User login

THE CASE

Emily T.* is a 15-year-old, cisgender, homeless runaway. While on the streets, she was lured to a hotel where a “pimp” informed her she was going to work for him. She repeatedly tried to leave, but he would strike her, so she eventually succumbed. She was forced to have sex with several men and rarely allowed to use condoms.

On 1 occasion, when she went to a hospital with her pimp to visit a patient, her aunt (a nurse on duty at that facility) saw Ms. T and called the police. The pimp was arrested. Ms. T was interviewed by the police and gave a statement but refused a forensic exam.

Because of her involvement with the pimp, she was incarcerated. In prison, she was seen by a physician. On evaluation, she reported difficulty sleeping, flashbacks, and feelings of shame and guilt.1

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Child and adolescent sex trafficking is defined as the sexual exploitation of minors through force, fraud, or coercion. Specifically, it includes the recruitment, harboring, transportation, or advertising of a minor, and includes the exchange of anything of value in return for sexual activity. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking against minors include crimes such as prostitution; survival sex (exchanging sex/sexual acts for money or something of value, such as shelter, food, or drugs); pornography; sex tourism, mail-order-bride trade, and early marriage; or sexual performances (peep shows or strip clubs).2

Providing optimal care for children and adolescents exploited by sex trafficking depends on knowing risk factors, having an awareness of recommended screening and assessment tools, and employing a trauma-informed approach to interviews, examination, and support.2

Continue to: Recognize clues to trafficking

Recognize clues to trafficking

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a framework for trafficking prevention. Health care providers are encouraged to use the CDC Social-Ecological Model which describes targeted prevention strategies at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels.3

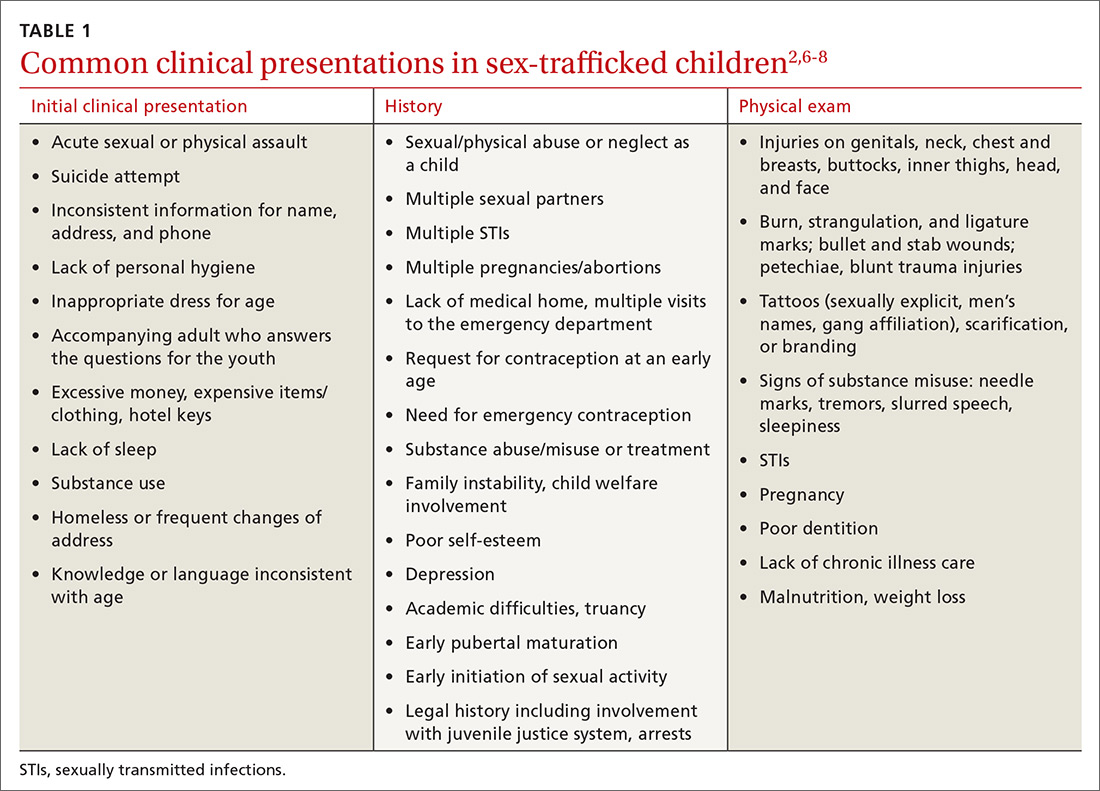

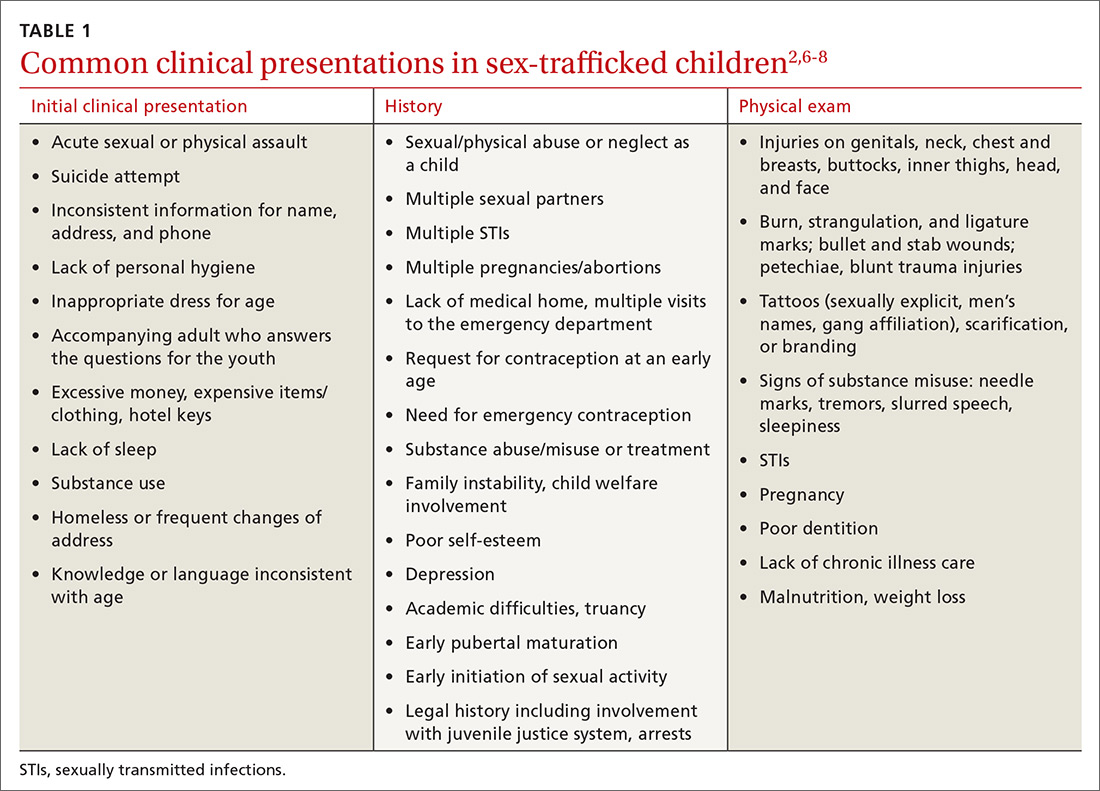

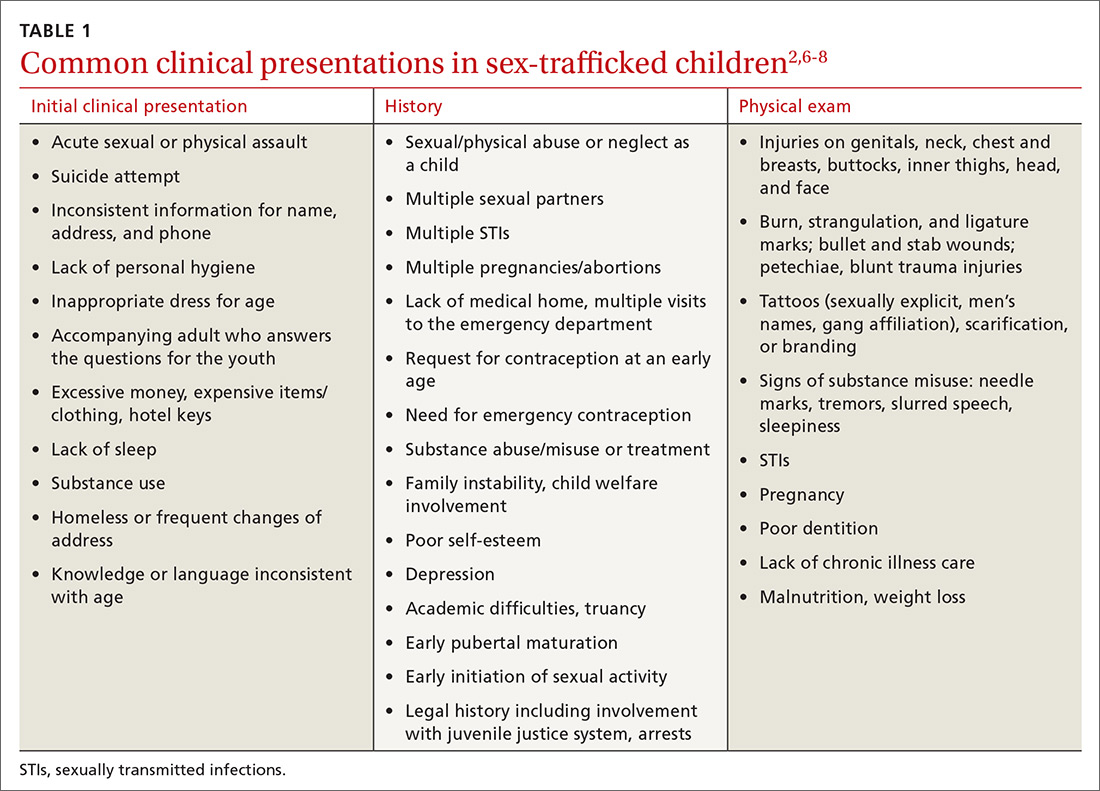

Risk factors for entering trafficking. Younger age increases a child’s vulnerability to exploitation, due to a lack of maturity, limited cognitive development, and ease of deception. The mean age of trafficking survivors is 15 years.4 History of child abuse and other traumatic experiences can lead children to run away from home. It is estimated that, once on the streets, most teens will be recruited by a trafficker within 48 hours.5 Poor self-esteem, depression, substance abuse, history of truancy, and early sexual maturation also increase the risk of becoming involved in trafficking (TABLE 1).2,6-8

Clinical findings suggestive of trafficking. Many physicians grasp the critical role they play in confronting trafficking, but they lack specific training, experience, and assessment tools.3 Notably, in 1 retrospective study, 46% of victims had been seen by a provider within the previous 2 months.6 One of the major challenges to identifying survivors of trafficking is to recognize critical signs, of which there are many (TABLE 12,6-8). Often these include a history of sexual assault, multiple pregnancies, requests for contraception at an early age, or evidence of physical injury.

Screen to identify trafficking

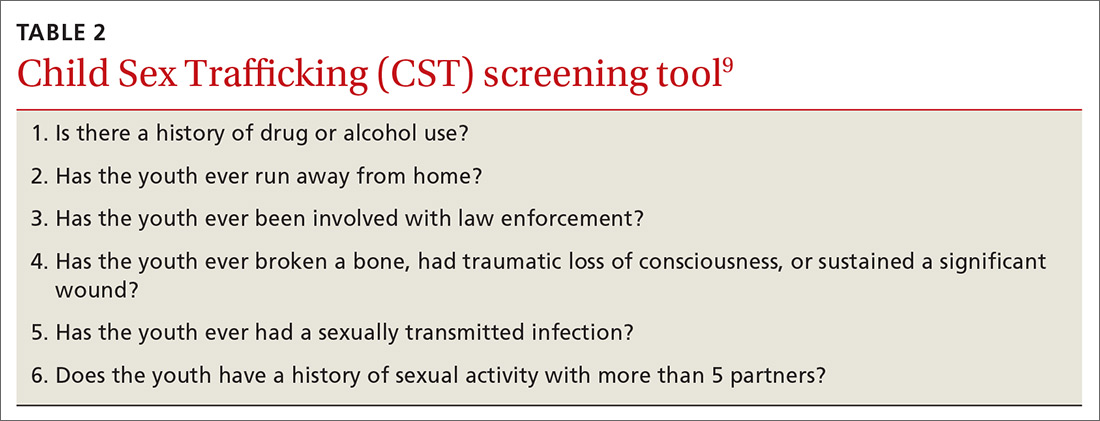

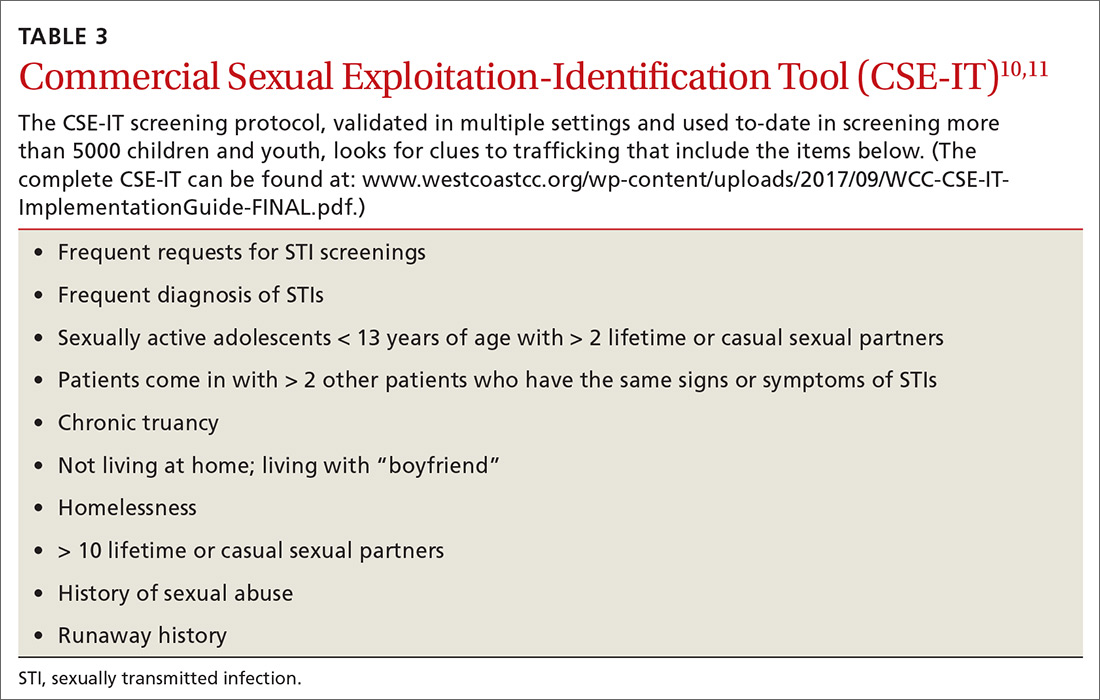

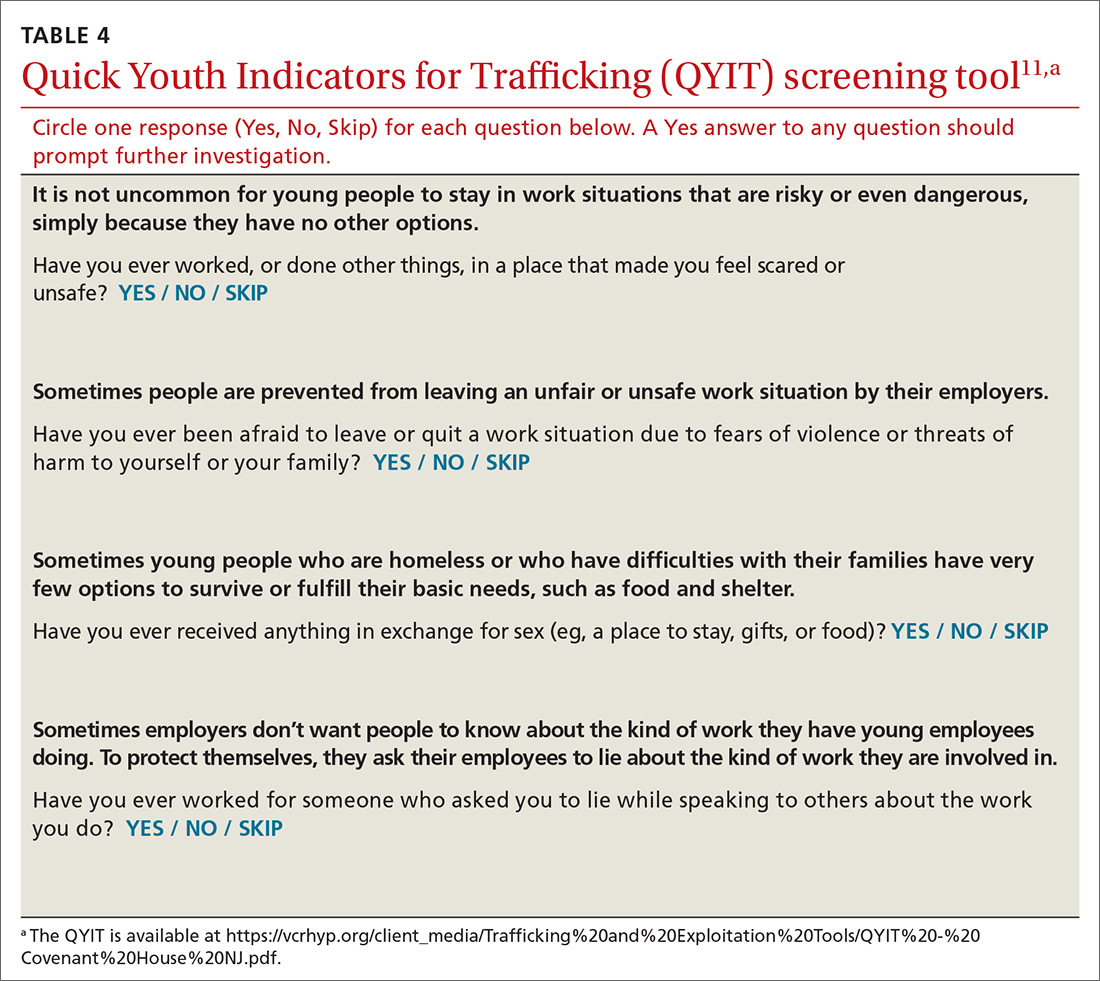

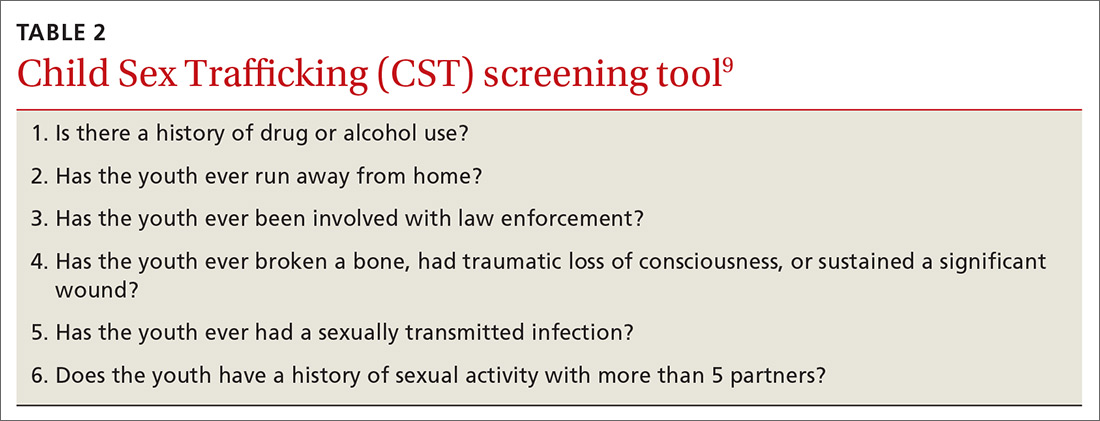

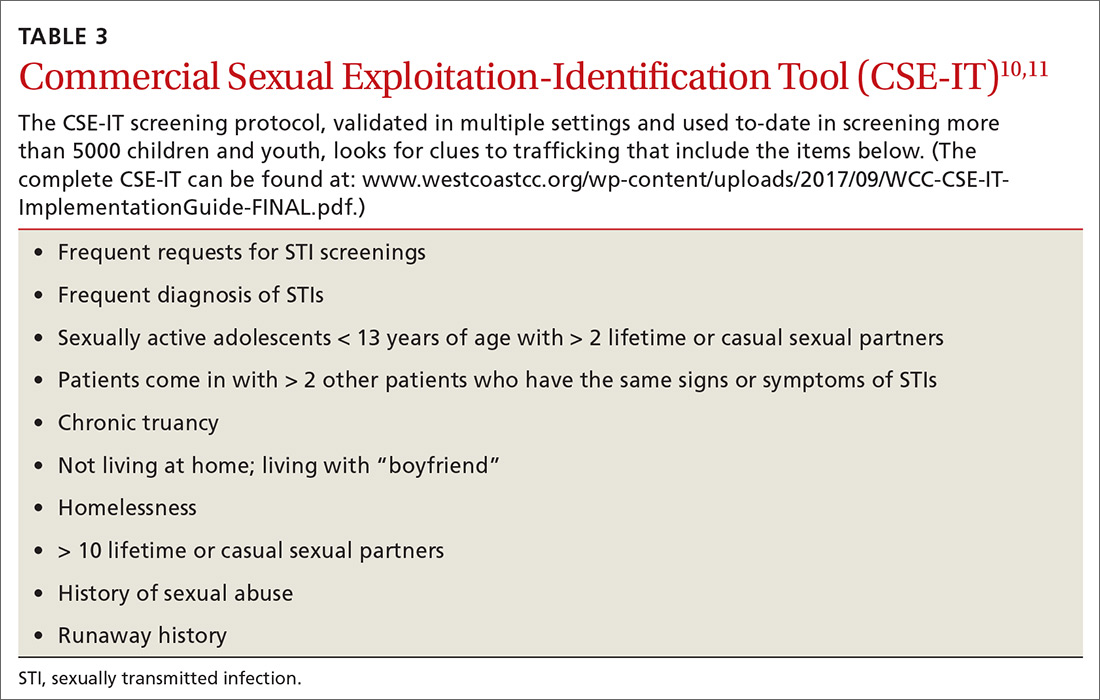

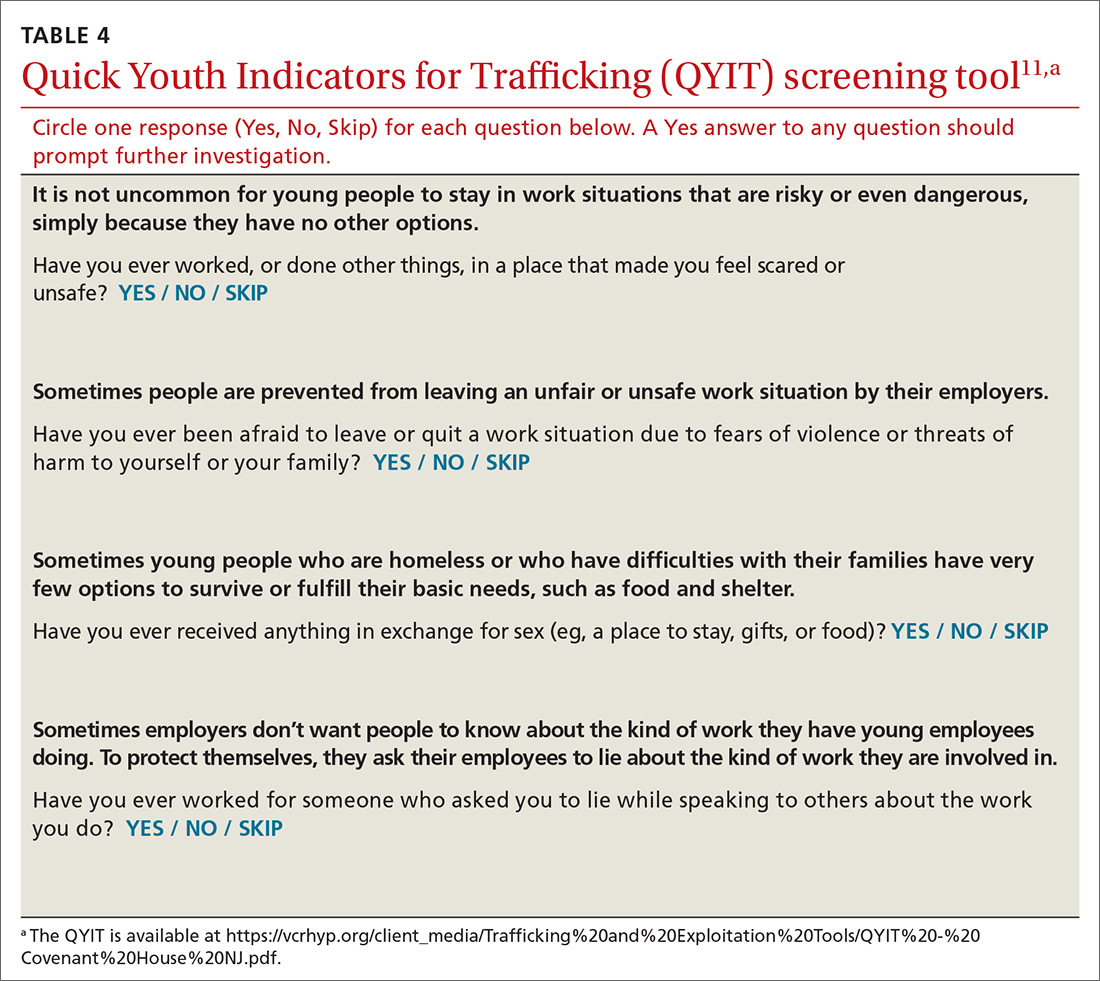

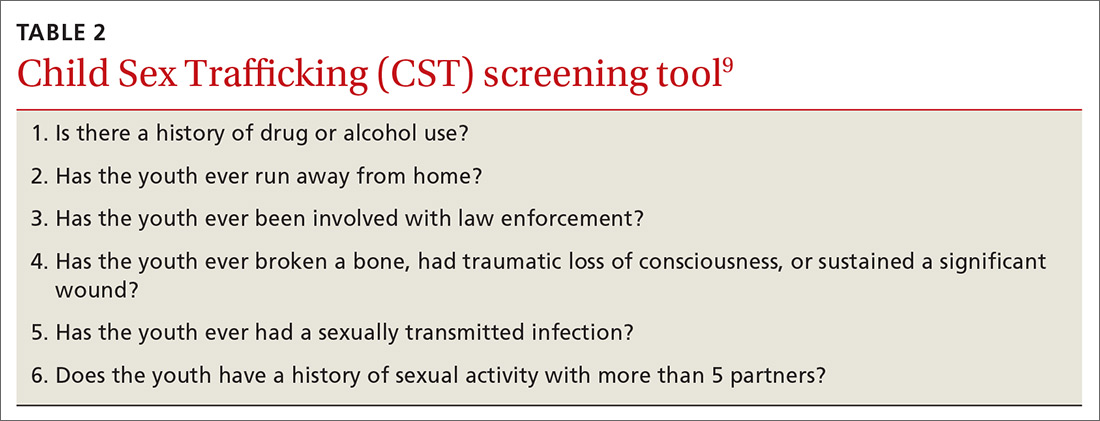

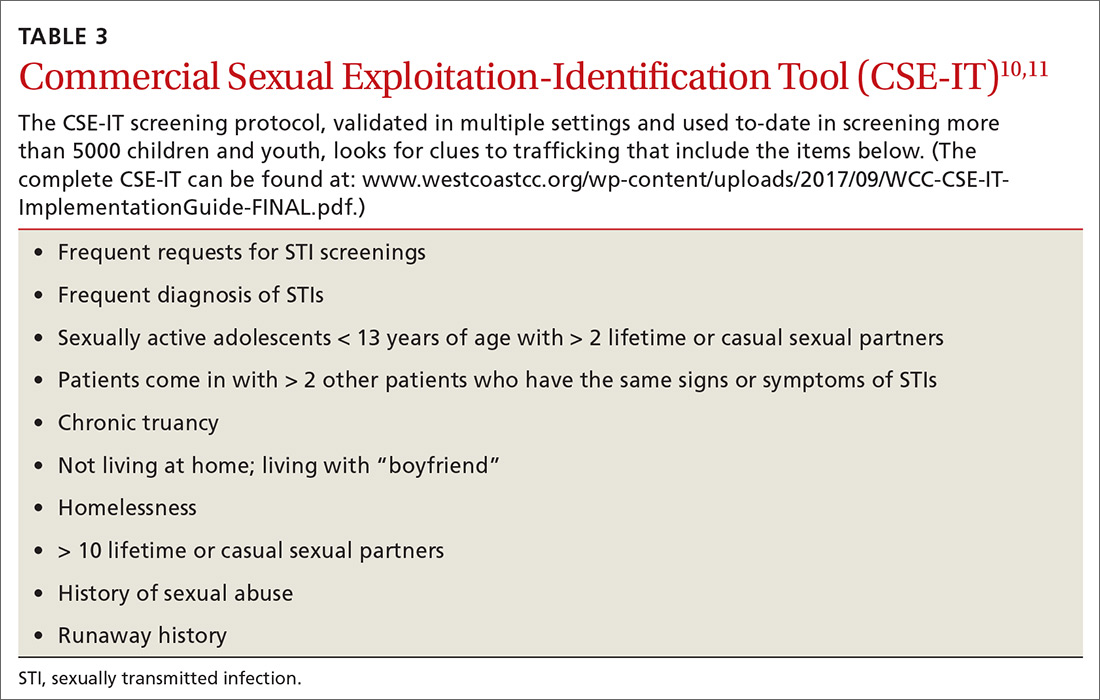

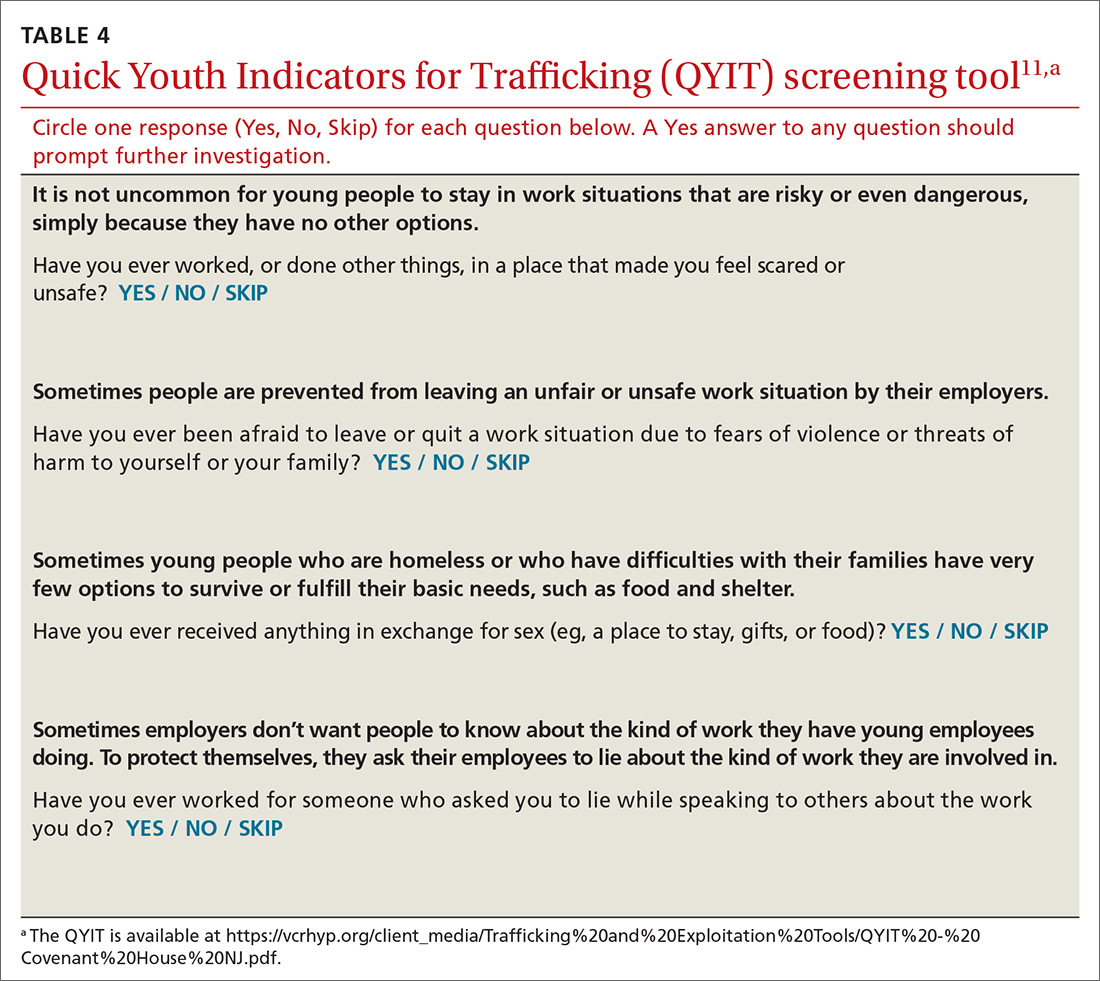

Universal, validated screening tools to accurately identify trafficked youth is an area of growing research. Some tools have been validated, but only for specific populations such as homeless or incarcerated youth or in emergency department (ED) patients. Tools for sex trafficking identification that may be useful in primary care include the Child Sex Trafficking (CST) screen validated in ED settings (TABLE 2),9 the Commercial Sexual Exploitation-Identification Tool (CSE-IT) in multiple settings (TABLE 3),10,11 and the Quick Youth Indicators for Trafficking (QYIT) in homeless youth (TABLE 4).11 The QYIT is the first validated labor and sex trafficking screening tool in homeless young adults. Children who screen positive for sex trafficking should be further assessed using a comprehensive tool.

Barriers to effective recognition of trafficked individuals. Financial factors limit access to health care. Also, survivors have cited multiple barriers for health professionals that prevent identification of survivors’ trafficked status.12,13 Once in the medical setting, disclosure is impacted by time constraints, fear of judgment by clinicians, and the risk of re-traumatization. Survivors have also cited lack of privacy, control strategies by their traffickers, lack of provider empathy, and fear of police as barriers to disclosure.14

Continue to: The medical impact of trafficking

The medical impact of trafficking

Sexual exploitation is a traumatic experience that is known to cause harm across multiple domains including serious physical injuries related to violence, as well as reproductive and mental health consequences.15,16

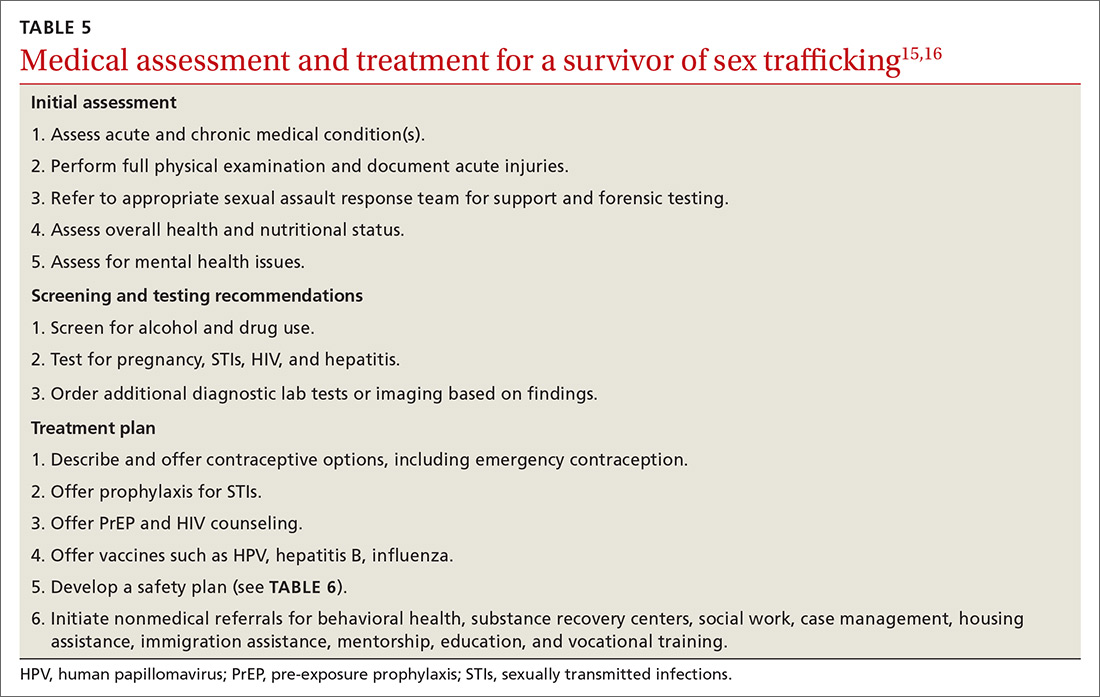

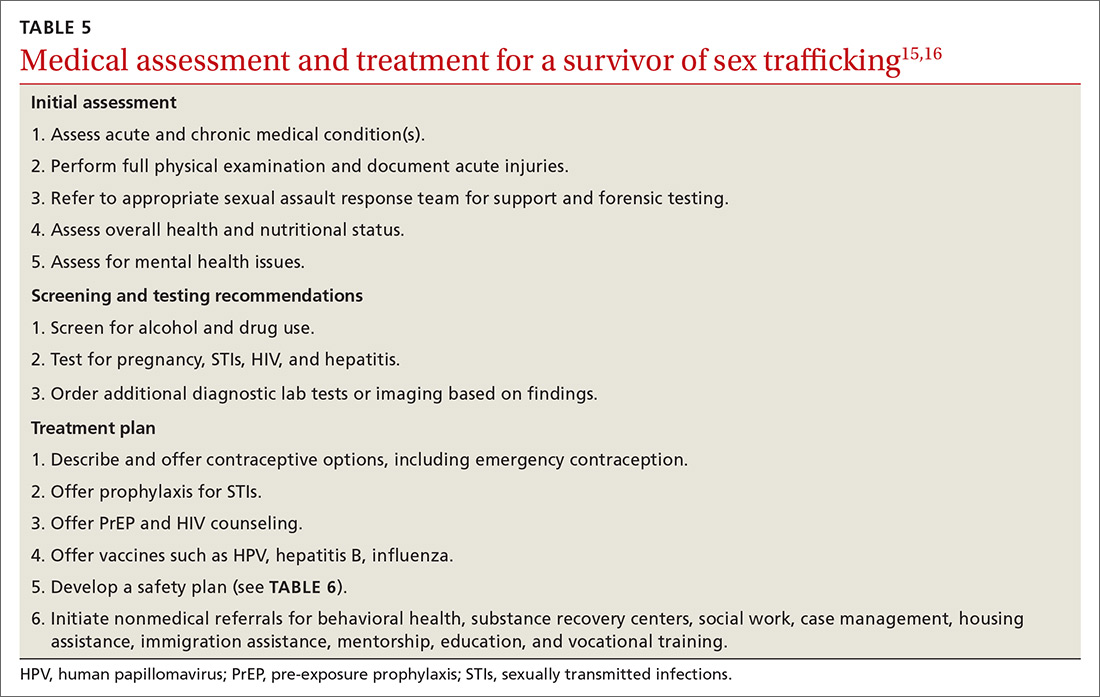

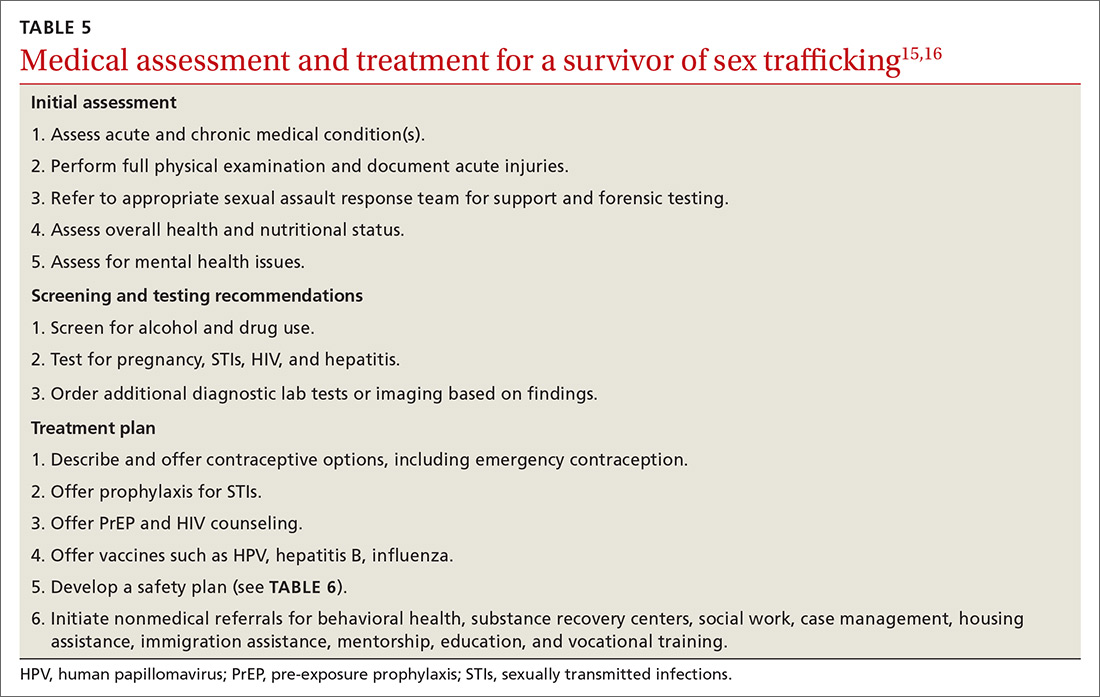

Acute and chronic illnesses. In an initial evaluation, assess the survivor’s acute medical conditions (TABLE 5).15,16 Common acute issues include physical injuries due to assault, infections, and reproductive complications.17 Health concerns can also result from stressors such as deprivation of food and sleep, hazardous living conditions, and limited access to care.17

As part of caring for sex-trafficking survivors, assess for, and treat, chronic health issues such as pain, gastrointestinal complaints, poor dental care, malnutrition, and fatigue.16,18 Substance use, as well as chronic mental health concerns (eg, anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) may also influence the clinical presentation.

Physical injuries. A cross-sectional study of female survivors of sex trafficking in the United States found that 89% sustained physical injury resulting from violence, including fractures, open wounds, head injury, dental problems, burns, and anogenital trauma.16,17 In many cases, acute injury may not be present in the clinical setting since care is often delayed, but a full examination can reveal signs of prior trauma.16

Reproductive health concerns. Significant, long-term impact on reproductive health can result due to forced penetration by multiple perpetrators, sodomy, and sex without protection or lubricants. Survivors are therefore at high risk for unplanned and unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pelvic pain, and infertility.16

Continue to: Psychological effects and trauma exposure

Psychological effects and trauma exposure. Survivors often have experienced abuse and neglect prior to commercial exploitation, and they may exhibit long-term sequelae. Survivors may present with major depression, anxiety, panic attacks, suicidality, addiction, PTSD, or aggression.16 Long-term sequelae for patients can include dysfunctional relationships due to an inability to trust, self-destructive behaviors, and significant shame.2,18

Care and treatment of trafficked youth

Initial presentation may occur in a variety of health care settings. Use a trauma-informed approach emphasizing physical and emotional safety and positive relationships, to reduce risk to the survivor, staff, and providers.19 Establishing trust and rapport may provide better short-term safety, as well as help build stronger long-term relationships that can lead to better health outcomes.

Clinical examination. Provide traumatized patients with a sense of safety, control, and autonomy in the health care setting. During the physical exam, be aware of the impact of re-traumatization as patients are asked to undress, endure sensitive examinations, and undergo invasive procedures. Explain the examination, ask for permission at each step, and use slow movements. Allow the patient to guide certain sensitive exams.15 Adopt an approach that recognizes the impact of trauma, avoids revictimization, and acknowledges the resilience of survivors.20

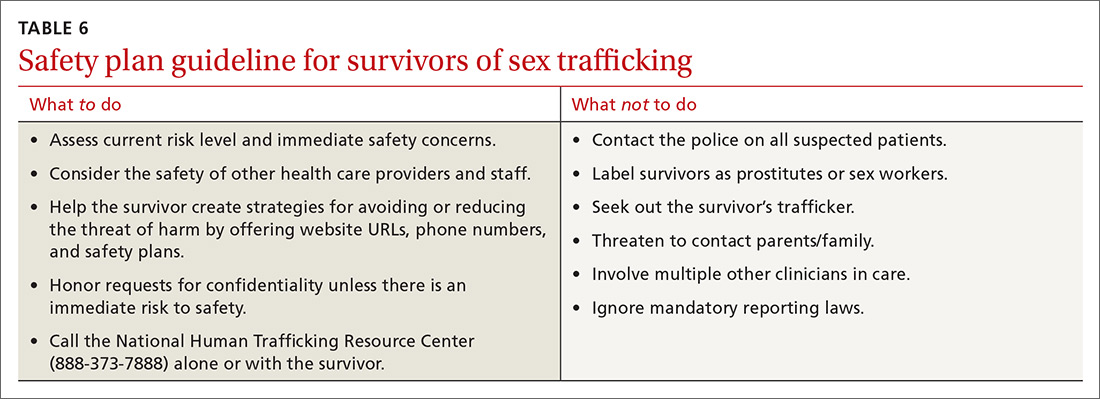

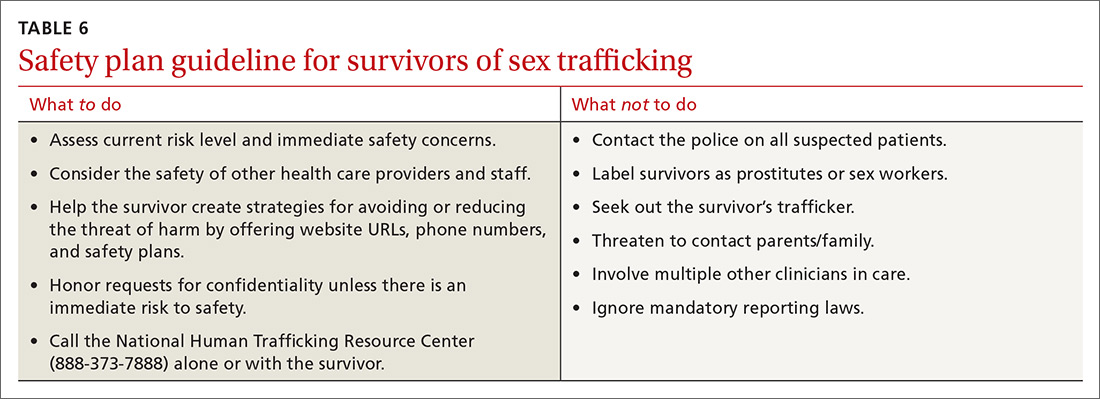

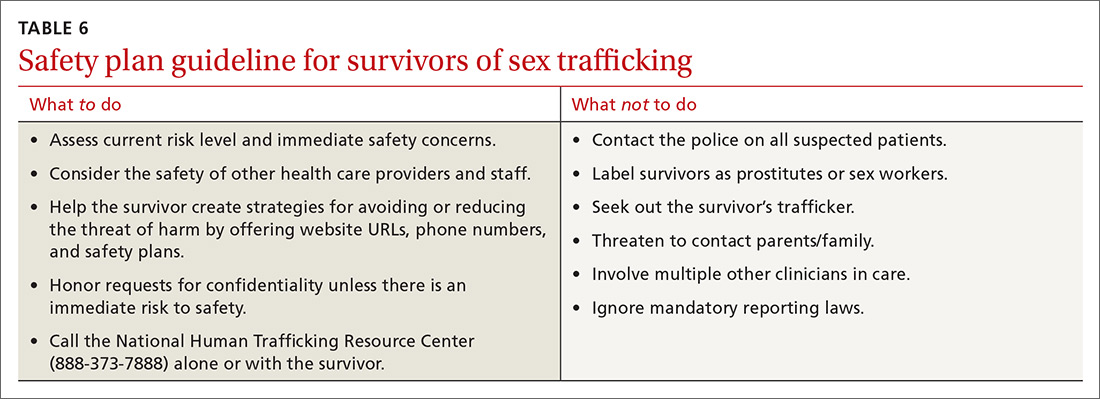

Treatment plan. After the initial exam, treat acute physical injuries and determine if any further testing is needed. Offer emergency contraception, STI prophylaxis, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and vaccines.15 After assessing patient readiness, offer local resources, identify safe methods for communication, identify individuals who could intervene in a crisis, and consider a safety plan (TABLE 6).

Coordination of care. Consider referrals to behavioral health services, substance recovery centers, food programs, housing resources, and a primary care clinic.15 ED clinicians may be asked to complete a sexual or physical assault forensic examination. After obtaining informed consent, one needs to19

- document skin signs such as scars, bites, strangulation marks, and tattoos. Note the size, shape, color, location, and other characteristics of each lesion.

- perform an oral, genital, and rectal examination and use a sexual assault evidence kit as indicated.

- use body diagrams and take photographs of all injuries/physical findings.

- order diagnostic testing as appropriate (eg, imaging to assess fractures).

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

During Ms. T’s incarceration, she was tested for STIs and treated for gonorrhea, trichomonas, and bacterial vaginosis. She was educated about sexual health, was counseled on contraception, and accepted condoms. She was referred to a therapist and given information on additional community resources she could contact upon her release.

A year after her release, she was incarcerated again. She also had an unplanned pregnancy. With the support she received from community programs, social workers, and her primary care provider, she moved in with her family, where she is currently living. She denies any ongoing trafficking activity.

CORRESPONDENCE

Piali Basu, DO, MPH, UCSF Primary Care, 185 Berry Street, Lobby 1, Suite 1000, San Francisco, CA 94107; [email protected]

1. Samko Tracey (Department of Pediatrics, LA County + University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA). Conversation with: Vidhi Doshi (Department of Internal Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA). July 8, 2019.

2. Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

3. Greenbaum VJ, Titchen K, Walker-Descartes I, et al. Multi-level prevention of human trafficking: the role of health care professionals. Prev Med. 2018;114:164-167.

4. Smith LA, Vardman SH, Snow MA. The national report on domestic minor sex trafficking: America’s prostituted children. 2009. Accessed January 11, 2021. http://sharedhope.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/SHI_National_Report_on_DMST_2009.pdf

5. Know the facts: commercial sexual exploitation of children. In: Connections. Summer 2011. Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs. Accessed January 11, 2021. www.wcsap.org/sites/default/files/uploads/resources_publications/connections/Commercial_Sexual_Exploitation_of_Youth_2011.pdf

6. Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C, et al. Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;44:98-105.

7. Walker K, California Child Welfare Council. Ending the commercial sexual exploitation of children: a call for multi-system collaboration in California. 2013. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://youthlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Ending-CSEC-A-Call-for-Multi-System_Collaboration-in-CA.pdf

8. Landers M, McGrath K, Johnson MH, et al. Baseline characteristics of dependent youth who have been commercially sexually exploited: findings from a specialized treatment program. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26:692-709.

9. Greenbaum VJ, Dodd M, McCracken C. A short screening tool to identify victims of child sex trafficking in the health care setting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:33-37.

10. Sy E, Quach T, Lee J, et al. Responding to commercially sexually exploited children (CSEC): a community health center‘s journey towards creating a primary care clinical CSEC screening tool in the United States. Inter J Soc Sci Stud. 2016;4:45-51.

11. Chisolm-Straker M, Sze J, Einbond J, et al. Screening for human trafficking among homeless young adults. Childr Youth Serv Rev. 2019;98:72-79.

12. Richie-Zavaleta AC, Villanueva A, Martinez-Donate A, et al. Sex trafficking victims at their junction with the healthcare setting—a mixed-methods inquiry. J Hum Traffick. 2020;6:1-29.

13. Chisolm-Straker M, Miller CL, Duke G, et al. A framework for the development of healthcare provider education programs on human trafficking part two: survivors. J Hum Traffick. 2019;5:410-424.

14. Heilemann T, Santhiveeran J. How do female adolescents cope and survive the hardships of prostitution? A content analysis of existing literature. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2011;20:57-76.

15. Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015;135:566-574.

16. Barnert E, Iqbal Z, Bruce J, et al. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of children and adolescents: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:825-829.

17. Dovydaitis T. Human trafficking: the role of the health care provider. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:462-467.

18. English A, Kivlahan C. Human rights and human trafficking of adolescents: legal and clinical perspectives. In: Titchen K, Miller E, Eds. Medical Perspectives on Human Trafficking in Adolescents. Springer Nature; 2020:21-41.

19. Price K, Nelson BD, Macias-Konstantopoulos WL. Understanding health care access disparities among human trafficking survivors: profiles of health care experiences, access, and engagement. J Interpers Violence. 2019; doi: 10.1177/0886260519889934.

20. Chambers R, Ravi A, Paulus S. Human trafficking: how family physicians can recognize and assist victims. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:202-204.

THE CASE

Emily T.* is a 15-year-old, cisgender, homeless runaway. While on the streets, she was lured to a hotel where a “pimp” informed her she was going to work for him. She repeatedly tried to leave, but he would strike her, so she eventually succumbed. She was forced to have sex with several men and rarely allowed to use condoms.

On 1 occasion, when she went to a hospital with her pimp to visit a patient, her aunt (a nurse on duty at that facility) saw Ms. T and called the police. The pimp was arrested. Ms. T was interviewed by the police and gave a statement but refused a forensic exam.

Because of her involvement with the pimp, she was incarcerated. In prison, she was seen by a physician. On evaluation, she reported difficulty sleeping, flashbacks, and feelings of shame and guilt.1

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Child and adolescent sex trafficking is defined as the sexual exploitation of minors through force, fraud, or coercion. Specifically, it includes the recruitment, harboring, transportation, or advertising of a minor, and includes the exchange of anything of value in return for sexual activity. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking against minors include crimes such as prostitution; survival sex (exchanging sex/sexual acts for money or something of value, such as shelter, food, or drugs); pornography; sex tourism, mail-order-bride trade, and early marriage; or sexual performances (peep shows or strip clubs).2

Providing optimal care for children and adolescents exploited by sex trafficking depends on knowing risk factors, having an awareness of recommended screening and assessment tools, and employing a trauma-informed approach to interviews, examination, and support.2

Continue to: Recognize clues to trafficking

Recognize clues to trafficking

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a framework for trafficking prevention. Health care providers are encouraged to use the CDC Social-Ecological Model which describes targeted prevention strategies at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels.3

Risk factors for entering trafficking. Younger age increases a child’s vulnerability to exploitation, due to a lack of maturity, limited cognitive development, and ease of deception. The mean age of trafficking survivors is 15 years.4 History of child abuse and other traumatic experiences can lead children to run away from home. It is estimated that, once on the streets, most teens will be recruited by a trafficker within 48 hours.5 Poor self-esteem, depression, substance abuse, history of truancy, and early sexual maturation also increase the risk of becoming involved in trafficking (TABLE 1).2,6-8

Clinical findings suggestive of trafficking. Many physicians grasp the critical role they play in confronting trafficking, but they lack specific training, experience, and assessment tools.3 Notably, in 1 retrospective study, 46% of victims had been seen by a provider within the previous 2 months.6 One of the major challenges to identifying survivors of trafficking is to recognize critical signs, of which there are many (TABLE 12,6-8). Often these include a history of sexual assault, multiple pregnancies, requests for contraception at an early age, or evidence of physical injury.

Screen to identify trafficking

Universal, validated screening tools to accurately identify trafficked youth is an area of growing research. Some tools have been validated, but only for specific populations such as homeless or incarcerated youth or in emergency department (ED) patients. Tools for sex trafficking identification that may be useful in primary care include the Child Sex Trafficking (CST) screen validated in ED settings (TABLE 2),9 the Commercial Sexual Exploitation-Identification Tool (CSE-IT) in multiple settings (TABLE 3),10,11 and the Quick Youth Indicators for Trafficking (QYIT) in homeless youth (TABLE 4).11 The QYIT is the first validated labor and sex trafficking screening tool in homeless young adults. Children who screen positive for sex trafficking should be further assessed using a comprehensive tool.

Barriers to effective recognition of trafficked individuals. Financial factors limit access to health care. Also, survivors have cited multiple barriers for health professionals that prevent identification of survivors’ trafficked status.12,13 Once in the medical setting, disclosure is impacted by time constraints, fear of judgment by clinicians, and the risk of re-traumatization. Survivors have also cited lack of privacy, control strategies by their traffickers, lack of provider empathy, and fear of police as barriers to disclosure.14

Continue to: The medical impact of trafficking

The medical impact of trafficking

Sexual exploitation is a traumatic experience that is known to cause harm across multiple domains including serious physical injuries related to violence, as well as reproductive and mental health consequences.15,16

Acute and chronic illnesses. In an initial evaluation, assess the survivor’s acute medical conditions (TABLE 5).15,16 Common acute issues include physical injuries due to assault, infections, and reproductive complications.17 Health concerns can also result from stressors such as deprivation of food and sleep, hazardous living conditions, and limited access to care.17

As part of caring for sex-trafficking survivors, assess for, and treat, chronic health issues such as pain, gastrointestinal complaints, poor dental care, malnutrition, and fatigue.16,18 Substance use, as well as chronic mental health concerns (eg, anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) may also influence the clinical presentation.

Physical injuries. A cross-sectional study of female survivors of sex trafficking in the United States found that 89% sustained physical injury resulting from violence, including fractures, open wounds, head injury, dental problems, burns, and anogenital trauma.16,17 In many cases, acute injury may not be present in the clinical setting since care is often delayed, but a full examination can reveal signs of prior trauma.16

Reproductive health concerns. Significant, long-term impact on reproductive health can result due to forced penetration by multiple perpetrators, sodomy, and sex without protection or lubricants. Survivors are therefore at high risk for unplanned and unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pelvic pain, and infertility.16

Continue to: Psychological effects and trauma exposure

Psychological effects and trauma exposure. Survivors often have experienced abuse and neglect prior to commercial exploitation, and they may exhibit long-term sequelae. Survivors may present with major depression, anxiety, panic attacks, suicidality, addiction, PTSD, or aggression.16 Long-term sequelae for patients can include dysfunctional relationships due to an inability to trust, self-destructive behaviors, and significant shame.2,18

Care and treatment of trafficked youth

Initial presentation may occur in a variety of health care settings. Use a trauma-informed approach emphasizing physical and emotional safety and positive relationships, to reduce risk to the survivor, staff, and providers.19 Establishing trust and rapport may provide better short-term safety, as well as help build stronger long-term relationships that can lead to better health outcomes.

Clinical examination. Provide traumatized patients with a sense of safety, control, and autonomy in the health care setting. During the physical exam, be aware of the impact of re-traumatization as patients are asked to undress, endure sensitive examinations, and undergo invasive procedures. Explain the examination, ask for permission at each step, and use slow movements. Allow the patient to guide certain sensitive exams.15 Adopt an approach that recognizes the impact of trauma, avoids revictimization, and acknowledges the resilience of survivors.20

Treatment plan. After the initial exam, treat acute physical injuries and determine if any further testing is needed. Offer emergency contraception, STI prophylaxis, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and vaccines.15 After assessing patient readiness, offer local resources, identify safe methods for communication, identify individuals who could intervene in a crisis, and consider a safety plan (TABLE 6).

Coordination of care. Consider referrals to behavioral health services, substance recovery centers, food programs, housing resources, and a primary care clinic.15 ED clinicians may be asked to complete a sexual or physical assault forensic examination. After obtaining informed consent, one needs to19

- document skin signs such as scars, bites, strangulation marks, and tattoos. Note the size, shape, color, location, and other characteristics of each lesion.

- perform an oral, genital, and rectal examination and use a sexual assault evidence kit as indicated.

- use body diagrams and take photographs of all injuries/physical findings.

- order diagnostic testing as appropriate (eg, imaging to assess fractures).

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

During Ms. T’s incarceration, she was tested for STIs and treated for gonorrhea, trichomonas, and bacterial vaginosis. She was educated about sexual health, was counseled on contraception, and accepted condoms. She was referred to a therapist and given information on additional community resources she could contact upon her release.

A year after her release, she was incarcerated again. She also had an unplanned pregnancy. With the support she received from community programs, social workers, and her primary care provider, she moved in with her family, where she is currently living. She denies any ongoing trafficking activity.

CORRESPONDENCE

Piali Basu, DO, MPH, UCSF Primary Care, 185 Berry Street, Lobby 1, Suite 1000, San Francisco, CA 94107; [email protected]

THE CASE

Emily T.* is a 15-year-old, cisgender, homeless runaway. While on the streets, she was lured to a hotel where a “pimp” informed her she was going to work for him. She repeatedly tried to leave, but he would strike her, so she eventually succumbed. She was forced to have sex with several men and rarely allowed to use condoms.

On 1 occasion, when she went to a hospital with her pimp to visit a patient, her aunt (a nurse on duty at that facility) saw Ms. T and called the police. The pimp was arrested. Ms. T was interviewed by the police and gave a statement but refused a forensic exam.

Because of her involvement with the pimp, she was incarcerated. In prison, she was seen by a physician. On evaluation, she reported difficulty sleeping, flashbacks, and feelings of shame and guilt.1

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Child and adolescent sex trafficking is defined as the sexual exploitation of minors through force, fraud, or coercion. Specifically, it includes the recruitment, harboring, transportation, or advertising of a minor, and includes the exchange of anything of value in return for sexual activity. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking against minors include crimes such as prostitution; survival sex (exchanging sex/sexual acts for money or something of value, such as shelter, food, or drugs); pornography; sex tourism, mail-order-bride trade, and early marriage; or sexual performances (peep shows or strip clubs).2

Providing optimal care for children and adolescents exploited by sex trafficking depends on knowing risk factors, having an awareness of recommended screening and assessment tools, and employing a trauma-informed approach to interviews, examination, and support.2

Continue to: Recognize clues to trafficking

Recognize clues to trafficking

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a framework for trafficking prevention. Health care providers are encouraged to use the CDC Social-Ecological Model which describes targeted prevention strategies at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels.3

Risk factors for entering trafficking. Younger age increases a child’s vulnerability to exploitation, due to a lack of maturity, limited cognitive development, and ease of deception. The mean age of trafficking survivors is 15 years.4 History of child abuse and other traumatic experiences can lead children to run away from home. It is estimated that, once on the streets, most teens will be recruited by a trafficker within 48 hours.5 Poor self-esteem, depression, substance abuse, history of truancy, and early sexual maturation also increase the risk of becoming involved in trafficking (TABLE 1).2,6-8

Clinical findings suggestive of trafficking. Many physicians grasp the critical role they play in confronting trafficking, but they lack specific training, experience, and assessment tools.3 Notably, in 1 retrospective study, 46% of victims had been seen by a provider within the previous 2 months.6 One of the major challenges to identifying survivors of trafficking is to recognize critical signs, of which there are many (TABLE 12,6-8). Often these include a history of sexual assault, multiple pregnancies, requests for contraception at an early age, or evidence of physical injury.

Screen to identify trafficking

Universal, validated screening tools to accurately identify trafficked youth is an area of growing research. Some tools have been validated, but only for specific populations such as homeless or incarcerated youth or in emergency department (ED) patients. Tools for sex trafficking identification that may be useful in primary care include the Child Sex Trafficking (CST) screen validated in ED settings (TABLE 2),9 the Commercial Sexual Exploitation-Identification Tool (CSE-IT) in multiple settings (TABLE 3),10,11 and the Quick Youth Indicators for Trafficking (QYIT) in homeless youth (TABLE 4).11 The QYIT is the first validated labor and sex trafficking screening tool in homeless young adults. Children who screen positive for sex trafficking should be further assessed using a comprehensive tool.

Barriers to effective recognition of trafficked individuals. Financial factors limit access to health care. Also, survivors have cited multiple barriers for health professionals that prevent identification of survivors’ trafficked status.12,13 Once in the medical setting, disclosure is impacted by time constraints, fear of judgment by clinicians, and the risk of re-traumatization. Survivors have also cited lack of privacy, control strategies by their traffickers, lack of provider empathy, and fear of police as barriers to disclosure.14

Continue to: The medical impact of trafficking

The medical impact of trafficking

Sexual exploitation is a traumatic experience that is known to cause harm across multiple domains including serious physical injuries related to violence, as well as reproductive and mental health consequences.15,16

Acute and chronic illnesses. In an initial evaluation, assess the survivor’s acute medical conditions (TABLE 5).15,16 Common acute issues include physical injuries due to assault, infections, and reproductive complications.17 Health concerns can also result from stressors such as deprivation of food and sleep, hazardous living conditions, and limited access to care.17

As part of caring for sex-trafficking survivors, assess for, and treat, chronic health issues such as pain, gastrointestinal complaints, poor dental care, malnutrition, and fatigue.16,18 Substance use, as well as chronic mental health concerns (eg, anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) may also influence the clinical presentation.

Physical injuries. A cross-sectional study of female survivors of sex trafficking in the United States found that 89% sustained physical injury resulting from violence, including fractures, open wounds, head injury, dental problems, burns, and anogenital trauma.16,17 In many cases, acute injury may not be present in the clinical setting since care is often delayed, but a full examination can reveal signs of prior trauma.16

Reproductive health concerns. Significant, long-term impact on reproductive health can result due to forced penetration by multiple perpetrators, sodomy, and sex without protection or lubricants. Survivors are therefore at high risk for unplanned and unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pelvic pain, and infertility.16

Continue to: Psychological effects and trauma exposure

Psychological effects and trauma exposure. Survivors often have experienced abuse and neglect prior to commercial exploitation, and they may exhibit long-term sequelae. Survivors may present with major depression, anxiety, panic attacks, suicidality, addiction, PTSD, or aggression.16 Long-term sequelae for patients can include dysfunctional relationships due to an inability to trust, self-destructive behaviors, and significant shame.2,18

Care and treatment of trafficked youth

Initial presentation may occur in a variety of health care settings. Use a trauma-informed approach emphasizing physical and emotional safety and positive relationships, to reduce risk to the survivor, staff, and providers.19 Establishing trust and rapport may provide better short-term safety, as well as help build stronger long-term relationships that can lead to better health outcomes.

Clinical examination. Provide traumatized patients with a sense of safety, control, and autonomy in the health care setting. During the physical exam, be aware of the impact of re-traumatization as patients are asked to undress, endure sensitive examinations, and undergo invasive procedures. Explain the examination, ask for permission at each step, and use slow movements. Allow the patient to guide certain sensitive exams.15 Adopt an approach that recognizes the impact of trauma, avoids revictimization, and acknowledges the resilience of survivors.20

Treatment plan. After the initial exam, treat acute physical injuries and determine if any further testing is needed. Offer emergency contraception, STI prophylaxis, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and vaccines.15 After assessing patient readiness, offer local resources, identify safe methods for communication, identify individuals who could intervene in a crisis, and consider a safety plan (TABLE 6).

Coordination of care. Consider referrals to behavioral health services, substance recovery centers, food programs, housing resources, and a primary care clinic.15 ED clinicians may be asked to complete a sexual or physical assault forensic examination. After obtaining informed consent, one needs to19

- document skin signs such as scars, bites, strangulation marks, and tattoos. Note the size, shape, color, location, and other characteristics of each lesion.

- perform an oral, genital, and rectal examination and use a sexual assault evidence kit as indicated.

- use body diagrams and take photographs of all injuries/physical findings.

- order diagnostic testing as appropriate (eg, imaging to assess fractures).

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

During Ms. T’s incarceration, she was tested for STIs and treated for gonorrhea, trichomonas, and bacterial vaginosis. She was educated about sexual health, was counseled on contraception, and accepted condoms. She was referred to a therapist and given information on additional community resources she could contact upon her release.

A year after her release, she was incarcerated again. She also had an unplanned pregnancy. With the support she received from community programs, social workers, and her primary care provider, she moved in with her family, where she is currently living. She denies any ongoing trafficking activity.

CORRESPONDENCE

Piali Basu, DO, MPH, UCSF Primary Care, 185 Berry Street, Lobby 1, Suite 1000, San Francisco, CA 94107; [email protected]

1. Samko Tracey (Department of Pediatrics, LA County + University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA). Conversation with: Vidhi Doshi (Department of Internal Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA). July 8, 2019.

2. Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

3. Greenbaum VJ, Titchen K, Walker-Descartes I, et al. Multi-level prevention of human trafficking: the role of health care professionals. Prev Med. 2018;114:164-167.

4. Smith LA, Vardman SH, Snow MA. The national report on domestic minor sex trafficking: America’s prostituted children. 2009. Accessed January 11, 2021. http://sharedhope.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/SHI_National_Report_on_DMST_2009.pdf

5. Know the facts: commercial sexual exploitation of children. In: Connections. Summer 2011. Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs. Accessed January 11, 2021. www.wcsap.org/sites/default/files/uploads/resources_publications/connections/Commercial_Sexual_Exploitation_of_Youth_2011.pdf

6. Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C, et al. Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;44:98-105.

7. Walker K, California Child Welfare Council. Ending the commercial sexual exploitation of children: a call for multi-system collaboration in California. 2013. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://youthlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Ending-CSEC-A-Call-for-Multi-System_Collaboration-in-CA.pdf

8. Landers M, McGrath K, Johnson MH, et al. Baseline characteristics of dependent youth who have been commercially sexually exploited: findings from a specialized treatment program. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26:692-709.

9. Greenbaum VJ, Dodd M, McCracken C. A short screening tool to identify victims of child sex trafficking in the health care setting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:33-37.

10. Sy E, Quach T, Lee J, et al. Responding to commercially sexually exploited children (CSEC): a community health center‘s journey towards creating a primary care clinical CSEC screening tool in the United States. Inter J Soc Sci Stud. 2016;4:45-51.

11. Chisolm-Straker M, Sze J, Einbond J, et al. Screening for human trafficking among homeless young adults. Childr Youth Serv Rev. 2019;98:72-79.

12. Richie-Zavaleta AC, Villanueva A, Martinez-Donate A, et al. Sex trafficking victims at their junction with the healthcare setting—a mixed-methods inquiry. J Hum Traffick. 2020;6:1-29.

13. Chisolm-Straker M, Miller CL, Duke G, et al. A framework for the development of healthcare provider education programs on human trafficking part two: survivors. J Hum Traffick. 2019;5:410-424.

14. Heilemann T, Santhiveeran J. How do female adolescents cope and survive the hardships of prostitution? A content analysis of existing literature. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2011;20:57-76.

15. Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015;135:566-574.

16. Barnert E, Iqbal Z, Bruce J, et al. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of children and adolescents: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:825-829.

17. Dovydaitis T. Human trafficking: the role of the health care provider. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:462-467.

18. English A, Kivlahan C. Human rights and human trafficking of adolescents: legal and clinical perspectives. In: Titchen K, Miller E, Eds. Medical Perspectives on Human Trafficking in Adolescents. Springer Nature; 2020:21-41.

19. Price K, Nelson BD, Macias-Konstantopoulos WL. Understanding health care access disparities among human trafficking survivors: profiles of health care experiences, access, and engagement. J Interpers Violence. 2019; doi: 10.1177/0886260519889934.

20. Chambers R, Ravi A, Paulus S. Human trafficking: how family physicians can recognize and assist victims. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:202-204.

1. Samko Tracey (Department of Pediatrics, LA County + University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA). Conversation with: Vidhi Doshi (Department of Internal Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA). July 8, 2019.

2. Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Confronting Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

3. Greenbaum VJ, Titchen K, Walker-Descartes I, et al. Multi-level prevention of human trafficking: the role of health care professionals. Prev Med. 2018;114:164-167.

4. Smith LA, Vardman SH, Snow MA. The national report on domestic minor sex trafficking: America’s prostituted children. 2009. Accessed January 11, 2021. http://sharedhope.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/SHI_National_Report_on_DMST_2009.pdf

5. Know the facts: commercial sexual exploitation of children. In: Connections. Summer 2011. Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs. Accessed January 11, 2021. www.wcsap.org/sites/default/files/uploads/resources_publications/connections/Commercial_Sexual_Exploitation_of_Youth_2011.pdf

6. Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C, et al. Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;44:98-105.

7. Walker K, California Child Welfare Council. Ending the commercial sexual exploitation of children: a call for multi-system collaboration in California. 2013. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://youthlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Ending-CSEC-A-Call-for-Multi-System_Collaboration-in-CA.pdf

8. Landers M, McGrath K, Johnson MH, et al. Baseline characteristics of dependent youth who have been commercially sexually exploited: findings from a specialized treatment program. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26:692-709.

9. Greenbaum VJ, Dodd M, McCracken C. A short screening tool to identify victims of child sex trafficking in the health care setting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:33-37.

10. Sy E, Quach T, Lee J, et al. Responding to commercially sexually exploited children (CSEC): a community health center‘s journey towards creating a primary care clinical CSEC screening tool in the United States. Inter J Soc Sci Stud. 2016;4:45-51.

11. Chisolm-Straker M, Sze J, Einbond J, et al. Screening for human trafficking among homeless young adults. Childr Youth Serv Rev. 2019;98:72-79.

12. Richie-Zavaleta AC, Villanueva A, Martinez-Donate A, et al. Sex trafficking victims at their junction with the healthcare setting—a mixed-methods inquiry. J Hum Traffick. 2020;6:1-29.

13. Chisolm-Straker M, Miller CL, Duke G, et al. A framework for the development of healthcare provider education programs on human trafficking part two: survivors. J Hum Traffick. 2019;5:410-424.

14. Heilemann T, Santhiveeran J. How do female adolescents cope and survive the hardships of prostitution? A content analysis of existing literature. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2011;20:57-76.

15. Greenbaum J, Crawford-Jakubiak JE, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: health care needs of victims. Pediatrics. 2015;135:566-574.

16. Barnert E, Iqbal Z, Bruce J, et al. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of children and adolescents: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:825-829.

17. Dovydaitis T. Human trafficking: the role of the health care provider. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:462-467.

18. English A, Kivlahan C. Human rights and human trafficking of adolescents: legal and clinical perspectives. In: Titchen K, Miller E, Eds. Medical Perspectives on Human Trafficking in Adolescents. Springer Nature; 2020:21-41.

19. Price K, Nelson BD, Macias-Konstantopoulos WL. Understanding health care access disparities among human trafficking survivors: profiles of health care experiences, access, and engagement. J Interpers Violence. 2019; doi: 10.1177/0886260519889934.

20. Chambers R, Ravi A, Paulus S. Human trafficking: how family physicians can recognize and assist victims. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:202-204.