User login

ORLANDO – Girls who undergo reduced-intensity conditioning for a bone marrow transplant may face fertility problems in the future, even if they experience an outwardly normal puberty.

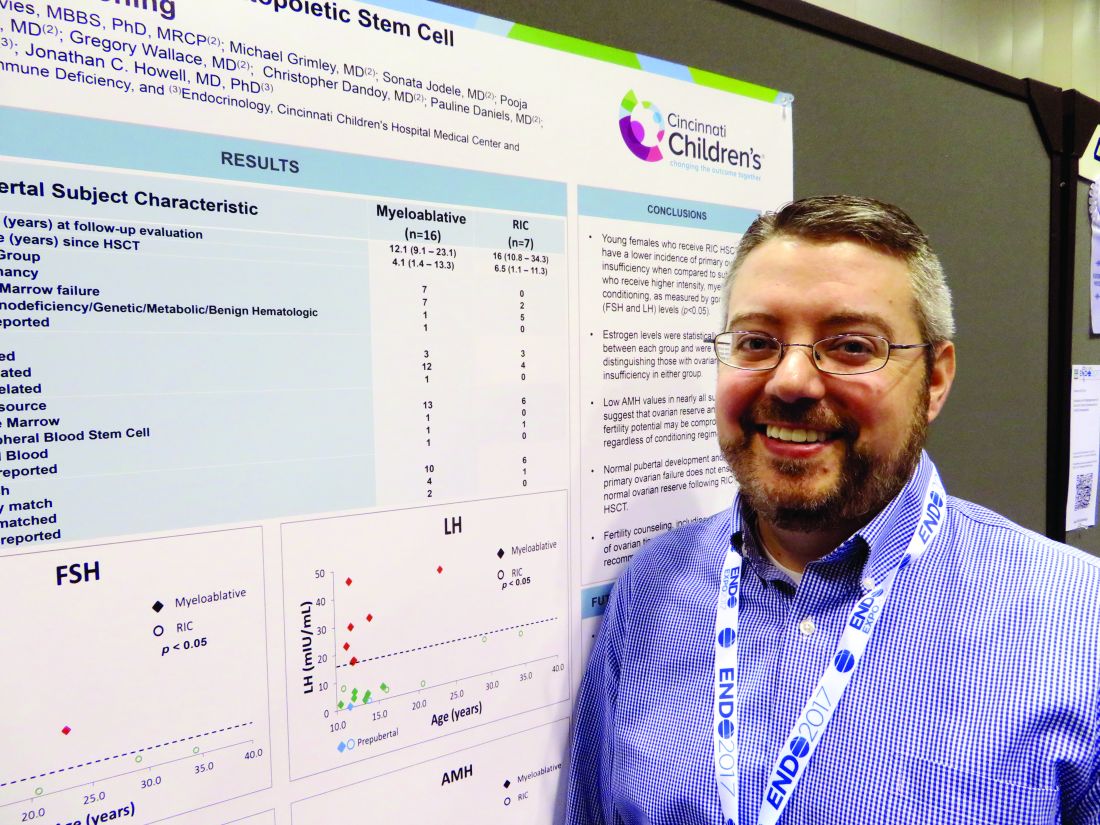

In the first-ever study to compare high- and low-intensity chemotherapeutic conditioning regimens among young girls, significantly more who underwent the reduced-intensity regimen had normal estradiol, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone compared with those who had high-intensity conditioning. But anti-Müllerian hormone was low or absent in almost all the girls, no matter which conditioning regimen they had, Jonathan C. Howell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

While not a perfect predictor of future fertility, anti-Müllerian hormone is a good indicator of ovarian follicular reserve, said Dr. Howell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Howell and his colleagues, Holly R. Hoefgen, MD, Kasiani C. Myers, MD, and Helen Oquendo-Del Toro, MD, all of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, are following 49 females aged 1-40 years who had preconditioning chemotherapy in advance of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

At the meeting, Dr. Howell reported data on 23 girls who were in puberty during their treatment (mean age 12 years). The mean follow-up was 4 years, but this varied widely, from 1 to 13 years. Most (16) had high-intensity myeloablation; the remainder had reduced-intensity conditioning. Diagnoses varied between the groups. Among those with high-intensity conditioning, malignancy and bone marrow failure were the most common indications (seven patients each); one patient had an immunodeficiency, and the cause was unknown for another.

Among those who had the reduced-intensity regimen, five had an immunodeficiency and two had bone marrow failure.

The discrepancy in diagnoses between the groups isn’t surprising, Dr. Howell said. “Diagnosis can dictate which treatment patients receive. People with malignancies or a prior history of leukemia or lymphoma often receive the high-intensity conditioning. You want to wipe out every single malignant cell.”

Reduced-intensity conditioning may be an option for patients with other problems such as bone marrow failure, immunodeficiencies, or genetic or metabolic problems. The less-intense regimen does confer some benefits, Dr. Howell noted. “The short-term need for intensive medical therapy while getting the stem cells is less. The medical benefit of these less-intense regimens is certainly there, but the long-term endocrine impact has yet to be defined.”

Most of the girls in the high-intensity regimen group (64%) had high follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, suggesting primary ovarian failure; 71% of them also had low estradiol levels. However, all of these hormones were normal in the reduced-intensity group. But regardless of conditioning treatment, anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low in nearly all of the patients (87%). Only one girl with myeloablative conditioning and two girls with reduced intensity condition had normal anti-Müllerian levels. “This tells us that fertility potential may not be preserved, despite [their] getting the reduced-intensity conditioning,” Dr. Howell said.

The story here is only beginning to unfold, he said. “Fertility is defined as the ability to conceive a child, and that’s not something we have looked at yet. We would like to know the long-term outcomes of fertility in these patients, and whether they can conceive when they’re ready to start a family. Our goal is to follow these young women into their 20s and 30s, and to see if that’s an opportunity they are able to experience.”

The study is a cooperative project involving the hospital’s divisions of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immunology, and Endocrinology.

Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.

Fertility preservation talks: The earlier, the better

A talk about fertility preservation can be the first step into a new future for families of children with a cancer diagnosis.

“Talking about your baby having a baby can be the farthest thing from your mind,” when you’re the parent of a child about to undergo cancer treatment, said Dr. Hoefgen. “But we know from survivors that this can be a very important issue in the future. We simply start by telling parents, ‘This will be important to your child at some point, and we want to talk about it now, while there is still something we may be able to do about it.’ ”

Dr. Hoefgen, a staff member at the hospital’s Comprehensive Fertility Care and Preservation Program, said parents “sometimes find it weird” to be talking about unborn grandchildren when they’re consumed with making critical decisions for their own child. But by asking them to consider that child’s long-term future, the discussion offers its own message of hope.

The talks always begin with a basic discussion of how cancer treatments can affect the reproductive organs. The hospital has a series of short animated videos that are very helpful in relaying the information. Another video in that series describes the different methods of fertility preservation: mature oocyte or sperm harvesting, or, for younger patients, removing and freezing ovarian and testicular tissue. Parents and children can watch them together, get grounding in the basics, and be prepared for a productive conversation.

Talks always include the team oncologist, who creates a specialized risk assessment for each patient. The group discusses each preservation method, the risks and benefits, and the cost. But the talks are exploratory, too, helping both clinicians and families understand what’s most important to them, she said.

“Common things that we typically talk about are genetics, religion, and ethics – which may mean different things to different families.”

Dr. Hoefgen and her team reach out to more than 95% of families that face a pediatric cancer diagnosis. After the in-depth discussions, she said, about 20% decide to investigate some form of fertility preservation.

“The most important thing is having the conversation early, while we still have options,” she said.

Dr. Hoefgen had no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Girls who undergo reduced-intensity conditioning for a bone marrow transplant may face fertility problems in the future, even if they experience an outwardly normal puberty.

In the first-ever study to compare high- and low-intensity chemotherapeutic conditioning regimens among young girls, significantly more who underwent the reduced-intensity regimen had normal estradiol, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone compared with those who had high-intensity conditioning. But anti-Müllerian hormone was low or absent in almost all the girls, no matter which conditioning regimen they had, Jonathan C. Howell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

While not a perfect predictor of future fertility, anti-Müllerian hormone is a good indicator of ovarian follicular reserve, said Dr. Howell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Howell and his colleagues, Holly R. Hoefgen, MD, Kasiani C. Myers, MD, and Helen Oquendo-Del Toro, MD, all of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, are following 49 females aged 1-40 years who had preconditioning chemotherapy in advance of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

At the meeting, Dr. Howell reported data on 23 girls who were in puberty during their treatment (mean age 12 years). The mean follow-up was 4 years, but this varied widely, from 1 to 13 years. Most (16) had high-intensity myeloablation; the remainder had reduced-intensity conditioning. Diagnoses varied between the groups. Among those with high-intensity conditioning, malignancy and bone marrow failure were the most common indications (seven patients each); one patient had an immunodeficiency, and the cause was unknown for another.

Among those who had the reduced-intensity regimen, five had an immunodeficiency and two had bone marrow failure.

The discrepancy in diagnoses between the groups isn’t surprising, Dr. Howell said. “Diagnosis can dictate which treatment patients receive. People with malignancies or a prior history of leukemia or lymphoma often receive the high-intensity conditioning. You want to wipe out every single malignant cell.”

Reduced-intensity conditioning may be an option for patients with other problems such as bone marrow failure, immunodeficiencies, or genetic or metabolic problems. The less-intense regimen does confer some benefits, Dr. Howell noted. “The short-term need for intensive medical therapy while getting the stem cells is less. The medical benefit of these less-intense regimens is certainly there, but the long-term endocrine impact has yet to be defined.”

Most of the girls in the high-intensity regimen group (64%) had high follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, suggesting primary ovarian failure; 71% of them also had low estradiol levels. However, all of these hormones were normal in the reduced-intensity group. But regardless of conditioning treatment, anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low in nearly all of the patients (87%). Only one girl with myeloablative conditioning and two girls with reduced intensity condition had normal anti-Müllerian levels. “This tells us that fertility potential may not be preserved, despite [their] getting the reduced-intensity conditioning,” Dr. Howell said.

The story here is only beginning to unfold, he said. “Fertility is defined as the ability to conceive a child, and that’s not something we have looked at yet. We would like to know the long-term outcomes of fertility in these patients, and whether they can conceive when they’re ready to start a family. Our goal is to follow these young women into their 20s and 30s, and to see if that’s an opportunity they are able to experience.”

The study is a cooperative project involving the hospital’s divisions of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immunology, and Endocrinology.

Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.

Fertility preservation talks: The earlier, the better

A talk about fertility preservation can be the first step into a new future for families of children with a cancer diagnosis.

“Talking about your baby having a baby can be the farthest thing from your mind,” when you’re the parent of a child about to undergo cancer treatment, said Dr. Hoefgen. “But we know from survivors that this can be a very important issue in the future. We simply start by telling parents, ‘This will be important to your child at some point, and we want to talk about it now, while there is still something we may be able to do about it.’ ”

Dr. Hoefgen, a staff member at the hospital’s Comprehensive Fertility Care and Preservation Program, said parents “sometimes find it weird” to be talking about unborn grandchildren when they’re consumed with making critical decisions for their own child. But by asking them to consider that child’s long-term future, the discussion offers its own message of hope.

The talks always begin with a basic discussion of how cancer treatments can affect the reproductive organs. The hospital has a series of short animated videos that are very helpful in relaying the information. Another video in that series describes the different methods of fertility preservation: mature oocyte or sperm harvesting, or, for younger patients, removing and freezing ovarian and testicular tissue. Parents and children can watch them together, get grounding in the basics, and be prepared for a productive conversation.

Talks always include the team oncologist, who creates a specialized risk assessment for each patient. The group discusses each preservation method, the risks and benefits, and the cost. But the talks are exploratory, too, helping both clinicians and families understand what’s most important to them, she said.

“Common things that we typically talk about are genetics, religion, and ethics – which may mean different things to different families.”

Dr. Hoefgen and her team reach out to more than 95% of families that face a pediatric cancer diagnosis. After the in-depth discussions, she said, about 20% decide to investigate some form of fertility preservation.

“The most important thing is having the conversation early, while we still have options,” she said.

Dr. Hoefgen had no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Girls who undergo reduced-intensity conditioning for a bone marrow transplant may face fertility problems in the future, even if they experience an outwardly normal puberty.

In the first-ever study to compare high- and low-intensity chemotherapeutic conditioning regimens among young girls, significantly more who underwent the reduced-intensity regimen had normal estradiol, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone compared with those who had high-intensity conditioning. But anti-Müllerian hormone was low or absent in almost all the girls, no matter which conditioning regimen they had, Jonathan C. Howell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

While not a perfect predictor of future fertility, anti-Müllerian hormone is a good indicator of ovarian follicular reserve, said Dr. Howell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Howell and his colleagues, Holly R. Hoefgen, MD, Kasiani C. Myers, MD, and Helen Oquendo-Del Toro, MD, all of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, are following 49 females aged 1-40 years who had preconditioning chemotherapy in advance of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

At the meeting, Dr. Howell reported data on 23 girls who were in puberty during their treatment (mean age 12 years). The mean follow-up was 4 years, but this varied widely, from 1 to 13 years. Most (16) had high-intensity myeloablation; the remainder had reduced-intensity conditioning. Diagnoses varied between the groups. Among those with high-intensity conditioning, malignancy and bone marrow failure were the most common indications (seven patients each); one patient had an immunodeficiency, and the cause was unknown for another.

Among those who had the reduced-intensity regimen, five had an immunodeficiency and two had bone marrow failure.

The discrepancy in diagnoses between the groups isn’t surprising, Dr. Howell said. “Diagnosis can dictate which treatment patients receive. People with malignancies or a prior history of leukemia or lymphoma often receive the high-intensity conditioning. You want to wipe out every single malignant cell.”

Reduced-intensity conditioning may be an option for patients with other problems such as bone marrow failure, immunodeficiencies, or genetic or metabolic problems. The less-intense regimen does confer some benefits, Dr. Howell noted. “The short-term need for intensive medical therapy while getting the stem cells is less. The medical benefit of these less-intense regimens is certainly there, but the long-term endocrine impact has yet to be defined.”

Most of the girls in the high-intensity regimen group (64%) had high follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, suggesting primary ovarian failure; 71% of them also had low estradiol levels. However, all of these hormones were normal in the reduced-intensity group. But regardless of conditioning treatment, anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low in nearly all of the patients (87%). Only one girl with myeloablative conditioning and two girls with reduced intensity condition had normal anti-Müllerian levels. “This tells us that fertility potential may not be preserved, despite [their] getting the reduced-intensity conditioning,” Dr. Howell said.

The story here is only beginning to unfold, he said. “Fertility is defined as the ability to conceive a child, and that’s not something we have looked at yet. We would like to know the long-term outcomes of fertility in these patients, and whether they can conceive when they’re ready to start a family. Our goal is to follow these young women into their 20s and 30s, and to see if that’s an opportunity they are able to experience.”

The study is a cooperative project involving the hospital’s divisions of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immunology, and Endocrinology.

Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.

Fertility preservation talks: The earlier, the better

A talk about fertility preservation can be the first step into a new future for families of children with a cancer diagnosis.

“Talking about your baby having a baby can be the farthest thing from your mind,” when you’re the parent of a child about to undergo cancer treatment, said Dr. Hoefgen. “But we know from survivors that this can be a very important issue in the future. We simply start by telling parents, ‘This will be important to your child at some point, and we want to talk about it now, while there is still something we may be able to do about it.’ ”

Dr. Hoefgen, a staff member at the hospital’s Comprehensive Fertility Care and Preservation Program, said parents “sometimes find it weird” to be talking about unborn grandchildren when they’re consumed with making critical decisions for their own child. But by asking them to consider that child’s long-term future, the discussion offers its own message of hope.

The talks always begin with a basic discussion of how cancer treatments can affect the reproductive organs. The hospital has a series of short animated videos that are very helpful in relaying the information. Another video in that series describes the different methods of fertility preservation: mature oocyte or sperm harvesting, or, for younger patients, removing and freezing ovarian and testicular tissue. Parents and children can watch them together, get grounding in the basics, and be prepared for a productive conversation.

Talks always include the team oncologist, who creates a specialized risk assessment for each patient. The group discusses each preservation method, the risks and benefits, and the cost. But the talks are exploratory, too, helping both clinicians and families understand what’s most important to them, she said.

“Common things that we typically talk about are genetics, religion, and ethics – which may mean different things to different families.”

Dr. Hoefgen and her team reach out to more than 95% of families that face a pediatric cancer diagnosis. After the in-depth discussions, she said, about 20% decide to investigate some form of fertility preservation.

“The most important thing is having the conversation early, while we still have options,” she said.

Dr. Hoefgen had no financial disclosures.

AT ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low or absent in all treated girls, whether they had reduced-intensity or high-intensity conditioning.

Data source: The prospective study is following 49 females aged 1-40 years.

Disclosures: Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.