User login

“Just relax, stop thinking about it and, more than likely, it will happen.” If ever there was a controversial subject in medicine, especially in reproduction, the relationship between stress and infertility would be high on the list. Who among us has not overheard or even personally shared with an infertility patient that they should try and reduce their stress to improve fertility? The theory is certainly not new. Hippocrates, back in the 5th century B.C., was one of the first to associate a woman’s psychological state with her reproductive potential. His contention was that a physical sign of psychological stress in women (which scholars later dubbed “hysteria”) could result in sterility. In medieval times, a German abbess and mystic named Hildegard of Bingen posited women suffering from melancholy – a condition that we today might call depression – were infertile as a result.

The deeper meaning behind the flippant advice to relax is implicit blame; that is, a woman interprets the link of stress and infertility as a declaration that she is sabotaging reproduction. Not only is this assumption flawed, but it does further damage to a woman’s emotional fragility. To provide the presumption of stress affecting reproduction, a recent survey of over 5,000 infertility patients found, remarkably, 98% considered emotional stress as either a cause or a contributor to infertility, and 31% believed stress was a cause of miscarriage, although racial differences existed (J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021 Apr;38[4]:877-87). This relationship was mostly seen in women who used complementary and alternative medicine, Black women, and those who frequented Internet search engines. Whereas women who had a professional degree, had more infertility insurance coverage, and were nonreligious were less likely to attribute stress to infertility. Intriguingly, the more engaged the physicians, the less patients linked stress with infertility, while the contrary also applied.

The power of stress can be exemplified by the pathophysiology of amenorrhea. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is the most common cause of the female athlete triad of secondary amenorrhea in women of childbearing age. It is a reversible disorder caused by stress related to weight loss, excessive exercise and/or traumatic mental experiences (Endocrines. 2021;2:203-11). Stress of infertility has also been demonstrated to be equivalent to a diagnosis of cancer and other major medical morbidities (J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;14[Suppl]:45-52).

A definitive link between stress and infertility is evasive because of the lack of controlled, prospective longitudinal studies and the challenge of reducing variables in the analysis. The question remains which developed initially – the stress or the infertility? Infertility treatment is a physical, emotional, and financial investment. Stress and the duration of infertility are correlative. The additive factor is that poor insurance coverage for costly fertility treatment can not only heighten stress but, concurrently, subject the patient to the risk of exploitation driven by desperation whereby they accept unproven “add-ons” offered with assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Both acute and chronic stress affect the number of oocytes retrieved and fertilized with ART as well as live birth delivery and birth weights (Fertil Steril. 2001;76:675-87). Men are also affected by stress, which is manifested by decreased libido and impaired semen, further compromised as the duration of infertility continues. The gut-derived hormone ghrelin appears to play a role with stress and reproduction (Endocr Rev. 2017;38:432-67).

As the relationship between stress and infertility is far from proven, there are conflicting study results. Two meta-analyses failed to show any association between stress and the outcomes of ART cycles (Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2763-76; BMJ. 2011;342:d223). In contrast, a recent study suggested stress during infertility treatment was contributed by the variables of low spousal support, financial constraints, and social coercion in the early years of marriage (J Hum Reprod Sci. 2018;11:172-9). Emotional distress was found to be three times greater in women whose families had unrealistic expectations from treatments.

Fortunately, psychotherapy during the ART cycle has demonstrated a benefit in outcomes. Domar revealed psychological support and cognitive behavior therapy resulted in higher pregnancy rates than in the control group (Fertil Steril. 2000;73:805-12). Another recent study appears to support stress reduction improving reproductive potential (Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20[1]:41-7).

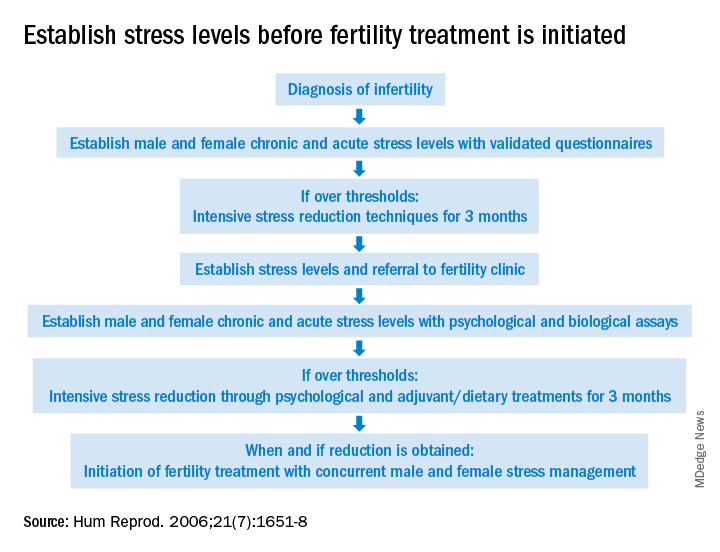

Given the evidence provided in this article, it behooves infertility clinics to address baseline (chronic) stress and acute stress (because of infertility) prior to initiating treatment (see Figure). While the definitive answer addressing the impact of stress on reproduction remains unknown, we may share with our patients a definition in which they may find enlightenment, “Stress is trying to control an event in which one is incapable.”

Dr. Mark P Trolice is director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

“Just relax, stop thinking about it and, more than likely, it will happen.” If ever there was a controversial subject in medicine, especially in reproduction, the relationship between stress and infertility would be high on the list. Who among us has not overheard or even personally shared with an infertility patient that they should try and reduce their stress to improve fertility? The theory is certainly not new. Hippocrates, back in the 5th century B.C., was one of the first to associate a woman’s psychological state with her reproductive potential. His contention was that a physical sign of psychological stress in women (which scholars later dubbed “hysteria”) could result in sterility. In medieval times, a German abbess and mystic named Hildegard of Bingen posited women suffering from melancholy – a condition that we today might call depression – were infertile as a result.

The deeper meaning behind the flippant advice to relax is implicit blame; that is, a woman interprets the link of stress and infertility as a declaration that she is sabotaging reproduction. Not only is this assumption flawed, but it does further damage to a woman’s emotional fragility. To provide the presumption of stress affecting reproduction, a recent survey of over 5,000 infertility patients found, remarkably, 98% considered emotional stress as either a cause or a contributor to infertility, and 31% believed stress was a cause of miscarriage, although racial differences existed (J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021 Apr;38[4]:877-87). This relationship was mostly seen in women who used complementary and alternative medicine, Black women, and those who frequented Internet search engines. Whereas women who had a professional degree, had more infertility insurance coverage, and were nonreligious were less likely to attribute stress to infertility. Intriguingly, the more engaged the physicians, the less patients linked stress with infertility, while the contrary also applied.

The power of stress can be exemplified by the pathophysiology of amenorrhea. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is the most common cause of the female athlete triad of secondary amenorrhea in women of childbearing age. It is a reversible disorder caused by stress related to weight loss, excessive exercise and/or traumatic mental experiences (Endocrines. 2021;2:203-11). Stress of infertility has also been demonstrated to be equivalent to a diagnosis of cancer and other major medical morbidities (J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;14[Suppl]:45-52).

A definitive link between stress and infertility is evasive because of the lack of controlled, prospective longitudinal studies and the challenge of reducing variables in the analysis. The question remains which developed initially – the stress or the infertility? Infertility treatment is a physical, emotional, and financial investment. Stress and the duration of infertility are correlative. The additive factor is that poor insurance coverage for costly fertility treatment can not only heighten stress but, concurrently, subject the patient to the risk of exploitation driven by desperation whereby they accept unproven “add-ons” offered with assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Both acute and chronic stress affect the number of oocytes retrieved and fertilized with ART as well as live birth delivery and birth weights (Fertil Steril. 2001;76:675-87). Men are also affected by stress, which is manifested by decreased libido and impaired semen, further compromised as the duration of infertility continues. The gut-derived hormone ghrelin appears to play a role with stress and reproduction (Endocr Rev. 2017;38:432-67).

As the relationship between stress and infertility is far from proven, there are conflicting study results. Two meta-analyses failed to show any association between stress and the outcomes of ART cycles (Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2763-76; BMJ. 2011;342:d223). In contrast, a recent study suggested stress during infertility treatment was contributed by the variables of low spousal support, financial constraints, and social coercion in the early years of marriage (J Hum Reprod Sci. 2018;11:172-9). Emotional distress was found to be three times greater in women whose families had unrealistic expectations from treatments.

Fortunately, psychotherapy during the ART cycle has demonstrated a benefit in outcomes. Domar revealed psychological support and cognitive behavior therapy resulted in higher pregnancy rates than in the control group (Fertil Steril. 2000;73:805-12). Another recent study appears to support stress reduction improving reproductive potential (Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20[1]:41-7).

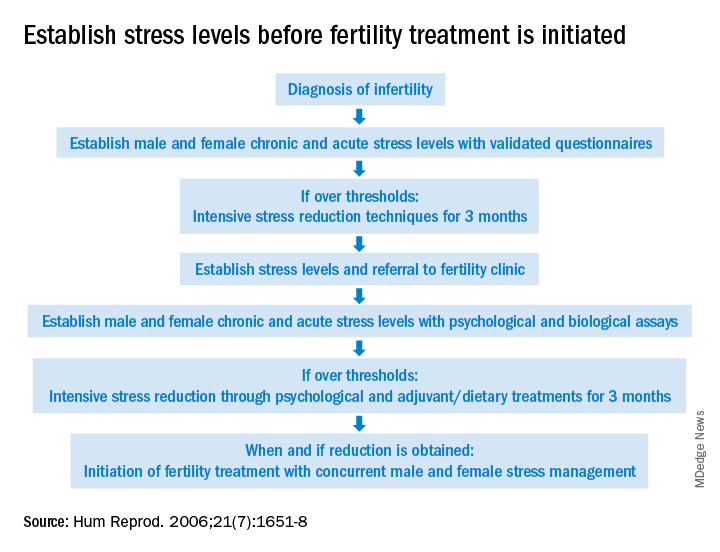

Given the evidence provided in this article, it behooves infertility clinics to address baseline (chronic) stress and acute stress (because of infertility) prior to initiating treatment (see Figure). While the definitive answer addressing the impact of stress on reproduction remains unknown, we may share with our patients a definition in which they may find enlightenment, “Stress is trying to control an event in which one is incapable.”

Dr. Mark P Trolice is director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

“Just relax, stop thinking about it and, more than likely, it will happen.” If ever there was a controversial subject in medicine, especially in reproduction, the relationship between stress and infertility would be high on the list. Who among us has not overheard or even personally shared with an infertility patient that they should try and reduce their stress to improve fertility? The theory is certainly not new. Hippocrates, back in the 5th century B.C., was one of the first to associate a woman’s psychological state with her reproductive potential. His contention was that a physical sign of psychological stress in women (which scholars later dubbed “hysteria”) could result in sterility. In medieval times, a German abbess and mystic named Hildegard of Bingen posited women suffering from melancholy – a condition that we today might call depression – were infertile as a result.

The deeper meaning behind the flippant advice to relax is implicit blame; that is, a woman interprets the link of stress and infertility as a declaration that she is sabotaging reproduction. Not only is this assumption flawed, but it does further damage to a woman’s emotional fragility. To provide the presumption of stress affecting reproduction, a recent survey of over 5,000 infertility patients found, remarkably, 98% considered emotional stress as either a cause or a contributor to infertility, and 31% believed stress was a cause of miscarriage, although racial differences existed (J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021 Apr;38[4]:877-87). This relationship was mostly seen in women who used complementary and alternative medicine, Black women, and those who frequented Internet search engines. Whereas women who had a professional degree, had more infertility insurance coverage, and were nonreligious were less likely to attribute stress to infertility. Intriguingly, the more engaged the physicians, the less patients linked stress with infertility, while the contrary also applied.

The power of stress can be exemplified by the pathophysiology of amenorrhea. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is the most common cause of the female athlete triad of secondary amenorrhea in women of childbearing age. It is a reversible disorder caused by stress related to weight loss, excessive exercise and/or traumatic mental experiences (Endocrines. 2021;2:203-11). Stress of infertility has also been demonstrated to be equivalent to a diagnosis of cancer and other major medical morbidities (J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;14[Suppl]:45-52).

A definitive link between stress and infertility is evasive because of the lack of controlled, prospective longitudinal studies and the challenge of reducing variables in the analysis. The question remains which developed initially – the stress or the infertility? Infertility treatment is a physical, emotional, and financial investment. Stress and the duration of infertility are correlative. The additive factor is that poor insurance coverage for costly fertility treatment can not only heighten stress but, concurrently, subject the patient to the risk of exploitation driven by desperation whereby they accept unproven “add-ons” offered with assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Both acute and chronic stress affect the number of oocytes retrieved and fertilized with ART as well as live birth delivery and birth weights (Fertil Steril. 2001;76:675-87). Men are also affected by stress, which is manifested by decreased libido and impaired semen, further compromised as the duration of infertility continues. The gut-derived hormone ghrelin appears to play a role with stress and reproduction (Endocr Rev. 2017;38:432-67).

As the relationship between stress and infertility is far from proven, there are conflicting study results. Two meta-analyses failed to show any association between stress and the outcomes of ART cycles (Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2763-76; BMJ. 2011;342:d223). In contrast, a recent study suggested stress during infertility treatment was contributed by the variables of low spousal support, financial constraints, and social coercion in the early years of marriage (J Hum Reprod Sci. 2018;11:172-9). Emotional distress was found to be three times greater in women whose families had unrealistic expectations from treatments.

Fortunately, psychotherapy during the ART cycle has demonstrated a benefit in outcomes. Domar revealed psychological support and cognitive behavior therapy resulted in higher pregnancy rates than in the control group (Fertil Steril. 2000;73:805-12). Another recent study appears to support stress reduction improving reproductive potential (Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20[1]:41-7).

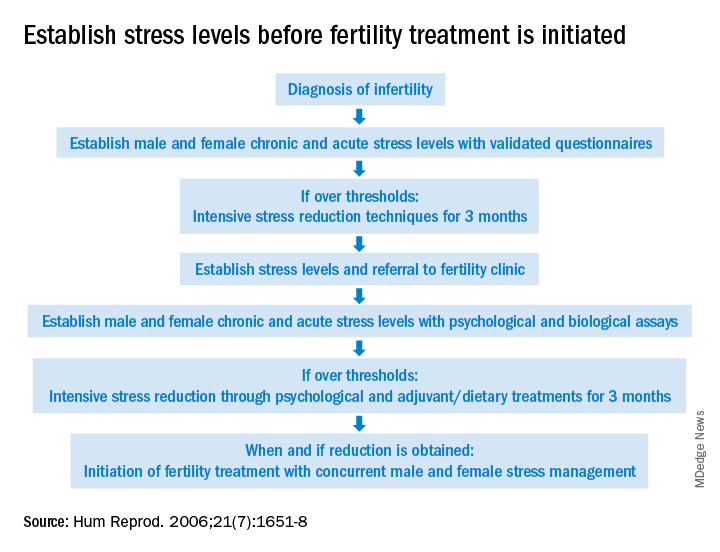

Given the evidence provided in this article, it behooves infertility clinics to address baseline (chronic) stress and acute stress (because of infertility) prior to initiating treatment (see Figure). While the definitive answer addressing the impact of stress on reproduction remains unknown, we may share with our patients a definition in which they may find enlightenment, “Stress is trying to control an event in which one is incapable.”

Dr. Mark P Trolice is director of Fertility CARE: The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.