User login

Care of the postpartum patient is an important component of primary care practice—particularly for clinicians who provide women’s health care and are called upon to effectively screen, identify, and manage patients who may be at risk for postpartum depression (PPD). Effective management of the postpartum patient also extends to care of her infant(s) and ideally should involve a multidisciplinary team, including the primary care provider, the pediatrician, and a psychologist or a psychiatrist.1

PPD is commonly described as depression that begins within the first month after delivery.2 It is diagnosed using the same criteria from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)3 as are used to identify major depressive disorder. According to the DSM-IV, PPD begins within the first four weeks after the infant’s birth.2,3 Although onset can occur at any time between 24 hours after a woman gives birth to several months later, PPD most commonly occurs within the first six weeks after delivery.1

The woman with PPD may be reluctant to report her symptoms for a number of reasons, including lack of motivation or energy, fatigue, embarrassment that she is experiencing such symptoms during a presumably happy time in her life—even fear that her child may be removed from her care.4 In addition to depressive symptoms (eg, sleeping difficulty, appetite changes, anhedonia, and guilt), women affected by PPD often experience anxiety and may become obsessed with the health, feeding, and sleeping behaviors of their infants.1,5

Postpartum mood disorders occur in a spectrum, ranging from postpartum baby blues to postpartum psychosis. By DSM-IV definition, a diagnosis of major or minor PPD requires that depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, or other characteristic symptoms be present most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks.3,6 PPD must be differentiated from the more common and less severe baby blues, which usually start two to three days after delivery and last less than two weeks.2,7 Between 40% and 80% of women who have given birth experience baby blues, which are characterized by transient mood swings, irritability, crying spells, difficulty sleeping, and difficulty concentrating.8 Experiencing baby blues may place women at increased risk for PPD.9

Postpartum, or puerperal, psychosis occurs in approximately 0.2% of women,10 with an early and sudden onset—that is, within the first week to four weeks postpartum. This severe condition is characterized by hallucinations and delusions often centered on the infant, in addition to insomnia, agitation, and extreme behavioral changes. Postpartum psychosis, which can recur in subsequent pregnancies, may be a manifestation of a preexisting affective disorder, such as bipolar disorder.10 Postpartum psychosis is considered an emergent condition because the safety and well-being of both mother and infant may be at serious risk.2,10

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

PPD is often cited as affecting 10% to 15% of women within the first year after childbirth.11,12 Currently, reported prevalence rates of PPD range from 5% to 20% of women who have recently given birth, depending on the source of information. Among 17 US states participating in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, a CDC surveillance project, prevalence of self-reported PPD symptoms ranged from 11.7% in Maine to 20.4% in New Mexico.11,13 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),14 the prevalence of major or minor depression ranges from 6.5% to 12.9% at different times during the year following delivery, although study design varied throughout the research used, and confidence intervals were deemed wide.14,15

Nevertheless, according to results from a systematic review of 28 studies, the prevalence of minor or major depression is estimated at up to 19.2% of women during the first three months postpartum, and major depression in up to 7% during that time.16 A 2007 chart review of 4,398 US women experiencing live births identified PPD in 10.4%.17

Incidence of PPD is “much higher than the quoted rate of 10% to 15%,” concludes Almond18 after a comprehensive literature review. The condition also affects women globally, the British researcher reports: Not only did she find numerous data on the incidence of PPD in high-income countries, including the US, the United Kingdom, and Australia, but she concluded that incidence rates of PPD in developing countries are grossly underestimated, according to epidemiologic studies in low- and middle-income countries (eg, Pakistan, Indonesia, Vietnam). Additionally, the risk factors for PPD are likely to be influenced by cultural differences, and attempts to identify PPD must be culturally sensitive.18

Several risk factors have been associated with PPD. Perhaps the most significant risk factor is a personal history of depression (prior to pregnancy or postpartum); at least one-half of women with PPD experience onset of depressive symptoms before or during their pregnancies,19,20 and one research group reported a relative risk (RR) of 1.87 for PPD in women with a history of depression, compared with those without such a history.21 Thus, women previously affected by depression should be carefully monitored in the immediate postpartum period for any signs of depressed mood, anxiety, sleep difficulties, loss of appetite or energy, and psychomotor changes.

According to McCoy et al,21 neither patient age nor marital status nor method of delivery appeared to be associated with PPD at four weeks postpartum. Women who were feeding by formula alone were more likely to experience PPD (RR, 2.04) than were those who breastfed their infants. Women who smoked were more likely to be affected by PPD (RR, 1.58) than were nonsmokers.

Additional risk factors for PPD identified by Dennis et al22 included pregnancy-induced hypertension and immigration within the previous five years. Various psychosocial stressors may also represent risk factors for PPD, including lack of social support, financial concerns, miscarriage or fetal demise, limited partner support, physical abuse before or during pregnancy, lack of readiness for hospital discharge, and complications during pregnancy and delivery (eg, low birth weight, premature birth, admission of the infant to the neonatal ICU).11,22,23

It is important to identify women who are at highest risk for PPD as soon as possible. High-risk patients should be screened upon discharge from the hospital and certainly on or before the first postpartum visit.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of PPD include depressed mood for at least two weeks with changes in somatic functions, such as sleep, energy level, appetite, weight, gastrointestinal functioning, and decrease in libido.3,24 These manifestations are more severe and prolonged than those associated with baby blues (which almost always resolve within two weeks postpartum).2,7

On physical examination, the patient with PPD may appear tearful and disheveled, with psychomotor retardation. She may report that she is unable to sleep even when her infant is sleeping, or that she has a significant lack of energy despite sufficient sleep; she may admit being unable to get out of bed for hours.2 The patient may report a significant decrease in appetite and little enjoyment in eating, which may lead to rapid weight loss.

Other symptoms may include obsessive thoughts about the infant and his or her care, significant anxiety (possibly manifested in panic attacks), uncontrollable crying, guilt, feelings of being overwhelmed or unable to care for the infant, mood swings, and severe irritability or even anger.2

Severe fatigue may warrant hemoglobin/hematocrit evaluation and possibly measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).25,26

It is essential to rule out postpartum psychosis, which is associated with prolonged lack of sleep, confusion, lapsed insight, cognitive impairment, “grossly disorganized behavior,”10 and delusions or hallucinations.5,10 The patient should be asked specifically about unusual or bizarre thoughts or beliefs concerning the infant, in addition to thoughts of harming herself or others, particularly the infant.10

SCREENING

Numerous researchers have suggested that PPD is underrecognized and undertreated.5,6,18,27,28 Screening for PPD in the United States is not standardized and is highly variable.29 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports universal screening for PPD at the first postpartum visit, between two and six weeks.30,31 According to a 2010 Committee Opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “at this time, there is insufficient evidence to support a firm recommendation for universal antepartum or postpartum screening; however, screening for depression has the potential to benefit a woman and her family and should be strongly considered.”32

As the AHRQ14 notes, symptoms of PPD may not peak in some women until after their first postpartum visit, and providers of family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatric care may also be in a position to provide screening. The initial well-baby examination by the pediatric primary care provider, for example, presents an important opportunity to screen new mothers for PPD. According to Chaudron et al,33 the well-being of the infant should outweigh any scope-of-practice concerns, practitioner time limitations, or reimbursement issues; rather, screening efforts can be considered “tools to enhance [mothers’] ability to care for their children in a way that is supportive and not punitive.”33

In 2009, Sheeder and colleagues28 reported on a prospective study of 199 mothers in an adolescent maternity clinic who were screened using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)34 at each well-baby visit during the first six months postpartum. The authors concluded that the optimal time for screening for PPD in this setting is two months after delivery, although repeated screening may identify worsening of depressive symptoms.28

Several screening tools are available for the detection of PPD, particularly the EPDS,34 the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale,35 and the Patient Health Questionnaire–936-38 (see table,11,13,34-37 ). The EPDS, a widely used and well-validated formal screening tool,27,37 is a 10-item self-report questionnaire designed to detect depression in the postpartum period. Cox et al,34 who developed the scale, initially reported its sensitivity at 86% and specificity at 78%21; since then, the tool’s reported sensitivity for detecting major depression in the postpartum period has ranged from 60% to 96%, and specificity from 45% to 97%.6,39 The EPDS has been shown to result in a diagnosis of PPD in significantly more women than routine clinical evaluation (35.4% vs 6.3%, respectively).40 It is possible to administer the EPDS by telephone.41

The validity of the EPDS tool in detecting PPD was recently examined in a systematic review of 37 studies. Gibson et al42 concluded that the heterogeneity of these studies (ie, differences in study methodology, language used, and diagnostic criteria) precluded meta-analysis and did not provide clear support of EPDS as an accurate screening tool for PPD, especially across diverse cultures. In a similar review, Hewitt and colleagues6 sought to “provide an overview of all available methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care and to assess their validity.” They concluded that the EPDS is the most frequently reported screening tool and, with an overall sensitivity of 86% and overall specificity of 87%, its diagnostic performance seems “reasonably good.”6 Of note, fewer data have been collected to demonstrate the effectiveness of other screening tools.35,36,38,41

Cost-effectiveness is a consideration in the use of screening programs for PPD. According to a hypothetical cohort analysis conducted in the UK, the costs of treating women with false-positive screening results made implementation of a formal screening strategy for PPD not cost-effective, compared with usual care only, for use by the British National Health Service.43

MANAGEMENT

Once PPD is identified, treatment should be initiated as quickly as possible; referral for psychological counseling is an appropriate initial strategy for mild to moderate symptoms of PPD.5 A clinical care manager can be a valuable resource to provide education and coordination of care for women affected by PPD. NPs and PAs in primary care, obstetrics/gynecology, women’s health, and psychiatry or psychology can play an important role in the identification and management of PPD.

Treatment of PPD involves combination therapy—short-term psychological therapy combined with pharmacotherapy. According to investigators in a Cochrane Review of nine trials reporting short-term outcomes for 956 women with PPD, their findings suggest that psychosocial and psychological interventions are an effective option for reducing symptoms of PPD.44 Compared with usual care, the types of psychological therapy that were found most effective included cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and psychodynamic therapy. As most trials’ follow-up periods were limited to six months, however, neither the long-term effects of psychological therapy nor the relative effectiveness of each type of therapy was made clear by these studies.44,45

Pharmacotherapy

Although antidepressant drugs are known to be effective for the treatment of major depressive disorder, well-designed clinical trials demonstrating the overall effectiveness of antidepressants in treatment of PPD have been limited.46 According to Ng et al,46 who in 2010 performed a systematic review of studies examining pharmacologic interventions for PPD, preliminary evidence showing the effectiveness of antidepressants and hormone therapy should prompt the initiation of larger, more rigorous randomized and controlled trials.

The choice of antidepressants will be influenced by the mother’s breastfeeding status and whether PPD represents her first episode of depression or a recurrence of previous major depression. If the patient is not breastfeeding, the choice among antidepressants is similar to those used for treatment of nonpuerperal major depression. If PPD is a relapse of a prior depression, the therapeutic agent that was most effective and best-tolerated for previous depression should be prescribed.47

Generally, the SSRIs are considered first-line agents because of their superior safety profile.47 Fluoxetine has been shown in a small randomized trial (n = 87) to be significantly more effective than placebo and as effective as a full course of cognitive-behavioral counseling.45 In non–placebo-controlled studies, sertraline, fluvoxamine, and venlafaxine all produced improvement in PPD symptoms.48,49

Whether the mother is breastfeeding her infant will influence the use and choice of antidepressants for PPD. Although barely detectable levels of certain antidepressant medications (including the SSRIs sertraline and paroxetine, and the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline) have been reported in breast milk or in infant serum,50,51 it is recommended that the lowest possible therapeutic dose be prescribed, and that infants be carefully monitored for adverse effects.51

Fluoxetine, it should be noted, has been found to be transmitted through breast milk and was associated with reduced infant weight gain (specifically, by 392 g over six months) in a comparison between 64 fluoxetine-treated mothers and 38 non-treated mother-infant pairs.52 Thus, fluoxetine use should be avoided in women who are breastfeeding.

In small studies, paroxetine and fluvoxamine were not detected in infant serum, and although low levels of sertraline were detected in one-fourth of infants whose mothers received doses exceeding 100 mg/d, no adverse infant outcomes were noted.52-54 Paroxetine, nortriptyline, and sertraline appear to be relatively safer antidepressant choices in breastfeeding women with PPD.50,52,53

Antidepressants should be continued for six months after full remission of depressive symptoms. Longer courses of therapy may be necessary in patients who experience recurrent major depressive episodes.55

Few researchers have reported on the use of hormonal therapy for PPD. Yet significant hormonal fluctuations,56,57 including “estrogen withdrawal at parturition,”56 are known to occur after childbirth; in their study of women with severe PPD, Ahokas et al57 found that two-thirds of participants had serum estradiol concentrations below the cutoff for gonadal failure. Such a deficiency is likely to contribute to mood disturbances.56,57

In a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that enrolled women with severe, persistent PPD (mean EPDS score, 21.8), six months’ treatment with transdermally administered estradiol was associated with significantly greater relief of depressive symptoms than was found in controls (mean EPDS scores at one month, 13.3 vs 16.5, respectively). Of note, more than half of the women studied were concurrently receiving antidepressants.58

Additional studies may elucidate the role of estrogen therapy in the treatment of PPD.

Nonpharmacologic Options

An effective nonpharmacologic option for rapid resolution of severe symptoms of PPD is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).59-61 Its use is safe in nursing mothers because it does not affect breast milk. ECT is considered especially useful for women who have not responded to pharmacotherapy, those experiencing severe psychotic depression, and those who are considered at high risk for suicide or infanticide.

Patients typically receive three treatments per week; three to six treatments often produce an effective response.59 Anesthesia administered to women who undergo ECT has not been shown to have a negative effect on infants who are being breastfed.60,61

Interpersonal strategies to address PPD should not be overlooked. A pilot study conducted in Canada showed promising results when women who had previously experienced PPD were trained to provide peer support by telephone to mothers who were deemed at high risk for PPD (ie, those with EPDS scores > 12). At four weeks and eight weeks postpartum, follow-up EPDS scores exceeded 12 in 10% and 15%, respectively, of women receiving peer support, compared with 41% and 52%, respectively, of controls.62

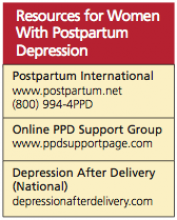

Participation in one of numerous support groups that exist for women with PPD (see box, for online information) may reduce isolation in these women and possibly offer additional benefits.

COMPLICATIONS

PPD may be associated with significant complications, underscoring the importance of prompt identification and treatment.5 Maternal depressive symptoms in the critical postnatal period, for example, have been associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bonding. In one study of 101 women, lower-quality maternal bonding was found in women who had symptoms of depression at two weeks, six weeks, and four months postpartum—but not in those with depression at 14 months.63 Additionally, it was found in a systematic review of 49 studies that women with PPD were likely to discontinue breastfeeding earlier than women not affected.64

Delayed growth and development has been reported in infants of mothers with untreated or inadequately treated PPD.65 It has also been suggested that children of depressed mothers may have an increased risk for anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and other behavioral disorders later in childhood.65-67

PROGNOSIS

Untreated PPD may resolve spontaneously within three to six months, but in about one-quarter of PPD patients, depressive symptoms persist one year after delivery.24,68,69 PPD increases a woman’s risk for future episodes of major depression.2,5

PREVENTION

As previously discussed, the risk for PPD is greatest in women with a history of mood disorders (25%) and PPD (50%).2 Although several approaches have been studied to prevent PPD, no clear optimal strategy has been revealed. In one Cochrane review, insufficient evidence was found to justify prophylactic use of antidepressants.70 Similarly, findings in a second review fell short of confirming the effectiveness of prenatal psychosocial or psychological interventions to prevent antenatal depression.71

Additional studies are needed to make recommendations on prevention of PPD in high-risk patients. Until such recommendations emerge, close monitoring, screening, and follow-up are essential for these women.

CONCLUSION

Postpartum depression is an important concern among childbearing women, as it is associated with adverse maternal and infant outcomes. A personal history of depression is a major risk factor for PPD. It is imperative to question women about signs and symptoms of depression during the immediate postpartum period; it is particularly important to inquire about thoughts of harm to self or to the infant.

Pharmacotherapy combined with adjunctive psychological therapy is indicated for new mothers with significant depressive symptoms. The choice of antidepressants is based on previous response to antidepressants and the woman’s breastfeeding status. Generally, SSRIs are effective and well tolerated for major depression; based on results from small studies, they appear to be safe for breastfeeding mothers.

Electroconvulsive therapy is considered a safe and effective option for women with severe symptoms of PPD.

REFERENCES

1. Muzik M, Marcus SM, Heringhausen JE, Flynn H. When depression complicates childbearing: guidelines for screening and treatment during antenatal and postpartum obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36(4):771-788.

2. Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM. Clinical practice: postpartum depression. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):194-199.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

4. Whitton A, Warner R, Appleby L. The pathway to care in post-natal depression: women’s attitudes to post-natal depression and its treatment. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(408):427-428.

5. Sit DK, Wisner KL. Identification of postpartum depression. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 52(3):456-468.

6. Hewitt C, Gilbody S, Brealey S, et al. Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: an integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(36):1-145, 147-230.

7. Epperson CN. Postpartum major depression: detection and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(8):2247-2254, 2259-2260.

8. O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Wright EJ. Prospective study of postpartum blues: biologic and psychosocial factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):801-806.

9. Hannah P, Adams D, Lee A, et al. Links between early post-partum mood and post-natal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:777-780.

10. Sit D, Rothschild AJ, Wisner KL. A review of postpartum psychosis. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(4):352-368.

11. CDC. Prevalence of self-reported postpartum depressive symptoms—17 states, 2004–2005. MMWR Weekly. 2008;57(14):361-366.

12. O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:37-54.

13. Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439-445.

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Perinatal Depression: Prevalence, Screening Accuracy, and Screening Outcomes: Summary. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 119. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/peridep sum.htm. Accessed January 24, 2011.

15. Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2005 Feb;(119):1-8.

16. Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 106(5 pt 1):1071-1083.

17. Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, et al. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10): 1515-1520.

18. Almond P. Postnatal depression a global public health perspective. Perspect Public Health. 2009;129(5):221-227.

19. Lee D, Yip A, Chiu H, et al. A psychiatric epidemiological study of postpartum Chinese women. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):220-226.

20. Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, et al. Post-partum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:554-558.

21. McCoy SJB, Beal JM, Miller SBM, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depression: a retrospective investigation at 4-weeks postnatal and a review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(4):193-198.

22. Dennis CL, Janssen PA, Singer J. Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(5):338-346.

23. Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1-2):147-157.

24. Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Postpartum mood disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 suppl 2:34-40.

25. Corwin EJ, Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Low hemoglobin level is a risk factor for postpartum depression. J Nutr. 2003;133(12):4139-4142.

26. McCoy SJ, Beal JM, Payton ME, et al. Postpartum thyroid measures and depressive symptomology: a pilot study. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008;108(9):503-507.

27. Seehusen DA, Baldwin LM, Runkle GP, Clark G. Are family physicians appropriately screening for postpartum depression? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(2):104-112.

28. Sheeder J, Kabir K, Stafford B. Screening for postpartum depression at well-child visits: is once enough during the first 6 months of life? Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):e982-e988.

29. Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, Zlotnick C. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(4):357-364.

30. Shaver K. Treating postpartum depression during lactation. Prescriber’s Letter. 2001 Aug;8(8):47.

31. Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Wollan P, Yawn BP. Routine screening for postpartum depression. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(20):117-122.

32. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 453: Screening for depression during and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):394-395.

33. Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Campbell AT, et al. Legal and ethical considerations: risks and benefits of postpartum depression screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):123-128.

34. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782-786.

35. Beck CT, Gable RK. Postpartum Depression Screening Scale: development and psychometric testing. Nurs Res. 2000;49(5):272-282.

36. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders, Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999; 282(18):1737-44.

37. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

38. Yawn BP, Pace W, Wollan PC, et al. Concordance of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to assess increased risk of depression among postpartum women. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(5):483-491.

39. Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157: 288-290.

40. Evins GG, Theofrastous JP, Galvin SL. Postpartum depression: a comparison of screening and routine clinical evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(5):1080-1082.

41. Hanusa BH, Scholle SH, Haskett RF, et al. Screening for depression in the postpartum period: a comparison of three instruments. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(4):585-596.

42. Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, et al. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(5):350-364.

43. Paulden M, Palmer S, Hewitt C, Gilbody S. Screening for postnatal depression in primary care: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2009; 339:b5203.

44. Dennis CL,Hodnett ED. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006116.

45. Appleby L, Warner R, Whitton A, Faragher B. A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioural counselling in the treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ. 1997;314(7085): 932-936.

46. Ng RC, Hirata CK, Yeung W, et al. Pharmacologic treatment for postpartum depression: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2010; 30(9):928-941.

47. Whitby DH, Smith KM. The use of tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in women who are breastfeeding. Phamacotherapy. 2005;25(3):411-425.

48. Suri R, Burt VK, Altshuler LL, et al. Fluvoxamine for postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1739-1740.

49. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, Bouffard SM, et al. Venlafaxine in the treatment of postpartum depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(8):592-596.

50. Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Perel JM, et al. Postpartum depression: a randomized trial of sertraline versus nortriptyline. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(4):353-360.

51. Freeman MP. Postpartum depression treatment and breastfeeding. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;79(9):e35.

52. Gjerdingen D. The effectiveness of various postpartum depression treatments and the impact of antidepressant drugs on nursing infants. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(5): 372-382.

53. Wisner KL, Perel JM, Findling RL. Antidepressant treatment during breast-feeding. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(9):1132-1137.

54. Hendrick V, Fukuchi A, Altshuler L, et al. Use of sertraline, paroxetine and fluvoxamine by nursing women. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179: 163-166.

55. Davidson JR. Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in America and Europe.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71 suppl E1:e04.

56. Moses-Kolko EL, Berga SL, Kalro B, et al. Transdermal estradiol for postpartum depression: a promising treatment option. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52(3):516-529.

57. Ahokas A, Kaukoranta J, Wahlbeck K, Aito M. Estrogen deficiency in severe postpartum depression: successful treatment with sublingual physiologic 17beta-estradiol: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(5):

332-336.

58. Gregoire AJ, Kumar R, Everitt B, et al. Transdermal oestrogen for treatment of severe postnatal depression. Lancet. 1996;347(9006): 930-933.

59. Forray A, Ostroff RB. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in postpartum affective disorders. J ECT. 2007;23(3):188-193.

60. Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, et al. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(5):592-606.

61. Rabheru K. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in special patient populations. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(8):710-719.

62. Dennis CL. The effect of peer support on postpartum depression: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(2): 115-124.

63. Moehler E, Brunner R, Wiebel A, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bonding. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):273-278.

64. Dennis CL, McQueen K. The relationship between infant-feeding outcomes and postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e736-e751.

65. Hirst KP, Moutier CY. Postpartum major depression. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(8): 926-933.

66. Beck CT. The effects of postpartum depression on child development: a meta-analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1998;12(1):12-20.

67. Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1389-1398.

68. Cooper PJ, Murray L. Course and recurrence of postnatal depression: evidence for the specificity of the diagnostic concept. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(2):191-195.

69. Kumar R, Robson KM. A prospective study of emotional disorders in childbearing women. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:35-47.

70. Howard LM, Hoffbrand S, Henshaw C, et al. Antidepressant prevention of postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD00436.

71. Dennis CL, Ross LE, Grigoriadis S. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating antenatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD006309.

Care of the postpartum patient is an important component of primary care practice—particularly for clinicians who provide women’s health care and are called upon to effectively screen, identify, and manage patients who may be at risk for postpartum depression (PPD). Effective management of the postpartum patient also extends to care of her infant(s) and ideally should involve a multidisciplinary team, including the primary care provider, the pediatrician, and a psychologist or a psychiatrist.1

PPD is commonly described as depression that begins within the first month after delivery.2 It is diagnosed using the same criteria from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)3 as are used to identify major depressive disorder. According to the DSM-IV, PPD begins within the first four weeks after the infant’s birth.2,3 Although onset can occur at any time between 24 hours after a woman gives birth to several months later, PPD most commonly occurs within the first six weeks after delivery.1

The woman with PPD may be reluctant to report her symptoms for a number of reasons, including lack of motivation or energy, fatigue, embarrassment that she is experiencing such symptoms during a presumably happy time in her life—even fear that her child may be removed from her care.4 In addition to depressive symptoms (eg, sleeping difficulty, appetite changes, anhedonia, and guilt), women affected by PPD often experience anxiety and may become obsessed with the health, feeding, and sleeping behaviors of their infants.1,5

Postpartum mood disorders occur in a spectrum, ranging from postpartum baby blues to postpartum psychosis. By DSM-IV definition, a diagnosis of major or minor PPD requires that depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, or other characteristic symptoms be present most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks.3,6 PPD must be differentiated from the more common and less severe baby blues, which usually start two to three days after delivery and last less than two weeks.2,7 Between 40% and 80% of women who have given birth experience baby blues, which are characterized by transient mood swings, irritability, crying spells, difficulty sleeping, and difficulty concentrating.8 Experiencing baby blues may place women at increased risk for PPD.9

Postpartum, or puerperal, psychosis occurs in approximately 0.2% of women,10 with an early and sudden onset—that is, within the first week to four weeks postpartum. This severe condition is characterized by hallucinations and delusions often centered on the infant, in addition to insomnia, agitation, and extreme behavioral changes. Postpartum psychosis, which can recur in subsequent pregnancies, may be a manifestation of a preexisting affective disorder, such as bipolar disorder.10 Postpartum psychosis is considered an emergent condition because the safety and well-being of both mother and infant may be at serious risk.2,10

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

PPD is often cited as affecting 10% to 15% of women within the first year after childbirth.11,12 Currently, reported prevalence rates of PPD range from 5% to 20% of women who have recently given birth, depending on the source of information. Among 17 US states participating in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, a CDC surveillance project, prevalence of self-reported PPD symptoms ranged from 11.7% in Maine to 20.4% in New Mexico.11,13 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),14 the prevalence of major or minor depression ranges from 6.5% to 12.9% at different times during the year following delivery, although study design varied throughout the research used, and confidence intervals were deemed wide.14,15

Nevertheless, according to results from a systematic review of 28 studies, the prevalence of minor or major depression is estimated at up to 19.2% of women during the first three months postpartum, and major depression in up to 7% during that time.16 A 2007 chart review of 4,398 US women experiencing live births identified PPD in 10.4%.17

Incidence of PPD is “much higher than the quoted rate of 10% to 15%,” concludes Almond18 after a comprehensive literature review. The condition also affects women globally, the British researcher reports: Not only did she find numerous data on the incidence of PPD in high-income countries, including the US, the United Kingdom, and Australia, but she concluded that incidence rates of PPD in developing countries are grossly underestimated, according to epidemiologic studies in low- and middle-income countries (eg, Pakistan, Indonesia, Vietnam). Additionally, the risk factors for PPD are likely to be influenced by cultural differences, and attempts to identify PPD must be culturally sensitive.18

Several risk factors have been associated with PPD. Perhaps the most significant risk factor is a personal history of depression (prior to pregnancy or postpartum); at least one-half of women with PPD experience onset of depressive symptoms before or during their pregnancies,19,20 and one research group reported a relative risk (RR) of 1.87 for PPD in women with a history of depression, compared with those without such a history.21 Thus, women previously affected by depression should be carefully monitored in the immediate postpartum period for any signs of depressed mood, anxiety, sleep difficulties, loss of appetite or energy, and psychomotor changes.

According to McCoy et al,21 neither patient age nor marital status nor method of delivery appeared to be associated with PPD at four weeks postpartum. Women who were feeding by formula alone were more likely to experience PPD (RR, 2.04) than were those who breastfed their infants. Women who smoked were more likely to be affected by PPD (RR, 1.58) than were nonsmokers.

Additional risk factors for PPD identified by Dennis et al22 included pregnancy-induced hypertension and immigration within the previous five years. Various psychosocial stressors may also represent risk factors for PPD, including lack of social support, financial concerns, miscarriage or fetal demise, limited partner support, physical abuse before or during pregnancy, lack of readiness for hospital discharge, and complications during pregnancy and delivery (eg, low birth weight, premature birth, admission of the infant to the neonatal ICU).11,22,23

It is important to identify women who are at highest risk for PPD as soon as possible. High-risk patients should be screened upon discharge from the hospital and certainly on or before the first postpartum visit.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of PPD include depressed mood for at least two weeks with changes in somatic functions, such as sleep, energy level, appetite, weight, gastrointestinal functioning, and decrease in libido.3,24 These manifestations are more severe and prolonged than those associated with baby blues (which almost always resolve within two weeks postpartum).2,7

On physical examination, the patient with PPD may appear tearful and disheveled, with psychomotor retardation. She may report that she is unable to sleep even when her infant is sleeping, or that she has a significant lack of energy despite sufficient sleep; she may admit being unable to get out of bed for hours.2 The patient may report a significant decrease in appetite and little enjoyment in eating, which may lead to rapid weight loss.

Other symptoms may include obsessive thoughts about the infant and his or her care, significant anxiety (possibly manifested in panic attacks), uncontrollable crying, guilt, feelings of being overwhelmed or unable to care for the infant, mood swings, and severe irritability or even anger.2

Severe fatigue may warrant hemoglobin/hematocrit evaluation and possibly measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).25,26

It is essential to rule out postpartum psychosis, which is associated with prolonged lack of sleep, confusion, lapsed insight, cognitive impairment, “grossly disorganized behavior,”10 and delusions or hallucinations.5,10 The patient should be asked specifically about unusual or bizarre thoughts or beliefs concerning the infant, in addition to thoughts of harming herself or others, particularly the infant.10

SCREENING

Numerous researchers have suggested that PPD is underrecognized and undertreated.5,6,18,27,28 Screening for PPD in the United States is not standardized and is highly variable.29 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports universal screening for PPD at the first postpartum visit, between two and six weeks.30,31 According to a 2010 Committee Opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “at this time, there is insufficient evidence to support a firm recommendation for universal antepartum or postpartum screening; however, screening for depression has the potential to benefit a woman and her family and should be strongly considered.”32

As the AHRQ14 notes, symptoms of PPD may not peak in some women until after their first postpartum visit, and providers of family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatric care may also be in a position to provide screening. The initial well-baby examination by the pediatric primary care provider, for example, presents an important opportunity to screen new mothers for PPD. According to Chaudron et al,33 the well-being of the infant should outweigh any scope-of-practice concerns, practitioner time limitations, or reimbursement issues; rather, screening efforts can be considered “tools to enhance [mothers’] ability to care for their children in a way that is supportive and not punitive.”33

In 2009, Sheeder and colleagues28 reported on a prospective study of 199 mothers in an adolescent maternity clinic who were screened using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)34 at each well-baby visit during the first six months postpartum. The authors concluded that the optimal time for screening for PPD in this setting is two months after delivery, although repeated screening may identify worsening of depressive symptoms.28

Several screening tools are available for the detection of PPD, particularly the EPDS,34 the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale,35 and the Patient Health Questionnaire–936-38 (see table,11,13,34-37 ). The EPDS, a widely used and well-validated formal screening tool,27,37 is a 10-item self-report questionnaire designed to detect depression in the postpartum period. Cox et al,34 who developed the scale, initially reported its sensitivity at 86% and specificity at 78%21; since then, the tool’s reported sensitivity for detecting major depression in the postpartum period has ranged from 60% to 96%, and specificity from 45% to 97%.6,39 The EPDS has been shown to result in a diagnosis of PPD in significantly more women than routine clinical evaluation (35.4% vs 6.3%, respectively).40 It is possible to administer the EPDS by telephone.41

The validity of the EPDS tool in detecting PPD was recently examined in a systematic review of 37 studies. Gibson et al42 concluded that the heterogeneity of these studies (ie, differences in study methodology, language used, and diagnostic criteria) precluded meta-analysis and did not provide clear support of EPDS as an accurate screening tool for PPD, especially across diverse cultures. In a similar review, Hewitt and colleagues6 sought to “provide an overview of all available methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care and to assess their validity.” They concluded that the EPDS is the most frequently reported screening tool and, with an overall sensitivity of 86% and overall specificity of 87%, its diagnostic performance seems “reasonably good.”6 Of note, fewer data have been collected to demonstrate the effectiveness of other screening tools.35,36,38,41

Cost-effectiveness is a consideration in the use of screening programs for PPD. According to a hypothetical cohort analysis conducted in the UK, the costs of treating women with false-positive screening results made implementation of a formal screening strategy for PPD not cost-effective, compared with usual care only, for use by the British National Health Service.43

MANAGEMENT

Once PPD is identified, treatment should be initiated as quickly as possible; referral for psychological counseling is an appropriate initial strategy for mild to moderate symptoms of PPD.5 A clinical care manager can be a valuable resource to provide education and coordination of care for women affected by PPD. NPs and PAs in primary care, obstetrics/gynecology, women’s health, and psychiatry or psychology can play an important role in the identification and management of PPD.

Treatment of PPD involves combination therapy—short-term psychological therapy combined with pharmacotherapy. According to investigators in a Cochrane Review of nine trials reporting short-term outcomes for 956 women with PPD, their findings suggest that psychosocial and psychological interventions are an effective option for reducing symptoms of PPD.44 Compared with usual care, the types of psychological therapy that were found most effective included cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and psychodynamic therapy. As most trials’ follow-up periods were limited to six months, however, neither the long-term effects of psychological therapy nor the relative effectiveness of each type of therapy was made clear by these studies.44,45

Pharmacotherapy

Although antidepressant drugs are known to be effective for the treatment of major depressive disorder, well-designed clinical trials demonstrating the overall effectiveness of antidepressants in treatment of PPD have been limited.46 According to Ng et al,46 who in 2010 performed a systematic review of studies examining pharmacologic interventions for PPD, preliminary evidence showing the effectiveness of antidepressants and hormone therapy should prompt the initiation of larger, more rigorous randomized and controlled trials.

The choice of antidepressants will be influenced by the mother’s breastfeeding status and whether PPD represents her first episode of depression or a recurrence of previous major depression. If the patient is not breastfeeding, the choice among antidepressants is similar to those used for treatment of nonpuerperal major depression. If PPD is a relapse of a prior depression, the therapeutic agent that was most effective and best-tolerated for previous depression should be prescribed.47

Generally, the SSRIs are considered first-line agents because of their superior safety profile.47 Fluoxetine has been shown in a small randomized trial (n = 87) to be significantly more effective than placebo and as effective as a full course of cognitive-behavioral counseling.45 In non–placebo-controlled studies, sertraline, fluvoxamine, and venlafaxine all produced improvement in PPD symptoms.48,49

Whether the mother is breastfeeding her infant will influence the use and choice of antidepressants for PPD. Although barely detectable levels of certain antidepressant medications (including the SSRIs sertraline and paroxetine, and the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline) have been reported in breast milk or in infant serum,50,51 it is recommended that the lowest possible therapeutic dose be prescribed, and that infants be carefully monitored for adverse effects.51

Fluoxetine, it should be noted, has been found to be transmitted through breast milk and was associated with reduced infant weight gain (specifically, by 392 g over six months) in a comparison between 64 fluoxetine-treated mothers and 38 non-treated mother-infant pairs.52 Thus, fluoxetine use should be avoided in women who are breastfeeding.

In small studies, paroxetine and fluvoxamine were not detected in infant serum, and although low levels of sertraline were detected in one-fourth of infants whose mothers received doses exceeding 100 mg/d, no adverse infant outcomes were noted.52-54 Paroxetine, nortriptyline, and sertraline appear to be relatively safer antidepressant choices in breastfeeding women with PPD.50,52,53

Antidepressants should be continued for six months after full remission of depressive symptoms. Longer courses of therapy may be necessary in patients who experience recurrent major depressive episodes.55

Few researchers have reported on the use of hormonal therapy for PPD. Yet significant hormonal fluctuations,56,57 including “estrogen withdrawal at parturition,”56 are known to occur after childbirth; in their study of women with severe PPD, Ahokas et al57 found that two-thirds of participants had serum estradiol concentrations below the cutoff for gonadal failure. Such a deficiency is likely to contribute to mood disturbances.56,57

In a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that enrolled women with severe, persistent PPD (mean EPDS score, 21.8), six months’ treatment with transdermally administered estradiol was associated with significantly greater relief of depressive symptoms than was found in controls (mean EPDS scores at one month, 13.3 vs 16.5, respectively). Of note, more than half of the women studied were concurrently receiving antidepressants.58

Additional studies may elucidate the role of estrogen therapy in the treatment of PPD.

Nonpharmacologic Options

An effective nonpharmacologic option for rapid resolution of severe symptoms of PPD is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).59-61 Its use is safe in nursing mothers because it does not affect breast milk. ECT is considered especially useful for women who have not responded to pharmacotherapy, those experiencing severe psychotic depression, and those who are considered at high risk for suicide or infanticide.

Patients typically receive three treatments per week; three to six treatments often produce an effective response.59 Anesthesia administered to women who undergo ECT has not been shown to have a negative effect on infants who are being breastfed.60,61

Interpersonal strategies to address PPD should not be overlooked. A pilot study conducted in Canada showed promising results when women who had previously experienced PPD were trained to provide peer support by telephone to mothers who were deemed at high risk for PPD (ie, those with EPDS scores > 12). At four weeks and eight weeks postpartum, follow-up EPDS scores exceeded 12 in 10% and 15%, respectively, of women receiving peer support, compared with 41% and 52%, respectively, of controls.62

Participation in one of numerous support groups that exist for women with PPD (see box, for online information) may reduce isolation in these women and possibly offer additional benefits.

COMPLICATIONS

PPD may be associated with significant complications, underscoring the importance of prompt identification and treatment.5 Maternal depressive symptoms in the critical postnatal period, for example, have been associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bonding. In one study of 101 women, lower-quality maternal bonding was found in women who had symptoms of depression at two weeks, six weeks, and four months postpartum—but not in those with depression at 14 months.63 Additionally, it was found in a systematic review of 49 studies that women with PPD were likely to discontinue breastfeeding earlier than women not affected.64

Delayed growth and development has been reported in infants of mothers with untreated or inadequately treated PPD.65 It has also been suggested that children of depressed mothers may have an increased risk for anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and other behavioral disorders later in childhood.65-67

PROGNOSIS

Untreated PPD may resolve spontaneously within three to six months, but in about one-quarter of PPD patients, depressive symptoms persist one year after delivery.24,68,69 PPD increases a woman’s risk for future episodes of major depression.2,5

PREVENTION

As previously discussed, the risk for PPD is greatest in women with a history of mood disorders (25%) and PPD (50%).2 Although several approaches have been studied to prevent PPD, no clear optimal strategy has been revealed. In one Cochrane review, insufficient evidence was found to justify prophylactic use of antidepressants.70 Similarly, findings in a second review fell short of confirming the effectiveness of prenatal psychosocial or psychological interventions to prevent antenatal depression.71

Additional studies are needed to make recommendations on prevention of PPD in high-risk patients. Until such recommendations emerge, close monitoring, screening, and follow-up are essential for these women.

CONCLUSION

Postpartum depression is an important concern among childbearing women, as it is associated with adverse maternal and infant outcomes. A personal history of depression is a major risk factor for PPD. It is imperative to question women about signs and symptoms of depression during the immediate postpartum period; it is particularly important to inquire about thoughts of harm to self or to the infant.

Pharmacotherapy combined with adjunctive psychological therapy is indicated for new mothers with significant depressive symptoms. The choice of antidepressants is based on previous response to antidepressants and the woman’s breastfeeding status. Generally, SSRIs are effective and well tolerated for major depression; based on results from small studies, they appear to be safe for breastfeeding mothers.

Electroconvulsive therapy is considered a safe and effective option for women with severe symptoms of PPD.

REFERENCES

1. Muzik M, Marcus SM, Heringhausen JE, Flynn H. When depression complicates childbearing: guidelines for screening and treatment during antenatal and postpartum obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36(4):771-788.

2. Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM. Clinical practice: postpartum depression. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):194-199.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

4. Whitton A, Warner R, Appleby L. The pathway to care in post-natal depression: women’s attitudes to post-natal depression and its treatment. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(408):427-428.

5. Sit DK, Wisner KL. Identification of postpartum depression. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 52(3):456-468.

6. Hewitt C, Gilbody S, Brealey S, et al. Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: an integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(36):1-145, 147-230.

7. Epperson CN. Postpartum major depression: detection and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(8):2247-2254, 2259-2260.

8. O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Wright EJ. Prospective study of postpartum blues: biologic and psychosocial factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):801-806.

9. Hannah P, Adams D, Lee A, et al. Links between early post-partum mood and post-natal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:777-780.

10. Sit D, Rothschild AJ, Wisner KL. A review of postpartum psychosis. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(4):352-368.

11. CDC. Prevalence of self-reported postpartum depressive symptoms—17 states, 2004–2005. MMWR Weekly. 2008;57(14):361-366.

12. O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:37-54.

13. Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439-445.

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Perinatal Depression: Prevalence, Screening Accuracy, and Screening Outcomes: Summary. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 119. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/peridep sum.htm. Accessed January 24, 2011.

15. Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2005 Feb;(119):1-8.

16. Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 106(5 pt 1):1071-1083.

17. Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, et al. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10): 1515-1520.

18. Almond P. Postnatal depression a global public health perspective. Perspect Public Health. 2009;129(5):221-227.

19. Lee D, Yip A, Chiu H, et al. A psychiatric epidemiological study of postpartum Chinese women. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):220-226.

20. Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, et al. Post-partum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:554-558.

21. McCoy SJB, Beal JM, Miller SBM, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depression: a retrospective investigation at 4-weeks postnatal and a review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(4):193-198.

22. Dennis CL, Janssen PA, Singer J. Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(5):338-346.

23. Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1-2):147-157.

24. Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Postpartum mood disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 suppl 2:34-40.

25. Corwin EJ, Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Low hemoglobin level is a risk factor for postpartum depression. J Nutr. 2003;133(12):4139-4142.

26. McCoy SJ, Beal JM, Payton ME, et al. Postpartum thyroid measures and depressive symptomology: a pilot study. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008;108(9):503-507.

27. Seehusen DA, Baldwin LM, Runkle GP, Clark G. Are family physicians appropriately screening for postpartum depression? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(2):104-112.

28. Sheeder J, Kabir K, Stafford B. Screening for postpartum depression at well-child visits: is once enough during the first 6 months of life? Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):e982-e988.

29. Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, Zlotnick C. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(4):357-364.

30. Shaver K. Treating postpartum depression during lactation. Prescriber’s Letter. 2001 Aug;8(8):47.

31. Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Wollan P, Yawn BP. Routine screening for postpartum depression. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(20):117-122.

32. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 453: Screening for depression during and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):394-395.

33. Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Campbell AT, et al. Legal and ethical considerations: risks and benefits of postpartum depression screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):123-128.

34. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782-786.

35. Beck CT, Gable RK. Postpartum Depression Screening Scale: development and psychometric testing. Nurs Res. 2000;49(5):272-282.

36. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders, Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999; 282(18):1737-44.

37. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

38. Yawn BP, Pace W, Wollan PC, et al. Concordance of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to assess increased risk of depression among postpartum women. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(5):483-491.

39. Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157: 288-290.

40. Evins GG, Theofrastous JP, Galvin SL. Postpartum depression: a comparison of screening and routine clinical evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(5):1080-1082.

41. Hanusa BH, Scholle SH, Haskett RF, et al. Screening for depression in the postpartum period: a comparison of three instruments. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(4):585-596.

42. Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, et al. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(5):350-364.

43. Paulden M, Palmer S, Hewitt C, Gilbody S. Screening for postnatal depression in primary care: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2009; 339:b5203.

44. Dennis CL,Hodnett ED. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006116.

45. Appleby L, Warner R, Whitton A, Faragher B. A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioural counselling in the treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ. 1997;314(7085): 932-936.

46. Ng RC, Hirata CK, Yeung W, et al. Pharmacologic treatment for postpartum depression: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2010; 30(9):928-941.

47. Whitby DH, Smith KM. The use of tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in women who are breastfeeding. Phamacotherapy. 2005;25(3):411-425.

48. Suri R, Burt VK, Altshuler LL, et al. Fluvoxamine for postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1739-1740.

49. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, Bouffard SM, et al. Venlafaxine in the treatment of postpartum depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(8):592-596.

50. Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Perel JM, et al. Postpartum depression: a randomized trial of sertraline versus nortriptyline. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(4):353-360.

51. Freeman MP. Postpartum depression treatment and breastfeeding. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;79(9):e35.

52. Gjerdingen D. The effectiveness of various postpartum depression treatments and the impact of antidepressant drugs on nursing infants. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(5): 372-382.

53. Wisner KL, Perel JM, Findling RL. Antidepressant treatment during breast-feeding. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(9):1132-1137.

54. Hendrick V, Fukuchi A, Altshuler L, et al. Use of sertraline, paroxetine and fluvoxamine by nursing women. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179: 163-166.

55. Davidson JR. Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in America and Europe.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71 suppl E1:e04.

56. Moses-Kolko EL, Berga SL, Kalro B, et al. Transdermal estradiol for postpartum depression: a promising treatment option. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52(3):516-529.

57. Ahokas A, Kaukoranta J, Wahlbeck K, Aito M. Estrogen deficiency in severe postpartum depression: successful treatment with sublingual physiologic 17beta-estradiol: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(5):

332-336.

58. Gregoire AJ, Kumar R, Everitt B, et al. Transdermal oestrogen for treatment of severe postnatal depression. Lancet. 1996;347(9006): 930-933.

59. Forray A, Ostroff RB. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in postpartum affective disorders. J ECT. 2007;23(3):188-193.

60. Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, et al. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(5):592-606.

61. Rabheru K. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in special patient populations. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(8):710-719.

62. Dennis CL. The effect of peer support on postpartum depression: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(2): 115-124.

63. Moehler E, Brunner R, Wiebel A, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bonding. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):273-278.

64. Dennis CL, McQueen K. The relationship between infant-feeding outcomes and postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e736-e751.

65. Hirst KP, Moutier CY. Postpartum major depression. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(8): 926-933.

66. Beck CT. The effects of postpartum depression on child development: a meta-analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1998;12(1):12-20.

67. Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1389-1398.

68. Cooper PJ, Murray L. Course and recurrence of postnatal depression: evidence for the specificity of the diagnostic concept. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(2):191-195.

69. Kumar R, Robson KM. A prospective study of emotional disorders in childbearing women. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:35-47.

70. Howard LM, Hoffbrand S, Henshaw C, et al. Antidepressant prevention of postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD00436.

71. Dennis CL, Ross LE, Grigoriadis S. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating antenatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD006309.

Care of the postpartum patient is an important component of primary care practice—particularly for clinicians who provide women’s health care and are called upon to effectively screen, identify, and manage patients who may be at risk for postpartum depression (PPD). Effective management of the postpartum patient also extends to care of her infant(s) and ideally should involve a multidisciplinary team, including the primary care provider, the pediatrician, and a psychologist or a psychiatrist.1

PPD is commonly described as depression that begins within the first month after delivery.2 It is diagnosed using the same criteria from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)3 as are used to identify major depressive disorder. According to the DSM-IV, PPD begins within the first four weeks after the infant’s birth.2,3 Although onset can occur at any time between 24 hours after a woman gives birth to several months later, PPD most commonly occurs within the first six weeks after delivery.1

The woman with PPD may be reluctant to report her symptoms for a number of reasons, including lack of motivation or energy, fatigue, embarrassment that she is experiencing such symptoms during a presumably happy time in her life—even fear that her child may be removed from her care.4 In addition to depressive symptoms (eg, sleeping difficulty, appetite changes, anhedonia, and guilt), women affected by PPD often experience anxiety and may become obsessed with the health, feeding, and sleeping behaviors of their infants.1,5

Postpartum mood disorders occur in a spectrum, ranging from postpartum baby blues to postpartum psychosis. By DSM-IV definition, a diagnosis of major or minor PPD requires that depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, or other characteristic symptoms be present most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks.3,6 PPD must be differentiated from the more common and less severe baby blues, which usually start two to three days after delivery and last less than two weeks.2,7 Between 40% and 80% of women who have given birth experience baby blues, which are characterized by transient mood swings, irritability, crying spells, difficulty sleeping, and difficulty concentrating.8 Experiencing baby blues may place women at increased risk for PPD.9

Postpartum, or puerperal, psychosis occurs in approximately 0.2% of women,10 with an early and sudden onset—that is, within the first week to four weeks postpartum. This severe condition is characterized by hallucinations and delusions often centered on the infant, in addition to insomnia, agitation, and extreme behavioral changes. Postpartum psychosis, which can recur in subsequent pregnancies, may be a manifestation of a preexisting affective disorder, such as bipolar disorder.10 Postpartum psychosis is considered an emergent condition because the safety and well-being of both mother and infant may be at serious risk.2,10

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

PPD is often cited as affecting 10% to 15% of women within the first year after childbirth.11,12 Currently, reported prevalence rates of PPD range from 5% to 20% of women who have recently given birth, depending on the source of information. Among 17 US states participating in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, a CDC surveillance project, prevalence of self-reported PPD symptoms ranged from 11.7% in Maine to 20.4% in New Mexico.11,13 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),14 the prevalence of major or minor depression ranges from 6.5% to 12.9% at different times during the year following delivery, although study design varied throughout the research used, and confidence intervals were deemed wide.14,15

Nevertheless, according to results from a systematic review of 28 studies, the prevalence of minor or major depression is estimated at up to 19.2% of women during the first three months postpartum, and major depression in up to 7% during that time.16 A 2007 chart review of 4,398 US women experiencing live births identified PPD in 10.4%.17

Incidence of PPD is “much higher than the quoted rate of 10% to 15%,” concludes Almond18 after a comprehensive literature review. The condition also affects women globally, the British researcher reports: Not only did she find numerous data on the incidence of PPD in high-income countries, including the US, the United Kingdom, and Australia, but she concluded that incidence rates of PPD in developing countries are grossly underestimated, according to epidemiologic studies in low- and middle-income countries (eg, Pakistan, Indonesia, Vietnam). Additionally, the risk factors for PPD are likely to be influenced by cultural differences, and attempts to identify PPD must be culturally sensitive.18

Several risk factors have been associated with PPD. Perhaps the most significant risk factor is a personal history of depression (prior to pregnancy or postpartum); at least one-half of women with PPD experience onset of depressive symptoms before or during their pregnancies,19,20 and one research group reported a relative risk (RR) of 1.87 for PPD in women with a history of depression, compared with those without such a history.21 Thus, women previously affected by depression should be carefully monitored in the immediate postpartum period for any signs of depressed mood, anxiety, sleep difficulties, loss of appetite or energy, and psychomotor changes.

According to McCoy et al,21 neither patient age nor marital status nor method of delivery appeared to be associated with PPD at four weeks postpartum. Women who were feeding by formula alone were more likely to experience PPD (RR, 2.04) than were those who breastfed their infants. Women who smoked were more likely to be affected by PPD (RR, 1.58) than were nonsmokers.

Additional risk factors for PPD identified by Dennis et al22 included pregnancy-induced hypertension and immigration within the previous five years. Various psychosocial stressors may also represent risk factors for PPD, including lack of social support, financial concerns, miscarriage or fetal demise, limited partner support, physical abuse before or during pregnancy, lack of readiness for hospital discharge, and complications during pregnancy and delivery (eg, low birth weight, premature birth, admission of the infant to the neonatal ICU).11,22,23

It is important to identify women who are at highest risk for PPD as soon as possible. High-risk patients should be screened upon discharge from the hospital and certainly on or before the first postpartum visit.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of PPD include depressed mood for at least two weeks with changes in somatic functions, such as sleep, energy level, appetite, weight, gastrointestinal functioning, and decrease in libido.3,24 These manifestations are more severe and prolonged than those associated with baby blues (which almost always resolve within two weeks postpartum).2,7

On physical examination, the patient with PPD may appear tearful and disheveled, with psychomotor retardation. She may report that she is unable to sleep even when her infant is sleeping, or that she has a significant lack of energy despite sufficient sleep; she may admit being unable to get out of bed for hours.2 The patient may report a significant decrease in appetite and little enjoyment in eating, which may lead to rapid weight loss.

Other symptoms may include obsessive thoughts about the infant and his or her care, significant anxiety (possibly manifested in panic attacks), uncontrollable crying, guilt, feelings of being overwhelmed or unable to care for the infant, mood swings, and severe irritability or even anger.2

Severe fatigue may warrant hemoglobin/hematocrit evaluation and possibly measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).25,26

It is essential to rule out postpartum psychosis, which is associated with prolonged lack of sleep, confusion, lapsed insight, cognitive impairment, “grossly disorganized behavior,”10 and delusions or hallucinations.5,10 The patient should be asked specifically about unusual or bizarre thoughts or beliefs concerning the infant, in addition to thoughts of harming herself or others, particularly the infant.10

SCREENING

Numerous researchers have suggested that PPD is underrecognized and undertreated.5,6,18,27,28 Screening for PPD in the United States is not standardized and is highly variable.29 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports universal screening for PPD at the first postpartum visit, between two and six weeks.30,31 According to a 2010 Committee Opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “at this time, there is insufficient evidence to support a firm recommendation for universal antepartum or postpartum screening; however, screening for depression has the potential to benefit a woman and her family and should be strongly considered.”32

As the AHRQ14 notes, symptoms of PPD may not peak in some women until after their first postpartum visit, and providers of family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatric care may also be in a position to provide screening. The initial well-baby examination by the pediatric primary care provider, for example, presents an important opportunity to screen new mothers for PPD. According to Chaudron et al,33 the well-being of the infant should outweigh any scope-of-practice concerns, practitioner time limitations, or reimbursement issues; rather, screening efforts can be considered “tools to enhance [mothers’] ability to care for their children in a way that is supportive and not punitive.”33

In 2009, Sheeder and colleagues28 reported on a prospective study of 199 mothers in an adolescent maternity clinic who were screened using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)34 at each well-baby visit during the first six months postpartum. The authors concluded that the optimal time for screening for PPD in this setting is two months after delivery, although repeated screening may identify worsening of depressive symptoms.28

Several screening tools are available for the detection of PPD, particularly the EPDS,34 the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale,35 and the Patient Health Questionnaire–936-38 (see table,11,13,34-37 ). The EPDS, a widely used and well-validated formal screening tool,27,37 is a 10-item self-report questionnaire designed to detect depression in the postpartum period. Cox et al,34 who developed the scale, initially reported its sensitivity at 86% and specificity at 78%21; since then, the tool’s reported sensitivity for detecting major depression in the postpartum period has ranged from 60% to 96%, and specificity from 45% to 97%.6,39 The EPDS has been shown to result in a diagnosis of PPD in significantly more women than routine clinical evaluation (35.4% vs 6.3%, respectively).40 It is possible to administer the EPDS by telephone.41

The validity of the EPDS tool in detecting PPD was recently examined in a systematic review of 37 studies. Gibson et al42 concluded that the heterogeneity of these studies (ie, differences in study methodology, language used, and diagnostic criteria) precluded meta-analysis and did not provide clear support of EPDS as an accurate screening tool for PPD, especially across diverse cultures. In a similar review, Hewitt and colleagues6 sought to “provide an overview of all available methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care and to assess their validity.” They concluded that the EPDS is the most frequently reported screening tool and, with an overall sensitivity of 86% and overall specificity of 87%, its diagnostic performance seems “reasonably good.”6 Of note, fewer data have been collected to demonstrate the effectiveness of other screening tools.35,36,38,41

Cost-effectiveness is a consideration in the use of screening programs for PPD. According to a hypothetical cohort analysis conducted in the UK, the costs of treating women with false-positive screening results made implementation of a formal screening strategy for PPD not cost-effective, compared with usual care only, for use by the British National Health Service.43

MANAGEMENT

Once PPD is identified, treatment should be initiated as quickly as possible; referral for psychological counseling is an appropriate initial strategy for mild to moderate symptoms of PPD.5 A clinical care manager can be a valuable resource to provide education and coordination of care for women affected by PPD. NPs and PAs in primary care, obstetrics/gynecology, women’s health, and psychiatry or psychology can play an important role in the identification and management of PPD.