User login

Clozapine-induced GI hypomotility: From constipation to bowel obstruction

Patients who are treated with clozapine—a second-generation antipsychotic approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia—require monitoring for serious adverse effects. Many of these adverse effects, such as agranulocytosis or seizures, are familiar to clinicians; however, gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility is not always recognized as a potentially serious adverse effect, even though it is one of the most common causes for hospital admission.1 Its manifestations range from being relatively benign (nausea, vomiting, constipation) to potentially severe (fecal impaction) or even life-threatening (bowel obstruction, ileus, toxic megacolon).2

GI hypomotility is caused by clozapine’s strong anticholinergic properties, which lead to slowed smooth muscle contractions and delayed bowel transit time. It is further compounded by clozapine’s 5-HT3 antagonism, which is also known to slow bowel transit time. To avoid the potentially serious risks associated with GI hypomotility, we offer simple approaches for clinicians to follow when treating patients with clozapine.

Before starting a patient on clozapine, and at all subsequent visits, ask him or her about bowel habits and GI symptoms. Because the onset of GI hypomotility can be subtle, ask patients to pay close attention to their bowel habits and keep a diary to document GI symptoms and bowel movements. Signs of bowel obstruction can include an inability to pass stool, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and a bloated abdomen. Staff who care for patients taking clozapine who live in a supervised setting should be educated about the relevance of a patient’s changing bowel habits or GI complaints. Also, teach patients about simple lifestyle modifications they can make to counteract constipation, including increased physical activity, adequate hydration, and consuming a fiber-rich diet.

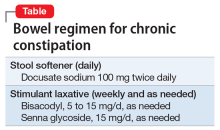

If possible, avoid prescribing anticholinergic medications to a patient receiving clozapine because such agents may add to clozapine’s anticholinergic load. Some patients may require medical management of chronic constipation with stool softeners and stimulant laxatives. The Table outlines a typical bowel regimen we use for patients at our clinic. Some clinicians may prefer earlier and more regular use of senna glycoside. Also, patients might need a referral to their primary care physician if prevention has failed and fecal impaction requires enemas or mechanical disimpaction. An urgent referral to the emergency department is needed if a patient has a suspected bowel obstruction.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Travis Baggett, MD, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, for reviewing the medical management of constipation.

1. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of clozapine and standard antipsychotic treatment in adults with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):166-173.

2. Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM. Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: a 22-year bi-national pharmacovigilance study of serious or fatal ‘slow gut’ reactions, and comparison with international drug safety advice. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(8):699-709.

Patients who are treated with clozapine—a second-generation antipsychotic approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia—require monitoring for serious adverse effects. Many of these adverse effects, such as agranulocytosis or seizures, are familiar to clinicians; however, gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility is not always recognized as a potentially serious adverse effect, even though it is one of the most common causes for hospital admission.1 Its manifestations range from being relatively benign (nausea, vomiting, constipation) to potentially severe (fecal impaction) or even life-threatening (bowel obstruction, ileus, toxic megacolon).2

GI hypomotility is caused by clozapine’s strong anticholinergic properties, which lead to slowed smooth muscle contractions and delayed bowel transit time. It is further compounded by clozapine’s 5-HT3 antagonism, which is also known to slow bowel transit time. To avoid the potentially serious risks associated with GI hypomotility, we offer simple approaches for clinicians to follow when treating patients with clozapine.

Before starting a patient on clozapine, and at all subsequent visits, ask him or her about bowel habits and GI symptoms. Because the onset of GI hypomotility can be subtle, ask patients to pay close attention to their bowel habits and keep a diary to document GI symptoms and bowel movements. Signs of bowel obstruction can include an inability to pass stool, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and a bloated abdomen. Staff who care for patients taking clozapine who live in a supervised setting should be educated about the relevance of a patient’s changing bowel habits or GI complaints. Also, teach patients about simple lifestyle modifications they can make to counteract constipation, including increased physical activity, adequate hydration, and consuming a fiber-rich diet.

If possible, avoid prescribing anticholinergic medications to a patient receiving clozapine because such agents may add to clozapine’s anticholinergic load. Some patients may require medical management of chronic constipation with stool softeners and stimulant laxatives. The Table outlines a typical bowel regimen we use for patients at our clinic. Some clinicians may prefer earlier and more regular use of senna glycoside. Also, patients might need a referral to their primary care physician if prevention has failed and fecal impaction requires enemas or mechanical disimpaction. An urgent referral to the emergency department is needed if a patient has a suspected bowel obstruction.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Travis Baggett, MD, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, for reviewing the medical management of constipation.

Patients who are treated with clozapine—a second-generation antipsychotic approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia—require monitoring for serious adverse effects. Many of these adverse effects, such as agranulocytosis or seizures, are familiar to clinicians; however, gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility is not always recognized as a potentially serious adverse effect, even though it is one of the most common causes for hospital admission.1 Its manifestations range from being relatively benign (nausea, vomiting, constipation) to potentially severe (fecal impaction) or even life-threatening (bowel obstruction, ileus, toxic megacolon).2

GI hypomotility is caused by clozapine’s strong anticholinergic properties, which lead to slowed smooth muscle contractions and delayed bowel transit time. It is further compounded by clozapine’s 5-HT3 antagonism, which is also known to slow bowel transit time. To avoid the potentially serious risks associated with GI hypomotility, we offer simple approaches for clinicians to follow when treating patients with clozapine.

Before starting a patient on clozapine, and at all subsequent visits, ask him or her about bowel habits and GI symptoms. Because the onset of GI hypomotility can be subtle, ask patients to pay close attention to their bowel habits and keep a diary to document GI symptoms and bowel movements. Signs of bowel obstruction can include an inability to pass stool, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and a bloated abdomen. Staff who care for patients taking clozapine who live in a supervised setting should be educated about the relevance of a patient’s changing bowel habits or GI complaints. Also, teach patients about simple lifestyle modifications they can make to counteract constipation, including increased physical activity, adequate hydration, and consuming a fiber-rich diet.

If possible, avoid prescribing anticholinergic medications to a patient receiving clozapine because such agents may add to clozapine’s anticholinergic load. Some patients may require medical management of chronic constipation with stool softeners and stimulant laxatives. The Table outlines a typical bowel regimen we use for patients at our clinic. Some clinicians may prefer earlier and more regular use of senna glycoside. Also, patients might need a referral to their primary care physician if prevention has failed and fecal impaction requires enemas or mechanical disimpaction. An urgent referral to the emergency department is needed if a patient has a suspected bowel obstruction.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Travis Baggett, MD, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, for reviewing the medical management of constipation.

1. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of clozapine and standard antipsychotic treatment in adults with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):166-173.

2. Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM. Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: a 22-year bi-national pharmacovigilance study of serious or fatal ‘slow gut’ reactions, and comparison with international drug safety advice. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(8):699-709.

1. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of clozapine and standard antipsychotic treatment in adults with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):166-173.

2. Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM. Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: a 22-year bi-national pharmacovigilance study of serious or fatal ‘slow gut’ reactions, and comparison with international drug safety advice. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(8):699-709.

4 Ways to help your patients with schizophrenia quit smoking

Tobacco-related cardiovascular disease is the primary reason adults with schizophrenia die on average 28 years earlier than their peers in the U.S. general population.1 To address this, clinicians need to prioritize smoking cessation and emphasize to patients with schizophrenia that quitting is the most important change they can make to improve their health. Here are 4 ways to help patients with schizophrenia quit smoking.

Provide hope, but be realistic. Most patients with schizophrenia who smoke want to quit; however, patients and clinicians alike have been discouraged by low quit rates and high relapse rates. Smoking often is viewed as one of the few remaining personal freedoms, as a lower priority than active psychiatric symptoms, or even as neuroprotective. By perpetuating these falsehoods and avoiding addressing smoking cessation, we are failing our patients.

With persistent engagement and use of effective pharmacotherapeutic interventions, smoking cessation is attainable and does not worsen psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, smoking cessation could save patients >$4,000 a year. It is crucial to make smoking cessation a priority at every appointment, and to offer patients hope and practical guidance through repeated attempts to quit.

Offer varenicline. For patients with schizophrenia, cessation counseling or behavioral interventions alone have a poor efficacy rate of approximately 5% (compared with 15% to 20% in the general population).2 Varenicline is the most effective smoking cessation treatment; it increases cessation rates 5-fold among patients with schizophrenia.3 As demonstrated by the Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES),4 varenicline does not lead to an increased risk of suicidality or serious neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

When starting a patient on varenicline, set a quit date 4 weeks from medication initiation. Individuals with schizophrenia often have a greater smoking burden and experience more intense symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. A 4-week period between medication initiation and the quit date will allow these patients to gradually experience reduced cravings and separate minor adverse effects of the medication from those of nicotine withdrawal. Concurrent prescription of nicotine replacement therapy (eg, patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler) also is safe and can assist in quit attempts.

Consider varenicline maintenance therapy. After a successful quit attempt, increase the likelihood of sustained cessation by continuing varenicline beyond 12 weeks. Varenicline can be used as a maintenance medication to prevent smoking relapse in patients with schizophrenia; when prescribed to these patients for an additional 3 months, it can reduce the relapse rate similarly to that seen in smokers in the general population.5

Adjust antipsychotic dosages. Tobacco smoke increases the activity of cytochrome P450 1A2, which metabolizes several antipsychotics. Thus, after successful smoking cessation, concentrations of clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, and olanzapine may increase, and dose reduction may be warranted. Conversely, if a patient resumes smoking, dosages of these medications may need to be increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Eden Evins, MD, MPH, and Corinne Cather, PhD, for their input on this article.

1. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

2. Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2(2):CD007253.

3. Evins AE, Benowitz N, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion vs. nicotine patch and placebo in the psychiatric cohort of the EAGLES trial. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 22nd Annual Meeting; March 2-5, 2016; Chicago, IL.

4. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

5. Evins AE, Hoeppner SS, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Maintenance pharmacotherapy normalizes the relapse curve in recently abstinent tobacco smokers with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:124-129.

Tobacco-related cardiovascular disease is the primary reason adults with schizophrenia die on average 28 years earlier than their peers in the U.S. general population.1 To address this, clinicians need to prioritize smoking cessation and emphasize to patients with schizophrenia that quitting is the most important change they can make to improve their health. Here are 4 ways to help patients with schizophrenia quit smoking.

Provide hope, but be realistic. Most patients with schizophrenia who smoke want to quit; however, patients and clinicians alike have been discouraged by low quit rates and high relapse rates. Smoking often is viewed as one of the few remaining personal freedoms, as a lower priority than active psychiatric symptoms, or even as neuroprotective. By perpetuating these falsehoods and avoiding addressing smoking cessation, we are failing our patients.

With persistent engagement and use of effective pharmacotherapeutic interventions, smoking cessation is attainable and does not worsen psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, smoking cessation could save patients >$4,000 a year. It is crucial to make smoking cessation a priority at every appointment, and to offer patients hope and practical guidance through repeated attempts to quit.

Offer varenicline. For patients with schizophrenia, cessation counseling or behavioral interventions alone have a poor efficacy rate of approximately 5% (compared with 15% to 20% in the general population).2 Varenicline is the most effective smoking cessation treatment; it increases cessation rates 5-fold among patients with schizophrenia.3 As demonstrated by the Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES),4 varenicline does not lead to an increased risk of suicidality or serious neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

When starting a patient on varenicline, set a quit date 4 weeks from medication initiation. Individuals with schizophrenia often have a greater smoking burden and experience more intense symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. A 4-week period between medication initiation and the quit date will allow these patients to gradually experience reduced cravings and separate minor adverse effects of the medication from those of nicotine withdrawal. Concurrent prescription of nicotine replacement therapy (eg, patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler) also is safe and can assist in quit attempts.

Consider varenicline maintenance therapy. After a successful quit attempt, increase the likelihood of sustained cessation by continuing varenicline beyond 12 weeks. Varenicline can be used as a maintenance medication to prevent smoking relapse in patients with schizophrenia; when prescribed to these patients for an additional 3 months, it can reduce the relapse rate similarly to that seen in smokers in the general population.5

Adjust antipsychotic dosages. Tobacco smoke increases the activity of cytochrome P450 1A2, which metabolizes several antipsychotics. Thus, after successful smoking cessation, concentrations of clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, and olanzapine may increase, and dose reduction may be warranted. Conversely, if a patient resumes smoking, dosages of these medications may need to be increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Eden Evins, MD, MPH, and Corinne Cather, PhD, for their input on this article.

Tobacco-related cardiovascular disease is the primary reason adults with schizophrenia die on average 28 years earlier than their peers in the U.S. general population.1 To address this, clinicians need to prioritize smoking cessation and emphasize to patients with schizophrenia that quitting is the most important change they can make to improve their health. Here are 4 ways to help patients with schizophrenia quit smoking.

Provide hope, but be realistic. Most patients with schizophrenia who smoke want to quit; however, patients and clinicians alike have been discouraged by low quit rates and high relapse rates. Smoking often is viewed as one of the few remaining personal freedoms, as a lower priority than active psychiatric symptoms, or even as neuroprotective. By perpetuating these falsehoods and avoiding addressing smoking cessation, we are failing our patients.

With persistent engagement and use of effective pharmacotherapeutic interventions, smoking cessation is attainable and does not worsen psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, smoking cessation could save patients >$4,000 a year. It is crucial to make smoking cessation a priority at every appointment, and to offer patients hope and practical guidance through repeated attempts to quit.

Offer varenicline. For patients with schizophrenia, cessation counseling or behavioral interventions alone have a poor efficacy rate of approximately 5% (compared with 15% to 20% in the general population).2 Varenicline is the most effective smoking cessation treatment; it increases cessation rates 5-fold among patients with schizophrenia.3 As demonstrated by the Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES),4 varenicline does not lead to an increased risk of suicidality or serious neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

When starting a patient on varenicline, set a quit date 4 weeks from medication initiation. Individuals with schizophrenia often have a greater smoking burden and experience more intense symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. A 4-week period between medication initiation and the quit date will allow these patients to gradually experience reduced cravings and separate minor adverse effects of the medication from those of nicotine withdrawal. Concurrent prescription of nicotine replacement therapy (eg, patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler) also is safe and can assist in quit attempts.

Consider varenicline maintenance therapy. After a successful quit attempt, increase the likelihood of sustained cessation by continuing varenicline beyond 12 weeks. Varenicline can be used as a maintenance medication to prevent smoking relapse in patients with schizophrenia; when prescribed to these patients for an additional 3 months, it can reduce the relapse rate similarly to that seen in smokers in the general population.5

Adjust antipsychotic dosages. Tobacco smoke increases the activity of cytochrome P450 1A2, which metabolizes several antipsychotics. Thus, after successful smoking cessation, concentrations of clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, and olanzapine may increase, and dose reduction may be warranted. Conversely, if a patient resumes smoking, dosages of these medications may need to be increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Eden Evins, MD, MPH, and Corinne Cather, PhD, for their input on this article.

1. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

2. Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2(2):CD007253.

3. Evins AE, Benowitz N, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion vs. nicotine patch and placebo in the psychiatric cohort of the EAGLES trial. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 22nd Annual Meeting; March 2-5, 2016; Chicago, IL.

4. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

5. Evins AE, Hoeppner SS, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Maintenance pharmacotherapy normalizes the relapse curve in recently abstinent tobacco smokers with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:124-129.

1. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

2. Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2(2):CD007253.

3. Evins AE, Benowitz N, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion vs. nicotine patch and placebo in the psychiatric cohort of the EAGLES trial. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 22nd Annual Meeting; March 2-5, 2016; Chicago, IL.

4. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

5. Evins AE, Hoeppner SS, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Maintenance pharmacotherapy normalizes the relapse curve in recently abstinent tobacco smokers with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:124-129.

Self-management of mental illness? It’s possible

Patients with chronic illness, such as diabetes, are expected, and taught how, to participate in managing their disease. On the other hand, patients with serious mental illness historically have been thought of as passive recipients of care. Attitudes of care providers, patients, and family members are changing, however, and, in the last decade, the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) program has been developed for treating patients with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, using principles of chronic disease management.1 Consider using this evidence-based psychosocial treatment modality for your patients with schizophrenia.

Basic philosophy

A core assumption of IMR is realistic optimism that recovery is possible. Recovery, in this context, means that a patient can have a meaningful life despite having a serious illness. In IMR, patients engage in developing and tracking their progress toward personally meaningful goals; that progress is broken down into small steps and worked on over the course of the program.

Critical components

IMR addresses practical matters of living with schizophrenia, including coping with symptoms and collaborating with providers. The program combines elements from 6 areas:

• psychoeducation

• cognitive-behavioral approaches to medication management and other treatment targets

• motivational interviewing

• relapse prevention planning

• social skills training

• coping skills to manage persistent symptoms.

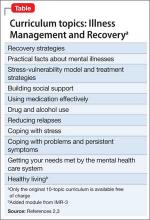

The original curriculum, which is available free of charge, comprises 10 topics (Table).2 Of note, the newest version, IMR-3, includes an additional module focused on healthy lifestyles.3

Implementation

Although typically delivered as a structured weekly group intervention for 9 to 12 months, IMR can be taught individually. Involving a supportive person such as a family member, case manager, or residential staff member can be useful. Physicians can select modules tailored to the patient’s needs. Any physician who wants to bring IMR to her (his) patient can download the SAMHSA Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices KIT (Knowledge Informing Transformation).2 This free download provides the full curriculum with handouts, and tips and training tools related to implementation and evaluation of IMR in a typical mental health care setting.

IMR is well-accepted by most participants; studies report a median 63% of patients complete IMR.4 Attendance for the intervention appears to be better in a group, rather than an individual, format. A number of patient characteristics, including older age, lower hostility, fewer psychotic symptoms, and more education, have been identified as predictors of better attendance to manualized psychosocial treatments, such as IMR.5

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(suppl 1):S32-S43.

2. SAMSHA. Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) KIT. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Illness-Management-and-Recovery-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA09-4463. Published March 2010. Accessed October 16, 2014.

3. Mueser KT, Gingerich S. Illness Management and Recovery. 3rd ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2011.

4. McGuire AB, Kukla M, Green A, et al. Illness management and recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):171-179.

5. McGuire AB, Bonfils KA, Kukla M, et al. Measuring participation in an evidence-based practice: illness management and recovery group attendance. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):684-689.

Patients with chronic illness, such as diabetes, are expected, and taught how, to participate in managing their disease. On the other hand, patients with serious mental illness historically have been thought of as passive recipients of care. Attitudes of care providers, patients, and family members are changing, however, and, in the last decade, the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) program has been developed for treating patients with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, using principles of chronic disease management.1 Consider using this evidence-based psychosocial treatment modality for your patients with schizophrenia.

Basic philosophy

A core assumption of IMR is realistic optimism that recovery is possible. Recovery, in this context, means that a patient can have a meaningful life despite having a serious illness. In IMR, patients engage in developing and tracking their progress toward personally meaningful goals; that progress is broken down into small steps and worked on over the course of the program.

Critical components

IMR addresses practical matters of living with schizophrenia, including coping with symptoms and collaborating with providers. The program combines elements from 6 areas:

• psychoeducation

• cognitive-behavioral approaches to medication management and other treatment targets

• motivational interviewing

• relapse prevention planning

• social skills training

• coping skills to manage persistent symptoms.

The original curriculum, which is available free of charge, comprises 10 topics (Table).2 Of note, the newest version, IMR-3, includes an additional module focused on healthy lifestyles.3

Implementation

Although typically delivered as a structured weekly group intervention for 9 to 12 months, IMR can be taught individually. Involving a supportive person such as a family member, case manager, or residential staff member can be useful. Physicians can select modules tailored to the patient’s needs. Any physician who wants to bring IMR to her (his) patient can download the SAMHSA Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices KIT (Knowledge Informing Transformation).2 This free download provides the full curriculum with handouts, and tips and training tools related to implementation and evaluation of IMR in a typical mental health care setting.

IMR is well-accepted by most participants; studies report a median 63% of patients complete IMR.4 Attendance for the intervention appears to be better in a group, rather than an individual, format. A number of patient characteristics, including older age, lower hostility, fewer psychotic symptoms, and more education, have been identified as predictors of better attendance to manualized psychosocial treatments, such as IMR.5

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Patients with chronic illness, such as diabetes, are expected, and taught how, to participate in managing their disease. On the other hand, patients with serious mental illness historically have been thought of as passive recipients of care. Attitudes of care providers, patients, and family members are changing, however, and, in the last decade, the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) program has been developed for treating patients with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, using principles of chronic disease management.1 Consider using this evidence-based psychosocial treatment modality for your patients with schizophrenia.

Basic philosophy

A core assumption of IMR is realistic optimism that recovery is possible. Recovery, in this context, means that a patient can have a meaningful life despite having a serious illness. In IMR, patients engage in developing and tracking their progress toward personally meaningful goals; that progress is broken down into small steps and worked on over the course of the program.

Critical components

IMR addresses practical matters of living with schizophrenia, including coping with symptoms and collaborating with providers. The program combines elements from 6 areas:

• psychoeducation

• cognitive-behavioral approaches to medication management and other treatment targets

• motivational interviewing

• relapse prevention planning

• social skills training

• coping skills to manage persistent symptoms.

The original curriculum, which is available free of charge, comprises 10 topics (Table).2 Of note, the newest version, IMR-3, includes an additional module focused on healthy lifestyles.3

Implementation

Although typically delivered as a structured weekly group intervention for 9 to 12 months, IMR can be taught individually. Involving a supportive person such as a family member, case manager, or residential staff member can be useful. Physicians can select modules tailored to the patient’s needs. Any physician who wants to bring IMR to her (his) patient can download the SAMHSA Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices KIT (Knowledge Informing Transformation).2 This free download provides the full curriculum with handouts, and tips and training tools related to implementation and evaluation of IMR in a typical mental health care setting.

IMR is well-accepted by most participants; studies report a median 63% of patients complete IMR.4 Attendance for the intervention appears to be better in a group, rather than an individual, format. A number of patient characteristics, including older age, lower hostility, fewer psychotic symptoms, and more education, have been identified as predictors of better attendance to manualized psychosocial treatments, such as IMR.5

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(suppl 1):S32-S43.

2. SAMSHA. Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) KIT. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Illness-Management-and-Recovery-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA09-4463. Published March 2010. Accessed October 16, 2014.

3. Mueser KT, Gingerich S. Illness Management and Recovery. 3rd ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2011.

4. McGuire AB, Kukla M, Green A, et al. Illness management and recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):171-179.

5. McGuire AB, Bonfils KA, Kukla M, et al. Measuring participation in an evidence-based practice: illness management and recovery group attendance. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):684-689.

1. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al. The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(suppl 1):S32-S43.

2. SAMSHA. Illness Management and Recovery Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) KIT. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Illness-Management-and-Recovery-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA09-4463. Published March 2010. Accessed October 16, 2014.

3. Mueser KT, Gingerich S. Illness Management and Recovery. 3rd ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2011.

4. McGuire AB, Kukla M, Green A, et al. Illness management and recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):171-179.

5. McGuire AB, Bonfils KA, Kukla M, et al. Measuring participation in an evidence-based practice: illness management and recovery group attendance. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):684-689.

Clozapine: Talking about risks, benefits, and alternatives with patients

Clozapine is a life-saving medication for many patients with schizophrenia, including those who have a schizophrenia spectrum disorder with suicidality or treatment-resistant disease, but clinicians’ discomfort with managing its risk profile has led to it being underutilized. Clinicians who are prepared to discuss the risks and benefits of clozapine—and alternatives, including no treatment—with patients may encounter less reluctance when they recommend a time-limited trial of the drug.

Risks

Clinicians need to be aware of both 1) serious adverse effects that can occur when clozapine needs to be interrupted or discontinued (Table)1 and 2) common side effects associated with continued use that can be managed without stopping the drug.2 Common side effects that patients may experience as treatment is initiated include sedation, orthostatic hypotension, constipation, drooling, tachycardia, and metabolic side effects such as weight gain, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, which are problematic in the long term.

Reassure patients that frequent monitoring of metabolic metrics (including baseline HbA1C, lipid panel, waist circumference, and body mass index, as well as weight monitoring at each visit and metabolic laboratory monitoring every 3 to 6 months thereafter) should be expected, along with early intervention (eg, adding metformin) as appropriate. Constipation is common and can lead to serious, large bowel ileus. Ask about drooling, which can be treated by reducing the dosage or adding glycopyrrolate.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) including parkinsonism, dystonia, akathisia are uncommon (clozapine was the first “atypical” antipsychotic for this reason), but neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) can occur. Although tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a small risk, clozapine will improve established TD in many patients once they are switched to clozapine. Blood dyscrasias include granulocytopenia and the rare risk of agranulocytosis which are monitored by means of a prescribing registry. Myocarditis and pancreatitis are likely idiosyncratic immune-related side effects that are unique to clozapine among antipsychotics. Other dangerous side effects include a dosage-related risk of seizure, severe hyperglycemia, and diabetic ketoacidosis.

Benefits

Clozapine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for schizophrenia spectrum disorders with recurrent suicidality. Clozapine can be the best antipsychotic for patients who are sensitive to EPS and for those with TD. Antipsychotic efficacy often can be determined in a 2 to 3 month time-limited trial, although, in practice, you might need to wait 6 to 12 months to observe how well clozapine’s benefits have accrued.

Alternatives

Not using the most effective antipsychotic, or using no antipsychotic when one is indicated, often results in unstable psychiatric illness, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes (eg, suicide, accidents). Unstable psychiatric disease also complicates treatment of medical problems. An 11-year follow-up study in Finland of patients with schizophrenia showed a lower all-cause mortality with clozapine than with other antipsychotics, all of which collectively were associated with lower mortality compared with no antipsychotic use.3 Clozapine also is associated with the lowest discontinuation rate of any antipsychotic, which suggests that patients perceive its risk-benefit ratio favorably. Last, patients who might benefit from clozapine, but do not receive it, often will receive polypharmacy, which poses its own risks.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, et al. Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6): 603-613.

2. Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012.

3. Tiihonen J, Löngqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009; 374(9690):620-627.

Clozapine is a life-saving medication for many patients with schizophrenia, including those who have a schizophrenia spectrum disorder with suicidality or treatment-resistant disease, but clinicians’ discomfort with managing its risk profile has led to it being underutilized. Clinicians who are prepared to discuss the risks and benefits of clozapine—and alternatives, including no treatment—with patients may encounter less reluctance when they recommend a time-limited trial of the drug.

Risks

Clinicians need to be aware of both 1) serious adverse effects that can occur when clozapine needs to be interrupted or discontinued (Table)1 and 2) common side effects associated with continued use that can be managed without stopping the drug.2 Common side effects that patients may experience as treatment is initiated include sedation, orthostatic hypotension, constipation, drooling, tachycardia, and metabolic side effects such as weight gain, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, which are problematic in the long term.

Reassure patients that frequent monitoring of metabolic metrics (including baseline HbA1C, lipid panel, waist circumference, and body mass index, as well as weight monitoring at each visit and metabolic laboratory monitoring every 3 to 6 months thereafter) should be expected, along with early intervention (eg, adding metformin) as appropriate. Constipation is common and can lead to serious, large bowel ileus. Ask about drooling, which can be treated by reducing the dosage or adding glycopyrrolate.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) including parkinsonism, dystonia, akathisia are uncommon (clozapine was the first “atypical” antipsychotic for this reason), but neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) can occur. Although tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a small risk, clozapine will improve established TD in many patients once they are switched to clozapine. Blood dyscrasias include granulocytopenia and the rare risk of agranulocytosis which are monitored by means of a prescribing registry. Myocarditis and pancreatitis are likely idiosyncratic immune-related side effects that are unique to clozapine among antipsychotics. Other dangerous side effects include a dosage-related risk of seizure, severe hyperglycemia, and diabetic ketoacidosis.

Benefits

Clozapine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for schizophrenia spectrum disorders with recurrent suicidality. Clozapine can be the best antipsychotic for patients who are sensitive to EPS and for those with TD. Antipsychotic efficacy often can be determined in a 2 to 3 month time-limited trial, although, in practice, you might need to wait 6 to 12 months to observe how well clozapine’s benefits have accrued.

Alternatives

Not using the most effective antipsychotic, or using no antipsychotic when one is indicated, often results in unstable psychiatric illness, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes (eg, suicide, accidents). Unstable psychiatric disease also complicates treatment of medical problems. An 11-year follow-up study in Finland of patients with schizophrenia showed a lower all-cause mortality with clozapine than with other antipsychotics, all of which collectively were associated with lower mortality compared with no antipsychotic use.3 Clozapine also is associated with the lowest discontinuation rate of any antipsychotic, which suggests that patients perceive its risk-benefit ratio favorably. Last, patients who might benefit from clozapine, but do not receive it, often will receive polypharmacy, which poses its own risks.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Clozapine is a life-saving medication for many patients with schizophrenia, including those who have a schizophrenia spectrum disorder with suicidality or treatment-resistant disease, but clinicians’ discomfort with managing its risk profile has led to it being underutilized. Clinicians who are prepared to discuss the risks and benefits of clozapine—and alternatives, including no treatment—with patients may encounter less reluctance when they recommend a time-limited trial of the drug.

Risks

Clinicians need to be aware of both 1) serious adverse effects that can occur when clozapine needs to be interrupted or discontinued (Table)1 and 2) common side effects associated with continued use that can be managed without stopping the drug.2 Common side effects that patients may experience as treatment is initiated include sedation, orthostatic hypotension, constipation, drooling, tachycardia, and metabolic side effects such as weight gain, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, which are problematic in the long term.

Reassure patients that frequent monitoring of metabolic metrics (including baseline HbA1C, lipid panel, waist circumference, and body mass index, as well as weight monitoring at each visit and metabolic laboratory monitoring every 3 to 6 months thereafter) should be expected, along with early intervention (eg, adding metformin) as appropriate. Constipation is common and can lead to serious, large bowel ileus. Ask about drooling, which can be treated by reducing the dosage or adding glycopyrrolate.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) including parkinsonism, dystonia, akathisia are uncommon (clozapine was the first “atypical” antipsychotic for this reason), but neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) can occur. Although tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a small risk, clozapine will improve established TD in many patients once they are switched to clozapine. Blood dyscrasias include granulocytopenia and the rare risk of agranulocytosis which are monitored by means of a prescribing registry. Myocarditis and pancreatitis are likely idiosyncratic immune-related side effects that are unique to clozapine among antipsychotics. Other dangerous side effects include a dosage-related risk of seizure, severe hyperglycemia, and diabetic ketoacidosis.

Benefits

Clozapine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for schizophrenia spectrum disorders with recurrent suicidality. Clozapine can be the best antipsychotic for patients who are sensitive to EPS and for those with TD. Antipsychotic efficacy often can be determined in a 2 to 3 month time-limited trial, although, in practice, you might need to wait 6 to 12 months to observe how well clozapine’s benefits have accrued.

Alternatives

Not using the most effective antipsychotic, or using no antipsychotic when one is indicated, often results in unstable psychiatric illness, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes (eg, suicide, accidents). Unstable psychiatric disease also complicates treatment of medical problems. An 11-year follow-up study in Finland of patients with schizophrenia showed a lower all-cause mortality with clozapine than with other antipsychotics, all of which collectively were associated with lower mortality compared with no antipsychotic use.3 Clozapine also is associated with the lowest discontinuation rate of any antipsychotic, which suggests that patients perceive its risk-benefit ratio favorably. Last, patients who might benefit from clozapine, but do not receive it, often will receive polypharmacy, which poses its own risks.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, et al. Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6): 603-613.

2. Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012.

3. Tiihonen J, Löngqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009; 374(9690):620-627.

1. Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, et al. Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6): 603-613.

2. Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012.

3. Tiihonen J, Löngqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009; 374(9690):620-627.

In reference to “Discharge against medical advice: How often do we intervene?”

In their study of against medical advice (AMA) discharges, Edwards et al.[1] express surprise that prescriptions were given and follow‐up arranged at a much lower rate than the frequency of warning of impending AMA discharge. The authors assume that when doctors know a patient wants to leave AMA, they will and should, as a matter of course, write prescriptions and arrange follow‐up. Not considered is the possibility that doctors may decide for selected patients that the better response is not to prescribe and not to arrange follow‐up. Prescribing medications to a patient who has already shown disinterest in heeding doctors' advice may be considered dangerous. Similarly, making an appointment for a patient who has already demonstrated a lack of adherence, thereby depriving another patient of that appointment, may be considered an imprudent use of resources. The authors do not provide data on how many AMA discharges may have been averted by this approach. Attempts to minimize the negative impact of capable patients' decisions neglect that some patients do not categorically prioritize health, and that true autonomy entails not just decision making but bearing responsibility for those decisions' consequences. Medical risk reduction is not the only value at play in these complex situations.

- , , . Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):574–577.

In their study of against medical advice (AMA) discharges, Edwards et al.[1] express surprise that prescriptions were given and follow‐up arranged at a much lower rate than the frequency of warning of impending AMA discharge. The authors assume that when doctors know a patient wants to leave AMA, they will and should, as a matter of course, write prescriptions and arrange follow‐up. Not considered is the possibility that doctors may decide for selected patients that the better response is not to prescribe and not to arrange follow‐up. Prescribing medications to a patient who has already shown disinterest in heeding doctors' advice may be considered dangerous. Similarly, making an appointment for a patient who has already demonstrated a lack of adherence, thereby depriving another patient of that appointment, may be considered an imprudent use of resources. The authors do not provide data on how many AMA discharges may have been averted by this approach. Attempts to minimize the negative impact of capable patients' decisions neglect that some patients do not categorically prioritize health, and that true autonomy entails not just decision making but bearing responsibility for those decisions' consequences. Medical risk reduction is not the only value at play in these complex situations.

In their study of against medical advice (AMA) discharges, Edwards et al.[1] express surprise that prescriptions were given and follow‐up arranged at a much lower rate than the frequency of warning of impending AMA discharge. The authors assume that when doctors know a patient wants to leave AMA, they will and should, as a matter of course, write prescriptions and arrange follow‐up. Not considered is the possibility that doctors may decide for selected patients that the better response is not to prescribe and not to arrange follow‐up. Prescribing medications to a patient who has already shown disinterest in heeding doctors' advice may be considered dangerous. Similarly, making an appointment for a patient who has already demonstrated a lack of adherence, thereby depriving another patient of that appointment, may be considered an imprudent use of resources. The authors do not provide data on how many AMA discharges may have been averted by this approach. Attempts to minimize the negative impact of capable patients' decisions neglect that some patients do not categorically prioritize health, and that true autonomy entails not just decision making but bearing responsibility for those decisions' consequences. Medical risk reduction is not the only value at play in these complex situations.

- , , . Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):574–577.

- , , . Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):574–577.

Four questions to guide clinical decisions

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Psychiatrists often are asked to help medical colleagues deal with difficult patients. A typical situation involves a patient with a psychiatric diagnosis who refuses medical treatment. Asking 4 questions—adapted from the 4-quadrant model proffered by Jonsen et al1,2 for ethical decision making in medicine—will help you make pragmatic and helpful treatment recommendations.

1. What does psychiatry have to offer? Consider all the psychiatric facts:

- Are you treating a well-established psychiatric syndrome or mere symptoms?

- What are all your treatment options?

- Which psychiatric treatment would be optimal?

- What is the prognosis for each psychiatric intervention, including no treatment?

2. What does the patient want? Patient-centered medicine tries to work out a competent patient’s preferred course of action. Even for patients deemed incompetent and under court-ordered guardianship, find out what might be acceptable to avoid confrontations. For example, obtaining a guardian for a patient with dementia who refuses hemodialysis is pointless unless everyone involved is willing to restrain and sedate the patient 3 times weekly for the procedure.

3. What kind of life does the patient both hope for and fear? Quality of life features prominently in patients’ minds. Make sure you know how each of the proposed psychiatric interventions might affect the patient’s quality of life. Make explicit what the patient fears. For example, do not assume a patient with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome who wants to continue to live necessarily wants or is willing to take antiretroviral medications.

4. Who and what else matters? Clinical decision making does not occur in a vacuum. Many stakeholders (people and “systems”) will have legitimate concerns: family members will not take a patient back; hospital policies do not allow use of a particular drug; state laws must be obeyed. In addition, physicians have their own biases regarding what should or should not be done based on their worldview.

Asking these 4 questions in a structured way will not necessarily lead to “the solution.” It will, however, ensure that important areas to consider are all made explicit, and all stakeholders and their concerns were heard.

Disclosures

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and is a CME developer and speaker for Reed Medical Education.

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychiatric decision making: Applying the 4 key questions

Mr. A is a 55-year-old homeless man with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) who displays prominent disinhibition and witzelsucht—brain dysfunction marked by telling inappropriate or irrelevant jokes. He rarely misses clinic appointments and when acutely ill, seeks medical attention and cooperates with inpatient treatment. But he has a long pattern of poor adherence to HIV medications—in part as a result of being homeless—and mostly rejects outreach efforts (eg, visiting nurses to help with adherence); no arrangement has lasted more than a few months. Psychopharmacologic interventions have made no appreciable difference in Mr. A’s frontal impairment. He declines further treatment with psychotropic medications but agrees to take antiretroviral agents.

After Mr. A is diagnosed with thyroid cancer, the medical team recommends a total thyroidectomy; a partial thyroidectomy with close follow-up and a potential second surgery is discussed as a reasonable alternative. Mr. A opts for total thyroid removal.

Mr. A’s medical team asks you if he should be admitted to a psychiatric hospital to treat his disinhibition with the goal of improving his ability to adhere to a lifelong thyroid-replacement medication regimen.

Using the 4-Quadrant Method

1. What does psychiatry have to offer?

From the psychiatric viewpoint, the most critical feature is Mr. A’s “frontal lobe syndrome” with elements of disinhibition, executive dysfunction, and impairments in persistence and long-term planning, likely secondary to severe past alcohol and drug use and long-standing, poorly controlled HIV infection. This neurocognitive dysfunction has been stable for many years, which argues against a progressive process that could be interrupted. Although further trials of psychotropics could be proposed, it is uncertain if any intervention could improve Mr. A’s medication adherence. Even assuming a judge would authorize an involuntary admission and compulsory treatment—which would be required in Mr. A’s case because he has refused further psychiatric treatment—no psychiatric treatment would reverse his executive dysfunction in a reliable and timely manner. Better adherence to HIV medications might offer the best chance for improvement, but Mr. A would need to be in a supervised setting indefinitely, assuming such a setting exists and he agrees to be essentially immobilized.

One could argue Mr. A might be incapable of making some treatment decisions, but simply recommending and pursuing guardianship is not the purpose of this quadrant.

2. What does the patient want?

Mr. A’s preference is not to take psychotropic medications because none helped in the past. His medical choice is clear: to have a total thyroidectomy. He is afraid of dying, explaining, “I don’t want them to leave any cancer in there.”

3. What kind of life does the patient both hope for and fear?

Although Mr. A generally rejects excessive intrusion into his life by the medical profession, he nevertheless takes HIV medications (albeit intermittently), wants surgery, and says he will take thyroid replacement medications. He is willing to tackle the issues he fears. He readily agrees to curative surgery for his thyroid cancer because he fears nothing more than dying of cancer.

4. Who and what else matters?

Besides the patient, the 2 people who matter most are the primary care doctor and the endocrinologist, who are concerned about Mr. A’s ability to take thyroid replacement therapy reliably. Their shared concern is based on the patient’s history of intermittent adherence to antiretroviral medications. Family does not figure in to Mr. A’s situation, as it usually does in cases such as this when family members are available to help the patient negotiate medical decisions.

Recommendation

The crux of the analysis is recognizing that a psychiatric intervention in the form of medication trials—even if a first-line treatment were clear—would be of uncertain benefit and involuntary psychiatric hospitalization would not accomplish the long-term goal of remediating Mr. A’s executive dysfunction. In the final analysis, the patient’s medical team accepted Mr. A’s wish for optimal medical treatment now, while accepting the uncertainty of his ability to follow through later.

Clinical outcome

Mr. A underwent a successful total thyroidectomy and is believed to be cancer-free. He continues to work with his infectious diseases doctor and endocrinologist; as expected, his adherence to thyroid replacement has been suboptimal. However, through occasional “loading doses,” Mr. A has managed to remain only mildly hypothyroid with no clinical sequelae.

Current Psychiatry ©2011 Quadrant HealthCom Inc.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Psychiatrists often are asked to help medical colleagues deal with difficult patients. A typical situation involves a patient with a psychiatric diagnosis who refuses medical treatment. Asking 4 questions—adapted from the 4-quadrant model proffered by Jonsen et al1,2 for ethical decision making in medicine—will help you make pragmatic and helpful treatment recommendations.

1. What does psychiatry have to offer? Consider all the psychiatric facts:

- Are you treating a well-established psychiatric syndrome or mere symptoms?

- What are all your treatment options?

- Which psychiatric treatment would be optimal?

- What is the prognosis for each psychiatric intervention, including no treatment?

2. What does the patient want? Patient-centered medicine tries to work out a competent patient’s preferred course of action. Even for patients deemed incompetent and under court-ordered guardianship, find out what might be acceptable to avoid confrontations. For example, obtaining a guardian for a patient with dementia who refuses hemodialysis is pointless unless everyone involved is willing to restrain and sedate the patient 3 times weekly for the procedure.

3. What kind of life does the patient both hope for and fear? Quality of life features prominently in patients’ minds. Make sure you know how each of the proposed psychiatric interventions might affect the patient’s quality of life. Make explicit what the patient fears. For example, do not assume a patient with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome who wants to continue to live necessarily wants or is willing to take antiretroviral medications.

4. Who and what else matters? Clinical decision making does not occur in a vacuum. Many stakeholders (people and “systems”) will have legitimate concerns: family members will not take a patient back; hospital policies do not allow use of a particular drug; state laws must be obeyed. In addition, physicians have their own biases regarding what should or should not be done based on their worldview.

Asking these 4 questions in a structured way will not necessarily lead to “the solution.” It will, however, ensure that important areas to consider are all made explicit, and all stakeholders and their concerns were heard.

Disclosures

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and is a CME developer and speaker for Reed Medical Education.

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychiatric decision making: Applying the 4 key questions

Mr. A is a 55-year-old homeless man with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) who displays prominent disinhibition and witzelsucht—brain dysfunction marked by telling inappropriate or irrelevant jokes. He rarely misses clinic appointments and when acutely ill, seeks medical attention and cooperates with inpatient treatment. But he has a long pattern of poor adherence to HIV medications—in part as a result of being homeless—and mostly rejects outreach efforts (eg, visiting nurses to help with adherence); no arrangement has lasted more than a few months. Psychopharmacologic interventions have made no appreciable difference in Mr. A’s frontal impairment. He declines further treatment with psychotropic medications but agrees to take antiretroviral agents.

After Mr. A is diagnosed with thyroid cancer, the medical team recommends a total thyroidectomy; a partial thyroidectomy with close follow-up and a potential second surgery is discussed as a reasonable alternative. Mr. A opts for total thyroid removal.

Mr. A’s medical team asks you if he should be admitted to a psychiatric hospital to treat his disinhibition with the goal of improving his ability to adhere to a lifelong thyroid-replacement medication regimen.

Using the 4-Quadrant Method

1. What does psychiatry have to offer?

From the psychiatric viewpoint, the most critical feature is Mr. A’s “frontal lobe syndrome” with elements of disinhibition, executive dysfunction, and impairments in persistence and long-term planning, likely secondary to severe past alcohol and drug use and long-standing, poorly controlled HIV infection. This neurocognitive dysfunction has been stable for many years, which argues against a progressive process that could be interrupted. Although further trials of psychotropics could be proposed, it is uncertain if any intervention could improve Mr. A’s medication adherence. Even assuming a judge would authorize an involuntary admission and compulsory treatment—which would be required in Mr. A’s case because he has refused further psychiatric treatment—no psychiatric treatment would reverse his executive dysfunction in a reliable and timely manner. Better adherence to HIV medications might offer the best chance for improvement, but Mr. A would need to be in a supervised setting indefinitely, assuming such a setting exists and he agrees to be essentially immobilized.

One could argue Mr. A might be incapable of making some treatment decisions, but simply recommending and pursuing guardianship is not the purpose of this quadrant.

2. What does the patient want?

Mr. A’s preference is not to take psychotropic medications because none helped in the past. His medical choice is clear: to have a total thyroidectomy. He is afraid of dying, explaining, “I don’t want them to leave any cancer in there.”

3. What kind of life does the patient both hope for and fear?

Although Mr. A generally rejects excessive intrusion into his life by the medical profession, he nevertheless takes HIV medications (albeit intermittently), wants surgery, and says he will take thyroid replacement medications. He is willing to tackle the issues he fears. He readily agrees to curative surgery for his thyroid cancer because he fears nothing more than dying of cancer.

4. Who and what else matters?

Besides the patient, the 2 people who matter most are the primary care doctor and the endocrinologist, who are concerned about Mr. A’s ability to take thyroid replacement therapy reliably. Their shared concern is based on the patient’s history of intermittent adherence to antiretroviral medications. Family does not figure in to Mr. A’s situation, as it usually does in cases such as this when family members are available to help the patient negotiate medical decisions.

Recommendation

The crux of the analysis is recognizing that a psychiatric intervention in the form of medication trials—even if a first-line treatment were clear—would be of uncertain benefit and involuntary psychiatric hospitalization would not accomplish the long-term goal of remediating Mr. A’s executive dysfunction. In the final analysis, the patient’s medical team accepted Mr. A’s wish for optimal medical treatment now, while accepting the uncertainty of his ability to follow through later.

Clinical outcome

Mr. A underwent a successful total thyroidectomy and is believed to be cancer-free. He continues to work with his infectious diseases doctor and endocrinologist; as expected, his adherence to thyroid replacement has been suboptimal. However, through occasional “loading doses,” Mr. A has managed to remain only mildly hypothyroid with no clinical sequelae.

Current Psychiatry ©2011 Quadrant HealthCom Inc.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Psychiatrists often are asked to help medical colleagues deal with difficult patients. A typical situation involves a patient with a psychiatric diagnosis who refuses medical treatment. Asking 4 questions—adapted from the 4-quadrant model proffered by Jonsen et al1,2 for ethical decision making in medicine—will help you make pragmatic and helpful treatment recommendations.

1. What does psychiatry have to offer? Consider all the psychiatric facts:

- Are you treating a well-established psychiatric syndrome or mere symptoms?

- What are all your treatment options?

- Which psychiatric treatment would be optimal?

- What is the prognosis for each psychiatric intervention, including no treatment?

2. What does the patient want? Patient-centered medicine tries to work out a competent patient’s preferred course of action. Even for patients deemed incompetent and under court-ordered guardianship, find out what might be acceptable to avoid confrontations. For example, obtaining a guardian for a patient with dementia who refuses hemodialysis is pointless unless everyone involved is willing to restrain and sedate the patient 3 times weekly for the procedure.

3. What kind of life does the patient both hope for and fear? Quality of life features prominently in patients’ minds. Make sure you know how each of the proposed psychiatric interventions might affect the patient’s quality of life. Make explicit what the patient fears. For example, do not assume a patient with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome who wants to continue to live necessarily wants or is willing to take antiretroviral medications.

4. Who and what else matters? Clinical decision making does not occur in a vacuum. Many stakeholders (people and “systems”) will have legitimate concerns: family members will not take a patient back; hospital policies do not allow use of a particular drug; state laws must be obeyed. In addition, physicians have their own biases regarding what should or should not be done based on their worldview.

Asking these 4 questions in a structured way will not necessarily lead to “the solution.” It will, however, ensure that important areas to consider are all made explicit, and all stakeholders and their concerns were heard.

Disclosures

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and is a CME developer and speaker for Reed Medical Education.

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychiatric decision making: Applying the 4 key questions

Mr. A is a 55-year-old homeless man with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) who displays prominent disinhibition and witzelsucht—brain dysfunction marked by telling inappropriate or irrelevant jokes. He rarely misses clinic appointments and when acutely ill, seeks medical attention and cooperates with inpatient treatment. But he has a long pattern of poor adherence to HIV medications—in part as a result of being homeless—and mostly rejects outreach efforts (eg, visiting nurses to help with adherence); no arrangement has lasted more than a few months. Psychopharmacologic interventions have made no appreciable difference in Mr. A’s frontal impairment. He declines further treatment with psychotropic medications but agrees to take antiretroviral agents.

After Mr. A is diagnosed with thyroid cancer, the medical team recommends a total thyroidectomy; a partial thyroidectomy with close follow-up and a potential second surgery is discussed as a reasonable alternative. Mr. A opts for total thyroid removal.

Mr. A’s medical team asks you if he should be admitted to a psychiatric hospital to treat his disinhibition with the goal of improving his ability to adhere to a lifelong thyroid-replacement medication regimen.

Using the 4-Quadrant Method

1. What does psychiatry have to offer?

From the psychiatric viewpoint, the most critical feature is Mr. A’s “frontal lobe syndrome” with elements of disinhibition, executive dysfunction, and impairments in persistence and long-term planning, likely secondary to severe past alcohol and drug use and long-standing, poorly controlled HIV infection. This neurocognitive dysfunction has been stable for many years, which argues against a progressive process that could be interrupted. Although further trials of psychotropics could be proposed, it is uncertain if any intervention could improve Mr. A’s medication adherence. Even assuming a judge would authorize an involuntary admission and compulsory treatment—which would be required in Mr. A’s case because he has refused further psychiatric treatment—no psychiatric treatment would reverse his executive dysfunction in a reliable and timely manner. Better adherence to HIV medications might offer the best chance for improvement, but Mr. A would need to be in a supervised setting indefinitely, assuming such a setting exists and he agrees to be essentially immobilized.

One could argue Mr. A might be incapable of making some treatment decisions, but simply recommending and pursuing guardianship is not the purpose of this quadrant.

2. What does the patient want?

Mr. A’s preference is not to take psychotropic medications because none helped in the past. His medical choice is clear: to have a total thyroidectomy. He is afraid of dying, explaining, “I don’t want them to leave any cancer in there.”

3. What kind of life does the patient both hope for and fear?

Although Mr. A generally rejects excessive intrusion into his life by the medical profession, he nevertheless takes HIV medications (albeit intermittently), wants surgery, and says he will take thyroid replacement medications. He is willing to tackle the issues he fears. He readily agrees to curative surgery for his thyroid cancer because he fears nothing more than dying of cancer.

4. Who and what else matters?

Besides the patient, the 2 people who matter most are the primary care doctor and the endocrinologist, who are concerned about Mr. A’s ability to take thyroid replacement therapy reliably. Their shared concern is based on the patient’s history of intermittent adherence to antiretroviral medications. Family does not figure in to Mr. A’s situation, as it usually does in cases such as this when family members are available to help the patient negotiate medical decisions.

Recommendation

The crux of the analysis is recognizing that a psychiatric intervention in the form of medication trials—even if a first-line treatment were clear—would be of uncertain benefit and involuntary psychiatric hospitalization would not accomplish the long-term goal of remediating Mr. A’s executive dysfunction. In the final analysis, the patient’s medical team accepted Mr. A’s wish for optimal medical treatment now, while accepting the uncertainty of his ability to follow through later.

Clinical outcome

Mr. A underwent a successful total thyroidectomy and is believed to be cancer-free. He continues to work with his infectious diseases doctor and endocrinologist; as expected, his adherence to thyroid replacement has been suboptimal. However, through occasional “loading doses,” Mr. A has managed to remain only mildly hypothyroid with no clinical sequelae.

Current Psychiatry ©2011 Quadrant HealthCom Inc.

The ABCs of estimating adherence to antipsychotics

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

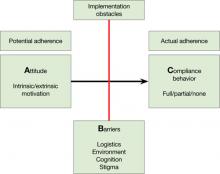

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?

Expect a positive drug attitude if the medication is perceived as warranted, potentially effective, and tolerable. Inquire about prior experience with medications and psychiatrists, including unpleasant somatic experiences, periods of coercion, specific benefits, and fears. Remember that the perceived harm from—vs the perceived need for—medications is judged from the patient’s point of view, not the clinician’s. For example, some patients are motivated to take an antipsychotic because it helps them sleep. Make note if motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic. You might start by asking, “Why do you think taking this medication is a good idea?”

Figure: Attitude, Barriers, and Compliance behavior

B Are there Barriers for a motivated patient to implement optimal adherence?

Ask, “What gets in the way of taking your medication?” Identifying barriers for the motivated patient forces you to look at the individual’s real-life situation. Can the patient afford the co-pay? Is the family against the patient taking an antipsychotic? Does the patient lack a routine that would help him or her remember to take pills? Is the patient too ashamed of the stigma of taking psychiatric medications? Does the patient have cognitive impairment that leads to forgetting to take pills?

C What is my best quantitative estimate of Compliance behavior?

Ask your patient, “In the last 7 days, how many pills have you missed?” Inquire also about names of pills and dosages, number of pills prescribed, and how they are taken to get a sense of your patient’s routines and cognitive competence. This is the time to get collateral information, such as when the last prescription was filled. After collecting this information, you should be able to estimate a patient’s level of adherence (eg, almost 100%, partial 50% to 75%, none). Be aware that both clinicians and patients overestimate actual adherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Kontos and Querques report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freudenreich receives grant/research support from Pfizer Inc. He is a consultant to Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Beacon Health Strategies, LLC and a speaker for Reed Medical Education.

1. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):1-46.

Adequate adherence to antipsychotics is critical for most patients with a chronic psychotic disorder. Therefore, appraisal of medication adherence—also called compliance in the older literature—is crucial at all visits.

Medication adherence is both an attitude and a behavior,1 and you need to assess both. Without some motivation to take medications (ie, a positive drug attitude), adherence is unlikely. On the other hand, motivation alone does not guarantee compliance behavior, and you need to assess barriers to adherence even in motivated patients.

To arrive at a clinical estimate of adherence to antipsychotics, ask yourself:

A What is my patient’s Attitude toward antipsychotics?