User login

Patients with chronic illness, such as diabetes, are expected, and taught how, to participate in managing their disease. On the other hand, patients with serious mental illness historically have been thought of as passive recipients of care. Attitudes of care providers, patients, and family members are changing, however, and, in the last decade, the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) program has been developed for treating patients with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, using principles of chronic disease management.1 Consider using this evidence-based psychosocial treatment modality for your patients with schizophrenia.

Basic philosophy

A core assumption of IMR is realistic optimism that recovery is possible. Recovery, in this context, means that a patient can have a meaningful life despite having a serious illness. In IMR, patients engage in developing and tracking their progress toward personally meaningful goals; that progress is broken down into small steps and worked on over the course of the program.

Critical components

IMR addresses practical matters of living with schizophrenia, including coping with symptoms and collaborating with providers. The program combines elements from 6 areas:

• psychoeducation

• cognitive-behavioral approaches to medication management and other treatment targets

• motivational interviewing

• relapse prevention planning

• social skills training

• coping skills to manage persistent symptoms.

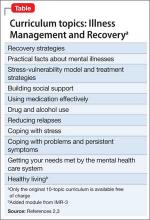

The original curriculum, which is available free of charge, comprises 10 topics (Table).2 Of note, the newest version, IMR-3, includes an additional module focused on healthy lifestyles.3

Implementation

Although typically delivered as a structured weekly group intervention for 9 to 12 months, IMR can be taught individually. Involving a supportive person such as a family member, case manager, or residential staff member can be useful. Physicians can select modules tailored to the patient’s needs. Any physician who wants to bring IMR to her (his) patient can download the SAMHSA Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices KIT (Knowledge Informing Transformation).2 This free download provides the full curriculum with handouts, and tips and training tools related to implementation and evaluation of IMR in a typical mental health care setting.

IMR is well-accepted by most participants; studies report a median 63% of patients complete IMR.4 Attendance for the intervention appears to be better in a group, rather than an individual, format. A number of patient characteristics, including older age, lower hostility, fewer psychotic symptoms, and more education, have been identified as predictors of better attendance to manualized psychosocial treatments, such as IMR.5

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(suppl 1):S32-S43.

2. SAMSHA. Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) KIT. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Illness-Management-and-Recovery-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA09-4463. Published March 2010. Accessed October 16, 2014.

3. Mueser KT, Gingerich S. Illness Management and Recovery. 3rd ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2011.

4. McGuire AB, Kukla M, Green A, et al. Illness management and recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):171-179.

5. McGuire AB, Bonfils KA, Kukla M, et al. Measuring participation in an evidence-based practice: illness management and recovery group attendance. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):684-689.

Patients with chronic illness, such as diabetes, are expected, and taught how, to participate in managing their disease. On the other hand, patients with serious mental illness historically have been thought of as passive recipients of care. Attitudes of care providers, patients, and family members are changing, however, and, in the last decade, the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) program has been developed for treating patients with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, using principles of chronic disease management.1 Consider using this evidence-based psychosocial treatment modality for your patients with schizophrenia.

Basic philosophy

A core assumption of IMR is realistic optimism that recovery is possible. Recovery, in this context, means that a patient can have a meaningful life despite having a serious illness. In IMR, patients engage in developing and tracking their progress toward personally meaningful goals; that progress is broken down into small steps and worked on over the course of the program.

Critical components

IMR addresses practical matters of living with schizophrenia, including coping with symptoms and collaborating with providers. The program combines elements from 6 areas:

• psychoeducation

• cognitive-behavioral approaches to medication management and other treatment targets

• motivational interviewing

• relapse prevention planning

• social skills training

• coping skills to manage persistent symptoms.

The original curriculum, which is available free of charge, comprises 10 topics (Table).2 Of note, the newest version, IMR-3, includes an additional module focused on healthy lifestyles.3

Implementation

Although typically delivered as a structured weekly group intervention for 9 to 12 months, IMR can be taught individually. Involving a supportive person such as a family member, case manager, or residential staff member can be useful. Physicians can select modules tailored to the patient’s needs. Any physician who wants to bring IMR to her (his) patient can download the SAMHSA Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices KIT (Knowledge Informing Transformation).2 This free download provides the full curriculum with handouts, and tips and training tools related to implementation and evaluation of IMR in a typical mental health care setting.

IMR is well-accepted by most participants; studies report a median 63% of patients complete IMR.4 Attendance for the intervention appears to be better in a group, rather than an individual, format. A number of patient characteristics, including older age, lower hostility, fewer psychotic symptoms, and more education, have been identified as predictors of better attendance to manualized psychosocial treatments, such as IMR.5

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Patients with chronic illness, such as diabetes, are expected, and taught how, to participate in managing their disease. On the other hand, patients with serious mental illness historically have been thought of as passive recipients of care. Attitudes of care providers, patients, and family members are changing, however, and, in the last decade, the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) program has been developed for treating patients with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, using principles of chronic disease management.1 Consider using this evidence-based psychosocial treatment modality for your patients with schizophrenia.

Basic philosophy

A core assumption of IMR is realistic optimism that recovery is possible. Recovery, in this context, means that a patient can have a meaningful life despite having a serious illness. In IMR, patients engage in developing and tracking their progress toward personally meaningful goals; that progress is broken down into small steps and worked on over the course of the program.

Critical components

IMR addresses practical matters of living with schizophrenia, including coping with symptoms and collaborating with providers. The program combines elements from 6 areas:

• psychoeducation

• cognitive-behavioral approaches to medication management and other treatment targets

• motivational interviewing

• relapse prevention planning

• social skills training

• coping skills to manage persistent symptoms.

The original curriculum, which is available free of charge, comprises 10 topics (Table).2 Of note, the newest version, IMR-3, includes an additional module focused on healthy lifestyles.3

Implementation

Although typically delivered as a structured weekly group intervention for 9 to 12 months, IMR can be taught individually. Involving a supportive person such as a family member, case manager, or residential staff member can be useful. Physicians can select modules tailored to the patient’s needs. Any physician who wants to bring IMR to her (his) patient can download the SAMHSA Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices KIT (Knowledge Informing Transformation).2 This free download provides the full curriculum with handouts, and tips and training tools related to implementation and evaluation of IMR in a typical mental health care setting.

IMR is well-accepted by most participants; studies report a median 63% of patients complete IMR.4 Attendance for the intervention appears to be better in a group, rather than an individual, format. A number of patient characteristics, including older age, lower hostility, fewer psychotic symptoms, and more education, have been identified as predictors of better attendance to manualized psychosocial treatments, such as IMR.5

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(suppl 1):S32-S43.

2. SAMSHA. Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) KIT. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Illness-Management-and-Recovery-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA09-4463. Published March 2010. Accessed October 16, 2014.

3. Mueser KT, Gingerich S. Illness Management and Recovery. 3rd ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2011.

4. McGuire AB, Kukla M, Green A, et al. Illness management and recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):171-179.

5. McGuire AB, Bonfils KA, Kukla M, et al. Measuring participation in an evidence-based practice: illness management and recovery group attendance. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):684-689.

1. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(suppl 1):S32-S43.

2. SAMSHA. Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) KIT. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Illness-Management-and-Recovery-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA09-4463. Published March 2010. Accessed October 16, 2014.

3. Mueser KT, Gingerich S. Illness Management and Recovery. 3rd ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2011.

4. McGuire AB, Kukla M, Green A, et al. Illness management and recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):171-179.

5. McGuire AB, Bonfils KA, Kukla M, et al. Measuring participation in an evidence-based practice: illness management and recovery group attendance. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):684-689.