User login

The American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) selected sulfites as the 2024 Allergen of the Year.1 Due to their preservative and antioxidant properties, sulfites are prevalent in a variety of foods, beverages, medications, and personal care products; however, sulfites also have been implicated as a potential contact allergen. In this article, we review common sources of sulfite exposure, clinical manifestations of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to sulfites, and patch testing considerations for this emerging allergen.

What Are Sulfites?

Sulfiting agents are compounds that contain the sulfite ion SO32-, including sulfur dioxide, sodium disulfite (sodium metabisulfite), and potassium metabisulfite.2 Sulfites occur naturally in the environment and commonly are used as preservatives, antibrowning agents, and antioxidants in various foods, beverages, medications, cosmetics, and skin care products. As antibrowning agents and antioxidants, sulfites help maintain the natural appearance of foods and other products and prevent premature spoiling by inactivating oxidative enzymes.3 It should be noted that sulfites and sulfates are distinct and unrelated compounds that do not cross-react.1

Common Sources of Sulfite Exposure

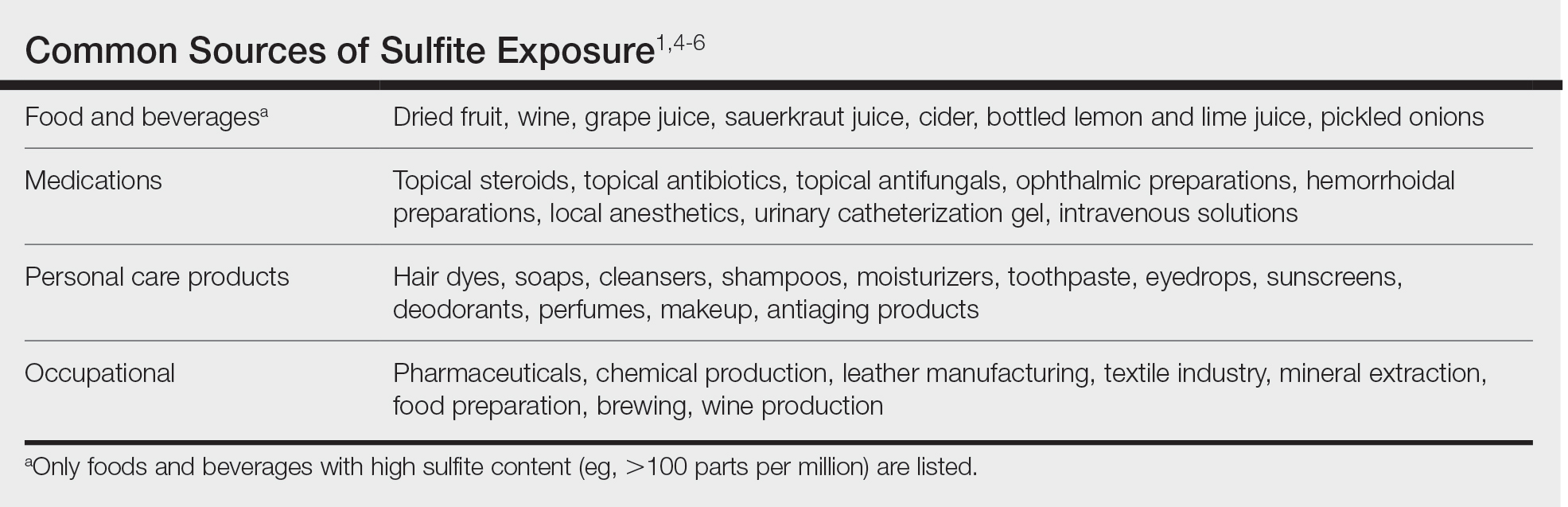

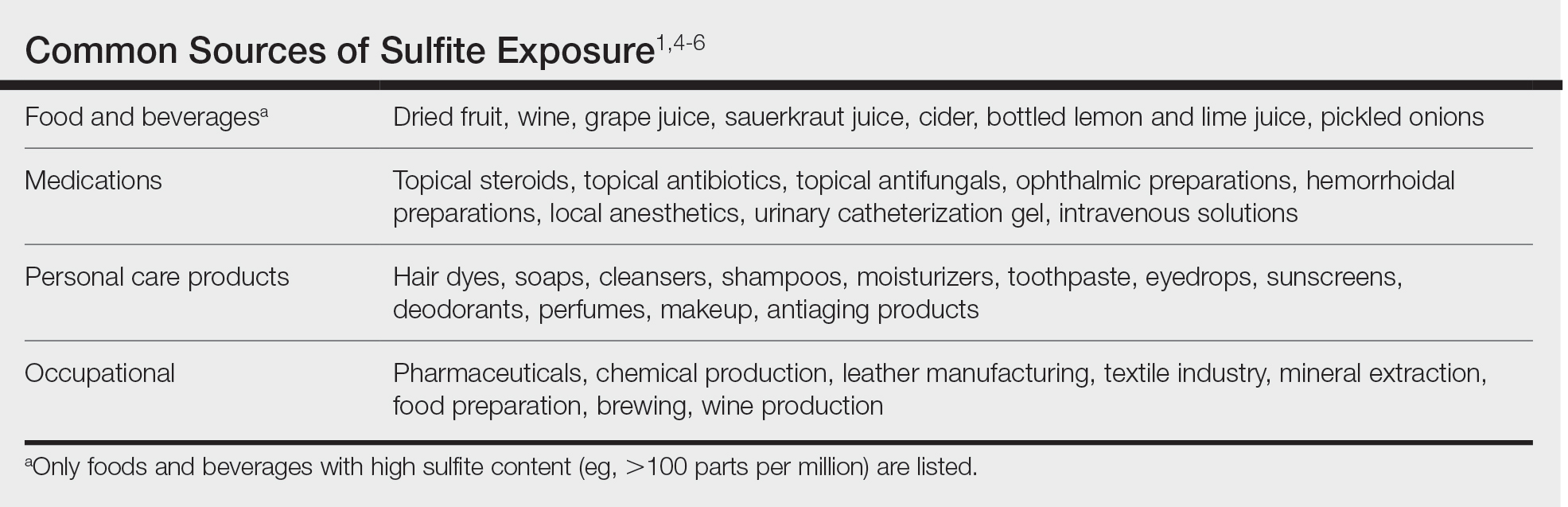

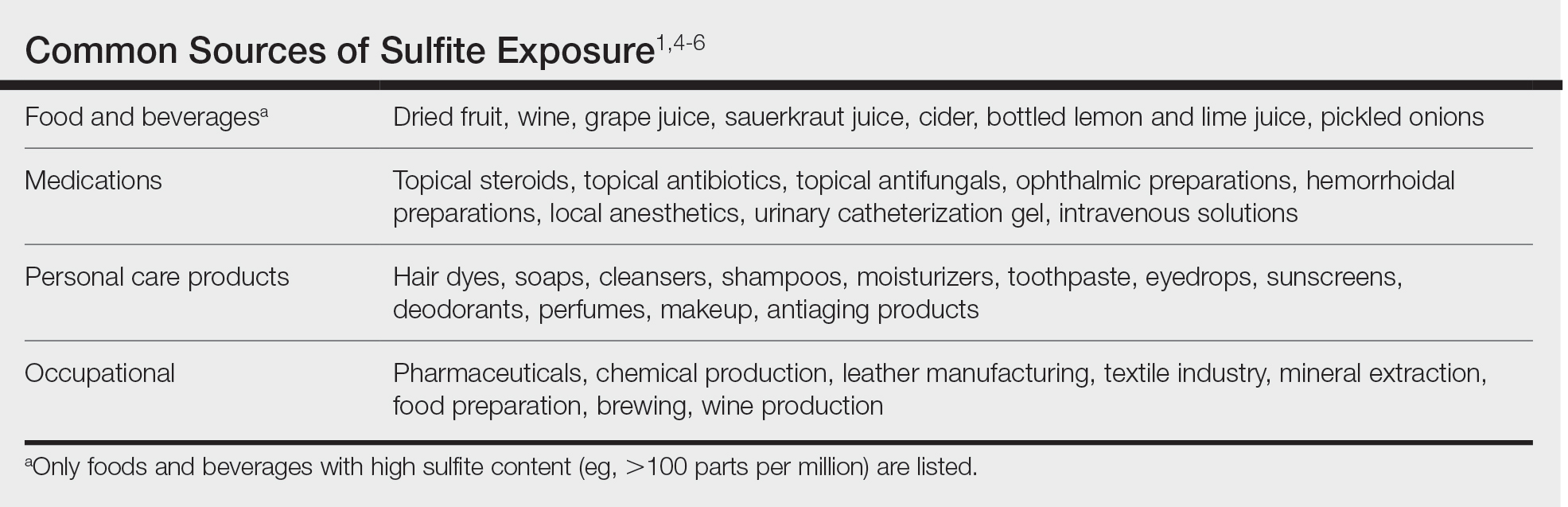

From a morning glass of juice to an evening shower, in the pharmacy and at the hair salon, sulfite exposure is ubiquitous in most daily routines. Sulfites are present in many foods and beverages, either as a byproduct of natural fermentation or as an additive to prevent spoiling and color change. The Table provides examples of foods with high sulfite content.1,4-6 In particular, dried fruit, bottled lemon juice, wine, grape juice, sauerkraut juice, and pickled onions have high sulfite content.

Topical medications and personal care products represent other potential sources of sulfite exposure. A number of reports have shown that sulfites may be included in topical steroids,7 antibiotics,8 antifungals,9 hemorrhoidal preparations,10 local anesthetics,11 and urinary catheterization gel,12 highlighting their many potential applications. In addition, a comprehensive ingredient analysis of 264 ophthalmic medications found that 3.8% of the products contained sodium disulfite.13 Sulfites may be found in personal care products, including facial and hand cleansers, shampoos, moisturizers, and toothpastes. Hair dyes also commonly contain sulfites,7 which are listed in as many as 90% of hair dye kits in the ACDS Contact Allergen Management Program database.1

Occupational exposures also are widespread, as sulfites are extensively utilized across diverse industries such as pharmaceuticals, health care, leather manufacturing, mineral extraction, food preparation, chemical manufacturing, textiles, alcohol brewing, and wine production.1

Sulfites also are used in the rubber industry—particularly in gloves—due to their anticoagulant and preservative properties.4 This is relevant to health care providers, who may use dozens of disposable gloves in a single day. In an experimental pilot study, researchers detected sulfites in 83% (5/6) of natural rubber latex gloves, 96% (23/24) of synthetic (nitrile) gloves, and 0% (0/5) of polyvinyl chloride gloves.14 While this study was limited to a small sample size, it demonstrates the common use of sulfites in certain rubber gloves and encourages future studies to determine whether there is a quantitative threshold to elicit allergic reactions.

Sulfite Allergy

In 1968, an early case report of ACD to sulfites was published involving a pharmaceutical worker who developed hand eczema after working at a factory for 3 months and had a positive patch test to potassium metabisulfite.15 There have been other cases published in the literature since then, including localized ACD as well as less common cases of systemic contact dermatitis following oral, injectable, and rectal sulfite exposures.16

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group found that, among 132 (2.7%) of 4885 patients with positive patch tests to sodium disulfite from 2017 to 2018, the most commonly involved body sites were the face (28.8%) and hands (20.5%) followed by a scattered/generalized distribution (13.6%). Involvement of the face and hands may correlate with the most frequent sources of exposure that were identified, including personal care products (particularly hair dyes)(18.9%), medications (9.1%), and foods (7.6%).17 A multicenter analysis of patch test results from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland from 1999 to 2013 showed that 357 (2.9%) of 12,156 patients had positive reactions to sodium disulfite, with the most commonly identified exposure sources being topical pharmaceutical agents (59.3%); cosmetics, creams, and sunscreens (13.6%); and systemic drugs (6.8%).18 However, it is not always possible to determine the clinical relevance of a positive patch test to sulfites.1

Other than the face and hands, there have been other unexpected anatomic locations for sulfite ACD (eg, the lower back), and systemic contact dermatitis has manifested with widespread rashes due to oral, rectal, and parenteral exposure.4,16,19 There is no definitive link between sulfite contact allergy and patient sex, but there seems to be a higher prevalence in patients older than 40 years, perhaps related to overall lifetime exposure.1

Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to sulfites also have been reported, including urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis.4 Due to multiple cases of severe dermatologic and respiratory reactions to food products containing sulfites,20 the US Food and Drug Administration prohibited their use in fresh fruit and vegetables as antibrowning agents in 1986 and required labels on packaged foods that contained sulfites at more than 10 parts per million.21 However, food and drinks produced in restaurants, bakeries, and cafes as well as those that are distributed directly to consumers from the preparation site are exempt from these rules.17

In addition, consuming high amounts of dietary sulfites has been linked to headaches through unclear (ie, not necessarily allergic) mechanisms.4,22 One study found that wine with a higher sulfite concentration was associated with increased risk for headaches in participants who had a history of headaches related to wine consumption.22

Patch Testing to Sulfites

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group has tested sodium disulfite since 2017 and found an increased frequency of positive patch tests from 2.7% (N=4885) in 2017 and 201817 to 3.3% (N=4115) in 2019 and 202023 among patients referred for testing. Similarly, patch testing to sodium disulfite in nearly 40,000 patients in 9 European countries showed a pooled prevalence of reactions of 3.1%.17 However, this contact allergy may go unrecognized, as sulfites are not included in common patch test series, including the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous test and the ACDS Core Allergen Series.24,25 The relatively high patch test positivity to sulfites along with the prevalence of daily exposures supports the addition of sulfites to more patch test screening series.

The recommended patch test concentration for sodium disulfite is 1% in petrolatum.5 Testing in aqueous solutions is not recommended because they can cause sulfites to break down, potentially producing false-positive or irritant patch test reactions.7,26,27

Recommendations for Patients With Sulfite Allergies

Individuals with contact allergies to sulfites should be counseled on exposure sources and should be given resources providing a list of safe products, such as the ACDS Contact Allergen Management Program (https://www.acdscamp.org/login) or SkinSAFE (https://www.skinsafeproducts.com/). Prescribers should be cognizant of sulfites that are present in prescription medications. Just because a patient has a positive patch test to sulfites does not automatically imply that they will need to modify their diet to avoid sulfite-containing foods; in the absence of cheilitis or a distribution suggestive of systemic contact dermatitis (eg, vesicular hand/foot dermatitis, intertriginous eruptions), this step may be unnecessary. On the other hand, individuals who have experienced immediate hypersensitivity reactions to sulfites should avoid sulfite-containing foods and carry an epinephrine autoinjector.

Final Interpretation

Sulfites are ubiquitous compounds found in various foods, beverages, medications, and personal care products in addition to a range of occupational exposures. The face and hands are the most common sites of sulfite ACD. Despite patch test positivity in as many as 3% of tested patients,17,23 sulfite allergy may be missed due to lack of routine testing on standard screening series.

- Ekstein SF, Warshaw EM. Sulfites: allergen of the year 2024. Dermatitis. 2024;35:6-12. doi:10.1089/derm.2023.0154

- Gunnison AF, Jacobsen DW. Sulfite hypersensitivity. a critical review. CRC Crit Rev Toxicol. 1987;17:185-214. doi:10.3109/10408448709071208

- Clough SR. Sodium sulfite. In: Wexler P, ed. Encyclopedia of Toxicology. 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2014: 341-343.

- Vally H, Misso NL, Madan V. Clinical effects of sulphite additives. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1643-1651. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03362.x

- Ralph N, Verma S, Merry S, et al. What is the relevance of contact allergy to sodium metabisulfite and which concentration of the allergen should we use? Dermatitis. 2015;26:162-165. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000120

- Madan V, Walker SL, Beck MH. Sodium metabisulfite allergy is common but is it relevant? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:173-176. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01188.x

- García-Gavín J, Parente J, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by sodium metabisulfite: a challenging allergen. a case series and literature review. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67:260-269. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2012.02135.x

- Milpied B, van Wassenhove L, Larousse C, et al. Contact dermatitis from rifamycin. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14:252-253. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1986.tb01240.x

- Lodi A, Chiarelli G, Mancini LL, et al. Contact allergy to sodium sulfite contained in an antifungal preparation. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:97. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb03493.x

- Sánchez-Pérez J, Abajo P, Córdoba S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from sodium metabisulfite in an antihemorrhoidal cream. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:176-177.

- Boyd AH, Warshaw EM. Sulfites: no longer a zebra? Dermatitis. 2017;28:364-366. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000312

- Grosch E, Mahler V. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by a catheter system containing sodium metabisulfite. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:186-187. doi:10.1111/cod.12675

- Shaver RL, Warshaw EM. Contact allergens in prescription topical ophthalmic medications. Dermatitis. 2022;33:135-143. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000751

- Dendooven E, Darrigade AS, Foubert K, et al. The presence of sulfites in ‘natural rubber latex’ and ‘synthetic’ rubber gloves: an experimental pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1054-1055. doi:10.1111/bjd.18608

- Nater JP. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by potassium metabisulfite. Dermatologica. 1968;136:477-478. doi:10.1159/000254143

- Borges AS, Valejo Coelho MM, Fernandes C, et al. Systemic allergic dermatitis caused by sodium metabisulfite in rectal enemas. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:429-430. doi:10.1111/cod.12971

- Warshaw EM, Buonomo M, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch testing with sodium disulfite: North American Contact Dermatitis Group experience, 2017 to 2018. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:285-296. doi:10.1111/cod.13860

- Häberle M, Geier J, Mahler V. Contact allergy to sulfites: clinical and occupational relevance—new data from the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group and the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:938-941. doi:10.1111/ddg.13009

- Tan MG, Li HO, Pratt MD. Systemic allergic dermatitis to sodium metabisulfite in local anesthetic solution. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86:120-121. doi:10.1111/cod.13978

- D’Amore T, Di Taranto A, Berardi G, et al. Sulfites in meat: occurrence, activity, toxicity, regulation, and detection. a comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19:2701-2720. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12607

- Grotheer P, Marshall M, Simonne A. Sulfites: separating fact from fiction. May 11, 2022. UF IFAS Extension. University of Florida. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FY731

- Silva M, Gama J, Pinto N, et al. Sulfite concentration and the occurrence of headache in young adults: a prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73:1316-1322. doi:10.1038/s41430-019-0420-2

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Reeder MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2019-2020. Dermatitis. 2023;34:90-104. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.29017.jdk

- T.R.U.E. Test. Thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous patch test. SmartPractice Dermatology Allergy. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://www.smartpractice.com/shop/category?id=581719&m=SPA

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost, et al; American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series Committee. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Kaaman AC, Boman A, Wrangsjö K, et al. Contact allergy to sodium metabisulfite: an occupational problem. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:110-112. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01756.x

- Vena GA, Foti C, Angelini G. Sulfite contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:172-175. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01959.x

The American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) selected sulfites as the 2024 Allergen of the Year.1 Due to their preservative and antioxidant properties, sulfites are prevalent in a variety of foods, beverages, medications, and personal care products; however, sulfites also have been implicated as a potential contact allergen. In this article, we review common sources of sulfite exposure, clinical manifestations of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to sulfites, and patch testing considerations for this emerging allergen.

What Are Sulfites?

Sulfiting agents are compounds that contain the sulfite ion SO32-, including sulfur dioxide, sodium disulfite (sodium metabisulfite), and potassium metabisulfite.2 Sulfites occur naturally in the environment and commonly are used as preservatives, antibrowning agents, and antioxidants in various foods, beverages, medications, cosmetics, and skin care products. As antibrowning agents and antioxidants, sulfites help maintain the natural appearance of foods and other products and prevent premature spoiling by inactivating oxidative enzymes.3 It should be noted that sulfites and sulfates are distinct and unrelated compounds that do not cross-react.1

Common Sources of Sulfite Exposure

From a morning glass of juice to an evening shower, in the pharmacy and at the hair salon, sulfite exposure is ubiquitous in most daily routines. Sulfites are present in many foods and beverages, either as a byproduct of natural fermentation or as an additive to prevent spoiling and color change. The Table provides examples of foods with high sulfite content.1,4-6 In particular, dried fruit, bottled lemon juice, wine, grape juice, sauerkraut juice, and pickled onions have high sulfite content.

Topical medications and personal care products represent other potential sources of sulfite exposure. A number of reports have shown that sulfites may be included in topical steroids,7 antibiotics,8 antifungals,9 hemorrhoidal preparations,10 local anesthetics,11 and urinary catheterization gel,12 highlighting their many potential applications. In addition, a comprehensive ingredient analysis of 264 ophthalmic medications found that 3.8% of the products contained sodium disulfite.13 Sulfites may be found in personal care products, including facial and hand cleansers, shampoos, moisturizers, and toothpastes. Hair dyes also commonly contain sulfites,7 which are listed in as many as 90% of hair dye kits in the ACDS Contact Allergen Management Program database.1

Occupational exposures also are widespread, as sulfites are extensively utilized across diverse industries such as pharmaceuticals, health care, leather manufacturing, mineral extraction, food preparation, chemical manufacturing, textiles, alcohol brewing, and wine production.1

Sulfites also are used in the rubber industry—particularly in gloves—due to their anticoagulant and preservative properties.4 This is relevant to health care providers, who may use dozens of disposable gloves in a single day. In an experimental pilot study, researchers detected sulfites in 83% (5/6) of natural rubber latex gloves, 96% (23/24) of synthetic (nitrile) gloves, and 0% (0/5) of polyvinyl chloride gloves.14 While this study was limited to a small sample size, it demonstrates the common use of sulfites in certain rubber gloves and encourages future studies to determine whether there is a quantitative threshold to elicit allergic reactions.

Sulfite Allergy

In 1968, an early case report of ACD to sulfites was published involving a pharmaceutical worker who developed hand eczema after working at a factory for 3 months and had a positive patch test to potassium metabisulfite.15 There have been other cases published in the literature since then, including localized ACD as well as less common cases of systemic contact dermatitis following oral, injectable, and rectal sulfite exposures.16

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group found that, among 132 (2.7%) of 4885 patients with positive patch tests to sodium disulfite from 2017 to 2018, the most commonly involved body sites were the face (28.8%) and hands (20.5%) followed by a scattered/generalized distribution (13.6%). Involvement of the face and hands may correlate with the most frequent sources of exposure that were identified, including personal care products (particularly hair dyes)(18.9%), medications (9.1%), and foods (7.6%).17 A multicenter analysis of patch test results from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland from 1999 to 2013 showed that 357 (2.9%) of 12,156 patients had positive reactions to sodium disulfite, with the most commonly identified exposure sources being topical pharmaceutical agents (59.3%); cosmetics, creams, and sunscreens (13.6%); and systemic drugs (6.8%).18 However, it is not always possible to determine the clinical relevance of a positive patch test to sulfites.1

Other than the face and hands, there have been other unexpected anatomic locations for sulfite ACD (eg, the lower back), and systemic contact dermatitis has manifested with widespread rashes due to oral, rectal, and parenteral exposure.4,16,19 There is no definitive link between sulfite contact allergy and patient sex, but there seems to be a higher prevalence in patients older than 40 years, perhaps related to overall lifetime exposure.1

Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to sulfites also have been reported, including urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis.4 Due to multiple cases of severe dermatologic and respiratory reactions to food products containing sulfites,20 the US Food and Drug Administration prohibited their use in fresh fruit and vegetables as antibrowning agents in 1986 and required labels on packaged foods that contained sulfites at more than 10 parts per million.21 However, food and drinks produced in restaurants, bakeries, and cafes as well as those that are distributed directly to consumers from the preparation site are exempt from these rules.17

In addition, consuming high amounts of dietary sulfites has been linked to headaches through unclear (ie, not necessarily allergic) mechanisms.4,22 One study found that wine with a higher sulfite concentration was associated with increased risk for headaches in participants who had a history of headaches related to wine consumption.22

Patch Testing to Sulfites

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group has tested sodium disulfite since 2017 and found an increased frequency of positive patch tests from 2.7% (N=4885) in 2017 and 201817 to 3.3% (N=4115) in 2019 and 202023 among patients referred for testing. Similarly, patch testing to sodium disulfite in nearly 40,000 patients in 9 European countries showed a pooled prevalence of reactions of 3.1%.17 However, this contact allergy may go unrecognized, as sulfites are not included in common patch test series, including the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous test and the ACDS Core Allergen Series.24,25 The relatively high patch test positivity to sulfites along with the prevalence of daily exposures supports the addition of sulfites to more patch test screening series.

The recommended patch test concentration for sodium disulfite is 1% in petrolatum.5 Testing in aqueous solutions is not recommended because they can cause sulfites to break down, potentially producing false-positive or irritant patch test reactions.7,26,27

Recommendations for Patients With Sulfite Allergies

Individuals with contact allergies to sulfites should be counseled on exposure sources and should be given resources providing a list of safe products, such as the ACDS Contact Allergen Management Program (https://www.acdscamp.org/login) or SkinSAFE (https://www.skinsafeproducts.com/). Prescribers should be cognizant of sulfites that are present in prescription medications. Just because a patient has a positive patch test to sulfites does not automatically imply that they will need to modify their diet to avoid sulfite-containing foods; in the absence of cheilitis or a distribution suggestive of systemic contact dermatitis (eg, vesicular hand/foot dermatitis, intertriginous eruptions), this step may be unnecessary. On the other hand, individuals who have experienced immediate hypersensitivity reactions to sulfites should avoid sulfite-containing foods and carry an epinephrine autoinjector.

Final Interpretation

Sulfites are ubiquitous compounds found in various foods, beverages, medications, and personal care products in addition to a range of occupational exposures. The face and hands are the most common sites of sulfite ACD. Despite patch test positivity in as many as 3% of tested patients,17,23 sulfite allergy may be missed due to lack of routine testing on standard screening series.

The American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) selected sulfites as the 2024 Allergen of the Year.1 Due to their preservative and antioxidant properties, sulfites are prevalent in a variety of foods, beverages, medications, and personal care products; however, sulfites also have been implicated as a potential contact allergen. In this article, we review common sources of sulfite exposure, clinical manifestations of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to sulfites, and patch testing considerations for this emerging allergen.

What Are Sulfites?

Sulfiting agents are compounds that contain the sulfite ion SO32-, including sulfur dioxide, sodium disulfite (sodium metabisulfite), and potassium metabisulfite.2 Sulfites occur naturally in the environment and commonly are used as preservatives, antibrowning agents, and antioxidants in various foods, beverages, medications, cosmetics, and skin care products. As antibrowning agents and antioxidants, sulfites help maintain the natural appearance of foods and other products and prevent premature spoiling by inactivating oxidative enzymes.3 It should be noted that sulfites and sulfates are distinct and unrelated compounds that do not cross-react.1

Common Sources of Sulfite Exposure

From a morning glass of juice to an evening shower, in the pharmacy and at the hair salon, sulfite exposure is ubiquitous in most daily routines. Sulfites are present in many foods and beverages, either as a byproduct of natural fermentation or as an additive to prevent spoiling and color change. The Table provides examples of foods with high sulfite content.1,4-6 In particular, dried fruit, bottled lemon juice, wine, grape juice, sauerkraut juice, and pickled onions have high sulfite content.

Topical medications and personal care products represent other potential sources of sulfite exposure. A number of reports have shown that sulfites may be included in topical steroids,7 antibiotics,8 antifungals,9 hemorrhoidal preparations,10 local anesthetics,11 and urinary catheterization gel,12 highlighting their many potential applications. In addition, a comprehensive ingredient analysis of 264 ophthalmic medications found that 3.8% of the products contained sodium disulfite.13 Sulfites may be found in personal care products, including facial and hand cleansers, shampoos, moisturizers, and toothpastes. Hair dyes also commonly contain sulfites,7 which are listed in as many as 90% of hair dye kits in the ACDS Contact Allergen Management Program database.1

Occupational exposures also are widespread, as sulfites are extensively utilized across diverse industries such as pharmaceuticals, health care, leather manufacturing, mineral extraction, food preparation, chemical manufacturing, textiles, alcohol brewing, and wine production.1

Sulfites also are used in the rubber industry—particularly in gloves—due to their anticoagulant and preservative properties.4 This is relevant to health care providers, who may use dozens of disposable gloves in a single day. In an experimental pilot study, researchers detected sulfites in 83% (5/6) of natural rubber latex gloves, 96% (23/24) of synthetic (nitrile) gloves, and 0% (0/5) of polyvinyl chloride gloves.14 While this study was limited to a small sample size, it demonstrates the common use of sulfites in certain rubber gloves and encourages future studies to determine whether there is a quantitative threshold to elicit allergic reactions.

Sulfite Allergy

In 1968, an early case report of ACD to sulfites was published involving a pharmaceutical worker who developed hand eczema after working at a factory for 3 months and had a positive patch test to potassium metabisulfite.15 There have been other cases published in the literature since then, including localized ACD as well as less common cases of systemic contact dermatitis following oral, injectable, and rectal sulfite exposures.16

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group found that, among 132 (2.7%) of 4885 patients with positive patch tests to sodium disulfite from 2017 to 2018, the most commonly involved body sites were the face (28.8%) and hands (20.5%) followed by a scattered/generalized distribution (13.6%). Involvement of the face and hands may correlate with the most frequent sources of exposure that were identified, including personal care products (particularly hair dyes)(18.9%), medications (9.1%), and foods (7.6%).17 A multicenter analysis of patch test results from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland from 1999 to 2013 showed that 357 (2.9%) of 12,156 patients had positive reactions to sodium disulfite, with the most commonly identified exposure sources being topical pharmaceutical agents (59.3%); cosmetics, creams, and sunscreens (13.6%); and systemic drugs (6.8%).18 However, it is not always possible to determine the clinical relevance of a positive patch test to sulfites.1

Other than the face and hands, there have been other unexpected anatomic locations for sulfite ACD (eg, the lower back), and systemic contact dermatitis has manifested with widespread rashes due to oral, rectal, and parenteral exposure.4,16,19 There is no definitive link between sulfite contact allergy and patient sex, but there seems to be a higher prevalence in patients older than 40 years, perhaps related to overall lifetime exposure.1

Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to sulfites also have been reported, including urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis.4 Due to multiple cases of severe dermatologic and respiratory reactions to food products containing sulfites,20 the US Food and Drug Administration prohibited their use in fresh fruit and vegetables as antibrowning agents in 1986 and required labels on packaged foods that contained sulfites at more than 10 parts per million.21 However, food and drinks produced in restaurants, bakeries, and cafes as well as those that are distributed directly to consumers from the preparation site are exempt from these rules.17

In addition, consuming high amounts of dietary sulfites has been linked to headaches through unclear (ie, not necessarily allergic) mechanisms.4,22 One study found that wine with a higher sulfite concentration was associated with increased risk for headaches in participants who had a history of headaches related to wine consumption.22

Patch Testing to Sulfites

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group has tested sodium disulfite since 2017 and found an increased frequency of positive patch tests from 2.7% (N=4885) in 2017 and 201817 to 3.3% (N=4115) in 2019 and 202023 among patients referred for testing. Similarly, patch testing to sodium disulfite in nearly 40,000 patients in 9 European countries showed a pooled prevalence of reactions of 3.1%.17 However, this contact allergy may go unrecognized, as sulfites are not included in common patch test series, including the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous test and the ACDS Core Allergen Series.24,25 The relatively high patch test positivity to sulfites along with the prevalence of daily exposures supports the addition of sulfites to more patch test screening series.

The recommended patch test concentration for sodium disulfite is 1% in petrolatum.5 Testing in aqueous solutions is not recommended because they can cause sulfites to break down, potentially producing false-positive or irritant patch test reactions.7,26,27

Recommendations for Patients With Sulfite Allergies

Individuals with contact allergies to sulfites should be counseled on exposure sources and should be given resources providing a list of safe products, such as the ACDS Contact Allergen Management Program (https://www.acdscamp.org/login) or SkinSAFE (https://www.skinsafeproducts.com/). Prescribers should be cognizant of sulfites that are present in prescription medications. Just because a patient has a positive patch test to sulfites does not automatically imply that they will need to modify their diet to avoid sulfite-containing foods; in the absence of cheilitis or a distribution suggestive of systemic contact dermatitis (eg, vesicular hand/foot dermatitis, intertriginous eruptions), this step may be unnecessary. On the other hand, individuals who have experienced immediate hypersensitivity reactions to sulfites should avoid sulfite-containing foods and carry an epinephrine autoinjector.

Final Interpretation

Sulfites are ubiquitous compounds found in various foods, beverages, medications, and personal care products in addition to a range of occupational exposures. The face and hands are the most common sites of sulfite ACD. Despite patch test positivity in as many as 3% of tested patients,17,23 sulfite allergy may be missed due to lack of routine testing on standard screening series.

- Ekstein SF, Warshaw EM. Sulfites: allergen of the year 2024. Dermatitis. 2024;35:6-12. doi:10.1089/derm.2023.0154

- Gunnison AF, Jacobsen DW. Sulfite hypersensitivity. a critical review. CRC Crit Rev Toxicol. 1987;17:185-214. doi:10.3109/10408448709071208

- Clough SR. Sodium sulfite. In: Wexler P, ed. Encyclopedia of Toxicology. 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2014: 341-343.

- Vally H, Misso NL, Madan V. Clinical effects of sulphite additives. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1643-1651. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03362.x

- Ralph N, Verma S, Merry S, et al. What is the relevance of contact allergy to sodium metabisulfite and which concentration of the allergen should we use? Dermatitis. 2015;26:162-165. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000120

- Madan V, Walker SL, Beck MH. Sodium metabisulfite allergy is common but is it relevant? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:173-176. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01188.x

- García-Gavín J, Parente J, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by sodium metabisulfite: a challenging allergen. a case series and literature review. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67:260-269. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2012.02135.x

- Milpied B, van Wassenhove L, Larousse C, et al. Contact dermatitis from rifamycin. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14:252-253. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1986.tb01240.x

- Lodi A, Chiarelli G, Mancini LL, et al. Contact allergy to sodium sulfite contained in an antifungal preparation. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:97. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb03493.x

- Sánchez-Pérez J, Abajo P, Córdoba S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from sodium metabisulfite in an antihemorrhoidal cream. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:176-177.

- Boyd AH, Warshaw EM. Sulfites: no longer a zebra? Dermatitis. 2017;28:364-366. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000312

- Grosch E, Mahler V. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by a catheter system containing sodium metabisulfite. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:186-187. doi:10.1111/cod.12675

- Shaver RL, Warshaw EM. Contact allergens in prescription topical ophthalmic medications. Dermatitis. 2022;33:135-143. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000751

- Dendooven E, Darrigade AS, Foubert K, et al. The presence of sulfites in ‘natural rubber latex’ and ‘synthetic’ rubber gloves: an experimental pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1054-1055. doi:10.1111/bjd.18608

- Nater JP. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by potassium metabisulfite. Dermatologica. 1968;136:477-478. doi:10.1159/000254143

- Borges AS, Valejo Coelho MM, Fernandes C, et al. Systemic allergic dermatitis caused by sodium metabisulfite in rectal enemas. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:429-430. doi:10.1111/cod.12971

- Warshaw EM, Buonomo M, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch testing with sodium disulfite: North American Contact Dermatitis Group experience, 2017 to 2018. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:285-296. doi:10.1111/cod.13860

- Häberle M, Geier J, Mahler V. Contact allergy to sulfites: clinical and occupational relevance—new data from the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group and the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:938-941. doi:10.1111/ddg.13009

- Tan MG, Li HO, Pratt MD. Systemic allergic dermatitis to sodium metabisulfite in local anesthetic solution. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86:120-121. doi:10.1111/cod.13978

- D’Amore T, Di Taranto A, Berardi G, et al. Sulfites in meat: occurrence, activity, toxicity, regulation, and detection. a comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19:2701-2720. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12607

- Grotheer P, Marshall M, Simonne A. Sulfites: separating fact from fiction. May 11, 2022. UF IFAS Extension. University of Florida. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FY731

- Silva M, Gama J, Pinto N, et al. Sulfite concentration and the occurrence of headache in young adults: a prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73:1316-1322. doi:10.1038/s41430-019-0420-2

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Reeder MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2019-2020. Dermatitis. 2023;34:90-104. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.29017.jdk

- T.R.U.E. Test. Thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous patch test. SmartPractice Dermatology Allergy. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://www.smartpractice.com/shop/category?id=581719&m=SPA

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost, et al; American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series Committee. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Kaaman AC, Boman A, Wrangsjö K, et al. Contact allergy to sodium metabisulfite: an occupational problem. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:110-112. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01756.x

- Vena GA, Foti C, Angelini G. Sulfite contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:172-175. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01959.x

- Ekstein SF, Warshaw EM. Sulfites: allergen of the year 2024. Dermatitis. 2024;35:6-12. doi:10.1089/derm.2023.0154

- Gunnison AF, Jacobsen DW. Sulfite hypersensitivity. a critical review. CRC Crit Rev Toxicol. 1987;17:185-214. doi:10.3109/10408448709071208

- Clough SR. Sodium sulfite. In: Wexler P, ed. Encyclopedia of Toxicology. 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2014: 341-343.

- Vally H, Misso NL, Madan V. Clinical effects of sulphite additives. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1643-1651. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03362.x

- Ralph N, Verma S, Merry S, et al. What is the relevance of contact allergy to sodium metabisulfite and which concentration of the allergen should we use? Dermatitis. 2015;26:162-165. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000120

- Madan V, Walker SL, Beck MH. Sodium metabisulfite allergy is common but is it relevant? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:173-176. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01188.x

- García-Gavín J, Parente J, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by sodium metabisulfite: a challenging allergen. a case series and literature review. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67:260-269. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2012.02135.x

- Milpied B, van Wassenhove L, Larousse C, et al. Contact dermatitis from rifamycin. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14:252-253. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1986.tb01240.x

- Lodi A, Chiarelli G, Mancini LL, et al. Contact allergy to sodium sulfite contained in an antifungal preparation. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:97. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb03493.x

- Sánchez-Pérez J, Abajo P, Córdoba S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from sodium metabisulfite in an antihemorrhoidal cream. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:176-177.

- Boyd AH, Warshaw EM. Sulfites: no longer a zebra? Dermatitis. 2017;28:364-366. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000312

- Grosch E, Mahler V. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by a catheter system containing sodium metabisulfite. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:186-187. doi:10.1111/cod.12675

- Shaver RL, Warshaw EM. Contact allergens in prescription topical ophthalmic medications. Dermatitis. 2022;33:135-143. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000751

- Dendooven E, Darrigade AS, Foubert K, et al. The presence of sulfites in ‘natural rubber latex’ and ‘synthetic’ rubber gloves: an experimental pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1054-1055. doi:10.1111/bjd.18608

- Nater JP. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by potassium metabisulfite. Dermatologica. 1968;136:477-478. doi:10.1159/000254143

- Borges AS, Valejo Coelho MM, Fernandes C, et al. Systemic allergic dermatitis caused by sodium metabisulfite in rectal enemas. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:429-430. doi:10.1111/cod.12971

- Warshaw EM, Buonomo M, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch testing with sodium disulfite: North American Contact Dermatitis Group experience, 2017 to 2018. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:285-296. doi:10.1111/cod.13860

- Häberle M, Geier J, Mahler V. Contact allergy to sulfites: clinical and occupational relevance—new data from the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group and the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:938-941. doi:10.1111/ddg.13009

- Tan MG, Li HO, Pratt MD. Systemic allergic dermatitis to sodium metabisulfite in local anesthetic solution. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86:120-121. doi:10.1111/cod.13978

- D’Amore T, Di Taranto A, Berardi G, et al. Sulfites in meat: occurrence, activity, toxicity, regulation, and detection. a comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19:2701-2720. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12607

- Grotheer P, Marshall M, Simonne A. Sulfites: separating fact from fiction. May 11, 2022. UF IFAS Extension. University of Florida. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FY731

- Silva M, Gama J, Pinto N, et al. Sulfite concentration and the occurrence of headache in young adults: a prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73:1316-1322. doi:10.1038/s41430-019-0420-2

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Reeder MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2019-2020. Dermatitis. 2023;34:90-104. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.29017.jdk

- T.R.U.E. Test. Thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous patch test. SmartPractice Dermatology Allergy. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://www.smartpractice.com/shop/category?id=581719&m=SPA

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost, et al; American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series Committee. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Kaaman AC, Boman A, Wrangsjö K, et al. Contact allergy to sodium metabisulfite: an occupational problem. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:110-112. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01756.x

- Vena GA, Foti C, Angelini G. Sulfite contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:172-175. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01959.x

Practice Points

- Sulfites are ubiquitous compounds that serve as preservatives and antioxidants in various foods, beverages, medications, and personal care products.

- Allergic contact dermatitis to sulfites most commonly affects the face and hands.

- Because sulfites are not included in most patch test screening series, contact allergy to sulfites may be missed unless expanded testing is performed.