User login

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. F, age 42, says he has always been a very anxious person and has chronically found his worrying to negatively affect his life. He says that over the last month his anxiety has been “off the charts” and he is worrying “24/7” due to taking on new responsibilities at his job and his son being diagnosed with lupus. He says his constant worrying is significantly impairing his ability to focus at his job, and he is considering taking a mental health leave from work. His wife reports that she is extremely frustrated because Mr. F has been isolating himself from family and friends; he admits this is true and attributes it to being preoccupied by his worries.

Mr. F endorses chronic insomnia, muscle tension, and irritability associated with anxiety; these have all substantially worsened over the last month. He admits that recently he has occasionally thought it would be easier if he weren’t alive. Mr. F denies having problems with his energy or motivation levels and insists that he generally feels very anxious, but not depressed. He says he drinks 1 alcoholic drink per week and denies any other substance use. Mr. F is overweight and has slightly elevated cholesterol but denies any other health conditions. He takes melatonin to help him sleep but does not take any prescribed medications.

Although this vignette provides limited details, on the surface it appears that Mr. F is experiencing an exacerbation of chronic generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). However, in this article, I propose establishing a new diagnosis: “acute anxiety disorder,” which would encapsulate severe exacerbations of a pre-existing anxiety disorder. Among the patients I have encountered for whom this diagnosis would fit, most have pre-existing GAD or panic disorder.

A look at the differential diagnosis

It is important to determine whether Mr. F is using any substances or has a medical condition that could be contributing to his anxiety. Other psychiatric diagnoses that could be considered include:

Adjustment disorder. This diagnosis would make sense if Mr. F didn’t have an apparent chronic history of symptoms that meet criteria for GAD.

Major depressive disorder with anxious distress. Many patients experiencing a major depressive episode meet the criteria for the specifier “with anxious distress,” even those who do not have a comorbid anxiety disorder.1 However, it is not evident from this vignette that Mr. F is experiencing a major depressive episode.

Continue to: Panic disorder and GAD...

Panic disorder and GAD. It is possible for a patient with GAD to develop panic disorder, which, at times, occurs after experiencing significant life stressors. Panic disorder requires the presence of recurrent panic attacks. Mr. F describes experiencing chronic, intense symptoms of anxiety rather than the discreet episodes of acute symptoms that characterize panic attacks.

Acute stress disorder. This diagnosis involves psychological symptoms that occur in response to exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation. Mr. F was not exposed to any of these stressors.

Why this new diagnosis would be helpful

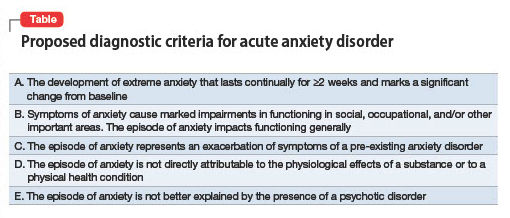

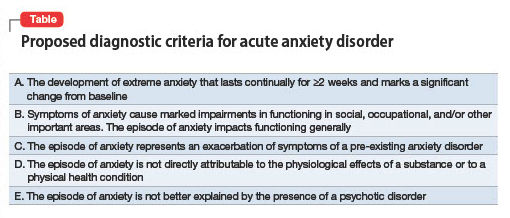

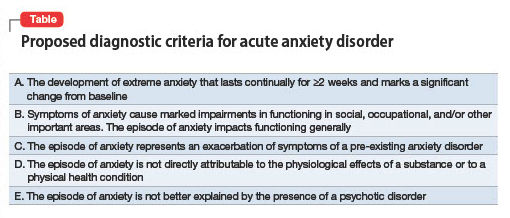

A new diagnosis, acute anxiety disorder, would indicate that a patient is currently experiencing an acute exacerbation of a chronic anxiety disorder that is leading to a significant decrease in their baseline functioning. My proposed criteria for acute anxiety disorder appear in the Table. Here are some reasons this diagnosis would be helpful:

Signifier of severity. Anxiety disorders such as GAD are generally not considered severe conditions and not considered to fall under the rubric of SPMI (severe and persistent mental illness).2 Posttraumatic stress disorder is the anxiety disorder–like condition most often found in the SPMI category. A diagnosis of acute anxiety disorder would indicate a patient is experiencing an episode of anxiety that is distinct from their chronic anxiety condition due to its severe impact on functional capabilities. Acute anxiety disorder would certainly not qualify as a “SPMI diagnosis” that would facilitate someone being considered eligible for supplemental security income, but it might be a legitimate justification for someone to receive short-term disability.

Treatment approach. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders usually involves a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). However, these medications can sometimes briefly increase anxiety when they are started. Individuals with acute anxiety are the most vulnerable to the possibility of experiencing increased anxiety when starting an SSRI or SNRI and may benefit from a slower titration of these medications. In light of this and the length of time required for SSRIs or SNRIs to exert a positive effect (typically a few weeks), patients with acute anxiety are best served by treatment with a medication with an immediate onset of action, such as a benzodiazepine or a sleep medication (eg, zolpidem). Benzodiazepines and hypnotics such as zolpidem are best prescribed for as-needed use because they carry a risk of dependence. One might consider prescribing mirtazapine or pregabalin (both of which are used off-label to treat anxiety) because these medications also have a relatively rapid onset of action and can treat both anxiety and insomnia (particularly mirtazapine).

Research considerations. It would be helpful to study which treatments are most effective for the subset of patients who experience acute anxiety disorder as I define it. Perhaps psychotherapy treatment protocols could be adapted or created. Treatment with esketamine or IV ketamine might be further studied as a treatment for acute anxiety because some evidence suggests ketamine is efficacious for this indication.3

1. Otsubo T, Hokama C, Sano N, et al. How significant is the assessment of the DSM-5 ‘anxious distress’ specifier in patients with major depressive disorder without comorbid anxiety disorders in the continuation/maintenance phase? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(4):385-392. doi:10.1080/13651501.2021.1907415

2. Butler H, O’Brien AJ. Access to specialist palliative care services by people with severe and persistent mental illness: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(2):737-746. doi:10.1111/inm.12360

3. Glue P, Neehoff SM, Medlicott NJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of maintenance ketamine treatment in patients with treatment-refractory generalised anxiety and social anxiety disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(6):663-667. doi:10.1177/0269881118762073

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. F, age 42, says he has always been a very anxious person and has chronically found his worrying to negatively affect his life. He says that over the last month his anxiety has been “off the charts” and he is worrying “24/7” due to taking on new responsibilities at his job and his son being diagnosed with lupus. He says his constant worrying is significantly impairing his ability to focus at his job, and he is considering taking a mental health leave from work. His wife reports that she is extremely frustrated because Mr. F has been isolating himself from family and friends; he admits this is true and attributes it to being preoccupied by his worries.

Mr. F endorses chronic insomnia, muscle tension, and irritability associated with anxiety; these have all substantially worsened over the last month. He admits that recently he has occasionally thought it would be easier if he weren’t alive. Mr. F denies having problems with his energy or motivation levels and insists that he generally feels very anxious, but not depressed. He says he drinks 1 alcoholic drink per week and denies any other substance use. Mr. F is overweight and has slightly elevated cholesterol but denies any other health conditions. He takes melatonin to help him sleep but does not take any prescribed medications.

Although this vignette provides limited details, on the surface it appears that Mr. F is experiencing an exacerbation of chronic generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). However, in this article, I propose establishing a new diagnosis: “acute anxiety disorder,” which would encapsulate severe exacerbations of a pre-existing anxiety disorder. Among the patients I have encountered for whom this diagnosis would fit, most have pre-existing GAD or panic disorder.

A look at the differential diagnosis

It is important to determine whether Mr. F is using any substances or has a medical condition that could be contributing to his anxiety. Other psychiatric diagnoses that could be considered include:

Adjustment disorder. This diagnosis would make sense if Mr. F didn’t have an apparent chronic history of symptoms that meet criteria for GAD.

Major depressive disorder with anxious distress. Many patients experiencing a major depressive episode meet the criteria for the specifier “with anxious distress,” even those who do not have a comorbid anxiety disorder.1 However, it is not evident from this vignette that Mr. F is experiencing a major depressive episode.

Continue to: Panic disorder and GAD...

Panic disorder and GAD. It is possible for a patient with GAD to develop panic disorder, which, at times, occurs after experiencing significant life stressors. Panic disorder requires the presence of recurrent panic attacks. Mr. F describes experiencing chronic, intense symptoms of anxiety rather than the discreet episodes of acute symptoms that characterize panic attacks.

Acute stress disorder. This diagnosis involves psychological symptoms that occur in response to exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation. Mr. F was not exposed to any of these stressors.

Why this new diagnosis would be helpful

A new diagnosis, acute anxiety disorder, would indicate that a patient is currently experiencing an acute exacerbation of a chronic anxiety disorder that is leading to a significant decrease in their baseline functioning. My proposed criteria for acute anxiety disorder appear in the Table. Here are some reasons this diagnosis would be helpful:

Signifier of severity. Anxiety disorders such as GAD are generally not considered severe conditions and not considered to fall under the rubric of SPMI (severe and persistent mental illness).2 Posttraumatic stress disorder is the anxiety disorder–like condition most often found in the SPMI category. A diagnosis of acute anxiety disorder would indicate a patient is experiencing an episode of anxiety that is distinct from their chronic anxiety condition due to its severe impact on functional capabilities. Acute anxiety disorder would certainly not qualify as a “SPMI diagnosis” that would facilitate someone being considered eligible for supplemental security income, but it might be a legitimate justification for someone to receive short-term disability.

Treatment approach. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders usually involves a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). However, these medications can sometimes briefly increase anxiety when they are started. Individuals with acute anxiety are the most vulnerable to the possibility of experiencing increased anxiety when starting an SSRI or SNRI and may benefit from a slower titration of these medications. In light of this and the length of time required for SSRIs or SNRIs to exert a positive effect (typically a few weeks), patients with acute anxiety are best served by treatment with a medication with an immediate onset of action, such as a benzodiazepine or a sleep medication (eg, zolpidem). Benzodiazepines and hypnotics such as zolpidem are best prescribed for as-needed use because they carry a risk of dependence. One might consider prescribing mirtazapine or pregabalin (both of which are used off-label to treat anxiety) because these medications also have a relatively rapid onset of action and can treat both anxiety and insomnia (particularly mirtazapine).

Research considerations. It would be helpful to study which treatments are most effective for the subset of patients who experience acute anxiety disorder as I define it. Perhaps psychotherapy treatment protocols could be adapted or created. Treatment with esketamine or IV ketamine might be further studied as a treatment for acute anxiety because some evidence suggests ketamine is efficacious for this indication.3

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. F, age 42, says he has always been a very anxious person and has chronically found his worrying to negatively affect his life. He says that over the last month his anxiety has been “off the charts” and he is worrying “24/7” due to taking on new responsibilities at his job and his son being diagnosed with lupus. He says his constant worrying is significantly impairing his ability to focus at his job, and he is considering taking a mental health leave from work. His wife reports that she is extremely frustrated because Mr. F has been isolating himself from family and friends; he admits this is true and attributes it to being preoccupied by his worries.

Mr. F endorses chronic insomnia, muscle tension, and irritability associated with anxiety; these have all substantially worsened over the last month. He admits that recently he has occasionally thought it would be easier if he weren’t alive. Mr. F denies having problems with his energy or motivation levels and insists that he generally feels very anxious, but not depressed. He says he drinks 1 alcoholic drink per week and denies any other substance use. Mr. F is overweight and has slightly elevated cholesterol but denies any other health conditions. He takes melatonin to help him sleep but does not take any prescribed medications.

Although this vignette provides limited details, on the surface it appears that Mr. F is experiencing an exacerbation of chronic generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). However, in this article, I propose establishing a new diagnosis: “acute anxiety disorder,” which would encapsulate severe exacerbations of a pre-existing anxiety disorder. Among the patients I have encountered for whom this diagnosis would fit, most have pre-existing GAD or panic disorder.

A look at the differential diagnosis

It is important to determine whether Mr. F is using any substances or has a medical condition that could be contributing to his anxiety. Other psychiatric diagnoses that could be considered include:

Adjustment disorder. This diagnosis would make sense if Mr. F didn’t have an apparent chronic history of symptoms that meet criteria for GAD.

Major depressive disorder with anxious distress. Many patients experiencing a major depressive episode meet the criteria for the specifier “with anxious distress,” even those who do not have a comorbid anxiety disorder.1 However, it is not evident from this vignette that Mr. F is experiencing a major depressive episode.

Continue to: Panic disorder and GAD...

Panic disorder and GAD. It is possible for a patient with GAD to develop panic disorder, which, at times, occurs after experiencing significant life stressors. Panic disorder requires the presence of recurrent panic attacks. Mr. F describes experiencing chronic, intense symptoms of anxiety rather than the discreet episodes of acute symptoms that characterize panic attacks.

Acute stress disorder. This diagnosis involves psychological symptoms that occur in response to exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation. Mr. F was not exposed to any of these stressors.

Why this new diagnosis would be helpful

A new diagnosis, acute anxiety disorder, would indicate that a patient is currently experiencing an acute exacerbation of a chronic anxiety disorder that is leading to a significant decrease in their baseline functioning. My proposed criteria for acute anxiety disorder appear in the Table. Here are some reasons this diagnosis would be helpful:

Signifier of severity. Anxiety disorders such as GAD are generally not considered severe conditions and not considered to fall under the rubric of SPMI (severe and persistent mental illness).2 Posttraumatic stress disorder is the anxiety disorder–like condition most often found in the SPMI category. A diagnosis of acute anxiety disorder would indicate a patient is experiencing an episode of anxiety that is distinct from their chronic anxiety condition due to its severe impact on functional capabilities. Acute anxiety disorder would certainly not qualify as a “SPMI diagnosis” that would facilitate someone being considered eligible for supplemental security income, but it might be a legitimate justification for someone to receive short-term disability.

Treatment approach. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders usually involves a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). However, these medications can sometimes briefly increase anxiety when they are started. Individuals with acute anxiety are the most vulnerable to the possibility of experiencing increased anxiety when starting an SSRI or SNRI and may benefit from a slower titration of these medications. In light of this and the length of time required for SSRIs or SNRIs to exert a positive effect (typically a few weeks), patients with acute anxiety are best served by treatment with a medication with an immediate onset of action, such as a benzodiazepine or a sleep medication (eg, zolpidem). Benzodiazepines and hypnotics such as zolpidem are best prescribed for as-needed use because they carry a risk of dependence. One might consider prescribing mirtazapine or pregabalin (both of which are used off-label to treat anxiety) because these medications also have a relatively rapid onset of action and can treat both anxiety and insomnia (particularly mirtazapine).

Research considerations. It would be helpful to study which treatments are most effective for the subset of patients who experience acute anxiety disorder as I define it. Perhaps psychotherapy treatment protocols could be adapted or created. Treatment with esketamine or IV ketamine might be further studied as a treatment for acute anxiety because some evidence suggests ketamine is efficacious for this indication.3

1. Otsubo T, Hokama C, Sano N, et al. How significant is the assessment of the DSM-5 ‘anxious distress’ specifier in patients with major depressive disorder without comorbid anxiety disorders in the continuation/maintenance phase? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(4):385-392. doi:10.1080/13651501.2021.1907415

2. Butler H, O’Brien AJ. Access to specialist palliative care services by people with severe and persistent mental illness: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(2):737-746. doi:10.1111/inm.12360

3. Glue P, Neehoff SM, Medlicott NJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of maintenance ketamine treatment in patients with treatment-refractory generalised anxiety and social anxiety disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(6):663-667. doi:10.1177/0269881118762073

1. Otsubo T, Hokama C, Sano N, et al. How significant is the assessment of the DSM-5 ‘anxious distress’ specifier in patients with major depressive disorder without comorbid anxiety disorders in the continuation/maintenance phase? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(4):385-392. doi:10.1080/13651501.2021.1907415

2. Butler H, O’Brien AJ. Access to specialist palliative care services by people with severe and persistent mental illness: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(2):737-746. doi:10.1111/inm.12360

3. Glue P, Neehoff SM, Medlicott NJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of maintenance ketamine treatment in patients with treatment-refractory generalised anxiety and social anxiety disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(6):663-667. doi:10.1177/0269881118762073