic allergic reactions, including serum tryptase, epicutaneous skin testing, intradermal skin testing, patch testing, delayed intradermal testing, and drug challenge as appropriate. It is also possible that in cases where very mild reactions/adverse effects of antibiotics were recorded in the EHR, the clinicians and veterans may discuss reintroducing the same antibiotics or proceeding with further testing if necessary. In contrast, the 12% of those with a high risk of severe allergic reactions to penicillin in our study would benefit from allergist evaluation and access to epinephrine auto-injectors at all times. Differentiating true allergy is the only clear way to deter unnecessary avoidance of first-line therapies for antibiotic treatment and avoid promotion of antibiotic resistance.

Future studies can analyze antibiotic allergy based on demographics, including sex and age difference, as well as exploring outpatient vs inpatient settings. Aside from prevalence, we hope to demonstrate antibiotic allergy over time, especially after integration of diagnostic allergy testing, to evaluate the impact to EHR-recorded allergies.

Conclusions

Almost 30% of patients with SCI had a recorded allergy to at least 1 antibiotic. The most common allergy was to penicillin, which is similar to what has previously been reported for the general adult US population. However, only 12% of those with a penicillin allergy were considered high risk of true allergic reactions. Consequently, there are opportunities to examine whether approaches to confirm true reactions (such as skin testing) would help to mitigate unnecessary avoidance of certain antibiotic classes due to mild ADRs, rather than a true allergy, in persons with SCI. This would be an important effort to combat both individual safety concerns and the public health crisis of antibiotic resistance. Given the available evidence, it is reasonable for SCI health care practitioners to discuss the potential risks and benefits of allergy testing with patients with SCI; this maintains a patient-centered approach that can ensure judicious use of antibiotics when necessary.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported (or supported in part) with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital

References

1. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems. 2016 Annual Report –Complete Public Version. University of Alabama at Birmingham. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/2016%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf

2. Macy E, Richter PK, Falkoff R, Zeiger R. Skin testing with penicilloate and penilloate prepared by an improved method: amoxicillin oral challenge in patients with negative skin test responses to penicillin reagents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(5):586-591. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70159-3 3. Dhopeshwarkar N, Sheikh A, Doan R, et al. Drug-induced anaphylaxis documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.010

4. Evans CT, LaVela SL, Weaver FM, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(3):234-242. doi:10.1086/527509

5. Evans CT, Jump RL, Krein SL, et al. Setting a research agenda in prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) outside of acute care settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(2):210-213. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.291

6. Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phllips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183-198. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 7. Evans CT, Fitzpatrick MA, Jones MM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms in patients with spinal cord injury. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(12):1464-1471. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.238 8. Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

9. Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

10. Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praça F, Gomes L, Mariño E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(10):1597-1601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02070.x

References

1. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems. 2016 Annual Report –Complete Public Version. University of Alabama at Birmingham. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/2016%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf

2. Macy E, Richter PK, Falkoff R, Zeiger R. Skin testing with penicilloate and penilloate prepared by an improved method: amoxicillin oral challenge in patients with negative skin test responses to penicillin reagents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(5):586-591. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70159-3 3. Dhopeshwarkar N, Sheikh A, Doan R, et al. Drug-induced anaphylaxis documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.010

4. Evans CT, LaVela SL, Weaver FM, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in veterans with spinal cord injury and disorder. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(3):234-242. doi:10.1086/527509

5. Evans CT, Jump RL, Krein SL, et al. Setting a research agenda in prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) outside of acute care settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(2):210-213. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.291

6. Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phllips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):183-198. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 7. Evans CT, Fitzpatrick MA, Jones MM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms in patients with spinal cord injury. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(12):1464-1471. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.238 8. Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

9. Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

10. Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praça F, Gomes L, Mariño E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(10):1597-1601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02070.x

Prevalence and Predictors of Lower Limb Amputation in the Spinal Cord Injury Population

At the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, the prevalence of amputations among patients at the spinal cord injury (SCI) center seems high. Despite limited data demonstrating altered hemodynamics in the lower extremities (LEs) among the SCI population and increased frequency of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), amputations among patients with SCI have received little attention in research.1-3

In the United States, most amputations are caused by vascular disease related to peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and diabetes mellitus (DM).4 PAD primarily affects the LEs and is caused by atherosclerotic obstruction leading to insufficient blood flow. PAD can present clinically as LE pain, nonhealing ulcers, nonpalpable distal pulses, shiny or cold skin, absence of hair on the LE, or distal extremity pallor when the affected extremity is elevated. However, PAD is often asymptomatic. The diagnosis of PAD is typically made with an ankle-brachial index (ABI) ≤ 0.9.5 The prevalence of PAD is about 4.3% in Americans aged ≥ 40 years, increases with age, and is almost twice as common among Black Americans compared with that of White Americans.6 Many studies in SCI populations have documented an increased prevalence of DM, dyslipidemia, obesity, hypertension (HTN), and cigarette smoking.7-9 PAD shares these risk factors with coronary artery disease (CAD), but relative to CAD, tobacco smoking was a more substantial causative factor for PAD.10 Given the preponderance of associated risk factors in this population, PAD is likely more prevalent among patients with SCI than in the population without disabilities. Beyond these known risk factors, researchers hypothesized that SCI contributes to vascular disease by altering arterial function. However, this is still a topic of debate.11-13 Trauma also is a common cause of amputation, accounting for 45% of amputations in 2005.4 Patients with SCI may experience traumatic amputations simultaneously as their SCI, but they may also be predisposed to traumatic amputations related to osteopenia and impaired sensation.

Since amputation is an invasive surgery, knowing the severity of this issue is important in the SCI population. This study quantifies the prevalence of amputations of the LEs among the patients at our SCI center. It then characterizes these amputations’ etiology, their relationship with medical comorbidities, and certain SCI classifications.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Patient Record System. The cohort was defined as all patients who received an annual examination at our SCI center over 4 years from October 1, 2009 to September 30, 2013. Annual examination includes a physical examination, relevant surveillance laboratory tests, and imaging, such as renal ultrasound for those with indwelling urinary catheters. One characteristic of the patient population in the VA system is that diagnoses, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), that involve spinal cord lesions causing symptoms are included in the registry, besides those with other traumatic or nontraumatic SCI. October 1 to September 30 was chosen based on the VA fiscal year (FY).

During this period, 1678 patients had an annual examination. Of those, 299 patients had an SCI etiology of ALS or MS, and 41 had nonfocal SCI etiology that could not be assessed using the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) and were excluded. Also excluded were 283 patients who did not have an annual examination during the specified time span. Some patients do not have an annual examination every year; for those with multiple annual examinations during that time frame, the most recent was used.

One thousand fifty-five patients were included in the statistical analysis. Date of birth, sex, race, ethnicity, date of death, smoking status, DM diagnosis, HTN diagnosis, use of an antiplatelet, antihypertensive, or lipid-lowering agent, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, and lipid panel were collected. The amputation level and etiology were noted. The levels of amputation were classified as toe/partial foot,

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were summarized as the median and IQR for continuous variables or the number and percentage for categorical variables. The χ2 test was used to analyze the association between categorical variables and amputation status. A nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used to investigate the distribution of continuous variables across patients with amputation and patients without amputation. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to investigate amputation risk factors. We report goodness of fit using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test and the area under the curve (AUC) for the multivariate model. Statistical significance was prespecified at a 2-sided P < .05. SAS version 9.4 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

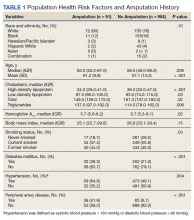

Mean age was approximately 61 years for the 91 patients at the time of the most recent amputation (Table 1). Among those with amputation, 63% were paraplegic and 37% were tetraplegic.

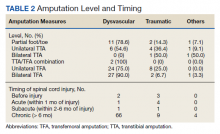

Of 1055 patients with SCI, 91 (8.6%) patients had an amputation. Of those, 70 (76.1%) were from nontraumatic causes (dysvascular), 17 (18.5%) were traumatic, 4 (4.3%) were from other causes (ie, cancer), and only 1 (1.1%) was of unknown cause.

Of the 91 patients with amputation, 64 (69.6%) had at least 1 TFA—33 were unilateral and 31 were bilateral. Two patients had a TFA on one side and a TTA on the other. Partial foot/toe and TTA were less common amputation levels with 14 (15.4%) and 13 (14.3%), respectively. Most amputations (86.8%) occurred over 6 months from the day of initial SCI, and were most commonly dysvascular (Table 2). Traumatic amputation occurred more evenly at various stages, pre-SCI, during acute SCI, subacute SCI, and chronic SCI.

Injury by Impairment Scale Level

Forty-nine (11.5%) of 426 patients with AIS level A SCI had undergone amputation. In order of prevalence, 23 (46.9%) were unilateral TFA, 17 (34.6%) were bilateral TFA, 10.2% were partial foot/toe, 4.1% were unilateral TTA, and 4.1% were a TTA/TFA combination. Both hip and knee disarticulations were classified in the TFA category.

Sixteen (13.0%) of 123 patients with AIS level B SCI had undergone amputation; 5 (31.3%) of those amputations were unilateral TFA, 6 (37.5%) were bilateral TFA, 3 (18.8%) were partial toe or foot, and 1 (6.3%) was for unilateral and bilateral TTA each.

Twelve (8.4%) of 143 patients with AIS level C SCI had undergone amputation: 6 (50.0%) were bilateral TFA; 3 (25.0%) were unilateral TFA; and 3 (25.0%) were unilateral TTA.

Fourteen (3.9%) of 356 patients with AIS level D SCI had undergone amputation. Of those 6 (42.9%) underwent a partial foot/toe amputation; 5 (35.7%) had undergone a unilateral TTA, and 1 (7.1%) underwent amputation in each of the following categories: bilateral TTA, unilateral TFA, and bilateral TFA each.

None of the 7 individuals with AIS E level SCI had undergone amputation.

Health Risk Factors

Of the 91 patients with amputation, the majority (81.3%) were either former or current smokers. Thirty-six percent of those who had undergone amputation had a diagnosis of DM, while only 21% of those who had not undergone amputation had a diagnosis of DM.

At the time of their annual examination 532 patients had a diagnosis of HTN while 523 patients did not. Among patients with amputations, 59 (64.8%) had HTN, while 32 (35.2%) did not. Of the 964 patients without amputation, the prevalence of HTN was 50.9%

.Of 1055 patients with SCI, only 103 (9.8%) had a PAD diagnosis, including 38 (41.9%) patients with amputation. Just 65 (6.7%) patients with SCI without amputation had PAD (P < .001). PAD is highly correlated with dysvascular causes of amputation. Among those with amputations due to dysvascular etiology, 50.0% (35/70) had PAD, but for the 21 amputations due to nondysvascular etiology, only 3 (14.3%) had PAD (P = .004).

Amputation Predictive Model

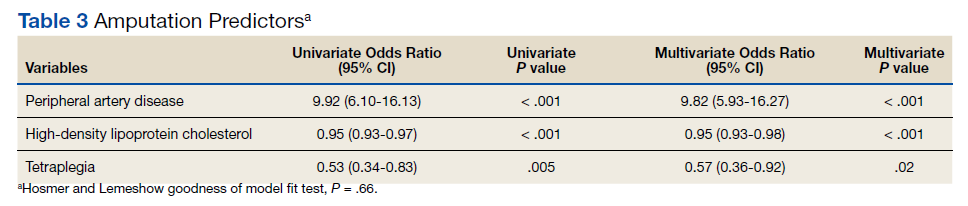

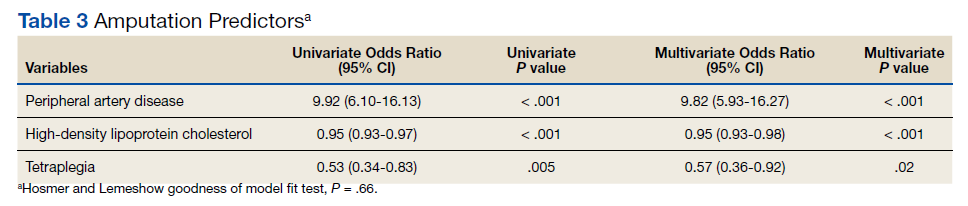

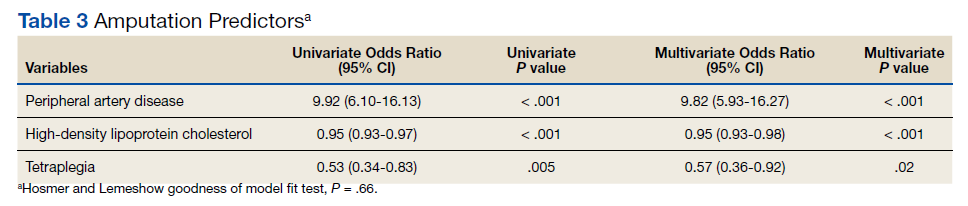

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to build a predictive model for amputation among patients with SCI while controlling for covariates. In our multivariate analysis, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), tetraplegia, and PAD were predictive factors for amputation. Patients with SCI who had PAD were 8.6 times more likely to undergo amputation compared to those without PAD (odds ratio [OR], 9.8; P < .001; 95% CI, 5.9-16.3). Every unit of HDL-C decreased the odds of amputation by 5% (OR, 0.95; P < .001; 95% CI, 0.93-0.98).

Having tetraplegia decreased the odds of amputation by 43%, compared with those with paraplegia (OR, 0.57; P = .02; 95% CI, 0.36 - 0.92). AUC was 0.76, and the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of model fit test P value was .66, indicating the good predictive power of the model (Table 3).

Discussion

In the US, 54 to 82% of amputations occur secondary to chronic vascular disease. Our study showed similar results: 76.1% of amputations were dysvascular.4,16 Even in a 2019 systematic review, the most recent prevalence of amputation data was in 2005.17 The study concluded that among the general population in the US, prevalence of amputation was estimated to be 1 in 190 people, or about 0.5% of the population.4 We found that the prevalence of amputation among the SCI population in this study was 8.7%. This result is consistent with our initial hypothesis that the prevalence of amputation would be higher among the people with SCI. Using a different case acquisition method, Svircev and colleagues reported that about a 4% prevalence of LE amputation among veterans with chronic SCI (over 1 year from the initial SCI), with an emphasis that it was not a study of amputation incidence.18 In comparison, we calculated a 7.5% prevalence of amputation during the chronic SCI stage, which showed institutional variation and a consistent observation that LE amputations occurred more frequently in the SCI population.

Our results showed a positive correlation between the completeness of injury and the prevalence of amputation. Those individuals with a motor complete injury, AIS A (40.3%) or AIS B (11.7%) account for approximately half of all amputations in our population with SCI. Another finding was that proximal amputations were more frequent with more neurologically complete SCIs. Of those with an injury classified as AIS A and an amputation, 42 of 49 subjects underwent at least 1 TFA (23 were unilateral TFA, 17 were bilateral TFA, 2 were a TFA/TTA combination). Of those with an AIS B injury and an amputation, 11 of 16 subjects (68.8%) had at least 1 TFA (5 unilateral TFA and 6 bilateral TFA). Among patients with AIS C injury and amputation, 75% had a TFA. At the same time, only 13.3% of all amputations were at the transfemoral level in those with an AIS D injury. None of the participants with an injury classified as AIS E had undergone an amputation.

Given a paucity of literature available regarding amputation levels in patients with SCI, a discussion with a JAHVH vascular surgeon helped explain the rationale behind different levels of amputation among the SCI population—TFA was performed in 64 of 91 cases (70%). Institutionally, TFAs were performed more often because this level had the greatest chance of healing, avoiding infection, and eliminating knee contracture issues, which may affect quality of life. This was believed to be the best option in those individuals who were already nonambulatory. Although this study did not collect data on ambulatory status, this helps explain why those with an SCI classification of AIS D were more likely to have had a more distal amputation to preserve current or a future chance of ambulation, provided that whether the limb is salvageable is the priority of surgical decision.

The prevalence of PAD among veterans is generally higher than it is in the nonveteran population. Studies show that the prevalence of PAD risk factors in the veteran population exceeds national estimates. Nearly two-thirds of veterans have HTN, 1 in 4 has DM, and 1 in 4 is a current smoker, placing veterans at a significantly increased risk of PADand, therefore, amputation.19,20 These rates were about the same or greater in our SCI population: 50.4% had HTN, 22.3% had a diagnosis of DM, and 71.8% smoked previously or currently smoked. In 3 large studies, HTN was second only to current smoking as the most attributable risk factor for PAD.21

Ongoing research by JAHVH vascular surgeons suggests that patients with SCI were younger and less likely to have HTN, PAD, and/or CAD compared with patients undergoing TFA without SCI. Additionally, patients with SCI had better postoperative outcomes in terms of 30-day mortality, 3-year mortality, and had no increased rate of surgical revisions, strokes, or wound-healing complications. This supports the previous thought that the AIS classification plays a large role in determining amputation levels.

One result in this study is that paraplegia is one of the predictors of future amputation compared with tetraplegia. To our knowledge, there is no literature that supports or explains this finding. A hypothetical factor that could explain this observation is the difference in duration of survival—those with paraplegia who live longer are more likely to experience end-stage consequence of vascular diseases. Another proposed factor is that those with paraplegia are generally more active and have a higher likelihood of sustaining a traumatic cause of amputation, even though this etiology of amputation is minor.An unexpected finding in our study was that of 1055 patients with SCI, only 9.8% had a PAD diagnosis. In contrast, 41.3% of those with amputation had a PAD diagnosis. JAHVH does not screen for PAD, so this likely represents only the symptomatic cases.

Diagnosing PAD in patients with SCI is challenging as they may lack classic clinical symptoms, such as pain with ambulation and impotence, secondary to their neurologic injury. Instead, the health care practitioner must rely on physical signs, such as necrosis.22 Of note given the undetermined utility of diagnosing PAD in patients with SCI, early endovascular interventions are not typically performed. We could not find literature regarding when intervention for PAD in patients with SCI should be performed or how frequently those with SCI should be assessed for PAD. One study showed impaired ambulation prior to limb salvage procedures was associated with poor functional outcomes in terms of survival, independent living, and ambulatory status.23 This could help explain why endovascular procedures are done relatively infrequently in this population. With the lack of studies regarding PAD in the SCI population, outcomes analysis of these patients, including the rate of initial interventions, re-intervention for re-amputation (possibly at a higher level), or vascular inflow procedures, are needed.

It would be beneficial for future studies to examine whether inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), were more elevated in patients with SCI who underwent amputation compared with those who did not. Chronic underlying inflammation has been shown to be a risk factor for PAD. One study showed that, independently of other risk factors, elevated CRP levels roughly tripled the risk of developing PAD.24 This study suggested that there is an increased risk of dysvascular amputation among the SCI population at this center. This information is significant because it can help influence JAHVH clinical practice for veterans with SCI and vascular diseases.

Limitations

As a single-center study carried out at an SCI specialized center of a VA hospital, this study's finding may not be generalizable. Incomplete documentation in the health record may have led to underreporting of amputations and other information. The practice of the vascular surgeons at JAHVH may not represent the approach of vascular surgeons nationwide. Another limitation of this study is that the duration of SCI was not considered when looking at health risk factors associated with amputation in the SCI population (ie, total cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c, etc). Finally, the medication regimens were not reviewed to determine whether they meet the standard of care in relation to eventual diagnosis of PAD.

A prospective study comparing the prevalence of amputation between veterans with SCI vs veterans without SCI could better investigate the difference in amputation risks. This study only compared our veterans with SCI in reference to the general population. Veterans are more likely to be smokers than the general population, contributing to PAD.17 In addition, data regarding patients’ functional status in regard to transferring and ambulation before and after amputation were not collected, which would have contributed to an understanding of how amputation affects functional status in this population.

Conclusions

There is an increased prevalence of amputation among veterans with SCI compared with that of the nationwide population and a plurality were TFAs. This data suggest that those with a motor complete SCI are more likely to undergo a more proximal amputation. This is likely secondary to a lower likelihood of ambulation with more neurologically complete injuries along with a greater chance of healing with a more proximal amputation. It is challenging to correlate any variables specific to SCI (ie, immobility, time since injury, level of injury, etc) with an increased risk of amputation as the known comorbidities associated with PAD are highly prevalent in this population. Having PAD, low HDL-C (< 40 mg/dL), and paraplegia instead of tetraplegia were independent predictors of amputation.

Health care professionals need to be aware of the high prevalence of amputation in the SCI population. Comorbidities should be aggressively treated as PAD, in addition to being associated with amputation, has been linked with increased mortality.25 Studies using a larger population and multiple centers are needed to confirm such a concerning finding.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported (or supported in part) with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH). Authors gratefully acknowledge the inputs and support of Dr. James Brooks, MD, RPVI, assistant professor of surgery, University of South Florida (USF), and attending surgeon, vascular surgery service, medical director of the peripheral vascular laboratory, JAHVH; and Dr. Kevin White, MD, assistant professor, USF, and Chief of Spinal Cord Injury Center, JAHVH.

1. Hopman MT, Nommensen E, van Asten WN, Oeseburg B, Binkhorst RA. Properties of the venous vascular system in the lower extremities of individuals with paraplegia. Paraplegia. 1994;32(12):810-816. doi:10.1038/sc.1994.128

2. Theisen D, Vanlandewijck Y, Sturbois X, Francaux M. Central and peripheral haemodynamics in individuals with paraplegia during light and heavy exercise. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33(1):16-20. doi:10.1080/165019701300006489

3. Bell JW, Chen D, Bahls M, Newcomer SC. Evidence for greater burden of peripheral arterial disease in lower extremity arteries of spinal cord-injured individuals. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(3):H766-H772. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00507.2011

4. Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(3):422-429. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005

5. Hennion DR, Siano KA. Diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(5):306-310.

6. Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Circulation. 2004;110(6):738-743. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000137913.26087.F0

7. Bauman WA, Spungen AM. Disorders of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in veterans with paraplegia or quadriplegia: a model of premature aging. Metabolism. 1994;43(6):749-756. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(94)90126-0

8. Jörgensen S, Hill M, Lexell J. Cardiovascular risk factors among older adults with long-term spinal cord injury. PM R. 2019;11(1):8-16. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.06.008

9. Wu JC, Chen YC, Liu L, et al. Increased risk of stroke after spinal cord injury: a nationwide 4-year follow-up cohort study. Neurology. 2012;78(14):1051-1057. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8eaa

10. Price JF, Mowbray PI, Lee AJ, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Fowkes FG. Relationship between smoking and cardiovascular risk factors in the development of peripheral arterial disease and coronary artery disease: Edinburgh Artery Study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(5):344-353. doi:10.1053/euhj.1998.1194

11. Bell JW, Chen D, Bahls M, Newcomer SC. Altered resting hemodynamics in lower-extremity arteries of individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2013;36(2):104-111. doi:10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000052

12. Miyatani M, Masani K, Oh PI, Miyachi M, Popovic MR, Craven BC. Pulse wave velocity for assessment of arterial stiffness among people with spinal cord injury: a pilot study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(1):72-78. doi:10.1080/10790268.2009.11760755

13. Oliver JJ, Webb DJ. Noninvasive assessment of arterial stiffness and risk of atherosclerotic events. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(4):554-566. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000060460.52916.D6

14. Ephraim PL, Dillifngham TR, Sector M, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Epidemiology of limb loss and congenital limb deficiency: a review of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(5): 747-761. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(02)04932-8.15. Levin ME. Preventing amputation in the patient with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(10)1383-1394. doi:10.2337/diacare.18.10.1383

16. Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the United States. South Med J. 2002;95(8):875-883. doi:10.1097/00007611- 200208000-00018

17. Lo J, Chan L, Flynn S. A systematic review of the incidence, prevalence, costs, and activity and work limitations of amputation, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, back pain, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, stroke, and traumatic brain injury in the United States: a 2019 update. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:115-131. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2020.04.001

18. Svircev, J, Tan D, Garrison A, Pennelly, B, Burns SP. Limb loss in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. doi:10.1080/10790268.2020.1800964

19. Brown DW. Smoking prevalence among US veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):147-149. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1160-0

20. Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al. The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1271-1276. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52355.x

21. Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res. 2015;116(9):1509-1526. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303849

22. Yokoo KM, Kronon M, Lewis VL Jr, McCarthy WJ, McMillan WD, Meyer PR Jr. Peripheral vascular disease in spinal cord injury patients: a difficult diagnosis. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37(5):495-499. doi:10.1097/00000637-199611000-00007

23. Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, Cass, et al. Determinants of functional outcome after revascularization for critical limb ischemia: an analysis of 1000 consecutive vascular interventions. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(4):747–756. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.015

24. Abdellaoui A, Al-Khaffaf H. C-reactive protein (CRP) as a marker in peripheral vascular disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34(1):18-22. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.10.040

25. Caro J, Migliaccio-Walle K, Ishak KJ, Proskorovsky I. The morbidity and mortality following a diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease: long-term follow-up of a large database. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5:14. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-14

At the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, the prevalence of amputations among patients at the spinal cord injury (SCI) center seems high. Despite limited data demonstrating altered hemodynamics in the lower extremities (LEs) among the SCI population and increased frequency of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), amputations among patients with SCI have received little attention in research.1-3

In the United States, most amputations are caused by vascular disease related to peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and diabetes mellitus (DM).4 PAD primarily affects the LEs and is caused by atherosclerotic obstruction leading to insufficient blood flow. PAD can present clinically as LE pain, nonhealing ulcers, nonpalpable distal pulses, shiny or cold skin, absence of hair on the LE, or distal extremity pallor when the affected extremity is elevated. However, PAD is often asymptomatic. The diagnosis of PAD is typically made with an ankle-brachial index (ABI) ≤ 0.9.5 The prevalence of PAD is about 4.3% in Americans aged ≥ 40 years, increases with age, and is almost twice as common among Black Americans compared with that of White Americans.6 Many studies in SCI populations have documented an increased prevalence of DM, dyslipidemia, obesity, hypertension (HTN), and cigarette smoking.7-9 PAD shares these risk factors with coronary artery disease (CAD), but relative to CAD, tobacco smoking was a more substantial causative factor for PAD.10 Given the preponderance of associated risk factors in this population, PAD is likely more prevalent among patients with SCI than in the population without disabilities. Beyond these known risk factors, researchers hypothesized that SCI contributes to vascular disease by altering arterial function. However, this is still a topic of debate.11-13 Trauma also is a common cause of amputation, accounting for 45% of amputations in 2005.4 Patients with SCI may experience traumatic amputations simultaneously as their SCI, but they may also be predisposed to traumatic amputations related to osteopenia and impaired sensation.

Since amputation is an invasive surgery, knowing the severity of this issue is important in the SCI population. This study quantifies the prevalence of amputations of the LEs among the patients at our SCI center. It then characterizes these amputations’ etiology, their relationship with medical comorbidities, and certain SCI classifications.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Patient Record System. The cohort was defined as all patients who received an annual examination at our SCI center over 4 years from October 1, 2009 to September 30, 2013. Annual examination includes a physical examination, relevant surveillance laboratory tests, and imaging, such as renal ultrasound for those with indwelling urinary catheters. One characteristic of the patient population in the VA system is that diagnoses, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), that involve spinal cord lesions causing symptoms are included in the registry, besides those with other traumatic or nontraumatic SCI. October 1 to September 30 was chosen based on the VA fiscal year (FY).

During this period, 1678 patients had an annual examination. Of those, 299 patients had an SCI etiology of ALS or MS, and 41 had nonfocal SCI etiology that could not be assessed using the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) and were excluded. Also excluded were 283 patients who did not have an annual examination during the specified time span. Some patients do not have an annual examination every year; for those with multiple annual examinations during that time frame, the most recent was used.

One thousand fifty-five patients were included in the statistical analysis. Date of birth, sex, race, ethnicity, date of death, smoking status, DM diagnosis, HTN diagnosis, use of an antiplatelet, antihypertensive, or lipid-lowering agent, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, and lipid panel were collected. The amputation level and etiology were noted. The levels of amputation were classified as toe/partial foot,

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were summarized as the median and IQR for continuous variables or the number and percentage for categorical variables. The χ2 test was used to analyze the association between categorical variables and amputation status. A nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used to investigate the distribution of continuous variables across patients with amputation and patients without amputation. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to investigate amputation risk factors. We report goodness of fit using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test and the area under the curve (AUC) for the multivariate model. Statistical significance was prespecified at a 2-sided P < .05. SAS version 9.4 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Mean age was approximately 61 years for the 91 patients at the time of the most recent amputation (Table 1). Among those with amputation, 63% were paraplegic and 37% were tetraplegic.

Of 1055 patients with SCI, 91 (8.6%) patients had an amputation. Of those, 70 (76.1%) were from nontraumatic causes (dysvascular), 17 (18.5%) were traumatic, 4 (4.3%) were from other causes (ie, cancer), and only 1 (1.1%) was of unknown cause.

Of the 91 patients with amputation, 64 (69.6%) had at least 1 TFA—33 were unilateral and 31 were bilateral. Two patients had a TFA on one side and a TTA on the other. Partial foot/toe and TTA were less common amputation levels with 14 (15.4%) and 13 (14.3%), respectively. Most amputations (86.8%) occurred over 6 months from the day of initial SCI, and were most commonly dysvascular (Table 2). Traumatic amputation occurred more evenly at various stages, pre-SCI, during acute SCI, subacute SCI, and chronic SCI.

Injury by Impairment Scale Level

Forty-nine (11.5%) of 426 patients with AIS level A SCI had undergone amputation. In order of prevalence, 23 (46.9%) were unilateral TFA, 17 (34.6%) were bilateral TFA, 10.2% were partial foot/toe, 4.1% were unilateral TTA, and 4.1% were a TTA/TFA combination. Both hip and knee disarticulations were classified in the TFA category.

Sixteen (13.0%) of 123 patients with AIS level B SCI had undergone amputation; 5 (31.3%) of those amputations were unilateral TFA, 6 (37.5%) were bilateral TFA, 3 (18.8%) were partial toe or foot, and 1 (6.3%) was for unilateral and bilateral TTA each.

Twelve (8.4%) of 143 patients with AIS level C SCI had undergone amputation: 6 (50.0%) were bilateral TFA; 3 (25.0%) were unilateral TFA; and 3 (25.0%) were unilateral TTA.

Fourteen (3.9%) of 356 patients with AIS level D SCI had undergone amputation. Of those 6 (42.9%) underwent a partial foot/toe amputation; 5 (35.7%) had undergone a unilateral TTA, and 1 (7.1%) underwent amputation in each of the following categories: bilateral TTA, unilateral TFA, and bilateral TFA each.

None of the 7 individuals with AIS E level SCI had undergone amputation.

Health Risk Factors

Of the 91 patients with amputation, the majority (81.3%) were either former or current smokers. Thirty-six percent of those who had undergone amputation had a diagnosis of DM, while only 21% of those who had not undergone amputation had a diagnosis of DM.

At the time of their annual examination 532 patients had a diagnosis of HTN while 523 patients did not. Among patients with amputations, 59 (64.8%) had HTN, while 32 (35.2%) did not. Of the 964 patients without amputation, the prevalence of HTN was 50.9%

.Of 1055 patients with SCI, only 103 (9.8%) had a PAD diagnosis, including 38 (41.9%) patients with amputation. Just 65 (6.7%) patients with SCI without amputation had PAD (P < .001). PAD is highly correlated with dysvascular causes of amputation. Among those with amputations due to dysvascular etiology, 50.0% (35/70) had PAD, but for the 21 amputations due to nondysvascular etiology, only 3 (14.3%) had PAD (P = .004).

Amputation Predictive Model

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to build a predictive model for amputation among patients with SCI while controlling for covariates. In our multivariate analysis, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), tetraplegia, and PAD were predictive factors for amputation. Patients with SCI who had PAD were 8.6 times more likely to undergo amputation compared to those without PAD (odds ratio [OR], 9.8; P < .001; 95% CI, 5.9-16.3). Every unit of HDL-C decreased the odds of amputation by 5% (OR, 0.95; P < .001; 95% CI, 0.93-0.98).

Having tetraplegia decreased the odds of amputation by 43%, compared with those with paraplegia (OR, 0.57; P = .02; 95% CI, 0.36 - 0.92). AUC was 0.76, and the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of model fit test P value was .66, indicating the good predictive power of the model (Table 3).

Discussion

In the US, 54 to 82% of amputations occur secondary to chronic vascular disease. Our study showed similar results: 76.1% of amputations were dysvascular.4,16 Even in a 2019 systematic review, the most recent prevalence of amputation data was in 2005.17 The study concluded that among the general population in the US, prevalence of amputation was estimated to be 1 in 190 people, or about 0.5% of the population.4 We found that the prevalence of amputation among the SCI population in this study was 8.7%. This result is consistent with our initial hypothesis that the prevalence of amputation would be higher among the people with SCI. Using a different case acquisition method, Svircev and colleagues reported that about a 4% prevalence of LE amputation among veterans with chronic SCI (over 1 year from the initial SCI), with an emphasis that it was not a study of amputation incidence.18 In comparison, we calculated a 7.5% prevalence of amputation during the chronic SCI stage, which showed institutional variation and a consistent observation that LE amputations occurred more frequently in the SCI population.

Our results showed a positive correlation between the completeness of injury and the prevalence of amputation. Those individuals with a motor complete injury, AIS A (40.3%) or AIS B (11.7%) account for approximately half of all amputations in our population with SCI. Another finding was that proximal amputations were more frequent with more neurologically complete SCIs. Of those with an injury classified as AIS A and an amputation, 42 of 49 subjects underwent at least 1 TFA (23 were unilateral TFA, 17 were bilateral TFA, 2 were a TFA/TTA combination). Of those with an AIS B injury and an amputation, 11 of 16 subjects (68.8%) had at least 1 TFA (5 unilateral TFA and 6 bilateral TFA). Among patients with AIS C injury and amputation, 75% had a TFA. At the same time, only 13.3% of all amputations were at the transfemoral level in those with an AIS D injury. None of the participants with an injury classified as AIS E had undergone an amputation.

Given a paucity of literature available regarding amputation levels in patients with SCI, a discussion with a JAHVH vascular surgeon helped explain the rationale behind different levels of amputation among the SCI population—TFA was performed in 64 of 91 cases (70%). Institutionally, TFAs were performed more often because this level had the greatest chance of healing, avoiding infection, and eliminating knee contracture issues, which may affect quality of life. This was believed to be the best option in those individuals who were already nonambulatory. Although this study did not collect data on ambulatory status, this helps explain why those with an SCI classification of AIS D were more likely to have had a more distal amputation to preserve current or a future chance of ambulation, provided that whether the limb is salvageable is the priority of surgical decision.

The prevalence of PAD among veterans is generally higher than it is in the nonveteran population. Studies show that the prevalence of PAD risk factors in the veteran population exceeds national estimates. Nearly two-thirds of veterans have HTN, 1 in 4 has DM, and 1 in 4 is a current smoker, placing veterans at a significantly increased risk of PADand, therefore, amputation.19,20 These rates were about the same or greater in our SCI population: 50.4% had HTN, 22.3% had a diagnosis of DM, and 71.8% smoked previously or currently smoked. In 3 large studies, HTN was second only to current smoking as the most attributable risk factor for PAD.21

Ongoing research by JAHVH vascular surgeons suggests that patients with SCI were younger and less likely to have HTN, PAD, and/or CAD compared with patients undergoing TFA without SCI. Additionally, patients with SCI had better postoperative outcomes in terms of 30-day mortality, 3-year mortality, and had no increased rate of surgical revisions, strokes, or wound-healing complications. This supports the previous thought that the AIS classification plays a large role in determining amputation levels.