User login

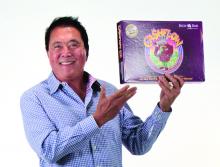

My son and I used to play a game called CASHFLOW. It was invented by Robert Kiyosaki, the real estate magnate who originated the “Rich Dad Poor Dad” book series to educate the masses on the basics of real estate investing.

The object of the game was to acquire enough passive income to become independent of active income like salary. The hope was that by playing the game, participants would recognize the advantages of passive income and become entrepreneurs in real estate or business. The winner was no longer an employee, but happily self-employed and out of the rat race.

Alas, the lesson was lost on me and my son. Both of us are still very much in the rat race and dependent on salary.

But a rat race can be more than just a competitive quest for financial gain. In politics, the quest is more for power. In sports, the quest includes championships. In academic medicine – and hematology is usually practiced in an academic setting – the quest is often for power and prestige. Training for our hematologic quest began in high school.

In high school, superior grades were a given, but we also worked to excel in sports, extracurricular activities, and standardized tests in order to get into the best universities. The cycle was then repeated to allow entry into the best medical schools. The old adage that students who finished last in their medical school class are still addressed as “Doctor” notwithstanding, most of us pushed ourselves beyond good grades to volunteer work, research activities, and prestigious clerkships to ensure that we matched at the best residency programs. There, those inclined to hematology cozied up to influential faculty by helping with their research in order to obtain the cherished letter of recommendation that promised admission to the best fellowship program, where the cycle was again repeated in the hope of landing a position in the best academic medical center.

Through these pursuits, young recruits to medical academia are primed and ready to enter a rat race of individual accomplishment. The academic rat race is a particularly pernicious result of our training to be the best, and the “best” hematologists are found at the podium, not in the exam room.

Not content to be recognized for clinical excellence by their patients, academic hematologists often aspire more to be recognized for content expertise by their peers. Through the noble pursuit of advancing science, peer recognition bestows prestige and power in the form of promotions, grants, advisory boards, consultancies, and speaking opportunities all over the globe. For some, the academic rat race validates a life dedicated to being the best.

However, the demands of patient care can interfere with academic pursuits and stand as impediments to the march of science, with its attendant rewards in power and prestige. The most common complaint I get from my team is the inability to fully participate in all that is required to succeed academically because of clinical responsibilities. The difficulty is worsened when financial realities require even more time spent in the clinic to generate income. This makes it hard enough to keep a healthy balance between research and patient care. When the pressures of clinical and academic hematology are combined with the responsibility of family, the rat race can begin to lead to burnout.

A rat race forces us to compare ourselves to others, and we often find ourselves wanting. There is always someone who seems wealthier and wiser than we are. Our training often compels us to compete with whoever it is we are comparing ourselves to. That competition simultaneously drives us toward a laudable goal and away from a balanced, happy life.

Theodore Roosevelt said “Comparison is the thief of joy,” and that certainly seems to be the case among medical professionals. As physicians, we do not lack for wealth, unless we compare ourselves to those who have more. We do not lack for wisdom, unless we compare ourselves to those who have more. We’d see that we really lack very little and occupy a privileged place in society if we only took the time to be grateful for having had the talent and support to do so.

I enjoyed playing CASHFLOW when I was younger and naively thought that either my son or I might materially benefit from its lessons. I realize now that the real enjoyment of playing was not to win or to get rich, but rather to spend time with my son. Likewise, our training got us where we are, and it will sustain a happy fulfilling career, but it will also consume us if we let go of why we started playing the game in the first place.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

My son and I used to play a game called CASHFLOW. It was invented by Robert Kiyosaki, the real estate magnate who originated the “Rich Dad Poor Dad” book series to educate the masses on the basics of real estate investing.

The object of the game was to acquire enough passive income to become independent of active income like salary. The hope was that by playing the game, participants would recognize the advantages of passive income and become entrepreneurs in real estate or business. The winner was no longer an employee, but happily self-employed and out of the rat race.

Alas, the lesson was lost on me and my son. Both of us are still very much in the rat race and dependent on salary.

But a rat race can be more than just a competitive quest for financial gain. In politics, the quest is more for power. In sports, the quest includes championships. In academic medicine – and hematology is usually practiced in an academic setting – the quest is often for power and prestige. Training for our hematologic quest began in high school.

In high school, superior grades were a given, but we also worked to excel in sports, extracurricular activities, and standardized tests in order to get into the best universities. The cycle was then repeated to allow entry into the best medical schools. The old adage that students who finished last in their medical school class are still addressed as “Doctor” notwithstanding, most of us pushed ourselves beyond good grades to volunteer work, research activities, and prestigious clerkships to ensure that we matched at the best residency programs. There, those inclined to hematology cozied up to influential faculty by helping with their research in order to obtain the cherished letter of recommendation that promised admission to the best fellowship program, where the cycle was again repeated in the hope of landing a position in the best academic medical center.

Through these pursuits, young recruits to medical academia are primed and ready to enter a rat race of individual accomplishment. The academic rat race is a particularly pernicious result of our training to be the best, and the “best” hematologists are found at the podium, not in the exam room.

Not content to be recognized for clinical excellence by their patients, academic hematologists often aspire more to be recognized for content expertise by their peers. Through the noble pursuit of advancing science, peer recognition bestows prestige and power in the form of promotions, grants, advisory boards, consultancies, and speaking opportunities all over the globe. For some, the academic rat race validates a life dedicated to being the best.

However, the demands of patient care can interfere with academic pursuits and stand as impediments to the march of science, with its attendant rewards in power and prestige. The most common complaint I get from my team is the inability to fully participate in all that is required to succeed academically because of clinical responsibilities. The difficulty is worsened when financial realities require even more time spent in the clinic to generate income. This makes it hard enough to keep a healthy balance between research and patient care. When the pressures of clinical and academic hematology are combined with the responsibility of family, the rat race can begin to lead to burnout.

A rat race forces us to compare ourselves to others, and we often find ourselves wanting. There is always someone who seems wealthier and wiser than we are. Our training often compels us to compete with whoever it is we are comparing ourselves to. That competition simultaneously drives us toward a laudable goal and away from a balanced, happy life.

Theodore Roosevelt said “Comparison is the thief of joy,” and that certainly seems to be the case among medical professionals. As physicians, we do not lack for wealth, unless we compare ourselves to those who have more. We do not lack for wisdom, unless we compare ourselves to those who have more. We’d see that we really lack very little and occupy a privileged place in society if we only took the time to be grateful for having had the talent and support to do so.

I enjoyed playing CASHFLOW when I was younger and naively thought that either my son or I might materially benefit from its lessons. I realize now that the real enjoyment of playing was not to win or to get rich, but rather to spend time with my son. Likewise, our training got us where we are, and it will sustain a happy fulfilling career, but it will also consume us if we let go of why we started playing the game in the first place.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

My son and I used to play a game called CASHFLOW. It was invented by Robert Kiyosaki, the real estate magnate who originated the “Rich Dad Poor Dad” book series to educate the masses on the basics of real estate investing.

The object of the game was to acquire enough passive income to become independent of active income like salary. The hope was that by playing the game, participants would recognize the advantages of passive income and become entrepreneurs in real estate or business. The winner was no longer an employee, but happily self-employed and out of the rat race.

Alas, the lesson was lost on me and my son. Both of us are still very much in the rat race and dependent on salary.

But a rat race can be more than just a competitive quest for financial gain. In politics, the quest is more for power. In sports, the quest includes championships. In academic medicine – and hematology is usually practiced in an academic setting – the quest is often for power and prestige. Training for our hematologic quest began in high school.

In high school, superior grades were a given, but we also worked to excel in sports, extracurricular activities, and standardized tests in order to get into the best universities. The cycle was then repeated to allow entry into the best medical schools. The old adage that students who finished last in their medical school class are still addressed as “Doctor” notwithstanding, most of us pushed ourselves beyond good grades to volunteer work, research activities, and prestigious clerkships to ensure that we matched at the best residency programs. There, those inclined to hematology cozied up to influential faculty by helping with their research in order to obtain the cherished letter of recommendation that promised admission to the best fellowship program, where the cycle was again repeated in the hope of landing a position in the best academic medical center.

Through these pursuits, young recruits to medical academia are primed and ready to enter a rat race of individual accomplishment. The academic rat race is a particularly pernicious result of our training to be the best, and the “best” hematologists are found at the podium, not in the exam room.

Not content to be recognized for clinical excellence by their patients, academic hematologists often aspire more to be recognized for content expertise by their peers. Through the noble pursuit of advancing science, peer recognition bestows prestige and power in the form of promotions, grants, advisory boards, consultancies, and speaking opportunities all over the globe. For some, the academic rat race validates a life dedicated to being the best.

However, the demands of patient care can interfere with academic pursuits and stand as impediments to the march of science, with its attendant rewards in power and prestige. The most common complaint I get from my team is the inability to fully participate in all that is required to succeed academically because of clinical responsibilities. The difficulty is worsened when financial realities require even more time spent in the clinic to generate income. This makes it hard enough to keep a healthy balance between research and patient care. When the pressures of clinical and academic hematology are combined with the responsibility of family, the rat race can begin to lead to burnout.

A rat race forces us to compare ourselves to others, and we often find ourselves wanting. There is always someone who seems wealthier and wiser than we are. Our training often compels us to compete with whoever it is we are comparing ourselves to. That competition simultaneously drives us toward a laudable goal and away from a balanced, happy life.

Theodore Roosevelt said “Comparison is the thief of joy,” and that certainly seems to be the case among medical professionals. As physicians, we do not lack for wealth, unless we compare ourselves to those who have more. We do not lack for wisdom, unless we compare ourselves to those who have more. We’d see that we really lack very little and occupy a privileged place in society if we only took the time to be grateful for having had the talent and support to do so.

I enjoyed playing CASHFLOW when I was younger and naively thought that either my son or I might materially benefit from its lessons. I realize now that the real enjoyment of playing was not to win or to get rich, but rather to spend time with my son. Likewise, our training got us where we are, and it will sustain a happy fulfilling career, but it will also consume us if we let go of why we started playing the game in the first place.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].