User login

According to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Service, about 80% of all outpatient prescriptions filled by the VA are sent to veterans by mail order, using the Centralized Mail Order Pharmacy (CMOP) network of highly automated pharmacies around the country.1 During fiscal year (FY) 2016, the 7 VA CMOP facilities throughout the US processed 119.7 million outpatient prescriptions. Each day, these CMOPs process nearly 470,000 prescriptions, an evidence of the efficiency provided through this mail-order service.1 The use of CMOP results in lower processing costs and increased convenience for veterans compared with filling prescriptions at pharmacies at individual VA facilities. Notably, VA CMOP has been rated “among the best” mail-order pharmacies in customer satisfaction according to the 2017 J.D. Power US Pharmacy Study.2

Background

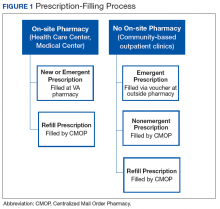

Within the Fayetteville VA Medical Center (FVAMC) system in North Carolina, on-site patients receive a new prescription where an on-site pharmacy is available (at health care centers [HCC] and the medical center). For veterans seen at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), emergent new prescriptions are filled through vouchers at contract community pharmacies, and nonemergent new prescriptions are filled by the CMOP (Figure 1).

The appropriate use of the VA CMOP for refills is intended to allow on-site pharmacy staff to focus on providing customer service for veterans requesting medication counseling from a clinical pharmacist, as well as those with new, changing, or urgent prescription needs. Filling prescriptions through the CMOP also can help control the VA facility pharmacy budget.

Despite the established mail-order process, FVAMC staff noted a high volume of medication refill and partial-fill prescriptions being requested at the on-site pharmacy. When a veteran presented to a pharmacy requesting a medication refill, pharmacy staff members ordered a refill to be filled by the CMOP and provided a limited quantity, otherwise known as a partial fill, to serve as an emergency supply to supplement the veteran until the full quantity of the prescription arrived by mail. Partial fills also were completed for new prescriptions that veterans requested to pick up at the on-site pharmacy. For new 90-day supply prescriptions, pharmacy staff often filled a 30-day supply in addition to submitting the entire 90-day prescription through the CMOP, which led to an unnecessary increase in material expenditures and workload.Preliminary data noted the most frequently used partial-fill days’ supply to be 10 days. Due to the lack of partial-fill criteria, prescriptions of all classes, quantities, and days’ supplies were provided as partial fills. Prior to the implementation of this quality improvement (QI) project, there was no standard approach for how to handle these requests.

Partial fills do not provide copay reimbursement to the facility filling the prescription. In an effort to steward the funds provided to the FVAMC pharmacy department wisely, an evaluation was performed with reference to partial fills. During FY 2016, about $350,000 was spent on medications, materials, and workload associated with the partial filling of FVAMC prescriptions. With respect to unique individuals who were provided care over the course of FY 2015 and 2016, the number of unique patients served by local comparator hospitals increased by only 2%, while the number of unique patients served by FVAMC increased by 12%. This substantial growth in the number of veterans served places further emphasis on the necessity of stewarding the allotted pharmacy budget. Moreover, the excessive number of medication refill and partial-fill prescriptions filled at on-site VA pharmacies can contribute to increased wait times for veterans with urgent prescription needs.

In November 2016, FVAMC implemented an updated partial-fill guidance. Partial-fill process and refill education was provided for VA staff and veterans in an effort to allow all parties involved to use pharmacy services efficiently. This analysis reviewed the reduction in partial-fill expenditures with a secondary focus on workload expenditures following the execution of this education.

Methods

This project was deemed to be a QI project and did not require institutional review board approval. Implementation for this QI project began in November 2016. Baseline raw drug cost, number, and class of prescriptions partialed were retrospectively collected for a 90-day period prior to implementation using all available data. Postintervention data were collected for 90 days following the implementation phase to compare partial-fill expenditures and workload expenditures with baseline data.

Calculations

Materials included in the partial-fill expenditure calculation were prescription vials, prescription vial caps, and prescription labeling. Material cost per partial fill was determined by using the facility’s wholesaler acquisition unit costs to estimate a summed cost for an individual prescription vial and prescription vial cap. The estimated acquisition price of 7 prescription-labeling pages was used in the material calculation, as this was the average number of pages used when performing test partial fills.

The following equation was used to calculate total partial-fill expenditures for any specified time frame:

Total partial-fill expenditure = total raw drug cost + (material cost × number of partial fills)

In addition, the average personnel cost per partial-fill prescription was determined. Average workload expenditure per partial fill was calculated by filling a subset of 10 test prescriptions and multiplying the average time spent by an average of the general station (GS) rate for pharmacists and technicians. The average hourly rate of a GS-12 pharmacist was calculated based on an average of the 10 available pay grades within the GS-12 ranking. The average hourly rate of a GS-6 pharmacy technician was calculated based on an average of the 10 available pay grades within the GS-6 ranking.3 The average workload expenditures were calculated using the following equations:

Average pharmacist workload expenditure per partial fill = time (in hours) × average hourly rate.

Average technician workload expenditure per partial fill = time (in hours) × average hourly rate.

Partial-Fill Guidance

Updated partial-fill guidance was drafted designating acceptable prescriptions to be limited to those responsible for preventing hospitalization and treatment of acute illness. This guidance provided generalized examples of medication classes that could be acceptable for partial filling, though it was not intended to be an all-inclusive list. The guidance also noted examples of classes or groups that should not be partial filled for nonemergent reasons (vitamins, nonprescription items, antilipemics), as well as controlled substances. The refill-process education was reiterated throughout the entirety of the guidance. Specifically, if a pharmacy staff member was to perform a partial fill, a review explaining the appropriate refill process to the veteran also must be provided. If the medication was determined to be of emergent need and not yet transmitted for filling via the CMOP, the directive recommended to fill the entire quantity locally as a onetime fill.

If a onetime on-site fill was determined infeasible, partial-fill quantities were recommended to be limited to only a 7-day supply, and the full quantity filled through the CMOP. Anticipated mail wait time for CMOP prescription delivery was estimated to be less than 7 days based on experience, local pending queues, and guidance from the regional CMOP; however, time could vary among VA and CMOP facilities. Original prescriptions were to be filled for the entire quantity for the first fill at the on-site pharmacy if requested by the veteran. If the pharmacy had an insufficient quantity for an entire initial supply, it could then be partial filled for a 7-day supply and then filled through the CMOP.

The final portion of the partial-fill guidance pertained to the use of partial-fill justification codes. Prior to the execution of the partial-fill guidance, free text was entered into the comments field when processing a partial-fill prescription, as the prescription-processing system used requires a comment to proceed with the partial fill. The use of these codes served to streamline data collection in the postintervention phase and helped identify areas for further education following the close of this project.

Education

Education to the pharmacy staff was disseminated by various modalities, including in-person sessions and written and electronic correspondences. This written guidance was distributed to pharmacy staff by e-mail, the pharmacy newsletter (Rx-tra), signage posted throughout the outpatient pharmacies, and on the facility’s pharmacy Microsoft SharePoint (Redmond, WA) site. In-services provided during pharmacy staff meetings detailed information on the updated partial-fill guidance. A FVAMC Talent Management System (TMS) training module was developed and assigned to all pharmacy service staff to reiterate key points regarding this QI initiative (eAppendix).

Nonpharmacy staff were educated through staff and in-service meetings and e-mail correspondences. These in-services emphasized how nurses, medical support assistants, and health care providers (HCPs) could assist veterans by knowing the correct refill process, ensuring sufficient refills remained until the next appointment, and providing continual refill-process education.

Following implementation, all veterans receiving prescriptions through the on-site pharmacies in the FVAMC were provided a copy of the refill-process handout with each trip to the pharmacy. Nonpharmacy staff and HCPs also were provided this handout to distribute to patients. The intent of this handout was to clearly detail the various ways in which refills could be ordered and the time frame in which they should be ordered. The pharmacy became involved in new patient orientation classes for all veterans new to FVAMC. Digital signage and messaging was created and circulated throughout several of the FVAMC facilities.

Results

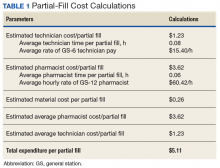

The results of calculations for material cost, personnel time spent, hourly employee rates, and average workload expenditure per partial fill are summarized in Table 1.

Following the implementation of partial-fill and refill-process education, there was a 54.3% decrease in the total number of partial fills from 5,596 in the 90 days prior to implementation, to 2,555 partials completed over the 90 days postimplementation. Regarding the primary objective, total partial-fill expenditures decreased from $52,015.44 to $44,063.01 (-15.3%). When dissecting the individual components of partial-fill expenditures, material expenditures decreased from $1,454.96 to $664.28 (-54.3%), and raw drug cost expenditures decreased from $50,596.48 to $43,398.73 (-14.3%). Workload expenditures also decreased from $27,140.60 to $12,391.75 (-54.3%).

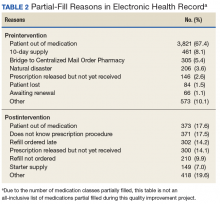

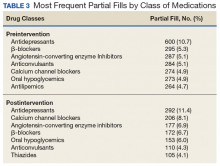

Several points of descriptive information also were collected. The average days’ supply trended down from a mode of 10 days to 7 days. This reduction in days’ supply likely was seen because staff became more aware of the customary amount required to bridge the veteran until the CMOP supply arrived by mail. Postintervention data showed a 70% utilization of partial-fill reasoning codes. The reasons for partial filling of prescriptions are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

Following the implementation of the updated partial-fill guidance and provision of education to the FVAMC veterans and staff, a noteworthy cost savings was observed with respect to both material and workload expenditures. This large reduction in expenditure likely was not related to a reduction in the total prescription volume, as the number of total prescriptions filled by the CMOP and at FVAMC were similar in both the preliminary and postintervention periods. When the results of this 3-month QI project were extrapolated, the annual projected cost avoidance was $91,949.12.

Of note, there was no established process for adjudicating appeals to the partial-fill guidance. Any extenuating circumstances that fell outside the guidance were addressed by the outpatient pharmacy supervisor. There was no formal documentation for these disputed cases. Since there was no prespecified supervisory override code, the most appropriate partial-fill code was entered into the comments field for these scenarios. As such, there is no way to distinguish precisely how many of these partial fills were escalated to a supervisory level for a decision.

The positive fiscal impact noted from the implementation of this project should not be viewed as the only utility for such guidance. Though not directly measured within the confines of this project, a reduction in pharmacy staff time spent on partial-fill prescriptions will likely result in shorter pharmacy wait times, line lengths, and streamlining of pharmacy workflow. When the pharmacy staff is free to work on pressing issues rather than on continually educating veterans on the partial-fill or refill process, many will benefit. Veteran satisfaction was not directly measured during this project but could be an interesting topic to review as a future study.

Each VA facility is unique, with its own challenges for implementation of a project such as this. Nevertheless, the incorporation of a formal guidance and education process, perhaps adapted to the indi vidual facility’s needs may be considered for overall pharmacy operations QI.

Limitations

During the preliminary data collection period, FVAMC and its catchment area were impacted by a natural disaster, Hurricane Matthew. Based on a review of the text entered into the comments field for all partial fills, about 4% of the partial fills completed in the preliminary phase can be attributed to the hurricane. The effects of this hurricane may have potentially increased the number of partial fills completed in the preliminary phase compared with that in the postintervention phase, due to the number of veterans who were temporarily or permanently displaced from their homes. This increase in partial fills and associated expenses preintervention likely caused a slightly higher cost savings to be reflected in the postimplementation phase than what would have traditionally been observed without extenuating factors.

Several other limitations must be considered for this QI project. The implementation phase, during which all education and training was completed, was only 1 month. A longer implementation period and more opportunities to educate veterans and staff might have created a greater impact on the results. Additionally, because there were no data collected on New Patient Orientation attendance for this project, it is unclear exactly how many veterans received refill-process education through this outlet.

Though all staff members were trained on the appropriate process, it was discovered during interim analysis that several pharmacists were not following the partial-fill guidance, potentially negatively impacting the results. It is likely that staff would have benefited from continual reeducation of the process throughout the entirety of the project, as the restriction of partial filling was a novel concept to many. In addition to continual reeducation of current employees, any new hires would likely need this information as part of initial training.

Cost variance in the type of partial fills completed between the preliminary and postintervention phases also may have negatively impacted the results. The postintervention phase contained 2 high-cost classes of drugs (antivirals and immunoglobulins) that received multiple partial fills but were not partialed in the preliminary phase, which increased the raw drug cost in the postintervention phase.

Conclusion

The implementation of partial-fill and process education to FVAMC staff and veterans proved beneficial in reducing the expenditures and workload associated with partial-fill prescription processing. The continued use of the updated partial-fill guidance will provide a standardized approach for pharmacy staff when completing partial-fill prescriptions.

Facilities may consider annual reeducation on their guidance through a local TMS module, as well as occasional process reminders during staff meetings to improve staff adherence to the guidance. Moreover, the sustained incorporation of improved refill process education to new patients and with every prescription pickup could help guide the FVAMC veteran population to use pharmacy services more effectively. The adoption of such procedures may be useful for VA facilities’ health care system looking to maximize the use of funding provided for prescription services as well as improve veterans’ understanding of how to appropriately order prescription refills.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy benefits management services. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/CMOP/VA_Mail_Order_Pharmacy.asp. Updated July 14, 2017. Accessed on February 26, 2018.

2. J.D. Power. Decline in pharmacy customer satisfaction driven by prescription drug costs, J. D. Power finds. [press release]. http://www.jdpower.com/press-releases/jd-power-2017-us-pharmacy-study. Published September 5, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

3. US Office of Personnel Management. Pay and leave. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/salaries-wages/. Accessed February 26, 2018.

4. Aragon BR, Pierce RA, Jones WN. VA CMOPs: producing a pattern of quality and efficiency in government. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(6):810-815.

According to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Service, about 80% of all outpatient prescriptions filled by the VA are sent to veterans by mail order, using the Centralized Mail Order Pharmacy (CMOP) network of highly automated pharmacies around the country.1 During fiscal year (FY) 2016, the 7 VA CMOP facilities throughout the US processed 119.7 million outpatient prescriptions. Each day, these CMOPs process nearly 470,000 prescriptions, an evidence of the efficiency provided through this mail-order service.1 The use of CMOP results in lower processing costs and increased convenience for veterans compared with filling prescriptions at pharmacies at individual VA facilities. Notably, VA CMOP has been rated “among the best” mail-order pharmacies in customer satisfaction according to the 2017 J.D. Power US Pharmacy Study.2

Background

Within the Fayetteville VA Medical Center (FVAMC) system in North Carolina, on-site patients receive a new prescription where an on-site pharmacy is available (at health care centers [HCC] and the medical center). For veterans seen at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), emergent new prescriptions are filled through vouchers at contract community pharmacies, and nonemergent new prescriptions are filled by the CMOP (Figure 1).

The appropriate use of the VA CMOP for refills is intended to allow on-site pharmacy staff to focus on providing customer service for veterans requesting medication counseling from a clinical pharmacist, as well as those with new, changing, or urgent prescription needs. Filling prescriptions through the CMOP also can help control the VA facility pharmacy budget.

Despite the established mail-order process, FVAMC staff noted a high volume of medication refill and partial-fill prescriptions being requested at the on-site pharmacy. When a veteran presented to a pharmacy requesting a medication refill, pharmacy staff members ordered a refill to be filled by the CMOP and provided a limited quantity, otherwise known as a partial fill, to serve as an emergency supply to supplement the veteran until the full quantity of the prescription arrived by mail. Partial fills also were completed for new prescriptions that veterans requested to pick up at the on-site pharmacy. For new 90-day supply prescriptions, pharmacy staff often filled a 30-day supply in addition to submitting the entire 90-day prescription through the CMOP, which led to an unnecessary increase in material expenditures and workload.Preliminary data noted the most frequently used partial-fill days’ supply to be 10 days. Due to the lack of partial-fill criteria, prescriptions of all classes, quantities, and days’ supplies were provided as partial fills. Prior to the implementation of this quality improvement (QI) project, there was no standard approach for how to handle these requests.

Partial fills do not provide copay reimbursement to the facility filling the prescription. In an effort to steward the funds provided to the FVAMC pharmacy department wisely, an evaluation was performed with reference to partial fills. During FY 2016, about $350,000 was spent on medications, materials, and workload associated with the partial filling of FVAMC prescriptions. With respect to unique individuals who were provided care over the course of FY 2015 and 2016, the number of unique patients served by local comparator hospitals increased by only 2%, while the number of unique patients served by FVAMC increased by 12%. This substantial growth in the number of veterans served places further emphasis on the necessity of stewarding the allotted pharmacy budget. Moreover, the excessive number of medication refill and partial-fill prescriptions filled at on-site VA pharmacies can contribute to increased wait times for veterans with urgent prescription needs.

In November 2016, FVAMC implemented an updated partial-fill guidance. Partial-fill process and refill education was provided for VA staff and veterans in an effort to allow all parties involved to use pharmacy services efficiently. This analysis reviewed the reduction in partial-fill expenditures with a secondary focus on workload expenditures following the execution of this education.

Methods

This project was deemed to be a QI project and did not require institutional review board approval. Implementation for this QI project began in November 2016. Baseline raw drug cost, number, and class of prescriptions partialed were retrospectively collected for a 90-day period prior to implementation using all available data. Postintervention data were collected for 90 days following the implementation phase to compare partial-fill expenditures and workload expenditures with baseline data.

Calculations

Materials included in the partial-fill expenditure calculation were prescription vials, prescription vial caps, and prescription labeling. Material cost per partial fill was determined by using the facility’s wholesaler acquisition unit costs to estimate a summed cost for an individual prescription vial and prescription vial cap. The estimated acquisition price of 7 prescription-labeling pages was used in the material calculation, as this was the average number of pages used when performing test partial fills.

The following equation was used to calculate total partial-fill expenditures for any specified time frame:

Total partial-fill expenditure = total raw drug cost + (material cost × number of partial fills)

In addition, the average personnel cost per partial-fill prescription was determined. Average workload expenditure per partial fill was calculated by filling a subset of 10 test prescriptions and multiplying the average time spent by an average of the general station (GS) rate for pharmacists and technicians. The average hourly rate of a GS-12 pharmacist was calculated based on an average of the 10 available pay grades within the GS-12 ranking. The average hourly rate of a GS-6 pharmacy technician was calculated based on an average of the 10 available pay grades within the GS-6 ranking.3 The average workload expenditures were calculated using the following equations:

Average pharmacist workload expenditure per partial fill = time (in hours) × average hourly rate.

Average technician workload expenditure per partial fill = time (in hours) × average hourly rate.

Partial-Fill Guidance

Updated partial-fill guidance was drafted designating acceptable prescriptions to be limited to those responsible for preventing hospitalization and treatment of acute illness. This guidance provided generalized examples of medication classes that could be acceptable for partial filling, though it was not intended to be an all-inclusive list. The guidance also noted examples of classes or groups that should not be partial filled for nonemergent reasons (vitamins, nonprescription items, antilipemics), as well as controlled substances. The refill-process education was reiterated throughout the entirety of the guidance. Specifically, if a pharmacy staff member was to perform a partial fill, a review explaining the appropriate refill process to the veteran also must be provided. If the medication was determined to be of emergent need and not yet transmitted for filling via the CMOP, the directive recommended to fill the entire quantity locally as a onetime fill.

If a onetime on-site fill was determined infeasible, partial-fill quantities were recommended to be limited to only a 7-day supply, and the full quantity filled through the CMOP. Anticipated mail wait time for CMOP prescription delivery was estimated to be less than 7 days based on experience, local pending queues, and guidance from the regional CMOP; however, time could vary among VA and CMOP facilities. Original prescriptions were to be filled for the entire quantity for the first fill at the on-site pharmacy if requested by the veteran. If the pharmacy had an insufficient quantity for an entire initial supply, it could then be partial filled for a 7-day supply and then filled through the CMOP.

The final portion of the partial-fill guidance pertained to the use of partial-fill justification codes. Prior to the execution of the partial-fill guidance, free text was entered into the comments field when processing a partial-fill prescription, as the prescription-processing system used requires a comment to proceed with the partial fill. The use of these codes served to streamline data collection in the postintervention phase and helped identify areas for further education following the close of this project.

Education

Education to the pharmacy staff was disseminated by various modalities, including in-person sessions and written and electronic correspondences. This written guidance was distributed to pharmacy staff by e-mail, the pharmacy newsletter (Rx-tra), signage posted throughout the outpatient pharmacies, and on the facility’s pharmacy Microsoft SharePoint (Redmond, WA) site. In-services provided during pharmacy staff meetings detailed information on the updated partial-fill guidance. A FVAMC Talent Management System (TMS) training module was developed and assigned to all pharmacy service staff to reiterate key points regarding this QI initiative (eAppendix).

Nonpharmacy staff were educated through staff and in-service meetings and e-mail correspondences. These in-services emphasized how nurses, medical support assistants, and health care providers (HCPs) could assist veterans by knowing the correct refill process, ensuring sufficient refills remained until the next appointment, and providing continual refill-process education.

Following implementation, all veterans receiving prescriptions through the on-site pharmacies in the FVAMC were provided a copy of the refill-process handout with each trip to the pharmacy. Nonpharmacy staff and HCPs also were provided this handout to distribute to patients. The intent of this handout was to clearly detail the various ways in which refills could be ordered and the time frame in which they should be ordered. The pharmacy became involved in new patient orientation classes for all veterans new to FVAMC. Digital signage and messaging was created and circulated throughout several of the FVAMC facilities.

Results

The results of calculations for material cost, personnel time spent, hourly employee rates, and average workload expenditure per partial fill are summarized in Table 1.

Following the implementation of partial-fill and refill-process education, there was a 54.3% decrease in the total number of partial fills from 5,596 in the 90 days prior to implementation, to 2,555 partials completed over the 90 days postimplementation. Regarding the primary objective, total partial-fill expenditures decreased from $52,015.44 to $44,063.01 (-15.3%). When dissecting the individual components of partial-fill expenditures, material expenditures decreased from $1,454.96 to $664.28 (-54.3%), and raw drug cost expenditures decreased from $50,596.48 to $43,398.73 (-14.3%). Workload expenditures also decreased from $27,140.60 to $12,391.75 (-54.3%).

Several points of descriptive information also were collected. The average days’ supply trended down from a mode of 10 days to 7 days. This reduction in days’ supply likely was seen because staff became more aware of the customary amount required to bridge the veteran until the CMOP supply arrived by mail. Postintervention data showed a 70% utilization of partial-fill reasoning codes. The reasons for partial filling of prescriptions are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

Following the implementation of the updated partial-fill guidance and provision of education to the FVAMC veterans and staff, a noteworthy cost savings was observed with respect to both material and workload expenditures. This large reduction in expenditure likely was not related to a reduction in the total prescription volume, as the number of total prescriptions filled by the CMOP and at FVAMC were similar in both the preliminary and postintervention periods. When the results of this 3-month QI project were extrapolated, the annual projected cost avoidance was $91,949.12.

Of note, there was no established process for adjudicating appeals to the partial-fill guidance. Any extenuating circumstances that fell outside the guidance were addressed by the outpatient pharmacy supervisor. There was no formal documentation for these disputed cases. Since there was no prespecified supervisory override code, the most appropriate partial-fill code was entered into the comments field for these scenarios. As such, there is no way to distinguish precisely how many of these partial fills were escalated to a supervisory level for a decision.

The positive fiscal impact noted from the implementation of this project should not be viewed as the only utility for such guidance. Though not directly measured within the confines of this project, a reduction in pharmacy staff time spent on partial-fill prescriptions will likely result in shorter pharmacy wait times, line lengths, and streamlining of pharmacy workflow. When the pharmacy staff is free to work on pressing issues rather than on continually educating veterans on the partial-fill or refill process, many will benefit. Veteran satisfaction was not directly measured during this project but could be an interesting topic to review as a future study.

Each VA facility is unique, with its own challenges for implementation of a project such as this. Nevertheless, the incorporation of a formal guidance and education process, perhaps adapted to the indi vidual facility’s needs may be considered for overall pharmacy operations QI.

Limitations

During the preliminary data collection period, FVAMC and its catchment area were impacted by a natural disaster, Hurricane Matthew. Based on a review of the text entered into the comments field for all partial fills, about 4% of the partial fills completed in the preliminary phase can be attributed to the hurricane. The effects of this hurricane may have potentially increased the number of partial fills completed in the preliminary phase compared with that in the postintervention phase, due to the number of veterans who were temporarily or permanently displaced from their homes. This increase in partial fills and associated expenses preintervention likely caused a slightly higher cost savings to be reflected in the postimplementation phase than what would have traditionally been observed without extenuating factors.

Several other limitations must be considered for this QI project. The implementation phase, during which all education and training was completed, was only 1 month. A longer implementation period and more opportunities to educate veterans and staff might have created a greater impact on the results. Additionally, because there were no data collected on New Patient Orientation attendance for this project, it is unclear exactly how many veterans received refill-process education through this outlet.

Though all staff members were trained on the appropriate process, it was discovered during interim analysis that several pharmacists were not following the partial-fill guidance, potentially negatively impacting the results. It is likely that staff would have benefited from continual reeducation of the process throughout the entirety of the project, as the restriction of partial filling was a novel concept to many. In addition to continual reeducation of current employees, any new hires would likely need this information as part of initial training.

Cost variance in the type of partial fills completed between the preliminary and postintervention phases also may have negatively impacted the results. The postintervention phase contained 2 high-cost classes of drugs (antivirals and immunoglobulins) that received multiple partial fills but were not partialed in the preliminary phase, which increased the raw drug cost in the postintervention phase.

Conclusion

The implementation of partial-fill and process education to FVAMC staff and veterans proved beneficial in reducing the expenditures and workload associated with partial-fill prescription processing. The continued use of the updated partial-fill guidance will provide a standardized approach for pharmacy staff when completing partial-fill prescriptions.

Facilities may consider annual reeducation on their guidance through a local TMS module, as well as occasional process reminders during staff meetings to improve staff adherence to the guidance. Moreover, the sustained incorporation of improved refill process education to new patients and with every prescription pickup could help guide the FVAMC veteran population to use pharmacy services more effectively. The adoption of such procedures may be useful for VA facilities’ health care system looking to maximize the use of funding provided for prescription services as well as improve veterans’ understanding of how to appropriately order prescription refills.

According to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Service, about 80% of all outpatient prescriptions filled by the VA are sent to veterans by mail order, using the Centralized Mail Order Pharmacy (CMOP) network of highly automated pharmacies around the country.1 During fiscal year (FY) 2016, the 7 VA CMOP facilities throughout the US processed 119.7 million outpatient prescriptions. Each day, these CMOPs process nearly 470,000 prescriptions, an evidence of the efficiency provided through this mail-order service.1 The use of CMOP results in lower processing costs and increased convenience for veterans compared with filling prescriptions at pharmacies at individual VA facilities. Notably, VA CMOP has been rated “among the best” mail-order pharmacies in customer satisfaction according to the 2017 J.D. Power US Pharmacy Study.2

Background

Within the Fayetteville VA Medical Center (FVAMC) system in North Carolina, on-site patients receive a new prescription where an on-site pharmacy is available (at health care centers [HCC] and the medical center). For veterans seen at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), emergent new prescriptions are filled through vouchers at contract community pharmacies, and nonemergent new prescriptions are filled by the CMOP (Figure 1).

The appropriate use of the VA CMOP for refills is intended to allow on-site pharmacy staff to focus on providing customer service for veterans requesting medication counseling from a clinical pharmacist, as well as those with new, changing, or urgent prescription needs. Filling prescriptions through the CMOP also can help control the VA facility pharmacy budget.

Despite the established mail-order process, FVAMC staff noted a high volume of medication refill and partial-fill prescriptions being requested at the on-site pharmacy. When a veteran presented to a pharmacy requesting a medication refill, pharmacy staff members ordered a refill to be filled by the CMOP and provided a limited quantity, otherwise known as a partial fill, to serve as an emergency supply to supplement the veteran until the full quantity of the prescription arrived by mail. Partial fills also were completed for new prescriptions that veterans requested to pick up at the on-site pharmacy. For new 90-day supply prescriptions, pharmacy staff often filled a 30-day supply in addition to submitting the entire 90-day prescription through the CMOP, which led to an unnecessary increase in material expenditures and workload.Preliminary data noted the most frequently used partial-fill days’ supply to be 10 days. Due to the lack of partial-fill criteria, prescriptions of all classes, quantities, and days’ supplies were provided as partial fills. Prior to the implementation of this quality improvement (QI) project, there was no standard approach for how to handle these requests.

Partial fills do not provide copay reimbursement to the facility filling the prescription. In an effort to steward the funds provided to the FVAMC pharmacy department wisely, an evaluation was performed with reference to partial fills. During FY 2016, about $350,000 was spent on medications, materials, and workload associated with the partial filling of FVAMC prescriptions. With respect to unique individuals who were provided care over the course of FY 2015 and 2016, the number of unique patients served by local comparator hospitals increased by only 2%, while the number of unique patients served by FVAMC increased by 12%. This substantial growth in the number of veterans served places further emphasis on the necessity of stewarding the allotted pharmacy budget. Moreover, the excessive number of medication refill and partial-fill prescriptions filled at on-site VA pharmacies can contribute to increased wait times for veterans with urgent prescription needs.

In November 2016, FVAMC implemented an updated partial-fill guidance. Partial-fill process and refill education was provided for VA staff and veterans in an effort to allow all parties involved to use pharmacy services efficiently. This analysis reviewed the reduction in partial-fill expenditures with a secondary focus on workload expenditures following the execution of this education.

Methods

This project was deemed to be a QI project and did not require institutional review board approval. Implementation for this QI project began in November 2016. Baseline raw drug cost, number, and class of prescriptions partialed were retrospectively collected for a 90-day period prior to implementation using all available data. Postintervention data were collected for 90 days following the implementation phase to compare partial-fill expenditures and workload expenditures with baseline data.

Calculations

Materials included in the partial-fill expenditure calculation were prescription vials, prescription vial caps, and prescription labeling. Material cost per partial fill was determined by using the facility’s wholesaler acquisition unit costs to estimate a summed cost for an individual prescription vial and prescription vial cap. The estimated acquisition price of 7 prescription-labeling pages was used in the material calculation, as this was the average number of pages used when performing test partial fills.

The following equation was used to calculate total partial-fill expenditures for any specified time frame:

Total partial-fill expenditure = total raw drug cost + (material cost × number of partial fills)

In addition, the average personnel cost per partial-fill prescription was determined. Average workload expenditure per partial fill was calculated by filling a subset of 10 test prescriptions and multiplying the average time spent by an average of the general station (GS) rate for pharmacists and technicians. The average hourly rate of a GS-12 pharmacist was calculated based on an average of the 10 available pay grades within the GS-12 ranking. The average hourly rate of a GS-6 pharmacy technician was calculated based on an average of the 10 available pay grades within the GS-6 ranking.3 The average workload expenditures were calculated using the following equations:

Average pharmacist workload expenditure per partial fill = time (in hours) × average hourly rate.

Average technician workload expenditure per partial fill = time (in hours) × average hourly rate.

Partial-Fill Guidance

Updated partial-fill guidance was drafted designating acceptable prescriptions to be limited to those responsible for preventing hospitalization and treatment of acute illness. This guidance provided generalized examples of medication classes that could be acceptable for partial filling, though it was not intended to be an all-inclusive list. The guidance also noted examples of classes or groups that should not be partial filled for nonemergent reasons (vitamins, nonprescription items, antilipemics), as well as controlled substances. The refill-process education was reiterated throughout the entirety of the guidance. Specifically, if a pharmacy staff member was to perform a partial fill, a review explaining the appropriate refill process to the veteran also must be provided. If the medication was determined to be of emergent need and not yet transmitted for filling via the CMOP, the directive recommended to fill the entire quantity locally as a onetime fill.

If a onetime on-site fill was determined infeasible, partial-fill quantities were recommended to be limited to only a 7-day supply, and the full quantity filled through the CMOP. Anticipated mail wait time for CMOP prescription delivery was estimated to be less than 7 days based on experience, local pending queues, and guidance from the regional CMOP; however, time could vary among VA and CMOP facilities. Original prescriptions were to be filled for the entire quantity for the first fill at the on-site pharmacy if requested by the veteran. If the pharmacy had an insufficient quantity for an entire initial supply, it could then be partial filled for a 7-day supply and then filled through the CMOP.

The final portion of the partial-fill guidance pertained to the use of partial-fill justification codes. Prior to the execution of the partial-fill guidance, free text was entered into the comments field when processing a partial-fill prescription, as the prescription-processing system used requires a comment to proceed with the partial fill. The use of these codes served to streamline data collection in the postintervention phase and helped identify areas for further education following the close of this project.

Education

Education to the pharmacy staff was disseminated by various modalities, including in-person sessions and written and electronic correspondences. This written guidance was distributed to pharmacy staff by e-mail, the pharmacy newsletter (Rx-tra), signage posted throughout the outpatient pharmacies, and on the facility’s pharmacy Microsoft SharePoint (Redmond, WA) site. In-services provided during pharmacy staff meetings detailed information on the updated partial-fill guidance. A FVAMC Talent Management System (TMS) training module was developed and assigned to all pharmacy service staff to reiterate key points regarding this QI initiative (eAppendix).

Nonpharmacy staff were educated through staff and in-service meetings and e-mail correspondences. These in-services emphasized how nurses, medical support assistants, and health care providers (HCPs) could assist veterans by knowing the correct refill process, ensuring sufficient refills remained until the next appointment, and providing continual refill-process education.

Following implementation, all veterans receiving prescriptions through the on-site pharmacies in the FVAMC were provided a copy of the refill-process handout with each trip to the pharmacy. Nonpharmacy staff and HCPs also were provided this handout to distribute to patients. The intent of this handout was to clearly detail the various ways in which refills could be ordered and the time frame in which they should be ordered. The pharmacy became involved in new patient orientation classes for all veterans new to FVAMC. Digital signage and messaging was created and circulated throughout several of the FVAMC facilities.

Results

The results of calculations for material cost, personnel time spent, hourly employee rates, and average workload expenditure per partial fill are summarized in Table 1.

Following the implementation of partial-fill and refill-process education, there was a 54.3% decrease in the total number of partial fills from 5,596 in the 90 days prior to implementation, to 2,555 partials completed over the 90 days postimplementation. Regarding the primary objective, total partial-fill expenditures decreased from $52,015.44 to $44,063.01 (-15.3%). When dissecting the individual components of partial-fill expenditures, material expenditures decreased from $1,454.96 to $664.28 (-54.3%), and raw drug cost expenditures decreased from $50,596.48 to $43,398.73 (-14.3%). Workload expenditures also decreased from $27,140.60 to $12,391.75 (-54.3%).

Several points of descriptive information also were collected. The average days’ supply trended down from a mode of 10 days to 7 days. This reduction in days’ supply likely was seen because staff became more aware of the customary amount required to bridge the veteran until the CMOP supply arrived by mail. Postintervention data showed a 70% utilization of partial-fill reasoning codes. The reasons for partial filling of prescriptions are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

Following the implementation of the updated partial-fill guidance and provision of education to the FVAMC veterans and staff, a noteworthy cost savings was observed with respect to both material and workload expenditures. This large reduction in expenditure likely was not related to a reduction in the total prescription volume, as the number of total prescriptions filled by the CMOP and at FVAMC were similar in both the preliminary and postintervention periods. When the results of this 3-month QI project were extrapolated, the annual projected cost avoidance was $91,949.12.

Of note, there was no established process for adjudicating appeals to the partial-fill guidance. Any extenuating circumstances that fell outside the guidance were addressed by the outpatient pharmacy supervisor. There was no formal documentation for these disputed cases. Since there was no prespecified supervisory override code, the most appropriate partial-fill code was entered into the comments field for these scenarios. As such, there is no way to distinguish precisely how many of these partial fills were escalated to a supervisory level for a decision.

The positive fiscal impact noted from the implementation of this project should not be viewed as the only utility for such guidance. Though not directly measured within the confines of this project, a reduction in pharmacy staff time spent on partial-fill prescriptions will likely result in shorter pharmacy wait times, line lengths, and streamlining of pharmacy workflow. When the pharmacy staff is free to work on pressing issues rather than on continually educating veterans on the partial-fill or refill process, many will benefit. Veteran satisfaction was not directly measured during this project but could be an interesting topic to review as a future study.

Each VA facility is unique, with its own challenges for implementation of a project such as this. Nevertheless, the incorporation of a formal guidance and education process, perhaps adapted to the indi vidual facility’s needs may be considered for overall pharmacy operations QI.

Limitations

During the preliminary data collection period, FVAMC and its catchment area were impacted by a natural disaster, Hurricane Matthew. Based on a review of the text entered into the comments field for all partial fills, about 4% of the partial fills completed in the preliminary phase can be attributed to the hurricane. The effects of this hurricane may have potentially increased the number of partial fills completed in the preliminary phase compared with that in the postintervention phase, due to the number of veterans who were temporarily or permanently displaced from their homes. This increase in partial fills and associated expenses preintervention likely caused a slightly higher cost savings to be reflected in the postimplementation phase than what would have traditionally been observed without extenuating factors.

Several other limitations must be considered for this QI project. The implementation phase, during which all education and training was completed, was only 1 month. A longer implementation period and more opportunities to educate veterans and staff might have created a greater impact on the results. Additionally, because there were no data collected on New Patient Orientation attendance for this project, it is unclear exactly how many veterans received refill-process education through this outlet.

Though all staff members were trained on the appropriate process, it was discovered during interim analysis that several pharmacists were not following the partial-fill guidance, potentially negatively impacting the results. It is likely that staff would have benefited from continual reeducation of the process throughout the entirety of the project, as the restriction of partial filling was a novel concept to many. In addition to continual reeducation of current employees, any new hires would likely need this information as part of initial training.

Cost variance in the type of partial fills completed between the preliminary and postintervention phases also may have negatively impacted the results. The postintervention phase contained 2 high-cost classes of drugs (antivirals and immunoglobulins) that received multiple partial fills but were not partialed in the preliminary phase, which increased the raw drug cost in the postintervention phase.

Conclusion

The implementation of partial-fill and process education to FVAMC staff and veterans proved beneficial in reducing the expenditures and workload associated with partial-fill prescription processing. The continued use of the updated partial-fill guidance will provide a standardized approach for pharmacy staff when completing partial-fill prescriptions.

Facilities may consider annual reeducation on their guidance through a local TMS module, as well as occasional process reminders during staff meetings to improve staff adherence to the guidance. Moreover, the sustained incorporation of improved refill process education to new patients and with every prescription pickup could help guide the FVAMC veteran population to use pharmacy services more effectively. The adoption of such procedures may be useful for VA facilities’ health care system looking to maximize the use of funding provided for prescription services as well as improve veterans’ understanding of how to appropriately order prescription refills.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy benefits management services. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/CMOP/VA_Mail_Order_Pharmacy.asp. Updated July 14, 2017. Accessed on February 26, 2018.

2. J.D. Power. Decline in pharmacy customer satisfaction driven by prescription drug costs, J. D. Power finds. [press release]. http://www.jdpower.com/press-releases/jd-power-2017-us-pharmacy-study. Published September 5, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

3. US Office of Personnel Management. Pay and leave. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/salaries-wages/. Accessed February 26, 2018.

4. Aragon BR, Pierce RA, Jones WN. VA CMOPs: producing a pattern of quality and efficiency in government. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(6):810-815.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy benefits management services. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/CMOP/VA_Mail_Order_Pharmacy.asp. Updated July 14, 2017. Accessed on February 26, 2018.

2. J.D. Power. Decline in pharmacy customer satisfaction driven by prescription drug costs, J. D. Power finds. [press release]. http://www.jdpower.com/press-releases/jd-power-2017-us-pharmacy-study. Published September 5, 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

3. US Office of Personnel Management. Pay and leave. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/salaries-wages/. Accessed February 26, 2018.

4. Aragon BR, Pierce RA, Jones WN. VA CMOPs: producing a pattern of quality and efficiency in government. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(6):810-815.